From Bench to Bedside: The Clinical Translation of the Human Microbiome in Diagnostics and Therapeutics

This article synthesizes the rapid evolution of microbiome science from a research field to a cornerstone of clinical innovation.

From Bench to Bedside: The Clinical Translation of the Human Microbiome in Diagnostics and Therapeutics

Abstract

This article synthesizes the rapid evolution of microbiome science from a research field to a cornerstone of clinical innovation. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational mechanisms by which the microbiome influences health and disease, the burgeoning pipeline of microbiome-based diagnostics and live biotherapeutic products (LBPs), and the critical methodological and regulatory challenges that remain. By examining current applications—from FDA-approved therapies for recurrent C. difficile infection to microbiome-based stratification for cancer immunotherapy—and outlining a roadmap for standardization and validation, this review provides a comprehensive overview of the opportunities and hurdles in integrating microbiome science into precision medicine.

The Microbiome Paradigm: From Passive Bystander to Active Therapeutic Target

The human microbiome has undergone a profound conceptual shift, from being considered a passive bystander to being recognized as a dynamic and essential determinant of human physiology [1]. This complex ecosystem of microorganisms actively shapes immunity, metabolism, neurodevelopment, and therapeutic responsiveness across the lifespan through intricate crosstalk with host pathways [1]. Advances in multi-omic technologies and computational approaches have revealed mechanistic insights into how microbial communities modulate host systems across diverse body sites, accelerating the clinical translation of this knowledge for diagnostic and therapeutic applications [1] [2] [3]. This document outlines the core principles, key applications, and detailed methodological protocols for investigating the microbiome's role in human physiology and disease, providing researchers with practical tools for advancing microbiome science toward clinical implementation.

Diagnostic Potential of Microbiome-Associated Metabolites

The microbiome exerts profound influence on host physiology through the production and modulation of metabolites that enter systemic circulation. These microbiome-associated metabolites serve as quantifiable biomarkers for disease risk and progression, offering significant diagnostic potential [2].

Table 1: Key Microbiome-Associated Metabolite Classes and Their Diagnostic Relevance

| Metabolite Class | Representative Metabolites | Physiological Association | Diagnostic Potential |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amino Acid Derivatives | Phenylacetylglutamine, p-cresol-glucuronide, indole-acetate [2] | Compromised glucose homeostasis, Type 2 Diabetes [2] | Predictive biomarkers for metabolic disease progression and treatment response |

| Xenobiotics | Benzoate derivatives, compounds in xanthine/caffeine metabolism [2] | Reflection of dietary habits and microbial adaptation [2] | Indicators of dietary exposure and personalized metabolic profiles |

| Lipid Metabolites | Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and other lipid species [1] [2] | Immune regulation, gut barrier integrity, energy metabolism [1] | Biomarkers for inflammatory states and cardiometabolic health |

| Microbial Biosynthetic Products | Molecules from unexplored Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs) [3] | Disease-specific associations across body sites [3] | Novel diagnostic signatures and therapeutic targets |

Experimental Protocol: Metabolome-Wide Association Study (MWAS)

Objective: To identify and validate plasma metabolites associated with the gut microbiome and a specific disease phenotype (e.g., impaired glucose control) [2].

Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions: EDTA plasma collection tubes; LC-MS/MS system with electrospray ionization; Human Metabolome Database (HMDB) for annotation; GBDT/random forest machine learning environments (e.g., R, Python with scikit-learn); Germ-free (GF) and conventionally raised (CONV-R) mouse models [2].

Procedure:

- Cohort Establishment & Sampling: Recruit a well-phenotyped patient cohort, ensuring representation across disease states (e.g., normal glucose tolerance, prediabetes, treatment-naive T2D) and BMI-matching where appropriate to control for confounding [2]. Collect plasma samples using standardized protocols and store at -80°C.

- Metabolomic Profiling: Perform untargeted metabolomic profiling on plasma samples using Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS). Annotate metabolites against reference databases (e.g., HMDB). The resulting data matrix should contain samples as rows and metabolite relative abundances as columns [2].

- Predictive Modeling of Metabolite Variance: Use a Gradient-Boosted Decision Trees (GBDT) algorithm to model the relationship between feature groups (clinical data, microbial metagenomic species, dietary variables) and each circulating metabolite. Quantify the variance explained (R²) by each feature group to identify microbiome-associated metabolites (e.g., those where microbiome data explains a significant portion of variance) [2].

- Cross-Platform and Cross-Population Validation:

- Technical Validation: Process raw metagenomic data through multiple bioinformatic pipelines (e.g., reference-free canopy clustering, Kraken 2, MetaPhlAn 4) and confirm that microbiome-metabolite associations are consistent across pipelines (Pearson correlation >0.95) [2].

- Population Validation: Replicate significant microbiome-metabolite associations in an independent cohort from a different geographical population (e.g., Swedish findings in an Israeli cohort) [2].

- In Vivo Validation: Measure the identified microbiome-associated metabolites in plasma from GF and CONV-R mice. Confirm that a significant proportion (e.g., >50%) of these metabolites are depleted or altered in GF mice, providing causal evidence of their microbial origin [2].

Therapeutic Strategies for Microbiome Modulation

Therapeutic manipulation of the microbiome presents a promising avenue for treating a wide range of conditions. Current strategies range from entire community transplantation to precisely targeted interventions.

Table 2: Therapeutic Modalities for Microbiome Modulation

| Therapeutic Modality | Description | Key Examples | Clinical Stage/Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) | Transfer of minimally processed donor stool to restore a healthy microbial community [4]. | Treatment for recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection [4]. | Regulatory oversight is evolving; variable efficacy; risk of pathogen transfer [4]. |

| Live Biotherapeutic Products (LBPs) | Defined bacterial strains administered as drugs [1] [4]. | Akkermansia muciniphila (metabolic health), Faecalibacterium prausnitzii (Crohn's disease) [4]. | Require Investigational New Drug (IND) application; complex manufacturing (CMC) [4]. |

| Phage Therapy | Use of bacteriophage cocktails to selectively target and suppress disease-contributing pathobionts [1] [4]. | Cocktails targeting Klebsiella pneumoniae strains in IBD [1] [4]. | First-in-human trials show viability and safety; requires careful cocktail design to prevent resistance [4]. |

| Precision Nutrition | Dietary interventions tailored to an individual's microbiome to modulate its composition and function [1] [2]. | Interventions based on personalized microbiome-metabolite profiles to improve glucose control [2]. | High personalization potential; integrates with other omics data for "biological BMI" [4]. |

| Defined Microbial Consortia | Synthetically assembled communities of known bacterial strains [4]. | Complex defined consortia (>100 strains) for reliable engraftment and diverse metabolic functions [4]. | Designed to overcome FMT variability; highly engineerable but face engraftment challenges [4]. |

Experimental Protocol: Phage Cocktail Preparation and Administration for Targeted Pathobiont Suppression

Objective: To develop and test an orally administered bacteriophage cocktail for the targeted suppression of a specific disease-contributing pathobiont (e.g., Klebsiella pneumoniae in Inflammatory Bowel Disease) [4].

Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions: Bacterial isolates of the target pathobiont from patient cohorts; environmental phage libraries or clinical samples for phage isolation; cell culture materials for phage propagation (host bacteria, growth media, filters); germ-free or gnotobiotic mouse models; capsule-based oral delivery system for phages [4].

Procedure:

- Target Identification & Phage Isolation: Identify a specific pathobiont clade consistently expanded in patient cohorts (e.g., K. pneumoniae clade 2 in IBD) [4]. Isolate bacteriophages that infect this target by enriching environmental or clinical samples with the bacterial strain. Isolate individual plaques and purify through successive streaking.

- Phage Cocktail Design: Select at least 3-4 phages that attack the same bacterial strain but utilize different host receptors for entry. This multi-receptor strategy is critical to minimize the development of phage resistance in the target bacterium [4].

- In Vitro Efficacy and Specificity Testing: Test the phage cocktail's efficacy in killing the target pathobiont in vitro. Co-culture the phage cocktail with human fecal samples ex vivo to confirm target suppression and assess off-target effects on the rest of the microbial community, aiming for minimal dysbiosis [4].

