Controlling Confounding Factors in Microbiome Research: A Strategic Guide for Managing Age, Diet, and Antibiotic Variables

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to identify, understand, and control for major confounding factors in human microbiome studies.

Controlling Confounding Factors in Microbiome Research: A Strategic Guide for Managing Age, Diet, and Antibiotic Variables

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to identify, understand, and control for major confounding factors in human microbiome studies. It explores the foundational biology of how age, diet, and antibiotics shape microbial communities, offers methodological best practices for study design and sample processing, presents troubleshooting strategies for common experimental pitfalls, and outlines validation approaches for robust data interpretation. By synthesizing current evidence and methodological insights, this guide aims to enhance the reproducibility, accuracy, and clinical relevance of microbiome research across study cohorts and experimental conditions.

Understanding Core Confounders: How Age, Diet, and Antibiotics Fundamentally Reshape the Microbiome

The human gut microbiome undergoes a predictable yet dynamic succession from birth through old age, with its composition evolving in response to host physiology, diet, medications, and immune function. Understanding these progression patterns is crucial for microbiome researchers, as "biome-aging" (age-associated microbiome transformations) represents a key confounding factor in study design. The gut microbiome composition changes continually with age, influencing both physiological and immunological development, with emerging evidence highlighting its close association with healthy, disease-free aging and longevity [1]. This technical guide addresses the major experimental challenges in this field.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: What are the core, age-dependent microbial signatures I should account for in my cohort stratification?

- The Challenge: A study analyzing samples from adults aged 18-60 finds no significant correlation between microbiome composition and age. The researcher is unsure if the cohort is too narrow or if the analysis is missing key transitional taxa.

- The Solution: The core signature of aging is not just about the presence or absence of taxa, but a shift in community structure. Ensure your analysis looks for the specific transitions listed in Table 1, not just overall diversity. Stratifying your cohort into finer age brackets (e.g., 20-35, 36-50, 51-65) can reveal these subtler shifts that are masked in a broad age range.

FAQ 2: My intervention in an older adult population failed to change the microbiome diversity. Did the intervention fail?

- The Challenge: A clinical trial testing a prebiotic fiber in older adults (70+) shows no change in Shannon diversity, leading to the conclusion that the intervention was ineffective.

- The Solution: Diversity may not be the primary outcome of interest in older cohorts. A healthy aging gut is characterized by its specific taxonomic composition and functional output, not necessarily its highest diversity. You should analyze for:

- Taxonomic Shifts: Did the intervention increase the abundance of health-associated taxa like Akkermansia muciniphila, Christensenellaceae, or Bifidobacterium? [1] [2]

- Functional Restoration: Measure microbial metabolites, especially Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs) like butyrate. A successful intervention may not alter diversity but can significantly boost SCFA production, which is often diminished with age [1] [2].

FAQ 3: How do I control for the confounding effects of polypharmacy in aging studies?

- The Challenge: A study comparing healthy elderly to younger adults finds significant microbial differences, but the elderly cohort is on an average of 4 medications. It is unclear if the observed dysbiosis is due to age or medication.

- The Solution: This is a major confounder. Best practices include:

- Detailed Metadata Collection: Meticulously record all medications, including dosage and duration.

- Statistical Covariates: Include medication load (number of prescriptions) and specific drug classes as covariates in your statistical models.

- Medication-Matched Subgroups: If possible, recruit a subgroup of younger individuals on similar medications (e.g., metformin) to disentangle the effects of drugs from age itself.

FAQ 4: What is the best way to model human aging and microbiome interactions?

- The Challenge: A researcher wants to test the causal role of the aging microbiome on host physiology but cannot conduct fecal microbiota transplants (FMT) in humans.

- The Solution: Animal models are essential. The table below summarizes key model systems and their experimental readouts, based on established protocols [3].

Table 1: Experimental Models for Studying Microbiome and Aging

| Model System | Key Experimental Readouts | Troubleshooting Tip |

|---|---|---|

| Mouse (FMT from young to old) | Gut barrier integrity (e.g., serum markers), systemic inflammation (e.g., IL-6, TNFα), cognitive function, lifespan [2] [3]. | Use germ-free or antibiotic-treated recipients to ensure engraftment. Monitor for reversibility of effects. |

| African Turquoise Killifish | Locomotion, lifespan, behavioral decline [3]. | This model has a naturally short lifespan, allowing for rapid aging studies. |

| Drosophila melanogaster (Fruit Fly) | Lifespan, gut integrity, immune signaling [3]. | Culture conditions and nutritional environment drastically impact results; standardize food source. |

| Caenorhabditis elegans (Nematode) | Lifespan, mitochondrial function, stress resilience markers [3]. | Use defined bacterial mutants (e.g., E. coli) to probe specific microbial gene functions. |

Core Microbial Signatures Across the Lifespan

The following table summarizes the key microbial taxa and functional characteristics that change significantly across the human lifespan. These signatures should be considered as expected baselines or confounding factors in age-focused microbiome studies.

Table 2: Microbial Succession Signatures from Infancy to Centenarian Age

| Life Stage | Dominant Taxa & Shifts | Functional Characteristics | Key Confounding Factors to Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infancy (0-3 yrs) | Dominated by Bifidobacterium spp.; introduction of solid food enriches Bacteroides and Clostridium [1] [4]. | High capacity for human milk oligosaccharide (HMO) digestion; succession leads to enrichment of carbohydrate-degradation genes and SCFA production [4] [5]. | Delivery mode (C-section vs. vaginal), feeding type (breastmilk vs. formula), antibiotic exposure [4] [6]. |

| Adulthood (18-65 yrs) | Stable community dominated by Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes; high inter-individual variation at species level [1] [7]. | Stable metabolic output; core functional groups present. | Long-term dietary patterns, geography, alcohol consumption, sporadic antibiotic use. |

| Older Adulthood (65+ yrs) | Unhealthy Aging: Decreased diversity, loss of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, increase in Ruminococcus gnavus and Eggerthella lenta [8].Healthy Aging: Rise in Akkermansia, Christensenellaceae, and Bifidobacterium [1] [2]. | Reduced SCFA production; increased gut permeability ("leaky gut"); systemic inflammation (inflammaging) [1] [2]. | Polypharmacy, diet (reduced fiber intake), institutionalization, "inflammaging" status. |

| Centenarians (100+ yrs) | Unique phenotype: High microbial diversity, enrichment of Akkermansia, Christensenellaceae, and Bifidobacterium; capable of producing unique secondary bile acids [1] [9]. | Maintenance of intestinal homeostasis and colonization resistance; unique microbial metabolic profiles, including beneficial bile acid isoforms [1] [9]. | General frailty, extreme dietary adaptations, cumulative lifetime exposures. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Reagents & Protocols

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Age-Related Microbiome Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Probiotic Formulations | To test causal effects of specific taxa in restoring age-related dysbiosis. | Bifidobacterium bifidum & Lactobacillus acidophilus reduced pathobionts and ARGs in preterm infants [5]. |

| Defined Bacterial Mutants | To pinpoint microbial gene functions in host aging. | E. coli mutants with disrupted folate synthesis or enhanced colanic acid production extended C. elegans lifespan [3]. |

| Postbiotic Preparations | To isolate the effect of microbial components/metabolites without live bacteria. | Heat-killed Lactobacillus paracasei postbiotics improved gut barrier and reduced inflammation in aged mice [2]. |

| Specific Metabolites | To supplement and test direct host effects of microbial-derived molecules. | 3-phenyllactic acid from Lactiplantibacillus plantarum prolonged C. elegans lifespan [3]. |

| Gnotobiotic Animals | To host human-derived microbiota in a controlled, germ-free environment. | Mice humanized with centenarian microbiota showed reduced brain lipofuscin and longer intestinal villi [3]. |

Experimental Protocol: Analyzing the Gut Resistome in Age-Related Studies

Application: This protocol is critical for studies involving older adult populations or any cohort with high antibiotic exposure, as the "resistome" (collection of antibiotic resistance genes) is a significant confounding factor.

