A Comprehensive Guide to 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing for Microbiome Analysis: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive protocol and critical analysis of 16S rRNA gene sequencing for microbiome analysis, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

A Comprehensive Guide to 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing for Microbiome Analysis: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications in Biomedical Research

Abstract

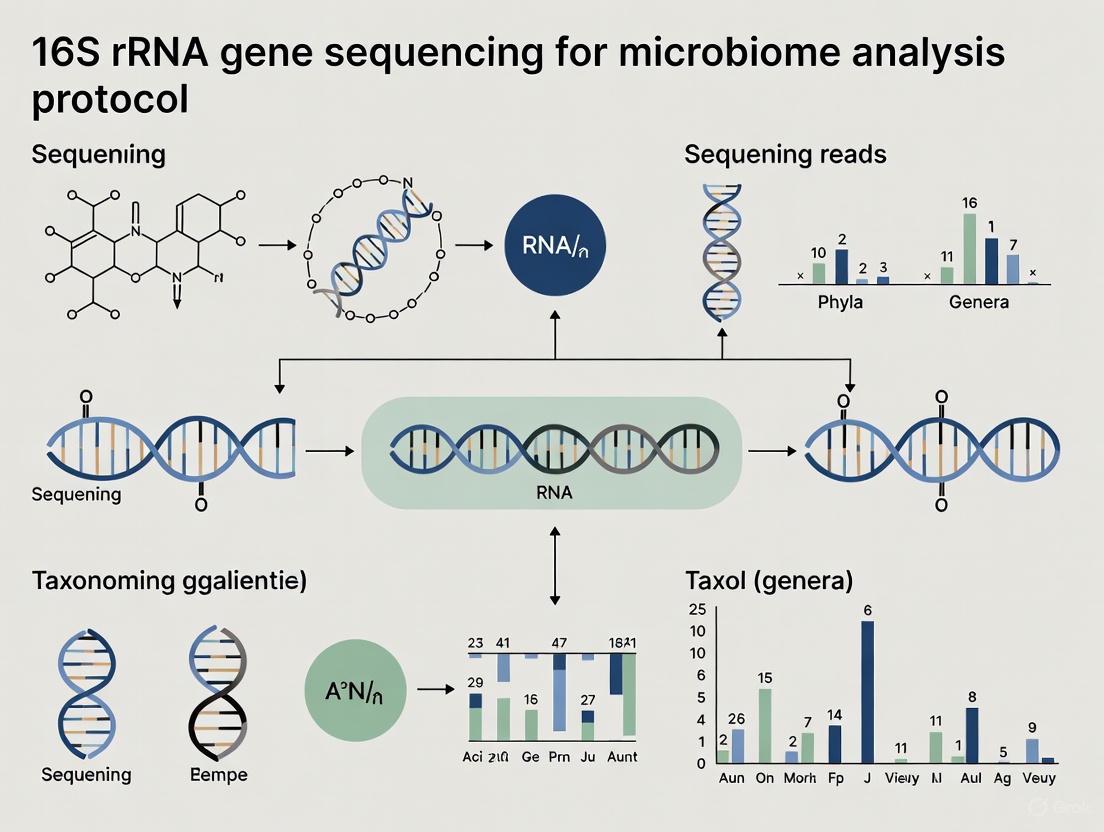

This article provides a comprehensive protocol and critical analysis of 16S rRNA gene sequencing for microbiome analysis, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, detailing the structure and evolutionary significance of the 16S rRNA gene as a phylogenetic marker. A step-by-step methodological workflow is presented, from sample collection and DNA extraction through library preparation, sequencing, and bioinformatics analysis. The guide addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, including primer selection, contamination control, and data interpretation pitfalls. Finally, it offers a rigorous validation and comparative framework, evaluating the technique's resolution against shotgun metagenomics and its growing role in clinical and translational research, such as understanding the gut microbiome in colorectal cancer and other disease states.

The 16S rRNA Gene: Unlocking Bacterial Phylogeny and Taxonomy

What is the 16S rRNA Gene? Structure, Function, and Conservation

The 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene is a fundamental genetic component found in all prokaryotes (bacteria and archaea) and serves as the cornerstone of microbial phylogenetics and taxonomy [1] [2]. As the DNA sequence that codes for the RNA component of the 30S small ribosomal subunit, its primary role is in the essential cellular process of protein synthesis [1] [3]. The gene's significance, however, extends far beyond this basic function. Its highly conserved nature, interspersed with species-specific variable regions, has established it as the most widely used molecular marker for bacterial identification and phylogenetic reconstruction [2] [4]. The pioneering work of Carl Woese in the 1970s, which utilized 16S rRNA gene sequencing to delineate the domain of Archaea, solidified its status as an indispensable "molecular clock" for evolutionary studies [1] [2] [5]. This application note details the structure, function, and conserved properties of the 16S rRNA gene, providing researchers with the foundational knowledge and protocols required for its application in modern microbiome analysis.

Structural Organization of the 16S rRNA Gene

The 16S rRNA gene has a length of approximately 1,500 to 1,550 base pairs and exhibits a characteristic architecture of conserved and variable regions that is critical to its utility [2] [3]. The "S" in 16S stands for Svedberg unit, which reflects the sedimentation coefficient of the ribosomal subunit and indirectly indicates its molecular size [1].

Conserved and Hypervariable Regions

The gene comprises nine hypervariable regions (V1-V9), which are short sequences (typically 30-100 base pairs long) flanked by longer, highly conserved regions [1] [4]. The variable regions accumulate mutations at a higher rate and provide the species-specific signature sequences necessary for discrimination, whereas the conserved regions are vital for the ribosome's core function and enable the design of universal PCR primers [1] [3].

Table 1: Characteristics of the Hypervariable Regions in the 16S rRNA Gene

| Region | Approximate Length (bp) | Key Characteristics and Applications |

|---|---|---|

| V1-V2 | ~510 bp | Provides good results for Escherichia/Shigella; can be sequenced on Roche 454 platform [1] [6]. |

| V3-V4 | ~428 bp | Commonly targeted by Illumina MiSeq; good for broad community analysis [1] [3]. |

| V4 | ~252 bp | A semi-conserved region; provides accurate phylum-level resolution and is commonly used in Illumina HiSeq [1] [6] [3]. |

| V6-V9 | ~548 bp | Noted as the best sub-region for classifying Clostridium and Staphylococcus [1] [6]. |

| V1-V9 | ~1500 bp | The full-length gene; provides the highest taxonomic accuracy across all taxa [6] [7]. |

Secondary and Tertiary Structure

The 16S rRNA molecule folds into a complex secondary and tertiary structure defined by base-pairing interactions, forming numerous stem-loops (helices) [1] [3]. This intricate structure acts as a scaffold, defining the positions of ribosomal proteins and facilitating its functional interactions within the ribosome [1] [5].

Biological Function and Conservation

Core Functions in Protein Synthesis

The 16S rRNA is not merely a structural component; it is functionally catalytic and critical for the initiation and fidelity of protein synthesis [1]. Its key functions include:

- mRNA Binding and Initiation: The 3′-end of the 16S rRNA contains the anti-Shine-Dalgarno sequence, which binds complementarily to the Shine-Dalgarno sequence on mRNA, ensuring correct positioning of the start codon (AUG) in the ribosomal P-site [1] [3].

- Ribosomal Subunit Interaction: The 16S rRNA directly interacts with the 23S rRNA of the large ribosomal subunit (50S), facilitating the stable binding of the 30S and 50S subunits to form the functional 70S ribosome [1] [3].

- Codon-Anticodon Stabilization: Within the ribosomal A-site, specific adenine residues (1492 and 1493) in the 16S rRNA form hydrogen bonds with the mRNA backbone, thereby stabilizing the correct codon-anticodon pairing between mRNA and tRNA and ensuring translational accuracy [1].

Evolutionary Conservation and Variation

The 16S rRNA gene is described as a "molecular fossil" due to its essential and unchanging role in the cell, which imposes strong evolutionary constraints, resulting in slow rates of sequence change [1] [3]. This makes it an excellent chronometer for measuring deep evolutionary relationships [2]. However, several factors complicate its use:

- Intragenomic Heterogeneity: Many bacterial genomes contain multiple copies of the 16S rRNA gene (operons), and sequence variation can exist between these copies within a single organism [1] [6] [8]. This heterogeneity can confound precise species-level identification and must be accounted for in high-resolution analyses [6].

- Horizontal Gene Transfer (HGT): Evidence shows that the 16S rRNA gene can be transferred horizontally between distantly related bacteria, challenging the assumption of strict vertical inheritance [1] [5] [8]. This promiscuity can lead to discordance between the 16S rRNA gene phylogeny and the true species phylogeny [8].

