Controlling False Discoveries in Microbiome Studies: A Comprehensive Guide to FDR Methods for Robust Differential Abundance Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive guide to false discovery rate (FDR) control methods in microbiome differential abundance analysis for researchers and drug development professionals.

Controlling False Discoveries in Microbiome Studies: A Comprehensive Guide to FDR Methods for Robust Differential Abundance Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to false discovery rate (FDR) control methods in microbiome differential abundance analysis for researchers and drug development professionals. We explore the fundamental statistical challenges posed by compositional data, zero-inflation, and sparsity that complicate FDR control. The review systematically compares modern FDR methodologies including ANCOM-BC2, DS-FDR, and massMap, evaluating their performance across diverse datasets. Practical implementation strategies and normalization techniques are discussed to optimize analysis workflows. Validation frameworks and comparative benchmarks provide evidence-based recommendations for selecting appropriate methods. This synthesis enables researchers to implement robust statistical practices that improve reproducibility and reliability in microbiome biomarker discovery.

The Fundamental Challenge: Why Microbiome Data Poses Unique Obstacles for False Discovery Rate Control

Understanding the Compositional Nature of Microbiome Data and Its Impact on FDR

High-throughput sequencing technologies have revolutionized microbiome research by enabling comprehensive profiling of microbial communities. However, a fundamental characteristic of the resulting data presents a substantial statistical challenge: compositionality [1]. Microbiome datasets are compositional because sequencing instruments deliver a fixed number of reads, meaning the total count per sample is arbitrary and contains no biological information. Consequently, the data represent relative abundances (proportions) rather than absolute counts, where an increase in one taxon's abundance necessarily leads to apparent decreases in others due to the fixed total constraint [1]. This property invalidates the core assumption of independence between features in standard statistical methods and, if unaddressed, leads to spurious correlations and severely inflated false discovery rates (FDR) in differential abundance testing [2] [1].

The field lacks consensus on optimal differential abundance analysis (DAA) methods, with different tools often producing discordant results when applied to the same dataset [3] [2]. This guide provides an objective comparison of current methodological approaches, evaluates their performance in controlling FDR, and outlines established and emerging best practices for robust microbiome analysis.

Methodological Approaches for Compositional Data

Statistical methods for differential abundance testing can be broadly categorized based on how they handle compositionality and other data characteristics like zero-inflation and overdispersion.

Compositional Data Analysis (CoDA) Methods

These methods explicitly acknowledge the compositional nature of the data by analyzing log-ratios between taxa, thereby transforming the data from the constrained simplex space to real space where standard statistical methods can be applied [3] [1].

- ALDEx2: Uses a centered log-ratio (CLR) transformation, where taxon counts are divided by the geometric mean of all taxa within a sample [3] [4]. Recent advancements incorporate scale models as a generalization of normalizations to account for uncertainty in biological system scale, drastically reducing false positives compared to standard normalizations [4].

- ANCOM(-BC): Employs an additive log-ratio (ALR) transformation, using a single taxon (or a consensus) present with low variance across samples as the reference denominator for ratios [3]. ANCOM-BC further includes bias correction terms.

- PhILR: Implements an isometric log-ratio (ILR) transformation guided by a phylogenetic tree, creating balances between phylogenetically related groups of taxa [5].

Normalization-Based Methods

These methods calculate a "size factor" or "normalization factor" from the count data to standardize samples to a common scale, and then apply standard statistical models. They often rely on the assumption that most taxa are not differentially abundant [6] [2].

- DESeq2 and edgeR: Popular methods adapted from RNA-Seq analysis that use negative binomial models. They employ robust normalization techniques like Relative Log Expression (RLE) and Trimmed Mean of M-values (TMM), respectively [3] [2].

- MetagenomeSeq: Uses a zero-inflated Gaussian (ZIG) model and Cumulative Sum Scaling (CSS) normalization to account for both compositionality and zero inflation [3] [6].

- Group-Wise Normalizations: Emerging approaches like Group-Wise RLE (G-RLE) and Fold-Truncated Sum Scaling (FTSS) reconceptualize normalization as a group-level rather than sample-level task, showing improved FDR control in challenging scenarios [6].

Non-Parametric and Machine Learning Approaches

Some approaches bypass specific distributional assumptions.

- Traditional Tests: Methods like the Wilcoxon rank-sum test and t-test are sometimes applied to CLR-transformed or proportion-normalized data [3] [7].

- Machine Learning: For predictive tasks, some studies have found that simpler, proportion-based normalizations (e.g., Hellinger transformation) can outperform complex compositional transformations when used with algorithms like random forests [5].

Table 1: Summary of Differential Abundance Method Categories and Their Characteristics

| Category | Representative Methods | Core Approach | Key Assumptions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compositional (CoDA) | ALDEx2, ANCOM-BC, PhILR | Log-ratio transformations (CLR, ALR, ILR) | Data is relative; log-ratios are valid for inference |

| Normalization-Based | DESeq2, edgeR, metagenomeSeq | Size factor estimation & count modeling | Most features are non-differential; normalization corrects for compositionality |

| Non-Parametric / ML | Wilcoxon test (on CLR), Random Forests | Rank-based or algorithmic analysis | Data structure is learnable without specific distributions |

Performance Comparison: FDR Control and Power

Comprehensive benchmarking studies reveal that the choice of DAA method significantly impacts the number and identity of taxa identified as significant, influencing biological interpretations.

Consistency and False Discovery Rate Control

A large-scale evaluation of 14 DAA tools across 38 datasets found that methods produced "drastically different numbers and sets of significant" taxa [3]. The number of features identified often correlated with dataset characteristics like sample size and sequencing depth, rather than biological truth alone [3].

- Robust FDR Control: Methods explicitly addressing compositionality, including ALDEx2, ANCOM-BC, metagenomeSeq (fitFeatureModel), and DACOMP, generally demonstrate improved false-positive control [2].

- Variable Performance: A 2024 benchmark using a realistic signal implantation framework found that only classic methods (linear models, Wilcoxon test, t-test), limma, and fastANCOM properly controlled false discoveries while maintaining relatively high sensitivity. Many other methods exhibited unacceptable FDR inflation [7].

- Impact of Confounding: When confounding variables (e.g., medication, diet) are present, FDR control issues are exacerbated. However, methods that allow for covariate adjustment can effectively mitigate this problem [7].

Statistical Power and Sensitivity

While FDR control is paramount, a method's ability to detect true positives is also critical.

- Power Limitations: Some robust methods like ALDEx2 have been noted to have comparatively low statistical power [2] [3].

- High-Power Methods: The LDM method generally achieves high power, but its FDR control can be unsatisfactory in the presence of strong compositional effects [2].

- Consensus Approach: Given the trade-offs, no single method is simultaneously optimal across all datasets and settings. Using a consensus approach based on multiple DAA methods is recommended to ensure robust biological interpretations [3] [2].

Table 2: Performance Overview of Selected Differential Abundance Methods

| Method | FDR Control | Relative Power | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALDEx2 (with scale models) | Excellent [4] | Moderate | Explicit compositionality handling; accounts for scale uncertainty | Can be conservative; lower power in some settings [3] |

| ANCOM-BC | Good [2] | Moderate to High | Strong compositional theory; good overall performance | Complex output; requires careful interpretation |

| DESeq2 / edgeR | Variable (can inflate) [3] [7] | High | Familiar framework; high power when assumptions hold | Poor FDR control under strong compositionality [3] |

| Limma (voom) | Good (in recent benchmarks) [7] | High | Handles complex designs; good sensitivity | Requires careful normalization |

| Wilcoxon (on CLR) | Good (in recent benchmarks) [7] | Moderate | Simple; non-parametric | Does not model complex covariate structures |

| ZicoSeq | Good [2] | High | Designed for diverse settings; robust | Newer method; less established in some fields |

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

To ensure benchmarking conclusions are biologically relevant, the simulation framework must accurately replicate the properties of real microbiome data.

Realistic Signal Implantation Framework

Traditional parametric simulations often fail to recreate key characteristics of real data, undermining benchmarking conclusions [7]. A robust alternative is signal implantation into real taxonomic profiles:

- Baseline Data Selection: A real dataset from a homogeneous population of healthy individuals serves as the baseline (e.g., the Zeevi WGS dataset) [7].

