Bridging the Translational Gap: Establishing Causality Between Animal Models and Human Studies in Microbiome Research

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical relationship between animal model findings and human studies in microbiome research.

Bridging the Translational Gap: Establishing Causality Between Animal Models and Human Studies in Microbiome Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical relationship between animal model findings and human studies in microbiome research. It explores the foundational principles of host-microbiome interactions, details the application and limitations of current experimental methodologies like germ-free and humanized microbiota mouse models, and addresses pervasive challenges such as establishing causality and overcoming translational bottlenecks. Furthermore, it synthesizes advanced strategies for validating and comparing findings across studies, including the use of machine learning and multi-omics integration. The content is framed by the latest consensus statements and pipeline analyses, offering a practical guide to navigating the complexities of translating preclinical microbiome insights into successful clinical therapies.

The Bedrock of Microbiome Research: From Dysbiosis to Therapeutic Hypotheses

The fundamental challenge in defining dysbiosis stems from the inherent complexity and individuality of the microbiome. Unlike traditional pathogens, dysbiosis represents an ecological imbalance within the microbial community, rather than the presence of a single causative agent [1] [2]. This imbalance can manifest as a reduction in microbial diversity, a loss of beneficial microorganisms, an overgrowth of potentially harmful ones, or a disruption in the community's functional capacity [1] [2]. The core scientific hurdle is the lack of a single, idealized "healthy" microbiome composition against which to compare potentially dysbiotic states [3]. Research indicates that microbiome communities are highly individualized, show a high degree of interindividual variation to perturbation, and tend to be stable over years in healthy adults [3]. Consequently, dysbiosis is often context-specific, with patterns of alteration varying significantly across different diseases and even among individuals with the same condition [3] [2].

Establishing a universal baseline is further complicated by the dynamic nature of the microbiome throughout life. The microbiome undergoes significant development during early life, influenced by factors such as mode of delivery, infant feeding practices, and early antibiotic exposure [3]. This assembly process is shaped by both deterministic host and environmental factors and unpredictable stochastic ecological processes [3]. In adulthood, while the gut microbiome becomes relatively stable, it remains shaped more by environment than host genetics, with factors like diet, medication, and lifestyle accounting for approximately 20% of its variation [3]. The remaining high degree of interindividual variation suggests that a single "healthy" microbiome profile may not exist, but rather a range of functional healthy states [3].

Comparative Analysis: Human Studies vs. Animal Models of Dysbiosis

To understand dysbiosis, researchers employ both human association studies and causal animal models, each with distinct strengths and limitations. The table below summarizes the core methodological approaches and their translational challenges.

Table 1: Comparison of Dysbiosis Research Approaches

| Research Approach | Key Features | Primary Findings on Dysbiosis | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Observational Studies | - Correlates microbiome composition with health status.- Uses sequencing & metabolomic profiling.- Large, diverse cohorts. | - High inter-individual variation [3].- Altered composition in diseases (e.g., IBD, obesity) [1] [2].- Mechanistic links are correlations, not causations [3]. | - Cannot establish causality [3].- Confounded by environment, diet, medications [3]. |

| Human Microbiota-Associated (HMA) Mouse Models | - Transplant human microbiota into germ-free or antibiotic-treated mice [4].- Allows controlled intervention studies. | - Can transfer donor microbial signatures and some disease phenotypes [4].- Demonstrates causal role of microbiota in some conditions (e.g., metabolic syndrome) [4]. | - Host genetics, GI anatomy differ from humans [4].- Risk of overestimating causal associations [4]. |

A recurring theme across both human and animal studies is the association between higher microbial diversity and health, while a dynamic loss of diversity may be prognostic of increased disease risk [3]. However, the specific changes associated with disease are often inconsistent across studies. For instance, in aging research, mouse models have helped isolate age-related changes from environmental confounders, revealing consistent declines in taxa like Lactobacillus and increased abundance of genera like Coprococcus and Turicibacter in aged mice [5]. These models demonstrate that the microbiome contributes significantly to the age-related metabolome, particularly in lipid-associated pathways such as linoleic acid metabolism [5].

Experimental Workflows and Key Signaling Pathways

Establishing HMA Animal Models

A critical methodology for establishing causality in dysbiosis research is the creation of HMA animals. The workflow involves stringent donor screening, standardized sample processing, and careful recipient preparation.

Table 2: Key Protocols for Human Microbiota-Associated (HMA) Model Generation

| Experimental Stage | Standardized Protocol | Rationale & Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Donor Screening | - No antibiotics for 2-12 months [4].- No laxatives for ≥3 months [4].- Exclude GI, neuropsychiatric, and chronic diseases [4]. | Ensures a "healthy" or defined-disease microbiota without recent pharmacological perturbations. |

| Fecal Sample Processing | - Process quickly in anaerobic conditions [4].- Use cryoprotectants for low-temperature storage [4]. | Maintains viability of oxygen-sensitive commensal bacteria during transplantation. |

| Recipient Preparation | - Use germ-free (GF) or antibiotic-induced "pseudo-germ-free" mice [4]. | Creates a vacant niche to maximize engraftment of the human donor microbiota. |

| Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) | - Multiple gavages over single dose [4]. | Significantly improves the efficiency and stability of donor microbiota colonization. |

| Engraftment Validation | - 16S rRNA gene sequencing of recipient fecal samples [4]. | Confirms successful colonization by donor microbiota before beginning experiments. |

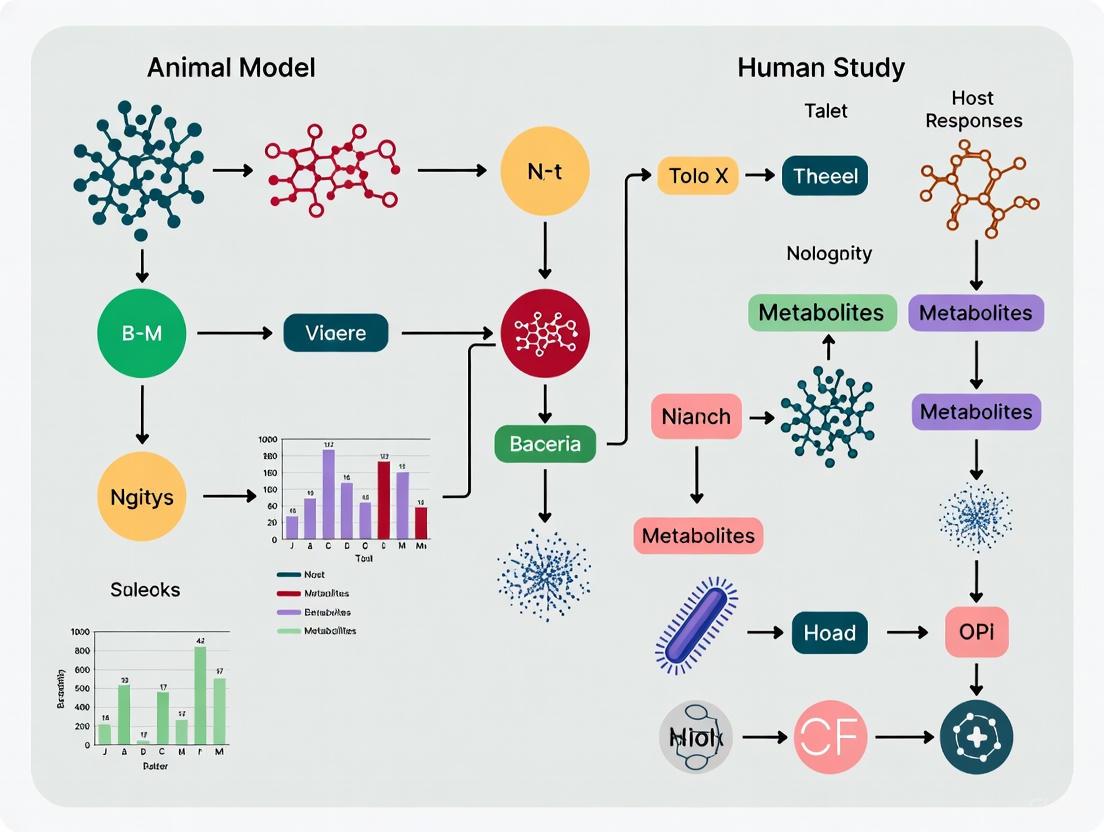

Figure 1: Workflow for Creating HMA Mouse Models. This diagram outlines the standardized protocol for generating HMA animals, from donor screening to final validation.