- Functional Conservation: Remarkably, despite significant sequence divergence, 16S rRNA genes from different phyla can be functionally interchangeable. Experimental evidence has demonstrated that an acidobacterial 16S rRNA gene (sharing only 78% identity with E. coli) could functionally complement E. coli ribosomes after a single base-pair correction, indicating that the molecular function is highly conserved even as the sequence evolves [5].

Experimental Protocols and Reagents

The following section outlines a detailed protocol for full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing using Oxford Nanopore Technology (ONT), optimized from recent studies [7].

Full-Length 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing via MinION

Principle: This protocol leverages long-read nanopore sequencing to generate full-length (~1,500 bp) 16S rRNA amplicons, which provides superior taxonomic resolution compared to short-read sequencing of individual hypervariable regions [6] [7].

Workflow:

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Extract high-quality genomic DNA from the microbial sample (e.g., using a ZymoBIOMICS DNA Miniprep Kit). Validate DNA purity and concentration using spectrophotometry and fluorometry, respectively.

- Full-Length 16S Amplification:

- Primers: Use universal primer pair 27F (5'-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3') and 1492R (5'-CGGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3') to target the V1-V9 regions [1] [7].

- PCR Reaction:

- Template DNA: 1 ng

- Primers: 400 nM each

- Polymerase: 12.5 µL LongAmp Hot Start Taq DNA Polymerase (recommended for long amplicons)

- Total reaction volume: 25 µL

- Thermocycling Conditions:

- Initial Denaturation: 94°C for 1 min (1 cycle)

- Amplification: Denature at 94°C for 20 s, Anneal at 50°C for 30 s, Extend at 65°C for 90 s (25 cycles)

- Final Extension: 65°C for 3 min (1 cycle)

- Note: Limiting PCR cycles to 25 is critical to minimize amplification bias [7].

- PCR Product Purification: Purify the amplified ~1,500 bp product using SPRIselect magnetic beads according to the manufacturer's instructions. Quantify the purified DNA using a Qubit dsDNA BR Assay Kit.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Following the ONT "PCR barcoding amplicons" protocol (SQK-LSK109), barcode the purified amplicons from multiple samples using a PCR Barcoding Expansion kit. Pool the barcoded libraries, load them onto a MinION R9.4.1 flow cell, and perform sequencing for up to 48 hours.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

| Item | Function/Application | Example Product/Catalog Number |

|---|---|---|

| Universal Primers (27F/1492R) | PCR amplification of the full-length 16S rRNA gene (V1-V9). | Custom synthesized oligos [7]. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Accurate amplification of long (~1.5 kb) amplicons with low error rate. | LongAmp Hot Start Taq DNA Polymerase (NEB M0534) [7]. |

| Magnetic Beads | Size-selective purification and cleanup of PCR amplicons. | SPRIselect magnetic beads (Beckman Coulter B23317) [7]. |

| DNA Quantitation Kit | Accurate quantification of low-concentration DNA for library preparation. | Qubit dsDNA BR Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific Q33238) [7]. |

| Barcoding Kit | Multiplexing samples by adding unique molecular barcodes during library prep. | ONT PCR Barcoding Expansion 1–96 (EXP-PBC096) [7]. |

| Sequencing Platform | Long-read sequencing of full-length 16S amplicons. | Oxford Nanopore MinION with R9.4.1 flow cell [7]. |

| Reference Database | Taxonomic classification of sequenced reads. | SILVA, Greengenes [1]. |

Applications in Microbial Research

The 16S rRNA gene is indispensable in modern microbiology and has enabled a paradigm shift from culture-based to sequence-based identification and community analysis.

- Microbiome Profiling: 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing is the primary method for characterizing complex bacterial communities in environments like the human gut, oral cavity, and soil [4] [9]. It allows researchers to determine which taxa are present and their relative abundances, linking dysbiosis to health and disease states [4].

- Clinical Microbiology and Pathogen Identification: The gene is routinely used in clinical labs to identify poorly described, rarely isolated, or phenotypically aberrant strains, leading to the recognition of novel pathogens [2]. It has demonstrated enhanced detection sensitivity compared to traditional culture, even after antibiotic treatment [1].

- Forensic Science: The highly individualized nature of human microbiomes, particularly on skin and in saliva, allows 16S rRNA profiling to be used for individual identification and linking persons to objects or locations [9].

- Phylogenetics and Species Delineation: Despite limitations at the strain level, the 16S rRNA gene remains the standard for determining the phylogenetic placement of new bacterial isolates and for delineating species, often with a 97% sequence similarity threshold used as a rule-of-thumb for species boundaries [6] [2].

Limitations and Considerations

While powerful, 16S rRNA gene analysis has inherent limitations that researchers must consider during experimental design and data interpretation.

- Limited Taxonomic Resolution: The gene often lacks the resolution to distinguish between closely related species or strains, particularly in taxa like Enterobacteriaceae and Clostridiaceae, which can share >99% 16S sequence similarity [1] [6].

- PCR and Bioinformatics Biases: The choice of primers, number of PCR cycles, polymerase, and bioinformatics pipeline (e.g., BugSeq vs. EPI2ME) can all significantly influence the resulting microbial community composition and must be carefully optimized and reported [7].

- Variable Copy Number: The number of 16S rRNA gene operons in a genome can range from 1 to 27, which can skew abundance estimates in community analyses, as taxa with higher copy numbers may be overrepresented [8].

- Phylogenetic Discordance: Phylogenies based on the 16S rRNA gene, especially its hypervariable regions, can show poor concordance with phylogenies based on the core genome due to recombination, HGT, and intragenomic variation [8]. Therefore, for strain-level analysis or robust phylogenetic inference, whole-genome sequencing is recommended.

The 16S rRNA gene is a uniquely powerful tool in microbial biology due to its universal distribution, functional constancy, and mosaic of conserved and variable sequences. Its structure is perfectly suited for its dual role in essential ribosomal function and as a molecular marker for identification and classification. While next-generation sequencing technologies now enable routine full-length 16S sequencing, offering superior resolution over short-read approaches, researchers must remain cognizant of its limitations, including copy number variation, limited strain-level discrimination, and phylogenetic discordance. A thorough understanding of the gene's structure, function, and conservation—as outlined in this application note—is fundamental to designing robust experiments, selecting appropriate protocols, and accurately interpreting data across diverse fields from clinical diagnostics to ecosystem ecology.

Why a Single Gene? The Principle Behind Using 16S as a Molecular Clock

The 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene has served as a cornerstone of microbial phylogenetics and taxonomy for decades. Its application as a molecular chronometer enables researchers to determine evolutionary relationships among bacteria and archaea, providing a framework for understanding microbial diversity in complex environments. This application note details the fundamental principles that establish the 16S rRNA gene as a preferred genetic marker, its specific structural properties that facilitate phylogenetic analysis, and standardized protocols for its application in modern microbiome research. By integrating theoretical foundations with practical methodologies, this document serves as an essential resource for researchers and drug development professionals employing 16S rRNA gene sequencing in their investigative workflows.

The Scientific Rationale for the 16S rRNA Gene

The selection of the 16S rRNA gene for phylogenetic studies is not arbitrary; it is grounded in a unique combination of molecular properties that make it exceptionally suitable as a molecular clock. As noted in early pioneering work, the gene functions as a molecular chronometer, where the degree of sequence conservation reflects its critical role in cell function [2]. The 16S rRNA is a component of the 30S subunit of the bacterial ribosome, which is indispensable for protein synthesis. This fundamental physiological role imposes strong selective pressure against mutations, particularly in regions directly involved in ribosomal assembly and function.

Several key attributes solidify its status as the gold standard marker:

- Universal Distribution: The gene is present in all bacteria and archaea, allowing for broad phylogenetic comparisons across all prokaryotic life [2] [10].

- Optimal Size and Structure: At approximately 1,550 base pairs in length, it provides a sufficiently large sequence for meaningful statistical analysis [2] [6]. Its structure comprises nine variable regions (V1-V9) interspersed with conserved regions. The variable regions provide the phylogenetic signal for distinguishing between taxa, while the conserved regions enable the design of universal PCR primers [2] [10] [11].

- Slow Evolutionary Rate: The gene exhibits a slow, relatively constant rate of sequence evolution over time. While not perfectly constant, this rate is sufficient to mark evolutionary distance and relatedness among organisms, fulfilling a primary requirement for a molecular clock [2].