- Group Assignment: Samples are randomly assigned to two groups (e.g., case vs. control).

- Signal Implantation: A known differential abundance signal is implanted into a small number of pre-selected features in one group using:

- Validation: The simulated data is validated to ensure it retains the feature variance distributions, sparsity, and mean-variance relationships of the original real data. Implanted effect sizes should be calibrated to match those observed in real disease studies (e.g., colorectal cancer, Crohn's disease) [7].

This implantation approach preserves the complex correlation structures and distributional properties of real microbiome data while providing a known ground truth for performance evaluation [7].

Workflow for Method Evaluation

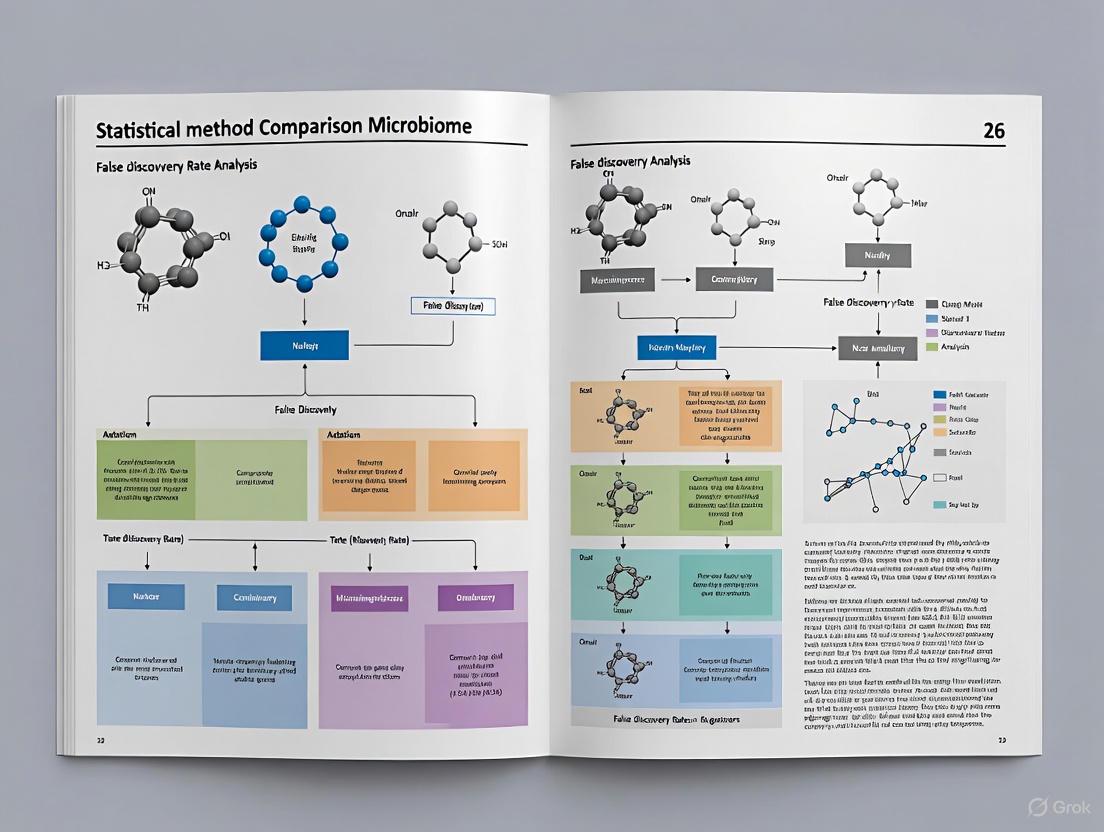

The following diagram illustrates the key steps in a robust benchmarking experiment.

Diagram 1: Benchmarking workflow for evaluating DAA methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Computational Solutions

Successful differential abundance analysis requires a combination of statistical tools, computational resources, and careful experimental design.

Table 3: Essential Tools and Resources for Microbiome Differential Abundance Analysis

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALDEx2 | R Package | CoDA-based DA testing | Use with scale models for improved FDR control [4] |

| ANCOM-BC | R Package | CoDA-based DA testing | Good balance of FDR control and power; handles complex designs [2] |

| DESeq2 / edgeR | R Package | Normalization-based DA testing | Monitor for FDR inflation; powerful but use cautiously [3] [7] |

| ZicoSeq | R Package | General-purpose DA testing | Designed as an optimized, robust procedure for diverse settings [2] |

| PhILR | R Package | ILR Transformation | Transforms data into balances for downstream analysis; requires a phylogenetic tree [5] |

| qPCR / Flow Cytometry | Wet Lab | Absolute Microbial Load | Provides external measurement of biological scale to resolve compositionality [4] |

| Signal Implantation Code | Computational | Method Benchmarking | Enables realistic performance evaluation with known ground truth [7] |

The compositional nature of microbiome sequencing data is not an optional consideration—it is a fundamental property that dictates valid statistical inference [1]. Ignoring compositionality leads to spurious findings and inflated false discovery rates, contributing to reproducibility issues in microbiome research.

Based on current evidence, the following practices are recommended:

- Explicitly Address Compositionality: Prioritize methods that explicitly model the data as compositions (e.g., ALDEx2, ANCOM-BC) or have demonstrated robust FDR control in realistic benchmarks (e.g., limma, classic tests on appropriately transformed data) [2] [7].

- Employ a Consensus Approach: Given that no single method is optimal in all scenarios, use multiple DAA methods and rely on features identified by a consensus to increase confidence in biological interpretations [3].

- Account for Confounders: Always adjust for known technical and biological confounders (e.g., sequencing batch, medication, age) in the DAA model to prevent spurious associations [7].

- Validate with Realistic Benchmarks: When developing new methods or applying existing ones to novel data types, validate performance using realistic simulation frameworks like signal implantation rather than purely parametric simulations [7].

No DAA method can be applied blindly to every dataset. Robust biomarker discovery requires an understanding of the compositional challenge, careful method selection, and transparent reporting of analytical workflows.

The Problem of Zero-Inflation and Sparsity in Microbial Count Data

Microbiome sequencing data, derived from either 16S rRNA gene amplicon or whole-genome shotgun metagenomic approaches, are fundamentally characterized by excessive zeros and high sparsity, with zero-inflation reaching up to 90% in some datasets [8]. These zeros originate from multiple sources: biological zeros (genuine absence of taxa in certain samples), sampling zeros (taxa present but undetected due to limited sequencing depth), and technical zeros (methodological biases from DNA extraction or PCR amplification) [8] [9]. This inherent data characteristic poses substantial challenges for downstream statistical analyses, particularly for methods requiring log-transformation, and can lead to inaccurate feature identification and biased biological interpretations if not properly addressed [9] [10].

The compositional nature of microbiome data—where sequencing only provides information on relative abundances rather than absolute counts—further complicates analysis. When standard methods intended for absolute abundances are applied to relative data, they frequently produce false inferences and spurious results [3]. The combination of zero-inflation, sparsity, and compositionality creates a perfect storm of analytical challenges that necessitate specialized statistical approaches for differential abundance testing and other common microbiome analysis tasks.

Methodological Approaches and Solutions

Differential Abundance Testing Methods

Differential abundance (DA) testing methods aim to identify taxa that significantly differ in abundance between sample groups (e.g., disease vs. control). These methods can be broadly categorized into three groups: classical statistical methods, methods adapted from RNA-Seq analysis, and methods developed specifically for microbiome data [10]. A comprehensive evaluation of 14 DA methods across 38 datasets revealed that these tools identify drastically different numbers and sets of significant taxa, with results highly dependent on data pre-processing decisions [3].

The performance of these methods varies considerably in their ability to control false discovery rates (FDR) while maintaining sensitivity. Methods specifically designed for compositional data, such as ALDEx2 and ANCOM-II, generally produce more consistent results across studies and show better agreement with consensus approaches [3]. ALDEx2 implements a centered log-ratio (CLR) transformation that uses the geometric mean of all taxa within a sample as a reference, while ANCOM uses an additive log-ratio transformation with a single reference taxon [3].

More recent benchmarking studies using realistic simulation frameworks have demonstrated that only classic statistical methods (linear models, Wilcoxon test, t-test), limma, and fastANCOM properly control false discoveries while maintaining relatively high sensitivity [10]. The performance issues are exacerbated when confounding factors (e.g., medication, diet, batch effects) are present, though covariate-adjusted differential abundance testing can effectively mitigate these problems [10].