Pathophysiological Pathways of Dysbiosis

Dysbiosis influences host health through multiple interconnected mechanistic pathways. The primary mechanisms include impaired intestinal barrier function, immune dysregulation, and systemic metabolic effects.

Figure 2: Key Pathophysiological Pathways of Dysbiosis. This diagram illustrates how gut dysbiosis triggers core pathological mechanisms that lead to systemic diseases.

The impaired intestinal barrier allows bacterial products like lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to translocate into circulation, a state known as endotoxemia, which can trigger systemic inflammation [2] [6]. Immune dysregulation occurs as the balance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory responses shifts, often involving Th cell activation and the release of cytokines like IL-1β and TNF-α [6]. Metabolically, dysbiosis alters the production of microbial metabolites, including short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), bile acids, and amino acids, which play critical roles in host metabolism, immune function, and even brain health [7] [5]. These mechanisms form the basis of the gut-brain and gut-liver axes, linking dysbiosis to a wide range of conditions far beyond the gastrointestinal tract [1] [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Cut-edge dysbiosis research relies on a suite of specialized reagents and technological solutions. The following table details key materials and their applications in microbiome research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Microbiome Research

| Research Reagent / Solution | Function & Application | Experimental Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| DNA/RNA Shield Kits | Preserves nucleic acid integrity in fecal samples during collection and storage. | Critical for accurate sequencing data; prevents microbial community shifts post-collection. |

| 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing Primers | Amplifies specific hypervariable regions for taxonomic profiling of bacterial communities. | Choice of primer set (e.g., V4 vs. V3-V4) influences taxonomic resolution and coverage. |

| Shotgun Metagenomics Kits | Enables comprehensive analysis of all genetic material, providing functional and taxonomic insights. | More expensive than 16S sequencing but allows strain-level and functional potential analysis. |

| Anaerobic Chamber Systems | Creates an oxygen-free environment for processing fecal samples and cultivating fastidious gut anaerobes. | Essential for maintaining the viability of oxygen-sensitive commensals for FMT and culture. |

| Targeted Metabolomics Panels | Quantifies specific classes of microbial metabolites (e.g., SCFAs, bile acids, tryptophan metabolites). | Provides functional readout of microbiome activity; links microbial taxa to host-physiological effects. |

| Germ-Free (Axenic) Mice | Serves as recipients for HMA studies, providing a vacant niche for human microbiota engraftment. | Gold-standard but costly; requires specialized isolator facilities for housing and breeding. |

| Antibiotic Cocktails | Used to deplete the indigenous microbiota, creating "pseudo-germ-free" mouse models. | A more accessible alternative to germ-free mice; regimen must be validated for efficacy. |

| Machine Learning Algorithms (e.g., LOCATE) | Integrates multi-omics data to predict host condition from microbiome-metabolome interactions. | Moves beyond correlation to identify latent representations predictive of health and disease [7]. |

The challenge of defining dysbiosis underscores a fundamental truth in microbiome science: health is not defined by a single microbial profile but by a community's functional capacity and resilience. While high microbial diversity is generally associated with health, the specific characteristics of a "healthy" microbiome remain elusive, as they are shaped by a complex interplay of host genetics, life stage, diet, and environmental exposures [3] [8]. The field is moving beyond simple taxonomic associations toward a functional understanding, leveraging multi-omics technologies and machine learning to decipher the complex interactions between microbes, their metabolites, and the host [7] [6]. Tools like LOCATE demonstrate that a latent representation of the microbiome-metabolome interaction can predict host condition more accurately than either dataset alone, offering a promising path forward [7].

Future research must focus on standardizing methodologies, as called for by the STORMS initiative, to improve reproducibility and cross-study comparisons [9]. Furthermore, establishing a universal healthy baseline may be less critical than understanding the ecological rules that govern microbiome stability and function. The integration of artificial intelligence with large-scale, longitudinal studies that capture the dynamic nature of the microbiome across diverse populations will be key to unraveling the context-dependent nature of dysbiosis and developing targeted, personalized microbial therapeutics.

In the realm of scientific research, particularly in the complex field of human microbiome studies, distinguishing between correlation and causation represents a critical intellectual challenge with profound implications for research validity and therapeutic development. Correlation describes a statistical association between variables—when one variable changes, so does the other. Causation, in contrast, means that changes in one variable directly bring about changes in another through a demonstrable cause-and-effect relationship [10]. While causation typically produces correlation, the reverse is not true; correlation does not imply causation [11] [12].

This distinction is especially crucial in microbiome research, where observational studies frequently identify microbial patterns associated with health and disease states. However, determining whether these microbial changes cause disease, result from disease, or merely coincide with disease processes remains methodologically challenging [13] [14]. The consequences of conflating these concepts can be significant, potentially leading to misdirected research resources, flawed therapeutic targets, and ineffective clinical interventions [11] [15]. This review examines the conceptual framework separating correlation from causation, explores experimental approaches for establishing causal relationships in microbiome research, and provides methodological guidance for researchers navigating this critical scientific distinction.

Table: Core Conceptual Differences Between Correlation and Causation

| Aspect | Correlation | Causation |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Statistical association between variables | One variable directly causes changes in another |

| Temporal requirement | None | Cause must precede effect |

| Evidence required | Statistical covariance | Controlled experiments + covariance + elimination of alternatives |

| Implied mechanism | None | Direct mechanistic link |

| Common in | Observational studies | Randomized controlled trials |

The Critical Distinction: Why Correlation Does Not Imply Causation

The maxim "correlation does not imply causation" represents a fundamental principle in scientific reasoning, yet its violation remains commonplace in research interpretation. Two primary problems explain why correlated variables may not be causally related: the third variable problem and the directionality problem [10].

The third variable problem (also known as confounding) occurs when an unaccounted external factor affects both variables being studied, creating a spurious association. A classic example involves ice cream sales and crime rates, which correlate positively but are not causally connected; instead, hot weather influences both variables independently [11] [12]. In microbiome research, numerous confounding variables can create illusory associations, including diet, medications, age, and genetic factors that independently affect both microbial composition and health outcomes [16] [15].

The directionality problem arises when two variables correlate and may indeed have a causal relationship, but determining which variable influences the other proves impossible from the correlation alone. For example, studies have identified correlations between vitamin D levels and depression, but determining whether low vitamin D causes depression or whether depression leads to reduced vitamin D intake remains challenging without experimental manipulation [10]. In microbiome-disease associations, this ambiguity is particularly salient—does microbial dysbiosis cause disease pathology, or does established disease create an environment that favors dysbiosis? [13] [17]

Table: Common Challenges in Establishing Causality in Microbiome Research

| Challenge | Description | Impact on Causal Inference |

|---|---|---|

| Confounding variables | Unmeasured factors (diet, medications, genetics) affecting both microbiome and health | Creates spurious associations between specific microbes and diseases |

| Technical variability | Differences in DNA extraction, sequencing technologies, and bioinformatics across labs [15] | Reduces reproducibility and consistency of microbial signatures |

| Population homogeneity | Over-reliance on white, affluent populations in microbiome studies [15] | Limits generalizability of findings to diverse populations |

| Microbial community complexity | Thousands of interacting microbial species and strains | Difficult to isolate effects of individual microbial taxa |

Establishing Causality: Experimental Approaches in Microbiome Research

Moving from correlational observations to causal conclusions requires specific experimental approaches that can test and verify hypothesized cause-effect relationships. In microbiome research, this typically involves a multi-stage "funnel" approach that progresses from broad associations to increasingly precise mechanistic investigations [13].

The Causal Funnel: From Associations to Molecular Mechanisms

Research to establish microbiome-disease causality often follows a sequential pathway of evidence generation [13]:

- Level 1: Associations - Observational studies identify microorganisms statistically associated with diseased versus healthy individuals using sequencing technologies.

- Level 2: Altered phenotypes in microbiome-depleted models - Studies in germ-free animals or antibiotic-treated organisms demonstrate that microbes play causal roles in disease pathophysiology.

- Level 3: Phenotype transfer via fecal microbiota transplants (FMT) - Transfer of microbial communities from diseased donors to recipient animals establishes whether disease phenotypes can be transmitted through microbiota.

