Designing Robust Microbiome Studies: A Comprehensive Guide to Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Study Validation

This article provides a comprehensive framework for designing and validating cross-sectional and longitudinal microbiome studies, specifically tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Designing Robust Microbiome Studies: A Comprehensive Guide to Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Study Validation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for designing and validating cross-sectional and longitudinal microbiome studies, specifically tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It addresses the critical methodological challenges in microbiome research, including compositional data analysis, confounder control, and longitudinal instability. The content explores foundational principles, advanced methodological applications like the coda4microbiome toolkit, practical troubleshooting for common pitfalls, and rigorous validation techniques through simulation and benchmarking. By synthesizing current best practices and emerging computational approaches, this guide aims to enhance the reliability, reproducibility, and translational potential of microbiome studies in biomedical and clinical research.

Core Principles and Exploratory Frameworks in Microbiome Study Design

Understanding the Compositional Nature of Microbiome Data and Its Implications

Microbiome data, generated via high-throughput sequencing, is inherently compositional, meaning it conveys relative rather than absolute abundance information. This compositional nature, if ignored, can lead to spurious correlations and false discoveries in both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies [1] [2]. This guide objectively compares analytical methods designed to handle compositionality, evaluating their performance, underlying protocols, and suitability for different research goals. Framed within the validation of cross-sectional and longitudinal study designs, this overview provides researchers and drug development professionals with a framework for selecting robust analytical pipelines that ensure biologically valid and reproducible results.

Microbiome data, derived from techniques like 16S rRNA gene sequencing or metagenomics, is typically presented as a matrix of counts or relative abundances summing to a constant total (e.g., 1 or 100%) per sample [1] [2]. This compositional structure induces dependencies among the observed abundances of different taxa; an increase in the relative abundance of one taxon necessitates an apparent decrease in others [1]. Consequently, standard statistical methods assuming data independence can produce highly misleading results [1] [3].

The challenge is exacerbated in longitudinal studies, where samples collected over time from the same individuals may be affected by distinct batch effects or filtering protocols, effectively representing different sub-compositions at each time point [1]. Furthermore, microbiome data possesses other complex characteristics, including zero-inflation (an excess of zero counts due to true absence or undersampling) and over-dispersion (variance greater than the mean), which must be addressed concurrently with compositionality [2]. Recognizing and properly handling these properties is fundamental to drawing valid inferences about microbial ecology and its role in health and disease.

Methodological Comparison: Core Approaches and Performance

A range of statistical methods has been developed to account for the compositional nature of microbiome data. The table below summarizes the performance and applicability of several key approaches based on recent benchmarking studies [1] [3] [2].

Table 1: Comparison of Methods for Analyzing Compositional Microbiome Data

| Method Category | Examples | Key Principle | Handles Compositionality | Primary Research Goal | Reported Performance and Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log-ratio Transformations | CLR, ILR [2] | Applies logarithms to ratios between components to extract relative information. | Explicitly designed for it. | Differential abundance, Data integration. | Foundational; crucial for valid analysis. Performance can be affected by zero-inflation [3]. |

| Differential Abundance (DA) Testing | ALDEx2 [1], LinDA [1], ANCOM(B C) [1] | Identifies taxa with significantly different abundances between groups. | Varies; many use log-ratios. | Differential abundance. | ALDEx2 and ANCOM are robust but can be conservative. LinDA and fastANCOM offer improved computational efficiency [1]. |

| Predictive Microbial Signatures | coda4microbiome [1], selbal [1] | Identifies a minimal set of microbial features with maximum predictive power for a phenotype. | Yes; based on log-ratio models. | Prediction, Biomarker discovery. | coda4microbiome provides a flexible, interpretable balance between two microbial groups and is applicable to longitudinal data [1]. |

| Global Association Tests | Procrustes, Mantel, MMiRKAT [3] | Tests for an overall association between two omic datasets (e.g., microbiome & metabolome). | Varies; some require pre-transformation. | Global association. | Useful initial step. Power and false-positive rates vary significantly; method choice should be guided by simulation benchmarks [3]. |

| Feature Selection/Integration | sCCA, sPLS [3] | Identifies a subset of relevant, associated features across two high-dimensional datasets. | Often requires pre-transformation (e.g., CLR). | Feature selection, Data integration. | Can identify core associated features but may struggle with high collinearity and complex data structures without careful tuning [3]. |

| Longitudinal-Specific Models | ZIBR [2], NBZIMM [2] | Mixed models that incorporate random effects to account for within-subject correlation over time. | Often applied to transformed or count data. | Longitudinal differential analysis. | Effectively model temporal trajectories and handle zero-inflation and over-dispersion. Computational intensity can be a limitation for very large datasets [2]. |

Beyond the general categories, direct benchmarking of bioinformatic pipelines (e.g., DADA2, MOTHUR, QIIME2) has shown that while different robust pipelines can generate comparable results for major features like Helicobacter pylori abundance and alpha-diversity, their performance can differ in finer details [4]. This underscores the importance of pipeline documentation for reproducibility.

Experimental Protocols and Validation

Core Experimental Workflow for Method Validation

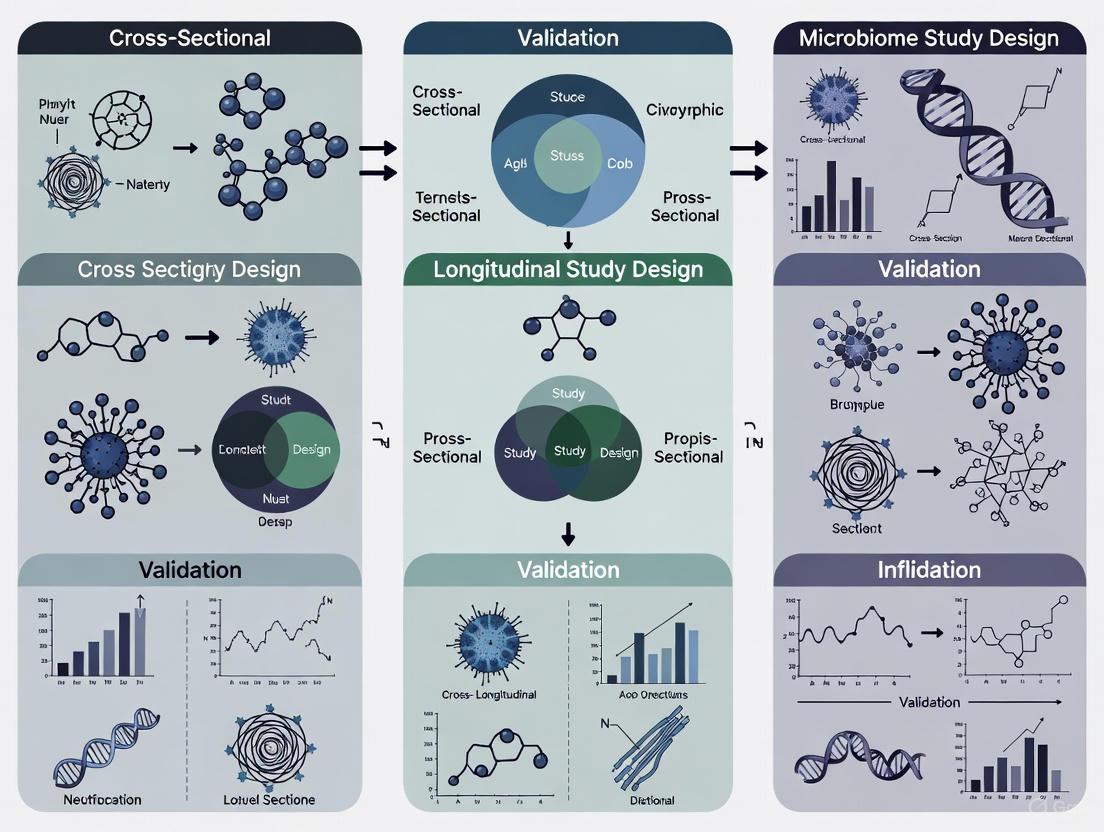

The following diagram outlines a generalized experimental workflow for validating and benchmarking analytical methods for compositional microbiome data, synthesizing approaches from several comparative studies [1] [3] [4].