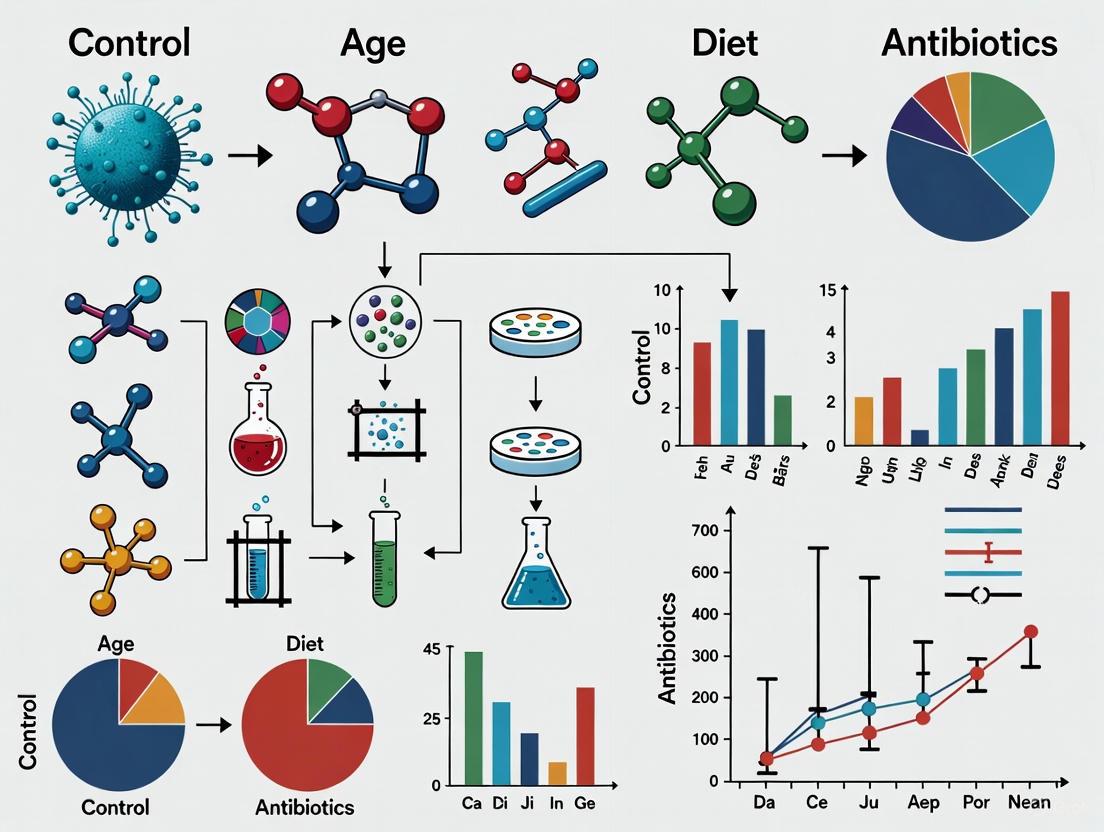

Workflow Diagram: The following diagram illustrates the key steps for a resistome analysis workflow, from sample collection to data interpretation.

Detailed Steps:

- Sample Collection & Sequencing: Collect fecal samples using a standardized kit for longitudinal studies. Perform shotgun metagenomic sequencing (e.g., Illumina) for comprehensive gene coverage, unlike 16S rRNA sequencing [5].

- Bioinformatic Processing:

- Quality Control: Use tools like FastQC and Trimmomatic to remove low-quality reads.

- Host DNA Removal: Align reads to the host genome (e.g., human GRCh38) using Bowtie2 and remove matching sequences.

- Assembly & Annotation: Assemble quality-filtered reads into contigs using metaSPAdes. Predict open reading frames (ORFs) from contigs. Annotate ORFs against a specialized database like the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD) using RGI [5].

- Resistome Analysis:

- Abundance & Diversity: Calculate the abundance (reads per kilobase per million, RPKM) of each ARG. Determine resistome diversity by counting the number of different ARG classes present (e.g., aminoglycosides, beta-lactams) [5].

- Statistical Integration: Correlate ARG abundance and diversity with microbial taxonomy (e.g., presence of Enterococcus or Klebsiella), clinical metadata (e.g., antibiotic treatment history), and functional pathway data.

Advanced Concepts & Visualization

The Gut-Brain Axis in Aging: A Mechanistic Workflow

The gut-brain axis is a critical pathway through which the aging microbiome influences host health, particularly neurocognitive decline. The following diagram outlines a hypothesized experimental workflow to dissect this mechanism, from inducing dysbiosis to measuring brain outcomes.

Key Mechanistic Insights:

- Dysbiosis & Barrier Failure: Aging is associated with a decline in SCFA-producing bacteria. SCFAs are crucial for maintaining gut barrier integrity. Their reduction can lead to a "leaky gut" [1] [2].

- Inflammaging: A leaky gut allows bacterial components (e.g., LPS) to enter circulation, triggering a chronic, low-grade inflammatory state known as "inflammaging," characterized by elevated IL-6 and TNFα [1] [2] [3].

- Impact on the Brain: Systemic inflammation can compromise the blood-brain barrier and activate the brain's immune cells (microglia), leading to neuroinflammation. This process is implicated in age-related cognitive decline and neurodegenerative diseases [2] [3]. Interventions like postbiotics that thicken the mucus layer and reduce gut permeability have been shown to improve cognitive function in aged mice [2].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is the background diet of my study cohort a critical confounding factor? The background diet can significantly alter the gut microenvironment, thereby affecting the efficacy of the interventions you are testing. For instance, diet can influence the gut microbiome and change the metabolism and gene expression of probiotics. It is recommended that trials of prebiotics and probiotics consider the impact of the background diet as a confounder [10].

FAQ 2: How can I account for inter-individual variation in microbiome response to dietary interventions? Interindividual responsiveness to specific diets is partially determined by differences in baseline gut microbiota composition and functionality [11]. The baseline gut microbial profile may be a predictor for an individual’s response. Therefore, detailed metabolic and microbial phenotyping at the start of a study is necessary to stratify participants or interpret variable responses [11].

FAQ 3: Are the effects of early-life dietary exposures relevant to adult health outcomes? Yes, early-life exposures to environmental factors, including maternal diet, can have long-lasting impacts on offspring health and the adult gut microbiome [12]. Studies in mouse models have shown that maternal nutritional deficiencies (e.g., protein or vitamin D) during gestation and lactation can have lasting effects on offspring gut microbiota composition and body weight, depending on the genetic background [12].

FAQ 4: Beyond current diet, what other historical factors should I consider? A person's medication history is a surprisingly strong factor. Research has found that drugs taken years—even decades—ago, including antibiotics, antidepressants, and beta-blockers, can leave lasting imprints on the gut microbiome. This underscores the importance of factoring in complete medication history when interpreting microbiome data [13].

FAQ 5: What is the balance between saccharolytic and proteolytic fermentation, and why is it important? The balance between carbohydrate (saccharolytic) and protein (proteolytic) fermentation in the gut seems to be an important determinant of host metabolism [11]. A shift toward proteolytic fermentation is often associated with the production of metabolites that can have detrimental effects on metabolic health. Dietary strategies that promote saccharolytic fermentation are generally considered beneficial [11].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: High inter-individual variability is obscuring the effect of my dietary intervention.

- Potential Solution: Increase your sample size. Due to the intrinsic high variation in microbiota composition, the number of subjects required to allow meaningful statistical comparisons is often higher than used for other types of biological analyses [14]. Furthermore, perform detailed baseline phenotyping of participants (including their gut microbiome and habitual diet) to use as covariates in your models or to stratify your cohort into more responsive subgroups [11].

Problem: My dietary intervention for constipation, specifically a high-fiber diet, is not producing the expected results.

- Potential Solution: Note that while a diet high in fiber has benefits for overall health, according to recent evidence-based guidelines, it is not a first-line, evidence-based option for chronic constipation. Instead, consider specific foods and supplements with proven effectiveness, such as psyllium, inulin-type fructans, kiwifruit, prunes, or magnesium oxide supplements [10].

Problem: My low FODMAP dietary intervention for IBS is met with poor patient adherence.

- Potential Solution: Be aware of common patient challenges. These include the misalignment between food preferences and the dietary regimen, difficulty in composing meals, and the burden of meal preparation. To improve adherence, provide clear, reliable sources of information and practical support in meal planning. Furthermore, new research suggests it may be possible to improve tolerance for FODMAPs by utilizing modified fiber gels like methylcellulose and psyllium [10].

Problem: The gut microbiome in my animal models is not consistent, jeopardizing reproducibility.

