Beyond Sterility: Investigating the Microbiome in Traditional Sterile Human Sites and Its Implications for Disease and Therapeutics

This article examines the paradigm-shifting controversy surrounding the existence of microbiomes in human sites traditionally considered sterile, such as the placenta, blood, and brain.

Beyond Sterility: Investigating the Microbiome in Traditional Sterile Human Sites and Its Implications for Disease and Therapeutics

Abstract

This article examines the paradigm-shifting controversy surrounding the existence of microbiomes in human sites traditionally considered sterile, such as the placenta, blood, and brain. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational evidence for and against in utero colonization and blood microbiome hypotheses, critically analyzes methodological challenges in low-biomass research, explores the therapeutic potential of pharmacomicrobiomics, and outlines rigorous validation frameworks. By integrating insights from recent studies and expert commentaries, this review aims to equip scientists with a balanced perspective to navigate this contentious yet transformative field, ultimately guiding future research and clinical translation.

Challenging Dogma: The Evidence For and Against Microbiomes in 'Sterile' Sites

For over a century, the prevailing dogma in reproductive biology held that the fetal development environment—encompassing the uterus, placenta, and amniotic fluid—was entirely sterile, with microbial colonization beginning only during passage through the birth canal [1] [2]. This paradigm has been fundamentally challenged by recent technological advances, particularly next-generation sequencing, which have detected microbial DNA in placental tissues, fetal membranes, and even meconium [1] [3]. The ensuing scientific debate between the "sterile womb" and "in utero colonization" hypotheses represents a pivotal controversy in our understanding of human microbiome development and its implications for maternal and infant health [4] [2]. This whitepaper examines the evidentiary basis for both positions, explores methodological challenges, and assesses the implications for future research and therapeutic development.

Historical Paradigm and Contemporary Challenges

The Sterile Womb Paradigm

The traditional view of uterine sterility was rooted in early microbiological techniques that failed to culture microorganisms from placental tissues under non-pathological conditions [1]. This perspective aligned with the immunological understanding of pregnancy as a state requiring tight regulation to prevent rejection of the semi-allogeneic fetus. The placenta was viewed as a sophisticated barrier protecting the fetal compartment from microbial invasion, with contamination occurring only in pathological states such as chorioamnionitis [2]. This paradigm was further supported by the successful establishment of germ-free animal models through cesarean section delivery and maintenance in sterile isolators, demonstrating that mammalian development could proceed without microbial colonization [4] [2].

Challenging the Dogma

The sterile womb paradigm began to erode with early cultural studies that detected bacteria in placental tissues even in the absence of inflammation. Kovalovszki et al. (1982) reported a 16% positivity rate for bacterial culture in human placentas following delivery under non-inflammatory conditions [1]. However, these findings gained limited traction, as conventional cultural methods were known to underestimate microbial presence due to the inability to culture most environmental bacteria ex vivo [1]. The true paradigm shift emerged with applications of molecular techniques, particularly 16S rRNA gene sequencing, which suggested the presence of diverse bacterial communities in placental tissues from healthy pregnancies [1] [3]. A landmark 2014 study by Aagaard et al. described a unique microbiome in the human placenta, characterized primarily by commensal bacteria from the phyla Firmicutes, Tenericutes, Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Fusobacteria [1]. This study proposed that the placental microbiota most closely resembled the oral microbiome, suggesting hematogenous transmission from maternal oral and gut reservoirs [1].

Methodological Considerations and the Contamination Challenge

The central controversy in placental microbiome research stems from profound methodological challenges in studying low-biomass microbial communities, where contamination control becomes paramount.

Technical Limitations and the "Kitome"

The extreme sensitivity of PCR-based methods creates significant challenges for low-biomass samples, as microbial DNA contamination can be introduced at multiple stages: during sample collection, DNA extraction, or from reagents themselves (creating a "kitome") [4] [2]. Bacterial DNA is ubiquitous in laboratory reagents and environments, making it difficult to distinguish true signal from background contamination. Studies with the most rigorous controls have often failed to detect microbial DNA beyond what is present in negative controls [4] [2]. Additionally, the detection of DNA does not necessarily indicate the presence of viable, replicating microorganisms, as DNA can persist from dead cells or environmental contamination [5] [2].

Distinguishing Viable Microorganisms

A critical limitation of DNA-based methods is their inability to differentiate between living and dead microorganisms [5]. This distinction is essential for establishing true colonization rather than mere presence of microbial components. Alternative approaches have been proposed to address this limitation:

- RNA-based methods: Targeting RNA with shorter half-lives (e.g., messenger RNA) rather than ribosomal RNA to identify transcriptionally active microorganisms [5].

- Metaproteomics: Identifying microbial proteins that indicate current metabolic activity [5].

- Metabolomic profiling: Detecting microbial metabolic signatures that confirm functional activity [5].

- Culture techniques: Combining sequencing with cultivation attempts to demonstrate viability, though most bacteria remain unculturable [1] [5].

- Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH): Using microscopy with species-specific probes to visualize intact microorganisms within tissues [4] [2].

Each method has limitations, and a multimodal approach is increasingly recognized as necessary to provide compelling evidence [5].

Experimental Workflows in Placental Microbiome Research

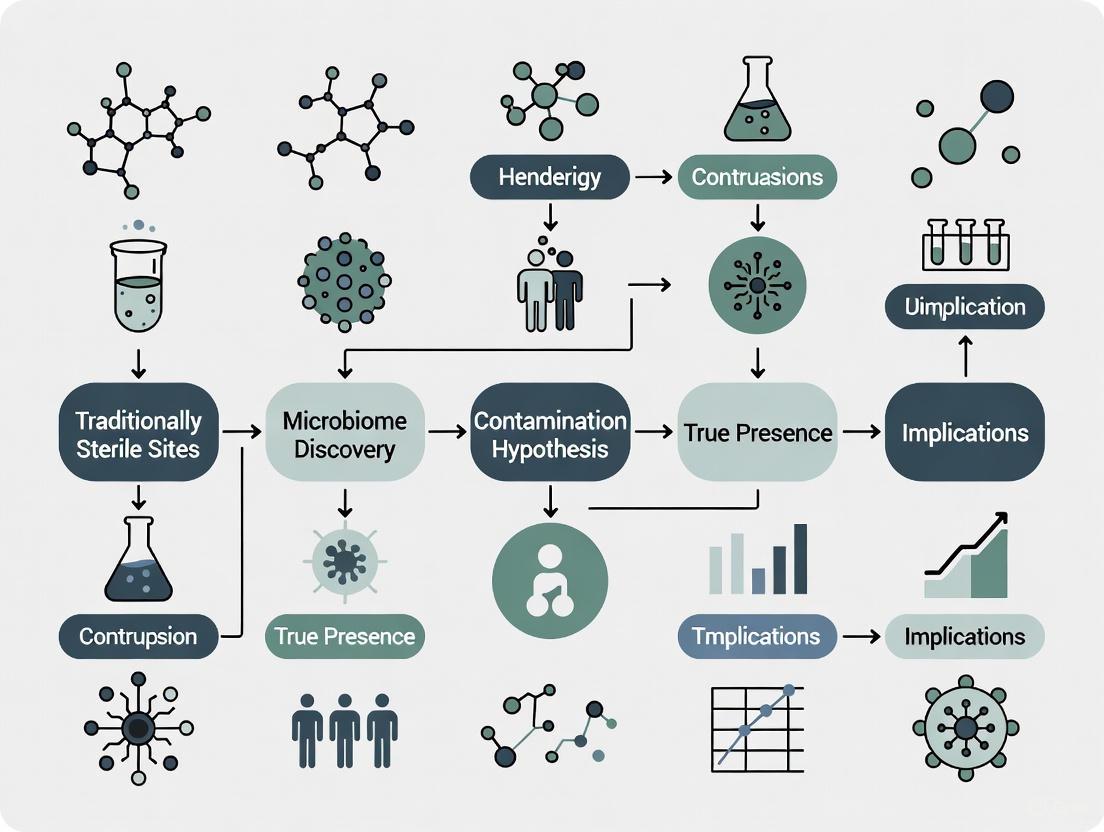

The following diagram illustrates a generalized experimental workflow for placental microbiome research, highlighting critical control points for contamination:

Figure 1. Experimental Workflow for Low-Biomass Microbiome Studies. This diagram outlines key steps in placental microbiome research, highlighting critical points for implementing negative controls, positive controls (spike-ins), and multi-modal verification to address contamination challenges.