Detailed Methodologies for Key Experiments

The protocols below detail specific experimental designs used to generate the comparative data cited in this guide.

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Integrative Microbiome-Metabolome Methods [3]

- Aim: To benchmark 19 statistical methods for integrating microbiome and metabolome data across four research goals: global associations, data summarization, individual associations, and feature selection.

- Data Simulation:

- Template Datasets: Three real microbiome-metabolome datasets (Konzo, Adenomas, Autism) were used as templates to estimate realistic marginal distributions (e.g., negative binomial, Poisson, zero-inflated) and correlation structures.

- NORtA Algorithm: The Normal to Anything (NORtA) algorithm was used to generate synthetic microbiome and metabolome data with the same distributional and correlational properties as the templates [3].

- Scenarios: Both null datasets (for Type-I error control) and alternative datasets with varying numbers and strengths of specie-metabolite associations were simulated. Microbiome data was tested under different transformations (CLR, ILR).

- Evaluation: Methods were evaluated on 1000 simulation replicates per scenario based on pre-defined metrics: statistical power, false positive rate, robustness, and interpretability.

Protocol 2: Identification of a Predictive Microbial Signature with coda4microbiome [1]

- Aim: To identify a minimal microbial signature predictive of a phenotype (e.g., disease status) in cross-sectional and longitudinal studies.

- Algorithm Workflow:

- Model Formulation: For cross-sectional data, the algorithm fits a generalized linear model containing all possible pairwise log-ratios (the "all-pairs log-ratio model"):

g(E[Y]) = β₀ + Σ β_jk · log(X_j/X_k). - Variable Selection: Penalized regression (elastic-net) is applied to this model to select the most informative log-ratios while avoiding overfitting [1].

- Signature Interpretation: The final model is reparameterized into a log-contrast model:

M = Σ θ_j · log(X_j), where the sum of the θ_j coefficients is zero. This signature represents a balance between two groups of taxa: those with positive coefficients and those with negative coefficients. - Longitudinal Extension: For longitudinal data, the algorithm calculates the area under the curve (AUC) of pairwise log-ratio trajectories for each sample. Penalized regression is then performed on these AUC summaries to identify a dynamic microbial signature [1].

- Model Formulation: For cross-sectional data, the algorithm fits a generalized linear model containing all possible pairwise log-ratios (the "all-pairs log-ratio model"):

- Validation: Signature performance is assessed via cross-validation to estimate prediction accuracy and avoid overoptimism.

Protocol 3: Comparison of Bioinformatics Pipelines [4]

- Aim: To validate the reproducibility of microbiome composition results across different bioinformatic analysis platforms.

- Design:

- Data: Five independent research groups analyzed the same subset of 16S rRNA gene raw sequencing data (V1-V2 region) from gastric biopsy samples.

- Pipelines: Each group processed the raw FASTQ files using three distinct, commonly used packages: DADA2, MOTHUR, and QIIME2.

- Output Comparison: The resulting microbial diversity metrics (alpha and beta), relative taxonomic abundance, and specific signals (e.g., Helicobacter pylori status) were systematically compared across pipelines and against different taxonomic databases (RDP, Greengenes, SILVA) [4].

- Outcome Measure: Reproducibility was assessed by the consistency of key biological conclusions (e.g., H. pylori positivity) and overall community profiles across the different analytical workflows.

Successful and reproducible microbiome research relies on a suite of computational tools and resources. The following table details key solutions referenced in the featured experiments.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Compositional Microbiome Analysis

| Item Name | Type | Primary Function | Usage in Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| coda4microbiome R Package [1] | Software / Algorithm | Identifies predictive microbial signatures via penalized regression on pairwise log-ratios. | Used for deriving interpretable, phenotype-associated microbial balances from cross-sectional and longitudinal data. |

| ALDEx2 [1] | Software / Algorithm | Differential abundance analysis using a Dirichlet-multinomial model and CLR transformation. | A robust method for identifying taxa with differential relative abundances between study groups. |

| SpiecEasi [3] | Software / Algorithm | Infers microbial interaction networks using sparse inverse covariance estimation. | Used in simulation studies to estimate the underlying correlation networks between microbial species. |

| DADA2, QIIME2, MOTHUR [4] | Bioinformatics Pipeline | Processes raw sequencing reads into amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) or OTUs and assigns taxonomy. | Foundational steps for generating the count tables that are the input for all downstream compositional analysis. |

| SILVA, Greengenes Databases [4] | Reference Database | Curated databases of ribosomal RNA sequences used for taxonomic classification of sequence variants. | Essential for assigning identity to microbial features; choice of database can impact taxonomic assignment. |

| STORMS Checklist [5] | Reporting Guideline | A 17-item checklist for organizing and reporting human microbiome studies. | Ensures complete and transparent reporting of methods, data, and analyses, which is critical for reproducibility and comparative analysis. |

| Mock Communities | Experimental Control | DNA mixes of known microbial composition. | Used as positive controls during sequencing to evaluate the accuracy and bias of the entire wet-lab and bioinformatic pipeline [6]. |

The compositional nature of microbiome data is not a mere statistical nuance but a fundamental property that must be addressed to derive meaningful biological insights. As this comparison illustrates, methods that explicitly incorporate log-ratio transformations or are built upon compositional data analysis principles, such as coda4microbiome, provide a more robust foundation for both cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses compared to standard methods that ignore this structure.

The future of microbiome research, particularly in translational drug development, hinges on methodological rigor and reproducibility. This entails:

- Adopting Compositionally-Aware Methods: Moving beyond correlation analyses of raw relative abundances to methods built for compositional data.

- Utilizing Benchmarking Insights: Leveraging results from systematic comparative studies to select the most powerful and appropriate methods for a given research question [3].

- Embracing Standardized Reporting: Adhering to guidelines like STORMS to ensure that studies are fully documented, transparent, and reproducible [5] [6].

By integrating these practices, researchers can mitigate the risk of spurious findings and accelerate the discovery of robust microbial biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

In the field of microbiome research, the choice of study design is a critical determinant of the validity, reliability, and interpretability of scientific findings. The fundamental objective of microbiome research—to understand the complex, dynamic communities of microorganisms and their interactions with hosts and environments—demands careful consideration of temporal dimensions in study architecture. Cross-sectional and longitudinal approaches represent two distinct methodologies for capturing and analyzing microbial data, each with unique strengths, limitations, and applications. Within the context of microbiome study validation research, selecting the appropriate design is not merely a methodological preference but a foundational element that governs the types of research questions that can be answered, the nature of causal inferences that can be drawn, and the ultimate translation of findings into therapeutic applications. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these two fundamental approaches, offering researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals a framework for making informed design choices in microbiome investigation.

Fundamental Definitions and Key Differences

Core Concepts

Cross-sectional studies are observational research designs that analyze data from a population at a specific point in time [7] [8]. In the context of microbiome research, this approach provides a snapshot of microbial composition and distribution across different groups or populations without following changes over time. Think of it as taking a single photograph of the microbial landscape, capturing whatever fits into the frame at that moment [7]. This design allows researchers to compare many different variables simultaneously, such as comparing gut microbiome profiles between healthy individuals and those with specific diseases, across different age groups, or under varying environmental exposures [7] [9].

Longitudinal studies, by contrast, are observational research designs that involve repeated observations of the same variables (e.g., people, samples) over extended periods—often weeks, months, or even years [10] [11] [12]. In microbiome research, this translates to collecting serial samples from the same subjects to track how microbial communities fluctuate, develop, or respond to interventions over time. Rather than a single photograph, this approach creates a cinematic view of the microbial ecosystem, capturing its dynamic nature and temporal patterns [7] [13].