- Preclinical Animal Testing: Administer the phage cocktail orally to germ-free mice that have been humanized with the target pathobiont or to gnotobiotic models. Monitor phage viability through the GI tract, target bacterial load reduction, and markers of inflammation and tissue damage to establish proof-of-concept [4].

- Clinical Trial Formulation and Testing: For human trials, formulate phages in a capsule resistant to gastric acid to ensure delivery to the lower gut. A first-in-human Phase I clinical trial should first establish the safety and viability of the phages in the human gastrointestinal tract before proceeding to efficacy studies for the disease indication [4].

Essential Methodologies and Reporting Standards

Robust and reproducible microbiome science requires standardized methodologies from the bench to computational analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Essential Tools for Microbiome Research and Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Tool / Solution | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing & Profiling | Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing [3] [5] | Provides a comprehensive view of all genetic material, allowing for taxonomic and functional profiling. |

| LC-MS/MS Metabolomics Platform [2] | Identifies and quantifies small molecule metabolites in biofluids, linking microbial function to host phenotype. | |

| Bioinformatic Analysis | iNAP (Integrated Network Analysis Pipeline) [6] | Online pipeline for constructing and analyzing intra- and inter-domain microbial ecological networks from abundance data. |

| SparCC, SPIEC-EASI, eLSA [6] | Statistical methods within iNAP and other tools to infer robust microbial associations from compositional data. | |

| Reporting Framework | STORMS Checklist [7] | A 17-item checklist for organizing and reporting microbiome studies to ensure completeness and reproducibility. |

| Reference Materials | Human Fecal Reference Material [4] | Standardized reference material (e.g., from NIST) to control for technical bias in sample processing and sequencing. |

| Experimental Models | Germ-Free (GF) Mouse Models [2] | In vivo models to conclusively demonstrate the microbial origin of specific metabolites or physiological effects. |

Experimental Protocol: Standardized Metagenomic Sequencing and Reporting

Objective: To generate high-quality, reproducible metagenomic data from human specimens and report it in accordance with community standards [7] [3].

Materials: Specimen collection kits (e.g., stool, saliva, skin swabs); DNA extraction kits optimized for microbial lysis; library preparation kits; high-throughput sequencer (e.g., Illumina); STORMS checklist [7].

Procedure:

- Standardized Sample Collection and Biobanking: Collect specimens from multiple body sites (e.g., stool, saliva, plaque, skin, throat) using a standardized protocol across all recruiting sites [3]. Immediately freeze samples at -80°C, as this preservation method is considered most appropriate for maintaining microbiome integrity [4].

- DNA Extraction and Sequencing: Extract DNA using a method that efficiently lyses both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Perform shotgun metagenomic library preparation and sequence to a sufficient depth (e.g., an average of 5.3 gigabases per sample) to achieve comprehensive coverage [3].

- Quality Control and Human DNA Depletion: Apply stringent quality control to raw sequencing data. Remove reads that align to the human genome to reduce host contamination and protect patient privacy. Retain only high-quality metagenomes for downstream analysis [3].

- Taxonomic and Functional Profiling: Process non-human sequencing reads through a standardized bioinformatic pipeline for taxonomic binning (e.g., to Species-level Genome Bins - SGBs) and functional annotation (e.g., of Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes orthologies and Biosynthetic Gene Clusters) [2] [3].

- Compliant Study Reporting: During manuscript preparation, use the STORMS checklist to ensure all critical elements are reported [7]. This includes detailed descriptions of participants (including geography and diet), specimen collection dates, DNA extraction and sequencing methods, bioinformatic tools and parameters, and statistical approaches used for association testing.

Integrated Workflow and Analytical Pipelines

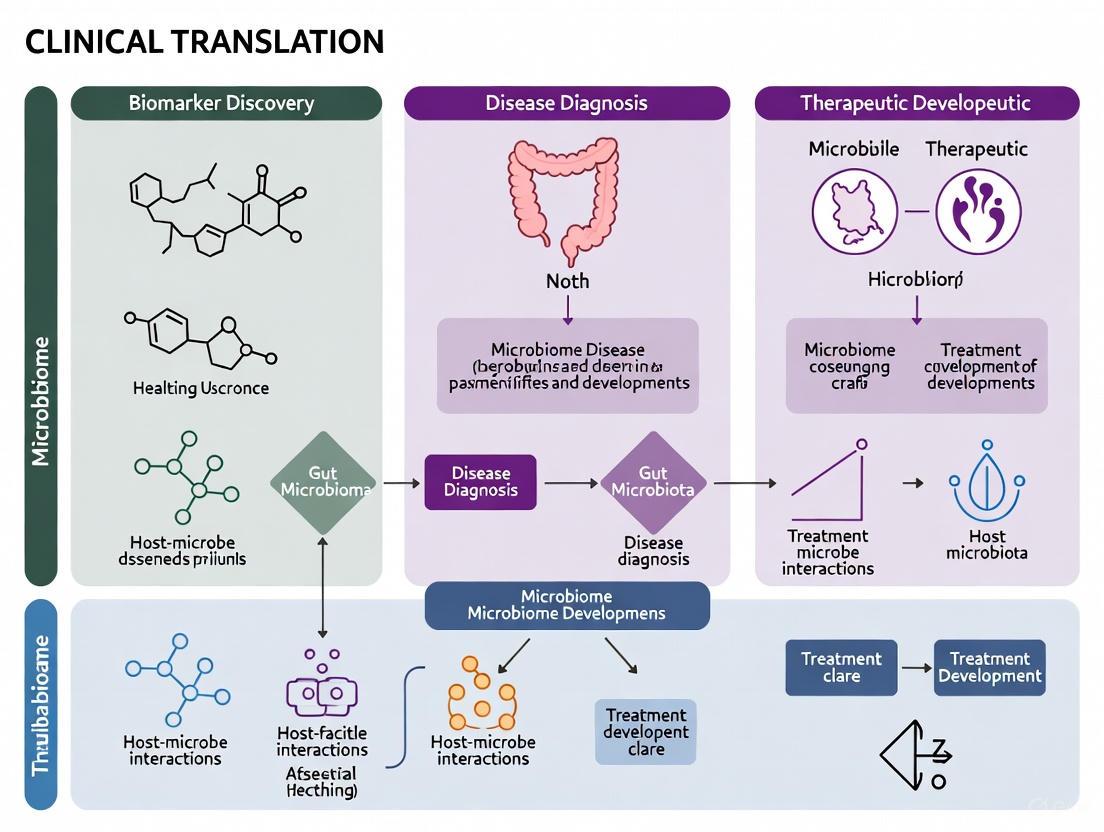

The following diagram illustrates the integrated multi-omics workflow for discovering and validating microbiome-based diagnostic and therapeutic targets, from initial sampling to clinical application.

Integrated Workflow for Microbiome Research and Translation

This integrated workflow underscores the necessity of combining standardized multi-omic data generation with advanced computational modeling and rigorous validation to successfully translate microbiome research into clinical applications [1] [2] [3]. The pathway highlights key stages from initial sampling through to the discovery of diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets, culminating in clinical trials governed by regulatory standards [4].

The human microbiome, a complex ecosystem of microorganisms, is now recognized as a dynamic and essential determinant of human physiology, shaping immunity, metabolism, neurodevelopment, and therapeutic responsiveness across the lifespan [1]. The clinical translation of microbiome science represents a paradigm shift in precision medicine, transforming concepts of disease etiology and therapeutic design [1]. This Application Note delineates the key mechanistic pathways—immune signaling, metabolic interactions, and host-microbe crosstalk—underpinning microbiome-host symbiosis and its translational applications. We provide detailed experimental frameworks and analytical protocols to facilitate research in microbiome diagnostics and therapeutic development.

Key Mechanistic Pathways in Microbiome-Host Interactions

Immune Signaling Pathways

The immune system and microbiome engage in continuous, bidirectional communication critical for maintaining homeostasis and mounting appropriate responses to challenges [8]. Microbial communities play a fundamental role in training and developing both innate and adaptive immunity, while the immune system orchestrates the maintenance of host-microbe symbiosis [8].

