A Comprehensive Guide to Alpha and Beta Diversity Indices in Microbiome Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide to alpha and beta diversity indices, essential tools for analyzing microbial communities in microbiome research.

A Comprehensive Guide to Alpha and Beta Diversity Indices in Microbiome Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to alpha and beta diversity indices, essential tools for analyzing microbial communities in microbiome research. It covers foundational concepts, practical application methodologies, common troubleshooting and optimization strategies, and validation techniques. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the content synthesizes current best practices and emerging trends to enable robust and interpretable diversity analyses in studies of human health, disease, and therapeutic intervention.

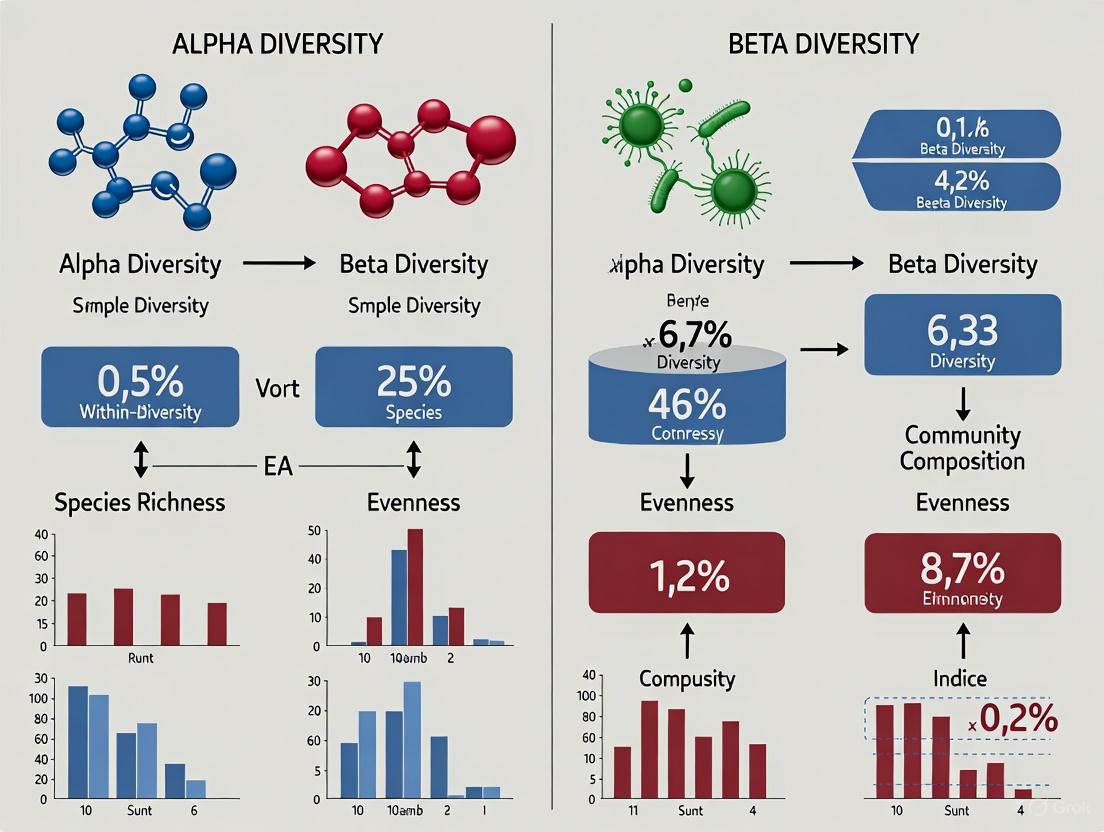

Demystifying Diversity: Core Concepts of Alpha and Beta Diversity

Defining Alpha, Beta, and Gamma Diversity in Ecological Context

In ecology, understanding the spatial distribution of species requires a framework that operates across different scales. Ecologist R. H. Whittaker provided this framework by introducing a trio of diversity measures: alpha (α), beta (β), and gamma (γ) diversity [1] [2] [3]. This conceptual model partitions the total species diversity in a landscape (gamma diversity) into two independent components: the mean species diversity within local sites (alpha diversity) and the differentiation in species composition among those sites (beta diversity) [1] [2]. The relationship between these components is fundamental to ecology, conservation biology, and modern microbiome research, providing insights into ecosystem health, resilience, and biogeographical patterns [4] [5]. The original formulation defined gamma diversity as the product of alpha and beta diversity (γ = α × β) [3], though additive partitioning (γ = α + β) is also used in some contexts [2]. These measures help researchers quantify how biodiversity is structured across spatial scales, from local habitats to entire regions.

Alpha Diversity: Local Species Variety

Core Concept and Definition

Alpha diversity is defined as the species diversity within a specific site or ecosystem at a local scale [1] [4]. It provides a measure of the variety of organisms found in a particular habitat, considering both the number of species (richness) and their relative abundance (evenness) [6]. High alpha diversity typically indicates a healthy, resilient ecosystem that can withstand environmental changes, while low alpha diversity may signal ecological stress or degradation [4]. As a fundamental measure in community ecology, it allows comparisons between different local habitats and serves as a baseline for understanding broader biodiversity patterns.

Key Metrics and Calculations

Alpha diversity can be quantified using various indices, each with distinct mathematical approaches and ecological interpretations. These metrics are broadly categorized into four groups: richness, dominance (evenness), phylogenetic, and information metrics [7].

Table 1: Key Alpha Diversity Metrics and Their Applications

| Metric Category | Example Metrics | Description | Ecological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Richness | Chao1, ACE, Observed Features [7] [6] | Estimates the number of species present in a sample. | Higher values indicate more species present; simple count measure. |

| Dominance/Evenness | Simpson, Berger-Parker, Gini [7] | Measures the distribution of abundances among species. | High evenness = similar species abundances; high dominance = few species dominate. |

| Phylogenetic | Faith's PD [7] | Incorporates evolutionary relationships between species. | Higher values indicate greater evolutionary history represented in community. |

| Information Theory | Shannon, Brillouin, Pielou [7] [6] | Based on entropy concepts from information theory. | Accounts for both richness and evenness; sensitive to rare species. |

The mathematical formulations for key alpha diversity indices include:

- Chao1 Richness Estimator: Schao1 = Sobs + (n1²/(2×n2)) where Sobs is the number of observed species, n1 is the number of singleton species, and n2 is the number of doubleton species [6]. This estimator accounts for unseen species based on rare species in the sample.

- Shannon Index: H' = -Σ(pi × ln(pi)) where pi is the proportion of individuals belonging to species i [6]. This index considers both species richness and evenness.

- Simpson Index: D = Σ(pi²) where pi is the proportion of individuals belonging to species i [6]. Often expressed as 1-D to represent diversity rather than dominance.

Scale Considerations and Limitations

A significant challenge in measuring alpha diversity relates to spatial scale. Both the landscape of interest and the sites within it may be of different sizes across studies, with no universal consensus on appropriate spatial scales for quantification [1]. It has been proposed that alpha diversity need not be tied to a specific spatial scale but can be measured for existing datasets with subunits at any scale [1]. However, researchers must note that species diversity in subunits typically underestimates diversity in larger areas, requiring careful interpretation when extrapolating beyond actual observations [1].

Beta Diversity: Species Composition Turnover

Core Concept and Definition

Beta diversity represents the ratio between regional and local species diversity, quantifying the change in species composition between different ecosystems or habitats [2] [8]. It measures how species diversity changes from one habitat to another, providing insights into spatial patterns of biodiversity and ecosystem variation [8]. Beta diversity essentially captures the extent of species turnover across environmental gradients or geographical distances, reflecting the differentiation among local sites within a broader region [2]. This measure helps ecologists understand how similar or dissimilar biological communities are across a landscape.

Quantification Approaches

Several formulations exist for quantifying beta diversity, each with distinct mathematical properties and ecological interpretations:

- Whittaker's Multiplicative Beta Diversity: β = γ/α, where gamma diversity is the total species diversity of a landscape and alpha diversity is the mean species diversity per site [2]. This represents the number of distinct communities in the region.

- Absolute Species Turnover: βA = γ - α, which partitions gamma diversity into additive components rather than multiplicative [2]. This quantifies how much more species diversity the entire dataset contains than an average subunit.