- Extensive Reference Databases: Large, curated databases such as SILVA, Greengenes, and the RDP (Ribosome Database Project) contain hundreds of thousands of 16S rRNA sequences, providing an indispensable framework for taxonomic classification of newly sequenced data [2] [11].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of the 16S rRNA Gene as a Molecular Marker

| Characteristic | Description | Functional Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Universal Presence | Found in all bacteria and archaea. | Enables comprehensive profiling of entire prokaryotic communities. |

| Gene Length | ~1,500 base pairs. | Provides a sufficient amount of sequence data for robust statistical analysis. |

| Functional Constancy | Encodes a critical component of the protein synthesis machinery. | Subject to strong selective pressure, ensuring evolutionary relevance. |

| Structural Architecture | Combination of 9 variable and conserved regions. | Variable regions enable discrimination; conserved regions enable amplification. |

| Evolutionary Rate | Slow and relatively constant accumulation of mutations. | Acts as a "molecular clock" for measuring evolutionary time and relatedness. |

Structural Architecture and Phylogenetic Signal

The discriminatory power of the 16S rRNA gene stems from its chimeric architecture of variable and conserved regions. The conserved sequences reflect the common ancestry and essential function of the ribosome, while the hypervariable regions accumulate mutations at a higher rate, serving as unique fingerprints for different taxonomic groups.

The following diagram illustrates the structure of the 16S rRNA gene and the workflow for leveraging it in phylogenetic analysis:

This combination of stability and variability allows the 16S gene to be used for phylogenetic assignments at multiple levels. The conserved regions allow for the alignment of sequences from vastly different organisms and the design of broad-range PCR primers. The variable regions provide the necessary sequence divergence to distinguish between organisms at different taxonomic depths, from the phylum level down to the species and, in some cases, the strain level [2] [6]. It is crucial to note that the variable regions evolve at different rates, and no single region can resolve all bacterial taxa equally well. The choice of which variable region(s) to sequence is therefore a critical methodological consideration that depends on the specific research question and the bacterial lineages of interest [6] [12].

Wet-Lab Protocol: 16S rRNA Gene Amplicon Sequencing

This section provides a standardized protocol for generating 16S rRNA gene sequence data from complex microbial communities, such as those found in gut, skin, or environmental samples.

Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

Objective: To obtain high-quality microbial genomic DNA suitable for PCR amplification. Critical Considerations:

- Sample Preservation: Immediately freeze samples at -80°C or use commercial preservation buffers to prevent microbial community shifts.

- Low-Biomass Protocols: For samples with low bacterial density (e.g., skin, water), use extraction kits specifically validated for low biomass to minimize host DNA contamination and maximize microbial DNA yield [13]. Protocols involving D-Squame discs followed by in-house DNA extraction have been shown to be effective for skin [13].

- Inhibitor Removal: Ensure the extraction protocol effectively removes PCR inhibitors (e.g., humic acids in soil, bile salts in gut samples).

PCR Amplification of Target Regions

Objective: To specifically amplify the 16S rRNA gene or its hypervariable regions.

Reaction Setup:

| Component | Volume (μL) | Final Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| PCR-Grade Water | 10.5 | - |

| 2X KOD One PCR Master Mix | 15.0 | 1X |

| Mixed Forward/Reverse Primers (10 μM each) | 3.0 | 0.3 μM each |

| Template DNA (10-20 ng/μL) | 1.5 | 1-3 ng/μL |

| Total Volume | 30.0 |

Primer Selection: The choice of primers determines the variable region sequenced. Common choices include:

- 27F (AGRGTTTGATYNTGGCTCAG) and 1492R (TASGGHTACCTTGTTASGACTT) for full-length 16S [12].

- Region-specific primers (e.g., targeting V3-V4 for Illumina short-read sequencing).

Thermocycling Conditions:

| Cycle Step | Temperature | Time | Cycles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Denaturation | 95°C | 2 minutes | 1 |

| Denaturation | 98°C | 10 seconds | 25 |

| Annealing | 55°C | 30 seconds | 25 |

| Extension | 72°C | 90 seconds | 25 |

| Final Extension | 72°C | 2 minutes | 1 |

| Hold | 4°C | ∞ | 1 |

Library Preparation and Sequencing

Objective: To prepare the PCR amplicons for next-generation sequencing. Steps:

- Purification: Clean PCR products using magnetic beads (e.g., AMPure XP/PB beads) to remove primers, dimers, and salts.

- Library Construction: For Illumina platforms, add sequencing adapters and dual-index barcodes via a second, limited-cycle PCR. This allows multiplexing of samples.

- Quality Control: Assess library concentration (e.g., via Qubit fluorometry) and fragment size (e.g., via Agilent Bioanalyzer).

- Sequencing: Pool libraries at equimolar concentrations and sequence on an appropriate platform (e.g., Illumina MiSeq for 2x300 bp V3-V4 reads; PacBio Sequel II for full-length 16S).

Bioinformatic Analysis: From Raw Sequences to Taxonomy

The transformation of raw sequencing data into biological insights requires a multi-step bioinformatic pipeline, implemented using various software packages and reference databases.

Core Bioinformatics Workflow

The following diagram outlines the standard bioinformatic processing steps for 16S rRNA amplicon data:

Key Steps and Tools

- Quality Filtering: Remove low-quality reads, trim adapter sequences, and truncate reads based on quality scores.

- Denoising and Chimera Removal: Correct sequencing errors and remove chimeric PCR artifacts using algorithms like those in DADA2 or QIIME 2 to resolve true biological sequences down to single-nucleotide differences [14] [6].

- Sequence Variant Inference: Generate Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) or cluster sequences into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs). ASVs provide a higher resolution and are now generally preferred over OTUs.

- Taxonomic Assignment: Classify ASVs/OTUs by comparing them against curated reference databases using classifiers like the RDP classifier or BLAST [2] [11].

Table 2: Key Reagents and Computational Tools for 16S rRNA Analysis

| Category | Item | Specification/Version | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents | PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit | - | DNA extraction from complex samples. |

| KOD One PCR Master Mix | - | High-fidelity amplification of 16S gene. | |

| AMPure PB Beads | - | Purification and size-selection of PCR amplicons. | |

| Primer Sets | 27F / 1492R | - | Amplification of the full-length 16S rRNA gene. |

| 341F / 806R | - | Amplification of the V3-V4 hypervariable region. | |

| Bioinformatic Tools | QIIME 2 | 2024.5 | End-to-end microbiome analysis platform. |

| DADA2 | 1.28 | Inference of exact ASVs from amplicon data. | |

| phyloseq (R) | 1.44 | Statistical analysis and visualization of microbiome data. | |

| SILVA Database | SSU 138 | Curated database for taxonomic classification. |

Technical Considerations and Emerging Best Practices

Full-Length vs. Partial Gene Sequencing

The advent of third-generation sequencing (PacBio and Oxford Nanopore) has made high-throughput sequencing of the full-length (~1500 bp) 16S rRNA gene a reality. Evidence strongly supports the superiority of full-length sequencing for taxonomic resolution.

Table 3: Comparison of Sequencing Approaches for the 16S rRNA Gene

| Parameter | Short-Read (e.g., V4 Region) | Long-Read (Full-Length V1-V9) |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Platform | Illumina MiSeq/NovaSeq | PacBio Sequel IIe, Oxford Nanopore |

| Taxonomic Resolution | Good for genus-level, poor for species-level. | Superior; enables species and strain-level discrimination [6]. |

| Ability to Resolve Intragenomic Variation | No | Yes, can distinguish between multiple copies of the 16S gene within a single genome [6]. |

| Cost & Throughput | Lower cost per sample; very high throughput. | Higher cost per sample; lower throughput. |

| Error Profile | Low substitution errors. | Higher initial error rate, corrected via circular consensus sequencing (CCS) to >99.9% accuracy [6]. |

A 2019 study in Nature Communications demonstrated that the V4 region alone failed to confidently classify 56% of in-silico amplicons to the species level, whereas full-length sequences successfully classified nearly all sequences correctly [6]. Furthermore, full-length sequencing allows for the detection of intragenomic variation (sequence differences between multiple 16S gene copies in a single genome), which can provide additional strain-level resolution [6].

Selection of Hypervariable Regions

When full-length sequencing is not feasible, the choice of hypervariable region significantly impacts outcomes. Research indicates that the V1-V3 region often provides a resolution closest to that of the full-length gene for many applications, including skin microbiome studies [12]. Other regions, like V6-V8, also show high precision for specific environments like the gut [15]. It is critical to avoid regions known to perform poorly for your sample type; for example, the V4-V5 region should be avoided in infant fecal samples [15].

Limitations and Complementary Approaches

While powerful, 16S rRNA sequencing has limitations:

- Species-Level Ambiguity: Closely related species (e.g., E. coli and Shigella) may have identical or nearly identical 16S sequences [11].

- Multi-Copy Number Bias: The number of 16S gene copies per genome varies between taxa, potentially skewing abundance estimates [11].

- Lack of Functional Insight: The technique reveals "who is there" but not "what they are doing" [13] [11].

For functional analysis, shotgun metagenomic sequencing is the recommended complementary approach. It provides comprehensive insights into the functional potential of the community by sequencing all genomic DNA, allowing for the reconstruction of metabolic pathways and the identification of genes related to virulence and antibiotic resistance [13].