Evaluating the Evidence: Philosophical and Biological Perspectives

Philosophical Framework for the Debate

The placental microbiome debate can be understood through Karl Popper's philosophy of science, which emphasizes falsification over verification [2]. According to Popper, confirmations should only count if they result from "risky predictions" that would refute the theory if not observed [2].

The "sterile womb" hypothesis makes the risky prediction that germ-free mammals should be derivable through cesarean delivery and maintenance in sterile environments—a prediction that has been repeatedly verified across multiple species [4] [2]. Conversely, the "in utero colonization" hypothesis would be falsified by the successful establishment of germ-free mammals, as it predicts that at least some microorganisms detected in utero would be viable and capable of colonizing offspring [2].

Most evidence supporting in utero colonization has been verificationist in nature—detecting microbial DNA in fetal tissues—without demonstrating that these signals represent living, reproducing communities essential for development [2]. This approach creates conditions for confirmation bias, where researchers may unconsciously emphasize positive findings while discounting negative results as methodological artifacts [2].

Biological Plausibility and Evolutionary Considerations

From a biological perspective, the existence of a beneficial placental microbiome raises evolutionary questions. If in utero colonization provides advantages for fetal immune development or metabolism, how would such a relationship evolve given the imperative to protect the vulnerable fetal compartment from pathogens? [2]

The sterile womb hypothesis aligns with the observation that mammals have evolved sophisticated barriers to microbial invasion during pregnancy, including specialized immune adaptations at the maternal-fetal interface [4]. The successful derivation of germ-free animals without obvious developmental defects further challenges the necessity of prenatal microbial exposure for normal development [4] [2].

However, proponents of in utero colonization point to potential adaptive benefits, including early immune priming and metabolic programming [1] [6]. The detection of microbial metabolites in fetal tissues, even in the absence of intact microorganisms, suggests possible mechanisms for fetal exposure to microbial influences without direct colonization [2] [7].

Key Studies and Quantitative Findings

Supporting Evidence for Placental Microbiome

Recent clinical and experimental studies have provided quantitative data supporting the existence and potential functional significance of placental microbial communities:

Table 1. Key Studies Reporting Evidence for Placental Microbiome

| Study Reference | Key Findings | Methodology | Potential Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aagaard et al., 2014 [1] | Unique placental microbiome distinct from other body sites; dominated by Firmicutes, Tenericutes, Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Fusobacteria | 16S rRNA sequencing | Contamination concerns in low-biomass samples; inability to confirm viability |

| Recent PTB Study [3] | Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria most dominant phyla in placenta; Ureaplasma urealyticum more abundant in preterm birth placentas | 16S rRNA sequencing | Limited sample size (n=54); potential contamination during delivery |

| Placental-Endocrine Study [7] | Maternal gut Bifidobacterium breve modifies placental endocrine function, nutrient transport, and fetal growth in germ-free mice | Germ-free mouse model, proteomics, metabolomics | Animal model may not fully recapitulate human physiology |

| Vertical Transmission Study [6] | Microbiota detected in placenta, amniotic tissues, and umbilical cord blood; contributes to initial infant gut microbiota | 16S rRNA sequencing, homology analysis | Contamination controls not fully detailed |

Evidence for Sterile Womb Hypothesis

Multiple lines of evidence continue to support the traditional sterile womb paradigm:

Table 2. Key Evidence Supporting Sterile Womb Hypothesis

| Evidence Category | Key Observations | Interpretation | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Germ-free Animal Models | Successful derivation of germ-free mammals through cesarean section maintained in sterile isolators | Demonstrates mammalian development can proceed without microbial colonization | [4] [2] |

| Contamination Concerns | Bacterial DNA detected in negative controls (reagents, kits) at levels similar to test samples | Signals in test samples may represent contamination rather than true biological signal | [4] [2] |

| Inconsistent Detection | Highly variable results across studies; many well-controlled studies find no microbial DNA beyond background | Suggests earlier positive findings may reflect methodological artifacts | [4] [2] |

| Biological Barriers | Sophisticated placental barrier functions and immune adaptations to exclude microbes | Evolutionary investment in protecting fetal compartment from invasion | [4] |

Origins and Potential Functional Significance

Proposed Origins of Placental Microbiota

For those studies reporting placental microbiota, several potential sources have been proposed, with differing evidence supporting each route:

Figure 2. Proposed Origins and Clinical Associations of Placental Microbiota. This diagram illustrates potential transmission routes from maternal sites to the placenta and reported associations with pregnancy outcomes.

Functional Implications for Maternal and Infant Health

Beyond the controversy over existence, research has explored potential functional roles of placental microbiota in pregnancy outcomes and fetal development:

Preterm Birth Association: Several studies report associations between altered placental microbial composition and preterm birth. One recent study found the placental microbiome in preterm births more closely resembled the vaginal microbiome, while in term pregnancies it was more similar to the oral microbiome [3]. Specific taxa including Ureaplasma urealyticum and Treponema maltophilum showed increased abundance in preterm birth samples [3].

Metabolic and Endocrine Regulation: Experimental work in germ-free mice has demonstrated that colonization with specific bacteria (Bifidobacterium breve) can remotely influence placental function, altering the metabolic profile (increased lactate and taurine), upregulating nutrient transporters, and modifying the expression of placental hormones including prolactins and pregnancy-specific glycoproteins [7]. These changes were correlated with improved fetal growth and viability [7].

Fetal Immune Programming: The in utero colonization hypothesis suggests that prenatal microbial exposure may play a role in educating the developing fetal immune system, potentially influencing susceptibility to immune-mediated diseases later in life [1] [6].

Vertical Transmission: Some studies propose that placental microbiota contribute to the initial colonization of the infant gut, forming part of a vertical transmission pathway from mother to offspring [6]. This challenges the traditional view that gut colonization begins primarily during and after birth.

Essential Research Reagents and Methodological Solutions

Research in this controversial field requires specialized reagents and methodologies to address the unique challenges of low-biomass microbiome studies:

Table 3. Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Placental Microbiome Studies

| Reagent/Method Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contamination Controls | DNA extraction kit controls, negative PCR controls, sterile swab controls | Distinguish true signal from background contamination | Must be processed identically to samples; should be included in every experimental batch |

| Positive Controls | Synthetic microbial communities, ZymoBIOMICS standards | Assess detection sensitivity and identify taxonomic biases | Useful for quantifying limit of detection in low-biomass samples |

| Molecular Kits | 16S rRNA sequencing kits, shotgun metagenomics kits, RNA extraction kits | Microbial community profiling and viability assessment | Select kits with minimal bacterial DNA contamination; use same kit lots across experiments |

| Viability Assessment | Propidium monoazide (PMA), RNA sequencing, metaproteomics | Differentiate living from dead microorganisms | PMA pretreatment selectively penetrates dead cells; RNA has shorter half-life than DNA |

| Visualization Reagents | FISH probes, specific antibodies, electron microscopy reagents | Spatial localization of microorganisms in tissues | Provides evidence for tissue integration rather than surface contamination |

| Bioinformatic Tools | Decontam, SourceTracker, Philody | Identify and remove contaminant sequences | Statistical approaches to subtract background signal; requires negative controls |

Future Research Directions and Translational Potential

Despite ongoing controversy, research on placental and in utero microbiota continues to advance with increasingly sophisticated methodologies and applications:

Standardized Protocols: The field requires standardized protocols for sample collection, processing, and analysis specifically validated for low-biomass environments. This includes consensus on negative control implementation, contamination threshold determination, and verification methods [4] [5].

Multi-modal Verification: Future studies should employ complementary methods (DNA, RNA, protein, culture) to provide compelling evidence for viable microbial communities rather than relying on single methodologies [5].

Therapeutic Applications: If specific placental microbial communities are confirmed to beneficially influence pregnancy outcomes, they could represent novel therapeutic targets. Probiotic interventions aimed at modulating placental microbiota have been proposed for preventing preterm birth or fetal growth restriction [1] [7].