Table 1: Key Microbial Modulators of Host Immune Signaling

| Microbial Component | Immune Receptor | Downstream Signaling | Biological Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polysaccharide A (PSA) from Bacteroides fragilis | TLR2/TLR1 with Dectin-1 | PI3K pathway → GSK3β inactivation → CREB activation [8] | Anti-inflammatory gene expression; systemic T cell maturation [8] |

| Segmented Filamentous Bacteria (SFB) antigens | Not specified (epithelial adhesion) | STAT3 signaling → RORγt activation [8] | Th17 cell differentiation in small intestine lamina propria [8] |

| Microbial metabolites (SCFAs) | GPR43, GPR109A | Inhibition of HDACs; NF-κB modulation [9] [8] | Treg differentiation; anti-inflammatory effects; barrier integrity [9] [8] |

| Flagellin | TLR5 | MyD88/NF-κB signaling [8] | Innate immune activation; microbiota composition shaping [8] |

Diagram Title: Microbiome-Mediated Immune Signaling Pathway

Metabolic Interactions and Cross-Feeding

Metabolism forms the central pillar of host-microbe relationships, with microbial metabolites serving as crucial signaling molecules and energy sources [9]. The intestinal epithelium and gut microbiota maintain a cyclical relationship of mutual metabolic benefit—host epithelial metabolism provides a hypoxic niche for obligate anaerobes, while microbial metabolites like butyrate serve as the primary energy source for colonocytes [9].

Table 2: Key Microbial Metabolites and Host Functions

| Metabolite | Producing Microbes | Host Receptor/Target | Biological Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Butyrate | Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Roseburia spp. | HDACs; PPARγ [9] | Primary colonocyte energy source; maintenance of hypoxic lumen; anti-inflammatory [9] |

| Acetate | Bifidobacterium spp., Bacteroides spp. | GPR43 [9] | Substrate for butyrogenesis; cholesterol metabolism; anti-inflammatory [9] |

| Propionate | Bacteroides spp., Akkermansia spp. | GPR41, GPR43 [9] | Gluconeogenesis; satiety signaling; immune regulation [9] |

| Lactate | Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) | GPR81 [9] | Intestinal stem cell differentiation via Wnt signaling; epithelial repair [9] |

| Indolepropionic acid (IPA) | Clostridium sporogenes | Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) [9] | Enhancement of epithelial barrier function [9] |

Diagram Title: Host-Microbe Metabolic Cross-Feeding Cycle

Host-Microbe Crosstalk in Disease and Therapeutics

Imbalances in microbiota-immunity interactions contribute to pathogenesis across a spectrum of disorders, including inflammatory bowel disease, metabolic syndrome, cancer, and neurodegenerative diseases [8] [10] [11]. The microbiota-gut-brain axis represents a particularly important regulatory system where microbial metabolites and neuroactive compounds influence glial function and neuroinflammation [11].

Table 3: Microbiome-Based Therapeutic Strategies and Mechanisms

| Therapeutic Approach | Mechanism of Action | Target Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) | Restoration of diverse microbial community; niche competition [12] | Recurrent C. difficile infection; IBD; hepatic encephalopathy [12] |

| Probiotics (single or multi-strain) | Direct microbial antagonism; barrier enhancement; immunomodulation [12] | NEC in preterm infants; immune dysregulation; metabolic disorders [1] [12] |

| Prebiotics (HMOs, fiber) | Selective stimulation of beneficial microbes; SCFA production [1] | Infant development; metabolic syndrome; inflammatory conditions [1] |

| Phage Therapy | Targeted elimination of pathogenic bacteria [1] | Antibiotic-resistant infections; inflammatory bowel disease [1] |

| Engineered Live Biotherapeutics | Delivery of therapeutic molecules (e.g., immunomodulators, enzymes) [12] | Metabolic disorders; cancer; autoimmune diseases [12] |

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Host-Microbe Interactions

Protocol: Gnotobiotic Mouse Model for Microbiome-Function Studies

Purpose: To establish causal relationships between specific microbial taxa and host physiological responses using germ-free (GF) mouse models.

Materials:

- Germ-free isolators and housing equipment

- Sterilized food, water, and bedding

- Anaerobic chamber for microbial culture

- Specific pathogen-free (SPF) or defined microbial consortia

- DNA/RNA extraction kits

- Metabolomic analysis equipment (LC-MS, GC-MS)

Procedure:

- Animal Preparation: House GF mice in flexible film isolators with sterilized diet and water ad libitum.

- Microbial Inoculation:

- Prepare defined microbial consortium in anaerobic chamber under strict oxygen-free conditions.

- Administer 200μL of bacterial suspension (10^9 CFU/mL) via oral gavage to 6-8 week old GF mice.

- Include control groups: GF (no inoculation) and SPF (complex microbiota) controls.

- Monitoring and Sampling:

- Collect fecal samples at days 0, 3, 7, 14, 21 post-inoculation for microbial analysis.

- Monitor body weight, food intake, and behavioral parameters daily.

- Tissue Collection:

- At endpoint, euthanize mice and collect intestinal tissues, mesenteric lymph nodes, liver, and blood.

- Preserve tissues for: (i) flow cytometry (RPMI medium), (ii) gene expression (RNA later), (iii) histology (formalin fixation).

- Analysis:

- Verify microbial colonization via 16S rRNA sequencing and qPCR.

- Assess immune cell populations by flow cytometry (focus on Treg, Th17, dendritic cells).

- Measure metabolite profiles in cecal content and serum by LC-MS/GC-MS.

- Evaluate epithelial barrier function (Ussing chamber) and gene expression (RNA-seq).

Applications: This protocol enables researchers to determine causal mechanisms of specific microbes on host immunity, metabolism, and disease susceptibility [8].

Protocol: Flux Balance Analysis for Host-Microbe Metabolic Modeling

Purpose: To predict metabolic interactions between host and microbiota using constraint-based modeling approaches.

Materials:

- Genome-scale metabolic reconstructions (e.g., Recon3D for human, AGORA for microbes)

- COBRA Toolbox or similar metabolic modeling software

- High-performance computing resources

- Bacterial genome annotations

- Physiological constraint data (dietary intake, metabolic fluxes)

Procedure:

- Model Reconstruction:

- Obtain genome-scale metabolic reconstruction for host (Human1 or Recon3D) and microbial species of interest.

- For unannotated microbes, use ModelSEED or RAVEN toolbox for draft reconstruction.

- Network Integration:

- Create a compartmentalized model with separate spaces for: host cytosol, microbial cytosol, and gut lumen.

- Define metabolite exchange reactions between compartments.

- Set appropriate constraints for reaction fluxes based on physiological data.

- Simulation Setup:

- Define objective functions (e.g., maximize biomass production, maximize ATP yield, or maximize butyrate production).

- Apply dietary constraints based on experimental conditions.

- Implement parsimonious enzyme usage FBA (pFBA) to obtain realistic flux distributions.

- Simulation and Analysis:

- Perform flux balance analysis to predict metabolic fluxes under steady-state conditions.

- Conduct gene essentiality analysis by simulating single gene knockouts.

- Predict community metabolic output with different microbial compositions.

- Validate predictions with experimental metabolomics data.

Applications: FBA enables prediction of metabolic dependencies in host-microbe systems, identification of essential nutrients, and simulation of dietary or therapeutic interventions [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Microbiome-Host Interaction Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Gnotobiotic Models | Germ-free mice; OMM^12 mice; Altered Schaedler Flora | Controlled colonization studies; causal mechanism investigation [8] |

| Cell Culture Systems | Organoids; transwell epithelial systems; co-culture models | Barrier function studies; host-microbe interface modeling [1] |

| Sequencing Reagents | 16S rRNA primers (V3-V4); metagenomic library preps; RNA-seq kits | Microbial community profiling; functional potential assessment [14] |

| Metabolomics Standards | SCFA standards; bile acids; tryptophan metabolites; internal standards | Quantification of microbial metabolites in biological samples [9] [13] |

| Immunological Assays | ELISA for IgA, cytokines; flow cytometry antibodies (CD4, CD8, Treg panels) | Immune phenotyping; mucosal immunity assessment [8] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | QIIME 2; PICRUSt2; MetaPhlAn; HUMAnN; COBRA Toolbox | Microbiome data analysis; metabolic modeling [13] [14] |

The mechanistic understanding of immune signaling, metabolic interactions, and host-microbe crosstalk provides a robust foundation for developing microbiome-based diagnostics and therapeutics. The experimental protocols and research tools outlined herein enable systematic investigation of these mechanisms, accelerating the translation of microbiome science into clinical applications. As the field advances, integrating multi-omics data with computational models will be essential for personalizing microbiome-targeted interventions and realizing the full potential of microbiome medicine.