The 16S rRNA gene remains an indispensable tool in microbial ecology and drug development due to its unique properties as a molecular chronometer. Its universal distribution, structural combination of conserved and variable regions, and slow evolutionary rate provide a robust framework for phylogenetic analysis. Current best practices involve leveraging full-length gene sequencing where possible to maximize taxonomic resolution, or carefully selecting the most informative variable regions (e.g., V1-V3) for short-read platforms. By understanding the principles outlined in this application note and adhering to the detailed protocols, researchers can reliably harness the power of 16S rRNA gene sequencing to uncover the composition and dynamics of microbial communities, thereby accelerating discovery in basic research and therapeutic development.

The 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene is a cornerstone of microbial ecology and microbiome research, serving as a reliable genetic marker for profiling bacterial and archaeal communities. This ~1500 base-pair gene contains a unique architecture of highly conserved regions interspersed with nine hypervariable regions (V1-V9) that evolve at different evolutionary rates, enabling both universal amplification and taxonomic discrimination [6] [16]. Furthermore, its multi-copy nature within prokaryotic genomes introduces important considerations for quantitative interpretation. These key characteristics collectively establish the 16S rRNA gene as an powerful tool for microbial classification, though they also necessitate careful methodological considerations during experimental design and data analysis. This application note details these fundamental properties and provides structured protocols for researchers investigating microbial communities across various sample types.

Key Characteristics and Technical Data

Conserved and Variable Region Architecture

The 16S rRNA gene comprises nine variable regions (V1-V9) separated by conserved segments, with the conserved regions enabling universal primer binding for PCR amplification across diverse bacterial taxa, while the variable regions provide the sequence divergence necessary for taxonomic discrimination [6] [16]. The relative positions of these regions within the approximately 1500 bp gene are illustrated below:

Different hypervariable regions offer varying levels of taxonomic resolution, and their selection significantly impacts experimental outcomes. The table below summarizes the comparative performance of commonly targeted regions:

Table 1: Taxonomic resolution and performance characteristics of 16S rRNA hypervariable regions

| Target Region | Approximate Length (bp) | Recommended Applications | Taxonomic Resolution | Limitations and Biases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1-V2 | ~350 | Respiratory microbiota [17], Streptococcus and Staphylococcus discrimination [17] | High for specific pathogens | Underrepresents Proteobacteria [6] |

| V3-V4 | ~460 | Human gut microbiome studies [18], general purpose | Good genus-level resolution | Poor for Actinobacteria [6] |

| V4 | ~250 | General environmental studies | Moderate genus-level resolution | Lowest discriminatory power (56% accurate species classification) [6] |

| V6-V8 | ~400 | Clostridium and Staphylococcus detection [6] | Varies by taxon | Limited validation across environments |

| V7-V9 | ~350 | Specific taxonomic groups | Lower diversity estimates [17] | Significantly reduced alpha diversity [17] |

| Full-length (V1-V9) | ~1500 | Species- and strain-level resolution [6] [19], clinical biomarkers [19] | Highest species/strain resolution | Higher cost, specialized platform required |

Multi-Copy Nature and Gene Copy Number Variation

A critical yet often overlooked characteristic of the 16S rRNA gene is its presence in multiple copies within a single bacterial genome, with copy numbers ranging from 1 to 21 across different taxa [20]. This multi-copy nature has profound implications for quantitative interpretation of 16S rRNA sequencing data, as abundance measurements reflect gene copy counts rather than actual cell numbers [20]. The diagram below illustrates this concept and its bioinformatic correction:

The table below compares main approaches for addressing 16S rRNA gene copy number variation:

Table 2: Methods for 16S rRNA gene copy number (16S GCN) estimation and correction

| Method Category | Examples | Underlying Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taxonomy-Based | rrnDB [20], RDP [20] | Assigns average GCN based on taxonomic classification | Simple implementation, fast computation | Limited by classification accuracy and database completeness |

| Phylogeny-Based | PICRUSt2 [20] | Infers GCN from evolutionary relationships in phylogenetic trees | Accounts for evolutionary relationships | Dependent on reference tree quality and topology |

| Deep Learning | ANNA16 [20] | Predicts GCN directly from 16S sequence using neural networks | High accuracy, avoids classification steps | Computationally intensive, requires training data |

Application Notes and Experimental Protocols

Full-Length 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing for Enhanced Taxonomic Resolution

Principle: Third-generation sequencing platforms (PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) enable sequencing of the entire ~1500 bp 16S rRNA gene, capturing all variable regions and providing superior taxonomic resolution compared to short-read approaches targeting partial regions [6] [19] [21].

Experimental Workflow:

Step-by-Step Protocol:

DNA Extraction

Full-Length 16S Amplification

- Primer Design: Target conserved regions flanking V1-V9 (e.g., 27F: AGRGTTYGATYMTGGCTCAG; 1492R: RGYTACCTTGTTACGACTT) [21].

- PCR Reaction: Use high-fidelity polymerase (e.g., KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix) with 20-27 cycles to minimize chimera formation [21].

- Cycling Conditions: 95°C for 3 min; 20-27 cycles of [95°C for 30s, 55-57°C for 30s, 72°C for 60s]; final extension at 72°C for 5 min [21].

Library Preparation and Sequencing

Bioinformatic Processing

- Demultiplex samples and generate CCS reads (PacBio) or basecall raw signals (Nanopore).

- Process sequences using DADA2 (QIIME2 plugin) for quality filtering, error correction, and amplicon sequence variant (ASV) inference [21].

- For Nanopore data, consider specialized tools like Emu that account for higher error rates [19].

- Perform taxonomic assignment using reference databases (SILVA, Greengenes) with species-level thresholds [16].

Hypervariable Region Selection for Specific Research Applications

Principle: Different hypervariable regions exhibit varying discriminatory power for specific bacterial taxa and sample types. Optimal region selection enhances detection sensitivity and taxonomic accuracy for particular research questions [17] [16].

Protocol for Region Selection and Validation:

Define Research Objectives and Expected Taxa

- Identify target microorganisms of interest and their relative abundance in sample type.

- Consult literature and database (e.g., SILVA TestPrime) for primer coverage evaluation [16].

Select Appropriate Hypervariable Region

- Respiratory Samples: Prioritize V1-V2 region, which demonstrates highest sensitivity and specificity (AUC: 0.736) for respiratory microbiota [17].

- Human Gut Microbiome: Consider V3-V4 region, well-established for gastrointestinal taxa with extensive reference databases [18].

- Species-Level Discrimination: Implement full-length V1-V9 sequencing when distinguishing closely related species (e.g., Escherichia coli vs. Shigella) [6] [21].

Wet-Lab Validation with Mock Communities

- Include mock community standards (e.g., ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community) in sequencing runs.

- Compare theoretical vs. observed composition to calculate recall, precision, and F-measure for each primer set [16].

- Validate detection limits for low-abundance taxa of interest.

Bioinformatic Optimization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential reagents and materials for 16S rRNA gene sequencing studies

| Category | Specific Product/Kit | Application Note | Critical Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction | QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit [21] | Optimal for tough-to-lyse gram-positive bacteria in stool | Comprehensive cell lysis and inhibitor removal |

| PCR Amplification | KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix [21] | Essential for full-length 16S amplification with high fidelity | Reduces PCR errors and chimera formation |

| Library Prep | SMRTbell Prep Kit (PacBio) [21] | Required for circular consensus sequencing | Enables template preparation for long-read platforms |

| Quality Control | ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standard [17] [21] | Mandatory for validating entire workflow performance | Identifies technical biases and quantifies accuracy |

| Sequencing | PacBio Sequel IIe System [21] | Recommended for high-throughput full-length 16S | Generates HiFi reads with Q30 quality for species ID |

| Bioinformatic Tools | DADA2 (QIIME2 plugin) [21] | Optimal for Illumina and PacBio CCS data | Precisely resolves amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) |

| Reference Databases | SILVA database [22] [16] | Continuously updated with quality-controlled sequences | Provides accurate taxonomic nomenclature framework |

The triumvirate of conserved regions, nine hypervariable domains, and multi-copy nature establishes the 16S rRNA gene as both a powerful and complex tool for microbial analysis. Researchers must strategically select hypervariable regions based on their specific sample type and research questions, recognizing that full-length sequencing provides superior taxonomic resolution while targeted regions offer cost-effective alternatives for well-characterized systems. Crucially, accounting for 16S rRNA gene copy number variation through bioinformatic correction is essential for accurate quantitative interpretation. As sequencing technologies continue to advance, particularly in long-read platforms, the full potential of 16S rRNA gene analysis is increasingly realizable, promising enhanced discriminatory power for clinical diagnostics, biomarker discovery, and fundamental microbial ecology research.