Zero Imputation Techniques

Zero imputation methods specifically address data sparsity by distinguishing biological zeros from technical zeros and attempting to recover the latter. These methods can be categorized into several approaches:

Probabilistic modeling frameworks like BMDD (BiModal Dirichlet Distribution) capture the bimodal abundance distribution of taxa via a mixture of Dirichlet priors, using variational inference and expectation-maximization algorithms for efficient imputation [9]. Unlike methods that assume unimodal abundance distributions, BMDD can model taxa that exhibit different abundance patterns across conditions, providing more accurate imputation, especially for case-control designs [9].

Deep learning approaches such as mbSparse leverage autoencoder-based architectures, specifically using a feature autoencoder for learning sample representations and a conditional variational autoencoder (CVAE) for data reconstruction [8]. This method integrates insights from sample correlation graphs and reconstructed data to impute zero values, demonstrating superior performance in recovering true abundances.

Other specialized methods include mbImpute, which uses a Gamma-normal mixture model to borrow information from similar samples and taxa, and mbDenoise, which employs zero-inflated probabilistic principal component analysis with variational approximation algorithms [8].

Dimension Reduction Strategies

Dimension reduction techniques help address the high-dimensionality of microbiome data while accounting for its unique characteristics. The zero-inflated Poisson factor analysis (ZIPFA) model properly models original absolute abundance count data while specifically accommodating excessive zeros through a realistic link between true zero probability and Poisson rate [11]. This approach assumes read counts follow zero-inflated Poisson distributions with library size as offset and develops an efficient expectation-maximization algorithm for parameter estimation [11].

Performance Comparison of Methodological Approaches

Differential Abundance Method Performance

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Differential Abundance Testing Methods

| Method | Category | False Discovery Rate Control | Sensitivity | Consistency Across Studies | Handling of Confounders |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALDEx2 | Compositional | Good | Moderate | High | Limited |

| ANCOM-II | Compositional | Good | Moderate | High | Limited |

| limma | RNA-Seq adapted | Good | High | Moderate | Good |

| Wilcoxon test | Classical | Good | Variable | Moderate | With adjustments |

| edgeR | RNA-Seq adapted | Variable (can be high) | High | Low | Moderate |

| LEfSe | Microbiome-specific | Variable | Variable | Low | Limited |

| DESeq2 | RNA-Seq adapted | Variable | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

Evaluation of 14 DA methods across 38 datasets with 9,405 samples revealed that the percentage of significant features identified varied widely, with means ranging from 0.8% to 40.5% depending on the method and filtering approach [3]. Methods such as limma voom and Wilcoxon test with CLR transformation tended to identify the largest number of significant features, though this does not necessarily indicate better performance, as it may reflect higher false positive rates [3].

Realistic benchmarking using signal implantation into real taxonomic profiles has demonstrated that many popular DA methods fail to properly control false positives, particularly when confounding factors are present [10]. In confounded scenarios, only methods that allow for covariate adjustment effectively maintain type I error control while detecting true positive signals.

Zero Imputation Method Performance

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Zero Imputation Methods

| Method | Approach | Accuracy (MSE) | Impact on Downstream Analysis | Handling of Different Zero Types | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMDD | Probabilistic (Bimodal) | Highest | Improves DA analysis | Distinguishes biological/technical zeros | Moderate |

| mbSparse | Deep Learning (Autoencoder) | High (up to 4.1× MSE reduction) | Increases validated disease-associated taxa detection | Recovers >88% of removed counts | Moderate to High |

| mbImpute | Mixture Model | Moderate | Moderate improvement | Uses similar samples/taxa information | High |

| mbDenoise | Probabilistic PCA | Moderate | Some improvement | Zero-inflated probabilistic PCA | High |

| Pseudocount | Naive | Low | Can introduce biases | Does not distinguish zero types | Very High |

In comprehensive evaluations, BMDD outperformed competing methods in reconstructing true abundances across 15 different distance metrics, demonstrating particular strength in capturing the bimodal distribution patterns common in real microbiome data [9]. Similarly, mbSparse achieved mean squared error reductions of up to 4.1 compared to existing microbiome methods, even amid outlier samples and varying sequencing depths [8].

The practical impact of these improved imputation methods on biological discovery is substantial. In colorectal cancer analysis, mbSparse increased the detection of validated disease-associated taxa from 7 to 27, while predictive accuracy improved significantly (area under the precision-recall curve values rising from 0.85 to 0.93) [8].

Experimental Protocols and Validation Frameworks

Realistic Simulation Frameworks for Method Evaluation

Accurate evaluation of methodological performance requires simulation frameworks that faithfully reproduce the characteristics of real microbiome data. Traditional parametric simulation approaches have been shown to generate data that is readily distinguishable from real experimental data by machine learning classifiers, undermining their utility for benchmarking [10].

The signal implantation approach implants calibrated signals into real taxonomic profiles with pre-defined effect sizes, creating a known ground truth while preserving the inherent characteristics of real data [10]. This method can simulate both abundance shifts (by multiplying counts in one group with a constant factor) and prevalence shifts (by shuffling non-zero entries across groups), mimicking the effect patterns observed in real disease studies [10].

Table 3: Key Experimental Considerations for Microbiome Method Validation

| Aspect | Recommendation | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation Approach | Signal implantation into real data | Preserves natural data structure and characteristics |

| Effect Types | Include both abundance and prevalence shifts | Mirrors real biological patterns observed in disease studies |

| Effect Sizes | Scale factors <10 for abundance shifts | Corresponds to effects observed in real associations (e.g., CRC, Crohn's) |

| Confounding Assessment | Include covariate effects with realistic magnitudes | Accounts for known confounders (medication, diet, technical batch effects) |

| Performance Metrics | Both FDR control and sensitivity | Balanced view of method performance |

Validation in Real Data Applications

Robust method evaluation requires validation in real datasets with established biological truths. For example, methods can be tested on diseases with well-characterized microbiome alterations such as colorectal cancer (CRC) or Crohn's disease (CD), where specific microbial signatures have been consistently replicated [10]. Performance assessment should include both the detection of established associations and the control of false discoveries in null scenarios where no true differences exist.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for Microbiome Data Analysis

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Features | Applicable Data Types |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMDD | Zero imputation | Bimodal Dirichlet distribution; Variational inference | 16S, WGS |

| mbSparse | Zero imputation | Autoencoder and CVAE; Sample correlation graphs | 16S, WGS |

| ALDEx2 | Differential abundance | Compositional data analysis; CLR transformation | 16S, WGS |

| ANCOM-II | Differential abundance | Compositional data analysis; Additive log-ratio | 16S, WGS |

| limma | Differential abundance | Linear models with empirical Bayes moderation | 16S, WGS, RNA-Seq |

| ZIPFA | Dimension reduction | Zero-inflated Poisson factor analysis | 16S, WGS |

| QIIME 2 | Pipeline | End-to-end analysis platform | Primarily 16S |

| MetaPhlAn | Taxonomic profiling | Marker gene-based taxonomic assignment | Primarily WGS |

Integrated Analysis Workflows

The complex interplay between zero-inflation, compositionality, and high-dimensionality necessitates integrated analytical workflows that appropriately address these characteristics at each step. The following diagram illustrates a recommended workflow for microbiome data analysis that properly accounts for data sparsity and compositionality:

Microbiome Data Analysis Workflow: An integrated approach addressing data sparsity and compositionality.

The problems of zero-inflation and sparsity in microbial count data present significant challenges that require specialized methodological approaches. Current evidence suggests that no single method universally outperforms all others across all scenarios, highlighting the value of consensus approaches that combine multiple complementary techniques [3].

For differential abundance testing, compositional methods like ALDEx2 and ANCOM-II generally provide more consistent results, while covariate-adjusted implementations of classical methods often show the best balance of false discovery control and sensitivity, particularly in the presence of confounding factors [10]. For zero imputation, newer probabilistic and deep learning approaches like BMDD and mbSparse demonstrate superior performance in recovering true abundances and improving downstream analysis results [8] [9].