- Whittaker's Species Turnover: βW = (γ - α)/α = γ/α - 1, measuring how many times the species composition changes completely among subunits of the dataset [2]. With presence-absence data for two subunits, this equals one minus the Sørensen similarity index.

- Proportional Species Turnover: βP = (γ - α)/γ = 1 - α/γ, quantifying what proportion of the species diversity in the dataset is not contained in an average subunit [2]. For two subunits with presence-absence data, this measure equals one minus the Jaccard similarity index.

Table 2: Beta Diversity Indices and Their Characteristics

| Index Type | Formula | Range | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jaccard Similarity | J = C/(S1+S2-C) where C=shared species, S1&S2=total species per community [8] | 0-1 | Measures similarity based on shared species; ignores abundance. |

| Bray-Curtis Dissimilarity | BC = 1 - [2C/(S1+S2)] where C=sum of lesser abundances for each species [8] | 0-1 | Incorporates species abundance; more sensitive to compositional differences. |

| Sørensen Similarity | S = 2C/(S1+S2) where C=shared species, S1&S2=total species [2] | 0-1 | Similar to Jaccard but gives more weight to shared species. |

Analytical Methods for Beta Diversity

Several multivariate methods enable effective visualization and interpretation of beta diversity patterns:

- Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA): A visualization method for studying data similarity or dissimilarity that ranks data based on eigenvalues and eigenvectors [8]. Unlike PCA, PCoA can use various distance metrics beyond Euclidean distance to identify principal components influencing sample community composition differences.

- Non-Metric Multidimensional Scaling (NMDS): Simplifies high-dimensional objects into lower-dimensional space while preserving original relationships between objects [8]. This method is more accurate than PCA and PCoA with large sample sizes and works well with rank-order relationships rather than exact similarity measurements.

- Statistical Tests: PERMANOVA (Adonis) and ANOSIM assess the statistical significance of differences in community composition between predefined groups [8]. These tests determine whether observed separation between groups in ordination plots is statistically significant.

Gamma Diversity: Regional Species Pool

Core Concept and Definition

Gamma diversity represents the total species diversity within a specific geographical region or landscape, encompassing the variety of species found across different ecosystems throughout the area [3] [9]. This broad-scale diversity measure integrates both alpha diversity (within individual habitats) and beta diversity (between different habitats), providing a comprehensive overview of regional biodiversity [9]. Gamma diversity takes into account all species across various ecosystems in a defined area, making it particularly valuable for large-scale conservation planning and identifying regions with high species richness or endemism [9].

Scale Considerations and Measurement

As with alpha diversity, the area or landscape of interest for measuring gamma diversity may vary significantly across different studies without universal consensus on appropriate spatial scales [3]. Gamma diversity can be measured for existing datasets at any scale of interest, not necessarily tied to a specific spatial dimension [3]. However, researchers must consider that species diversity in a dataset generally underestimates actual diversity in larger areas, with the degree of underestimation increasing as the available sample size decreases relative to the area of interest [3]. This sampling effect can be estimated using species-area curves to extrapolate more accurate regional diversity estimates.

Calculation Methods

When species diversity is equated with the effective number of species, gamma diversity can be calculated using the following equation [3]:

qDγ = 1 / (Σpiq)(1/(q-1))

Where S is the total number of species (species richness) in the dataset, and pi is the proportional abundance of the ith species. The denominator equals the mean proportional species abundance in the dataset as calculated with the weighted generalized mean with exponent q-1. The parameter q determines the sensitivity of the measure to species abundances; larger values of q lead to smaller gamma diversity values because increasing q increases the weight given to species with the highest proportional abundance [3].

Research Applications and Protocols

Computational Analysis Workflow

Modern biodiversity research, particularly in microbiome studies, relies on standardized computational workflows for robust diversity analysis. The following diagram illustrates a typical workflow for processing amplicon sequencing data to calculate diversity metrics:

Microbiome Analysis Pipeline This workflow illustrates the standard bioinformatics processing of amplicon sequencing data (e.g., 16S rRNA) for diversity calculations, as implemented in pipelines like QIIME2 [10]. The process begins with raw sequence data, followed by demultiplexing to assign sequences to samples, quality filtering to remove low-quality reads, and denoising to correct sequencing errors and remove chimeras [10]. These steps produce a feature table (counts of operational taxonomic units or amplicon sequence variants) that serves as input for diversity calculations [7] [10]. Statistical analysis and visualization complete the interpretive process.

Experimental Findings in Microbial Ecology

Large-scale studies have revealed distinct patterns of bacterial diversity across different habitats. Analysis of 11,680 samples from the Earth Microbiome Project demonstrated that soils contained the highest bacterial richness within a single sample (alpha-diversity), but sediment assemblages displayed the highest gamma-diversity [5]. Sediment, biofilms/mats, and inland water exhibited the most variation in community composition among geographic locations (beta-diversity) [5]. Within soils, agricultural lands, hot deserts, grasslands, and shrublands contained the highest richness, while forests, cold deserts, and tundra biomes consistently harbored fewer bacterial species [5]. Surprisingly, agricultural soils encompassed similar levels of beta-diversity as other soil biomes, challenging assumptions about homogenization effects in managed ecosystems [5].

In human microbiome research, studies have demonstrated how demographic factors influence gut microbial diversity. Analysis of the American Gut Project dataset revealed significant age-related shifts in microbial richness and composition, while geographic location strongly influenced phylogenetic diversity [10]. In contrast, sex exhibited limited impact on microbial diversity within healthy BMI ranges, highlighting the differential effects of demographic variables on alpha and beta diversity patterns [10].

Essential Research Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Diversity Studies

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| 16S/18S/ITS rRNA Primers | Target conserved regions for amplicon sequencing | Taxonomic profiling of bacterial, eukaryotic, or fungal communities [8] [6] |

| QIIME2 Pipeline | Integrated bioinformatics platform | End-to-end processing of microbiome data from raw sequences to diversity analysis [7] [10] |

| Deblur/DADA2 | Denoising algorithms for sequence data | Error correction and production of amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) [7] [10] |

| GreenGenes/SILVA Databases | Curated rRNA sequence databases | Taxonomic classification of sequence variants [10] |

| Bray-Curtis Dissimilarity | Abundance-based distance metric | Quantifying community composition differences in beta diversity analysis [8] |

| Faith's PD | Phylogenetic diversity metric | Incorporating evolutionary relationships into diversity assessments [7] |

The conceptual framework of alpha, beta, and gamma diversity provides ecologists and microbiome researchers with powerful tools for quantifying biodiversity across spatial scales. Alpha diversity measures local-scale species variety, beta diversity quantifies compositional turnover between habitats, and gamma diversity captures the overall regional species pool [1] [2] [3]. Together, these measures offer complementary insights into how biodiversity is structured and maintained across landscapes. Current research continues to refine the application of these concepts, particularly in microbial ecology where standardized protocols and analytical workflows are enabling robust cross-study comparisons [7] [5]. As biodiversity assessment increasingly informs conservation priorities and ecosystem management, understanding the distinctions and interactions between these diversity components remains fundamental to ecological research and its applications in environmental science and human health.

In the field of microbial ecology, alpha diversity serves as a fundamental metric for quantifying the complexity of a microbial community within a single sample. It provides researchers and drug development professionals with a powerful tool to summarize the taxonomic distribution and abundance of microorganisms in a specific habitat. As one of the core components of diversity analyses—alongside beta diversity (between-sample differences) and gamma diversity (overall regional diversity)—alpha diversity offers critical insights into the ecological state of a microbiome [11]. The concept encompasses multiple dimensions of community structure, primarily focusing on species richness (the number of different taxa present) and evenness (the distribution of individuals among those taxa) [12]. Understanding these fundamental aspects enables researchers to ask crucial questions about their samples: How many different taxonomic groups are present? How evenly distributed are their abundances? And how does this internal diversity relate to environmental factors, health conditions, or therapeutic interventions?

The importance of alpha diversity extends beyond mere ecological description. In human microbiome studies, alterations in alpha diversity have been linked to various health states and disease conditions, making it a potential biomarker for clinical applications [7] [13]. For drug development professionals, monitoring alpha diversity can reveal how pharmaceutical interventions affect the microbial communities, potentially uncovering mechanisms of action or side effects. However, the complex nature of microbiome data—high-dimensional, sparse, and compositional—presents unique challenges for analysis and interpretation [13]. This technical guide provides a comprehensive framework for understanding, calculating, and interpreting alpha diversity metrics within the broader context of microbiome research, with particular emphasis on practical applications for scientific and clinical investigations.