Mechanistic Studies: Further research is needed to elucidate mechanisms by which maternal microbiota might remotely influence placental function, potentially through microbial metabolites, immune mediators, or other signaling molecules [7].

The debate between the "sterile womb" and "in utero colonization" hypotheses represents a fundamental controversy in reproductive biology with far-reaching implications for understanding human development and developing novel therapeutic interventions. The current evidence remains divided, with compelling arguments on both sides. Those skeptical of in utero colonization emphasize the methodological challenges of low-biomass microbiome research, the successful derivation of germ-free mammals, and the evolutionary imperative to protect the fetal compartment. Proponents point to detecting microbial DNA in fetal tissues, potential functional impacts on pregnancy outcomes, and experimental evidence that maternal microbiota can remotely influence placental function.

Resolving this controversy will require increasingly sophisticated multidisciplinary approaches that address the profound methodological challenges of studying low-biomass environments. Regardless of the ultimate resolution, this debate has stimulated important refinements in microbiome research methodologies and renewed interest in the prenatal origins of health and disease. The field continues to evolve rapidly, with future studies likely to provide greater clarity on this fundamental question in human biology.

The long-standing dogma that healthy blood is a sterile environment is being fundamentally re-evaluated. For decades, the detection of microorganisms in blood was universally interpreted as a clinical indicator of bloodstream infection. However, advances in sensitive molecular technologies have challenged this paradigm, suggesting the potential existence of a resident blood microbiome in healthy individuals. This concept remains highly controversial within the scientific community, with competing hypotheses about the origin, viability, and biological significance of these microbial signatures. This review synthesizes current evidence from morphological, molecular, and animal studies to evaluate the proposition that blood may host a low-biomass ecosystem of commensal microorganisms, framing this within the broader controversy surrounding microbiomes in traditionally sterile human sites.

The debate centers on whether detected microbial signals represent true colonization or transient contamination. Proponents of the blood microbiome hypothesis point to studies demonstrating bacterial DNA in healthy individuals and visualized microbial structures via electron microscopy [8] [9]. Conversely, large-scale population studies have failed to identify a consistent core community of microbes in human blood, instead supporting a model of sporadic translocation from other body sites [10]. This ongoing controversy mirrors similar debates about sterility in other privileged sites, particularly the prenatal environment [4].

Competing Hypotheses and Theoretical Frameworks

The Blood Microbiome Hypothesis

The blood microbiome hypothesis proposes that blood hosts a low-biomass but consistent community of microorganisms that interact with the host in a commensal or symbiotic relationship. This framework suggests these microbes are not merely contaminants but represent a true ecosystem with potential roles in immune modulation and homeostasis. Key evidence supporting this hypothesis includes:

- Visual Identification: Microscopy studies have documented microbial structures with well-defined cell walls in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) isolated from healthy individuals [9]. These structures demonstrate various proliferation mechanisms, including budding and the formation of electron-dense bodies.

- Culturalbility: Research indicates that blood microbiota from healthy individuals can be resuscitated and cultured under specific conditions, including stress-culturing of lysed whole blood at 43°C in the presence of vitamin K [9].

- Dysbiosis in Disease: Multiple studies have reported alterations in blood microbial profiles associated with disease states. One study in dogs found clear separation between the blood microbiome of healthy subjects and those with chronic gastro-enteropathies, suggesting a potential diagnostic utility [8].

The Transient Translocation Hypothesis

In contrast, the transient translocation hypothesis maintains that blood is fundamentally sterile in healthy states, with detected microbial signals representing temporary incursions from other body sites. This perspective is supported by:

- Large-Scale Sequencing Data: Analysis of blood sequencing data from 9,770 healthy individuals found no evidence for a consistent core microbiome [10]. After rigorous decontamination, no microbial species were detected in 84% of individuals, and the remainder had a median of only one species.

- Sporadic Detection: Microbial species detected in blood demonstrate low prevalence and no co-occurrence patterns, inconsistent with a stable community structure [10].

- Anatomic Origins: Most detected species are commensals associated with the gut (n=40), mouth (n=32), and genitourinary tract (n=18), supporting translocation rather than a resident blood community [10].

Table 1: Key Contrasting Evidence in the Blood Microbiome Debate

| Evidence for Blood Microbiome | Evidence for Transient Translocation |

|---|---|

| Microbial structures visualized via electron microscopy [9] | No species detected in 84% of 9,770 healthy individuals [10] |

| Bacterial DNA differences between healthy and diseased dogs [8] | Low prevalence of detected species (most common in <5% of individuals) [10] |

| Culturalbility under specific conditions [9] | No co-occurrence patterns between different species [10] |

| Distinct profiles compared to fecal microbiome [8] | Most species represent commensals from other body sites [10] |

Methodological Approaches and Technical Challenges

Research into the blood microbiome faces unique methodological challenges due to the extremely low microbial biomass and high host DNA background. Specialized protocols are essential to distinguish true biological signals from contamination.

Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

Rigorous contamination controls must be implemented throughout sample collection and processing:

- Blood Collection: Whole blood should be collected in K3-EDTA tubes via venipuncture after careful disinfection of the skin with chlorhexidine alcohol solution [8]. The disinfection protocol is critical to minimize skin flora contamination.

- DNA Extraction: Different commercial kits are recommended for different sample types. The Exgene Clinic SV kit (GenAll Biotechnology) has been used for blood samples, while the Quick-DNA Fecal/Soil Microbe Miniprep kit (Zymo Research) is suitable for fecal comparisons [8].

- Negative Controls: Both negative and positive controls should be included in the analysis to account for potential contamination introduced during sample processing [8].

Contamination Identification and Filtering

Large datasets with rich batch information enable sophisticated contamination filtering:

- Batch-Specific Contaminants: Laboratory contaminants often show within-batch consistency and between-batch variability, allowing for statistical identification [10].

- Decontamination Filters: Heuristic filters can significantly reduce false positives. One study reduced candidate species from 870 to 117 after decontamination, increasing the proportion of human-associated species from 40% to 78% [10].

- Validation Methods: Confirmation through multiple methods is essential. This includes aligning reads to reference genomes to check coverage breadth and comparing against known contaminant databases [10].

Microscopy Techniques for Morphological Validation

Electron microscopy provides visual evidence complementary to molecular approaches:

- Sample Preparation: Peripheral blood mononuclear cells are isolated from freshly drawn blood and studied both directly and after stress-culturing [9].

- Proliferation Observation: Multiple proliferation mechanisms have been documented, including budding, fission, and a novel "cell within a cell" mechanism [9].

- Structural Diversity: Free circulating microbiota in the PBMC fraction possess well-defined cell walls, while stress-cultured blood microbiota may appear as cell-wall deficient forms [9].

The following diagram illustrates the complex workflow for investigating the low-biomass blood microbiome, highlighting critical control points to address contamination concerns:

Experimental Evidence from Animal and Human Studies

Canine Model of Blood-Gut Microbiome Relationship

A 2023 study investigated the blood microbiome in healthy dogs and those with chronic gastro-enteropathies, providing insights into potential gut-blood communication:

- Experimental Design: Blood and fecal samples were collected from 18 healthy and 19 sick subjects. DNA was extracted, and the V3-V4 regions of the 16S rRNA gene were sequenced on the Illumina platform [8].

- Key Findings: Alpha and beta diversities of both fecal and blood microbiome were significantly different between healthy and sick dogs. Principal coordinates analysis revealed that healthy and sick subjects formed significantly separate clusters for both blood and fecal microbiomes [8].