Future methodological development should focus on integrative approaches that simultaneously address zero-inflation, compositionality, and confounding, as well as scalable implementations capable of handling the increasingly large and complex microbiome datasets being generated. Furthermore, the establishment of standardized benchmarking frameworks using biologically realistic simulations will be crucial for objectively evaluating new methods and translating methodological advances into robust biological insights.

In microbiome research, high-throughput sequencing technologies enable the profiling of hundreds to thousands of microbial taxa, metabolites, or genetic variants simultaneously. This generates a fundamental statistical challenge: the multiple testing burden. When dozens to thousands of hypotheses are tested simultaneously, the probability of falsely declaring statistically significant findings increases dramatically [12]. This problem is particularly acute in microbiome studies, where features are highly interdependent and data exhibit complex properties like compositionality, sparsity, and over-dispersion [3] [13] [14]. The multiple testing burden poses a critical threat to the reproducibility of microbiome research, as false discoveries can lead to erroneous biological interpretations and misguided follow-up studies [10].

The statistical foundation of this problem lies in the definition of the p-value. A conventional p-value threshold of α = 0.05 implies a 5% probability of false positives for a single test. However, with m independent tests, the probability of at least one false positive rises to 1 - (1-α)^m. For 1,000 tests, this probability exceeds 99% [12]. This phenomenon directly impacts the false discovery rate (FDR)—the expected proportion of false positives among all significant findings—which can become unacceptably high without proper statistical correction [15] [10].

Quantitative Comparison of Method Performance

Microbiome differential abundance (DA) testing methods employ distinct strategies to handle multiple testing burdens while controlling error rates. The performance of these methods varies significantly in their sensitivity to detect true positives and their ability to control false positives.

Table 1: Key Differential Abundance Methods and Their Multiple Testing Approaches

| Method | Statistical Approach | Multiple Testing Correction | Data Types |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALDEx2 | Compositional, Monte Carlo | Benjamini-Hochberg FDR | 16S, Metagenomics |

| ANCOM | Compositional, log-ratio | W-statistic ranking | 16S, Metagenomics |

| DESeq2 | Negative binomial model | Benjamini-Hochberg FDR | RNA-Seq, Metagenomics |

| edgeR | Negative binomial model | Benjamini-Hochberg FDR | RNA-Seq, Metagenomics |

| LEfSe | Linear discriminant analysis | Step-wise FDR control | 16S, Metagenomics |

| limma-voom | Linear models with precision weights | Benjamini-Hochberg FDR | RNA-Seq, Metagenomics |

| PERMANOVA | Distance-based permutation | Permutation tests | 16S, Metagenomics |

| FFMANOVA/ASCA | Multivariate ANOVA | Rotation/permutation tests | Metagenomics, Metabolomics |

Table 2: Performance Comparison Across Differential Abundance Methods

| Method | Average False Discovery Rate | Sensitivity | Handling of Compositionality | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALDEx2 | Well-controlled [10] | Lower power [3] | Excellent [14] | Conservative analysis |

| ANCOM/ANCOM-BC | Well-controlled [15] [10] | Moderate [3] | Excellent [14] | Compositional data focus |

| DESeq2 | Variable, can be high [10] | High [14] | Moderate with transformations | High-power needs |

| edgeR | Can be high [3] | High [3] | Moderate with transformations | Large effect sizes |

| limma-voom | Generally controlled [10] | High [3] | Moderate with transformations | Large sample sizes |

| Wilcoxon test | Generally controlled [10] | Moderate [10] | Poor without transformation | Non-parametric alternative |

Recent large-scale benchmarking studies reveal substantial variability in how methods control false discoveries. When applied to 38 different 16S rRNA gene datasets, 14 different DA testing approaches identified "drastically different numbers and sets of significant" features [3]. Some methods, like limma-voom and Wilcoxon testing on CLR-transformed data, tended to identify the largest number of significant features, while others, like ALDEx2, produced more conservative results [3]. A separate 2024 benchmark of nineteen DA methods found that only classic statistical methods (linear models, Wilcoxon test, t-test), limma, and fastANCOM properly controlled false discoveries while maintaining relatively high sensitivity [10].

Experimental Protocols for Method Evaluation

Simulation Frameworks for Benchmarking

Establishing realistic benchmarking frameworks is essential for proper evaluation of multiple testing corrections. Earlier parametric simulation approaches often failed to recreate key characteristics of real microbiome data, making benchmarking conclusions unreliable [10]. A 2024 study proposed a signal implantation approach that introduces calibrated effect sizes into real taxonomic profiles, preserving the natural complexity of microbiome data while providing a known ground truth for evaluation [10].

Signal Implantation Protocol:

- Baseline Data Selection: Use real microbiome datasets from healthy populations as baseline (e.g., Zeevi WGS dataset)

- Effect Size Calibration: Implant signals with pre-defined effect sizes mimicking real disease associations:

- Abundance scaling: Multiply counts in one group with a constant factor

- Prevalence shift: Shuffle a percentage of non-zero entries across groups

- Validation: Verify implanted features resemble real-world effect sizes through comparison with established disease biomarkers

This approach preserves feature variance distributions, sparsity patterns, and mean-variance relationships present in real experimental data, addressing critical limitations of purely parametric simulations [10].

Cross-Study Validation Approaches

Independent validation across multiple datasets provides crucial insights into method robustness. One comprehensive evaluation analyzed 9,405 samples across 38 different microbiome datasets representing diverse environments including human gut, marine, soil, and built environments [3]. The evaluation protocol included:

- Concordance Analysis: Measuring agreement between methods on the same datasets

- False Positive Assessment: Artificially subsampling datasets into groups where no differences were expected

- Biological Consistency: Evaluating whether consistent biological interpretations emerged across different methods

This multi-faceted approach revealed that ALDEx2 and ANCOM-II produced the most consistent results across studies and agreed best with the intersect of results from different approaches [3].

Visualization of Method Evaluation Workflows

Benchmarking Workflow for Multiple Testing Methods

Multiple Testing Correction Approaches

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Microbiome Multiple Testing Research

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| R/Bioconductor | Statistical computing environment | Implementation of DA methods |

| QIIME 2 | Microbiome data processing | Pipeline for 16S analysis |

| metaGEENOME R package | Differential abundance analysis | Cross-sectional/longitudinal studies |

| ALDEx2 | Compositional DA analysis | False discovery rate control |

| ANCOM-BC | Bias-corrected compositional analysis | Accounting for sampling fractions |

| DESeq2 | Generalized linear models | High-sensitivity applications |

| limma-voom | Linear models with precision weights | Large-scale studies |

| MicrobiomeDB | Public dataset repository | Method validation |

| SpiecEasi | Network inference | Correlation structure estimation |

| NORtA algorithm | Data simulation | Method benchmarking |

Integrated Analysis Strategies for Robust Discovery

No single method consistently outperforms all others across diverse datasets and research questions. Therefore, consensus approaches that integrate results from multiple complementary methods provide more robust biological interpretations [3]. For example, one strategy employs ALDEx2 or ANCOM-II as a conservative baseline, complemented by more sensitive methods like DESeq2 or limma-voom for features showing consistent signals across approaches [3].

In genome-wide association studies, the multiple testing burden is even more extreme, with an estimated one million independent tests genomewide in European populations [16]. This has led to the development of specialized methods like DeepRVAT that integrate diverse variant annotations using deep set networks to improve power while controlling for false discoveries [17]. This approach demonstrates how leveraging rich biological annotations can mitigate multiple testing burdens by prioritizing likely functional variants.

The integration of microbiome data with metabolomic profiles introduces additional multiple testing challenges. A comprehensive benchmark of nineteen integrative methods for microbiome-metabolome data identified distinct best-performing methods for different research goals: MMiRKAT for global associations, sPLS and sCCA for data summarization, and SparseLVMs for feature selection [13]. This highlights the importance of matching analytical strategies to specific research questions rather than seeking a universal solution.

The multiple testing burden from dozens to thousands of simultaneous hypotheses remains a fundamental challenge in microbiome research. Method performance varies substantially, with trade-offs between sensitivity and false discovery control. Consensus approaches that integrate multiple complementary methods, coupled with appropriate simulation-based benchmarking, provide the most reliable path to robust biological discovery. As methodological development continues, researchers must prioritize biological realism in evaluation frameworks and transparent reporting of analytical choices to enhance reproducibility in microbiome science.