Core Concepts and Mathematical Foundations

Defining Richness, Evenness, and Diversity

Alpha diversity metrics quantify different aspects of microbial community structure, each providing complementary information about the sample [14]. Richness represents the simplest dimension, referring to the number of distinct taxonomic units (such as operational taxonomic units or amplicon sequence variants) observed in a sample [15]. In contrast, evenness quantifies how equally abundant these different taxa are within the community [12]. A sample with perfect evenness would have all taxa represented by the same number of individuals, while an uneven sample would be dominated by one or a few taxa. The third concept, diversity itself, represents a composite measure that incorporates both richness and evenness into a single value, with different metrics weighting these components differently [14].

The mathematical foundation of alpha diversity metrics stems largely from ecological statistics, with many measures adapted from macroecology to microbiome studies [7]. These metrics can be broadly categorized into four classes based on what aspect of the community they capture: (1) richness estimators, which focus primarily on the number of taxa; (2) dominance metrics, which emphasize the abundance of the most common taxa; (3) information indices, which incorporate both richness and evenness based on information theory; and (4) phylogenetic measures, which incorporate evolutionary relationships between taxa [7] [14]. A comprehensive understanding of alpha diversity requires familiarity with metrics from each of these categories, as they capture different facets of community structure that may respond differently to environmental perturbations or clinical interventions.

Taxonomy of Alpha Diversity Metrics

Table 1: Categories and Key Metrics of Alpha Diversity

| Category | Representative Metrics | Primary Aspect Measured | Typical Value Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Richness | Observed Features, Chao1, ACE | Number of distinct taxa | 0 to hundreds (theoretical maximum varies) |

| Dominance | Berger-Parker, Simpson, Gini | Concentration of abundance in few taxa | 0-1 (for most indices) |

| Information | Shannon, Brillouin, Pielou's Evenness | Combination of richness and evenness | Shannon: typically 1-3.5, theoretically 0-∞ |

| Phylogenetic | Faith's Phylogenetic Diversity | Evolutionary divergence among taxa | 0-∞ (depends on branch lengths) |

The classification of alpha diversity metrics into these four categories provides a systematic framework for selecting appropriate measures for specific research questions [7]. Richness estimators like Chao1 and ACE are particularly valuable when the research question focuses on the presence or absence of taxa, such as in studies investigating the effects of antibiotics on microbial communities [11] [15]. These metrics range from simple counts (observed features) to statistical estimators that account for undetected rare species (Chao1, ACE) [15].

Dominance metrics, including Berger-Parker and Simpson indices, quantify the extent to which a community is dominated by a few abundant taxa [14]. These measures are particularly sensitive to changes in the most abundant community members and can reveal shifts in community structure that might be masked by other metrics. Higher values typically indicate greater dominance, which generally corresponds to lower diversity [14].

Information theory-based metrics like the Shannon index incorporate both the number of taxa and their relative abundances, providing a balanced view of community structure [12]. The Shannon index specifically measures the uncertainty in predicting the identity of a randomly selected individual from the community, with higher values indicating greater diversity [15]. Related metrics like Pielou's evenness specifically isolate the evenness component from the richness component of the Shannon index [12].

Phylogenetic diversity metrics, notably Faith's Phylogenetic Diversity, incorporate evolutionary relationships by summing the branch lengths of the phylogenetic tree spanning all taxa present in a sample [15] [12]. This approach recognizes that a community containing distantly related organisms is more diverse than one containing closely related taxa, even if the raw number of taxa is similar [12].

Essential Alpha Diversity Metrics and Their Calculations

Key Metrics and Their Mathematical Formulations

The selection of appropriate alpha diversity metrics depends on the specific research question and the aspects of community structure most relevant to the study objectives. Based on a comprehensive analysis of frequently used metrics, Cassol et al. (2025) recommend including representatives from each of the four categories to obtain a complete picture of community structure [7]. The following metrics represent a core set that captures the essential dimensions of alpha diversity:

Observed Richness: This is the simplest richness metric, representing the raw count of distinct taxonomic features (e.g., ASVs or OTUs) observed in a sample [15]. The formula is straightforward:

( S{rich} = \sum{s>0} 1_s )

where ( s ) represents each observed taxon [15]. While easily interpretable, this metric is highly sensitive to sampling depth and may underestimate true richness, particularly in communities with many rare species.

Chao1: This non-parametric estimator predicts true species richness by accounting for undetected rare species based on the number of singletons (species represented by a single read) and doubletons (species represented by two reads) [11] [15]. The formula is:

( Chao1 = S{obs} + \frac{F1(F1 - 1)}{2(F2 + 1)} )

where ( S{obs} ) is the number of observed species, ( F1 ) is the number of singletons, and ( F_2 ) is the number of doubletons [15]. Chao1 is particularly useful for datasets with many low-abundance taxa and provides a more accurate estimate of true richness than simple observed counts [15].

Shannon Index: Also known as Shannon entropy or Shannon-Wiener index, this information-theoretic metric incorporates both richness and evenness [15] [12]. It is calculated as:

( H = -\sum{i=1}^{S} pi \ln p_i )

where ( S ) is the total number of species and ( p_i ) is the proportion of the community belonging to species ( i ) [15]. The Shannon index quantifies the uncertainty in predicting the identity of a randomly selected individual from the sample, with higher values indicating greater diversity [12]. Typical values in microbiome studies range from 1 to 3.5, though theoretically it can approach infinity [12].

Berger-Parker Dominance: This straightforward dominance metric represents the proportion of the most abundant species in the community [7] [14]. The formula is:

( dbp = \frac{N1}{N{tot}} )

where ( N1 ) is the abundance of the most dominant species and ( N{tot} ) is the total abundance of all species [14]. Values range from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating greater dominance (and therefore lower evenness) [14]. Its simple interpretation makes it particularly valuable for communicating results to diverse audiences.

Faith's Phylogenetic Diversity: This phylogenetic metric sums the branch lengths of a phylogenetic tree spanning all taxa present in a sample [15] [12]. The calculation is:

( PD = \sumi bi )

where ( b_i ) represents the length of the ( i^{th} ) branch in the tree [15]. This metric captures the evolutionary history represented in a sample, with higher values indicating greater phylogenetic dispersion [12]. It requires a phylogenetic tree as input, typically generated from sequence data prior to diversity analysis.

Comparative Analysis of Alpha Diversity Metrics

Table 2: Characteristics of Common Alpha Diversity Metrics

| Metric | Category | Formula | Sensitive To | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed Features | Richness | ( S{rich} = \sum{s>0} 1_s ) | Number of taxa | Simple, intuitive | Highly sensitive to sampling depth |

| Chao1 | Richness | ( Chao1 = S{obs} + \frac{F1(F1-1)}{2(F2+1)} ) | Rare taxa | Estimates true richness | Requires singletons/doubletons |

| Shannon Index | Information | ( H = -\sum pi \ln pi ) | Richness and evenness | Balanced view of community | Difficult to interpret in isolation |

| Berger-Parker | Dominance | ( dbp = \frac{N1}{N{tot}} ) | Most abundant taxon | Simple biological interpretation | Insensitive to middle-ranked taxa |

| Faith's PD | Phylogenetic | ( PD = \sumi bi ) | Phylogenetic spread | Incorporates evolution | Requires phylogenetic tree |

The table above summarizes the key characteristics, advantages, and limitations of the core alpha diversity metrics. This comparative analysis highlights the importance of selecting multiple metrics that capture different aspects of community structure. For example, while Observed Features and Chao1 both measure richness, Chao1's correction for undetected species makes it more robust for comparing communities with different sampling depths [15]. Similarly, the Shannon index provides a different perspective on community structure than dominance metrics like Berger-Parker, as they respond differently to changes in abundance distribution [7].

Recent research has demonstrated strong correlations between metrics within the same category, suggesting that researchers might avoid redundant metrics from the same category [7]. For instance, in the richness category, Chao1 and ACE show the strongest linear correlation, while in the information category, all metrics derived from Shannon's entropy show strong correlations with each other [7]. This understanding can help researchers select a non-redundant set of metrics that efficiently capture the full spectrum of community characteristics.