- Translocation Evidence: The study found shared taxa between gut and blood, suggesting bacterial translocation from the gut to the bloodstream, potentially through a "leaky gut" mechanism or via cellular carriers like dendritic cells [8].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Blood Microbiome Studies

| Reagent/Kit | Specific Application | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Exgene Clinic SV kit (GenAll Biotechnology) | DNA extraction from blood samples | Optimized for low-biomass blood samples, starting from 200μL of blood [8] |

| Quick-DNA Fecal/Soil Microbe Miniprep kit (Zymo Research) | DNA extraction from fecal samples | Efficient extraction from approximately 150mg of fecal material for comparison [8] |

| K3-EDTA tubes | Blood collection | Prevents coagulation while preserving microbial DNA for analysis [8] |

| Chlorhexidine alcohol solution | Skin disinfection | Minimizes contamination from skin flora during venipuncture [8] |

| Vitamin K supplement | Stress-culturing medium | Promotes proliferation of blood microbiota in culture at 43°C [9] |

Human Population Studies

The largest-scale analysis to date examined blood sequencing data from 9,770 healthy individuals across six distinct cohorts:

- Species Identification: After stringent decontamination, 117 microbial species were identified across 8,892 individuals. These spanned 56 genera comprising 110 bacteria, 5 viruses, and 2 fungi [10].

- Replication Signatures: Coverage-based peak-to-trough ratio analyses identified DNA signatures of replicating bacteria in blood, providing culture-independent evidence of potentially viable microorganisms [10].

- Epidemiological Patterns: The most prevalent species, Cutibacterium acnes, was observed in only 4.7% of individuals. No species met the criteria for "core" microbiota, and no co-occurrence patterns between different species were observed [10].

Microscopy Evidence of Microbial Structures

A 2023 microscopy study provided visual evidence of microbial forms in blood from healthy individuals:

- Sample Processing: Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated from freshly drawn blood and stress-cultured lysed whole blood at 43°C with vitamin K [9].

- Morphological Diversity: Free circulating microbiota in the PBMC fraction possessed well-defined cell walls and proliferated by budding or through mechanisms similar to extrusion of progeny bodies [9].

- Proliferation Mechanisms: Stress-cultured blood microbiota proliferated as cell-wall deficient forms, with electron-dense bodies proliferating by fission or producing Gram-negatively stained progeny cells in chains [9].

The following diagram illustrates the proposed mechanisms of microbial translocation from various body sites into the bloodstream, and the potential fates of these microorganisms within the blood ecosystem:

Implications for Drug Development and Therapeutic Innovation

The potential existence of a blood microbiome carries significant implications for pharmaceutical research and diagnostic development:

Diagnostic Applications

Characterization of a blood core microbiome in healthy individuals has potential as a diagnostic tool. The demonstrated separation between blood microbiome profiles of healthy and diseased subjects suggests utility for monitoring disease development and treatment response [8]. Specific applications include:

- Early Detection: Blood microbiome signatures could serve as sensitive biomarkers for early detection of gastrointestinal diseases, inflammatory conditions, and metabolic disorders.

- Treatment Monitoring: Longitudinal monitoring of blood microbiome profiles could provide insights into treatment efficacy and disease progression.

- Companion Diagnostics: Blood microbiome analysis could complement existing diagnostic modalities for chronic conditions characterized by low-grade inflammation.

Therapeutic Considerations

Understanding host-microbe interactions in blood could open new therapeutic avenues:

- Microbiome Modulation: Therapeutic strategies aimed at modifying the blood microbiome could emerge for conditions linked to dysbiosis in this compartment.

- Drug-Microbiome Interactions: The blood microbiome may influence drug metabolism and efficacy, necess consideration in pharmaceutical development.

- Delivery Systems: Knowledge of microbial translocation mechanisms could inform targeted drug delivery approaches across biological barriers.

The question of whether blood represents a sterile environment or hosts a resident microbiome remains unresolved, reflecting broader controversies about microbiomes in traditionally sterile sites. Current evidence presents a complex picture: while large-scale studies fail to identify a consistent core blood microbiome, focused investigations continue to find compelling evidence of microbial presence through multiple detection methodologies.

Future research should prioritize standardized protocols for low-biomass microbiome studies, including rigorous contamination controls and validation through multiple complementary methods. Longitudinal studies tracking individuals from health to disease states will be particularly valuable for understanding the dynamics of blood-associated microbes. Technical advances in single-cell analysis, improved cultivation methods, and more sensitive sequencing technologies may help resolve the current controversies.

The concept of blood as an ecosystem represents a paradigm shift with far-reaching implications for our understanding of human physiology, disease mechanisms, and therapeutic development. Whether this ecosystem represents a true resident community or a dynamic interface for microbial translocation, it undoubtedly merits further investigation as a potential factor in human health and disease.

The long-standing doctrine of the sterile brain, protected by an impenetrable blood-brain barrier (BBB), is undergoing a fundamental reevaluation. The concept of a "brain microbiome" proposes the presence of live bacteria, fungi, and viruses within the healthy brain, challenging core tenets of neuroimmunology and neuroanatomy [11]. This paradigm shift suggests that the brain, much like the gut, may host a community of microorganisms, termed the brain microbiome. The implications of this hypothesis are profound, potentially reshaping our understanding of neurodevelopment, healthy brain function, and the pathogenesis of diverse neurological diseases [12]. However, this field is characterized by intense scientific skepticism and debate, primarily revolving around the critical challenge of distinguishing true microbial colonization from methodological artifacts, such as contamination from other sources or post-mortem invasion [12] [11]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth analysis of the evidence, methodologies, and controversies surrounding the brain microbiome, framed within the broader context of discovering microbiomes in other traditionally sterile human sites.

Examining the Evidence For and Against a Brain Microbiome

The debate is fueled by a growing, yet contested, body of literature reporting microbial presence in both healthy and diseased brains. The key evidence and corresponding counterarguments are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Key Evidence and Controversies in Brain Microbiome Research

| Evidence For a Brain Microbiome | Critical Counterarguments & Sources of Skepticism |

|---|---|

| Genetic Signatures: Bacterial RNA sequences (e.g., from α-Proteobacteria) identified in healthy control brains and HIV/AIDS patients [11]. | Laboratory Contamination: Microbial DNA is ubiquitous in lab environments, reagents, and on surfaces, potentially leading to false-positive signals [12] [11]. |

| Live Culture: 54 bacterial species successfully cultured from multiple regions of lab-raised trout brains, with the lowest load in the olfactory bulb [12]. | Post-mortem Invasion: The BBB breaks down after death, potentially allowing bacteria from the blood or other tissues to enter the brain before sampling [12]. |

| Tracer Studies: Fluorescent bacteria added to fish tanks were later identified within the fish brains, suggesting a pathway for entry [12]. | Blood Vessel Confounding: Brain tissue samples include capillaries; detected microbes may originate from the blood within these vessels, not the brain parenchyma itself [12]. |

| Association with Disease: Higher microbial loads and specific species (e.g., Fusobacterium nucleatum) linked to Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and endometriosis in animal models [12] [13]. | Age as a Confounder: BBB integrity declines with age. Microbial presence in neurodegenerative disease could be a consequence, not a cause, of age-related barrier breakdown [11]. |

| Potential Origin: Some bacteria in human brains (e.g., in Alzheimer's) are species commonly found in the oral microbiome, suggesting a route of entry [11]. | Lack of Consistent Replication: Some well-controlled studies have failed to find microbial signatures in healthy human brains or those from Parkinson's patients, attributing initial signals to contamination [12]. |

A pivotal 2013 study initially investigating HIV/AIDS brains found bacterial RNA in healthy control subjects, first suggesting the brain is not sterile [11]. More recently, a compelling 2024 study on fish has reignited the controversy. Researcher Irene Salinas and her team not only cultured live bacteria from multiple regions of lab-raised trout brains but also demonstrated that bacteria from the environment can translocate into the brain [12]. This finding challenges the assumption that the BBB is an absolute barrier. However, skeptics point to negative studies, such as one that found initial bacterial signals in Parkinson's disease brains were actually due to off-target amplification of human DNA or contamination, highlighting the extreme sensitivity required for this research [12].

Methodological Challenges and Experimental Protocols

The primary hurdle in brain microbiome research is the technically demanding and low-biomass nature of the samples. The following workflow outlines the standard protocol and critical control steps required for a rigorous investigation.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for brain microbiome detection with essential control steps.

As depicted in Diagram 1, the process requires meticulous controls at every stage. Key techniques include:

- 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing: This is the most common method for identifying and classifying bacteria. It involves amplifying and sequencing a specific bacterial gene region [11]. Its main vulnerability is amplifying contaminating DNA present in reagents or lab environments.

- Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing: This technique sequences all the DNA in a sample, allowing for the reconstruction of entire microbial genomes and the identification of non-bacterial organisms [14]. It is more powerful but also more susceptible to noise from host DNA and contaminants.

- Microbial Culture: The successful cultivation of live bacteria from brain tissue, as demonstrated in the fish study, provides some of the most compelling evidence, as it proves viability and is less susceptible to DNA contamination [12].

- Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH): This method uses fluorescent probes to bind to specific microbial RNA or DNA sequences, allowing for the visualization of microbes directly within the tissue context [12].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Brain Microbiome Studies

| Research Tool / Reagent | Primary Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| DNA/RNA Extraction Kits | Isolate nucleic acids from low-biomass brain tissue. | Must include protocols to minimize co-extraction of inhibitors; source kits with low microbial biomass. |

| 16S rRNA Primers | Amplify conserved bacterial gene regions for sequencing. | Choice of primer set influences which bacterial taxa are detected; potential for amplification of contaminants. |

| Bioinformatic Pipelines (e.g., QIIME 2, DADA2) | Process raw sequencing data, remove contaminants, and classify taxa. | Requires dedicated negative control samples for subtraction of contaminating sequences. |

| Cell Culture Media | Attempt to cultivate live bacteria from brain homogenates. | Requires specific media for diverse bacteria; anaerobic conditions often necessary. |

| Fluorescent Probes (for FISH) | Visually localize specific microbes within tissue sections. | Probe design is critical for specificity; signal can be weak in low-biomass samples. |

| Gnotobiotic (Germ-Free) Animals | Model systems to study causal relationships between specific microbes and brain physiology. | Foundational for gut-brain axis research; allows for controlled colonization studies [15] [16]. |

Proposed Mechanisms of Interaction and Signaling Pathways

If microbes do reside in or influence the brain, they likely communicate through multiple, overlapping pathways. The gut-brain axis serves as the primary model for understanding how peripheral microbes can affect the CNS, even if they are not physically present within it. The gut-immune-brain axis is a critical component of this communication.

Diagram 2: Key communication pathways of the gut-immune-brain axis.

The gut-immune-brain axis, illustrated in Diagram 2, demonstrates how gut microbes can influence the brain without physical translocation. Key mechanistic pathways include:

- Immune Signaling: Gut microbes regulate the maturation and function of the immune system. They produce metabolites like short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and influence cytokine production, which can signal to the brain by crossing the BBB or activating neuroimmune cells like microglia [16]. Systemic inflammation is a known contributor to neurodegenerative diseases.

- Vagus Nerve Signaling: This is a direct neural connection between the gut and the brain. Sensory information from the gut is relayed to the brainstem via the vagus nerve [17] [18]. Studies have shown that reduced vagus nerve activity is linked to cognitive deficits in long COVID, and stimulating this nerve can have therapeutic effects [17].

- Microbial Metabolites: Gut bacteria produce neuroactive molecules, including neurotransmitters (e.g., serotonin, dopamine) and metabolites like SCFAs [17] [16]. These can enter the bloodstream, cross the BBB, and directly influence brain function. For instance, gut-produced serotonin has been shown to affect cognitive abilities in mouse models of long COVID [17].

Regarding direct colonization of the brain, several routes have been hypothesized. The olfactory bulb provides a direct connection between the nasal cavity and the brain, bypassing the BBB [12]. A compromised BBB, due to aging or disease, may permit microbial entry from the blood [11]. Some bacteria, such as those from the oral cavity, may exploit peripheral nerve pathways to travel to the brain [11].

Implications for Drug Development and Therapeutic Innovation

The confirmation of a brain microbiome, or even a significant impact from peripheral microbes, would open transformative avenues for neurological drug development.

- Microbiome-Based Biomarkers: Bacterial DNA in the blood is being explored as a potential biomarker to identify vulnerable individuals who could benefit from protective dietary or probiotic interventions [13]. Profiling the gut or potentially the brain microbiome could allow for earlier diagnosis and stratification of patients for neurodegenerative diseases.

- Targeted "Psychobiotics": This class of probiotics is designed to confer mental health benefits by modulating the gut-brain axis [19] [13]. Strains of Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus have shown promise in preclinical models for reducing anxiety and depression-like behaviors and are being tested in humans [19]. For instance, Bifidobacterium longum APC1472 has shown anti-obesity effects in human trials, with unpublished data suggesting it can attenuate hypothalamic molecular alterations in mice [13].

- Prebiotics and Postbiotics: Therapeutics may shift from live bacteria to the compounds they produce. Prebiotics (fibers that feed beneficial bacteria) and postbiotics (beneficial bacterial metabolites or components) offer more stable and controllable therapeutic modalities [13]. The European Food Safety Authority has already authorized health claims for prebiotics like inulin for improving gut health [13].

- Barrier-Strengthening Strategies: Therapies aimed at reinforcing the integrity of the BBB or the gut barrier could prevent the deleterious passage of microbes or inflammatory molecules into the brain [16]. This represents a novel approach to treating neuroinflammatory conditions.

- Bacterial Amyloid Inhibitors: If bacterial proteins (e.g., curli from E. coli) are found to trigger the misfolding of native proteins like alpha-synuclein in Parkinson's, therapies could be developed to target these microbial amyloids, potentially preventing or slowing disease progression [17].

The field of brain microbiome research is nascent and contentious. Future progress hinges on technical advancements and a concerted effort to address skepticism. Key research priorities include:

- Standardization of Controls: The field must adopt and universally report rigorous negative and positive controls to definitively rule out contamination, as exemplified in the fish study which sterilized exteriors and tested all lab materials [12].

- Longitudinal Human Studies: Research must move beyond post-mortem snapshots to include animal and human studies that track microbial presence in the brain across the lifespan, controlling for age and BBB integrity [11].

- Multi-Omics Integration: Combining genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data from both host and microbiome will be essential to move from correlation to mechanism [13].

- Causation Experiments: Using gnotobiotic animals and targeted bacterial introductions to test whether specific microbes can induce physiological or pathological changes in the brain is crucial [15] [16].

In conclusion, the concept of a brain microbiome represents a frontier in neuroscience with the potential to revolutionize our understanding of brain health and disease. While the evidence is mounting, it is balanced by legitimate and serious skepticism regarding methodological rigor. The gut-brain axis serves as a solid foundation, demonstrating that microbes remote from the CNS can exert powerful effects. Whether through direct colonization or remote signaling, the influence of the microbiome on the brain is undeniable. For researchers and drug development professionals, this area offers a high-risk, high-reward landscape. Success will depend on rigorous validation, sophisticated methodologies, and a willingness to challenge one of the last bastions of sterility in the human body. The ongoing controversy is not a weakness but a hallmark of a vibrant and potentially transformative scientific field.

For more than a century, conventional medical science held that internal organs such as the placenta, amniotic fluid, blood, and brain existed in a sterile state, completely free of microorganisms. This paradigm has been fundamentally challenged by advanced detection technologies, particularly next-generation sequencing, which have revealed the potential presence of microbial communities in these traditionally sterile sites [1] [5]. The controversy surrounding these findings represents a critical frontier in microbiome research, with substantial implications for understanding human development, disease pathogenesis, and therapeutic innovation [20].

The core of this scientific debate centers on distinguishing true colonization from methodological artifacts. As Relman notes, "The presence of DNA is quite distinct from 'bacterial colonization' and very different from the presence of a true 'microbiota'" [20]. This distinction is particularly crucial in low-biomass environments where contamination poses a significant challenge to interpretation. This technical guide examines the current evidence, methodological considerations, and research tools essential for investigating these contested anatomical sites within the broader context of the sterile human site controversy.

Placenta: Gateway to Prenatal Microbial Exposure

Evidence and Controversy

The placental microbiome represents one of the most intensively studied yet controversial sites. Traditionally considered sterile, recent studies have detected specific microbial communities in placental tissue, primarily consisting of Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, and Tenericutes [1] [3]. These findings have prompted the "in utero colonization" hypothesis, suggesting that microbial exposure begins before birth [1]. However, this hypothesis faces significant skepticism from experts who point to the existence of germ-free mammals, inconsistencies in microbial detection across studies, and the high potential for contamination in low-biomass samples [20].