- Potential Solution: Control for legacy effects. The same line of mice from different facilities can have very different microbiotas. To minimize this, consider methods like cross-fostering or extended cohousing. Always source animals from the same facility and report their origin. The practice of repeating animal trials is also recommended to confirm findings across different microbial backgrounds [14].

Quantitative Data on Dietary Impacts

Table 1: Evidence-Based Dietary Components for Managing Chronic Constipation [10]

| Dietary Component | Example | Level of Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|

| Fiber Supplements | Psyllium, Inulin-type fructans | Effective |

| Probiotics | Multi-strain probiotics, Bifidobacterium lactis, Bacillus coagulans Unique IS2 | Effective |

| Mineral Supplements | Magnesium oxide | Effective |

| Whole Foods | Kiwifruits, Prunes, Rye bread | Effective |

| Water | High mineral content water | Effective |

Table 2: Key Microbial Metabolites from Macronutrient Fermentation [11]

| Fermentation Type | Primary Macronutrient | Key Metabolites | General Health Association |

|---|---|---|---|

| Saccharolytic | Dietary Fibers/Carbohydrates | Short-Chain Fatty Acids (e.g., acetate, propionate, butyrate) | Generally beneficial |

| Proteolytic | Dietary Proteins | Ammonia, Phenolic Compounds (e.g., indole), Branched-Chain Fatty Acids (BCFAs) | Often detrimental |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Designing a Controlled Dietary Intervention Study

- Baseline Phenotyping: Collect detailed metadata from participants, including habitual diet (using food frequency questionnaires), medication history (current and past), anthropometric measurements, and gut microbiome samples [13].

- Dietary Control: Provide all meals and snacks for the intervention period to ensure strict control over macronutrient and micronutrient intake. If this is not possible, use detailed daily food diaries and provide participants with specific food items.

- Sample Collection: Standardize the collection of biological samples (e.g., feces, blood). For fecal samples, ensure consistent timing, use standardized collection kits, and immediately freeze samples at -80°C [14].

- Microbiome Analysis:

- DNA Extraction: Use a single, validated kit for all extractions to minimize technical bias [14].

- Sequencing: Use 16S rRNA gene sequencing for community composition or shotgun metagenomics for functional potential and strain-level analysis [15].

- Bioinformatics: Process sequences through a standardized pipeline (e.g., QIIME 2) using Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) for higher resolution than traditional OTUs [16].

Protocol 2: Investigating Strain-Level Response to Diet

- Sample Preparation: Perform shotgun metagenomic sequencing on fecal DNA to achieve high sequencing depth (ideally >10 million reads per sample) [15].

- Bioinformatic Strain Identification: Use one of two primary methods:

- Single Nucleotide Variants (SNVs): Map sequences to a database of reference genomes to call SNVs. This requires deep coverage but offers high precision [15].

- Presence/Absence of Genes: Identify the presence or absence of genes from the microbial pangenome. This is sensitive to less abundant members but may not differentiate closely related strains [15].

- Association Analysis: Correlate the abundance of specific strains or their gene content with dietary intake data to identify strain-specific responders to nutritional components.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Kits for Microbiome Research

| Item | Function | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | To isolate total genomic DNA from complex samples (e.g., feces). | Use a single, validated kit for all samples in a study to minimize technical variation [14]. |

| 16S rRNA Primers | To amplify a variable region of the 16S gene for phylogenetic profiling. | Earth Microbiome Project primers (515F/806R) target the V4 region [12]. |

| Shotgun Metagenomic Library Prep Kit | To prepare sequencing libraries from fragmented genomic DNA for whole-genome sequencing. | Allows for strain-level and functional analysis [15]. |

| RNA Stabilization Reagent | To preserve RNA integrity for metatranscriptomic studies. | Critical for assessing the active functional profile of the community [15]. |

Analytical Pathways and Workflows

Diagram 1: Diet-Microbiome-Metabolism Pathway

Diagram 2: Precision Nutrition Workflow

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing Insufficient Microbiome Resilience Post-Antibiotic Perturbation

Problem: The gut microbiome fails to return to its pre-antibiotic state long after treatment cessation.

Investigation & Solutions:

- Check Patient Age: The microbiome of infants and children is significantly more vulnerable to long-term disruption than that of healthy adults. Antibiotic exposure during the first 6 months to 2 years of life can cause delays in microbiome maturation that persist for over a year [17] [18].

- Review Antibiotic Spectrum: Broad-spectrum antibiotics like meropenem, cefotaxime, and ticarcillin-clavulanate are associated with greater decreases in diversity compared to some narrower-spectrum agents [17].

- Evaluate Diet and Co-factors: A high-fat diet can exacerbate the effects of antibiotic exposure, leading to significant alterations in microbial community structure and host metabolism, including weight gain and changes in serum metabolites [19]. Underlying illness and travel history also modulate resilience [17].

- Consider Restoration Strategies: If resilience is poor, evidence supports investigating interventions like Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) or specific probiotics to direct recolonization, though these should be tailored to the individual [17].

Guide 2: Addressing High Variability in Antibiotic Perturbation Models

Problem: Inconsistent or unpredictable taxonomic shifts in animal or in vitro models after antibiotic administration.

Investigation & Solutions:

- Control for Genetic Background: Host genetics is a major confounding factor. Studies show the specific response to an antibiotic or dietary insult varies significantly among genetically distinct mouse strains and can be influenced by parent-of-origin effects [20].

- Standardize Experimental Diet: The background diet is a critical variable. Exposure to even trace levels of antibiotics (ng/L) under a High-Fat Diet (HFD) induces significant changes in body weight and short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) profiles that may not occur under standard diets [19].

- Account for Nutrient Competition: Recognize that antibiotic effects are not isolated. The drug's impact is reshaped by nutrient competition within the microbial community. A species may decline either due to direct drug sensitivity or because a competitor is better able to capitalize on the new nutrient landscape created by the drug [21].

- Verify Antibiotic Dosage and Route: For environmental exposure studies, ensure accurate, low-dose administration via drinking water to mimic trace environmental contamination rather than clinical therapeutic doses [19].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most critical factors that determine the impact of an antibiotic on the gut microbiome? The impact is governed by a combination of factors related to the host, the antibiotic, and the environment. Key considerations include the host's age and microbiome maturity, the spectrum and duration of antibiotic treatment, and co-modulatory factors such as diet and underlying health status [17]. The ecological principle of nutrient competition among gut bacteria also plays a fundamental role in shaping the final outcome [21].

Q2: How does the timing of antibiotic exposure, particularly in early life, influence long-term outcomes? The first 2-3 years of life are a critical developmental window for the microbiome. Antibiotic treatment during this period, and even intrapartum antibiotic exposure from the mother, results in greater disruption and delayed maturation of the microbial community. These effects can persist for over a year and are associated with microbiota "age regression," where the microbial maturity lags behind chronological age [17].

Q3: Are the effects of antibiotic exposure uniform across all individuals? No, effects are highly variable. Inter-individual differences in gut microbiota composition are large. Furthermore, host genetic differences significantly modulate susceptibility to environmentally induced dysbiosis. Studies in mice show that the long-term impact of early-life antibiotic exposure on adult gut microbiome composition is dependent on genetic strain [20].

Q4: What is "breakpoint drift" and why is it a confounder in antimicrobial resistance (AMR) surveillance? Breakpoint drift refers to the revisions over time to the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) breakpoints used to categorize bacteria as susceptible or resistant. These evidence-based updates mean that an isolate previously classified as susceptible might now be reported as resistant, independent of any biological change in the organism. This can create an illusion of rapidly rising resistance rates that is partly an artifact of shifting diagnostic standards, confounding long-term AMR trend analyses [22].

Q5: Beyond direct killing, how do antibiotics reshape the gut microbial community? Emerging research shows that antibiotics cause collateral damage by altering the gut's nutrient landscape. When a drug reduces certain bacterial populations, it changes the availability of nutrients. The bacteria most adept at consuming these newly available nutrients thrive, leading to a reshuffling of the community structure based on ecological competition, not just direct drug sensitivity [21].