A fundamental goal in microbiome research is to identify microorganisms whose abundances differ between conditions, such as health versus disease. This process, known as differential abundance (DA) analysis, faces two significant statistical challenges that can inflate false discovery rates (FDR): the compositional nature of the data and the complex dependence structures between microbial taxa. Microbiome data are compositional because sequencing instruments measure relative abundances rather than absolute counts; the increase of one taxon necessarily leads to the apparent decrease of others due to the fixed total count constraint [18] [3]. This property induces spurious correlations that violate the assumptions of standard statistical tests. Simultaneously, biological interactions and technical artifacts create intricate dependence structures that, if ignored, further compromise FDR control [19] [20]. Numerous method comparisons have demonstrated that these factors cause popular DA methods to produce alarmingly high false positive rates, raising doubts about the reproducibility of microbiome discoveries [3] [21]. This guide objectively compares the performance of leading statistical methods under these challenges, providing experimental data and protocols to inform method selection for robust microbiome science.

Method Performance Under Compositional Bias and Dependence

Quantitative Comparison of Differential Abundance Methods

Table 1: Performance of Differential Abundance Methods Across 38 Datasets

| Method | Approach | Average FDR Control | Sensitivity to Dependence | Compositional Bias Correction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOCOM | Logistic regression on compositions | Robust [19] | Robust to taxon-taxon interactions [19] | Full (uses taxon ratios) [19] |

| ALDEx2 | Compositional (CLR transformation) | Robust [3] | Moderate | Full [3] |

| ANCOM-II | Compositional (log-ratio) | Robust [3] | Moderate | Full [3] |

| coda4microbiome | Penalized log-ratio regression | N/A | N/A | Full [18] |

| LEfSe | Linear Discriminant Analysis | Poor (high FDR) [3] | High | Partial (often requires rarefaction) [3] |

| edgeR | Negative binomial model | Poor (high FDR) [3] | High | None (requires normalization) [3] |

| DESeq2 | Negative binomial model | Variable [3] | High | None (requires normalization) [3] |

| limma voom | Linear models with precision weights | Poor (high FDR) [3] | High | Partial [3] |

| Wilcoxon test | Non-parametric test | Poor (high FDR) [3] | High | None (often used on CLR) [3] |

Table 2: Impact of Experimental Bias on Compositional Methods

| Bias Type | Impact on FDR | LOCOM Performance | Other Methods Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main effect bias (DNA extraction, PCR amplification) | Moderate inflation | Robust (FDR controlled) [19] | Inflated FDR for most methods [19] |

| Taxon-taxon interaction bias | Severe inflation | Remains robust to reasonable range [19] | Further FDR inflation beyond main effects [19] |

| Library size variation | Severe inflation | Robust (compositional) [19] | Variable; often severe inflation without normalization [3] |

| Zero-inflation | Moderate inflation | N/A | Varies by method; some methods handle well [22] |

Experimental Evidence on FDR Inflation

Large-scale benchmarking studies reveal alarming FDR inflation across many popular methods. A comprehensive evaluation of 14 DA tools across 38 microbiome datasets (9,405 total samples) found drastic differences in the number and sets of significant taxa identified by each method [3]. Methods like limma voom (TMMwsp) identified up to 40.5% of taxa as significant on average, while other tools found as few as 0.8%, highlighting the lack of consensus and potential for spurious findings. This study also demonstrated that some tools, particularly ALDEx2 and ANCOM-II, produce more consistent results across studies and best approximate the consensus of different approaches [3].

The problem extends beyond theoretical concerns. One benchmarking paper titled "A broken promise: microbiome differential abundance methods do not control the false discovery rate" concluded through extensive parametric and nonparametric simulation that most methods exhibit an "alarming excess of false discoveries," imperiling the reproducibility of microbiome experiments [21]. This study particularly highlighted that ignoring the correlation between species, a common simplification in simulation studies, negatively affects method performance and FDR control.

Experimental Protocols for Method Evaluation

Simulation Framework for Testing FDR Control

Table 3: Key Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

| Protocol Component | Description | Purpose | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Null Dataset Simulation | Shuffling case-control labels or simulating data with no true differences | Empirical FDR calculation | Number of permutations, sample size, sparsity level |

| Spike-in Simulation | Artificially introducing abundance changes for specific taxa | Power and true positive rate assessment | Effect size, number of spiked taxa, baseline composition |

| Correlation Structure Simulation | Generating data with prescribed taxon-taxon dependencies | Dependence impact evaluation | Correlation strength, network structure, cluster size |

| Compositional Bias Simulation | Inducing library size variation and compositional effects | Bias sensitivity assessment | Fold-change in library sizes, zero inflation proportion |

| Real Data Resampling | Bootstrapping or subsampling from existing datasets | Real-world performance evaluation | Resampling proportion, number of iterations |

Detailed Protocol for Null Simulation Analysis:

- Data Generation: Create multiple datasets with no true differential abundance between groups. This can be achieved by randomly shuffling case-control labels in real data or simulating data where all samples come from the same underlying distribution [21].

- Method Application: Apply each DA method to these null datasets using standard preprocessing steps (e.g., prevalence filtering, normalization if required).

- FDR Calculation: For each method, compute the proportion of null datasets where any taxa are falsely identified as significant. Under the null, the expected FDR should be at or below the nominal level (e.g., 5%).

- Iteration: Repeat the process across multiple simulated datasets (typically 100-1000 iterations) to obtain stable FDR estimates.

Detailed Protocol for Power Simulation:

- Baseline Data Generation: Simulate baseline microbiome data using realistic distributions (e.g., negative binomial, Dirichlet-multinomial) that capture the overdispersion and sparsity of real data [21].

- Spike-in Signal: Select a predefined set of taxa (typically 5-20%) and introduce abundance changes between groups with specified effect sizes (fold-changes typically ranging from 1.5 to 4).

- Method Application and Evaluation: Apply each DA method and compute sensitivity (proportion of truly differential taxa that are detected) and precision (proportion of significant findings that are truly differential).

- Correlation Introduction: Incorporate realistic taxon-taxon correlation structures either estimated from real data or generated from predefined covariance matrices to assess the impact of dependence [21].

Benchmarking Workflow for Method Comparison

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for comprehensive method evaluation:

Experimental Workflow for Method Benchmarking

Visualizing Compositional Bias and Dependence Structures

The Mechanism of Compositional Bias

The diagram below illustrates how compositional bias arises in microbiome data analysis and why it inflates false discovery rates:

Mechanism of Compositional Bias in Microbiome Data

Advanced Normalization Framework

Recent methodological advances address compositional bias through group-wise normalization approaches. The mathematical derivation of compositional bias shows that under a multinomial model, the observed log fold change ((\hat{\alpha}{1j})) converges to the true log fold change ((\beta{1j})) plus a bias term ((\Delta)) that depends on all taxa in the community [22]:

[ \hat{\alpha}{1j} \overset{p}{\rightarrow}\ \beta{1j} + \Delta,\ \text{where}\ \Delta = \log \bigl( \sum{j=1}^q\exp(\beta{0j}) / \sum{j=1}^q\exp(\beta{0j} + \beta_{1j})\bigr) ]

This formal characterization reveals that normalization must account for group-level differences rather than just sample-level characteristics. New methods like Group-Wise Relative Log Expression (G-RLE) and Fold-Truncated Sum Scaling (FTSS) explicitly address this by incorporating group-level summary statistics, achieving better FDR control and higher power than sample-level normalization methods [22].

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Microbiome Differential Abundance Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| coda4microbiome R package [23] [18] | Identification of microbial signatures via penalized log-ratio regression | Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies | Compositional data analysis, balance selection, graphical outputs |

| LOCOM [19] | Differential abundance testing with FDR control | General case-control studies | Robust to experimental bias, handles taxon interactions |

| ALDEx2 [3] | Differential abundance via CLR transformation | General purpose DA analysis | Compositional, robust FDR control |

| ANCOM-II [3] | Differential abundance via additive log-ratio | General purpose DA analysis | Compositional, robust FDR control |

| microbiome R package [24] | Data handling and analysis utilities | Microbiome data preprocessing and exploration | Extends phyloseq, multiple datasets, standardization |

| SIAMCAT [25] | Machine learning for microbiome data | Prediction model development | Multiple normalization options, cross-validation |

| MetagenomeSeq with FTSS [22] | Normalization-based DA analysis | Scenarios with large compositional bias | Group-wise normalization, improved FDR control |

The evidence consistently demonstrates that compositional bias and dependence structures substantially inflate false discovery rates in microbiome differential abundance analysis. Methods that explicitly account for compositionality through log-ratio transformations (e.g., LOCOM, ALDEx2, ANCOM-II, coda4microbiome) generally provide more reliable FDR control than methods designed for non-compositional data or those requiring external normalization [19] [3]. For researchers using normalization-based approaches, newly developed group-wise normalization methods like G-RLE and FTSS offer improved performance over traditional sample-level normalization [22].