The 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene has served as the cornerstone of microbial phylogenetics and ecology for nearly half a century. This application note traces the revolutionary journey from Carl Woese's pioneering phylogenetic work to contemporary high-throughput sequencing protocols that enable comprehensive microbiome analysis. The 16S rRNA gene is universally present in bacteria and archaea, contains both highly conserved regions for primer binding and hypervariable regions providing species-specific signatures, and evolves at a rate that makes it ideal for measuring evolutionary relationships [1]. Understanding this historical context and technical evolution is essential for researchers designing robust microbiome studies in drug development, clinical diagnostics, and environmental monitoring.

Historical Foundation: Carl Woese's Phylogenetic Revolution

Pioneering Work in Molecular Phylogeny

In 1977, Carl Woese and George E. Fox pioneered the use of 16S rRNA for phylogenetic studies, fundamentally reshaping our understanding of the tree of life by revealing a previously unknown domain—Archaea [1]. Woese recognized that the 16S rRNA gene's molecular clock-like nature and universal distribution made it an ideal phylogenetic marker for comparing evolutionary relationships across all life forms [8]. His work established that the degree of sequence difference in the 16S rRNA gene correlated with evolutionary distance, enabling the reconstruction of phylogenetic relationships between diverse microorganisms.

Woese's comparative analysis approach was groundbreaking. In early work on 5S rRNA, he and George Fox demonstrated that by comparing sequences from just six different bacteria, they could deduce a common secondary structure compatible with all sequences [23]. This comparative method became the foundation for determining the secondary structure of the much larger 16S rRNA through compensating base change analysis, where helices were "proven" by finding two or more compensating base changes between organisms without non-compensated changes [23].

Technical Challenges in Early 16S rRNA Analysis

Early 16S rRNA analysis faced tremendous technical challenges before the advent of modern sequencing technologies. As Harry Noller's account reveals, determining the secondary structure of the ~1500-nucleotide 16S rRNA presented formidable obstacles. Computational predictions alone were insufficient, with estimates suggesting approximately 10,000 possible helices of four or more base pairs, corresponding to a staggering 10^115 possible secondary structures—far exceeding the number of fundamental particles in the known universe [23].

The collaboration between Woese and Noller to determine the 16S rRNA secondary structure relied on T1 RNase oligonucleotide catalogs from approximately 100 different bacteria. However, because T1 RNase cleaves at G residues and most RNA helices are G-rich, the oligonucleotides were often too short to assign to unique positions, yielding only around eight "proven" helices initially [23]. This limitation necessitated obtaining complete 16S rRNA sequences from divergent organisms such as Bacillus brevis and Halobacterium volcanii, which required heroic efforts including direct RNA sequencing and specialized gel methods when cloning proved difficult [23].

Technical Considerations and Limitations of 16S rRNA Sequencing

Phylogenetic Discordance and Genomic Heterogeneity

Despite its widespread use, modern research has revealed important limitations of the 16S rRNA gene as a phylogenetic marker. A critical 2022 study demonstrated that 16S rRNA gene phylogenies lack concordance with core genome phylogenies at both intra- and inter-genus levels [8]. At the intra-genus level, the 16S rRNA gene showed one of the lowest levels of concordance with core genome phylogeny (50.7% average), and was found to be recombinant and subject to horizontal gene transfer [8].

This phylogenetic discordance has far-reaching implications:

- Incorrect species/strain delineation and phylogenetic inference

- Confounded community diversity metrics when phylogenetic information is incorporated (e.g., Faith's phylogenetic diversity, UniFrac)

- Limited resolution for closely related species that share up to 99% sequence similarity [1]

The presence of multiple 16S rRNA gene copies within single genomes (ranging from 1-27 copies) [8] with intraspecies heterogeneity [1] further complicates abundance estimations and can lead to PCR-induced chimeras.

Primer Selection and Amplification Bias

Primer selection represents a critical source of variability in 16S rRNA gene-based microbiome profiling. Even minor mismatches between primer sequences and target regions can introduce substantial amplification bias, preferentially enriching certain taxa while underrepresenting others [24]. This bias affects both alpha and beta diversity measures and can distort downstream taxonomic assignments.

A 2025 comparative analysis of full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing in human oropharyngeal swabs demonstrated that primer degeneracy significantly impacts microbial community composition and diversity estimates [24]. The study compared two primer sets with differing degrees of degeneracy and found:

- The more degenerate primer set (27F-II) yielded significantly higher alpha diversity (Shannon index: 2.684 vs. 1.850; p < 0.001)

- The degenerate primer detected a broader range of taxa across all phyla

- Taxonomic profiles from the degenerate primer showed strong correlation with reference datasets (r = 0.86) compared to weak correlation with standard primers (r = 0.49)

- The standard primer (27F-I) overrepresented Proteobacteria and underrepresented key genera including Prevotella, Faecalibacterium, and Porphyromonas [24]

Table 1: Impact of Primer Degeneracy on Taxonomic Classification in Oropharyngeal Swabs

| Metric | Standard Primer (27F-I) | Degenerate Primer (27F-II) | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shannon Diversity Index | 1.850 | 2.684 | p < 0.001 |

| Correlation with Reference Dataset | r = 0.49 (p = 0.06) | r = 0.86 (p < 0.0001) | Significant improvement |

| Proteobacteria Representation | Overrepresented | Balanced | - |

| Key Genera Detection | Underrepresented Prevotella, Faecalibacterium, Porphyromonas | Appropriate detection | - |

Modern Sequencing Platforms and Methodological Approaches

Comparison of Short-Read vs. Long-Read Technologies

Current 16S rRNA sequencing approaches primarily utilize two platform types: short-read (e.g., Illumina) and long-read (e.g., Oxford Nanopore Technologies, PacBio) technologies. Each offers distinct advantages and limitations for microbiome analysis.

Table 2: Comparison of 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing Platforms and Approaches

| Parameter | Illumina (Short-Read) | Oxford Nanopore (Long-Read) |

|---|---|---|

| Target Region | Partial hypervariable regions (typically V3-V4, ~400-500 bp) | Full-length 16S rRNA gene (V1-V9, ~1500 bp) |

| Taxonomic Resolution | Primarily genus-level | Species-level and sometimes strain-level |

| Read Length | 75-300 bp | Up to 15 kb |

| Error Rate | ~0.1% (Q30) | Recently improved to ~1% (Q20) with R10.4.1 chemistry |

| Primary Applications | Large-scale microbiome surveys, diversity studies | Biomarker discovery, pathogen identification, clinical diagnostics |

| Throughput | High | Medium to high |

| Cost | Moderate | Decreasing |

Short-read sequencing (Illumina) has become the most widely used approach in large-scale microbiome studies due to its high base-calling accuracy and established analysis pipelines [24]. However, its limited read length typically restricts analyses to partial hypervariable regions (most commonly V3-V4 or V4), constraining taxonomic classification primarily to the genus level and complicating comparisons across studies that target different regions [24].

Long-read sequencing technologies such as Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) overcome this limitation by generating substantially longer reads, enabling full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing and improving phylogenetic resolution [24]. While ONT sequencing was initially hindered by higher error rates (~6%), continuous improvements in flow cell design (R10.4.1), sequencing chemistry (Q20+ kits), and basecalling algorithms have markedly improved accuracy, now achieving modal read accuracies below 1% error [24] [19].

Bioinformatic Analysis Tools and Databases

The evolution of sequencing technologies has been paralleled by development of specialized bioinformatic tools for data analysis:

- Kraken 2 and KrakenUniq: Rapid taxonomic classification tools based on k-mer matching. KrakenUniq provides more accurate abundance estimates with lower false-positive rates, making it preferable for clinical diagnostics [25].

- Emu: A relative abundance estimation method designed for noisy long-read 16S rRNA data [19].

- DADA2: Popular for Amplicon Sequence Variant (ASV) inference from high-quality Illumina reads [19].

Database selection significantly influences taxonomic classification accuracy. A 2025 study comparing SILVA versus Emu's default database found that Emu's database obtained significantly higher diversity and identified species but sometimes overconfidently classified unknown species as the closest match due to its database structure [19].