Quantitative Data Tables

Table 1: Impact of Early-Life Antibiotic Exposure on Microbiome Metrics

| Exposure Scenario | Key Microbiome Findings | Timing of Effect | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intrapartum Antibiotics | ↓ Diversity at 1 month; ↑ ARG enrichment in infants at 6 months | Short & Intermediate-term (6 months) | [17] |

| Antibiotics in first 2 years | ↓ Diversity & ↓ species; Delayed microbiome maturation | Long-term (>1 year) | [17] |

| Neonates (NICU): Meropenem, Cefotaxime | Marked ↓ in microbiome diversity | Acute (during treatment) | [17] |

| Maternal Antibiotics (Mouse Model) | Altered adult offspring composition (e.g., Bacteroides, Akkermansia) | Long-term (8 weeks) | [20] |

Table 2: Effects of Trace Antibiotic Exposure in Mice under High-Fat Diet

| Antibiotic | Concentration | Key Metabolic & Microbiota Findings | Sex-Specific Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Azithromycin (AZI) | Environmental (ng/L) | Markedly ↑ SCFAs (acetate, butyrate, propionate); Altered microbial community | Significant body weight gain in male mice only |

| Ciprofloxacin (CIP) | Environmental (ng/L) | Altered serum hormones & metabolic profiles; Restructured microbe-host interactions | Significant body weight gain in male mice only |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Investigating Long-Term Effects of Early-Life Antibiotic Exposure

Objective: To assess the lasting impact of maternal antibiotic exposure combined with nutritional deficiencies on offspring gut microbiome and growth.

Methodology:

- Animal Model: Use a population of recombinant inbred intercross (RIX) mice from the Collaborative Cross (CC) to model human genetic diversity [20].

- Dams Diet & Exposure: Maintain dams on defined diets from 5 weeks prior to pregnancy until the end of lactation. Diets should include:

- Control (CON): Standard mouse control diet.

- Antibiotic-Containing (AC): Purified AIN93G diet with antibiotics.

- Low-Protein (LP): Protein-deficient diet.

- Low-Vitamin D (LVD): Vitamin D-deficient diet [20].

- Crossing Scheme: Generate F1 offspring from reciprocal crosses (e.g., CC011xCC001 and CC001xCC011) to control for parent-of-origin effects [20].

- Post-Weaning Standardization: After weaning, transfer all offspring to new cages and feed a standardized chow diet until adulthood [20].

- Outcome Measures:

- Host Phenotype: Monitor and record offspring bodyweight regularly until sacrifice at 8 weeks [20].

- Microbiome Analysis: Collect fecal samples at 8 weeks. Perform DNA extraction and 16S rRNA gene sequencing to assess microbial diversity, composition, and specific differential abundances (e.g., Bacteroides, Muribaculaceae, Akkermansia) [20].

Protocol 2: Modeling Environmental Antibiotic Exposure under Metabolic Stress

Objective: To evaluate the impact of chronic, low-dose antibiotic exposure on the gut-microbiota-metabolism axis under a high-fat diet.

Methodology:

- Antibiotic Administration: Administer antibiotics like Azithromycin (AZI) and Ciprofloxacin (CIP) to mice via drinking water at environmentally relevant concentrations (ng/L) for a long duration [19].

- Dietary Regimen: Maintain all mice on a High-Fat Diet (HFD) throughout the exposure period to simulate metabolic stress [19].

- Sample Collection and Analysis:

- Microbiota Profiling: Analyze cecal or fecal content using 16S rRNA gene sequencing to determine changes in microbial community structure [19].

- Metabolite Measurement: Quantify concentrations of key Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs) like acetate, butyrate, and propionate in cecal content using techniques like GC-MS [19].

- Host Metabolic Phenotyping: Track body weight and collect serum to analyze hormone levels and global metabolic profiles via metabolomics platforms [19].

- Data Integration: Perform correlation network analysis to restructure and visualize the microbe-SCFA and microbe-serum metabolite relationships [19].

Signaling Pathways & Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: Antibiotic Perturbation Ecosystem Dynamics

Diagram 2: Factors in Early-Life Antibiotic Response

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Antibiotic Perturbation Studies

| Item/Category | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Collaborative Cross (CC) Mice | Genetically diverse mouse population to model human genetic variation and identify genotype-specific responses to perturbation. | Studying how host genetics modulates the long-term impact of early-life antibiotic exposure on the adult gut microbiome [20]. |

| Defined Diets (e.g., AIN93G) | Precisely control nutritional variables. Can be modified to include antibiotics or create specific deficiencies (low protein, low vitamin D). | Investigating the interaction between maternal diet during gestation/lactation and antibiotic exposure on offspring outcomes [20]. |

| Environmental Dose Antibiotics | Administer antibiotics at very low concentrations (ng/L to μg/L) via drinking water to simulate real-world environmental exposure, not clinical treatment. | Assessing the health risks of trace antibiotic pollution in conjunction with metabolic stressors like a high-fat diet [19]. |

| 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing | Culture-independent method for taxonomic profiling of bacterial communities. Assesses diversity and composition changes post-perturbation. | Standard analysis for determining antibiotic-induced shifts in microbial community structure in fecal samples from mice or humans [17] [20]. |

| Metabolomics Platforms (e.g., GC-MS) | Quantify small-molecule metabolites. Used to measure Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs) and serum metabolic profiles. | Linking microbiome changes to functional host outcomes, such as altered SCFA production or systemic metabolic shifts after antibiotic exposure [19]. |

| Gnotobiotic & Culture Systems | Use of germ-free animals or complex cultured communities from fecal samples to establish controlled systems for testing perturbations. | Systematically testing the effect of hundreds of drugs on complex microbial communities to deduce ecological principles like nutrient competition [21]. |

Frequently Asked Questions: Controlling for Confounders in Microbiome Research

FAQ 1: What are the most critical confounders to control for in human gut microbiome studies? The most critical confounders include host diet, age, medication use (especially antibiotics), and fecal microbial load. Diet profoundly shapes microbial community structure, with high-fiber patterns consistently promoting beneficial, short-chain fatty acid-producing bacteria [23] [24]. Age is a major factor as the gut microbiota evolves from infancy to old age, influenced by diet, lifestyle, and physiological changes [25]. Medication, particularly antibiotics, can cause substantial and sometimes persistent shifts in microbial composition [16]. Recent evidence highlights that fecal microbial load (microbial cells per gram) is a major determinant of gut microbiome variation and can be a stronger explanatory factor for observed changes than the disease condition itself [26].

FAQ 2: How does microbial load act as a confounder, and how can I account for it? Microbial load acts as a confounder because sequencing data typically provides only relative abundances, not absolute quantities. A change in the relative abundance of one taxon can be caused by the actual expansion of that taxon or the decline of others. Machine-learning models can now predict fecal microbial loads from standard relative abundance data [26]. To account for this, researchers should:

- Adjust Statistical Models: Include predicted microbial load as a covariate in models analyzing disease-microbiome associations.

- Interpret with Caution: Recognize that many reported disease-associated microbial signatures may be linked to changes in overall microbial load rather than the specific disease [26]. Adjusting for this effect has been shown to substantially reduce the statistical significance of many purported disease-associated species [26].

FAQ 3: What are the best study designs to minimize confounding in microbiome research? Meticulous study design is key to obtaining meaningful results [16]. Recommended designs include:

- Longitudinal Studies: Tracking the same individuals over time to control for inter-individual variation.

- Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs): Especially for interventional studies (e.g., diet, probiotics).

- Cross-Sectional Studies with Careful Adjustment: For observational studies, ensure large sample sizes and record comprehensive metadata on potential confounders for statistical adjustment [16]. The use of positive and negative controls during sample processing and sequencing is also critical for improving reliability [16].

FAQ 4: How do confounders like diet and age interact to affect the host? Confounders often do not act in isolation but through intersecting pathways. For example, age-related changes in physiology can alter how the gut microbiota responds to dietary components. Furthermore, gut dysbiosis influenced by diet can promote systemic inflammation via increased intestinal permeability and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) translocation, contributing to age-related conditions like sarcopenia (muscle loss) and vascular stiffness [23] [24]. This creates a complex feedback loop where confounders interact to modulate host health.

FAQ 5: What statistical methods are used to analyze microbiome data while controlling for confounders? Common methods include:

- Beta-Diversity Analysis: Using measures like Bray-Curtis dissimilarity or UniFrac distance to quantify microbial community differences between sample groups, followed by PERMANOVA to test significance while including confounders as covariates [16].

- Differential Abundance Testing: Using specialized tools (e.g., DESeq2, edgeR, MaAsLin2) that can incorporate metadata variables to identify taxa associated with a primary variable of interest after accounting for confounders.