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Study Designs

| Characteristic | Cross-Sectional Study | Longitudinal Study |

|---|---|---|

| Time Dimension | Single point in time [7] [8] | Multiple time points over an extended period [10] [11] |

| Participants | Different groups (a "cross-section") at one time [8] [11] | Same group of participants followed over time [8] [11] |

| Data Collection | One-time measurement [9] | Repeated measurements [10] |

| Primary Focus | Prevalence, current patterns, and associations [9] [13] | Change, development, and causal sequences [7] [10] |

| Temporal Sequence | Cannot establish [7] [9] | Can establish [7] [10] |

| Cost & Duration | Relatively faster and less expensive [9] [13] | Time-consuming and more expensive [10] [11] |

When to Use Each Design: A Decision Framework

Research Question Alignment

The choice between cross-sectional and longitudinal designs should be primarily driven by the specific research questions under investigation. The following decision pathway provides a systematic approach for selecting the appropriate design based on research objectives:

Application in Microbiome Research

Cross-Sectional Applications

Cross-sectional designs are particularly valuable in microbiome research for:

Disease Association Studies: Identifying microbial signatures associated with specific disease states by comparing microbiome profiles between case and control groups at a single time point [9]. For example, investigating differences in gut microbiota composition between individuals with inflammatory bowel disease and healthy controls.

Population-Level Surveys: Establishing baseline microbiome characteristics across diverse populations, geographic regions, or demographic groups [9]. This approach has been used in large-scale initiatives like the Human Microbiome Project to catalog typical microbial communities in healthy populations.

Hypothesis Generation: Preliminary investigations to identify potential relationships between microbiome features and host factors (diet, lifestyle, genetics) that can be further investigated using longitudinal designs [7] [10].

Protocol Development and Feasibility Testing: Initial method validation and optimization before committing to more resource-intensive longitudinal studies.

Longitudinal Applications

Longitudinal designs are essential in microbiome research for:

Microbial Dynamics: Tracking how microbiome composition and function change over time in response to development, aging, seasonal variations, or environmental exposures [10].

Intervention Studies: Monitoring microbiome responses to therapeutic interventions, including antibiotics, probiotics, dietary changes, or fecal microbiota transplantation [10]. This design allows researchers to establish temporal relationships between interventions and microbial changes.

Disease Progression: Investigating how microbiome alterations precede, accompany, or follow disease onset and progression, potentially identifying predictive microbial biomarkers [10].

Causal Inference: Providing stronger evidence for causal relationships by establishing temporal sequences between microbiome changes and health outcomes, while controlling for time-invariant individual characteristics [7] [10].

Methodological Considerations and Experimental Protocols

Cross-Sectional Study Protocol

Design and Sampling

A well-designed microbiome cross-sectional study requires careful attention to sampling strategies and confounding factors:

Population Definition: Clearly define the target population and establish precise inclusion/exclusion criteria [9]. In microbiome studies, this may include factors such as age, sex, health status, medication use, and dietary habits that significantly influence microbial communities.

Sample Size Calculation: Determine appropriate sample size using power calculations based on expected effect sizes, accounting for multiple comparisons common in microbiome analyses (e.g., alpha-diversity, beta-diversity, differential abundance testing).

Sampling Strategy: Implement stratified or random sampling to ensure representative recruitment [9]. For microbiome studies, consider matching participants based on potential confounders (age, BMI, geography) to minimize their impact.

Standardized Collection Protocols: Establish and rigorously follow standardized protocols for sample collection, processing, storage, and DNA extraction to minimize technical variability.

Data Collection and Analysis

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Microbiome Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function in Microbiome Research | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of microbial genomic DNA from complex samples | Select based on sample type (stool, saliva, skin); critical for representation of diverse taxa |

| 16S rRNA Primers | Amplification of variable regions for bacterial identification | Choice of hypervariable region (V1-V9) influences taxonomic resolution and bias |

| Shotgun Metagenomic Kits | Comprehensive genomic analysis of microbial communities | Enables strain-level resolution and functional profiling; requires higher sequencing depth |

| Storage Stabilizers | Preservation of microbial composition at collection | Prevents shifts in microbial populations between collection and processing |

| Quantitation Standards | Normalization and quality control of DNA samples | Essential for accurate comparison across samples and batches |

Longitudinal Study Protocol

Design and Participant Retention

Longitudinal microbiome studies present unique methodological challenges that require specific strategies:

Wave Frequency and Timing: Determine optimal sampling intervals based on the research question and expected rate of microbiome change. For example, daily sampling may be needed for dietary intervention studies, while monthly or quarterly sampling may suffice for developmental trajectories.

Attrition Mitigation: Implement strategies to minimize participant dropout, which can introduce bias and reduce statistical power [10] [11]. These may include maintaining regular contact, providing incentives, minimizing participant burden, and collecting comprehensive baseline data to characterize potential differences between completers and non-completers.

Case Management Systems: Utilize specialized data collection platforms with unique participant identifiers to maintain data integrity across multiple time points [14] [13]. These systems help prevent duplication, enable seamless follow-up, and centralize data across visits.

Temporal Alignment: Develop protocols for handling irregular intervals between samples and accounting for external factors (seasonality, medications, life events) that may influence microbiome measurements.

Data Management and Statistical Approaches

Longitudinal microbiome data requires specialized analytical techniques:

Data Structure: Organize data to account for within-subject correlations across time points, with unique identifiers linking all samples from the same participant [10] [14].

Statistical Methods: Employ appropriate longitudinal analyses such as:

- Mixed-effects models that account for individual variation while modeling change over time [10]

- Generalized estimating equations (GEE) for modeling population-average effects [10]

- Trajectory analysis to identify patterns of microbiome change across groups

- Time-series analyses for densely sampled data

Missing Data Strategies: Develop pre-specified protocols for handling missing data, which is inevitable in long-term studies [10]. Approaches may include multiple imputation, maximum likelihood estimation, or complete-case analysis with careful interpretation.

Comparative Analysis: Advantages and Limitations

Cross-Sectional Studies

Advantages

Efficiency and Cost-Effectiveness: Can be conducted relatively quickly and inexpensively compared to longitudinal designs [9] [13]. This allows for larger sample sizes and broader hypothesis screening.

Immediate Results: Provide timely data for grant reporting, public health planning, or rapid assessment of microbiome patterns [14] [13].

No Attrition Concerns: Avoid the problem of participant dropout that plagues longitudinal studies [10] [11].

Ethical Considerations: May be the only feasible design for studying certain exposures or conditions where longitudinal follow-up would be impractical or unethical.

Limitations

Temporal Ambiguity: Cannot establish whether exposures preceded outcomes, making causal inference problematic [7] [9]. In microbiome research, this means unable to determine if microbial differences cause disease or result from disease.

Cohort Effects: Findings may reflect generational or historical influences rather than true developmental patterns [12].

Prevalence-Incidence Bias: Capture cases with longer duration, potentially misrepresenting true disease-microbiome relationships [9].

Static Perspective: Provide no information about microbiome stability, resilience, or dynamics in response to perturbations.

Longitudinal Studies

Advantages

Temporal Sequencing: Can establish that microbiome changes precede clinical outcomes, strengthening causal inference [7] [10].

Individual Trajectories: Capture within-person changes, controlling for time-invariant confounders and identifying personalized microbiome patterns [10].

Dynamic Processes: Enable study of microbiome development, succession, stability, and response to interventions [10].

Distinguish Short- and Long-term Effects: Differentiate transient microbial shifts from persistent alterations [12].

Limitations

Resource Intensive: Require substantial time, funding, and organizational infrastructure [10] [11].

Participant Attrition: Loss to follow-up can introduce bias and reduce statistical power [10] [11].

Practice Effects: Repeated testing may influence participant behavior or microbiome through altered awareness or habits [12].

Technical Variability: Changes in laboratory methods or personnel over extended periods may introduce measurement artifacts.

Integration and Hybrid Approaches

Sequential Designs

Many successful microbiome research programs employ sequential designs, beginning with cross-sectional studies to identify promising associations, followed by longitudinal investigations to establish temporal relationships and causal mechanisms [7] [10]. This stepped approach maximizes resource efficiency while building progressively stronger evidence.

Mixed Methods Approaches

For complex research questions, consider integrating both designs:

Nested Longitudinal Studies: Embed intensive longitudinal sampling within a larger cross-sectional cohort to combine population breadth with individual depth.

Accelerated Longitudinal Designs: Study multiple cohorts at different developmental stages simultaneously, combining cross-sectional and longitudinal elements.