The human microbiome, particularly the gut microbiota, functions as a virtual endocrine organ that is essential for maintaining host homeostasis. Dysbiosis, defined as an imbalance in the microbial community structure, has been implicated in a vast spectrum of diseases through complex crosstalk along the gut-brain-immune axis [15] [16]. The clinical translation of microbiome science represents a paradigm shift in understanding disease etiology, introducing innovative diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for gastrointestinal, metabolic, immune, and neurological disorders [1] [17]. This application note synthesizes current evidence and provides structured protocols for investigating dysbiosis across disease contexts, framed within the broader thesis of advancing microbiome clinical translation for diagnostic and therapeutic applications.

Quantitative Associations Between Dysbiosis and Disease

Table 1: Gut Microbiota Alterations in Autoimmune Neurological Diseases (Meta-Analysis Findings)

| Disease Category | α-Diversity (Chao1 Index) | Key Bacterial Changes (Decreased) | Key Bacterial Changes (Increased) | Consistent β-Diversity Changes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autoimmune Encephalitis (AIE) | Small decrease (SMD = -0.26) | Faecalibacterium, Roseburia | Streptococcus, Escherichia-Shigella | Inconsistent across studies |

| Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorders (NMOSD) | Small decrease (SMD = -0.26) | Faecalibacterium, Roseburia | Streptococcus, Escherichia-Shigella | Consistent differences observed |

| Myasthenia Gravis (MG) | Small decrease (SMD = -0.26) | Faecalibacterium, Roseburia | Streptococcus, Escherichia-Shigella | Inconsistent across studies |

| Multiple Sclerosis (MS) | Small decrease (SMD = -0.26) | Faecalibacterium, Roseburia | Streptococcus, Escherichia-Shigella | Inconsistent across studies |

| Healthy Controls | Reference range | High SCFA-producing bacteria | Low pathogenic bacteria | Reference community structure |

Data derived from systematic review and meta-analysis of 62 studies (n=3,126 patients, n=2,843 controls) [18]

Table 2: Dysbiosis-Associated Functional Metabolite Changes in Disease

| Disease Category | SCFA Production | Bile Acid Metabolism | Neuroactive Metabolites | Inflammatory Mediators |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GI Dysmotility (IBS/SIBO) | Decreased butyrate | Altered deconjugation | Serotonin imbalance | Increased LPS, TNF-α |

| Metabolic Disorders (T2D) | Decreased butyrate | Impaired signaling | GABA/5-HT alterations | Low-grade inflammation |

| Neurodegenerative (AD/PD) | Significantly reduced | Dysregulated | Dopamine/GABA deficits | IL-6, IL-1β elevation |

| Autoimmune Neurological | Reduced (Faecalibacterium) | Not reported | Not reported | Systemic inflammation |

| Drug-Induced Brain Injury | Depleted butyrate | Not reported | Serotonin, dopamine disruption | Oxidative stress, ROS |

SCFAs: Short-chain fatty acids; LPS: Lipopolysaccharide; ROS: Reactive oxygen species; Data compiled from multiple sources [15] [16] [19]

Experimental Protocols for Dysbiosis Research

Protocol: Multi-Omic Profiling of Gut Microbiota in Disease Cohorts

Application: Comprehensive characterization of microbial dysbiosis in patient populations for biomarker discovery and mechanistic insights.

Materials and Reagents:

- Stool collection kits (DNA/RNA stabilizer)

- DNA extraction kits (e.g., QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit)

- Library preparation reagents (Illumina compatible)

- LC-MS/MS equipment for metabolomics

- Bioinformatics pipelines (QIIME 2, LEfSe, MetaPhlAn)

Procedure:

- Patient Recruitment and Stratification: Recruit well-characterized patient cohorts and matched controls. Record clinical metadata, disease activity, medication use, and dietary patterns.

- Sample Collection and Preservation: Collect fresh stool samples using standardized collection kits with DNA/RNA stabilizers. Aliquot samples for various analyses and store at -80°C.

- DNA Extraction and Quality Control: Perform standardized DNA extraction with bead beating for mechanical lysis. Verify DNA quality and quantity using spectrophotometry and gel electrophoresis.

- Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing: Prepare sequencing libraries targeting 20-50 million reads per sample. Sequence on Illumina platform (2x150bp). Include positive and negative controls.

- Metabolomic Profiling: Extract metabolites using methanol:water:chloroform. Analyze SCFAs, bile acids, and tryptophan metabolites via LC-MS/MS with internal standards.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Process sequencing data through quality filtering, host DNA removal, and taxonomic profiling. Conduct functional annotation (KEGG, MetaCyc). Integrate with metabolomic data using multivariate statistics.

- Validation: Confirm key findings using qPCR for specific bacterial taxa or targeted metabolomics in independent validation cohort.

Quality Controls: Include extraction blanks, positive control communities (ZymoBIOMICS), and sample replicates to monitor technical variability [18] [4] [20].

Protocol: Assessing Gut-Brain Axis Communication in Preclinical Models

Application: Mechanistic investigation of microbiota-host interactions in neurological disorders.

Materials and Reagents:

- Germ-free or gnotobiotic mouse models

- Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) equipment

- Behavioral testing apparatus

- Immunoassay kits for cytokines

- Tissue processing reagents for histology

Procedure:

- Model Establishment: Use germ-free mice or antibiotic-treated specific pathogen-free mice to create manipulated microbiota states.

- Fecal Microbiota Transplantation: Prepare donor inoculum from human patients or characterized mouse models. Administer via oral gavage to recipient mice (200μL daily for 3 days).

- Behavioral Phenotyping: Conduct standardized tests at consistent time points: open field (anxiety), forced swim (depression-like), Y-maze (cognition), and motor coordination tests.

- Tissue Collection and Processing: Collect brain, gut, and blood samples. Perfuse animals with PBS before tissue collection for optimal preservation.

- Immunological Profiling: Measure cytokine levels (IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β) in plasma and brain homogenates using ELISA or multiplex assays. Analyze immune cell populations in brain and gut by flow cytometry.

- Blood-Brain Barrier Assessment: Evaluate BBB integrity using Evans Blue extravasation and tight junction protein expression (claudin-5, occludin) via immunohistochemistry.

- Histopathological Analysis: Examine brain sections for microglial activation (Iba1 staining), neuronal damage, and pathological protein aggregation.

Validation: Confirm microbial engraftment via 16S rRNA sequencing of recipient fecal samples. Correlate behavioral changes with microbial and immunological parameters [21] [19] [20].

Signaling Pathways in Microbiota-Host Communication

Figure 1: Gut-Brain-Immune Axis Signaling in Dysbiosis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Microbiome-Disease Research

| Research Tool | Application | Specific Examples | Function in Experimental Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Stabilization Kits | Sample preservation | DNA/RNA Shield, RNAlater | Maintains nucleic acid integrity during storage and transport |

| Metagenomic Kits | Community profiling | QIAamp PowerFecal Pro, DNeasy PowerSoil | Comprehensive DNA extraction from complex samples |

| SCFA Standards | Metabolite quantification | Acetate, propionate, butyrate reference standards | Quantification of key microbial metabolites via LC-MS/MS |

| Cytokine Panels | Immune profiling | Luminex multiplex assays, ELISA kits | Measurement of inflammatory mediators in serum and tissues |

| Gnotobiotic Models | Mechanistic studies | Germ-free mice, Humanized microbiota mice | Establish causal relationships between microbiota and disease |

| Biotherapeutic Strains | Intervention studies | Akkermansia muciniphila, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii | Test therapeutic potential of specific commensals |

| Phage Cocktails | Targeted depletion | Klebsiella pneumoniae-targeting phages | Selective elimination of pathobionts |

| Tight Junction Antibodies | Barrier integrity | Anti-occludin, anti-claudin-5 | Assess gut and blood-brain barrier function |

Compiled from experimental methodologies across cited references [21] [18] [4]

The systematic investigation of dysbiosis across gastrointestinal, metabolic, immune, and neurological disorders reveals both shared and disease-specific alterations in microbial communities and their functional outputs. The quantitative data and standardized protocols provided in this application note establish a framework for advancing microbiome research from associative studies to mechanistic investigations and therapeutic applications. As the field moves toward clinical translation, rigorous experimental design, standardized methodologies, and multi-modal data integration will be essential for developing microbiome-based diagnostics and therapeutics that can be implemented in routine clinical care [17] [22]. The continued elucidation of microbiota-host signaling pathways will undoubtedly yield novel therapeutic targets for a wide spectrum of dysbiosis-associated diseases.