Experimental Design and Methodological Considerations

Sample Size and Statistical Power Considerations

Robust experimental design is crucial for obtaining meaningful alpha diversity results. An underpowered study may fail to detect biologically important differences, while an overpowered study wastes resources. Sample size requirements for alpha diversity analyses depend on several factors, including the expected effect size, the specific metric chosen, and the inherent variability of the microbial community [15]. Power analysis conducted by Bujang et al. (2022) revealed that different alpha diversity metrics have varying sensitivity to detect differences between groups, which directly impacts the required sample size [15].

For studies comparing two groups, typical sample sizes range from tens to hundreds of samples per group, with a median of approximately 32 and 24 for case and control groups, respectively, based on a review of 419 microbiome studies [13]. However, these values vary considerably depending on the research question and effect size. Research has shown that beta diversity metrics are generally more sensitive for detecting differences between groups than alpha diversity metrics, but when alpha diversity is the primary outcome, careful power calculations are essential [15]. The same study noted that the structure of the data influences which alpha metrics are most sensitive, further complicating power calculations [15].

To avoid p-hacking (trying multiple metrics until statistically significant results are obtained), researchers should pre-specify their primary alpha diversity metrics in a statistical analysis plan before data collection [15]. This approach maintains statistical integrity and ensures that reported results reflect true biological differences rather than selective reporting. When publishing results, researchers should clearly report the justification for sample size decisions, whether based on preliminary data, power calculations, or practical constraints.

Normalization and Rarefaction Procedures

Microbiome data are inherently compositional and characterized by varying sequencing depths across samples, which can confound diversity measurements if not properly addressed [12]. Normalization techniques aim to remove technical artifacts while preserving biological signals, with rarefaction being the most common method for diversity analyses [12].

Rarefaction involves subsampling without replacement to a predetermined sequencing depth, creating standardized library sizes across samples [12]. The process involves:

- Calculating the total read count for each sample

- Selecting a minimum sequencing depth that retains an acceptable number of samples

- Randomly subsampling each sample to this depth multiple times (typically 10+ iterations)

- Calculating diversity metrics for each rarefied table

- Averaging the results across iterations

The selection of an appropriate rarefaction depth is critical and typically involves examining alpha rarefaction curves, which plot sequencing depth against expected diversity [12]. The optimal depth is where diversity measures plateau, indicating that additional sequencing would not substantially change diversity estimates [12]. As a practical guideline, rarefaction is particularly beneficial when library sizes vary by more than 10-fold; when library sizes are fairly even, rarefaction may be unnecessary [12].

Alternative normalization methods include converting read counts to relative frequencies (proportions) or using more advanced compositional data analysis techniques [16]. However, rarefaction remains the standard method for diversity analyses in many pipelines, including QIIME 2 [12]. The key advantage of rarefaction is that it retains the count nature of the data, allowing for valid diversity comparisons, though it does discard potentially useful data from samples with high sequencing depth.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standardized Analytical Workflow

A typical workflow for alpha diversity analysis involves sequential steps from raw data processing through statistical comparison. The following diagram illustrates this standard pipeline:

Diagram 1: Alpha Diversity Analysis Workflow

The workflow begins with raw sequencing data from 16S rRNA amplicon or shotgun metagenomic sequencing. Quality control steps including filtering, denoising, and removal of chimeric sequences are critical for generating accurate diversity estimates [12]. These steps are typically performed using tools like DADA2 or DEBLUR, which produce amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) [7].

The next stage involves feature table construction, which tabulates the abundance of each ASV across all samples [12]. For phylogenetic diversity metrics, a phylogenetic tree must be constructed, typically using alignment tools like MAFFT and tree-building algorithms like FastTree [12].

Normalization, typically through rarefaction, is then performed to account for differing sequencing depths across samples [12]. The rarefaction depth should be chosen based on alpha rarefaction curves and feature table summaries to balance diversity capture with sample retention [12].

Alpha diversity calculation follows normalization, with metrics selected based on the research questions and community characteristics [7] [14]. Most analysis pipelines calculate multiple metrics simultaneously to provide a comprehensive view of community structure.

Finally, statistical analysis tests for differences between experimental groups or associations with continuous variables. For simple group comparisons, non-parametric tests like Kruskal-Wallis are often used, while linear mixed-effects models can account for repeated measures or random effects like patient ID in longitudinal studies [12].

Implementation in Analysis Pipelines

Several specialized software packages provide streamlined implementations of alpha diversity analysis. QIIME 2 offers a comprehensive pipeline through its diversity core-metrics-phylogenetic function, which calculates multiple alpha and beta diversity metrics simultaneously [12]. The typical command structure is:

This command generates several alpha diversity vectors, including observed features, Faith's PD, Shannon entropy, and evenness [12]. The sampling depth parameter (--p-sampling-depth) is crucial and should be determined from rarefaction curves and feature table summaries [12].

In the R environment, the mia package provides similar functionality through the addAlpha and getAlpha functions [14]. These functions calculate a wide range of alpha diversity indices and can incorporate rarefaction with multiple iterations. A basic implementation looks like:

For statistical comparison between groups in QIIME 2, the alpha-group-significance command performs Kruskal-Wallis tests with pairwise comparisons and FDR correction [12]. For longitudinal data with repeated measures, q2-longitudinal provides linear mixed-effects models that account for within-subject correlations [12].

Table 3: Essential Tools for Alpha Diversity Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application in Alpha Diversity |

|---|---|---|---|

| QIIME 2 | Software Pipeline | End-to-end microbiome analysis | Calculates multiple alpha diversity metrics with phylogenetic support |

| R (mia package) | Statistical Environment | Statistical computing and visualization | Provides comprehensive alpha diversity calculations and statistical testing |

| DADA2/DEBLUR | Bioinformatics Tool | ASV inference from raw sequences | Produces high-resolution feature tables for diversity calculations |

| MAFFT | Alignment Algorithm | Multiple sequence alignment | Generates alignments for phylogenetic tree construction |

| FastTree | Phylogenetic Tool | Phylogenetic tree inference | Creates trees for Faith's PD calculation |

| PICRUSt | Functional Tool | Metagenome prediction | Enables functional diversity correlations with taxonomic diversity |

| Galaxy | Analysis Platform | Web-based bioinformatics | Provides accessible interface for diversity calculations without coding |

The selection of appropriate tools depends on the research context, computational resources, and analytical needs. QIIME 2 offers a user-friendly, comprehensive solution particularly suited for researchers without extensive programming experience [12]. The platform provides interactive visualizations and standardized workflows that enhance reproducibility. In contrast, R with the mia package offers greater flexibility and customization for complex statistical models and integrated visualizations [14].

The choice between ASV inference methods (DADA2 vs. DEBLUR) can impact alpha diversity estimates, particularly for metrics sensitive to rare taxa like Chao1 [7]. DADA2 removes singletons as part of its denoising algorithm, which affects metrics that rely on singleton counts [7]. DEBLUR retains these rare features, making it more appropriate for richness estimators that incorporate singleton information [7].

For studies incorporating phylogenetic diversity, the tree-building approach (e.g., MAFFT for alignment followed by FastTree for tree inference) represents a critical methodological choice that can influence Faith's PD values [12]. The consistency of tree-building parameters across samples is essential for valid comparisons between experimental groups.

Interpretation Guidelines and Current Research Insights

Biological Interpretation of Alpha Diversity Metrics

Interpreting alpha diversity results requires understanding what each metric reveals about community structure and how these patterns relate to biological, clinical, or environmental contexts. Higher richness typically indicates a more complex community with greater functional potential, while higher evenness suggests a more balanced distribution of abundance among taxa [12]. However, the ecological implications of these patterns depend on the specific habitat and research question.

In human gut microbiome studies, reduced alpha diversity (particularly lower richness) has been associated with various disease states, a condition sometimes termed "dysbiosis" [16]. However, the relationship between diversity and health is complex and habitat-dependent—in some body sites or environmental contexts, lower diversity may be the healthy state [16]. Therefore, interpretation should always be grounded in domain-specific knowledge rather than assuming "higher diversity is always better."

When comparing alpha diversity between groups, it is essential to consider the magnitude of difference in addition to statistical significance. Small but statistically significant differences may not be biologically or clinically meaningful. Furthermore, correlation between alpha diversity and continuous variables (e.g., environmental gradients, clinical parameters) should be interpreted with caution, as diversity metrics can respond non-linearly to underlying drivers.