- Level 4: Microbial strain effects - Identification of specific microbial strains that produce disease-associated phenotypes.

- Level 5: Molecular mechanisms - Identification and functional testing of microbially produced molecules that elicit host phenotypes.

This progressive approach enables researchers to narrow candidate causal factors from entire microbial communities to specific strains and eventually to precise molecular mechanisms [13].

Key Experimental Models for Establishing Causality

Different experimental models offer distinct advantages and limitations for establishing causal relationships in microbiome research:

Germ-free animals represent a gold standard model, maintained in completely sterile conditions without any microorganisms. These models allow precise introduction of specific microbial communities or individual strains to test their causal effects on host physiology [13] [17]. However, germ-free animals exhibit physiological abnormalities, including underdeveloped immune systems, which may limit translational relevance [17].

Antibiotic-induced microbiota depletion provides a more accessible alternative to germ-free models, using broad-spectrum antibiotics to substantially reduce endogenous microbial taxa. While more practical and cost-effective, this approach cannot eliminate all intestinal microbes and may have off-target drug effects that complicate interpretation [17].

Human microbiota-associated (HMA) animal models involve transferring fecal microbiota from human donors to germ-free animals, creating "humanized" models that reflect human microbial ecosystems. These models have successfully transferred various human disease phenotypes, including obesity, inflammatory bowel disease, and malnourishment [14] [17].

Microbiome Causality Research Funnel

Methodological Framework: Protocols for Causal Inference

Experimental Workflows for Establishing Causality

Several well-established experimental protocols enable researchers to move from correlation to causation in microbiome studies. These methodologies provide structured approaches to test causal hypotheses and eliminate alternative explanations for observed associations.

Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) protocols involve transferring minimally manipulated microbial communities from donor fecal or cecal matter to recipient animals [17]. Donor inoculum can be prepared fresh or frozen with cryoprotectants, with administration varying from single to multiple gavage cycles. Recipients typically include germ-free mice or conventionally raised mice with antibiotic-induced microbiota depletion. Successful FMT experiments have transferred numerous human disease phenotypes to animal models, providing strong evidence for microbial causality in conditions ranging from metabolic disorders to neurological conditions [13] [17].

Gnotobiotic models involve colonizing germ-free animals with defined microbial communities, ranging from single bacterial strains (monocolonization) to simplified synthetic communities. This approach allows researchers to test the specific effects of individual microbial taxa on host phenotypes while controlling for broader community context [13] [14].

Longitudinal studies track variables over extended time periods, establishing temporal precedence required for causal inference—the cause must precede the effect [12]. In microbiome research, longitudinal sampling can determine whether microbial changes precede disease onset or follow it, helping resolve directionality questions in observed correlations [15].

Causal Inference Experimental Workflow

Causal Inference Methods Beyond Traditional Experimentation

When controlled experiments are not feasible due to ethical, financial, or practical constraints, researchers increasingly turn to advanced causal inference methods from econometrics and machine learning [16]:

Double Machine Learning (Double ML) uses flexible ML models to control for high-dimensional confounders in microbiome-disease associations, providing robust effect estimates even with many potential confounding variables [16].

Instrumental Variables (IV) approaches, including Mendelian randomization, use genetic variants as natural experiments to test causal relationships while minimizing confounding [16] [18].

Difference-in-Differences (DiD) designs compare outcomes over time between groups exposed and unexposed to a putative causal factor, helping isolate causal effects from secular trends [16].

These methodological advances enable more rigorous causal claims from observational data, though they typically require stronger assumptions than randomized experiments.

Table: Comparison of Causal Inference Methodologies

| Method | Key Principle | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized Controlled Trials | Random assignment to treatment/control groups | Gold standard for causal inference; minimizes confounding | Often infeasible for microbiome interventions; ethical constraints |

| Germ-free animal models | Complete absence of microbiota; controlled microbial introduction | Maximum control over microbial variables; establishes causality | Physiological abnormalities; limited translational relevance |

| Double Machine Learning | Uses ML to control for high-dimensional confounders | Handles complex, high-dimensional data; robust to confounding | Requires large sample sizes; complex implementation |

| Mendelian Randomization | Uses genetic variants as instrumental variables | Minimizes confounding; exploits natural variation | Requires specific genetic assumptions; limited to modifiable exposures |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successfully navigating from correlation to causation in microbiome research requires specific experimental tools and reagents. The following table outlines essential materials for conducting causal investigations in microbiome science.

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Microbiome Causal Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Germ-free animals | Provide microbiologically sterile hosts for controlled colonization | Causal testing of specific microbial strains/communities without background microbiota interference |

| Antibiotic cocktails (e.g., ampicillin, vancomycin, neomycin, metronidazole) | Deplete endogenous microbiota in conventional animals | Create microbiota-reduced models for FMT studies; test microbiota-dependent phenotypes |

| Cryoprotectants (e.g., glycerol) | Preserve microbial viability during frozen storage | Maintain complex microbial community structure in frozen FMT inocula |

| Gnotobiotic isolators | Maintain sterile housing conditions for germ-free animals | Prevent microbial contamination during long-term germ-free animal studies |

| Defined microbial communities | Simplified, reproducible microbial consortia | Test specific microbial combinations in gnotobiotic models; reduce complexity of natural communities |

| Organoid/ gut-on-a-chip systems | Replicate human intestinal microenvironment ex vivo | Study host-microbe interactions in human-derived systems with environmental control |

| Multi-omics platforms (genomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics) | Comprehensive molecular profiling | Identify mechanistic pathways linking microbes to host phenotypes |

Establishing causal relationships between the microbiome and human health represents a fundamental challenge with significant implications for therapeutic development and clinical practice. While correlational studies using high-throughput sequencing technologies have identified numerous associations between microbial patterns and disease states, translating these observations into validated causal mechanisms requires rigorous experimental approaches including germ-free models, fecal microbiota transplantation, gnotobiotic systems, and molecular mechanistic studies. The emerging integration of causal inference methods from econometrics and machine learning offers promising approaches for strengthening causal claims, particularly when traditional randomized experiments are not feasible. By systematically applying these methodological frameworks and maintaining distinction between correlational and causal evidence, researchers can advance the field from associative observations to validated mechanistic insights that support targeted therapeutic interventions.

Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) represents a paradigm shift in the treatment of recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection (rCDI) and establishes a foundational model for establishing causality in microbiome research. Unlike correlative studies, FMT provides direct experimental evidence that restoring a healthy gut microbiota can resolve a specific disease state. This review synthesizes clinical efficacy data, elucidates the mechanistic pathways validated through FMT interventions, and details the standardized protocols that have established FMT as both a therapeutic breakthrough and a powerful scientific tool for deconvoluting host-microbiome interactions. The lessons learned from FMT in rCDI provide a rigorous framework for evaluating microbiome-based therapies in other disease contexts.

The human gut microbiome has been correlated with numerous health and disease states, but proving causal relationships remains a central challenge. FMT's success in rCDI provides one of the clearest examples of a causal link between microbial ecology and human disease. Where observational studies can only identify associations, FMT interventions function as definitive experiments that test the hypothesis that microbial dysbiosis is a principal factor in disease pathogenesis. The restoration of a healthy microbial community leads to resolution of rCDI, demonstrating that microbial ecology is not merely a consequence but a driver of disease. This established causal relationship offers a template for investigating other conditions where dysbiosis is implicated, from inflammatory bowel disease to metabolic and neurological disorders.

Clinical Efficacy: Quantitative Data Establishing the Standard

Robust clinical trials and meta-analyses have consistently demonstrated the superior efficacy of FMT over standard antibiotic therapy for rCDI, transforming clinical practice and validating the causal role of dysbiosis.