The initial colonization and subsequent development of the gut microbiome during early life represent a critical developmental window with profound implications for long-term health. Early-life gut microbiome (GM) development plays a pivotal role in shaping the immune system, developing the intestinal tract, and influencing host metabolism [23]. This process is strongly influenced by several determinants, including gestational age at birth, mode of delivery, neonatal feeding practices, early-life stress, and exposure to perinatal antibiotics [23]. The establishment of the GM after birth evolves throughout the host's lifespan, from infancy to advanced age, ultimately achieving homeostasis through complex ecological and trophic interrelationships between microbial members and the human host [23]. However, disruptions during this critical period through GM dysbiosis may alter developmental programming, leading to long-term adverse health outcomes including allergic diseases, metabolic disorders, type 1 diabetes, inflammatory bowel disorders, and atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases [23]. This Application Note provides a comprehensive framework for investigating early-life microbiome development, with standardized protocols and analytical tools to advance research in microbiome clinical translation, diagnostics, and therapeutic applications.

Foundational Concepts and Determinants

The establishment of the neonatal gut microbiome commences through maternal microbial transmission, with recent evidence challenging the historical "sterile womb paradigm" [23]. While the intrauterine environment remains a subject of scientific debate, substantial microbial colonization occurs during and immediately after birth, primarily sourced from maternal gut, vaginal, and placental reservoirs [24]. Microbial source-tracking analyses using algorithms like FEAST indicate that the maternal gut and placenta serve as major contributors to neonatal meconium colonization, with gut-derived input increasing over time [24].

Early microbial succession patterns demonstrate remarkable conservation across diverse human populations, suggesting universal developmental trajectories [25]. Large-scale meta-analyses of 3,154 shotgun-sequenced samples from 1,827 infants across 12 countries reveal that gut microbial taxonomic profiles can predict infant age with high temporal resolution (±3 months) for the first 1.5 years of life [25]. This predictable succession pattern provides a normative benchmark of "microbiome age" for assessing gut maturation alongside other measures of child development.

Table 1: Key Determinants of Early-Life Microbiome Development

| Determinant Category | Specific Factors | Impact on Microbiome Composition | Long-Term Health Associations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perinatal Factors | Mode of delivery (vaginal vs. cesarean) | Alters initial microbial inoculum; vaginal delivery provides maternal vaginal and fecal microbes | Immune-mediated diseases; metabolic disorders |

| Gestational age at birth | Preterm birth associated with delayed colonization and reduced diversity | Neurodevelopmental impairments; necrotizing enterocolitis | |

| Maternal microbiome status | Determines microbial sources available for vertical transmission | Allergic diseases; immune programming | |

| Postnatal Exposures | Feeding practices (breastfeeding vs. formula) | Breastfeeding promotes Bifidobacterium; formula feeding increases diversity earlier | Immune development; metabolic programming |

| Antibiotic exposure | Reduces microbial diversity and SCFA production; promotes antimicrobial resistance | Allergic diseases; obesity; neurodevelopmental conditions | |

| Early-life stress | Reduces key SCFA-producing taxa; alters microbiome metabolic output | Mental health disorders; inflammatory diseases | |

| Interventions | Probiotic supplementation | Transiently alters composition; enhances microbial stability | Reduced eczema incidence; improved immune markers |

| Prebiotic supplementation | Promotes growth of beneficial taxa (Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus) | Enhanced gut barrier function; immune modulation |

Quantitative Models and Normative Benchmarks

The development of quantitative models for gut microbiome maturation provides powerful tools for assessing normative development and identifying deviations associated with disease states. Recent research has established a random forest model using gut microbial taxonomic relative abundances from metagenomes that achieves high temporal resolution (±3 months) for the first 1.5 years of life, with a root mean square error of 2.56 months [25]. This model was trained on 3,154 samples from 1,827 infants across 12 countries, demonstrating conserved microbial succession patterns across diverse populations [25].

Key taxonomic predictors of microbiome age include declines in Bifidobacterium spp. and increases in Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Lachnospiraceae species [25]. Alpha-diversity, measured as the Shannon index, serves as the third most important predictor (4.86% of total importance, R(age) = +0.52) [25]. These patterns reflect feeding transitions and dietary exposures, with functional analysis confirming trends in key microbial genes involved in these developmental milestones.

Table 2: Key Taxonomic Predictors of Microbiome Age in Early Development

| Taxonomic Predictor | Direction with Age | Relative Importance | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Faecalibacterium prausnitzii | Positive | High (17.3% combined with A. hadrus) | Butyrate production; anti-inflammatory properties |

| Anaerostipes hadrus | Positive | High (17.3% combined with F. prausnitzii) | SCFA production; metabolic health |

| Bifidobacterium longum | Negative | 2.2% combined with B. breve | Human milk oligosaccharide metabolism; immune modulation |

| Bifidobacterium breve | Negative | 2.2% combined with B. longum | Early gut colonizer; probiotic candidate |

| Lachnospiraceae species | Positive | Variable | Plant polysaccharide digestion; SCFA production |

| Dorea longicatena | Positive | Variable | Geographic variation; elevated in South African cohorts |

| Escherichia coli | Variable | Variable | Elevated in Brazilian cohorts; potential pathobiont |

| Shannon α-diversity | Positive | 4.86% | Overall community richness and evenness |

Mechanistic mathematical models representing the interplay between gut ecology and adaptive immunity provide insights into the ontogeny of immune tolerance [26]. These models integrate exogenous inputs into the gut lumen with endogenous dynamics in the gut lumen and organized gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) inductive sites. Such frameworks formalize the concept of 'immune education' during early life, enabling exploration of diagnostic markers, clinical intervention strategies, and preventive measures before pathological trajectories are imprinted [26].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Longitudinal Microbiome Sampling in Neonatal Populations

Application: This protocol standardizes the collection, processing, and storage of neonatal microbiome samples for longitudinal studies, enabling robust multi-omics integration.

Materials:

- Sterile fecal collection kits with nucleic acid preservatives (e.g., RNA/DNA Shield)

- Vaginal swab kits (e.g., ESwab collection system)

- Placental tissue collection: sterile surgical scissors, scalpels, cryovials

- DNA/RNA-free consumables

- -80°C freezer or liquid nitrogen storage system

Procedure:

- Maternal Sample Collection:

- Collect maternal fecal samples (1-2 g) in 50 mL centrifuge tubes during defecation

- Obtain vaginal samples by trained professionals using sterile swabs

- Collect placental tissue within 10 minutes of delivery under strict aseptic conditions

Neonatal Sample Collection:

- Collect meconium (day 1) and fecal samples (days 3, 14, and longitudinally through 6 months)

- For preterm infants in NICU settings, consider daily sampling when possible

- Aliquot samples at source when immediate cold chain unavailable

Sample Processing:

- Extract genomic DNA using CTAB/SDS method or commercial kits

- Assess DNA purity and concentration by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis

- Amplify V3-V4 hypervariable region of 16S rRNA gene using primers 341F/806R

- Perform library construction using Ion Plus Fragment Library Kit

- Sequence on Ion S5 XL platform or comparable system

Quality Control:

- Include no-template controls during amplification

- Monitor for contamination through extraction blanks

- Rarefy to even sequencing depth (minimum 5,338 reads/sample) for diversity analyses [24]

Analytical Workflow:

- Process sequence data through standardized bioinformatics pipeline (e.g., BioBakery V3) [25]

- Cluster sequences into OTUs at 97% similarity threshold using UPARSE

- Perform taxonomic annotation using Silva Database via Mothur

- Conduct microbial source tracking using FEAST algorithm

- Integrate with metabolomic and proteomic data for multi-omics analysis

Protocol: Probiotic Intervention during Pregnancy and Early Infancy

Application: Evaluate the impact of prenatal and early-life probiotic supplementation on maternal-to-neonatal microbial transmission and infant gut development.