Recent research has highlighted that different alpha diversity metrics can lead to different conclusions about the same dataset, underscoring the importance of reporting multiple metrics and pre-specifying primary outcomes [15]. Cassol et al. (2025) recommend including at least one metric from each of the four categories (richness, dominance, information, and phylogenetic) to capture complementary aspects of community structure [7]. This comprehensive approach provides a more complete picture of how microbial communities differ across experimental conditions or correlate with variables of interest.

Integration with Broader Microbiome Analysis

Alpha diversity represents just one dimension of microbiome analysis and should be interpreted in conjunction with other analytical approaches. Beta diversity measures, which quantify between-sample differences, often provide greater sensitivity for detecting group differences [15]. Similarly, differential abundance testing of specific taxa can identify the particular microorganisms driving diversity patterns.

The field continues to evolve with ongoing debates about optimal normalization approaches, the handling of rare taxa, and the integration of taxonomic with functional profiles [12] [13]. As research questions grow more complex—incorporating longitudinal sampling, multiple body sites, and integrated multi-omics data—analytical methods must advance accordingly [13]. Recent reviews have identified inconsistencies between stated research objectives and actual analytical approaches in a significant portion of microbiome studies, highlighting the need for more rigorous and transparent analytical reporting [13].

Future directions in alpha diversity analysis include the development of effect size measures specific to diversity metrics, standardized reporting guidelines, and improved integration with functional data. As the field moves toward clinical applications, establishing reference ranges for alpha diversity in different body sites and population subgroups will be essential for interpreting results in diagnostic contexts. By adhering to rigorous analytical practices and interpreting results within appropriate biological contexts, researchers can maximize the insights gained from alpha diversity analyses in microbiome research.

In microbiome research, beta diversity is a fundamental concept that quantifies the differences in taxonomic composition between two or more microbial communities [17] [16]. While alpha diversity describes the species richness, evenness, or diversity within a single sample, beta diversity measures operate at the intersection of samples, quantifying the compositional dissimilarity that exists between them [7] [12]. This measure of between-sample diversity is essential for many popular statistical methods in ecology and is widely used for studying the association between environmental variables and microbial composition [16].

The analysis of beta diversity enables researchers to answer critical questions about how microbial communities differ across various conditions, habitats, or time points. For instance, beta diversity can reveal how gut microbiota composition differs between healthy individuals and those with specific diseases, how soil microbial communities vary across environmental gradients, or how microbial populations shift in response to therapeutic interventions [5]. The choice of beta diversity metric significantly influences results and conclusions, as different indices emphasize distinct aspects of community heterogeneity—some focusing on presence/absence of taxa, others incorporating abundance information, and some additionally considering phylogenetic relationships [18].

Core Concepts and Measurement Approaches

Key Beta Diversity Indices

Multiple indices exist for quantifying beta diversity, each with distinct mathematical properties and ecological interpretations. The table below summarizes the most commonly used beta diversity metrics in microbiome research:

Table 1: Key Beta Diversity Metrics and Their Characteristics

| Metric Name | Considers Abundance? | Phylogenetic? | Key Features and Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bray-Curtis | Yes | No | Measures compositional dissimilarity based on abundance data; sensitive to differences in abundant taxa [17] [16] |

| Jaccard | No | No | Incidence-based; considers only presence/absence of taxa [17] [18] |

| UniFrac | Optional (Weighted/Unweighted) | Yes | Incorporates phylogenetic relationships between taxa; unweighted considers presence/absence, weighted includes abundance [17] |

| Aitchison | Yes | No | Euclidean distance on centered log-ratio (CLR) transformed data; accounts for compositionality [17] |

| Hill-Based Indices | Yes, with adjustable sensitivity | Optional | Systematic framework where parameter q determines sensitivity to rare vs. abundant taxa [18] |

Mathematical Foundations

The mathematical formulation of each beta diversity metric determines how it captures different aspects of community heterogeneity:

Bray-Curtis Dissimilarity is calculated as BC = 1 - 2C/(S1+S2), where S1 and S2 are the total number of individuals (or sequences) in samples 1 and 2, and C is the sum of the lesser values for each species found in both communities [16]. This metric ranges from 0 (identical communities) to 1 (completely distinct communities) and is particularly sensitive to changes in the most abundant taxa.

Hill-Based Dissimilarity provides a systematic framework where the diversity order (q) determines the weight given to relative abundances [18]. The general formula for Hill numbers is:

^q^D = (Σ(pi^q))^(1/(1-q)) for q ≠ 1 ^1^D = exp(-Σ(pi·ln(p_i))) for q = 1

These can be decomposed into beta diversity components: ^q^Dβ = ^q^Dγ / ^q^D_α, which represents the effective number of distinct communities [18].

Aitchison Distance involves first applying the centered log-ratio (CLR) transformation to the abundance data: CLR(x) = ln(x_i / g(x)), where g(x) is the geometric mean of all taxa abundances in the sample, then calculating Euclidean distances between the transformed abundance vectors [17]. This approach effectively handles the compositional nature of microbiome data.

Experimental Design and Protocols

Sample Processing and Data Acquisition

The initial steps in beta diversity analysis involve careful sample processing to generate high-quality data suitable for dissimilarity quantification:

Sample Collection: Collect microbial samples (e.g., stool, soil, water) using standardized protocols appropriate for the habitat being studied. Biological replicates are essential for robust statistical analysis [5].

DNA Extraction and Sequencing: Extract genomic DNA using kits designed for the specific sample type. Amplify the 16S rRNA gene (for bacteria) or ITS region (for fungi) using barcoded primers, then sequence on platforms such as Illumina MiSeq or HiSeq [5].

Sequence Processing: Process raw sequences using bioinformatics pipelines such as DADA2 or DEBLUR to infer amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) or cluster into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at a defined similarity threshold (typically 97%) [18] [5]. Remove potential contaminants and chimera sequences.

Taxonomic Assignment: Classify sequences against reference databases such as Greengenes, SILVA, or UNITE using classifiers like RDP, BLAST, or QIIME2's feature-classifier [5].

Beta Diversity Calculation Workflow

Diagram: Beta Diversity Analysis Workflow

The computational workflow for beta diversity analysis involves several critical steps:

Data Normalization: Account for uneven sequencing depth using methods such as:

Distance Matrix Calculation: Compute pairwise dissimilarities between all samples using selected beta diversity metrics. Most computational tools can generate multiple distance matrices simultaneously for comparative analysis.

Statistical Validation: Assess the strength of association between community composition and experimental factors using:

- PERMANOVA: Permutational multivariate analysis of variance tests whether groups of samples are significantly different in composition [17]

- Mantel Test: Correlates distance matrices with environmental variables or other distance matrices

- Dissimilarity-Overlap Analysis (DOA): Examines the relationship between overlap (shared species) and dissimilarity (abundance differences) to infer universality of community dynamics [19]

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Beta Diversity Analysis

| Category | Specific Products/Techniques | Function in Beta Diversity Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | MoBio PowerSoil Kit, DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit | Standardized microbial DNA isolation from various sample types [5] |

| PCR Reagents | HotStart Taq Polymerase, Barcoded 16S/ITS Primers | Amplification of target regions with sample-specific barcodes for multiplexing [5] |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina MiSeq/HiSeq, Ion Torrent PGM | High-throughput amplicon sequencing [18] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | QIIME2, mothur, DADA2, DEBLUR | Processing raw sequences into ASV/OTU tables [18] [12] |

| Statistical Software | R (vegan, phyloseq), Python (scikit-bio, qdiv) | Calculation of diversity metrics and statistical testing [17] [18] |

| Reference Databases | Greengenes, SILVA, UNITE | Taxonomic classification of sequences [5] |

Data Analysis and Visualization

Ordination Techniques for Beta Diversity

Visualization of beta diversity patterns typically employs ordination techniques that project high-dimensional community data into lower-dimensional spaces:

Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA): A non-linear dimension reduction technique particularly suited for visualizing dissimilarity matrices. With Euclidean distances, PCoA is identical to Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [17]. PCoA plots show samples as points in two or three-dimensional space, where proximity indicates similar community composition.