Comparative Efficacy of FMT vs. Standard Therapies

Table 1: Clinical Efficacy of FMT for Recurrent CDI from Systematic Reviews

| Comparison | Clinical Cure / Resolution Rate | Source Study Details |

|---|---|---|

| FMT (pooled across routes) | 70% to 91% [19] | Systematic review of 7 studies (N=1,030 patients) [19] |

| Vancomycin (standard therapy) | 19% [19] | Direct comparative data from RCTs [19] |

| Fidaxomicin (standard therapy) | 33% [19] | Direct comparative data from RCTs [19] |

| Donor FMT vs. Autologous FMT | 90.9% vs. 62.5% (p=0.042) [19] | Highlights superiority of healthy donor microbiota [19] |

| Single FMT in Immunocompromised | 75.3% (95% CI, 71.7%-78.6%) [20] | Meta-analysis of 44 studies in high-risk patients [20] |

| Consecutive FMT in Immunocompromised | 87.4% (95% CI, 84.8%-89.6%) [20] | Demonstrates efficacy can be enhanced with repeated treatment [20] |

Standardized, FDA-Approved Microbiota-Based Therapeutics

The clinical success of conventional FMT has spurred the development of standardized, quality-controlled products.

- Rebyota (fecal microbiota, live-jslm): A single-dose, rectally administered suspension derived from donor stool. Clinical trials demonstrated a success rate of approximately 70% at 8 weeks, with a sustained clinical response of ~90% at 6 months in initial responders. Each enema contains a diverse community of microorganisms, with a high percentage of Bacteroides (> 1x10^5 CFU/cc) [21].

- Vowst (fecal microbiota spores, live-brpk): An orally administered, FDA-approved product consisting of spore-based microbiota [22].

These products offer a more standardized and scalable approach compared to conventional FMT, though with comparable high efficacy, further validating the principle of microbiota restoration [21] [22].

Elucidating Causal Mechanisms: From Correlation to Pathophysiology

The therapeutic effect of FMT in rCDI is not merely a black box; research has illuminated specific mechanistic pathways that explain its success, providing a model for how to connect microbial shifts to host physiology.

Restoration of Colonization Resistance

A healthy, diverse gut microbiota provides colonization resistance, which prevents C. difficile spores from germinating and proliferating. Antibiotics disrupt this protective ecosystem, creating an opportunity for C. difficile to establish an infection. FMT directly reverses this by re-introducing a complex microbial community that outcompetes the pathogen for nutrients and ecological niches [22].

Modulation of Bile Acid Metabolism

This is one of the most precisely elucidated causal pathways.

- Primary bile acids (e.g., cholic acid, chenodeoxycholic acid) promote the germination of C. difficile spores into vegetative, toxin-producing cells [22].

- Secondary bile acids (e.g., deoxycholate, lithocholate) inhibit C. difficile germination and growth [22].

- A healthy gut microbiota, particularly specific members of the phylum Firmicutes, performs 7-alpha-dehydroxylation, converting primary bile acids to secondary bile acids. rCDI is characterized by a depletion of these key bacteria. FMT restores the microbial consortia necessary for this critical biotransformation, re-establishing an inhibitory environment for C. difficile [22].

Production of Protective Metabolites

- Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs): Beneficial bacteria in a restored microbiome produce SCFAs like butyrate. Butyrate has multiple protective roles: it inhibits C. difficile growth, promotes the conversion of primary to secondary bile acids, and supports immune modulation and intestinal barrier integrity [22].

The following diagram synthesizes these core mechanisms into a unified pathway of how FMT treats rCDI.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Protocols and Reagents for FMT Research

The translational success of FMT relies on rigorous, reproducible protocols for donor screening, material preparation, and administration.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for FMT Studies

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application | Key Considerations & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Donor Screening Panels | Ensures safety of fecal material by excluding pathogens. | Comprehensive serologic and stool testing for viruses (HIV, Hepatitis), bacteria (C. difficile, Salmonella), parasites [23] [24] [22]. |

| Anaerobic Stool Processing Equipment | Maintains viability of oxygen-sensitive commensal bacteria during preparation. | Automated mixing/filtering systems; work performed in anaerobic chambers or biological safety cabinets [23]. |

| Cryopreservation Solutions | Enables long-term storage of prepared FMT material. | Final concentration of 10% glycerol; storage at -80°C [23]. |

| Placebo Materials | Serves as a control in blinded clinical trials. | Isotonic saline is commonly used as an inert placebo for enemas [24]. |

| DNA Extraction Kits | For microbial genomic DNA extraction from stool pre- and post-FMT. | e.g., PowerMax Extraction Kit; enables 16S rRNA gene sequencing and shotgun metagenomics to assess engraftment [23] [25]. |

Detailed Experimental Methodology

The following diagram outlines a standardized workflow for an FMT clinical trial, from donor to data analysis.

FMT's success in rCDI provides an unparalleled evidence-based framework for establishing causality in microbiome research. It demonstrates that a defined intervention (transplantation of healthy microbiota) leads to a specific phenotypic reversal (resolution of infection) through elucidated mechanisms (bile acid metabolism, SCFA production, colonization resistance). This end-to-end validation, from correlation to mechanistic understanding, sets the "gold standard" that research into other microbiome-associated conditions should strive to emulate. Future work will focus on refining standardized products, identifying key therapeutic consortia within the microbiota, and applying this causal framework to more complex, non-infectious diseases linked to the gut-brain axis, metabolism, and immunity.

The human gut microbiome, a complex ecosystem of trillions of microorganisms, plays an indispensable role in maintaining host health by regulating immune homeostasis, supporting metabolic functions, and protecting against pathogens. Dysbiosis—an imbalance in this microbial community—has been increasingly implicated in the pathogenesis of diverse diseases, including metabolic disorders, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and gastrointestinal cancers [26] [27]. The relationship between microbial shifts and disease is not merely correlative; emerging evidence from animal and human studies demonstrates that specific microbial alterations can directly influence disease pathways through metabolic outputs, immune modulation, and host-microbe co-metabolism [28] [29]. This review synthesizes evidence from recent research to objectively compare the microbial and metabolic signatures associated with these conditions, supported by experimental data and the methodologies used to generate them.

Comparative Analysis of Microbial and Metabolic Signatures Across Diseases

The following sections and tables summarize the key microbial shifts and functional consequences observed in metabolic disorders, IBD, and cancer, providing a side-by-side comparison for researchers.

Table 1: Key Microbial Taxa and Functional Shifts in Metabolic Disorders, IBD, and Cancer

| Disease Category | Key Microbial Shifts (Abundance) | Associated Functional & Metabolic Consequences | Supporting Experimental Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Disorders (Obesity, T2D, NAFLD) | ↑ Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes (F/B) ratio [30]↓ Akkermansia muciniphila [30]↓ Bifidobacterium spp. [30]↓ Butyrate producers (Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Roseburia) [30] | Reduced SCFA production [30]Increased intestinal permeability & metabolic endotoxemia [30]Disrupted bile acid metabolism [30]Altered linoleic acid metabolism (aged models) [5] | Human cohort studies [30]Conventional vs. Germ-Free (GF) mice [5]Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) in mice [4] |

| Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) | ↑ Escherichia coli, Klebsiella [27]↑ Ruminococcus gnavus [27]↓ Faecalibacterium prausnitzii [26] [27]↓ Roseburia hominis [27]↓ SCFA producers (Lachnospiraceae, Ruminococcaceae) [27] | Reduced SCFAs (butyrate) [31] [28]Altered tryptophan metabolism & NAD+ biosynthesis [26] [28]Dysregulated sulfur metabolism & bile acid conversion [28]Increased oxidative stress pathways [27] | Human longitudinal IBD cohorts [28]Human Microbiota-Associated (HMA) mouse models [4] [29]Genome-scale metabolic modeling (coralME) [31] |

| Gastrointestinal Cancers (e.g., Colorectal Cancer - CRC) | ↑ Fusobacterium [32] [27]↑ Bacteroides & Prevotella [32]↓ Lactobacillus [32]↓ Faecalibacterium [32] | Production of oncogenic metabolites (e.g., H2S, secondary bile acids) [32]Disrupted lipid & amino acid metabolism [32]Increased inflammation & immune suppression [32] | Human case-control studies [32] [27]Machine learning models on human microbiomes [32] |

Table 2: Key Pathogenic Mechanisms and Microbial Metabolites in GI Diseases

| Mechanism/Metabolite | Role in Disease Pathogenesis | Associated Diseases |

|---|---|---|

| Reduced Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs) | Loss of anti-inflammatory properties, impaired gut barrier integrity, and dysregulated immune cell differentiation [26] [28]. | IBD [31] [28], Metabolic Disorders [30] |

| Altered Tryptophan Metabolism | Depletion of host tryptophan, disruption of NAD+ biosynthesis, and heightened intestinal inflammation [26] [28]. | IBD [26] [28] |

| Bile Acid Dysregulation | Altered primary-to-secondary bile acid ratios promote inflammation and disrupt immune signaling [28] [27]. | IBD [28], Metabolic Disorders [30] |

| Virulence Factors & Pathobionts | Toxins (e.g., ETEC's LT/ST, CPE) compromise intestinal tight junctions, increasing permeability and inflammation [27]. | IBD [27] |

| Shift to Aerotolerance | Inflammation-driven oxidative stress favors pro-inflammatory aerotolerant bacteria over obligate anaerobes [27]. | IBD [27] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies for Microbiome-Disease Research

A critical component of linking microbes to disease is the use of robust and reproducible experimental models. Below are detailed methodologies for key approaches cited in this field.