Materials:

- Probiotic formulation (e.g., Bifidobacterium longum, Lactobacillus delbrueckii bulgaricus, Streptococcus thermophilus)

- Placebo tablets identical in appearance

- Standardized dietary record forms

- Compliance assessment tools (pill counts, participant diaries)

Procedure:

- Participant Recruitment:

- Recruit pregnant women before 32nd gestational week

- Apply inclusion criteria: singleton pregnancy, first-time pregnancy, gestational age ≥37 weeks at delivery

- Exclude participants with regular probiotic/prebiotic consumption, antibiotic use, or pregnancy complications

Randomization and Intervention:

- Randomize participants to probiotic or control group

- Administer probiotic supplement (e.g., Golden Bifid tablets) twice daily from gestational week 32 until delivery

- Control group receives no intervention or placebo

- Monitor for gastrointestinal symptoms and assess compliance through returned packaging

Sample Collection and Analysis:

- Collect maternal fecal, vaginal, and placental samples at full term

- Obtain neonatal fecal samples longitudinally (days 1, 3, 14, 6 months)

- Perform 16S rRNA gene sequencing and microbial community profiling

- Conduct volatility analysis to assess microbial stability

- Perform source-tracking analysis using FEAST algorithm

Outcome Measures:

- Alpha and beta diversity metrics of neonatal meconium microbiota

- Relative contributions of maternal microbial sources to neonatal gut colonization

- Microbial stability during early colonization period (days 1-3)

- Persistence of intervention effects through 6 months postpartum

Signaling Pathways and Mechanistic Insights

The gut-brain axis represents a critical signaling network through which the early-life microbiome influences neurodevelopment, particularly in vulnerable preterm populations. Five primary mechanistic pathways link microbial disturbances to adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes: (1) immune activation and white matter injury; (2) short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs)-mediated neuroprotection; (3) tryptophan-serotonin metabolic signaling; (4) hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis modulation; and (5) integrity of intestinal and blood-brain barriers [27].

Diagram 1: Gut-Brain Axis Signaling Pathways in Early-Life Neurodevelopment. This diagram illustrates the primary mechanistic pathways through which early-life microbiome disruptions influence neurodevelopmental outcomes, particularly in preterm infants.

The immune-mediated pathway involves microbiome-driven activation of systemic immune responses that can lead to white matter injury in the developing brain [27]. SCFAs, including acetate, propionate, and butyrate, serve as crucial microbial metabolites that exert neuroprotective effects through multiple mechanisms, including histone deacetylase inhibition and support of mitochondrial function [28] [27]. The tryptophan-serotonin pathway demonstrates how microbial metabolism influences neurotransmitter systems critical for mood, cognition, and behavior [27]. Early-life stress and dysbiosis can persistently alter HPA axis function, affecting stress responsiveness and emotional regulation throughout life [28]. Finally, microbiome composition directly influences the integrity of both intestinal and blood-brain barriers, potentially permitting increased translocation of inflammatory mediators into the CNS [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Early-Life Microbiome Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Product/Strain | Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probiotic Strains | Bifidobacterium longum BB536 | Prenatal supplementation studies | Reduces Crohn's disease severity; repairs mucus integrity [12] |

| Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG) | Early-life interventions | Modulates immune responses; affects gut bifidobacterial diversity [23] | |

| Bifidobacterium adolescentis & B. bifidum | Allergy prevention studies | Colonization patterns differ in allergic vs. non-allergic mothers [23] | |

| DNA Extraction Kits | CTAB/SDS method | Microbial community analysis | Provides high-quality DNA for low-biomass samples [24] |

| Sequencing Primers | 341F (CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG) & 806R (GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT) | 16S rRNA gene amplification (V3-V4 region) | Standardized for Illumina platforms; enables cross-study comparisons [24] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | BioBakery V3 pipeline | Metagenomic analysis | Harmonized computational processing for cross-study analyses [25] |

| FEAST algorithm | Microbial source tracking | Quantifies contributions of maternal microbial sources to neonatal gut [24] | |

| Cell Culture Media | Custom SCFA mixtures (acetate, propionate, butyrate) | Mechanistic in vitro studies | Physiological concentrations (μM to mM range); pH adjustment critical [28] |

Clinical Translation and Therapeutic Applications

Microbiome therapeutics represent a promising frontier for addressing early-life programming of long-term health outcomes. Current approaches include additive therapy (probiotics, fecal microbiota transplantation), subtractive therapy (antibiotics, bacteriophages), and modulatory therapy (prebiotics, microbial metabolites) [12]. Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) has demonstrated remarkable efficacy in recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection, with recovery rates exceeding 90% [12]. However, its application in other conditions like ulcerative colitis shows variable success, highlighting the need for optimized, targeted approaches.

Probiotic interventions during pregnancy and early infancy show potential for preventing specific conditions. Prenatal supplementation with Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG has been associated with reduced atopic dermatitis incidence, while combinations of multiple strains may enhance microbial stability in early colonization [23] [24]. The timing and duration of interventions appear critical, with transient effects observed in many studies and sustained changes requiring ongoing exposure or critical window targeting.

Emerging frontiers in microbiome therapeutics include engineered microbial consortia designed for specific functions and pharmacomicrobiomics – understanding how microbiome variations influence individual drug responses [10]. This integration of microbiome science with pharmacology holds particular promise for precision medicine approaches to pediatric and lifelong health.

Concluding Remarks and Future Directions

The critical window of early-life microbiome development represents both vulnerability and opportunity – a period when interventions may have disproportionate and lasting effects on health trajectories. The standardized protocols, analytical frameworks, and mechanistic insights provided in this Application Note establish a foundation for advancing research in microbiome clinical translation. Future directions should focus on validating multi-omics biomarkers across diverse populations, developing targeted therapeutic approaches for specific dysbiosis patterns, and establishing safety and efficacy guidelines for early-life microbiome interventions. As our understanding of microbial succession patterns and host-microbe interactions deepens, the potential grows for harnessing early-life programming to promote lifelong health and prevent disease.

Microbiome Modulators in the Clinic: From FMT to Next-Generation Biotherapeutics

Recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection (rCDI) represents a profound clinical challenge characterized by a destructive cycle of antibiotic treatments and subsequent recurrences that stem from persistent dysbiosis of the gut microbiome. The recent approval of two live biotherapeutic products—REBYOTA (fecal microbiota, live - jslm) and VOWST (fecal microbiota spores, live - brpk)—marks a transformative advancement in microbiome-based therapeutics, offering the first standardized, FDA-approved approaches to microbiome restoration [29]. These products represent the successful clinical translation of decades of research on the gut microbiome's crucial role in pathogen resistance, moving fecal microbiota transplantation from a largely unregulated procedure to a rigorously controlled pharmaceutical paradigm [30] [29]. This article provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for these groundbreaking therapies within the context of microbiome clinical translation, offering researchers and drug development professionals comprehensive guidance on their mechanisms, efficacy, and implementation.

Product Profiles and Comparative Analysis

REBYOTA: Single-Dose Rectal Microbiota Suspension

REBYOTA is a pre-packaged, single-dose 150 mL microbiota suspension for rectal administration consisting of a liquid mix of up to trillions of live microbes, including Bacteroides [31]. It is the first FDA-approved single-dose fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) indicated for the prevention of recurrence of CDI in individuals 18 years and older following antibiotic treatment for recurrent CDI [31] [30]. The product's standardized manufacturing process adheres to good manufacturing practices (GMP) and employs consistent, rigorous health screening of donors with each dose comprising a single donor's donation for ease of traceability [32].

VOWST: Orally Administered Fecal Microbiota Spores

VOWST represents the first orally administered fecal microbiota product approved by the FDA for prevention of rCDI recurrence in adults [33]. Its dosing regimen consists of four capsules taken once a day for three consecutive days [33]. VOWST is characterized as a purified bacterial spore suspension sourced from qualified donors and composed of Firmicutes spores, containing between 1×10^6 and 3×10^7 Firmicutes spore colony forming units [34]. The manufacturing process includes ethanol inactivation designed to help remove vegetative/pathogenic bacteria, fungi, parasites, and viruses, followed by filtration and centrifugation to remove solids and residual ethanol [34].