Non-Metric Multidimensional Scaling (NMDS): An ordination method that preserves the rank order of dissimilarities rather than their absolute values, making it robust to non-linear relationships.

The following R code demonstrates a typical PCoA visualization workflow using the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity metric:

Statistical Testing and Interpretation

Quantifying whether observed group differences in beta diversity are statistically significant is crucial for drawing valid biological conclusions:

- PERMANOVA Testing: The following R code demonstrates how to test the association between community composition and experimental factors using PERMANOVA:

This analysis tests the null hypothesis that the centroids and dispersion of groups are equivalent for all groups. A significant p-value (typically < 0.05) indicates that composition differs significantly between groups [17].

- Dissimilarity-Overlap Analysis (DOA): This specialized approach examines the relationship between overlap (O = half of the sum of relative abundances of shared species) and dissimilarity (D = divergence between renormalized abundance profiles of shared species). A negative correlation in the high-overlap region suggests universal microbial dynamics across habitats [19].

Applications in Research and Drug Development

Beta diversity analysis has become an indispensable tool in both basic research and applied drug development contexts:

Clinical Biomarker Discovery: Identifying microbial signatures associated with disease states by comparing beta diversity between patient groups. For example, studies have shown reduced beta diversity in inflammatory bowel disease patients compared to healthy controls.

Therapeutic Monitoring: Tracking how microbial communities respond to interventions such as antibiotics, probiotics, or fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT). For instance, auto-FMT has been shown to restore gut microbial diversity and composition to pre-transplantation states in patients receiving stem cell transplantation [12].

Environmental Assessment: Evaluating how environmental factors, pollutants, or land use changes affect microbial ecosystems. Studies have demonstrated that soils support the highest bacterial richness within a single sample, while sediment assemblages display the highest gamma-diversity [5].

Drug Development: Screening compound libraries for molecules that modulate microbial community structure toward healthier states, particularly in metabolic and inflammatory diseases.

Advanced Methodological Considerations

Normalization Strategies

The compositional nature of microbiome data presents unique challenges for beta diversity analysis. Several normalization approaches address these issues:

Rarefaction: Subsampling without replacement to an even sequencing depth remains a common approach, particularly for diversity analyses [12]. The optimal rarefaction depth is determined using alpha rarefaction curves to identify where diversity estimates stabilize.

Compositional Data Transformations: CLR transformation effectively handles compositionality by normalizing each feature relative to the geometric mean of the sample [17] [16]. This approach preserves more data than rarefaction but converts data to a log-ratio scale.

Alternative Approaches: More recent methods such as ANCOM, ALDEx2, and breakaway implement plugin-specific normalization techniques that may be preferable for certain analytical goals [12].

Comparative Performance of Beta Diversity Metrics

The choice of beta diversity metric should align with specific research questions and data characteristics:

Abundance-Based vs. Incidence-Based: Bray-Curtis and similar abundance-weighted metrics are more sensitive to changes in dominant taxa, while Jaccard and other incidence-based metrics focus solely on presence/absence patterns [18].

Phylogenetic vs. Non-Phylogenetic: UniFrac distances incorporate evolutionary relationships, potentially capturing functional differences more effectively than taxonomy-based measures [17].

Hill-Based Framework: This approach provides a systematic way to explore how sensitivity to rare versus abundant taxa influences results by varying the diversity order parameter q [18].

Diagram: Relationship Between Diversity Metrics and Data Characteristics

Beta diversity analysis provides a powerful framework for quantifying and interpreting differences between microbial communities. The selection of appropriate dissimilarity metrics, normalization strategies, and statistical approaches should be guided by specific research questions and study designs. As microbiome research continues to evolve, beta diversity remains an essential tool for understanding microbial ecology, host-microbe interactions, and the functional implications of community compositional changes. Future methodological advances will likely focus on integrating multi-omics data, improving normalization techniques for sparse compositional data, and developing more powerful statistical frameworks for longitudinal and cross-sectional study designs.

In microbiome research, diversity indices are essential statistical tools for summarizing and comparing the complex composition of microbial communities. These metrics translate high-dimensional taxonomic data into interpretable values that characterize ecological communities, enabling researchers to detect changes and patterns across different environmental conditions or experimental treatments. The analysis of diversity is typically categorized into two complementary approaches: alpha diversity, which measures the diversity within a single sample, and beta diversity, which quantifies the differences in composition between samples [20] [16]. The selection of appropriate metrics is crucial, as different indices reflect distinct aspects of community structure, such as species richness (the number of species), evenness (the uniformity of species abundances), or phylogenetic relationships [7]. This guide provides an in-depth technical overview of the core diversity metrics—Shannon, Simpson, and Bray-Curtis—that are fundamental to robust microbiome analysis, complete with their mathematical foundations, interpretation guidelines, and standard implementation protocols.

Alpha Diversity: Within-Sample Diversity

Alpha diversity metrics summarize the structure of a microbial community from a single sample. They primarily capture two key ecological concepts: richness (the number of distinct taxonomic groups) and evenness (the uniformity in the abundance distribution of these groups) [7] [15]. No single metric provides a complete picture; therefore, a comprehensive analysis often employs multiple metrics to capture different facets of diversity.

Table 1: Key Alpha Diversity Metrics and Their Properties

| Metric Name | Mathematical Formula | Key Features | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shannon Index | ( H = -\sum{i=1}^{S} pi \ln(p_i) ) [21] | Combines richness and evenness [15]. Sensitive to changes in rare species [7]. | Higher values indicate greater diversity and evenness. A value of 0 signifies only one species is present [21]. |

| Shannon Equitability | ( E_H = H / \ln(S) ) [21] | Standardizes the Shannon Index to a 0-1 scale. | Measures pure evenness. A value of 1 indicates perfect evenness [21]. |

| Simpson's Index | ( D = \sum{i=1}^{S} pi^2 ) [22] | Probability that two randomly selected individuals belong to the same species. Weights towards abundant species [22]. | As D increases, diversity decreases. A value of 1 indicates a community with only one species [22]. |

| Gini-Simpson Index | ( 1 - D ) [22] | Probability that two randomly selected individuals belong to different species. | Ranges from 0 to 1. Higher values indicate greater diversity [22]. |

| Inverse Simpson Index | ( 1/D ) [22] | Effective number of abundant species. | A value of 2.99 indicates that the community is as diverse as one with about 3 equally abundant species [22]. |

Shannon Diversity Index

The Shannon Index (or Shannon-Wiener/Shannon-Weaver index) is an information-theoretic measure based on the concept of entropy. It estimates the uncertainty in predicting the taxonomic identity of a randomly chosen individual from the sample [21]. The index is calculated by summing the product of each species' proportion ((p_i)) and the natural logarithm of that proportion across all species [21]. The step-by-step calculation for a hypothetical community with five species is as follows:

Table 2: Worked Example of Shannon Index Calculation

| Species | Count (nᵢ) | Proportion (pᵢ) | ln(pᵢ) | pᵢ * ln(pᵢ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 40 | 0.38 | -0.97 | -0.37 |

| B | 30 | 0.29 | -1.24 | -0.36 |

| C | 20 | 0.19 | -1.66 | -0.32 |

| D | 10 | 0.10 | -2.30 | -0.23 |

| E | 5 | 0.05 | -3.00 | -0.15 |

| Total | 105 | 1.00 | -1.43 |

The Shannon Index ( H ) is the negative sum of the final column: ( H = -(-1.43) = 1.49 ). The Shannon Equitability Index is ( E_H = H / \ln(S) = 1.49 / \ln(5) \approx 0.92 ), indicating high evenness [21].

Simpson's Diversity Index

Simpson's Index emphasizes the dominance of the most abundant species in a community. Unlike the Shannon Index, it is less sensitive to rare species and more influenced by common ones [22]. For a real-world dataset with three species and total population N=1000, the calculation proceeds as follows:

- Calculate N(N-1): ( 1000 \times 999 = 999,000 )

- Calculate nᵢ(nᵢ-1) for each species:

- Species A (300): ( 300 \times 299 = 89,700 )

- Species B (335): ( 335 \times 334 = 111,890 )

- Species C (365): ( 365 \times 364 = 132,860 )

- Sum the nᵢ(nᵢ-1) values: ( 89,700 + 111,890 + 132,860 = 334,450 )

- Calculate Simpson's Index (D): ( D = 334,450 / 999,000 \approx 0.33 )

- Calculate Diversity Indices:

- Gini-Simpson Index (1-D): ( 1 - 0.33 = 0.67 )

- Inverse Simpson Index (1/D): ( 1 / 0.33 \approx 2.99 ) [22]

Beta Diversity: Between-Sample Diversity

While alpha diversity focuses on a single sample, beta diversity quantifies the compositional dissimilarity between two or more samples [16] [17]. It is an essential measure for understanding how microbial communities shift across gradients such as space, time, or environmental conditions. Beta diversity analysis generates a dissimilarity matrix containing the pairwise dissimilarity values for all samples, which serves as the basis for multivariate statistical tests and ordination techniques like Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) [17].