Based on the current evidence, we recommend:

- Adopt compositional methods as primary analysis tools rather than standard statistical tests designed for non-compositional data.

- Use a consensus approach combining multiple DA methods to enhance confidence in findings.

- Implement group-wise normalization when using normalization-based methods, particularly in studies with large effect sizes or substantial compositional bias.

- Perform rigorous validation through null simulation studies to verify FDR control in specific experimental contexts.

These practices will enhance the reliability and reproducibility of microbiome discoveries, ultimately strengthening the translation of microbiome research into clinical and therapeutic applications.

In high-throughput microbiome studies, where hundreds to millions of hypotheses are typically tested simultaneously, understanding and controlling for statistical errors is not merely advantageous—it is fundamental to deriving biologically valid conclusions. The unique characteristics of microbiome data, including zero-inflation, overdispersion, high-dimensionality, and compositional nature, pose distinctive challenges that complicate traditional statistical approaches [26] [27]. Within this framework, three statistical concepts emerge as particularly crucial for ensuring research reproducibility: Type I error, False Discovery Rate (FDR), and statistical power. Type I errors represent false positive conclusions, where researchers incorrectly reject a true null hypothesis, while FDR provides a more practical framework for error control in multiple testing scenarios by quantifying the expected proportion of false discoveries among all significant findings [28] [29]. Statistical power, the probability of correctly detecting a true effect, completes this triad by ensuring studies possess adequate sensitivity to detect biologically relevant differences [29] [30]. The proper management of the inherent trade-offs between these three concepts forms the bedrock of reliable microbiome statistical analysis, enabling researchers to navigate the complexities of microbial datasets while minimizing both false positives and false negatives.

Core Conceptual Definitions

Type I Error (False Positive)

A Type I error, often termed a false positive, occurs when a statistical test incorrectly rejects a true null hypothesis [29] [31]. In practical microbiome research terms, this means concluding that a microbial taxon is differentially abundant between experimental groups when, in reality, no such difference exists. The probability of committing a Type I error is denoted by α (alpha) and is typically controlled by setting a significance level, commonly at 0.05 or 5% [29] [31]. This threshold implies a 5% risk of falsely rejecting the null hypothesis when it is true. For microbiome researchers, this translates to the risk of identifying microbial biomarkers that appear statistically significant but actually arose by chance alone, potentially leading to erroneous biological interpretations and follow-up studies based on false premises.

False Discovery Rate (FDR)

The False Discovery Rate (FDR) is a statistical approach that addresses a key limitation of Type I error control in high-dimensional microbiome studies. Whereas traditional Type I error control (e.g., Bonferroni correction) focuses on the probability of making even one false discovery among all tests, FDR controls the expected proportion of false discoveries among all significant tests [28]. This distinction is particularly important in microbiome research where thousands of microbial taxa are tested simultaneously. Modern FDR methods have evolved beyond using only p-values as input; they now incorporate complementary information as informative covariates to prioritize, weight, and group hypotheses, thereby increasing statistical power without sacrificing error control [28]. These advanced techniques have demonstrated modest but consistent power advantages over classic FDR approaches, with performance improvements directly correlated to the informativeness of the incorporated covariates [28].

Statistical Power and Type II Error

Statistical power represents the probability that a test will correctly reject a false null hypothesis, thereby detecting a true effect when one exists [29] [30]. Power is mathematically defined as 1 - β, where β (beta) is the probability of a Type II error (false negative)—failing to reject a false null hypothesis [29]. In microbiome research, a Type II error would occur when an analysis fails to identify a truly differentially abundant microbe. The power of a statistical test in microbiome studies is influenced by several factors: the effect size (magnitude of the difference between groups), sample size, significance level (α), and the specific diversity metrics employed in the analysis [30]. A power level of 80% or higher is generally considered acceptable in biological research, meaning there's only a 20% chance of missing a true effect [29].

Table 1: Relationship Between Statistical Decision and Ground Truth

| Statistical Decision | Null Hypothesis (H₀) True | Null Hypothesis (H₀) False |

|---|---|---|

| Reject H₀ | Type I Error (False Positive) | Correct Inference (True Positive) |

| Fail to Reject H₀ | Correct Inference (True Negative) | Type II Error (False Negative) |

The Interplay Between Concepts: Trade-offs and Relationships

The relationship between Type I error, FDR, and statistical power is characterized by fundamental trade-offs that microbiome researchers must strategically navigate. Reducing the Type I error rate (α) invariably comes at the cost of increasing the Type II error rate (β), thereby decreasing statistical power [29]. This inverse relationship creates a delicate balancing act in study design and data analysis. The crossover error rate (CER) represents the point at which Type I and Type II errors are equal, with systems possessing lower CER values generally providing more classification accuracy [31].

Modern FDR control methods offer one solution to these trade-offs by leveraging complementary information (covariates) to increase power while maintaining controlled error rates [28]. The improvement offered by these modern FDR methods over classic approaches increases with three key factors: the informativeness of the covariate, the total number of hypothesis tests, and the proportion of truly non-null hypotheses [28]. This makes covariate-adjusted FDR methods particularly valuable in large-scale microbiome studies with complex experimental designs.

Diagram 1: Error Trade-off. This diagram illustrates the fundamental trade-off between Type I error (α) and statistical power (1-β) in microbiome studies.

Statistical Frameworks for Microbiome Data Analysis

Multiple Testing Correction Methods

In microbiome studies, where hundreds to millions of microbial taxa are tested simultaneously, multiple testing correction becomes essential to avoid an explosion of false positive results. The False Discovery Rate (FDR) has emerged as a popular and powerful tool for error rate control in this high-dimensional context [28]. Unlike family-wise error rate (FWER) methods that control the probability of at least one false discovery, FDR methods control the expected proportion of false discoveries among all significant tests, providing a more balanced approach for microbiome applications [28].

Modern FDR methods such as Benjamini-Hochberg and covariate-adjusted variants provide a framework for maintaining control over false discoveries while offering greater sensitivity than traditional Bonferroni correction. These methods are particularly valuable in microbiome research due to the correlated nature of microbial data and the availability of informative covariates such as phylogenetic relationships, prevalence patterns, and abundance measures that can enhance statistical power [28].

Power Analysis and Sample Size Calculation

Conducting a priori power analysis is crucial for designing informative microbiome studies that can reliably detect effects of biological interest [32]. The power of a test in microbiome research depends on four interrelated parameters: the effect size (quantification of the outcome of interest), sample size (number of samples collected), power (probability of correctly rejecting a false null hypothesis), and significance level (probability of Type I error) [30].

Tools such as Evident have been developed specifically for microbiome power calculations, enabling researchers to derive effect sizes from large existing databases (e.g., American Gut Project, FINRISK, TEDDY) for various metadata variables and diversity measures [33]. This approach allows for realistic power estimation based on actual microbiome data characteristics rather than theoretical distributions. Evident supports effect size calculations for commonly used microbiome measures including α-diversity, β-diversity, and log-ratio analysis, providing flexibility across different analytical frameworks [33].