The functional implications of placental microbes are similarly debated. Some researchers propose that abnormal placental microbial communities may associate with pregnancy complications including preterm birth, gestational hypertension, fetal growth restriction, and gestational diabetes mellitus [1]. A 2025 study analyzing oral and placental microbiomes found distinct profiles in women who experienced preterm birth compared to term deliveries, with higher abundances of Treponema maltophilum, Bacteroides sp, Mollicutes, Prevotella buccae, and Ureaplasma urealyticum in the preterm group [3]. Conversely, skeptics argue that evidence for a functional, resident placental microbiota remains insufficient [20].

Methodological Considerations

Placental microbiome research requires exceptional methodological rigor due to extremely low microbial biomass. Key considerations include:

- Contamination Controls: Implementation of multiple negative controls during DNA extraction and amplification to identify reagent contamination [3] [20]

- Sample Collection: Utilization of sterile techniques during placental collection, typically through biopsy or swabbing of the maternal and fetal surfaces [1]

- Viability Assessment: Combination of DNA-based methods with RNA, culture, or metabolic activity assays to confirm microbial viability [5]

Table 1: Key Microbial Taxa Reported in Placental Studies

| Phylum | Relative Abundance | Potential Association |

|---|---|---|

| Proteobacteria | Variable (16-40%) | Predominant in some healthy placental studies [1] [3] |

| Firmicutes | Variable (15-35%) | Associated with maternal gut translocation [1] |

| Bacteroidetes | Variable (5-20%) | Increased in some preterm birth studies [3] |

| Actinobacteria | Variable (3-15%) | Common in oral and skin microbiomes [3] |

| Fusobacterium | Low (<5%) | Associated with periodontal disease and preterm birth [1] [3] |

Amniotic Fluid: Prenatal Environment and Neonatal Outcomes

Current Evidence and Clinical Correlations

The amniotic fluid, traditionally considered sterile, has emerged as a site of interest for understanding prenatal microbial exposure and its impact on neonatal outcomes, particularly in preterm infants. A 2025 prospective observational study of 126 very preterm deliveries (<32 weeks) analyzed amniotic fluid bacterial signatures using 16S rRNA gene metabarcoding [21] [22]. While overall diversity and bacterial community composition did not differ significantly across outcomes, specific taxa associations emerged.

The study found that enrichments in the Escherichia-Shigella cluster were associated with poor acute outcomes, while the predominance of Ureaplasma and Enterococcus species correlated with unrestricted acute and longer-term outcomes [22]. These findings suggest that amniotic fluid microbiota patterns at birth might enable early identification of infants at risk for severe complications of prematurity.

Methodological Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for amniotic fluid microbiome analysis as described in recent studies:

Key Findings from Recent Research

Table 2: Amniotic Fluid Microbial Associations with Preterm Outcomes

| Bacterial Taxa | Association with Outcomes | Potential Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Escherichia-Shigella cluster | Poor acute outcomes (LOI, ROP) | Possible pathogenicity in immature hosts [22] |

| Ureaplasma species | Unrestricted acute and longer-term outcomes | May represent commensal colonization [22] |

| Enterococcus species | Unrestricted acute and longer-term outcomes | Uncertain pathogenicity in this context [22] |

| Gardnerella species | BPD disease severity | Previously associated with vaginal microbiota [22] |

Blood: The Circulating Microbiome

Challenging the Sterile Paradigm

The concept of blood sterility has been fundamentally challenged by recent research demonstrating the presence of microbial DNA and, in some cases, viable microorganisms in circulation [23]. While human blood was traditionally considered sterile, emerging evidence suggests the presence of a transient microbiome, which may influence health and disease [24]. At the phylum level, the blood microbiome is predominantly composed of Proteobacteria, with Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, and Firmicutes following in abundance [23].

The origins of blood-associated microbes are believed to be primarily translocation from microbe-rich environments such as the gastrointestinal tract and oral cavity, often triggered by mucosal injury or increased intestinal permeability [23]. A large-scale study reported no consistent core blood microbiome, reinforcing the hypothesis of peripheral origin through translocation rather than a stable endogenous community [23].

Methodological Challenges and Solutions

Blood microbiome research presents unique methodological challenges:

- Low Biomass: Extremely low microbial density requires sensitive detection methods and rigorous contamination controls [24] [23]

- Viability vs. DNA Detection: Distinguishing between living microorganisms and microbial DNA fragments is technically challenging [5]

- Standardization: Lack of standardized protocols across studies contributes to conflicting results [23]

Recommended approaches include:

- Use of multiple control samples (extraction and amplification controls)

- Implementation of chemical contamination signatures (e.g., using Silica database)

- Integration of viability-enrichment methods (e.g., propidium monoazide treatment)

- Application of both DNA and RNA-based analyses [5] [23]

Clinical Implications

Dysbiosis in blood microbiome composition may indicate or contribute to systemic dysregulation, pointing to its potential role in disease etiology [23]. Specific blood microbiome signatures have been associated with:

- Myocardial Infarction: Proteobacteria, Gammaproteobacteria, and Bacilli show potential as diagnostic biomarkers [24]

- HIV Infection: Increased levels of Proteobacteria and decreased levels of Actinobacteria and Firmicutes observed [23]

- Neurological Disorders: Potential involvement in Parkinson's disease pathogenesis via systemic inflammation [17]

Brain and Gut-Brain Axis: Neurological Connections

The Emerging Brain Microbiome Concept

While direct evidence of a brain microbiome remains limited and highly controversial, research has illuminated the critical role of the gut-brain axis in neurological health and disease. The gut and brain maintain constant communication through multiple pathways including the vagus nerve, microbial metabolites, immune signaling, and the enteric nervous system [17].

The gut may serve as the origin point for some brain disorders. Parkinson's disease exemplifies this connection, with gastrointestinal issues such as constipation often preceding motor symptoms by years or decades [17]. Researchers have found that misfolded alpha-synuclein protein, a hallmark of Parkinson's, may originate in the gut and travel to the brain via the vagus nerve [17].

Mechanisms of Gut-Brain Communication

The following diagram illustrates the primary mechanisms of gut-brain axis communication:

Implications for Disease and Therapeutics

Research into the gut-brain axis has revealed several promising therapeutic avenues:

- Long COVID: Cognitive symptoms may result from reduced serotonin levels and impaired vagus nerve signaling, potentially treatable with vagus nerve stimulation [17]

- Parkinson's Disease: Gut-origin hypothesis suggests potential for early intervention targeting gut microbiome [17]

- Mental Health: Microbial metabolites influence mood, sleep, and motivation through dopamine and other neurotransmitter systems [17]

Controversies and Methodological Challenges

The Sterile Womb Debate

The controversy surrounding in utero colonization represents a central conflict in this field. Experts remain divided on the interpretation of existing evidence:

| Evidence for Sterility | Evidence for Colonization |

|---|---|

| Existence of germ-free mammals argues against obligatory colonization [20] | Bacterial DNA detected in placental tissue, amniotic fluid, and fetal tissues [1] [3] |

| Inconsistent results across studies suggest contamination issues [20] | Specific bacterial taxa consistently associated with pregnancy complications [3] |

| Cultivation methods largely fail to recover viable bacteria [20] | Microscopy and FISH techniques visualize bacteria in placental tissues [1] |

Technical Limitations in Low-Biomass Research

Research in low-biomass environments faces significant methodological hurdles:

- Contamination: Reagents, kits, and laboratory environments contribute contaminating DNA that can overwhelm true signals [5] [20]

- Viability Assessment: DNA-based methods cannot distinguish between living microorganisms, dead cells, or free DNA fragments [5]

- Biomass Limitations: Low absolute abundance of microorganisms challenges detection thresholds [5] [20]

Potential solutions include:

- Implementation of rigorous negative controls and contamination tracking [3] [20]

- Use of multiple complementary detection methods (culture, DNA, RNA, metabolites) [5]

- Application of viability-enrichment techniques (e.g., PMA treatment, RNA sequencing) [5]