Bray-Curtis Dissimilarity

The Bray-Curtis dissimilarity is one of the most widely used metrics in microbiome studies for comparing community composition. It considers both the presence/absence of taxa and their abundances [16] [17]. The formula for calculating the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity between two samples, j and k, is:

[ BC{jk} = 1 - \frac{2C}{Sj + Sk} = \frac{\sum |x{ij} - x{ik}|}{\sum (x{ij} + x_{ik})} ]

where (x{ij}) and (x{ik}) are the abundances of species i in samples j and k, (Sj) and (Sk) are the total sum of abundances in each sample, and (C) is the sum of the lesser abundances for those species present in both samples. The index ranges from 0 (identical community composition) to 1 (completely dissimilar communities) [17]. It is particularly sensitive to differences in the most abundant species and is considered a robust measure for ecological studies [15].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Implementing a robust diversity analysis requires careful attention to data preprocessing, normalization, and statistical testing. The following workflow outlines the standard procedure from raw data to biological interpretation.

Diagram 1: Microbiome Diversity Analysis Workflow. The standard bioinformatics pipeline for diversity analysis, from raw data processing to alpha and beta diversity assessment.

Protocol: Calculating Beta Diversity and Visualizing with PCoA

This protocol details the steps to calculate beta diversity using the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity and visualize the results using Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA), a common ordination technique. The following R code snippets provide a practical implementation [17].

Step 1: Load Required Libraries and Data

Step 2: Calculate Bray-Curtis Dissimilarity Matrix

Step 3: Perform Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA)

Step 4: Visualize the PCoA Results

Step 5: Statistical Testing with PERMANOVA To quantify whether group differences in community composition are statistically significant, a PERMANOVA test can be performed [17].

Protocol: Calculating Alpha Diversity

This protocol covers the calculation of common alpha diversity metrics, such as Shannon and Simpson indices, from a species abundance table.

Step 1: Prepare the Abundance Table Ensure your data is in a format where rows represent samples and columns represent taxonomic features (e.g., species). The data should be normalized (e.g., converted to relative abundances) before calculation.

Step 2: Calculate Diversity Indices in R

Step 3: Analyze and Compare Groups Once indices are calculated, they can be compared across sample groups using standard statistical tests (e.g., t-test, Wilcoxon test, ANOVA) and visualized via boxplots.

Successful microbiome diversity analysis relies on a combination of laboratory reagents for sample processing and computational tools for data analysis. The following table details key components of the research toolkit.

Table 3: Research Reagent and Computational Solutions for Microbiome Analysis

| Item Name | Type/Category | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA Gene Primers | Wet-lab Reagent | Amplify hypervariable regions of the 16S rRNA gene for taxonomic profiling via amplicon sequencing. |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Wet-lab Reagent | Isolate high-quality microbial genomic DNA from complex sample matrices (e.g., stool, soil, water). |

| Kraken2 | Computational Tool | Assign taxonomic labels to metagenomic sequencing reads using a k-mer based algorithm against a reference database [11]. |

| Bracken | Computational Tool | Estimate species abundance from Kraken2 output using Bayesian reestimation to improve accuracy [11]. |

| QIIME 2 | Computational Platform | End-to-end analysis suite for microbiome data, from raw sequences to diversity analysis and visualization. |

R vegan Package |

Computational Tool | Comprehensive library for ecological analysis, providing functions for calculating diversity indices (diversity), dissimilarity matrices (vegdist), and PERMANOVA (adonis) [17]. |

| CLR Transformation | Data Transformation | Accounts for the compositional nature of microbiome data by normalizing abundances relative to the geometric mean of the sample, often used before applying Euclidean distance [17]. |

| Rarefaction | Normalization Method | Subsampling without replacement to a fixed read count to mitigate the effects of uneven sequencing depth across samples [16]. |

Critical Considerations for Metric Selection and Interpretation

Choosing the right diversity metric is paramount, as this choice can influence the statistical power and biological conclusions of a study [7] [15]. The following diagram and discussion outline the key decision factors.

Diagram 2: Metric Selection and Study Design Strategy. A decision-flow for selecting appropriate diversity metrics based on the research question, emphasizing the importance of a pre-registered analysis plan.

Metric Sensitivity and Study Power: Different metrics have varying sensitivities to biological effects. For instance, beta diversity metrics like Bray-Curtis are often more sensitive for detecting differences between groups than alpha diversity metrics, potentially requiring smaller sample sizes to achieve sufficient statistical power [15]. This sensitivity, however, creates a risk of "p-hacking" if multiple metrics are tested selectively until a significant result is found. To protect against this, it is recommended to publish a statistical analysis plan before conducting experiments [15].

Comprehensive Reporting: Given that a single metric cannot capture all aspects of diversity, reporting a suite of metrics is considered best practice. A comprehensive analysis should include estimates of richness (e.g., observed features), dominance/evenness (e.g., Gini-Simpson, Berger-Parker), phylogenetic diversity (e.g., Faith's PD), and information indices (e.g., Shannon) [7]. This multi-faceted approach ensures that key aspects of community structure are not overlooked.

Data Transformation and Normalization: Microbiome data is inherently compositional, meaning the data sums to a fixed total (e.g., sequencing depth), making relative abundances dependent on each other. Applying transformations like the Center Log-Ratio (CLR) can account for this compositionality [16] [17]. Furthermore, normalization (e.g., rarefaction, scaling) is a critical step to correct for disparities in sequencing depth across samples, which otherwise can skew diversity estimates and lead to spurious conclusions [16].

The Ecological Theory Behind Common Diversity Indices

In microbiome research, diversity indices serve as fundamental statistical tools for quantifying the complexity of microbial communities. These indices transform intricate ecological data into interpretable metrics that describe community structure, stability, and function [23]. The application of these indices spans from assessing environmental impacts on ecosystem health to understanding host-microbe interactions in disease contexts, providing researchers with standardized approaches for comparing communities across different habitats and experimental conditions [24] [25]. Within this framework, diversity is assessed at multiple spatial scales: alpha diversity (within-sample diversity), beta diversity (between-sample diversity), and gamma diversity (overall diversity across multiple samples in a landscape) [24] [25]. This technical guide focuses specifically on the ecological theory and mathematical foundations of the most widely employed diversity indices in contemporary microbiome research, with particular emphasis on their application in alpha diversity assessment.

Theoretical Foundations of Alpha Diversity

Alpha diversity represents the diversity within a specific habitat or ecosystem, quantifying the variety of microbial taxa within individual samples [25]. This concept encompasses two fundamental components: species richness, which refers simply to the number of different species present, and species evenness (or equitability), which describes how equally individuals are distributed among the different species [26] [25] [27]. A community with high alpha diversity typically contains many species (high richness) with relatively equal abundances (high evenness), whereas low alpha diversity may result from dominance by a few species or overall low species counts [27].

The theoretical basis for alpha diversity metrics stems from information theory and probability theory, adapted to ecological contexts [28] [29]. These metrics allow researchers to move beyond simple species counts to more nuanced understandings of community structure, which proves essential when investigating how environmental factors, host characteristics, or therapeutic interventions influence microbial ecosystems [30]. The accurate measurement of alpha diversity provides critical insights into ecosystem functioning, as more diverse communities often exhibit greater functional redundancy, resilience to disturbance, and metabolic versatility [27].