- Ordination Methods: Constrained ordination techniques like Redundancy Analysis (RDA) or Canonical Correspondence Analysis (CCA) can visualize how much of the microbial variation is explained by the primary factor versus confounders [16].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inconsistent or non-reproducible microbiome-disease associations

- Potential Cause: Inadequate control for major confounders such as diet, medication, or microbial load, leading to spurious findings.

- Solution:

- Collect Comprehensive Metadata: Systematically record detailed information on participant diet, medication history, age, and lifestyle at the time of sample collection.

- Predict and Adjust for Microbial Load: Implement a machine-learning-based approach to predict fecal microbial load from your relative abundance data and include it as a key covariate in all association models [26].

- Increase Sample Size: Ensure the study is sufficiently powered to detect effects after accounting for multiple confounders.

Issue 2: High variability within experimental groups obscuring treatment effects

- Potential Cause: High inter-individual variation in baseline microbiota composition, often driven by unaccounted lifestyle or genetic factors.

- Solution:

- Use a Paired or Crossover Design: Where possible, have individuals serve as their own controls.

- Employ Rigorous Sampling Controls: Use standardized sample collection kits with preservatives and include positive and negative controls in your sequencing batches to distinguish technical noise from biological signal [16].

- Pre-screen Participants: For interventional trials, consider pre-screening participants for baseline microbiota composition to create more homogenous groups.

Issue 3: Difficulty interpreting the biological mechanism linking a confounder to a health outcome

- Potential Cause: The pathway from confounder (e.g., poor diet) to host physiology (e.g., inflammation) is complex and involves multiple, interacting biological layers.

- Solution:

- Adopt Multi-Omics Integration: Correlate microbiome data with metabolomics data (e.g., measuring SCFAs, TMAO) and host immune markers (e.g., cytokines like IL-6, TNF-α) to map out functional pathways [23] [24].

- Utilize Mechanistic Animal Models: Employ germ-free or gnotobiotic mouse models to test causal relationships. For example, fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) from human donors to germ-free mice can demonstrate causality, as shown when FMT from hypertensive donors elevated blood pressure in mice [23].

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Conducting a Controlled Microbiome Intervention Study

- Participant Recruitment & Stratification: Recruit participants based on strict inclusion/exclusion criteria. Consider stratifying randomization by key confounders like age, BMI, and baseline microbial diversity.

- Sample Collection: Provide participants with standardized stool collection kits containing DNA/RNA stabilizers to preserve microbial integrity. Instruct them to record immediate diet, medication, and lifestyle data for the 3 days preceding sample collection.

- DNA Extraction & Sequencing: Use a validated, reproducible kit for DNA extraction. Include both a positive control (a mock microbial community with known composition) and negative extraction controls (no sample) in each batch to monitor performance and contamination [16].

- Bioinformatics Processing: Process raw sequencing data using a standardized pipeline like QIIME 2. Cluster sequences into Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) for higher resolution than traditional OTUs [16].

- Statistical Analysis:

- Calculate alpha-diversity (e.g., Shannon index) and beta-diversity (e.g., Bray-Curtis dissimilarity).

- Use PERMANOVA on the beta-diversity matrix to test for group differences, including terms for the intervention, age, sex, and predicted microbial load.

- Perform differential abundance testing with tools that correct for multiple comparisons and allow for covariate adjustment.

Protocol 2: Predicting and Adjusting for Fecal Microbial Load

- Data Preparation: Compile your taxa relative abundance table (e.g., from metagenomic sequencing).

- Model Application: Input the relative abundance data into a pre-trained machine learning model designed to predict microbial load [26]. (Note: Researchers may need to train their own model on a suitable reference dataset or use available software implementations).

- Covariate Integration: Use the predicted microbial load values as a continuous covariate in your downstream statistical models analyzing associations between microbiome features and health outcomes [26].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Microbiome Research |

|---|---|

| DNA Stabilization Buffers | Preserves microbial DNA/RNA integrity at the point of sample collection, preventing shifts in microbial composition post-collection. |

| Mock Microbial Communities | Serves as a positive control during DNA extraction and sequencing to assess technical variability, batch effects, and accuracy of the workflow [16]. |

| 16S rRNA Gene Primers | Targets conserved regions for amplicon sequencing, enabling taxonomic profiling of bacterial and archaeal communities. |

| Probiotics (e.g., specific Lactobacillus strains) | Live microorganisms used in intervention studies to investigate their effect on modulating the gut microbiome and host health [25]. |

| Prebiotics (e.g., FOS, GOS, Inulin) | Substrates (often fibers) selectively utilized by host microorganisms to confer a health benefit; used to test dietary modulation of the microbiota [25]. |

| Synbiotics | Combinations of probiotics and prebiotics that work synergistically to enrich the supplemented probiotic in the gut [25]. |

| Germ-Free Mouse Models | Animals with no resident microbiota, used for fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) studies to establish causality between a donor's microbiome and a host phenotype [23] [24]. |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Diagram: Confounder-Microbiome-Host Health Pathways

Diagram: Microbiome Analysis Workflow

Research Design and Execution: Practical Protocols for Confounder Control

FAQ & Troubleshooting Guide

Q1: Why is age-matching so critical in case-control microbiome studies? The human microbiome evolves throughout life. The gut microbiota stabilizes around age 3 but continues to change in later life. For instance, institutionalized elderly individuals often develop high levels of Proteobacteria [27]. Using age-matched controls is therefore essential to ensure that observed microbial differences are linked to the disease state and not to natural, age-related variations in the microbial community [27].

Q2: My study involves animal models. What is a "cage effect" and how can I control for it? In mouse studies, animals housed in the same cage share similar gut microbiota due to behaviors like coprophagia. One study found that while mouse strain accounted for 19% of the variation in gut microbiota, cage effects contributed to 31% [27]. To control for this, you must set up multiple cages for each study group and statistically treat "cage" as an independent variable in your final analysis. It is acceptable to house two to three mice per cage to manage costs [27].

Q3: Beyond age and diet, what other host variables are major confounders? Machine learning analyses of large datasets have identified several strong sources of gut microbiota variance. If these variables are not evenly matched between cases and controls, they can produce spurious microbial associations with disease. Key confounders include [28]:

- Alcohol consumption frequency: A surprisingly strong source of variance that acts in a dose-dependent manner.

- Bowel movement quality: A robust factor that segregates microbiota profiles.

- Body Mass Index (BMI), sex, and geographical location.

The table below summarizes the quantitative impact of matching cases and controls for these confounding variables.

Table 1: Impact of Confounder-Matching on Observed Microbiota Differences

| Disease Category | Number of Diseases Studied | Reduction in Microbiota Differences After Matching | Notes and Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Various Diseases | 13 out of 19 | Yes | Matching for host variables like alcohol, BMI, and age reduced observed community differences [28]. |

| Type 2 Diabetes (T2D) | 1 | Yes (Substantial) | The greatest drop in signal occurred for T2D. Unmatched studies found significant differences, but matching for alcohol, BMI, and age drastically reduced these differences [28]. |

| Clinical Depression, ASD, Migraine | Several | Yes (Complete) | Statistically significant microbiota differences were lost when cases were compared to confounder-matched controls [28]. |

| IBD, Skin Conditions | Several | No | Significant microbiota differences persisted even after matching, indicating a strong disease-specific signal [28]. |

Q4: I have already collected my data without perfect matching. Can I statistically adjust for confounders? While statistical adjustments in linear mixed models can be used, they have limitations. In one T2D study, adding BMI, age, and alcohol intake as covariates reduced the number of spurious microbial associations from 5 to 2. However, the remaining associations were still linked to the confounding variables themselves, not the disease. In contrast, careful subject selection via matching eliminated all false positives, highlighting that statistical adjustment is not a perfect substitute for robust experimental design [28].

Q5: How does dietary standardization improve cross-cohort validation of microbiome biomarkers? Diet is a primary driver of gut microbiota composition [27]. Without dietary control, disease-associated microbial signals can be obscured by noise from dietary variations between cohorts. This is a key reason why microbiome-based classifiers for intestinal diseases (where diet has a direct and potent effect) show better cross-cohort validation performance (~0.73 AUC) than non-intestinal diseases [29]. Standardizing diet, or at least meticulously recording it for matching, is therefore a critical strategy for improving the reproducibility of findings across independent study populations.