Establishment of Human Microbiota-Associated (HMA) Mouse Models

HMA models are indispensable for investigating causal relationships between the human microbiome and host physiology [4].

1. Donor Screening and Fecal Sample Collection:

- Donor Criteria: Healthy donors are typically screened for the absence of gastrointestinal disorders, no recent (1-12 months) antibiotic or laxative use, and a balanced omnivorous diet. Donors with neuropsychiatric disorders, excessive alcohol use, or smoking are often excluded [4].

- Sample Processing: Fecal samples are collected anaerobically and processed immediately, or preserved with cryoprotectants at low temperatures to maintain microbial viability. Samples are diluted, homogenized, and filtered under anaerobic conditions to create a standardized fecal suspension [4].

2. Recipient Preparation and Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT):

- Recipient Animals: Germ-free (GF) mice are the gold standard. Alternatively, pseudo-germ-free mice are created by depleting indigenous microbiota with antibiotic cocktails [4].

- Transplantation Protocol: A single gavage of the fecal suspension is often sufficient for colonization, but multiple gavages over a longer duration significantly improve the engraftment efficiency of the donor microbiota [4].

3. Engraftment Validation:

- Microbial community profiling via 16S rRNA gene sequencing is the primary method to confirm that the recipient's microbiome successfully mirrors the donor's profile [4].

Genome-Scale Metabolic Modeling (e.g., coralME tool)

Computational models like coralME translate genetic data into predictive models of microbial community behavior [31].

- Model Reconstruction: The tool rapidly generates ME-models (models of metabolism, gene, and protein expression) from large omics datasets, linking a microbe's genome to its phenotypic attributes [31].

- Simulation and Prediction: These models can simulate how microbes respond to different nutrients, predict the formation of undesired metabolites (e.g., toxins), and uncover how microbes interact with each other and the host [31].

- Application: For instance, researchers used coralME to generate 495 models of common gut species and simulated the effects of low-iron or low-zinc diets, revealing survival advantages for certain harmful bacteria that traditional models missed [31]. Inputting data from IBD patients allowed the models to reveal real-time microbial activities, such as decreased production of protective short-chain fatty acids and shifts in gut pH [31].

Machine Learning for Cross-Disease Biomarker Prediction

Advanced computational methods are used to identify and validate microbial and metabolic biomarkers across different gastrointestinal diseases (GIDs) [32].

- Data Preprocessing: Sparse features are removed from microbiome and metabolome datasets. The remaining data is normalized (e.g., min-max scaling) to ensure all features contribute equally to the model [32].

- Model Training and Feature Selection: Multiple algorithms, including Random Forest, XGBoost, and LASSO regression, are trained on datasets from specific diseases (e.g., Gastric Cancer (GC), IBD, CRC). These models identify the most significant microbial and metabolite features that distinguish diseased from healthy states [32].

- Cross-Disease Prediction: Models trained on one disease's biomarkers are used to predict another. For example, a model trained on GC data has successfully predicted IBD biomarkers, and a CRC model has predicted GC biomarkers, highlighting shared pathogenic mechanisms across GIDs [32].

Visualization of Key Pathways and Workflows

Tryptophan-NAD+ Pathway Disruption in IBD

The following diagram illustrates the host-microbiome metabolic disruption in tryptophan and NAD+ metabolism, a key pathway identified in IBD studies [28].

Host-Microbiome Metabolic Disruption in IBD. This diagram illustrates how inflammation in IBD drives host tryptophan depletion via the kynurenine pathway, impairing NAD+ biosynthesis. Concurrently, the microbiome shows reduced production of nicotinic acid, a key NAD+ precursor, exacerbating the metabolic deficit [28].

Workflow for Human Microbiota-Associated (HMA) Model Generation

This flowchart outlines the general procedure for creating HMA mouse models, a cornerstone of causal microbiome research [4].

HMA Mouse Model Generation Workflow. The process involves stringent donor screening, anaerobic processing of fecal samples, preparation of germ-free or antibiotic-treated recipient mice, FMT via gavage, and final validation of microbiota engraftment using sequencing [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Microbiome-Disease Investigations

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Research | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Gnotobiotic Animal Models | Provides a controlled environment free of unknown microbes to study causality of transplanted human microbiota [4]. | Establishing HMA mice to test the inflammatory potential of donor microbiomes from IBD patients [4] [29]. |

| Antibiotic Cocktails | Depletes the native gut microbiota of conventional animals, creating "pseudo-germ-free" recipients for FMT studies [4]. | Preparing recipient mice for FMT to improve engraftment of donor microbiota [4]. |

| Cryoprotectants (e.g., Glycerol) | Preserves microbial viability during long-term storage of fecal samples at low temperatures [4]. | Maintaining integrity of donor fecal samples for later processing and FMT. |

| Anaerobic Chamber/Workstation | Creates an oxygen-free environment for processing fecal samples and preparing fecal suspensions to protect obligate anaerobic bacteria [4]. | Essential for the preparation of high-viability fecal suspensions for FMT. |

| 16S rRNA Sequencing Kits | Enables taxonomic profiling of microbial communities to assess composition and diversity [4] [27]. | Validating engraftment in HMA models and characterizing dysbiotic signatures in patient cohorts [4] [32]. |

| Shotgun Metagenomics Kits | Allows for strain-level identification and functional gene profiling of the entire microbiome [27]. | Analyzing shifts in metabolic pathways (e.g., SCFA synthesis) in disease states [28] [27]. |

| Metabolomics Kits & Standards | Facilitates the identification and quantification of metabolites (e.g., SCFAs, bile acids, tryptophan metabolites) in host samples [28] [5]. | Correlating microbial shifts with functional metabolic outputs in disease [28] [5]. |

The convergence of evidence from human studies, animal models, and advanced computational tools solidifies the role of specific microbial shifts in the pathogenesis of metabolic disorders, IBD, and cancer. While each disease exhibits a distinct microbial signature, common themes emerge, such as the loss of key commensal taxa, a decline in protective SCFA production, and dysregulation of host-microbiome co-metabolism in pathways involving amino acids and lipids. The translation of these findings from correlation to causation relies heavily on robust experimental models like HMA mice and genome-scale metabolic modeling. As these tools and datasets continue to mature, the path forward lies in leveraging this knowledge for precise diagnostics and targeted, microbiome-based therapeutics, ultimately paving the way for personalized medicine approaches in these complex diseases.

The field of microbiome therapeutics has evolved from a scientific curiosity to a rapidly expanding frontier in drug development. With over 180 drugs currently in development across more than 140 companies, this sector represents one of the most innovative areas in biopharmaceutical research. The market is projected to grow from approximately $791 million in 2025 to $6.09 billion by 2035, reflecting a compound annual growth rate of 20.4% [33]. This growth is fueled by a deeper understanding of the human microbiome's profound influence on various biological processes and the recognition that unlike many host determinants, it represents a readily accessible target for manipulation to promote health benefits [34]. This review provides a comprehensive overview of the current microbiome therapeutic pipeline, examines the critical role of animal models in translating these discoveries to human applications, and details the experimental methodologies advancing this promising field.

The Microbiome Therapeutic Pipeline: A Quantitative Landscape

The microbiome therapeutic landscape has expanded dramatically, characterized by diverse modalities targeting a broad spectrum of diseases.