Diagram 1: 16S rRNA gene sequencing workflow with critical decision points highlighted in red and potential biases in yellow.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Full-Length 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing with Oxford Nanopore

Protocol: Full-length 16S rRNA gene amplification and sequencing using Oxford Nanopore Technology

Materials:

- Quick-DNA HMW MagBead kit (Zymo Research) or equivalent for DNA extraction

- Oxford Nanopore 16S Barcoding Kit (SQK-RAB204)

- Degenerate primers: 27F-II (5'-AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG-3') and 1492R (5'-CGGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3') [24]

- NanoDrop spectrophotometer and Quantus Fluorometer for quality control

- Oxford Nanopore MinION Mk1C with R10.4.1 flow cells

Procedure:

- Sample Collection and DNA Extraction:

- Collect samples using appropriate methods (e.g., oropharyngeal swabs transferred to DNA/RNA shielding buffer)

- Extract DNA using magnetic bead-based methods according to manufacturer's instructions

- Assess DNA purity (A260/A280 ratio ~1.8-2.0) and concentration using spectrophotometry and fluorometry

PCR Amplification:

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Prepare sequencing library according to ONT 16S barcoding kit protocol

- Load library onto MinION Mk1C with R10.4.1 flow cell

- Sequence for 24-48 hours using real-time basecalling

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Perform taxonomic classification using Emu with default database or SILVA

- Utilize Dorado basecaller (super-accurate model recommended) [19]

V3-V4 16S rRNA Sequencing with Illumina

Protocol: V3-V4 hypervariable region sequencing using Illumina MiSeq

Materials:

- EZ1 Virus Mini kit v2.0 (Qiagen) or equivalent for DNA extraction

- KAPA HiFi DNA polymerase (Roche)

- Illumina adapter-containing primers: 341F (5'-CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3') and 785R (5'-GACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC-3') [25]

- MiSeq Reagent Kit v3 (600-cycle)

Procedure:

- DNA Extraction and Quality Control:

- Extract DNA with additional proteinase K pretreatment (56°C for 60 min)

- Quality check using TapeStation system

PCR Amplification:

- Prepare reaction: 12.5 μL KAPA HiFi DNA polymerase, 0.5 μL each primer, 1.5 μL nuclease-free water, 10 μL DNA template

- Cycling conditions: 95°C for 3 min; 45 cycles of: 95°C for 30s, 55°C for 30s, 72°C for 30s; final extension at 72°C for 5 min [25]

- Verify amplicons (~550 bp) using TapeStation

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Prepare library following Illumina 16S Metagenomic Sequencing Protocol with modifications for small 500-cycle nano-flow cell

- Sequence on MiSeq platform with 2×250 bp paired-end reads

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Process sequences using DADA2 pipeline in QIIME2 for ASV inference

- Classify taxa using SILVA database

- Calculate diversity metrics (alpha and beta diversity)

Applications in Drug Development and Clinical Research

Biomarker Discovery and Precision Medicine

Full-length 16S rRNA sequencing has demonstrated significant advantages in biomarker discovery for disease detection and monitoring. A 2025 study on colorectal cancer (CRC) biomarkers compared Illumina-V3V4 with ONT-V1V9 sequencing and found that Nanopore sequencing identified more specific bacterial biomarkers for colorectal cancer, including Parvimonas micra, Fusobacterium nucleatum, Peptostreptococcus stomatis, Peptostreptococcus anaerobius, Gemella morbillorum, Clostridium perfringens, Bacteroides fragilis, and Sutterella wadsworthensis [19].

The study demonstrated that prediction of colorectal cancer through machine learning achieved an AUC of 0.87 with 14 species or 0.82 with just 4 species (P. micra, F. nucleatum, B. fragilis and Agathobaculum butyriciproducens), highlighting the potential for developing non-invasive diagnostic tests based on microbiome biomarkers [19].

Pharmaceutical Impact Assessment on Microbiomes

16S rRNA gene sequencing plays a crucial role in assessing the impact of pharmaceuticals on microbial communities, particularly in environmental risk assessment. Studies applying 16S rRNA sequencing have confirmed that pharmaceuticals, including antibiotics, NSAIDs, antidepressants, and complex mixtures, induce significant shifts in microbial community structure, reducing alpha diversity and enriching resistant taxa and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) genes [26].

This application is particularly relevant for drug development, where understanding the ecological impact of pharmaceutical compounds and their metabolites is essential for comprehensive risk assessment. The method enables monitoring of treatment effects on human microbiomes and environmental microbial communities exposed to pharmaceutical contamination through wastewater and agricultural practices [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for 16S rRNA Sequencing Studies

| Item | Function | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | High-quality DNA extraction from diverse sample types | Quick-DNA HMW MagBead kit (Zymo Research), EZ1 Virus Mini kit (Qiagen) with proteinase K pretreatment |

| Universal Primers | Amplification of 16S rRNA gene regions | 27F/1492R (full-length), 341F/785R (V3-V4); Degenerate versions recommended to reduce bias |

| Polymerase | High-fidelity PCR amplification | KAPA HiFi DNA Polymerase (Roche) for Illumina; ONT 16S Barcoding Kit for Nanopore |

| Sequencing Platforms | Generating sequence data | Illumina MiSeq (short-read), Oxford Nanopore MinION Mk1C (long-read) |

| Flow Cells/Chemistry | Platform-specific sequencing | Illumina MiSeq Reagent Kit v3; ONT R10.4.1 flow cells with Q20+ chemistry |

| Reference Databases | Taxonomic classification | SILVA, Greengenes, RDP; Emu's default database for Nanopore data |

| Bioinformatic Tools | Data processing and analysis | KrakenUniq, Emu, DADA2 (QIIME2), Dorado basecaller |

Diagram 2: Evolution of 16S rRNA sequencing technologies and capabilities over time.

The journey from Carl Woese's pioneering phylogenetic work to modern high-throughput 16S rRNA sequencing has transformed microbial ecology and opened new avenues for drug development and clinical diagnostics. While methodological challenges remain—including amplification biases, phylogenetic discordance, and database limitations—recent advances in long-read sequencing, degenerate primer design, and bioinformatic tools are steadily addressing these limitations.

Future developments will likely focus on integrating multi-omics approaches (metagenomics, metatranscriptomics) with 16S rRNA data to move beyond census-based information and truly understand functional responses to pharmaceutical interventions [26]. Standardization of methodologies and continued improvement in sequencing accuracy will further enhance the value of 16S rRNA sequencing in drug development pipelines, environmental risk assessment, and personalized medicine applications.

For researchers in drug development, the current state of 16S rRNA sequencing offers robust approaches for microbiome biomarker discovery, pharmaceutical impact assessment, and personalized therapeutic strategies based on individual microbiome profiles. By understanding both the historical context and technical considerations outlined in this application note, scientists can design more rigorous microbiome studies that account for methodological limitations while leveraging the full potential of this transformative technology.

The 16S rRNA Gene as a Universal Barcode for Bacterial and Archaeal Life

The 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene has served as a cornerstone for microbial ecology and identification for decades. This ~1,500 base-pair gene is found in all bacteria and archaea, and its structure—comprising nine hypervariable regions (V1-V9) interspersed with conserved sequences—makes it an ideal target for phylogenetic studies [27] [28]. The conserved regions enable the design of broad-range PCR primers, while the variable regions provide the nucleotide diversity necessary to discriminate between different taxonomic groups [27]. Consequently, 16S rRNA gene sequencing has become the method of choice for characterizing the composition of microbial communities from diverse environments, including the human body, soil, water, and industrial systems [27] [29].

This Application Note frames the use of the 16S rRNA gene within the context of a broader thesis on microbiome analysis protocols. It is designed to provide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a detailed overview of the principles, applications, and detailed methodologies for using this universal barcode, including optimized experimental protocols and advanced data analysis considerations.

Principles and Applications of 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

The 16S rRNA gene functions as a molecular clock due to its essential role in protein synthesis, which constrains its sequence from changing too rapidly. However, the hypervariable regions accumulate mutations at a rate that provides sufficient resolution for phylogenetic classification. This allows for the identification and relative quantification of bacteria and archaea present within a complex sample without the need for cultivation [27].

The typical workflow involves several key steps: sample collection and DNA extraction, PCR amplification of the 16S rRNA gene using primers targeting specific variable regions, library preparation, high-throughput sequencing, and bioinformatic analysis [27].

Table 1: Key Applications of 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing Across Fields

| Field | Primary Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental Microbiology | Identification and classification of microorganisms in natural environments; assessment of diversity, pollution, and contamination. | Analysis of soil, water, and air samples [27]. |

| Medical Microbiology | Diagnosis and treatment of infections; insights into the role of the microbiome in health and disease. | Characterization of human gut, skin, and oral microbiomes; analysis of clinical samples from infected tissues [27] [30]. |

| Food Microbiology | Ensuring food safety and quality; screening for food-borne pathogens. | Analysis of fermented foods and beverages [27]. |

| Industrial Microbiology | Monitoring and optimizing industrial processes. | Production of biotechnology products and pharmaceuticals; wastewater treatment [27]. |

| Forensic Science | Individual identification and tracing the origin of biological evidence. | Analysis of skin ("touch microbiome") and soil microbial communities [29]. |

Critical Methodological Considerations

The accuracy and reliability of 16S rRNA gene sequencing results are highly dependent on several factors throughout the experimental pipeline. Researchers must make informed choices at each step to ensure their data is robust and interpretable.