Table 2: Common Diversity Metrics and Their Statistical Properties in Microbiome Studies

| Metric Type | Specific Metrics | Statistical Properties | Sensitivity to Group Differences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha Diversity | Observed ASVs, Chao1, Shannon, Phylogenetic Diversity | Summarizes within-sample diversity considering richness and/or evenness | Varies by metric and data structure; generally less sensitive than beta diversity [30] |

| Beta Diversity | Bray-Curtis, Jaccard, Unweighted/Weighted UniFrac | Quantifies between-sample dissimilarity using abundance or presence/absence | Bray-Curtis is generally most sensitive; detects differences with smaller sample sizes [30] |

| Phylogenetic Metrics | Unweighted/Weighted UniFrac, Faith's PD | Incorporates evolutionary relationships between taxa | Suitable for detecting community-level changes; less suitable for small sample sizes [34] |

Experimental Protocols for Method Comparison

Benchmarking Experimental Design

Robust comparison of statistical methods for error control in microbiome research requires carefully designed benchmarking experiments that evaluate method performance across diverse datasets and conditions. An effective benchmarking protocol should incorporate both simulated data with known ground truth and empirical datasets representing different study designs and sample types [34]. For simulation studies, data should be generated to reflect the key characteristics of real microbiome data: zero-inflation, overdispersion, compositionality, and phylogenetic structure [26] [27]. Empirical datasets should represent various research scenarios, including dietary interventions, disease-control comparisons, and longitudinal studies [34].

The benchmarking protocol should evaluate statistical methods based on multiple performance metrics: FDR control (ability to maintain the advertised false discovery rate), sensitivity (proportion of true positives detected), precision (proportion of significant findings that are truly differential), and computational efficiency [28] [34]. For methods incorporating covariate information, evaluation should include assessment of performance gains with increasingly informative covariates [28].

Implementation Workflow for Method Evaluation

Diagram 2: Method Evaluation Workflow. This workflow outlines the key steps in comparing statistical methods for error control in microbiome studies.

The implementation of method comparison studies follows a structured workflow beginning with study design and hypothesis formulation. Researchers must clearly define the research questions and experimental factors to be investigated [34]. Next, data collection and preprocessing involves quality control, filtering of low-abundance taxa, and addressing technical artifacts. The normalization step is critical, as the choice of normalization method (e.g., Total Sum Scaling - TSS, Cumulative Sum Scaling - CSS, Trimmed Mean of M-values - TMM) can significantly impact downstream results [26] [27].

Following normalization, researchers select and implement multiple statistical methods for comparison, ensuring that each method is applied according to its recommended specifications [34]. Performance metrics are then calculated for each method, focusing on FDR control, sensitivity, and precision. The final interpretation phase involves synthesizing results across multiple datasets and simulation scenarios to provide generalized recommendations for method selection based on study characteristics [34].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Key Statistical Tools and Packages for Microbiome Data Analysis

| Tool/Package | Primary Function | FDR Control Capabilities | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Evident | Effect size and power calculation | N/A | Power analysis for study design; computes effect sizes for α-diversity, β-diversity, and log-ratios [33] |

| DESeq2 | Differential abundance analysis | Benjamini-Hochberg FDR | RNA-seq and microbiome count data; uses negative binomial distribution [27] [34] |

| ALDEx2 | Differential abundance analysis | Benjamini-Hochberg FDR | Compositional data analysis; uses Dirichlet-multinomial distribution and log-ratio transformation [34] |

| ANCOM | Differential abundance analysis | Implements FDR correction | Specifically addresses compositional nature of microbiome data [34] |

| PERMANOVA | Community-level difference testing | N/A (community-level test) | Multivariate analysis based on distance matrices; tests overall community differences [30] [34] |

| edgeR | Differential abundance analysis | Benjamini-Hochberg FDR | RNA-seq and microbiome count data; uses negative binomial models [27] |

Based on current methodological research and benchmarking studies, several best practices emerge for controlling false discoveries and maintaining statistical power in microbiome studies. First, modern FDR methods that incorporate informative covariates generally provide advantages over classic FDR-controlling procedures, with performance gains dependent on both the application context and the informativeness of available covariates [28]. Second, researchers should select diversity metrics aligned with their biological questions, recognizing that beta diversity metrics (particularly Bray-Curtis) are generally more sensitive to group differences than alpha diversity metrics, potentially requiring smaller sample sizes for equivalent power [30].

Third, conducting a priori power analysis using tools like Evident with effect sizes derived from large existing datasets can significantly improve study design and resource allocation [33] [32]. Finally, to protect against p-hacking and selective reporting, researchers should publish statistical analysis plans prior to conducting experiments, specifying primary outcomes, diversity metrics, and FDR control methods in advance [30]. By implementing these practices while understanding the fundamental trade-offs between Type I error, FDR, and statistical power, microbiome researchers can enhance the reproducibility, reliability, and biological validity of their findings.

Modern FDR Control Methods: From Traditional Corrections to Advanced Microbiome-Specific Approaches

In the field of microbiome research, differential abundance (DA) testing represents a fundamental statistical task aimed at identifying microbial taxa whose abundance differs significantly between groups of samples, such as healthy versus diseased individuals. A critical challenge in this analysis is the problem of multiple hypothesis testing, where thousands of microbial taxa are tested simultaneously, dramatically increasing the risk of false discoveries. The Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) procedure has emerged as a widely adopted solution to control the false discovery rate (FDR) – the expected proportion of false positives among all significant findings. While the BH procedure provides strong FDR control for independent, continuous test statistics, its performance deteriorates markedly with the sparse, discrete, and zero-inflated data characteristic of microbiome studies. This review systematically evaluates the limitations of the BH procedure in sparse data contexts and benchmarks its performance against emerging methodological alternatives designed specifically for microbiome data analysis.

Theoretical Foundations of the Benjamini-Hochberg Procedure

Core Mechanism and Implementation

The Benjamini-Hochberg procedure is a statistical method designed to control the false discovery rate (FDR) when conducting multiple hypothesis tests. The FDR is defined as the expected proportion of incorrectly rejected null hypotheses (false discoveries) among all rejected hypotheses. The BH procedure operates by adjusting the significance threshold based on the rank of individual p-values [35]. The standard implementation involves four key steps:

- Ordering: Sort all p-values from smallest to largest: ( P{(1)} \leq P{(2)} \leq \ldots \leq P_{(m)} ), where ( m ) represents the total number of hypotheses tested.

- Ranking: Assign ranks to the p-values, with the smallest p-value receiving rank 1, the second smallest rank 2, and so forth.

- Critical Value Calculation: For each ordered p-value ( P_{(i)} ), compute its Benjamini-Hochberg critical value using the formula ( (i/m) \times Q ), where ( i ) is the rank, ( m ) is the total number of tests, and ( Q ) is the chosen false discovery rate threshold.

- Threshold Determination: Identify the largest p-value ( P{(k)} ) that satisfies ( P{(k)} \leq (k/m) \times Q ), and reject all null hypotheses for which ( P \leq P_{(k)} ) [36].

For independent continuous test statistics, the BH procedure guarantees that the FDR does not exceed ( \pi0 \times Q ), where ( \pi0 ) is the proportion of true null hypotheses among all tests [35]. This property makes it particularly suitable for large-scale testing scenarios where more conservative family-wise error rate (FWER) controls would be excessively stringent.

Adaptive BH Procedures and Group Extensions

To improve power, researchers have developed adaptive versions of the BH procedure that first estimate the proportion of true null hypotheses (( \pi0 )) and then apply the FDR control procedure at level ( \alpha / \hat{\pi}0 ). When prior information suggests a natural group structure among hypotheses (e.g., based on Gene Ontology in genomics), the Group Benjamini-Hochberg (GBH) procedure can be employed. This method assigns weights to p-values in each group based on the group-specific proportion of true nulls, thereby increasing power while maintaining FDR control when group proportions differ [35].

Fundamental Limitations of BH in Sparse Microbiome Data

The Discreteness Problem in Test Statistics

Microbiome data presents two characteristics that fundamentally challenge the underlying assumptions of the BH procedure: small sample sizes and extreme data sparsity. In a typical microbiome experiment, sample sizes may range from just ten to a few thousand, while data matrices often contain 80-95% zeros due to both biological absence and technical limitations [37] [38] [2]. These zeros create discrete test statistics whose tail probabilities are smaller than those of continuous test statistics from null distributions. Consequently, the FDR of the BH procedure becomes "overconservative," resulting in much smaller FDR than the nominal level ( \frac{m_0}{m}q ) and substantially reduced power to detect genuinely differentially abundant taxa [37].