Repeated Cross-Sectional Surveys: Conduct independent cross-sectional surveys at regular intervals to monitor population-level microbiome trends over time [9].

In microbiome research, both cross-sectional and longitudinal designs offer distinct and complementary approaches to understanding microbial communities in health and disease. The decision between these designs should be guided by specific research questions, available resources, and the desired strength of evidence. Cross-sectional studies provide efficient snapshots of microbial associations and are ideal for hypothesis generation and prevalence estimation. Longitudinal studies, while more resource-intensive, offer unparalleled insights into microbial dynamics and causal relationships. As microbiome research advances toward interventional studies and clinical applications, the strategic integration of both approaches within well-designed research programs will be essential for validating findings and translating microbial insights into effective therapeutics. By aligning methodological choices with explicit research objectives, scientists can optimize study validity and contribute robust evidence to this rapidly evolving field.

Key Exploratory Questions and Hypothesis Generation for Microbiome Research

Microbiome research has expanded rapidly, producing a large volume of publications across numerous clinical fields. However, despite numerous studies reporting correlations between microbial dysbiosis and host health and disease states, few findings have successfully translated into clinical interventions that impact patient care. For healthcare professionals and drug development researchers, this gap between discovery and clinical application represents a clear call to action, underscoring the critical need for improved translational strategies that effectively bridge basic science and clinical relevance [15]. This challenge is particularly acute in the context of therapeutic development, where the complex, dynamic nature of microbial communities presents unique obstacles not encountered with traditional drug targets.

The field now recognizes that overcoming these translational hurdles requires a fundamental shift in approach. Rather than simply identifying correlative relationships, successful microbiome research must embrace structured, iterative frameworks that move from clinical observation through mechanistic validation and back to clinical application [15]. This complete "translational loop" demands careful consideration of study design, appropriate analytical techniques that account for the compositional nature of microbiome data, and rigorous reporting standards that enable reproducibility and comparative analysis across studies [1] [16]. For pharmaceutical and therapeutic developers, these methodological considerations are not merely academic—they directly impact the viability of microbiome-based diagnostics and interventions in regulated clinical environments.

Foundational Exploratory Questions for Microbiome Study Design

Core Questions Driving Microbiome Research

Table 1: Key Exploratory Questions in Microbiome Research

| Question Category | Specific Research Questions | Study Design Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Microbiome as Outcome | What host, environmental, or therapeutic factors alter microbiome composition and function? | Controlled interventions, longitudinal sampling, multi-omics integration |

| Microbiome as Exposure | How do specific microbial features influence host health, disease risk, or treatment response? | Prospective cohorts, mechanistic models, carefully controlled confounders |

| Microbiome as Mediator | To what extent does the microbiome mediate the effects of other exposures on health outcomes? | Repeated measures, nested case-control, advanced statistical modeling |

| Translational Potential | Can microbial signatures reliably predict disease status or treatment outcomes? | Blind validation cohorts, standardized protocols, defined clinical endpoints |

| Dynamic Properties | How do stability, resilience, and individualized trajectories affect interventions? | High-frequency sampling, long-term follow-up, personalized approaches |

Analytical Considerations for Robust Hypothesis Generation

The compositional nature of microbiome data presents particular challenges for statistical analysis and hypothesis generation. Unlike absolute abundance measurements, microbiome data represent relative proportions constrained by a total sum, creating dependencies among the observed abundances of different taxa [1]. Ignoring this compositional nature can lead to spurious results and false associations, particularly in longitudinal studies where compositions measured at different times may represent different sub-compositions [1]. This has direct implications for drug development, where inaccurate associations could lead to misplaced investment in therapeutic targets.

Emerging approaches address these challenges through compositional data analysis (CoDA) frameworks that extract relative information by comparing parts of the composition through log-ratio transformations [1]. For example, the coda4microbiome algorithm identifies microbial signatures with maximum predictive power using penalized regression on "all-pairs log-ratio models," expressing results as balances between groups of taxa that contribute positively or negatively to a signature [1]. Such methodologies provide more robust foundations for generating hypotheses worthy of further investigation in therapeutic development pipelines.

Methodological Frameworks for Hypothesis Generation

The Iterative Translational Framework

The complex path from initial observation to clinical application benefits from a structured approach. Recent proposals emphasize an iterative framework that cycles between clinical insight and experimental validation [15]. This begins with clinical observations of variability in patient response, symptom clustering, or disease trajectories that don't follow expected patterns. When systematically recorded and paired with biological sampling, these observations become the foundation for hypothesis generation [15].

The growing availability of large, deeply phenotyped cohorts enables exploration of clinical questions at scale. By combining rich clinical metadata with microbiome and metabolome profiling, researchers can build diverse databases or "meta-cohorts" that reveal robust associations between host states and multi-omics profiles [15]. Statistical modeling and machine learning approaches can then identify conserved microbial signatures, host-microbe interactions, or functional pathways associated with specific clinical phenotypes [15] [17], which can then be examined mechanistically to better understand disease etiology and define biomarkers for diagnosis or therapeutic intervention.

Figure 1: The iterative translational framework for microbiome research bridges clinical observations and mechanistic insights through structured cycles of hypothesis generation and experimental validation [15].

From Association to Causation: Experimental Validation Pathways

Once robust associations are identified through clinical observations and large-scale data analysis, the next critical step is determining whether these patterns reflect causal relationships. Experimental models, ranging from in vitro gut culture systems to gnotobiotic animals, allow researchers to examine how specific microbial strains, functions, or metabolites influence host physiology or disease progression [15].

Proof-of-concept studies often begin with fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) from patient subgroups into germ-free or antibiotic-treated mice. If a clinical phenotype, such as altered glucose tolerance, behavior, or treatment responsiveness, is transferred, it suggests that the microbiome may be mechanistically involved in the host state [15]. These findings can then be further dissected using reductionist models, such as monocolonization in germ-free animals, microbiota-organoid systems, or in vitro and ex vivo co-culture assays, to pinpoint the specific microbes, metabolites, and host pathways driving the observed effects [15].

The more closely preclinical models capture human physiology and clinical heterogeneity, the greater their potential to yield findings that are translatable to patient care [15]. This is particularly important for pharmaceutical development, where the limitations of animal models in predicting human responses have been a significant barrier to successful microbiome-based therapeutics.

Comparative Analysis of Microbiome Study Approaches

Cross-Sectional vs. Longitudinal Designs

Table 2: Comparison of Microbiome Study Designs and Analytical Approaches

| Design Aspect | Cross-Sectional Studies | Longitudinal Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Temporal Dimension | Single time point | Multiple time points across hours to years |

| Primary Strengths | Efficient for initial association detection; suitable for large cohorts | Captures dynamics, personalized trajectories, and causal inference |

| Key Limitations | Cannot establish temporal sequence; vulnerable to reverse causation | More costly and logistically complex; requires specialized analysis |

| Analytical Methods | Standard differential abundance testing; diversity comparisons | Time-series analysis; trajectory modeling; rate of change analysis |

| Data Interpretation | Between-subject differences | Within-subject changes and between-subject differences |

| Translational Value | Hypothesis generation; biomarker discovery | Intervention monitoring; personalized medicine applications |

Analytical Techniques for Different Data Types

Different research questions and study designs require specialized analytical approaches. For cross-sectional data, methods like coda4microbiome use penalized regression on all possible pairwise log-ratios to identify microbial signatures with optimal predictive power [1]. The resulting signature is expressed as a balance between two groups of taxa—those that contribute positively and those that contribute negatively to the signature [1].

For longitudinal data, more sophisticated approaches are needed. The coda4microbiome algorithm for longitudinal data infers dynamic microbial signatures by performing penalized regression over summaries of log-ratio trajectories (specifically, the area under these trajectories) [1]. Similarly, novel network inference methods like LUPINE (Longitudinal modeling with Partial least squares regression for Network Inference) leverage conditional independence and low-dimensional data representation to model microbial interactions across time, considering information from all past time points to capture dynamic microbial interactions that evolve over time [18].