Primer Selection and Variable Region Choice

The selection of PCR primers targeting specific variable regions is one of the most critical decisions, as it directly influences coverage, specificity, and taxonomic resolution [16] [31]. Different variable regions possess varying degrees of discriminatory power for different bacterial phyla.

- Coverage vs. Specificity: "Universal" primer pairs (e.g., 515F-806R targeting the V4 region) are designed to amplify a wide range of bacteria but may poorly amplify or miss specific groups, including many archaea [16] [32]. For example, the V4 region is a popular target but has been shown to miss certain Bacteroidetes when using the 515F-944R primer pair [16]. Specialist primers, such as those newly designed for Archaea (e.g., SSU1ArF/SSU1000ArR), can provide much higher coverage for these underrepresented domains [32].

- Taxonomic Resolution: Sequencing different variable regions can lead to significantly different microbial community profiles, even from the same donor sample [16]. While sequencing a single variable region (e.g., V4) is cost-effective, sequencing longer stretches spanning multiple regions (e.g., V1-V3 or V3-V4) generally improves taxonomic classification [6]. Full-length 16S gene sequencing (V1-V9) using third-generation platforms (PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) provides the highest possible resolution, enabling differentiation at the species and sometimes strain level [18] [6].

Table 2: Comparison of Commonly Targeted 16S rRNA Gene Variable Regions

| Target Region | Example Primer Pairs | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| V1-V2 | 27F-338R | Good resolution for certain taxa like Escherichia/Shigella [16] [6]. | Poor classification of Proteobacteria [6]. |

| V3-V4 | 341F-785R | Common, well-established region; good for gut microbiomes (Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes) [16] [18]. | Poor classification of Actinobacteria [6]. |

| V4 | 515F-806R | Highly popular; short length suitable for Illumina MiSeq; low error rate [33]. | Lowest species-level resolution; can miss key taxa [16] [6]. |

| V6-V8 | 939F-1378R | Good for classifying Clostridium and Staphylococcus [6]. | Less commonly used. |

| Full-length (V1-V9) | 27F-1492R | Highest species and strain-level resolution; identifies intragenomic sequence variants [6]. | Higher cost and longer sequencing time [18]. |

Bioinformatics and Reference Databases

The bioinformatic processing of 16S sequencing data profoundly impacts the results. Key considerations include:

- Clustering Methods: Traditional Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) cluster sequences at a fixed similarity threshold (e.g., 97% for species). In contrast, Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) resolve sequences at a single-nucleotide level, providing higher resolution and improved cross-study comparability [16] [28].

- Reference Databases: Taxonomic assignment is only as good as the reference database used. Common databases include GreenGenes, SILVA, and the RDP. However, the use of niche-specific databases (e.g., the Human Oral Microbiome Database - HOMD) has been shown to improve classification accuracy by aligning reference sequences more closely with the microbial community under investigation [30] [28].

- Dynamic Thresholding: The use of a fixed identity threshold (e.g., 98.5-99%) for species-level classification can lead to misidentification. Implementing flexible, species-specific thresholds has been demonstrated to significantly improve classification accuracy [18].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Sample Collection, Preservation, and DNA Extraction

Principle: The goal is to obtain high-quality, uncontaminated genomic DNA that accurately represents the microbial community.

Protocol (for human fecal samples):

- Collection: Collect samples using a provided sterile collection kit. For fecal samples, use a sterile spoon or swab to transfer material into a sterile container.

- Preservation: Immediate freezing at -20°C or -80°C is critical to preserve the microbial composition. Avoid freeze-thaw cycles. If immediate freezing is not possible, temporarily store samples at 4°C for a few hours or use a commercial preservation buffer [27].

- DNA Extraction:

- Use a commercially available DNA extraction kit suitable for the sample type (e.g., soil, stool, water).

- Lysis: Mechanically lyse cells using bead beating in a homogenizer (e.g., 40s at speed 6 m/s) combined with chemical lysis (e.g., SDS and enzymes) and heat (e.g., 2 min at 99°C). Freeze-thaw cycles may also be employed to enhance lysis [33].

- Precipitation and Purification: Add a salt solution and alcohol to precipitate DNA. Purify the DNA using spin columns or magnetic beads to remove impurities, proteins, and inhibitors. Elute DNA in nuclease-free water or TE buffer [27].

- Quantification: Quantify the extracted DNA using a fluorometric method (e.g., Qubit dsDNA HS Assay) [33].

Critical Step: Include a negative control (no sample) during the extraction and a positive control (e.g., a mock microbial community with known composition) to monitor contamination and efficacy [27] [28].

Library Preparation for Illumina Sequencing (V3-V4 Region)

Principle: To amplify the target 16S region and attach Illumina sequencing adapters and dual indices (barcodes) to allow for multiplexing of samples.

Protocol (Adapted from Kozich et al., 2013 and subsequent modifications [33]):

- First-Stage PCR - Amplicon Generation:

- Primers: Use primers 341F (5'-CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3') and 785R (5'-GACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC-3') for the V3-V4 region.

- Reaction Mix (25µl):

- 2-12.5 ng genomic DNA

- 0.5 µM each forward and reverse primer

- 12.5 µL 2x HOT FIREPol Blend Master Mix (or equivalent high-fidelity PCR mix)

- Nuclease-free water to 25 µL.

- Thermocycler Conditions:

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 15 min.

- 25-30 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 30 s.

- Annealing: 55°C for 30 s.

- Extension: 72°C for 30 s.

- Final extension: 72°C for 5 min.

- Hold at 4°C.

- Primers: Use primers 341F (5'-CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3') and 785R (5'-GACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC-3') for the V3-V4 region.

- PCR Clean-up: Purify the amplicons using magnetic beads (e.g., AMPure XP beads) to remove primers, dimers, and non-specific products.

- Second-Stage PCR - Index Attachment:

- Reaction Mix (25µl):

- 5 µL purified first-stage PCR product.

- 5 µL of each P5 and P7 Illumina index primer.

- 12.5 µL 2x HOT FIREPol Blend Master Mix.

- Nuclease-free water to 25 µL.

- Thermocycler Conditions:

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 5 min.

- 8 cycles of: 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, 72°C for 30 s.

- Final extension: 72°C for 5 min.

- Hold at 4°C.

- Reaction Mix (25µl):

- Final Clean-up: Purify the indexed amplicons a second time with magnetic beads.

- Library QC and Normalization: Quantify the final library using a fluorometer, check the size distribution (expect ~550 bp for V3-V4) on a bioanalyzer or tape station, and pool libraries in equimolar amounts.

Figure 1: Workflow for 16S rRNA Amplicon Library Preparation. This diagram outlines the key steps in preparing a sequencing library, from initial amplification of the target region to the final pooled library.

Sequencing and Data Analysis

Sequencing: Sequence the pooled library on an Illumina MiSeq or MiniSeq platform using a 2x250 bp or 2x300 bp paired-end kit to adequately cover the V3-V4 amplicon [33].

Bioinformatic Analysis (using QIIME 2 and DADA2 [28]):

- Demultiplexing: Assign raw sequencing reads to samples based on their unique barcodes.

- Denoising and Generating ASVs: Use the DADA2 pipeline within QIIME 2.

- Trim primers and low-quality bases from reads.

- Learn and correct for Illumina sequencing errors.

- Merge paired-end reads.

- Remove chimeric sequences.

- The output is a feature table of Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) and their representative sequences.

- Taxonomic Assignment: Assign taxonomy to each ASV using a naive Bayesian classifier (e.g., the

classify-sklearnmethod in QIIME 2) against a reference database (e.g., SILVA or GreenGenes). - Diversity and Statistical Analysis:

- Alpha Diversity: Calculate within-sample diversity (e.g., Shannon index) using tools like phyloseq in R [28].

- Beta Diversity: Calculate between-sample diversity using metrics like Bray-Curtis dissimilarity or Weighted UniFrac. Visualize using PCoA plots.

- Differential Abundance: Test for significant differences in ASV abundance between sample groups using statistical models like the Linear Decomposition Model (LDM), which controls for multiple testing using False Discovery Rate (FDR) [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

| Item | Function/Description | Example Product/Note |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | Isolates microbial genomic DNA from complex samples. | MoBio PowerSoil Kit or equivalent; critical for lysis of tough cells [33]. |

| High-Fidelity PCR Master Mix | Amplifies 16S target region with low error rate. | HOT FIREPol Blend Master Mix; reduces PCR-derived sequence errors [33]. |

| Validated Primer Panels | PCR primers targeting specific hypervariable regions. | Panels for V3-V4 (341F/785R) or V4 (515F/806R); choice impacts results [16] [33]. |

| Magnetic Bead Clean-up Kit | Purifies PCR amplicons by removing impurities and small fragments. | AMPure XP Beads; used for size selection and clean-up [27]. |

| Mock Microbial Community | Control with known composition to assess sequencing accuracy. | ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standard; validates entire workflow [28]. |

| Sequencing Platform | High-throughput system for generating sequence data. | Illumina MiSeq/MiniSeq for short reads; PacBio Sequel for full-length [33] [6]. |

| Reference Database | Curated sequence collection for taxonomic assignment. | SILVA, GreenGenes, or niche-specific databases (e.g., HOMD) [30] [28]. |

Advanced Concepts and Future Directions

Species and Strain-Level Resolution

While full-length 16S sequencing significantly improves taxonomic resolution, a major advancement lies in the identification and utilization of intragenomic 16S copy variants [6]. Many bacterial genomes contain multiple copies of the 16S rRNA gene, and these copies can have slightly different sequences. High-accuracy, full-length sequencing can resolve these subtle nucleotide substitutions. Rather than collapsing these variants, treating them as a "haplotype" for a given strain can provide a powerful new dimension for discrimination, enabling tracking of specific strains within complex communities [6].