Table 1: Comparative Profile of FDA-Approved Microbiome Therapies for rCDI

| Parameter | REBYOTA | VOWST |

|---|---|---|

| FDA Approval Date | November 30, 2022 [30] | April 26, 2023 [33] [35] |

| Administration | Single-dose rectal suspension [31] | 4 capsules daily for 3 consecutive days (oral) [33] |

| Composition | Liquid mix of live microbes including Bacteroides and Firmicutes [32] | Purified Firmicutes spores [34] |

| Microbial Load | 15 billion to 7.5 trillion CFU per dose [32] | 1×10^6 to 3×10^7 Firmicutes spore CFU [34] |

| Key Clinical Trial | PUNCH CD3 Phase 3 [30] | ECOSPOR III Phase 3 [35] [36] |

| Treatment Success at 8 Weeks | 70.6% (vs 57.5% placebo) [30] | 88% (vs 60% placebo) [36] |

Table 2: Clinical Efficacy and Safety Profile Comparison

| Parameter | REBYOTA | VOWST |

|---|---|---|

| Sustained Response (6 months) | >90% (in responders) [30] | 79% recurrence-free [36] |

| Real-World Effectiveness | 75%-82.9% treatment success at 8 weeks [37] | 91% recurrence-free at 8 weeks (ECOSPOR IV) [36] |

| Most Common Adverse Events | Abdominal pain (8.9%), diarrhea (7.2%), bloating (3.9%), gas (3.3%), nausea (3.3%) [31] | Abdominal bloating (31.1%), fatigue (22.2%), constipation (14.4%), chills (11.1%), diarrhea (10.0%) [33] [35] |

| IBD Patient Efficacy | 78.9% treatment success at 8 weeks [38] | Limited data available |

| Mechanistic Insights | Increases beneficial Bacteroidia and Clostridia; decreases Gammaproteobacteria and Bacilli [31] | Engraftment of dose species greater than antibiotics alone through 8 weeks [34] |

Mechanism of Action and Engraftment Analysis

Microbiome Restoration Pathways

The therapeutic efficacy of both REBYOTA and VOWST centers on restoring a balanced gut microbiome to reestablish colonization resistance against C. difficile. In the case of REBYOTA, analysis of the Phase 3b CDI-SCOPE study demonstrated that microbiome composition and the Microbiome Health Index for post-antibiotic dysbiosis (MHI-A) shifted significantly toward the REBYOTA composition among responders [31]. Specifically, beneficial bacteria (Bacteroidia and Clostridia) increased in abundance, while disease-causing bacteria (Gammaproteobacteria and Bacilli) decreased following administration [31]. Importantly, MHI-A values increased from baseline to 6 months after treatment, indicating a sustained shift toward a healthier microbiome state [31].

For VOWST, which utilizes a purified spore approach, engraftment data from exploratory analysis in ECOSPOR III demonstrated that numbers of engrafting VOWST dose species were greater than antibiotics alone at week 1 and remained higher through week 8 [34]. The mechanism is thought to involve rapid facilitation of gut microbiome restoration and inhibition of spore germination that can perpetuate the cycle of C. difficile recurrence [34].

Diagram 1: Mechanism of Action Pathways for REBYOTA and VOWST

Engraftment Dynamics and Microbiome Metrics

Assessment of engraftment success requires specialized methodologies and biomarkers. For REBYOTA, investigators analyzed microbiome composition, diversity of bacterial populations, and the Microbiome Health Index for post-antibiotic dysbiosis (MHI-A) in participants with stool samples provided between baseline and 6 months [31]. The significant shift in MHI-A values toward healthier states provides a quantifiable metric for therapeutic response [31].

For VOWST, stool specimens for whole metagenomic sequencing were obtained at baseline and at weeks 1, 2, and 8 in the ECOSPOR III trial [34]. Of the 182 participants, 29 were excluded from analyses because of missing specimens or protocol deviations, highlighting the importance of rigorous sample collection protocols in engraftment studies [34]. The relationship between these engraftment data and efficacy or safety has not been definitively established, representing an area of ongoing investigation [34].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Clinical Trial Design for Microbiome Therapeutics

The pivotal clinical trials for REBYOTA and VOWST provide robust templates for future microbiome therapeutic development:

PUNCH CD3 Trial Protocol (REBYOTA):

- Design: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase 3 trial

- Participants: 262 patients with recurrent CDI; 177 received REBYOTA, 85 received placebo

- Primary Endpoint: Absence of CDI diarrhea for eight weeks following antibiotic treatment

- Statistical Analysis: Bayesian model estimating treatment success rate

- Results: 70.6% success rate for REBYOTA vs. 57.5% for placebo (99.1% posterior probability of superiority)

- Long-term Follow-up: >90% of participants maintaining remission through 6 months post-treatment [30]

ECOSPOR III Trial Protocol (VOWST):

- Design: Multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial across 50+ sites in U.S. and Canada

- Participants: Adults with recurrent CDI

- Primary Endpoint: CDI recurrence at eight weeks post-treatment

- Results: 88% of VOWST group recurrence-free at 8 weeks vs. 60% for placebo; 79% recurrence-free at 6 months vs. 53% for placebo [36]

- Open-label Extension: ECOSPOR IV study showed 91% recurrence-free at 8 weeks and 86% at 24 weeks [36]

Microbiome Sampling and Analysis Protocol

Sample Collection:

- Collect stool specimens at baseline (pre-treatment) and at predetermined intervals post-treatment (weeks 1, 2, 8, and 24)

- Immediately freeze samples at -80°C to preserve microbial viability and genetic integrity

- Document and track any protocol deviations or missing specimens that may affect analysis

DNA Extraction and Sequencing:

- Perform standardized DNA extraction using commercially available kits designed for microbial diversity studies

- Conduct whole metagenomic sequencing using Illumina or comparable platforms

- Include appropriate controls for contamination and sequencing depth

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Process raw sequencing data through quality control (FastQC), adapter trimming, and host DNA depletion

- Perform taxonomic profiling using reference databases (Greengenes, SILVA)

- Calculate diversity metrics (alpha and beta diversity) and differential abundance testing

- For VOWST specifically, track engraftment of dose species compared to baseline [34]

- For REBYOTA, analyze Microbiome Health Index for post-antibiotic dysbiosis (MHI-A) [31]

Diagram 2: Clinical Trial Workflow for Microbiome Therapies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Microbiome Therapeutic Development

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Specifications/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| Stool Collection Kits | Standardized sample acquisition for microbiome analysis | Includes DNA/RNA stabilizing buffers, temperature control during transport |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Microbial DNA isolation for metagenomic sequencing | MoBio PowerSoil Kit or equivalent; optimized for Gram-positive bacteria |

| Whole Metagenomic Sequencing | Comprehensive taxonomic and functional profiling | Illumina NovaSeq, PacBio, or Oxford Nanopore platforms |

| Bioinformatic Pipelines | Analysis of microbial community data | QIIME 2, mothur, or custom workflows for taxonomic assignment |

| Cdiff32 Instrument | Health-related quality of life assessment in CDI patients | Validated survey instrument capturing physical, mental, social functioning [37] |

| Anaerobic Chambers | Cultivation of oxygen-sensitive gut microorganisms | Coy Laboratory Type B Vinyl Anaerobic Chambers or equivalent |

| Gnotobiotic Mouse Models | In vivo assessment of microbiome engraftment and function | Germ-free facilities for human microbiota transplantation studies |

| Cell-Based Assays | Assessment of bacterial sporulation, germination, and cytotoxicity | Caco-2 cell lines for epithelial barrier function; Vero cells for toxin testing |

Future Directions and Research Applications

The development of REBYOTA and VOWST represents just the beginning of microbiome-based therapeutics. Ongoing clinical trials continue to explore the efficacy of these products in special populations, including patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). A recent subgroup analysis of PUNCH CD3-OLS demonstrated that REBYOTA was safe and efficacious in patients with IBD, showing a 78.9% treatment success rate at 8 weeks and 91.1% sustained clinical response at 6 months, similar to rates in non-IBD participants [38]. This is particularly significant as IBD is a common risk factor for rCDI, yet patients with IBD are often excluded from prospective trials [38].