Table 1: Microbiome Therapeutics Pipeline Overview (2025)

| Development Stage | Number of Candidates | Representative Examples | Key Indications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preclinical & Discovery | ~60% (≈108 drugs) | SNIPR001 (SNIPR Biome), Kanvas Biosciences programs | IBD, Immuno-oncology, various [35] [36] |

| Phase I Trials | ~20% (≈36 drugs) | EO2463 (Enterome), SER-155 (Seres Therapeutics) | Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma, Sepsis [37] [36] |

| Phase II Trials | ~15% (≈27 drugs) | VE202 (Vedanta Biosciences), ST-598 (Siolta Therapeutics) | Ulcerative Colitis, Allergy Prevention [35] |

| Phase III Trials | <5% (≈9 drugs) | VE303 (Vedanta Biosciences), MaaT013 (MaaT Pharma) | rCDI, Graft-vs-Host Disease [34] [35] [36] |

| Approved Drugs | 2 (FDA) | Rebyota (Ferring/Rebiotix), Vowst (Seres Therapeutics) | Recurrent C. difficile Infection [35] |

Table 2: Segmentation by Therapeutic Modality

| Modality | Mechanism of Action | Advantages | Limitations | Example Candidates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) & Derivatives | Transfer of complete or processed microbial communities from healthy donors | High efficacy in rCDI (>80%), holistic ecological approach [34] | Donor variability, pathogen transmission risk, manufacturing complexity [35] | Rebyota (approved), MaaT013 (Phase III) [35] |

| Defined Microbial Consortia | Rationally selected bacterial communities ("bottom-up") | Controlled composition, reproducible manufacturing, improved safety [34] [35] | May lack ecological complexity of full microbiota, challenging engraftment [34] | VE303 (Phase III), VE202 (Phase II) [34] [35] |

| Single-Strain Live Biotherapeutic Products (LBPs) | Single bacterial strain with defined pharmacological activity | Simple manufacturing, clear mechanism of action [34] | May not address complex dysbiosis, limited functional breadth | IBP-9414 (IBT), EXL01 (Exeliom) [37] |

| Engineered Microbes & Phages | Genetically modified bacteria or bacteriophages for precise targeting | High specificity, ability to deliver therapeutic payloads [37] [38] | Regulatory hurdles for GMOs, potential immune responses | SYNB1934 (Synlogic), Eligobiotics (Eligo Bioscience) [37] [35] |

The pipeline demonstrates significant clinical diversification. While recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection (rCDI) was the initial focus, developers are now actively targeting inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), metabolic disorders, autoimmune diseases, cancer, and neurological conditions [35]. Over 70 companies worldwide are engaged in developing therapies that manipulate the human microbiome [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Research Solutions

Advancing microbiome therapeutics requires specialized tools and reagents. The following table details key resources essential for research and development in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Microbiome Therapeutics Development

| Research Reagent / Solution | Primary Function | Application in Microbiome Research |

|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing Reagents | Amplification and sequencing of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene for taxonomic identification [39] | Profiling microbial community composition and diversity in fecal samples, tissue biopsies, and in vitro cultures [39] |

| Anaerobic Chamber Systems | Creation of oxygen-free environment for processing and culturing obligate anaerobic gut bacteria [4] | Preservation of microbial viability during fecal sample processing and cultivation of fastidious anaerobic species for LBPs [4] |

| Cryopreservation Protectants (e.g., Glycerol) | Protect bacterial cells from damage during freezing and thawing [4] | Long-term storage of donor fecal samples, defined microbial consortia, and single-strain LBPs while maintaining viability [4] |

| Germ-Free (Gnotobiotic) Animal Models | Animals devoid of any microorganisms, serving as a "blank slate" for microbial colonization studies [39] [40] | Investigating causal microbe-host interactions by colonizing with human-derived microbiota or specific bacterial strains [4] [40] |

| Multi-Omics Kits (Metagenomics, Metatranscriptomics, Metaproteomics, Metabolomics) | Comprehensive profiling of microbial genes, gene expression, proteins, and metabolites [41] | Understanding functional dynamics of the microbiome and mechanistic effects of therapeutic interventions [41] |

| Gnotobiotic Isolators | Sterile housing systems that maintain germ-free status or defined microbial status of animals [40] | Maintaining the integrity of Human Microbiota-Associated (HMA) animal models during long-term studies [4] [40] |

Experimental Models: Bridging the Gap from Animal Models to Human Trials

A critical challenge in microbiome research is the translatability of findings from animal models to human clinical trials. Human Microbiota-Associated (HMA) mouse models, established by transplanting human fecal microbiota into germ-free mice, have become an indispensable tool for investigating microbe-host interactions and disease pathogenesis [4].

Diagram 1: HMA Model Workflow for Therapeutic Development. This workflow outlines the critical steps in creating humanized gnotobiotic mouse models for microbiome therapeutic research, from donor screening to therapeutic translation.

Detailed Protocol: Establishing a Human Microbiota-Associated (HMA) Mouse Model

The establishment of a reproducible HMA model requires meticulous attention to donor selection, sample processing, and transplantation protocols [4] [40].

Donor Screening and Selection Criteria

- Inclusion Criteria: Healthy donors typically require a minimum of 2-12 months without antibiotic exposure, elimination of laxative agents for ≥3 months, an omnivorous diet, and absence of gastrointestinal disorders or recent pathogen infections [4].

- Exclusion Criteria: Common exclusions include recent exposure to antimicrobials, prebiotics, or probiotics (within 1-2 months), active neuropsychiatric disorders, excessive alcoholism or smoking habits, and pregnancy or lactation [4].

- Special Considerations: Donor diet, exercise, geographical origin, and ethnicity significantly influence gut microbiota composition and must be documented, as they affect the translatability of findings [40].

Fecal Sample Processing and Preservation

- Collection: Fecal samples should be collected anaerobically and processed immediately after passage to preserve viability of oxygen-sensitive commensals [4].

- Homogenization: Suspend fecal material in anaerobic, reduced PBS or similar buffer (typically 1:5-1:10 weight/volume) under anaerobic conditions [4].

- Filtration: Remove large particulate matter by filtration through sterile mesh (e.g., 100-500 μm) [4].

- Preservation: If not used immediately, add cryoprotectants (e.g., 10-15% glycerol) and store at -80°C or in liquid nitrogen. Multiple freeze-thaw cycles should be avoided [4].

Recipient Preparation and Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT)

- Recipient Models: Two primary options exist:

- Transplantation Protocol:

- Administration Route: Oral gavage is most common, but rectal installation is also used.

- Dosing Regimen: While a single gavage can establish colonization, multiple administrations (e.g., 3 times per week for 2-3 weeks) significantly improve donor microbiota engraftment efficiency [4].

- Post-FMT Monitoring: Allow 1-2 weeks for stable microbial ecosystem establishment before initiating experimental interventions.

Engraftment Validation

- 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing: The primary method for analyzing microbiome composition and verifying donor microbiota engraftment [4].

- Functional Metagenomics: Assess the functional potential of the transplanted microbiota [41].

- Metabolomic Profiling: Validate functional engraftment through analysis of microbially-derived metabolites (e.g., short-chain fatty acids) in recipient feces and serum [41].

Correlation Between Animal Model and Human Study Findings

The predictive value of animal models for human outcomes remains a central consideration in microbiome therapeutic development. Key findings and challenges include:

Successful Correlations: The high success rate of FMT for rCDI in humans (>80%) was reflected in animal studies, validating the model's predictive capability for this indication [34]. Similarly, studies using HMA models have successfully recapitulated human metabolic phenotypes, such as the transfer of lean and obese phenotypes through microbiota transplantation [40].

Limitations and Disconnects: Significant differences exist between mouse and human microbiota. Despite an 89% similarity in overall bacterial genera between clean laboratory mice and humans, a number of human-specific genera are completely absent in mice, including ones linked to gut health in humans [39]. Furthermore, germ-free mice have substantial physiological differences in their gastrointestinal tracts, including fewer Peyer's patches, smaller mesenteric lymph nodes, and reduced production of secretory IgA, which must be considered when interpreting results [39].

Standardization Challenges: Inadequate standardization in creating HMA models across research groups poses significant constraints on the effective translatability of the system [40]. Variations in donor selection, fecal processing methods, recipient mouse strain, and housing conditions can all influence experimental outcomes and reproducibility [39] [4].

Diagram 2: Iterative Research Framework for Microbiome Therapeutics. This framework illustrates the multi-stage approach recommended for translating correlational findings into successful clinical applications, emphasizing the iterative refinement process based on clinical feedback.