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Standards

Standardized Reporting and Methodological Rigor

The interdisciplinary nature of human microbiome research makes consistent reporting of results across epidemiology, biology, bioinformatics, translational medicine, and statistics particularly challenging. Commonly used reporting guidelines for observational or genetic epidemiology studies lack key features specific to microbiome studies [16]. To address this gap, the STORMS (Strengthening The Organization and Reporting of Microbiome Studies) checklist provides a comprehensive framework for reporting microbiome studies [16].

The STORMS checklist is composed of a 17-item checklist organized into six sections that correspond to the typical sections of a scientific publication [16]. This framework emphasizes clear reporting of study design, participant characteristics, sampling procedures, laboratory methods, bioinformatics processing, and statistical analysis—all critical elements for assessing study validity and reproducibility. For drug development professionals, such standardization enables more reliable evaluation of potential microbiome-based biomarkers or therapeutic targets across multiple studies.

Sample Collection and Processing Considerations

Microbiome study results are highly dependent on collection and processing methods, making standardization critical, especially for multi-center trials. The gold standard protocol for stool sampling involves collecting whole stool, homogenizing it immediately, then flash-freezing the homogenate in liquid nitrogen or dry ice/ethanol slurry [19]. However, this approach is often impractical for large studies or real-world clinical settings.

Practical alternatives include Flinders Technology Associate cards, fecal occult blood test cards, and dry swabs of fecal material, which have been shown to be stable at room temperature for days and produce profiles that, while systematically different from flash-frozen samples, retain sufficient accuracy for many applications [19]. The optimal method depends on the specific research question, analytical approach, and practical constraints—factors that must be carefully considered during study design, particularly for clinical trials where consistency across collection sites is essential.

Visualization of Complex Microbiome Dynamics

Network Analysis in Longitudinal Studies

Understanding microbial ecosystems requires more than cataloging which taxa are present—it demands insight into how these taxa interact. Network inference methods reveal these complex interaction patterns, which is particularly valuable in longitudinal studies where these interactions may change over time or in response to interventions [18].

Traditional correlation-based approaches are suboptimal for microbiome data as they ignore compositional structure and can produce spurious results [18]. Partial correlation-based methods, which focus on direct associations by removing indirect associations, provide more valid approaches. The LUPINE method combines one-dimensional approximation and partial correlation to measure linear association between pairs of taxa while accounting for the effects of other taxa, making it suitable for scenarios with small sample sizes and small numbers of time points [18].

Figure 2: Dynamic microbial network transitions between time points, illustrating how microbial interactions can change over time or in response to interventions, as captured by longitudinal network inference methods like LUPINE [18].

Research Reagent Solutions and Methodological Toolkit

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Microbiome Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Methods | Primary Applications | Considerations for Selection |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | Commercial kits with bead-beating | Microbial community DNA isolation | Efficiency for Gram-positive bacteria; inhibitor removal |

| 16S rRNA Primers | V1-V9 region-specific primers | Taxonomic profiling | Target region selection affects resolution and bias |

| Storage/Preservation | RNAlater, FTA cards, freezing | Sample preservation | Compatibility with downstream analyses; practicality |

| Computational Tools | coda4microbiome, LUPINE, QIIME2 | Data analysis | Compositional data awareness; longitudinal capabilities |

| Reference Databases | Greengenes, SILVA, GTDB | Taxonomic classification | Currency; curation quality; phylogenetic consistency |

| Experimental Models | Gnotobiotic mice, organoids, in vitro systems | Mechanistic validation | Human relevance; throughput; physiological accuracy |

Successful microbiome research requires navigating the complex interplay between study design, analytical methodology, and biological validation. The field has moved beyond simple correlation studies toward more sophisticated approaches that account for the compositional nature of microbiome data, dynamic changes over time, and the need for mechanistic validation [15] [1] [18]. For researchers and drug development professionals, this evolution offers both challenges and opportunities.

The most promising path forward involves iterative approaches that cycle between clinical observation and experimental validation, using appropriate analytical techniques for the specific research question and study design [15]. By adopting standardized reporting frameworks [16], validating findings in physiologically relevant models [15], and employing compositional data-aware statistical methods [1], microbiome research can better overcome the bench-to-bedside divide and deliver on its promise for innovative diagnostics and therapeutics.

Sample Acquisition and Storage: The Foundation of Reliable Data

The integrity of any microbiome study is determined at the very first step: sample acquisition. Inappropriate collection or storage can introduce significant bias, making subsequent analytical results unreliable.

Sampling Methodologies by Body Site

Table 1: Comparison of Sampling Methods for Different Body Sites

| Body Site | Sampling Method | Protocol Details | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feces (Gut) | Pre-moistened Wipe | Patient wipes after defecation, folds wipe, and places in a biohazard bag for transport. Frozen at -20°C upon receipt [20]. | Non-invasive, suitable for home collection. | Does not capture mucosa-associated or small intestine microbes [21]. |

| Stool Method (for viable microbes) | Patient collects stool in a "toilet hat." Sample is placed in a cup and mixed with a preservative solution like modified Cary-Blair medium [20]. | Preserves viability of anaerobic microbes. | More complex for patients; involves handling stool directly. | |

| Oral | Saliva | Patient spits into a 50 ml conical tube until 5 ml of liquid saliva is collected [20]. | Simple and non-invasive. | Can take 2-5 minutes to produce sample [20]. |

| Buccal Swab | A soft cotton tip swab is used to rub the inside of the cheek [20]. | Targets microbes adherent to epithelial cells. | Captures a different niche than saliva. | |

| Vaginal/Skin | Flocked Swab | A physician collects sample during a clinic visit using a flocked nylon swab [20]. | Standardized collection by professional. | Invasive; requires a clinic visit. |

Sample Storage and Stabilization

Storage conditions profoundly impact microbial community profiles. While immediate freezing at -80°C is the gold standard, it is often impractical for at-home collection [22] [19].

Table 2: Comparison of Sample Storage Methods

| Storage Method | Protocol | Impact on Microbiome Profile (after 72 hours) | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| -80°C Freezing | Immediate flash-freezing of homogenized sample [19]. | Gold standard reference profile. | Laboratory settings where immediate processing is possible. |

| +4°C Refrigeration | Storage in a standard refrigerator [22]. | No significant alteration in diversity or composition compared to -80°C [22]. | Short-term storage and transport when freezing is not immediately available. |

| Room Temperature (Dry) | Storage at ambient temperature without additives [22]. | Significant divergence from -80°C profile; lower diversity and evenness [22]. | Not recommended unless necessary; maximum 24 hours may be acceptable [21]. |

| OMNIgene.GUT Kit | Commercially available kit for ambient temperature storage [22]. | Minimal alteration; performs better than other room-temperature methods [22]. | Large-scale studies and mail-in samples where cold chain is impossible. |

| RNAlater | Sample immersion in RNA preservative solution [22]. | Significant divergence in phylum-level abundance and evenness [22]. | When simultaneous RNA analysis is intended; mixed success for microbiome profiling [19]. |

| 95% Ethanol | Sample immersion in 95% ethanol [21]. | Effective for preserving composition for DNA analysis [21]. | Low-cost stabilization method; may preclude some transport modes. |

| FTA Cards | Smearing sample on filter paper cards [21] [19]. | Stable at room temperature for days; induces small systematic shifts [19]. | Extremely practical for mail-in surveys and amplicon sequencing. |

Wet-Lab Processing: From Sample to Sequence

Once samples are collected and stabilized, the wet-lab phase begins to extract and prepare genetic material for sequencing.

DNA Extraction and Library Preparation

Robust DNA extraction is critical. The use of cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) is a documented method for effective lysis of microbial cells in fecal samples [23]. The choice between 16S rRNA gene sequencing and shotgun metagenomics depends on the research question and budget.

- 16S rRNA Gene Amplicon Sequencing: This method uses polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to amplify hypervariable regions (e.g., V4) of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene. A typical protocol uses primers 5′-CCTAYGGGRBGCASCAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GACTACNNGGGTATCTAAT-3′ (reverse) followed by sequencing on an Illumina NovaSeq platform [23]. It is cost-effective for profiling bacterial composition but offers limited functional and taxonomic resolution.

- Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing: This technique sequences all the DNA in a sample, allowing for species- or strain-level identification and functional profiling of the entire microbial community, including viruses and eukaryotes [24] [25]. Processing is more complex and often requires pipelines like bioBakery [26].