- Development of improved bioinformatic tools for contaminant identification [20]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methods for Sterile Site Microbiome Research

| Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | TGuide S96 Magnetic Soil/Stool DNA Kit [24] | Efficient DNA extraction from low-biomass samples | Compare efficiency across kit types; include extraction controls |

| PCR Reagents | KOD FX Neo Buffer, dNTPs [24] | Amplification of target gene regions | Optimize cycle numbers to minimize amplification bias |

| 16S rRNA Primers | 338F (ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCA) and 806R (GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT) [24] | Target V3-V4 hypervariable region for bacterial identification | Provides taxonomic resolution at genus/species level |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina MiSeq/NovaSeq [24] [22] | High-throughput sequencing of amplicons | Balance depth with cost; 50,000+ reads/sample often sufficient |

| Bioinformatics Tools | QIIME 2, DADA2, SILVA database [22] | Processing raw sequences, ASV calling, taxonomic assignment | Standardize pipeline parameters for cross-study comparisons |

| Contamination Controls | Blank extraction controls, no-template PCR controls [3] [22] | Identification and removal of contaminant sequences | Essential for low-biomass studies; must be processed identically to samples |

The investigation of microbiomes in traditionally sterile sites represents a dynamic and rapidly evolving field with significant implications for understanding human physiology and disease. Future research directions should prioritize:

Standardized Methodologies: Development and adoption of standardized protocols for sample collection, processing, and analysis to enable meaningful cross-study comparisons [23] [20]

Viability Assessment: Implementation of multi-omics approaches that combine DNA, RNA, protein, and metabolic analyses to distinguish viable microorganisms from non-viable signals [5]

Functional Studies: Movement beyond descriptive characterization to functional investigations of host-microbe interactions in these sites [1] [17]

Therapeutic Translation: Exploration of targeted interventions modulating these microbial communities for therapeutic benefit [1] [17]

The controversy surrounding microbiomes in traditionally sterile sites reflects the natural progression of scientific understanding as new technologies enable novel observations. While compelling evidence suggests these sites may harbor microorganisms under certain conditions, the field requires continued rigorous investigation to distinguish true colonization from methodological artifacts. What remains clear is that the traditional binary concept of "sterile" versus "non-sterile" requires refinement to accommodate a more nuanced understanding of microbial presence, persistence, and functional impact across human anatomical sites.

For over a century, the prevailing dogma in human biology has been the "sterile womb" paradigm, which posits that the fetus develops in a completely sterile intrauterine environment and that initial microbial colonization occurs only during and after birth [25]. This view has been fundamentally challenged in the last decade by the "in utero colonization" hypothesis, which suggests that microbial acquisition begins before birth, potentially influencing fetal immune and metabolic development [26]. This debate has profound implications for understanding the origins of the human microbiome and its role in health and disease, particularly within the broader context of microbiome research in traditionally sterile human sites.

The controversy has intensified with advancing molecular technologies, as next-generation sequencing techniques have enabled detection of microbial signatures in fetal tissues that were previously inaccessible to culture-based methods [27]. However, these findings remain hotly contested due to methodological challenges inherent in studying low-biomass microbial communities. This review critically examines the evidence for both hypotheses, analyzes methodological approaches and their limitations, and explores the implications for future research directions and therapeutic development.

Historical Context and Evolution of the Debate

The Established Paradigm: Sterile Womb

The sterile womb paradigm was established through decades of research employing traditional culture-based methods and microscopy. As early as 1885, Theodor Escherich described meconium as free of viable bacteria, suggesting a sterile fetal environment [25]. Later studies in the 1920s and 1930s found that 62% of meconium samples from healthy pregnancies were negative for bacteria by aerobic and anaerobic culture [25]. This paradigm was further supported by studies of amniotic fluid, which demonstrated sterility during healthy pregnancies, with bacterial presence only detected in cases of pregnancy complications or prolonged labor [25].

The anatomical and immunological basis for the sterile womb paradigm rests on the placental barrier, which protects the fetus from microbial invaders in the maternal bloodstream [25]. Additionally, the ability to reliably derive axenic (germ-free) animals via cesarean sections strongly supports the sterility of the fetal environment in mammals [25] [2]. These germ-free lines, maintained across multiple generations in sterile isolation, would not be possible if there were consistent microbial colonization in utero.

The Emerging Challenge: In Utero Colonization Hypothesis

The sterile womb paradigm began facing significant challenges following a 2014 study by Aagaard and colleagues that used next-generation sequencing to describe a unique microbiome in the human placenta [2]. This ignited an entire research field investigating microbial communities in various fetal environments, including placenta, cord blood, amniotic fluid, and meconium [2].

Subsequent studies reported bacterial DNA in meconium from healthy neonates, with composition that did not differ based on delivery mode (vaginal vs. cesarean section) [26]. This suggested that initial colonization might occur prior to delivery, independently of birth mode. Other research detected bacterial communities in placental tissue and amniotic fluid from healthy pregnancies, proposing that the infant gut may be populated in utero, possibly through fetal consumption of amniotic fluid [26].

Table 1: Key Historical Milestones in the Sterile Womb Debate

| Time Period | Dominant Paradigm | Key Evidence | Methodological Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1885-early 2000s | Sterile Womb | Negative bacterial cultures from meconium and amniotic fluid; Successful derivation of germ-free animals via C-section | Culture-based methods, Microscopy |

| 2014-Present | Challenge to Paradigm | Detection of bacterial DNA in placental tissue, amniotic fluid, and meconium using molecular methods | 16S rRNA sequencing, Shotgun metagenomics, qPCR |

| 2017-Present | Methodological Critique | Recognition of contamination issues in low-biomass samples; Failure of controlled studies to replicate earlier findings | Improved contamination controls, Statistical decontamination approaches |

Critical Assessment of the Evidence

Evidence Supporting the Sterile Womb Paradigm

The sterile womb hypothesis is supported by multiple lines of evidence beyond historical culture-based studies. Most compelling is the consistent success in deriving germ-free mammals through cesarean sections, which has been achieved in rodents, ungulates, swine, and other species [4] [2]. The maintenance of these sterile lines across generations directly contradicts the concept of a consistent in utero microbial transmission, as any resident microbiota would likely be propagated to offspring.

Modern sequencing studies with rigorous contamination controls have largely failed to detect consistent microbial communities in fetal tissues. A critical review published in 2017 argued that evidence for in utero colonization is extremely weak, founded almost entirely on studies that used molecular approaches with insufficient detection limits for low-biomass populations, lacked appropriate controls, and failed to provide evidence of bacterial viability [25] [28]. These methodological concerns have been reinforced by multiple subsequent investigations that implemented stringent controls and found no evidence of placental or fetal microbiota beyond occasional contamination or pathogen exposure [4].

From an anatomical perspective, the placenta contains multiple barrier mechanisms, including physical separation between maternal and fetal circulations, immune cells, and antimicrobial compounds that would prevent bacterial translocation [27]. The species-specific variations in placental structure further complicate extrapolations between animal models and humans.

Evidence Supporting In Utero Colonization

Despite methodological challenges, several lines of evidence continue to support the possibility of in utero microbial exposure. Multiple studies have detected bacterial DNA in meconium from healthy newborns, with profiles that differ from adult microbiota but show consistency across individuals [26]. Some research has found that the meconium microbiome correlates more strongly with the amniotic fluid microbiome than with maternal vaginal or oral communities, suggesting a distinct in utero origin [26].

Advanced molecular techniques beyond 16S sequencing have provided additional support. One study combining 16S rRNA gene sequencing, qPCR, microscopy, and culture methods reported evidence for bacteria in the fetal intestine [2]. While these findings have been challenged, they represent attempts to address concerns about bacterial viability.

Animal studies have demonstrated that prenatal maternal microbial exposures can influence fetal immune development, though this may occur through microbial metabolites or components rather than live bacteria [27]. This suggests that even in the absence of colonization, in utero exposure to microbial products may play a role in fetal programming.