Table 1: Factors Contributing to BH Procedure Limitations in Microbiome Data

| Factor | Impact on BH Procedure | Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Small Sample Sizes | Creates discrete test statistics | Overly conservative FDR control |

| Zero Inflation | Reduces effective sample size | Decreased statistical power |

| Compositional Effects | Violates independence assumption | Increased false positive rate |

| High Dimensionality | Extreme multiple testing burden | Reduced power after correction |

Compositionality and Dependence Issues

Microbiome sequencing data is inherently compositional, meaning that the measured abundances represent relative proportions rather than absolute counts. This compositionality creates dependencies among taxa – an increase in one taxon's abundance necessarily causes apparent decreases in others – which violates the independence assumptions underlying the BH procedure [2] [39]. These dependencies can lead to inflated false discovery rates even when applying FDR corrections. Furthermore, the presence of group-wise structured zeros (taxa completely absent in one group but present in another) creates perfect separation problems that standard maximum likelihood-based methods cannot handle effectively, resulting in large parameter estimates with inflated standard errors [38].

Experimental Benchmarking: BH Versus Modern Alternatives

Simulation Frameworks and Performance Metrics

Evaluating the performance of DA methods requires carefully designed simulation studies that incorporate the key characteristics of real microbiome data. Early benchmarking efforts relied on parametric simulations that often failed to capture the true complexity of microbiome data, with machine learning classifiers able to distinguish simulated from real data with near-perfect accuracy [10]. More recent approaches use signal implantation techniques that introduce calibrated abundance and prevalence shifts directly into real taxonomic profiles, thereby preserving the inherent data structure while creating a known ground truth for evaluation.

Table 2: Key Metrics for Evaluating Differential Abundance Methods

| Performance Metric | Definition | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| False Discovery Rate (FDR) | Proportion of false positives among all discoveries | Should be at or below nominal level (e.g., 5%) |

| Sensitivity (Power) | Proportion of true positives correctly identified | Higher values indicate better detection ability |

| False Positive Rate | Proportion of true negatives incorrectly identified | Should be controlled at nominal level |

| Effect Size Correlation | Agreement between estimated and true effect sizes | Important for biological interpretation |

In a comprehensive benchmark evaluating 19 DA methods across multiple realistic simulation scenarios, classic statistical methods (linear models, Wilcoxon test, t-test), limma, and fastANCOM demonstrated the best combination of FDR control and sensitivity. Meanwhile, many methods specifically developed for microbiome data showed unacceptably high false positive rates or insufficient power [10].

Quantitative Performance Comparisons

The discrete FDR (DS-FDR) method, specifically designed to address the limitations of BH in sparse data, demonstrates superior performance in simulation studies. When applied to simulated communities with 100 truly differential taxa, DS-FDR identified approximately 15 more significant taxa than BH and 6 more than filtered BH (FBH) while maintaining FDR below the desired 10% threshold. This advantage was particularly pronounced with small sample sizes (≤20 per group), where DS-FDR detected 24 more taxa than BH and 16 more than FBH on average [37].

A separate large-scale evaluation across 38 real microbiome datasets found dramatic variability in the number of significant features identified by 14 different DA methods. The BH procedure applied after various statistical tests typically identified intermediate numbers of significant ASVs (amplicon sequence variants), while methods like limma-voom and Wilcoxon on CLR-transformed data often identified the largest numbers of significant features [3]. This variability highlights the substantial impact of method choice on biological interpretation.

Figure 1: Workflow for benchmarking differential abundance methods in sparse microbiome data, highlighting the performance divergence between standard BH and specialized alternatives.

Specialized Methods for Sparse Microbiome Data

Methods Addressing Discrete Test Statistics

The discrete FDR (DS-FDR) method represents a direct adaptation to address BH limitations with discrete test statistics. By exploiting the discreteness of the data through a permutation-based approach, DS-FDR achieves higher statistical power to detect significant findings in sparse and noisy microbiome data [37]. This method is relatively robust to the number of non-informative features, potentially removing the need for arbitrary abundance threshold filtering. Empirical demonstrations show that DS-FDR can produce an FDR up to threefold more accurate than standard BH and halve the number of samples required to detect a given effect size [37].

Methods Addressing Compositionality and Zero-Inflation

Another approach combines DESeq2-ZINBWaVE and DESeq2 to address both zero-inflation and group-wise structured zeros. The weighted approach (DESeq2-ZINBWaVE) handles zero-inflation, while DESeq2's penalized likelihood ratio test properly addresses taxa with perfect separation or group-wise structured zeros [38]. Compositionally aware methods like ANCOM-II and ALDEx2 directly model the compositional nature of microbiome data, with benchmarking studies indicating they produce the most consistent results across diverse datasets and agree best with the intersect of results from different approaches [3]. The recently proposed ZicoSeq method draws on the strengths of existing approaches and demonstrates robust FDR control across diverse settings with among the highest power [2].

Table 3: Specialized Differential Abundance Methods for Sparse Microbiome Data

| Method | Core Approach | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DS-FDR | Exploits discreteness via permutations | Increased power for small samples | Requires permutation computation |

| ANCOM-II | Compositional, additive log-ratio | Robust FDR control | Can be conservative |

| ALDEx2 | Compositional, centered log-ratio | Handles compositionality well | Lower power in some settings |

| DESeq2-ZINBWaVE | Weighted zero-inflated model | Addresses both sampling and structural zeros | Complex implementation |

| ZicoSeq | Optimized procedure combining multiple approaches | Robust across diverse settings | Newer, less established |

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Differential Abundance Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| DS-FDR Algorithm | Discrete FDR control for sparse data | Increasing power in small-sample studies |

| ANCOM-II Software | Compositional differential abundance testing | When strict FDR control is prioritized |

| ZINBWaVE Weights | Observation weights for zero-inflated data | Handling extreme zero inflation |

| Signal Implantation Framework | Realistic benchmark data generation | Method evaluation and comparison |

| OPTIMEM Normalization | Compositional effect removal under minimal assumptions | Multi-group and longitudinal studies |

The Benjamini-Hochberg procedure, while foundational for multiple testing correction, demonstrates significant limitations when applied to sparse microbiome data. Its overconservative behavior with discrete test statistics reduces statistical power, potentially obscuring biologically meaningful findings. Experimental benchmarks reveal that no single method universally outperforms others across all dataset types and experimental conditions. However, specialized approaches that explicitly address the discreteness, zero-inflation, and compositionality of microbiome data – including DS-FDR, ANCOM-II, ALDEx2, and ZicoSeq – consistently demonstrate advantages over standard BH in these challenging contexts.

Given the substantial variability in results produced by different DA methods, researchers should adopt a consensus approach based on multiple complementary methods to ensure robust biological interpretations. Future methodological development should focus on creating approaches that simultaneously address all key challenges – discreteness, zero-inflation, compositionality, and dependence – while maintaining computational efficiency and accessibility for practicing researchers. As microbiome studies continue to grow in scale and complexity, particularly with longitudinal and multi-group designs, the development and validation of statistically rigorous DA methods will remain critical for advancing our understanding of microbiome-disease relationships.

Differential abundance (DA) analysis is a cornerstone of microbiome research, aiming to identify microbial taxa whose abundances differ across conditions such as disease states, treatments, or environmental gradients [40]. While numerous statistical methods exist for comparing two groups, many microbiome studies involve multiple groups, sometimes with an inherent order (e.g., disease stages), or require complex study designs with repeated measurements from the same individuals [40] [41]. Analyzing such studies with standard pairwise comparisons is statistically inefficient, leads to high false discovery rates (FDR), and often fails to address the specific scientific question of interest [40].

The ANCOM-BC2 framework was developed specifically to fill this major methodological gap [40] [41]. It extends the capabilities of its predecessor, ANCOM-BC, by providing a formal methodology for multigroup analyses while accounting for sample-specific and taxon-specific biases, handling repeated measures, and adjusting for covariates [40]. This guide provides an objective comparison of ANCOM-BC2's performance against other established methods, focusing on its FDR control and power across various experimental conditions.

Performance Comparison of Differential Abundance Methods

Quantitative Performance Metrics Across Experimental Scenarios

Extensive simulation studies have been conducted to evaluate the performance of DA methods under controlled conditions. The tables below summarize key performance metrics, including False Discovery Rate (FDR) and statistical power, across different experimental scenarios.

Table 1: FDR Control and Power in Continuous Exposure Scenarios (Simulated Data)