Table 1: Core Components of Alpha Diversity

| Component | Definition | Ecological Interpretation | Supporting Indices |

|---|---|---|---|

| Richness | Number of species present in a sample | Indicates potential functional capacity and niche availability | Chao1, ACE, Observed Species |

| Evenness | Equitability of species abundance distribution | Reflects resource partitioning and competitive dynamics | Pielou's J, Simpson Evenness |

| Diversity | Combined measure of richness and evenness | Represents overall community complexity | Shannon, Simpson |

Mathematical Formulations and Ecological Interpretations

Species Richness Estimators

Chao1 Index

The Chao1 estimator, developed by Chao (1984), predicts total species richness by accounting for undetected rare species based on the abundance of singletons and doubletons in a sample [24] [25]. The formula is expressed as:

$$S{chao1} = S{obs} + \frac{n1(n1-1)}{2(n_2+1)}$$

Where $S{obs}$ is the number of observed species, $n1$ represents singletons (species with only one individual), and $n_2$ represents doubletons (species with exactly two individuals) [24] [25]. Ecologically, Chao1 helps overcome the limitation of undersampling, which is particularly relevant in microbiome studies where rare taxa may remain undetected due to sequencing depth constraints. A higher Chao1 value indicates greater estimated species richness, suggesting more complex ecosystems with numerous niche opportunities [25].

ACE Index

The Abundance-based Coverage Estimator (ACE) provides an alternative approach to richness estimation by classifying species as rare or abundant based on a abundance threshold (typically 10 individuals) [25]. The index is calculated as:

$$S{ace} = S{abund} + \frac{S{rare}}{C{ace}} + \frac{F1}{C{ace}}\gamma^2_{ace}$$

Where $S{abund}$ is the number of abundant species, $S{rare}$ is the number of rare species, $F1$ is the number of singleton species, and $C{ace}$ represents sample coverage [25]. ACE is particularly useful in communities with high unevenness, where a few dominant species coexist with many rare species, a common pattern in microbial communities subjected to selective pressures [25].

Diversity Indices Incorporating Richness and Evenness

Shannon Diversity Index

The Shannon Diversity Index (also called Shannon-Wiener or Shannon-Weaver index) derives from information theory developed by Claude Shannon in 1948 and quantifies the uncertainty in predicting the identity of a randomly selected individual from a community [28] [23] [29]. The index is calculated as:

$$H' = -\sum{i=1}^{S} pi \ln p_i$$

Where $S$ is the total number of species, and $pi$ is the proportion of individuals belonging to species $i$ [23] [27]. The natural logarithm (base e) is typically used, though base 2 is sometimes applied [28]. The Shannon index increases with both the number of species and the equitability of abundance distributions, reaching its maximum value ($H'{max} = \ln S$) when all species are equally abundant [23]. Ecologically, higher Shannon values indicate more complex communities with greater information content, often associated with ecosystem stability and functional redundancy [27]. Recent studies, however, have highlighted that the original Shannon formula demonstrates negative bias at small sample sizes, leading to the development of unbiased estimators like those proposed by Zahl (1977) and Chao et al. (2013) [29].

Simpson Diversity Index

Proposed by Edward Hugh Simpson in 1949, this index quantifies the probability that two randomly selected individuals from a community belong to the same species [23] [25]. The original formulation:

$$D = \sum p_i^2$$

Yields values between 0 and 1, with higher values indicating lower diversity [25]. To align with intuitive understanding (higher values indicating higher diversity), most microbiome researchers use the transformation:

$$S = 1 - D = 1 - \sum p_i^2$$

Or the inverse form:

$$S = \frac{1}{D}$$

The Simpson index places greater weight on dominant species, making it less sensitive to rare species compared to the Shannon index [25] [27]. This property makes it particularly useful for detecting dominance patterns in communities affected by environmental filtering or competitive exclusion [27].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Major Diversity Indices

| Index | Mathematical Formula | Ecological Interpretation | Sensitivity to Rare Species | Typical Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chao1 | $S{chao1} = S{obs} + \frac{n1(n1-1)}{2(n_2+1)}$ | Estimated total species richness | High (specifically addresses undetected rare species) | 1 to total estimated species |

| Shannon | $H' = -\sum{i=1}^{S} pi \ln p_i$ | Uncertainty in species identity | Moderate | 1.5-3.5 (typically in ecological studies) |

| Simpson | $S = 1 - \sum p_i^2$ | Probability two individuals are different species | Low (weights common species) | 0-1 |

| Pielou's J | $J = \frac{H'}{H'_{max}} = \frac{H'}{\ln S}$ | Evenness of species distribution | Moderate (depends on underlying Shannon) | 0-1 |

Experimental Implementation in Microbiome Research

Sample Processing and Data Generation Workflow

The accurate assessment of microbial diversity requires careful experimental design and execution across multiple stages, from sample collection to computational analysis. The following workflow outlines the standard approach in microbiome diversity studies:

From Sequences to Diversity Metrics

Following sequencing, raw data undergoes substantial processing before diversity calculations can be performed. Key steps include:

Sequence Processing: Raw sequences (raw tags) undergo quality control, chimera removal, and filtering to produce effective tags [24]. Current best practices recommend minimum sequencing depths of 30,000-50,000 reads per sample to adequately capture diversity, with lower depths potentially missing rare taxa [24].

OTU/ASV Generation: Traditionally, sequences were clustered into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) based on 97% similarity thresholds [24]. More recently, Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) provide higher resolution by discriminating sequences differing by even single nucleotides, offering improved reproducibility and finer taxonomic resolution [24]. The ASV table serves as the fundamental data structure for all subsequent diversity calculations, with each ASV representing a putative microbial taxon [24].

Diversity Calculations: Using the abundance data from the ASV table, researchers compute various alpha diversity indices. To validate whether sequencing depth adequately captured community diversity, researchers typically employ rarefaction curves, which plot the number of observed species against sequencing effort [24] [31]. When curves approach asymptotes, additional sequencing would unlikely reveal substantial new diversity [31].

Analytical Framework for Diversity Studies

Statistical Comparison of Diversity Metrics

After calculating diversity indices across sample groups, researchers employ statistical tests to determine if observed differences reflect meaningful biological patterns rather than random variation. The choice of statistical approach depends on the number of comparison groups and data distribution properties:

Table 3: Statistical Framework for Alpha Diversity Comparisons

| Number of Groups | Parametric Tests | Non-parametric Tests |

|---|---|---|

| 2 Groups | T-test | Wilcoxon rank-sum test |

| >2 Groups | ANOVA | Kruskal-Wallis test |

Parametric tests assume normally distributed data and homogeneity of variances, while non-parametric tests make no distributional assumptions and are more robust for diversity data that often violates normality assumptions [25] [30]. Significance is typically determined at p < 0.05, with post-hoc pairwise comparisons (e.g., Tukey's test for parametric, Dunn's test for non-parametric) when overall significant differences are detected [30].

Visualization Strategies

Effective visualization is crucial for interpreting and communicating diversity patterns:

Boxplots: Standard displays for comparing alpha diversity distributions across experimental groups, showing median values, interquartile ranges (25th-75th percentiles), and potential outliers [30].

Rarefaction Curves: Plot observed species against sequencing depth to assess sampling adequacy [24] [31].

Rank-Abundance Curves: Display species relative abundance ranked from most to least abundant, with curve width indicating richness and slope reflecting evenness [24] [31].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 4: Essential Research Toolkit for Microbial Diversity Analysis

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Wet Lab Reagents | DNA Extraction Kits (e.g., MoBio PowerSoil) | High-quality microbial DNA extraction |

| PCR Primers (e.g., 16S V4 515F/806R) | Target amplification of phylogenetic marker genes | |

| Sequencing Kits (e.g., Illumina MiSeq) | Library preparation and sequencing | |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines | QIIME/QIIME2 | Comprehensive analysis pipeline from raw sequences to diversity metrics |

| mothur | 16S rRNA analysis pipeline with statistical support | |

| USEARCH/UPARSE | High-speed sequence processing and clustering | |

| R Packages | vegan | Community ecology package with diversity functions |

| phyloseq | Integrated handling of microbiome data | |

| SpadeR | Species richness estimation and diversity analysis |

Methodological Considerations and Limitations

While diversity indices provide valuable ecological insights, researchers must acknowledge several methodological considerations:

Sample Size Sensitivity: Multiple studies have demonstrated that the Shannon index exhibits negative bias at small sample sizes [29]. This has prompted recommendations to use bias-corrected estimators (e.g., Zahl, Chao-Shen) particularly when comparing communities with differing sampling efforts [29].