Research Reagent Solutions for Wet-Lab Processing

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Kits for Microbiome Analysis

| Reagent/Kits | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| CTAB Lysis Buffer | Disrupts cell membranes to release genomic DNA. | Primary DNA extraction from complex samples like stool [23]. |

| High-Fidelity PCR Master Mix | Amplifies DNA with high accuracy for sequencing. | 16S rRNA gene amplification prior to library prep [23]. |

| TruSeq DNA PCR-Free Kit | Prepares sequencing libraries without amplification bias. | Construction of shotgun metagenomic libraries for Illumina sequencing [23]. |

| OMNIgene.GUT Kit | Stabilizes microbial DNA at ambient temperature. | Population studies involving mail-in samples [22]. |

| RNAlater | Preserves RNA and DNA in tissues and cells. | Stabilization for metatranscriptomic studies; mixed results for microbiome DNA [24] [22]. |

Bioinformatic Analysis: Unlocking the Data

The raw sequencing data must be processed through a bioinformatic pipeline to generate biologically meaningful information.

Sequence Preprocessing and Quality Control

The first computational step ensures data quality. For 16S data, this involves quality filtering, chimera removal, and clustering sequences into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) or denoising into Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) at 97% similarity [24] [23]. Standard tools include FastP for quality control and Uparse for OTU clustering [23]. For shotgun data, host DNA must be filtered out before analysis [25].

Data Transformation and Normalization

Microbiome sequencing data is compositional, sparse, and over-dispersed, making normalization and transformation essential before statistical analysis or machine learning [24] [26].

Table 4: Common Data Transformation and Normalization Methods

| Method | Description | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rarefaction | Subsampling sequences to the same depth per sample. | Simple; makes samples comparable. | Discards data; can reduce statistical power [24]. |

| Total Sum Scaling (TSS) | Converts counts to relative abundances. | Intuitive and widely used. | Does not address compositionality; sensitive to outliers. |

| Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) | A compositional transformation using log-ratios. | Handles compositionality; suitable for many models [26]. | Requires imputation of zeros, which can be tricky. |

| CSS (Cumulative Sum Scaling) | Normalizes using a cumulative sum of counts up to a data-derived percentile. | Robust to outliers; performs well in comparative studies [24]. | Implemented in specific pipelines like metagenomeSeq. |

Statistical and Machine Learning Analysis

The analytical phase tests specific hypotheses and builds predictive models.

- Alpha and Beta Diversity: Alpha diversity (within-sample diversity) is measured with indices like Shannon and Chao1. Beta diversity (between-sample diversity) is visualized using PCoA plots and measured with metrics like Bray-Curtis dissimilarity [23]. PERMANOVA is used to test for significant group differences in community structure [22].

- Differential Abundance: Identifying taxa that differ between groups (e.g., patients vs. controls) is a core task. Methods like LEfSe (Linear Discriminant Analysis Effect Size) and ANCOM-BC are designed to handle compositional data [23].

- Machine Learning: Random Forest is a popular algorithm for building diagnostic models from microbiome data [26] [23]. The process involves splitting data into training and test sets (e.g., 80/20), performing cross-validation, and ranking feature importance to identify key microbial biomarkers [23]. For example, a three-species model for acute pancreatitis achieved an AUC of 0.94 [23].

Reporting and Standardization: Ensuring Reproducibility

The field has moved towards standardized reporting to enhance reproducibility and comparability across studies. The STORMS (Strengthening The Organization and Reporting of Microbiome Studies) checklist provides a 17-item framework covering all aspects of a manuscript, from abstract to discussion [16]. Key reporting items include:

- Study Design: Clearly stating if the study is cross-sectional, case-control, or cohort [16].

- Participant Details: Reporting inclusion/exclusion criteria, and information on antibiotic use [16].

- Laboratory and Bioinformatics: Detailing DNA extraction, sequencing protocols, and bioinformatic tools with version numbers [16].

- Data Availability: Making raw sequencing data publicly available in repositories like the Sequence Read Archive (SRA).

Advanced Methodologies and Practical Applications for Study Implementation

Microbiome data, generated by high-throughput sequencing technologies, are inherently compositional [27]. This means that the data represent relative abundances of different taxa, where the total number of sequences per sample is fixed by the sequencing instrument rather than reflecting absolute cell counts [27]. Each sample's microbial abundances are constrained to sum to a constant (typically 1 or 100%), forming what is known as a "whole" or "total" [28]. This constant-sum constraint means that the abundance of one taxon is not independent of others; an increase in one necessarily leads to decreases in others [27] [29]. Consequently, standard statistical methods assuming Euclidean geometry often produce spurious correlations and misleading results when applied directly to raw compositional data [30] [27].

The field of Compositional Data Analysis (CoDA), founded on John Aitchison's pioneering work, provides a rigorous statistical framework for analyzing such data by treating them as residing on a simplex rather than in traditional Euclidean space [30]. The core principle of CoDA is to extract relative information through log-ratio transformations of the component parts, which "open" the simplex into a real vector space where standard statistical and machine learning techniques can be validly applied [30] [31]. This approach ensures two fundamental principles: scale invariance (where only relative proportions matter) and sub-compositional coherence (where inferences from a subset of parts agree with those from the full composition) [30].

Fundamental Log-Ratio Transformations in CoDA

Core Transformation Types

Several log-ratio transformations form the foundation of CoDA, each with distinct characteristics and use cases.

Table 1: Core Log-Ratio Transformations in Compositional Data Analysis

| Transformation | Acronym | Definition | Key Characteristics | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centered Log-Ratio | CLR | ( \text{clr}(xj) = \log\frac{xj}{(\prod{k=1}^D xk)^{1/D}} ) | Centers components around geometric mean; Creates a covariance matrix that is singular [30] [29]. | Exploratory analysis; PCA on compositional data; When symmetric treatment of components is desired. |

| Additive Log-Ratio | ALR | ( \text{alr}(xj) = \log\frac{xj}{xD} ) (where ( xD ) is reference component) | Uses a fixed reference component; Results in non-orthogonal coordinates [30] [29]. | When a natural baseline component exists; Easier interpretation than ILR. |

| Isometric Log-Ratio | ILR | ( \text{ilr}(x) = \Psi^T \log(x) ) (where ( \Psi ) is an orthonormal basis) | Creates orthonormal coordinates in Euclidean space; Statistically elegant but difficult to interpret [30]. | When orthogonality is required; Advanced statistical modeling. |

| Pairwise Log-Ratio | PLR | ( \text{plr}{jk} = \log\frac{xj}{x_k} ) for all ( j < k ) | Creates all possible pairwise ratios between components; Can lead to combinatorial explosion in high dimensions [30] [1]. | Feature selection; Identifying important relative relationships between specific components. |

Addressing the Zero Problem

A significant challenge in applying log-ratio transformations to microbiome data is the presence of zeros (unobserved taxa) in the dataset [29] [32]. Since the logarithm of zero is undefined, these values must be addressed before transformation. Multiple strategies exist for handling zeros:

- Replacement strategies: Zeros can be replaced with a small positive value, such as using Bayesian-multiplicative replacement or other imputation methods [32].

- Novel transformations: The chiPower transformation has been proposed as an alternative that naturally accommodates zeros while approximating the properties of log-ratio transformations [32]. This approach combines chi-square standardization with a Box-Cox power transformation and can be tuned to optimize analytical outcomes.

- Model-based approaches: Some analysis pipelines incorporate zero-handling directly into their modeling framework, using techniques like penalized regression that can handle sparse data [1] [31].