The pipeline of over 180 microbiome drugs in development reflects a field rich with innovation and potential. The progression from broad-spectrum FMT to precisely defined microbial consortia and engineered live biotherapeutics represents a maturation of the entire sector. The continued refinement of HMA animal models and standardized experimental protocols will be crucial for enhancing the translatability of preclinical findings to human applications. As these therapeutic candidates advance through clinical trials, they hold the promise of addressing not only gastrointestinal disorders but also a wide range of systemic conditions, fundamentally expanding our approach to disease treatment and prevention.

A Researcher's Toolkit: Experimental Models for Host-Microbiome Interaction Studies

In the investigation of host-microbe interactions, a fundamental challenge persists: distinguishing mere correlation from true causation. While large-scale sequencing and multi-omics approaches can identify microbial associations with health and disease, they fall short of proving mechanistic causality [41]. Germ-free (GF) animal models have therefore become indispensable tools, providing a controlled "blank slate" for rigorously testing hypotheses about microbiome function. These animals, completely devoid of all living microorganisms, allow researchers to dissect the specific contributions of microbiota to physiology and disease pathogenesis with a precision unmatched by other models [42] [43].

The value of GF models lies in their unique experimental flexibility. By maintaining animals in sterile isolators and then introducing defined microbial communities, scientists can move beyond observation to direct experimentation [44]. This approach has revealed the profound influence of gut microbiota on diverse bodily systems, including immune development, metabolic function, and even brain behavior through the gut-brain axis [43]. As microbiome research transitions from correlational findings to therapeutic applications, GF animals provide the critical experimental platform needed to validate causal links and advance our understanding of microbiome-based interventions.

Germ-Free vs. Antibiotic-Treated Models: A Comparative Analysis

Two primary approaches are used to study microbiota depletion in animal models: isolated germ-free systems and antibiotic-treated models. Each method offers distinct advantages and limitations, making them suitable for different research applications.

Table 1: Comparison of Germ-Free and Antibiotic-Treated Animal Models

| Characteristic | Germ-Free Models | Antibiotic-Treated Models |

|---|---|---|

| Microbial Status | Complete absence of all living microorganisms [42] | Drastically reduced microbial diversity and density [42] |

| Immune System | Underdeveloped; reduced immune cells & lymphoid tissues [44] | Altered but not completely ablated [42] |

| Cecal Morphology | Significantly enlarged cecum [44] | Mild to moderate cecal enlargement [42] |

| Experimental Control | Maximum control; known microbial composition [42] | Less control; residual microbes present [42] |

| Technical Demand | High (requires sterile isolators) [44] | Moderate (standard housing) [42] |

| Cost & Maintenance | High cost, labor-intensive [42] | Lower cost, easier maintenance [42] |

| Human Translation | Excellent for reductionist causality studies [4] | May better mimic antibiotic-exposed humans [42] |

Strengths and Limitations in Practice

Germ-free models provide the highest level of experimental control, creating a true "blank slate" with no historical microbial exposure [42]. This complete absence of microbes allows for precise colonization studies with defined microbial communities, enabling researchers to establish direct causal relationships between specific microbes and host phenotypes [43]. However, this approach requires specialized sterile isolator equipment and intensive maintenance, creating significant technical and financial barriers [44]. Additionally, the physiological adaptations to a microbe-free life—particularly the underdeveloped immune system and enlarged cecum—represent abnormal conditions that must be considered when interpreting results [44].

Antibiotic-treated models offer greater practicality and accessibility for many research settings [42]. The depletion (rather than elimination) of microbiota may better mimic common human conditions such as antibiotic exposure. However, these models face significant limitations including incomplete microbial eradication, potential off-target drug effects, and the inability to control for the composition of residual microbial communities [42]. The presence of remaining microbes or their components can confound experimental results and complicate causal interpretations.

Experimental Workflows and Key Methodologies

The power of GF models is fully realized through carefully designed colonization experiments. Two primary methodologies dominate the field: human microbiota-associated (HMA) models and defined microbial community applications.

Establishing Human Microbiota-Associated (HMA) Models

HMA models involve transplanting entire human microbial communities into GF recipients, creating "humanized" animals that carry a donor's gut microbiome [4]. This approach allows researchers to study the functional effects of human microbiomes in a controlled animal model.

Table 2: Key Stages in Establishing HMA Models

| Research Stage | Key Actions | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Donor Screening | Apply strict inclusion/exclusion criteria [4] | Exclude recent antibiotic/probiotic use (≥1-2 months); assess diet, health status, medications [4] |

| Sample Processing | Collect and process fecal samples anaerobically [4] | Minimize oxygen exposure; use cryoprotectants for storage; process quickly [4] |

| Recipient Preparation | Use GF or antibiotic-pretreated animals [4] | GF animals show superior engraftment; antibiotic pretreatment creates "pseudo-GF" state [4] |

| Transplantation | Administer fecal suspension via gavage [4] | Single gavage may suffice; multiple doses improve colonization efficiency [4] |

| Engraftment Validation | Analyze microbiome composition (16S rRNA sequencing) [4] | Verify donor microbiome profile establishment in recipients [4] |

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow for creating HMA mouse models:

Reductionist Approaches with Defined Microbial Communities

For mechanistic studies, GF animals can be colonized with defined, simplified microbial communities rather than complete human microbiota. This reductionist approach enables precise attribution of specific functions to individual microbial species or defined consortia, allowing researchers to dissect complex host-microbe interactions at a molecular level [42]. The resulting "gnotobiotic" animals (with known microbiota) provide a powerful platform for investigating microbial metabolism, immune modulation, and pathway-specific activities in ways not possible with complex, undefined communities.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Success in germ-free research depends on specialized materials and reagents that maintain sterility and enable precise experimentation.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Germ-Free Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Sterile Isolators | Maintain germ-free environment with physical barrier [44] | Require specialized equipment and training; regular sterility monitoring essential [44] |

| Gamma-Irradiated Feed | Provides sterile nutrition without live microorganisms [44] | Must be fortified to compensate for nutrient loss during sterilization [44] |

| Fecal Suspension Buffer | Preserves microbial viability during transplantation [4] | Anaerobic conditions and cryoprotectants enhance microbial survival [4] |

| Antibiotic Cocktails | Depletes microbiota in pseudo-germ-free models [42] | Must control for off-target drug effects; incomplete eradication [42] |

| 16S rRNA Sequencing | Verifies germ-free status and engraftment efficiency [4] | Primary method for analyzing microbiome composition [4] |

Research Applications and Key Findings

GF models have generated foundational insights across numerous biomedical fields by enabling causal inferences between microbiota and host physiology.

Establishing Causality in Disease Pathogenesis

GF animals have been instrumental in demonstrating that gut microbiota can directly influence disease development and progression. For example, studies have shown that transferring gut microbiota from humans with specific diseases (such as metabolic syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, or even neuropsychiatric conditions) to GF animals can transfer certain disease characteristics [4] [43]. This experimental paradigm provides compelling evidence for microbiota's causal role in disease pathogenesis, moving beyond correlational observations to mechanistic understanding.

Elucidating Host-Microbe Signaling Pathways

The diagram below illustrates how germ-free models help researchers dissect specific signaling pathways through which gut microbiota influence host physiology:

Research using this approach has revealed that microbiota suppress tonic Hedgehog signaling in the small intestine through Toll-like receptor (TLR2/TLR6) signaling, regulating intestinal barrier function [42]. Similarly, intestinal epithelial neuropilin-1 has been identified as a microbiota-dependent Hedgehog regulator that contributes to epithelial stabilization [42]. These findings exemplify the molecular precision possible with GF model systems.

Germ-free animal models remain irreplaceable tools for establishing causal links in microbiome research, providing the critical experimental platform needed to advance from correlation to mechanism. While each model system has distinct strengths and limitations, GF animals offer unparalleled control for reductionist studies of microbial function [42] [44]. As the field progresses toward clinical applications, these "blank slate" models will continue to enable rigorous testing of microbiome-based therapeutics and mechanistic investigations of host-microbe interactions across physiological systems.

The integration of GF models with multi-omics technologies and human microbiota-associated approaches creates a powerful framework for translational microbiome research [41] [4]. By combining the control of GF systems with the physiological relevance of human microbial communities, researchers can accelerate the development of novel microbiome-based diagnostics and interventions, ultimately bridging the gap between experimental models and human health.