Experimental Protocols for Confounder Control

Protocol 1: A Workflow for Matched Cohort Selection in Human Studies This protocol outlines a step-by-step process to select control subjects that minimize confounding effects.

Protocol 2: Designing an Animal Study to Mitigate Cage Effects This protocol ensures that cage effects do not confound the experimental results in rodent models.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Materials for Standardized Microbiome Cohort Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| OMNIgene Gut Kit | Allows stable at-room-temperature preservation of fecal samples for DNA analysis [27]. | Critical for sample collection in the field or where immediate freezing at -80°C is not possible. |

| 95% Ethanol | A low-cost preservative for fecal samples when freezing is not immediately available [27]. | An effective alternative to commercial kits for stabilizing microbial community DNA. |

| FTA Cards | Solid support matrix for room-temperature storage of fecal samples for DNA analysis [27]. | Useful for easy transport and storage of samples from remote collection sites. |

| Uniform DNA Extraction Kits | To purify microbial DNA from all samples in a study [27]. | Purchase all kits needed in a single batch at the study's start to minimize reagent lot-to-lot variation, a significant source of technical bias. |

| Synthetic DNA Controls | Non-biological DNA sequences used as positive controls in high-volume analyses [27]. | Helps monitor technical performance and identify potential contamination across sample processing batches. |

Quantitative Data on Confounding Effects

The following table compiles data from a large-scale analysis that used machine learning (Random Forests) to quantify how strongly various host variables are associated with human gut microbiota composition.

Table 3: Host Variables as Sources of Microbiota Heterogeneity

| Host Variable | Strength of Microbiota Association | Notes on Confounding Potential |

|---|---|---|

| Alcohol Consumption | High (AUROC >0.65) | A strong, dose-dependent confounder. Found to have non-zero confounding effects in several diseases, not limited to T2D [28]. |

| Bowel Movement Quality | High (AUROC >0.65) | An unexpectedly strong source of gut microbiota variance that should be reported and matched for [28]. |

| Dietary Variables | High (AUROC >0.65) | Includes intake frequency of meat/eggs, dairy, vegetables, whole grains, and salted snacks [28]. |

| BMI | High (AUROC >0.65) | A well-known confounder that is often unevenly distributed between diseased and healthy subjects [28]. |

| Geography | High (AUROC >0.65) | Reflects regional differences in lifestyle, diet, and environment [28] [29]. |

| Age | High (AUROC >0.65) | Microbiome composition changes from infancy to old age, making age-matching fundamental [28] [27]. |

| Sex | High (AUROC >0.65) | The gut microbiome can serve as a virtual endocrine organ, producing metabolites that interact with sex hormones [27]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Incomplete or Inaccurate Medication Histories

Problem: Patient medication lists are incomplete, missing antibiotics, or contain inaccurate dosage/frequency information, compromising microbiome study data quality.

Symptoms:

- Discrepancies between patient-reported medications and electronic health records

- Missing over-the-counter antibiotic medications

- Incomplete documentation of dosage, duration, or timing

- Lack of documentation for medications prescribed by multiple providers

Solutions:

- Implement Systematic Documentation Processes: Develop standardized medication history flowcharts specifying responsible personnel, information requirements, documentation locations, and monitoring processes [30].

- Enhance Patient Engagement: Incorporate language in appointment reminders asking patients to bring complete medication lists, including all prescribed, over-the-counter, and herbal medications [30].

- Leverage Technology: Configure electronic health records to prompt staff to document medication history processes and clearly display patient allergies, triggering alerts if conflicting medications are prescribed [30].

- Cross-Reference Multiple Sources: Verify medication information across pharmacy records, primary care providers, and specialist reports to ensure completeness [30].

Guide 2: Confounding Variables in Microbiome Analyses

Problem: Unaccounted host variables create spurious associations between antibiotic exposure and microbiome outcomes.

Symptoms:

- Inconsistent microbiome findings across studies examining similar antibiotics

- Inability to replicate published results

- Significant microbiome differences disappearing after controlling for specific host factors

Solutions:

- Systematically Match Cases and Controls: Prioritize matching for high-impact confounders identified through machine learning approaches, including alcohol consumption frequency, bowel movement quality, BMI, age, and dietary patterns [28].

- Implement Comprehensive Data Collection: Capture recommended host variables for all study participants to enable post-hoc matching and statistical adjustment [28].

- Validate Findings Across Multiple Matching Strategies: Compare results using different matching approaches (full matching, leave-one-out matching) to assess robustness of antibiotic-microbiome associations [28].

Guide 3: Geographic and Population Biases in Microbiome Data

Problem: Research datasets are dominated by samples from Western populations, limiting understanding of antibiotic impacts across diverse geographies.

Symptoms:

- Limited generalizability of findings to underrepresented populations

- Inability to account for regional differences in baseline microbiome composition

- Poor understanding of antibiotic impacts in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs)

Solutions:

- Diversify Sample Collection: Intentionally recruit participants from underrepresented regions, particularly LMICs where antibiotic usage patterns differ significantly [31] [32].

- Account for Regional Baseline Differences: Recognize that gut microbiome composition varies substantially across countries and is influenced by diet, ethnicity, and environmental factors [31].

- Contextualize Antibiotic Resistance Patterns: Monitor gut microbiomes as antibiotic resistance gene reservoirs, particularly in regions with high antibiotic usage and limited regulation [31].

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What specific host variables most strongly confound antibiotic-microbiome association studies? Research indicates alcohol consumption frequency and bowel movement quality are unexpectedly strong confounding variables. Machine learning analyses reveal these factors robustly segregate microbiota profiles and often differ in distribution between healthy and diseased subjects, creating spurious associations if not properly controlled [28].

Q2: How do antibiotic impacts on the microbiome differ between children and adults in LMICs? Children demonstrate more pronounced and prolonged disruptions than adults. Antibiotic exposure in children is associated with greater reductions in microbial diversity and lower recovery potential. Adult resistomes show higher antibiotic resistance gene abundance, though functional changes occur across age groups [32].

Q3: What are the limitations of statistical adjustment compared to careful subject matching? Statistical adjustments in linear mixed models may reduce but not eliminate spurious associations. In type 2 diabetes microbiota studies, statistical adjustment reduced significant ASVs from 5 to 2, but these remaining associations still reflected confounding variables rather than true disease signals. Careful subject matching eliminated all spurious associations [28].

Q4: How long do antibiotic-driven resistome changes persist? Evidence suggests limited resistome recovery compared to microbiome composition. Antibiotic-induced enrichment of resistance genes can persist for months following treatment, creating a reservoir for horizontal gene transfer even after taxonomic composition appears restored [32] [33].

Q5: What specific methodological factors contribute to inconsistent findings across antibiotic-microbiome studies? Substantial heterogeneity exists in study methodologies, including sampling timing, duration, sequencing approaches, and geographic settings. Currently available research shows considerable variation in these methodological factors, limiting insights into true antibiotic impacts [33].

Quantitative Data Tables

Table 1: Confounding Variable Impact on Microbiota Analyses

| Confounding Variable | Machine Learning AUROC* | Reduction in Microbiota Differences When Controlled | Diseases Most Affected |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol Consumption Frequency | 0.68 (High) | 20-45% reduction | Type 2 Diabetes, Migraine, Lung Disease |

| Bowel Movement Quality | 0.67 (High) | 15-40% reduction | Autism Spectrum Disorder, Depression |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | 0.65 (Medium) | 10-35% reduction | Type 2 Diabetes, Thyroid Disease |

| Age | 0.63 (Medium) | 5-25% reduction | Multiple Chronic Conditions |

| Dietary Patterns | 0.61-0.66 (Medium) | 10-30% reduction | Metabolic Syndrome, IBD |

*AUROC (Area Under Receiver Operating Characteristic) values quantify ability of microbiota data to discriminate samples based on host variables (values >0.65 indicate strong associations) [28].