Comparative Performance of Log-Ratio Methods

Experimental Evidence from Benchmarking Studies

Several studies have systematically compared the performance of different log-ratio transformations in microbiome data analysis. A comprehensive experiment using the Iris dataset (artificially closed to mimic compositional data) compared the performance of a Random Forest classifier across different transformation approaches [30].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Log-Ratio Transformations on Iris Dataset Classification

| Transformation Method | Mean Accuracy (%) | Performance Variability | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raw Features | Baseline | High | None (serves as baseline) |

| CLR | Solid Improvement | Moderate | Symmetric treatment of components |

| ALR | High Improvement | Low | Interpretability with natural baseline |

| PLR | Highest (96.7%) | Lowest | Captures rich pairwise relationships |

| ILR | Solid Improvement | Moderate | Orthogonal coordinates |

The results demonstrated that all log-ratio transformations outperformed raw features, with PLR achieving the highest mean accuracy (96.7%) and lowest variability across cross-validation folds [30]. This performance advantage highlights how log-ratios unlock predictive relationships that raw compositional features obscure.

coda4microbiome: A Specialized Tool for Microbial Signature Identification

The coda4microbiome R package implements a sophisticated CoDA approach specifically designed for microbiome studies [1] [31]. Its algorithm relies on penalized regression on the "all-pairs log-ratio model" - a generalized linear model containing all possible pairwise log-ratios:

[ g(E(Y)) = \beta0 + \sum{1 \le j < k \le K} \beta{jk} \cdot \log(Xj/X_k) ]

where the regression coefficients are estimated by minimizing a loss function ( L(\beta) ) subject to an elastic-net penalization term [1] [31]:

[ \hat{\beta} = \text{argmin}{\beta} \left{ L(\beta) + \lambda1 ||\beta||2^2 + \lambda2 ||\beta||_1 \right} ]

This approach identifies microbial signatures expressed as balances between two groups of taxa: those contributing positively to the signature and those contributing negatively [1] [31]. For longitudinal studies, coda4microbiome infers dynamic microbial signatures by performing penalized regression on summaries of log-ratio trajectories (the area under these trajectories) across time points [31].

Experimental Protocols for CoDA Implementation

Standard CoDA Workflow for Microbiome Data

Figure 1: Standard Compositional Data Analysis Workflow for Microbiome Studies

Specialized Protocol for Longitudinal Microbiome Analysis

For longitudinal microbiome studies, additional considerations are necessary to account for temporal dynamics [31]:

Data Structure Preparation: Organize data to include subject identifiers, time points, and phenotypic variables alongside taxonomic abundances.

Trajectory Calculation: For each subject and pairwise log-ratio, compute the trajectory across all available time points.

Trajectory Summarization: Calculate summary measures of log-ratio trajectories, typically the area under the curve (AUC).

Penalized Regression: Apply elastic-net penalized regression to the summarized trajectory data to identify microbial signatures:

[ \hat{\beta} = \text{argmin}{\beta} \left{ \sum{i=1}^n (Yi - Mi\beta)^2 + \lambda \left( \frac{1-\alpha}{2} ||\beta||2^2 + \alpha ||\beta||1 \right) \right} ]

where ( Mi = \sum{1 \le j < k \le K} \beta{jk} \cdot \log(X{ij}/X_{ik}) ) represents the microbial signature score for subject ( i ) [31].

- Signature Interpretation: Express the resulting signature as a balance between groups of taxa and validate using cross-validation approaches.

Advanced Methodologies and Emerging Alternatives

Network Inference with LUPINE

For inferring microbial networks from longitudinal data, the LUPINE (LongitUdinal modelling with Partial least squares regression for NEtwork inference) methodology offers a novel approach [18]. LUPINE uses partial correlation to measure associations between taxa while accounting for the effects of other taxa, with dimension reduction through principal components analysis (for single time points) or PLS regression (for multiple time points) [18]. The method is particularly suited for scenarios with small sample sizes and few time points, common challenges in longitudinal microbiome studies [18].

chiPower Transformation as a Log-Ratio Alternative

The chiPower transformation presents an alternative to traditional log-ratio methods, particularly beneficial for datasets with many zeros [32]. This approach combines the standardization inherent in chi-square distance with Box-Cox power transformation elements [32]. The transformation is defined as:

[ \text{chiPower}(x) = \frac{x^\gamma - 1}{\gamma \cdot m^{\gamma-1}} ]

where ( \gamma ) is the power parameter and ( m ) is the geometric mean of the component [32]. The power parameter can be tuned to approximate logratio distances for strictly positive data or optimized for prediction accuracy in supervised learning contexts [32].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Key Software Tools for Compositional Microbiome Analysis

| Tool/Package | Primary Function | Key Features | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| coda4microbiome (R package) | Microbial signature identification | Penalized regression on all pairwise log-ratios; Cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis [1] [31]. | Case-control studies; Disease biomarker discovery; Temporal microbiome dynamics. |

| ALDEx2 (R package) | Differential abundance analysis | Uses CLR transformation; Accounts for compositional nature; Robust to sampling variation [33]. | Differential abundance testing between conditions; Group comparisons. |

| LUPINE (R code) | Longitudinal network inference | Partial correlation with dimension reduction; Handles multiple time points sequentially [18]. | Microbial network analysis; Temporal interaction studies. |

| SelEnergyPerm | Sparse PLR selection | Identifies sparse set of discriminative pairwise log-ratios; Combines with permutation testing [30]. | High-dimensional biomarker discovery; Feature selection. |

| DiCoVarML | Targeted PLR with constrained regression | Uses nested cross-validation; Optimized for prediction accuracy [30]. | Predictive modeling; Machine learning with compositional features. |

Implementation of appropriate log-ratio transformations is crucial for valid analysis of microbiome data, preventing spurious correlations and misleading conclusions that arise from ignoring compositional nature [27]. The evidence consistently demonstrates that CoDA methods outperform naive approaches that treat relative abundances as absolute measurements [30].

For cross-sectional studies, CLR and PLR transformations generally provide the strongest performance, with PLR particularly effective for predictive modeling [30]. For longitudinal studies, coda4microbiome offers a specialized framework for identifying dynamic microbial signatures [31]. Emerging methods like LUPINE for network inference [18] and chiPower transformation for zero-heavy datasets [32] continue to expand the CoDA toolkit.

When implementing CoDA, researchers should carefully consider their specific research question, data characteristics (particularly zero inflation), and analytical goals to select the most appropriate transformation and analytical pipeline.

Microbiome data generated from high-throughput sequencing is inherently compositional, meaning that the data represent relative proportions rather than absolute abundances. This compositionality imposes a constant-sum constraint, creating dependencies among the observed abundances of different taxa. Analyses that ignore this fundamental property can produce spurious results and misleading biological conclusions [31] [34]. The coda4microbiome R package addresses this challenge by implementing specialized Compositional Data Analysis (CoDA) methods specifically designed for microbiome studies across various research designs [31] [35].

The toolkit's primary aim is predictive modeling—identifying microbial signatures with maximum predictive power using the minimum number of features [31]. Unlike differential abundance testing methods that focus on characterizing microbial communities by selecting taxa with significantly different abundances between groups, coda4microbiome is designed for prediction accuracy, making it particularly valuable for developing diagnostic or prognostic biomarkers [31]. The package has evolved from earlier algorithms like selbal, offering a more flexible model and computationally efficient global variable selection method that significantly reduces computation time [31].

Methodological Framework and Core Algorithms

Fundamental Principles of the coda4microbiome Approach

The coda4microbiome methodology is built upon three core principles that ensure proper handling of compositional data while maintaining biological interpretability. First, the algorithm employs log-ratio analysis, which extracts relative information from compositional data by comparing parts of the composition rather than analyzing individual components in isolation [31] [36]. Second, it implements penalized regression for variable selection, effectively handling the high dimensionality of microbiome data where the number of taxa typically exceeds the number of samples [31]. Third, the method produces interpretable microbial signatures expressed as balances between two groups of taxa—those contributing positively to the signature and those contributing negatively [31] [34].

This approach ensures the invariance principle required for compositional data analysis, meaning results are independent of the scale of the data and remain consistent whether using relative abundances or raw counts [31]. The algorithm automatically handles zero values in the data through simple imputation, though users can apply more advanced zero-imputation methods from specialized packages like zCompositions as a preprocessing step [37].

Core Algorithm for Cross-Sectional Studies

For cross-sectional studies, coda4microbiome utilizes the coda_glmnet() function, which implements a penalized generalized linear model on all possible pairwise log-ratios [31] [37]. The model begins with the "all-pairs log-ratio model" expressed as:

$$g(E(Y)) = \beta0 + \sum{1≤j

where $Y$ represents the outcome variable, $Xj$ and $Xk$ are the abundances of taxa $j$ and $k$, and $g()$ is the link function appropriate for the outcome type (e.g., logit for binary outcomes, identity for continuous outcomes) [31].