The quest to establish causal links between the human gut microbiome and disease pathophysiology has positioned Human Microbiota-Associated (HMA) rodent models as indispensable tools in contemporary biomedical research. These models are created by transplanting human fecal microbiota into germ-free (GF) or antibiotic-pretreated rodents, enabling researchers to study human-specific microbial communities within a controlled laboratory setting [4] [45]. The fundamental premise underlying HMA models is their ability to transfer phenotypic traits from human donors to rodent recipients, thereby providing a causal experimental platform that transcends the correlative nature of human observational studies [45]. As the field of microbiome research rapidly expands, with implications for understanding conditions ranging from inflammatory bowel disease and obesity to neurological disorders and cancer immunotherapy responses, the proper utilization and critical assessment of HMA models becomes increasingly vital [4] [46] [45].

This comparison guide objectively examines the translational value of HMA rodent models by synthesizing current experimental data and methodological approaches. We present a balanced analysis of their significant contributions to mechanistic discovery alongside their inherent physiological constraints, with the aim of empowering researchers to design more interpretable and reproducible studies within the broader context of microbiome animal model human study findings correlation research.

Strengths of HMA Rodent Models

HMA rodent models offer several distinct advantages that have solidified their role in microbiome research.

Establishing Causality in Microbiome-Disease Relationships

The primary strength of HMA models lies in their ability to demonstrate causal relationships between specific human microbial communities and disease phenotypes. Unlike correlative human studies, HMA experiments can directly test whether microbiota from diseased individuals can induce or exacerbate pathophenotypes in recipient animals [45]. A recent scoping review of 489 studies revealed remarkably high success rates (>80%) in transferring disease-specific alterations for parameters including intestinal barrier function, gastrointestinal inflammation, circulating immune markers, and fecal metabolites [45]. This demonstrates the powerful phenotype transfer capability of these models across diverse disease contexts.

Environmental and Experimental Control

HMA models provide unprecedented control over variables that confound human studies, including genetic background, dietary composition, housing conditions, and medication exposure [47]. This controlled environment allows researchers to isolate the effects of the transplanted microbiota from other influencing factors, enabling rigorous hypothesis testing that would be impossible in human subjects [45]. Furthermore, the ability to manipulate these models through antibiotic treatments, dietary interventions, or pharmaceutical administration facilitates mechanistic studies exploring microbiome-host interactions [4].

Methodological Versatility and Phenotyping Depth

The flexibility of HMA protocols supports diverse research applications, from studying microbial community ecology to evaluating targeted therapeutic strategies [4]. Researchers can perform longitudinal sampling and access tissues for comprehensive multi-omics analyses, including metagenomics, transcriptomics, and metabolomics [48] [49]. This enables deep mechanistic insights into how transplanted human microbiota influence host physiology at multiple biological levels.

Table 1: Experimentally Demonstrated Phenotype Transfer Success Rates in HMA Models

| Outcome Category | Success Rate | Example Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Intestinal Barrier Function | >80% | Altered permeability, tight junction protein expression [45] |

| Gastrointestinal Inflammation | >80% | Increased pro-inflammatory cytokines, immune cell infiltration [45] |

| Circulating Immune Parameters | >80% | Changed T-cell populations, systemic cytokine levels [45] |

| Fecal Metabolites | >80% | Altered SCFA, bile acid, and tryptophan metabolite profiles [45] [48] |

| Behavioral Alterations | Reported | Depression/anxiety-like behaviors in neuropsychiatric disorder models [45] |

Limitations and Ecological Constraints

Despite their utility, HMA rodent models possess significant inherent limitations that affect their translational fidelity.

Incomplete Microbial Engraftment and Ecological Drift

A fundamental constraint of HMA models is the incomplete engraftment of human-derived microbial communities in rodent recipients. Multiple studies have demonstrated that only a taxonomically restricted set of human microbes successfully colonizes the murine gut, with consistent enrichment of specific taxa like Akkermansia muciniphila and Bacteroides species regardless of donor characteristics [46]. This engraftment limitation results in HMA mouse communities that resemble other mice more than their human donors, with one study reporting that "HMA mice were more similar to each other than the human donors or inoculum they are derived from" [46]. This ecological restructuring poses significant challenges for interpreting which specific microbial components drive observed phenotypes.

Physiological Disparities Between Species

The evolutionary divergence between humans and rodents creates fundamental differences in gastrointestinal anatomy, immune system function, and metabolic processes that limit translational potential [47]. Mice possess different bile acid compositions, faster intestinal transit times, and distinct immune cell distributions compared to humans [46]. These physiological differences create selective pressures that shape the transplanted microbiota differently than in the human donor, potentially altering microbial metabolism and host-microbe interactions [46]. Additionally, germ-free recipients used for HMA modeling have compromised immune development due to the absence of microbial exposure during early life, further diverging from human physiology [48] [47].

Methodological Heterogeneity and Standardization Challenges

Current HMA research suffers from significant methodological variability between research groups, hindering result comparability and reproducibility [4] [45]. Critical parameters including donor screening criteria, fecal processing methods, transplantation protocols, and engraftment validation approaches differ across studies [4]. A scoping review identified inconsistent reporting of key methodological aspects, making it difficult to assess technical quality or compare results across studies [45]. This lack of standardization represents a major challenge for the field.

Table 2: Comparative Engraftment Efficiency Across Different Recipient Models

| Recipient Model | Engraftment Efficiency | Notable Taxa | Developmental Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional HMA Mice | Limited, taxonomically restricted | Enrichment of Akkermansia, Bacteroides spp. [46] | Compromised immune development in GF recipients [48] |

| Two-Generation HMA Mice | Improved stability | Better retention of infant microbiota features [48] | Offspring show more developed immune systems [48] |

| HMA Piglets | Superior for child/adult/elderly microbiota | More donor species retained compared to mice [50] | Physiologically closer to humans; practical limitations |

Methodological Protocols for HMA Model Establishment

Standardized protocols are essential for generating reproducible HMA models. Below, we detail the critical methodological components based on current literature.

Donor Screening and Selection

Rigorous donor screening is paramount for HMA model validity. Comprehensive criteria should include:

- Medical History Assessment: Exclusion for recent antibiotic use (typically ≥1-2 months), gastrointestinal disorders, recent pathogen infections, and chronic illnesses that alter gut microbiota [4].

- Lifestyle Factors: Evaluation of dietary patterns, alcohol consumption, smoking status, and medication use (including probiotics and laxatives) [4].

- Laboratory Testing: Pathogen screening and basic health metrics to confirm donor status [4].

- Specialized Donor Groups: For disease-focused studies, donors must meet established diagnostic criteria for the condition under investigation, with careful consideration of comorbidities and concomitant medications that could confound results [4] [45].

Fecal Sample Processing and Preparation

Proper handling of fecal samples preserves microbial viability and integrity:

- Collection and Transport: Immediate freezing at -80°C or processing in anaerobic chambers to maintain anaerobic conditions [4] [46].

- Slurry Preparation: Homogenization in degassed phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with cryoprotectants (e.g., 20% glycerol), typically at 0.1-0.3 g/mL concentration [46] [48].

- Filtration: Removal of large particulate matter using 300µm filters to prevent gavage needle clogging [46].

- Quality Control: Assessment of microbial viability and composition stability before transplantation [4].

Recipient Preparation and Transplantation

- Recipient Status: Use of germ-free mice or antibiotic-pretreated conventional mice to create a microbial niche [4] [45]. Antibiotic cocktails typically include broad-spectrum drugs like ampicillin, vancomycin, neomycin, and metronidazole administered via drinking water for 1-2 weeks [45].

- Transplantation Route: Most studies utilize oral gavage with 200-250µL of fecal slurry [46] [45]. Multiple administrations (e.g., daily for 3 days) improve colonization efficiency [4].

- Environmental Transfer: Additional exposure via fur smearing and cage bedding transfer to enhance microbial exchange [46].

- Stabilization Period: Allow 2-4 weeks for microbial community stabilization before experimental procedures [46].

Diagram 1: HMA Model Establishment Workflow. The process involves sequential phases from donor screening through experimental phenotyping, with critical quality control checkpoints at each stage.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful HMA experiments require specific reagents and materials carefully selected to maintain microbial viability and ensure reproducible results.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for HMA Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Specification Considerations |

|---|---|---|