Table 2: Comparison of Key Arguments in the Debate

| Aspect | Sterile Womb Paradigm | In Utero Colonization Hypothesis |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Evidence | Successful derivation of germ-free animals; Negative cultures from fetal tissues; Historical clinical data | Bacterial DNA detection in placental tissue, amniotic fluid, and meconium |

| View on Molecular Data | Contamination-prone in low-biomass samples; DNA detection does not prove viability | Represents legitimate biological signal from authentic microbial communities |

| Interpretation of Positive Cultures | Contamination or clinical infection | Evidence of commensal colonization |

| Placental Function | Effective barrier to microbes | Permeable to selective bacterial transfer |

| Implied Clinical Significance | Microbiome acquisition happens at birth; C-section effects due to lack of vaginal microbes | Microbiome establishment begins before birth; C-section effects potentially due to disrupted in utero communities |

Methodological Considerations and Experimental Protocols

Technical Challenges in Low-Biomass Microbiome Research

The investigation of potential microbiomes in sterile sites represents a classic low-biomass research challenge, where the signal-to-noise ratio is extremely unfavorable. The primary technical issues include:

- Contamination: Microbial DNA contaminants are ubiquitous in laboratory reagents (the "kitome"), collection materials, and the environment [10] [2]. Even minimal contamination can overwhelm authentic signals from low-biomass samples.

- Viability vs. DNA Detection: The detection of bacterial DNA does not demonstrate the presence of live, replicating bacteria [27]. Bacterial translocation from other body sites or contamination can introduce DNA without established colonization.

- Sample Collection: Ensuring completely aseptic sampling during childbirth or surgical procedures is challenging, particularly when passing through non-sterile bodily sites [29].

Essential Methodological Controls and Protocols

Robust experimental design for prenatal microbiome research must include multiple layers of controls and validation:

Sample Collection Protocols

For placental or fetal tissue collection during cesarean sections:

- Perform surgical site preparation with sequential antiseptic solutions (e.g., 70% ethanol followed by 2% povidone-iodine) [29]

- Use sterile surgical drapes to create isolated field

- Collect samples from the first extracted fetus to minimize environmental exposure time

- Include multiple environmental controls sampled throughout the procedure

- Process samples immediately or store at -80°C in sterile containers

For meconium collection:

- Collect immediately after birth using sterile techniques

- Note time between birth and meconium passage, as later samples show increased bacterial detection [25]

- Use sterile collection devices rather than standard diapers

Laboratory Processing and Analysis

DNA extraction and sequencing protocols must include:

- Multiple negative extraction controls (no template) processed alongside samples

- Positive controls with known low-concentration bacterial communities

- Use of DNA-free reagents and consumables

- Technical replicates to assess reproducibility

Bioinformatic analysis should incorporate:

- Rigorous quality filtering and removal of low-complexity sequences

- Statistical identification and removal of contaminant taxa based on negative controls

- Assessment of bacterial viability through approaches like coverage-based peak-to-trough ratio analyses [10]

- Integration with culture-based methods when possible

Research Reagent Solutions for Low-Biomass Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Controls for Prenatal Microbiome Studies

| Reagent/Control Type | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit, MoBio PowerWater Kit | Efficient lysis of difficult-to-lyse bacteria; inhibitor removal | Document and account for kit-specific "kitome" contaminants |

| Library Preparation Kits | Illumina DNA Prep, Nextera XT | Preparation of sequencing libraries with minimal bias | Include extraction-to-sequencing negative controls |

| Negative Controls | Sterile water, Blank swabs, Empty collection tubes | Identification of environmental and reagent contamination | Process identically to samples throughout entire workflow |

| Positive Controls | Defined low-biomass mock communities, Spike-in organisms | Assessment of detection sensitivity and technical variation | Use phylogenetically diverse species not expected in samples |

| Contamination Tracking | Synthetic DNA spike-ins, Unique molecular identifiers | Differentiation of true signal from contamination | Add at appropriate points in workflow to monitor introduction |

Broader Implications and Future Directions

Implications for Microbiome Research in Other Sterile Sites

The sterile womb debate reflects broader challenges in investigating microbiomes in traditionally sterile human sites. Similar controversies have emerged regarding blood, brain, and other internal tissues [10] [30]. A 2023 study of 9,770 healthy individuals found no evidence for a consistent blood microbiome, instead observing sporadic translocation of commensal microbes from other body sites [10]. This parallels the sterile womb debate, highlighting that microbial DNA detection does not necessarily indicate established microbiomes.

The methodological advances developed for prenatal microbiome research—including rigorous contamination controls, statistical decontamination approaches, and integrated viability assessments—provide valuable frameworks for other low-biomass microbiome investigations. These approaches are particularly relevant for clinical microbiome studies aiming to distinguish causative pathogens from contamination or background signal.

Therapeutic and Clinical Implications

The resolution of the sterile womb debate has direct implications for clinical practice and therapeutic development:

- Cesarean Section Practices: If the womb is sterile, C-sections primarily disrupt vertical transmission during birth, supporting approaches like vaginal seeding to restore typical microbial exposure [31]. If in utero colonization occurs, the impact of C-sections may be more complex.

- Early-Life Microbiome Interventions: Understanding the timing of initial colonization is crucial for designing interventions to optimize microbiome development and prevent immune-mediated diseases.

- Antibiotic Use During Pregnancy: The risks and benefits of prenatal antibiotic administration would be reassessed if consistent in utero colonization is demonstrated.

Future Research Directions

Key priorities for future research include:

- Development of more sensitive methods for assessing bacterial viability in low-biomass samples

- Standardization of contamination controls across research laboratories

- Investigation of potential microbial exposure through transfer of microbial metabolites and components rather than live bacteria [27]

- Multi-omics approaches integrating metatranscriptomics, metabolomics, and proteomics to assess functional potential

- Advanced imaging techniques to visualize potential microbial communities in situ

The debate between the sterile womb paradigm and in utero colonization hypothesis remains unresolved, though current evidence increasingly questions the existence of a consistent prenatal microbiome. The controversy highlights fundamental challenges in low-biomass microbiome research and the importance of rigorous methodological controls. Philosophical frameworks for scientific evaluation suggest that evidence for the sterile womb aligns better with strong scientific principles, as it provides prohibitive tests (germ-free animals) and multiple explanatory angles, while in utero colonization research has primarily relied on descriptive verifications susceptible to confirmation bias [2].

Regardless of the ultimate resolution, this debate has driven important methodological advances in microbiome research and heightened awareness of contamination issues. It has also stimulated valuable investigation into the earliest origins of the human microbiome and its role in health development. Future research should focus on standardized methodologies, integrated approaches assessing bacterial viability, and careful consideration of the philosophical principles of scientific evidence to move beyond mere verification and toward genuine hypothesis testing.

Germ-Free Animal Models as Foundational Evidence for Fetal Sterility

The question of whether healthy fetal tissues are sterile represents a fundamental paradigm shift in human microbiome research. The "sterile womb" hypothesis, a long-held tenet of human biology, posits that in a state of healthy pregnancy, the fetus develops in a sterile intrauterine environment, with microbial colonization commencing during and after birth. Germ-free (GF) animal models have become an indispensable experimental system for interrogating this concept, providing causal evidence distinct from the correlative data of human studies. Within the context of modern research on microbiomes in traditionally sterile sites, these models help disentangle the complex question of whether microbes detected in fetal tissues are resident communities or the result of contamination. This whitepaper details how GF models are derived, maintained, and applied to provide foundational evidence for fetal sterility, serving as a critical technical resource for researchers and drug development professionals navigating this controversial field.

The Theoretical Basis: Germ-Free Animals as a Model System

Conceptual Framework and Definitions

A germ-free (axenic) animal is one reared in sterile isolators and Confirmed to be free of all living microorganisms, including bacteria, viruses, fungi, and archaea [32]. The ability to sustain such metaorganisms demonstrates that a resident microbiota is not an absolute requirement for mammalian life, though it is essential for complete physiological function. GF animals provide a controlled baseline of "zero microbiota" against which the effects of microbial exposure can be measured.

The theoretical strength of using GF models to investigate fetal sterility lies in a straightforward logic: if a fetus were not sterile and instead received a consistent, in-utero microbial inoculum, then GF animals could not exist. The successful derivation and maintenance of GF animals across generations implies that any microbial transmission from mother to fetus is either non-existent or is not an obligate, resilient colonization that cannot be interrupted by sterile hysterectomy and isolation techniques.

The "Germ-Free Syndrome" and Its Implications