Table 2: Antibiotic Impacts on Gut Microbiome in LMICs

| Parameter | Children (<2 years) | Adults | Recovery Timeline |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha Diversity Reduction | Severe (50-70% decrease) | Moderate (30-50% decrease) | Partial recovery by 1-3 months |

| Taxonomic Disruption | Pronounced loss of commensals | Selective taxa alteration | Variable, often incomplete |

| ARG Enrichment | Moderate, but prolonged | Higher baseline, selective | Limited resistome recovery |

| Functional Consequences | Immune development impairment | Metabolic pathway alteration | Unknown long-term effects |

| Key Risk Factors | Multiple antibiotic courses | Cumulative lifetime exposure | Dose-dependent recovery |

Data synthesized from systematic reviews of LMIC studies [32] [33].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Medication History Documentation for Microbiome Studies

Purpose: Standardized approach for documenting antibiotic exposures in research participants to minimize recall bias and incomplete data.

Materials:

- Electronic data capture system

- Standardized medication history questionnaire

- Pharmacy verification access

- Timeline follow-back methodology materials

Procedure:

- Pre-Visit Preparation:

- Send medication documentation instructions with appointment reminders

- Request patients bring all medication containers, including supplements

- Obtain releases for pharmacy and provider records

Structured Interview:

- Conduct medication history using standardized questionnaire

- Utilize timeline follow-back method for accurate recall

- Specifically probe for antibiotic use in previous 3, 6, and 12 months

- Document name, dosage, duration, and indication for each antibiotic course

Verification Process:

- Cross-reference with pharmacy dispensing records

- Verify with primary care and specialist providers

- Resolve discrepancies through patient follow-up

Data Integration:

- Record complete medication history in standardized format

- Document confidence level for each data element

- Flag uncertain information for potential exclusion in sensitivity analyses

Validation: Implement data quality checks comparing patient report to objective records, calculating concordance rates [30] [28].

Protocol 2: Confounding Variable Assessment and Matching

Purpose: Systematic approach to identify and control for host variables that confound antibiotic-microbiome associations.

Materials:

- Host variable assessment questionnaire

- Data management system for matching algorithms

- Statistical software for propensity score calculation

Procedure:

- Baseline Assessment:

- Collect demographic, lifestyle, and clinical variables

- Include alcohol frequency, bowel movement quality, diet, BMI, age, sex

- Document complete medication history per Protocol 1

Matching Algorithm Implementation:

- Calculate propensity scores based on confounding variables

- Implement Euclidean distance-based pairwise matching

- Prioritize matching for strongest confounders (AUROC >0.65)

Quality Control:

- Assess balance between groups after matching

- Verify no significant differences in confounding variables

- Document matching quality metrics

Sensitivity Analyses:

- Compare results across different matching strategies

- Conduct leave-one-out analyses to identify most influential confounders

- Perform stratified analyses by key variables [28]

Workflow Visualization

Medication History Documentation Pathway

Confounding Factor Control System

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Materials for Antibiotic-Microbiome Studies

| Research Tool | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Standardized Medication History Questionnaire | Documents antibiotic exposure history | Must include specific probing for timing, dosage, duration; should incorporate verification mechanisms |

| Host Variable Assessment Battery | Captures confounding variables | Should include alcohol frequency, bowel movement quality, dietary patterns, BMI, demographic factors |

| Electronic Data Capture System | Standardizes data collection | Configured with validation rules and quality checks; enables reproducible data collection |

| Matching Algorithm Software | Controls for confounding | Implement propensity score or Euclidean distance-based matching; R or Python packages recommended |

| Microbiome Sequencing Platforms | Characterizes microbial communities | 16S rRNA for taxonomic profiling; shotgun metagenomics for functional and resistome analysis |

| Antibiotic Resistance Gene Databases | Identifies resistome elements | CARD, ARDB, or custom databases for tracking antibiotic resistance genes |

| Quality Control Metrics | Ensures data reliability | Include positive and negative controls; implement batch effect correction |

Based on methodologies from cited studies [31] [28] [32].

This guide addresses frequently asked questions to help you preserve sample integrity and mitigate common confounding factors in microbiome research.

Why is controlling for host variables like age and diet so critical in microbiome study design?

Failure to control for major host variables can lead to spurious associations and false positives, as these factors often explain more variation in microbial composition than the disease condition itself [28] [34] [26].

Key Confounding Host Variables

| Host Variable | Impact on Microbiome | Recommendations for Control |

|---|---|---|

| Age | A major determinant of microbiome composition; disease-associated signatures can be age-specific [34]. | Match cases and controls by age group; use age-adjusted statistical models [34]. |

| Diet | A primary driver of microbiome variation; responses can be highly personalized [35]. | Collect multiple days of dietary history prior to sampling; consider controlled dietary interventions [35]. |

| Alcohol Consumption | An unexpectedly strong source of gut microbiota variance that can confound disease associations [28]. | Record frequency and amount; match cases and controls for this variable [28]. |

| Bowel Movement Quality | A robust source of gut microbiota variance [28]. | Document stool quality using standardized scales (e.g., Bristol Stool Chart). |

| Fecal Microbial Load | The major determinant of gut microbiome variation; changes in load can be mistaken for disease associations [26]. | Use methods to predict or measure microbial load and adjust for it statistically [26]. |

What are the best practices for collecting and storing stool samples?

Optimal stool collection and storage are paramount for preserving microbial community structure and function.

Experimental Protocol: Comparing Preservation Buffers

A systematic evaluation tested the performance of different preservation buffers when storing human stool samples at various temperatures for up to three days, compared against immediately snap-frozen stool [36].

Key Methodology:

- Samples: Stool from 6 healthy subjects.

- Processing: Homogenized within 1 hour of collection.

- Preservation Conditions: 1-gram aliquots were added to tubes containing 8 ml of RNAlater, 95% ethanol, Invitek PSP buffer, or kept dry.

- Storage: Samples were stored at room temperature (20°C), 4°C, or –80°C.

- Analysis: 16S rRNA gene sequencing and SCFA profiling via GC-MS.

Results Summary:

| Preservation Buffer | DNA Yield | Closeness to Original Microbiota (16S profile) | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSP Buffer | High (similar to dry) | Closest | Best all-around performer for DNA and microbial diversity. |

| RNAlater | Low (requires a PBS wash step) | Very Close | Effective after washing step; suitable for metabolomics. |

| 95% Ethanol | Significantly Lower | Variable/Poor | High failure rate in sequencing; not recommended. |

| Dry (Unbuffered) | High | Divergent | Significant microbial change over time; not recommended for room-temperature storage. |

Conclusion: PSP and RNAlater were the most effective buffers for preserving microbial community structure at ambient temperatures, closely recapitulating the snap-frozen control [36]. Immediate freezing at –80°C remains the gold standard when feasible [37].

How do we prevent contamination in low-biomass microbiome samples (e.g., urine)?

Samples like urine have a low microbial biomass, making them highly susceptible to contamination that can lead to false positives.

Key Contamination Prevention Strategies

- Use of Controls: Always include DNA extraction blanks and non-template controls to identify reagent or environmental contaminants [38].

- Collection Method: Clearly distinguish and report collection methods. Catheterization or cystoscopic collection provides a "urinary bladder" sample, while voided samples represent a "urogenital" microbiome and are prone to urethral and skin contamination [37] [38].

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Use gloves and other PPE during collection and handling [37].

- Sterile Materials: Use sterile collection materials and work in decontaminated environments [37].

- Sample Volume: For catheter-collected urine, larger volumes (30–50 ml) are recommended to obtain sufficient bacterial DNA for analysis [38].

What technical challenges are associated with DNA extraction and sequencing?

Technical variations in DNA extraction and sequencing can introduce significant bias.

DNA Extraction

- Kit Selection: Different DNA isolation kits can produce varying total DNA concentrations, but studies show they can yield comparable 16S-specific sequence depths and alpha/beta diversity metrics [38].

- Standardization: Use the same validated extraction kit across all samples within a study to ensure consistency [37].