The Impact of Primer Design

The development of novel primers remains an active area of research. Computational methods like multi-objective optimization (e.g., mopo16S) are now being used to design primer-set-pairs that simultaneously maximize efficiency, coverage (the fraction of bacterial sequences targeted), and minimize primer matching-bias (differences in the number of primers matching each sequence) [31]. This is crucial for quantitative studies, as matching-bias can lead to over- or under-amplification of certain taxa. Furthermore, primer design is evolving to improve the detection of historically underrepresented groups, such as Archaea, by leveraging updated sequence databases to create primers with fewer mismatches [32].

Figure 2: Computational Pipeline for Optimized 16S Primer Design. This diagram illustrates the multi-objective optimization process for designing primer pairs that balance efficiency, coverage, and minimal bias.

Executing the 16S rRNA Sequencing Workflow: A Step-by-Step Protocol from Sample to Data

In 16S rRNA gene sequencing for microbiome analysis, the integrity of the entire study hinges on the initial steps of sample collection and preservation. Inappropriate handling during these early stages can introduce contamination and cause nucleic acid degradation, leading to biased or erroneous results that no sophisticated downstream analysis can rectify [27]. This is particularly critical when studying low-biomass environments (such as certain human tissues, water, and air), where the target microbial signal can be easily overwhelmed by contaminating DNA [34] [35]. This document outlines standardized protocols and critical considerations for the collection and preservation of samples, with the goal of preserving an accurate representation of the microbial community for reliable 16S rRNA sequencing.

Critical Considerations for Sample Collection

Contamination Prevention

Contaminating DNA from reagents, collection equipment, and personnel can critically impact sequence-based microbiome analyses, especially for low-biomass samples [35]. A contamination-aware mindset is essential throughout the collection process.

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Researchers should cover exposed body parts using gloves, goggles, coveralls or cleansuits, and shoe covers to prevent contamination from skin, hair, or aerosol droplets [34].

- Decontamination of Equipment: All tools, vessels, and surfaces that contact the sample should be decontaminated. A recommended procedure involves treatment with 80% ethanol to kill microorganisms, followed by a nucleic acid degrading solution (e.g., sodium hypochlorite/bleach, UV-C light, hydrogen peroxide) to remove residual DNA [34]. Whenever possible, use single-use, DNA-free consumables.

- Sample Controls: The inclusion of controls is non-negotiable for identifying contaminant sources. These should include:

- Negative controls: Empty collection vessels, swabs of the air in the sampling environment, aliquots of preservation solutions, and swabs of PPE or sampling surfaces [34].

- Positive controls: Mock microbial communities of known composition to assess the entire workflow's accuracy.

Sample Heterogeneity and Volume

- Stool Homogenization: For fecal samples, microbial profiles can differ between the inner and outer parts of the specimen [36]. Therefore, coarse homogenization of the entire stool sample is recommended before aliquoting to ensure a representative microbial analysis [36] [37].

- Sample Volume: The required volume is critical for obtaining sufficient DNA yield, particularly for low-biomass samples. While ~300 mg is often used for stool [36], larger volumes (e.g., 30–50 ml for catheter-collected urine) are recommended to ensure adequate DNA for sequencing [37].

Sample Preservation and Storage Methods

Immediate freezing at -80°C is the gold standard for preserving microbiome integrity [37]. However, this is often not feasible in remote or resource-limited fieldwork settings. The table below summarizes the performance of common preservation methods evaluated under realistic conditions.

Table 1: Comparison of Sample Preservation and Storage Methods

| Method | Typical Conditions | Impact on Microbiome Composition & Diversity | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immediate Freezing at -80°C | Frozen upon collection | Considered the "gold standard"; minimal changes | Laboratory settings where infrastructure is available [37] |

| Refrigeration at 4°C | Short-term storage (hours to ~2 weeks) | Effectively maintained microbial diversity; no significant difference from -80°C for fecal samples in one study [37] | Short-term storage when freezing is not immediately possible [27] [37] |

| Preservative Buffers (e.g., Ethanol, RNAlater, OMNIgene•GUT) | Ambient temperature for hours to days prior to freezing | Significant differences vs. immediate freezing, but intra-preservation technique variation is minimal; effective for consistent field collections [36] [37] | Fieldwork and large-scale studies where cold chain is unreliable [36] |

| Ambient Tropical Temperature (Time-to-Freezing) | 0–32 hours post-collection in shaded, ventilated areas | For preserved samples, variation across 0–32h time range was minimal, allowing for delayed freezing [36] | Real-world fieldwork in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [36] |

Key Findings from Fieldwork Studies

A Ugandan field study demonstrated that while the donor was the greatest source of microbiome variation, differences were observed between preservation methods (raw, ethanol, RNAlater) [36]. Critically, for a given preservation method, the variation was minimal across a time-to-freezing range of 0–32 hours at ambient tropical temperatures [36]. This finding provides a practical window for sample processing in challenging fieldwork conditions, so long as a consistent preservation method is used throughout a study.

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol: Testing Preservation Method Efficacy

To validate the impact of any preservation method on a specific sample type, the following comparative protocol can be employed.

- Objective: To evaluate the effectiveness of different preservation methods in maintaining microbial community integrity compared to the gold standard of immediate freezing.

- Materials:

- Fresh sample (e.g., stool, soil).

- Sterile collection tubes.

- Preservative buffers (e.g., absolute ethanol, RNAlater, OMNIgene•GUT).

- -80°C freezer or dry ice.

- Methodology:

- Sample Processing: Homogenize the fresh sample thoroughly. Aliquot into portions for each preservation condition and time point.

- Apply Preservation Conditions:

- Condition A (Gold Standard): Immediately freeze an aliquot on dry ice or at -80°C.

- Condition B (Refrigeration): Store an aliquot at 4°C for a defined period (e.g., 24, 48, 72 hours) before freezing.

- Condition C (Preservative Buffer): Add the sample to the recommended volume of preservative buffer (e.g., approx. 1:6 stool:ethanol ratio [36]) and store at ambient temperature for different time points (e.g., 0 h, 8 h, 24 h, 32 h) before freezing.

- DNA Extraction and Sequencing: After all samples have been transferred to -80°C, extract DNA from all samples in a single batch using a standardized kit (e.g., MPbio FastDNA SPIN Kit for Soil [36]) to avoid batch effects. Perform 16S rRNA gene sequencing (e.g., V4 region using 515F/806R primers [38]) on all libraries in a single sequencing run.

- Data Analysis: Analyze sequencing data using a standardized pipeline (e.g., QIIME 2). Compare alpha-diversity (e.g., Shannon Index) and beta-diversity (e.g., Bray-Curtis dissimilarity) between conditions. Statistical tests like PERMANOVA can determine if community compositions are significantly different between preservation methods and the gold standard [36].

Protocol: Contamination Monitoring During Collection

- Objective: To identify and account for contaminating DNA introduced during the sample collection process.

- Materials: Sterile swabs, empty collection vessels, DNA-free water.

- Methodology:

- Prepare Controls: During sample collection, prepare the following controls:

- Field Blank: Open a sterile collection vessel at the sampling site and then close it.

- Swab Control: Swab the gloves of the collector or a surface the sample may contact.

- Reagent Blank: Include an aliquot of the preservation solution used.

- Processing: Process these controls alongside the actual samples through every subsequent step, including DNA extraction, library preparation, and sequencing.

- Bioinformatic Subtraction: After sequencing, the taxa and sequences identified in these negative controls can be used to infer and subtract potential contaminants from the actual sample data using tools like

decontam[34].

- Prepare Controls: During sample collection, prepare the following controls:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Kits for Sample Collection and Preservation

| Item | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Degrading Solution | Destroys contaminating free DNA on surfaces and equipment | Decontaminating reusable sampling tools and work surfaces before collection [34] |

| Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) | Forms a physical barrier to prevent operator-derived contamination | Clean suits, gloves, masks, and shoe covers used during sampling of low-biomass environments [34] |