The regression coefficients are estimated by minimizing a loss function subject to an elastic-net penalization term:

$$\hat{\beta} = \text{argmin}{\beta} \left{L(\beta) + \lambda1 \|\beta\|2^2 + \lambda2 \|\beta\|_1\right}$$

This penalized regression is implemented through cross-validation using the cv.glmnet() function from the glmnet R package, with the default α parameter set to 0.9 (providing a mix of L1 and L2 regularization) and the optimal λ value selected through cross-validation [31] [37]. The result is a sparse model containing only the most relevant pairwise log-ratios for prediction.

Table 1: Key Functions in coda4microbiome for Different Study Designs

| Study Design | Core Function | Statistical Model | Key Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-sectional | coda_glmnet() |

Penalized GLM on all pairwise log-ratios | Microbial signature as balance between two taxon groups |

| Longitudinal | coda_glmnet_longitudinal() |

Penalized regression on AUC of log-ratio trajectories | Dynamic signature showing different temporal patterns |

| Survival | coda_cox() |

Penalized Cox regression on all pairwise log-ratios | Microbial risk score associated with event risk |

Algorithm for Longitudinal Studies

For longitudinal studies, coda4microbiome employs the coda_glmnet_longitudinal() function, which adapts the core algorithm to handle temporal data [31]. Instead of analyzing single time points, the algorithm calculates pairwise log-ratios across all time measurements for each subject, creating a trajectory for each log-ratio. The method then computes the area under the curve (AUC) for these trajectories, summarizing the overall temporal pattern of each log-ratio [31].

These AUC values then serve as inputs to a penalized regression model, following a similar approach to the cross-sectional method. This innovative approach allows identification of dynamic microbial signatures—groups of taxa whose relative abundance patterns over time differ between study groups (e.g., cases vs. controls) [31]. The interpretation of longitudinal results focuses on these temporal dynamics, providing insights into how microbial community dynamics relate to health outcomes.

Extension to Survival Studies

The recently developed extension for survival studies implements coda_cox(), which performs penalized Cox proportional hazards regression on all possible pairwise log-ratios [36] [38]. The model specifies the hazard function as:

$$h(t|X) = h0(t) \exp\left(\sum{1≤j

Variable selection is achieved through elastic-net penalization of the log partial likelihood, with the optimal penalization parameter selected by maximizing Harrell's C-index through cross-validation [36]. The resulting microbial signature provides a microbial risk score that quantifies the association between the microbiome composition and the risk of experiencing the event of interest.

Diagram 1: Core Computational Workflow of coda4microbiome. The algorithm processes microbiome data through log-ratio transformation, penalized regression, and reparameterization to produce interpretable microbial signatures applicable to multiple study designs.

Performance Benchmarking and Experimental Validation

Simulation Studies and Comparison with Alternative Methods

Simulation studies comparing coda4microbiome with other microbiome analysis methods demonstrate its competitive performance in predictive accuracy [31]. The algorithm has been benchmarked against both general machine learning approaches and specialized compositional methods across various data structures and signal strengths.

In simulations with a binary outcome, coda4microbiome achieved high predictive accuracy while maintaining interpretability—a key advantage over "black box" machine learning approaches [31]. The method's signature, expressed as a balance between two groups of taxa, provides immediate biological interpretation that is often missing from other high-dimensional approaches. When compared to other compositional methods like ALDEx2, LinDA, ANCOM, and fastANCOM—which primarily focus on differential abundance testing rather than prediction—coda4microbiome showed superior performance for predictive modeling tasks [31].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Microbiome Analysis Methods

| Method | Primary Purpose | CoDA-Compliant | Interpretability | Longitudinal Support | Key Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| coda4microbiome | Prediction | Yes | High (taxon balances) | Yes | Optimized for predictive signatures |

| ALDEx2 | Differential abundance | Yes | Medium | No | Difference detection between groups |

| LinDA | Differential abundance | Yes | Medium | Limited | Linear model framework |

| ANCOM/ANCOM-BC | Differential abundance | Yes | Medium | No | Handles compositionality effectively |

| Selbal | Balance identification | Yes | High | No | Predecessor with similar philosophy |

| Standard ML | Prediction | No | Low | With adaptation | Flexible prediction algorithms |

Application to Real Datasets: Crohn's Disease Case Study

The coda4microbiome methodology was validated on a real Crohn's disease dataset comprising 975 individuals (662 patients with Crohn's disease and 313 controls) with microbiome compositions measured at 48 genera [37]. Application of coda_glmnet() to this dataset identified a microbial signature consisting of 24 genera that effectively discriminated between Crohn's disease cases and controls.

The signature demonstrated high classification accuracy with an apparent AUC of 0.85 and a cross-validation AUC of 0.82 (SD = 0.008), indicating strong predictive performance [37]. A permutation test (100 iterations) confirmed the significance of these results, with null distribution AUC values ranging between 0.47-0.55, far below the observed performance [37].

The Crohn's disease signature was expressed as a balance between two groups of taxa. The group positively associated with Crohn's disease included 11 genera such as g__Roseburia, f__Peptostreptococcaceae_g__, and g__Bacteroides, while the negatively associated group included 13 genera such as g__Adlercreutzia, g__Eggerthella, and g__Aggregatibacter [37]. This balance provides immediate biological interpretation for hypothesis generation and validation.

Longitudinal Analysis: Early Childhood Microbiome Study

In the Early Childhood and the Microbiome (ECAM) study, coda4microbiome successfully identified dynamic microbial signatures associated with infant development [31]. The longitudinal analysis revealed taxa whose relative abundance trajectories differed significantly based on feeding mode (breastfed vs. formula-fed) and other developmental factors.

The algorithm identified two groups of taxa with distinct temporal patterns: one group showing increasing relative abundance over time in breastfed infants, and another group showing the opposite pattern. These dynamic signatures provide insights into how microbial succession patterns in early life relate to environmental exposures and potentially to later health outcomes [31].

Practical Implementation and Research Applications

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing coda4microbiome in research requires several key computational tools and resources. The core package is available from CRAN (the Comprehensive R Archive Network) and can be installed directly within R using the command install.packages("coda4microbiome") [31] [35]. The project website (https://malucalle.github.io/coda4microbiome/) provides comprehensive tutorials, vignettes with detailed function descriptions, and example analyses for different study designs [31] [34].

For data preprocessing, several complementary R packages are recommended. The zCompositions package offers advanced methods for zero imputation in compositional data, which can be used prior to applying coda4microbiome functions [37]. The glmnet package is required for the penalized regression implementation [31] [37], while ggplot2 and other visualization packages enhance the graphical capabilities for creating publication-quality figures of the results.

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for coda4microbiome Implementation

| Tool/Package | Purpose | Key Features | Implementation in coda4microbiome |

|---|---|---|---|

| coda4microbiome R package | Core analysis | Microbial signature identification | Primary analytical framework |

| glmnet | Penalized regression | Elastic-net implementation | Backend for variable selection |

| zCompositions | Zero imputation | Censored data methods | Optional preprocessing step |

| ggplot2 | Visualization | Customizable graphics | Enhanced plotting capabilities |

| CRAN repository | Package distribution | Standard R package source | Primary installation source |

Experimental Protocol for Cross-Sectional Studies

Implementing coda4microbiome for cross-sectional studies follows a standardized protocol. First, researchers should load the required packages and import their data, ensuring that the microbiome data is formatted as a matrix (samples × taxa) and the outcome as an appropriate vector (binary, continuous, or survival time) [37]. The basic function call for a binary outcome is:

The algorithm automatically detects the outcome type (binary, continuous, or survival) and implements the appropriate model [37]. For binary outcomes, it performs penalized logistic regression; for continuous outcomes, linear regression; and for survival data, Cox proportional hazards regression [37]. The default penalization parameter (lambda = "lambda.1se") provides the most regularized model within one standard error of the minimum, but users can specify lambda = "lambda.min" for the model with minimum cross-validation error [37].