Sequencing Approach

| Method | Pros | Cons | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA Amplicon | Cost-effective; well-established | Primer selection bias (e.g., V4 may underestimate richness); lower resolution | Community-level profiling and diversity studies [37] [38] |

| Shotgun Metagenomic | Provides genomic and functional data; higher resolution | More expensive; computationally intensive | Identifying specific microbial genes and pathways [37] [38] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| OMNIgene•GUT (OMR-200) | Self-collection kit that stabilizes stool DNA at room temperature for up to 60 days [39]. | Home-based stool collection for large cohort studies. |

| RNAlater | Preservative that stabilizes nucleic acids in tissue and bacterial samples. | Preserving stool for simultaneous DNA and RNA analysis; requires a washing step for optimal DNA yield [36]. |

| PSP (Stool Stabilising Buffer) | Liquid buffer designed to preserve microbial community structure in stool at room temperature. | Ambient temperature storage and transport of stool samples for 16S sequencing [36]. |

| AssayAssure | Nucleic acid stabilizer added directly to urine samples in a 1:10 ratio to preserve microbial DNA [38]. | Stabilizing low-biomass urine samples during storage and transport. |

| BD Vacutainer Plus Urine Tubes | "Gray top" tubes recommended for urine sample collection for culture-based analysis [38]. | Standardized collection of urine for microbiological study. |

| Catch-All Swabs | Soft, foam swabs with plastic handles for general collection from oral cavity and other surfaces [39]. | Non-invasive sampling of oral, skin, or vaginal microbiomes. |

Workflow and Conceptual Diagrams

Sample Integrity Workflow

Confounding Variable Relationships

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. How do environmental variables like geography and co-housing act as confounding factors in microbiome studies? Environmental variables are major drivers of microbiome composition and can introduce significant variation that confounds the analysis of primary research questions. Geography influences microbial exposure through local climate, diet, and environmental microbes [40]. Cohousing, a form of shared environment, leads to microbial exchange between individuals, which can mask or exaggerate effects attributed to other factors if not controlled for [41]. Proper study design and statistical control are essential to account for this shared microbial reservoir [42].

2. What is the best way to control for pet ownership in a human microbiome study? The most robust method is to treat pet ownership as a covariate in your statistical model. During the study design phase, you should systematically record pet ownership status (type of pet, number, indoor/outdoor access) for all participants using a standardized questionnaire [41]. During analysis, you can then include this data as a fixed effect in linear models (e.g., using MaAsLin2) or similar tools to partition the variance explained by pets from the variance explained by your primary variable of interest [42].

3. Our study involves sampling from multiple geographic locations. How can we prevent technical bias from overwhelming true biological signals? Implementing a standardized protocol across all sites is critical. This includes using identical sample collection kits, storage conditions (e.g., -80°C), DNA extraction kits, and sequencing platforms [43]. Furthermore, you must incorporate and sequence negative controls (e.g., empty collection tubes, sterile swabs) and positive controls (e.g., mock microbial communities) at each site. These controls allow you to identify and computationally subtract contamination and technical artifacts introduced during sampling and processing, which is especially vital for low-biomass samples [44].

4. We've detected a significant cohousing effect. How can we determine if it's a true signal or a result of cross-contamination? True cohousing effects are typically characterized by the increased sharing of specific, plausible microbial taxa over time. To rule out technical cross-contamination, you should:

- Check your negative controls: The taxa driving the cohousing signal should not be present in your extraction or sequencing negative controls [44].

- Analyze longitudinal data: A true signal will show convergence of microbiome profiles between co-housed individuals across multiple timepoints, not just in a single sample [41].

- Review laboratory procedures: Ensure that samples from co-housed individuals were not processed in the same batch in a way that could cause well-to-well leakage during DNA extraction or library preparation [44].

5. What statistical methods are recommended for analyzing microbiome data with complex environmental covariates like geography? A multi-faceted approach is best. Start with data transformation (e.g., Centered Log-Ratio) to handle the compositional nature of the data [42]. For global association testing, methods like PERMANOVA can test whether overall microbiome composition differs by geographic region. To model the influence of multiple covariates (e.g., geography, diet, age) on individual microbial taxa, use multivariate methods specifically designed for microbiome data, such as those benchmarked for integrating multiple data types [42]. Always include relevant environmental variables in your models to isolate the effect of your primary variable of interest.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Unexpected Strong Geographic Signal Obscuring Primary Variable

Problem: After sequencing, primary analysis reveals that sample clusters are dominated by geographic origin (e.g., by city or country), making it impossible to detect the effect of the primary variable you are studying.

Solution:

- Pre-Study Design:

- Stratified Sampling: If comparing two primary groups (e.g., cases vs. controls), ensure that subjects from both groups are recruited from each geographic location. This design balances the geographic confounder across your groups of interest.

- Centralized Processing: Process all samples (from DNA extraction to sequencing) in a single, centralized laboratory using identical lots of reagents to minimize technical batch effects aligned with geography [43].

- Post-Hoc Analysis:

- Statistical Blocking: In your statistical models (e.g., PERMANOVA, linear models), treat "geography" as a blocking or random effect. This partitions the variance associated with location before testing the significance of your primary variable [42].

- Batch Correction: Use bioinformatic tools (e.g., ComBat, ConQuR) to remove unwanted geographic variation, provided you have a sufficient number of samples per site.

Issue 2: Differentiating Cohousing Effects from Underlying Genetic or Dietary Similarity

Problem: Individuals who cohabitate often share genetics (family) and diet, making it difficult to attribute microbiome similarity solely to the cohousing environment.

Solution:

- Enhanced Metadata Collection: Design detailed questionnaires to capture diet, family relationships, and the duration of cohabitation [41].

- Targeted Study Design: Recruit study populations that can help disentangle these effects. For example, studying couples (shared environment, different genetics) or roommates (shared environment, different genetics and often diet) provides a clearer signal of pure environmental transmission [41].

- Advanced Statistical Modeling: Use multivariate models that can include diet, genetics, and cohousing status as simultaneous predictors. The residual effect of cohousing after accounting for diet and genetics can be attributed to the shared environment [42]. Longitudinal sampling at the start of cohabitation and over time is the most powerful way to track microbial exchange.

Issue 3: Controlling for Pet Ownership in a Cohort with Diverse Animals

Problem: Participants own a variety of pets (dogs, cats, birds, reptiles) with potentially different impacts on the human microbiome, making it difficult to create a simple "pet ownership" variable.

Solution:

- Granular Data Collection: Do not use a simple "yes/no" for pet ownership. Create a detailed questionnaire that captures:

- Species and number of each animal.

- Indoor vs. outdoor status of the pet.

- Level of contact (e.g., sleeps on bed, licks face, rarely touched).

- Create Composite Variables: For analysis, you can create multiple variables. One approach is to create a separate variable for each common pet type (e.g., dog ownership, cat ownership). Another is to create a composite "intensity of contact" score that factors in the number of pets, their access to the home, and interaction frequency with the participant [41].

Issue 4: High Unexplained Variance in Models Despite Including Key Environmental Covariates

Problem: Even after including variables for geography, cohousing, and pets, a large amount of variance in your microbiome data remains unexplained.

Solution:

- Check for Unexplained Batch Effects: Re-examine your laboratory metadata (e.g., DNA extraction date, sequencing run) to see if technical batches align with the residual variance. If so, include these as additional covariates [43].

- Consider Other Major Drivers: The biggest factors influencing the gut microbiome are often diet and medication use, especially antibiotics. Ensure you have collected and included high-quality data on these factors. As highlighted at the GMFH Summit, detailed dietary assessment is crucial as many non-nutritive compounds (e.g., emulsifiers, phytochemicals) can impact the microbiome but are often unmeasured [41].

- Increase Sample Size: Unexplained variance can simply be due to the high intrinsic individuality of microbiomes. Larger sample sizes provide the statistical power to detect weaker, but still significant, effects [45].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Standardized Protocol for Environmental Variable Assessment

Adhering to a rigorous protocol is essential for generating comparable and reliable data. The workflow below outlines the key stages for controlling environmental variables.

Diagram Title: Environmental Confounder Control Workflow

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and their functions for ensuring data quality in studies assessing environmental variables.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Study | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Standardized Sample Kits | Ensures consistent sample collection, preservation, and initial storage across all participants and geographic locations [46]. | Kits should be validated to prevent microbial growth or composition shifts during storage and transport [43]. |

| DNA Extraction Kit | To lyse microbial cells and extract total DNA for sequencing. Using a single kit/lot is vital for cross-site comparisons [47]. | Performance should be tested across sample types; some kits are optimized for low-biomass samples [44]. |

| Mock Microbial Community | A defined mix of known microorganisms used as a positive control. It assesses DNA extraction efficiency, PCR bias, and sequencing accuracy [43]. | Should be included in every processing batch to monitor technical variability. |

| Negative Control Reagents | Sterile water or buffer taken through the entire DNA extraction and sequencing process. Identifies contaminants from reagents and the laboratory environment [44]. | Essential for low-biomass studies. Its microbial profile should be subtracted from real samples. |