Future research directions include:

- Optimizing Administration Protocols: Investigating extended antibiotic washout periods beyond the standard 24-72 hours [31]

- Novel Formulations: Developing next-generation products with enhanced stability and administration profiles

- Mechanistic Studies: Delineating precise microbial shifts and metabolic changes associated with successful treatment

- Combination Therapies: Exploring microbiota restoration in conjunction with immunomodulatory agents

- Expanded Indications: Investigating applications in other gastrointestinal disorders, metabolic conditions, and neurological diseases [30] [35]

The standardized manufacturing processes, rigorous donor screening protocols, and robust clinical evidence supporting REBYOTA and VOWST establish a benchmark for future microbiome-based therapeutics, paving the way for expanded applications in gastrointestinal and extraintestinal disorders linked to dysbiosis [29].

The field of Live Biotherapeutic Products (LBPs) has progressed from a scientific concept to a validated therapeutic modality, with the global human microbiome market projected to exceed USD 5.1 billion by 2030 [39]. Following the landmark approvals of Rebyota and Vowst for recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection (rCDI), the pipeline has expanded dramatically, now encompassing over 240 candidates in development across more than 100 companies [39]. This article provides a detailed overview of the current LBP pipeline and experimental frameworks essential for advancing these next-generation therapeutics.

LBP Pipeline and Therapeutic Landscape

The LBP pipeline reflects a strategic diversification from initial infectious disease applications into complex chronic conditions, including oncology, metabolic, and neurodegenerative diseases [39]. The table below summarizes selected prominent LBP candidates in development.

Table 1: Selected Live Biotherapeutic Products (LBPs) in Clinical Development

| Company / Product | Indication(s) | Modality & Mechanism | Development Stage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seres Therapeutics – Vowst (SER-109) [39] | rCDI; exploring ulcerative colitis | Oral LBP; purified Firmicutes spores that recolonize the gut and restore bile acid metabolism | Approved (FDA) |

| Ferring Pharma/Rebiotix – Rebyota (RBX2660) [39] | rCDI | Rectally administered microbiota suspension; restores broad microbial diversity | Approved (FDA) |

| Vedanta Biosciences – VE303 [40] [39] | rCDI | Defined eight-strain bacterial consortium; promotes colonization resistance | Phase III |

| Vedanta Biosciences – VE202 [39] | Ulcerative Colitis (IBD) | Eight-strain consortium designed to induce regulatory T-cell responses | Phase II |

| 4D Pharma – MRx0518 [39] | Oncology (solid tumors) | Single-strain Bifidobacterium longum engineered to activate innate and adaptive immunity | Phase I/II |

| MaaT Pharma – MaaT013 [39] | Graft-versus-host disease | Pooled, high-richness microbiome ecosystem therapy to restore immune homeostasis | Phase III |

| Synlogic – SYNB1934 [39] | Phenylketonuria (PKU) | Engineered E. coli Nissle expressing phenylalanine ammonia lyase to metabolize phenylalanine | Phase II |

| Akkermansia Therapeutics – Ak02tm [39] | Metabolic disorders | Pasteurized Akkermansia muciniphila for improving insulin sensitivity | Phase I/II |

| Finch Therapeutics – CP101 [40] [39] | rCDI; exploring IBD | Full-spectrum microbiota consortium delivered via oral capsules | Phase II/III |

| BiomX – BX003 [39] | Atopic dermatitis & acne | Topical bacteriophage cocktail targeting Cutibacterium species | Phase II |

The distribution of candidates across development stages indicates a sector still in its early clinical translation. An estimated 60% of microbiome therapeutics are in preclinical stages, while Phase I, Phase II, and Phase III trials represent approximately 20%, 15%, and less than 5% of the pipeline, respectively [39]. This distribution underscores the significant growth and future attrition expected as programs advance.

Key Therapeutic Areas and Modalities

- Gastrointestinal Disorders: While rCDI remains a cornerstone, development has actively expanded into inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) [39] [41]. For complex diseases, the therapeutic rationale moves beyond simple ecosystem restoration to precise immunomodulation [42].

- Oncology: LBPs are being developed as adjuvants to enhance response to checkpoint inhibitors and manage complications like graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) [39] [42].

- Metabolic and Neurodegenerative Diseases: Strains like Akkermansia muciniphila are being evaluated for metabolic benefits [39], while the microbiota-gut-brain axis is a target for conditions like Parkinson's disease [40] [11].

- Product Architectures: Three distinct LBP architectures have emerged to address different clinical needs [42]:

- Whole-Community Products: Designed to replicate the ecosystem restoration of FMT (e.g., Rebyota).

- Partial-Community or Enriched Products: Balance diversity with manufacturing control (e.g., Vowst, MaaT013).

- Defined-Strain Products: Target specific mechanisms of action using rationally selected single strains or consortia (e.g., VE303, MRx0518).

Experimental Protocols for LBP Development

Advancing LBPs requires specialized protocols that address the unique challenges of working with live microorganisms. The following sections detail key methodologies for strain selection and efficacy assessment.

Protocol: Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GEM)-Guided Strain Screening

Application Note: This in silico protocol uses GEMs to rationally shortlist LBP candidate strains from public databases like AGORA2 (which contains 7,302 curated strain-level GEMs of gut microbes) based on predicted therapeutic functions [40]. It efficiently narrows down candidates for experimental validation.

Table 2: Key Reagents for GEM-Guided Screening

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| AGORA2 Model Resource [40] | A library of curated, strain-level genome-scale metabolic models for gut microbes; serves as the starting database for in silico screening. |

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) [40] | A computational method used to simulate metabolic flux and predict growth rates, nutrient uptake, and metabolite secretion under defined constraints. |

| Therapeutic Metabolite List | A user-defined list of disease-relevant beneficial (e.g., butyrate) or detrimental metabolites used to query model outputs. |

| Pairwise Interaction Simulation | In silico method to predict mutualistic, competitive, or neutral interactions between a candidate LBP strain and key resident gut microbes. |

Procedure:

- Define Therapeutic Objective: Based on disease pathophysiology (e.g., butyrate deficiency in IBD), define the desired metabolic output or function for the LBP [40].

- Retrieve and Constrain GEMs: Select relevant microbial GEMs from AGORA2 or reconstruct new ones. Apply constraints to simulate the disease-relevant gut environment (e.g., nutrient availability) [40].

- In Silico Phenotype Screening:

- Simulate growth and metabolic secretion profiles for each model.

- Screen for strains with a high production potential for beneficial postbiotics (e.g., short-chain fatty acids) and a low potential for detrimental metabolites [40].

- Evaluate Microbial Interactions:

- Perform pairwise in silico growth simulations between candidate strains and representative resident or pathogenic microbes.

- Identify candidates that exhibit antagonism against specific pathogens (e.g., Escherichia coli) or synergistic relationships with beneficial commensals [40].

- Generate Candidate Shortlist: Rank strains based on a combined score of production potential and beneficial interaction profile. The output is a prioritized list for in vitro and in vivo testing.

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and decision points in this screening protocol.

Protocol: Assessing LBP Efficacy via the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis

Application Note: This protocol outlines a mechanistic in vivo workflow to evaluate the efficacy of an LBP for neurodegenerative diseases, using the microbiota-gut-brain axis as a framework [11]. It focuses on measuring glial cell responses and key metabolites.

Procedure:

- Animal Model and LBP Administration:

- Use a relevant transgenic or chemically-induced mouse model of neurodegeneration (e.g., 5xFAD for Alzheimer's disease) [11].

- Randomize animals into LBP treatment and control groups. Administer the LBP (e.g., a defined bacterial consortium) via oral gavage over a predefined treatment period.

- Behavioral and Cognitive Testing: Conduct behavioral assays relevant to the disease model (e.g., maze tests for memory and learning) at baseline and post-treatment [11].

- Sample Collection and Tissue Processing:

- Collect fresh fecal samples for microbiome (16S rRNA sequencing) and metabolome (LC-MS) analysis.

- Following perfusion, dissect and harvest brain regions of interest (e.g., hippocampus, cortex). Process tissue for immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry, or RNA sequencing.

- Immunohistochemical Analysis of Glial Cells:

- Stain brain sections with antibodies against Iba1 (for microglia) and GFAP (for astrocytes).

- Quantify glial activation states based on morphological changes: ramified (resting) vs. amoeboid (activated) microglia, and hypertrophy of astrocytes [11].

- Metabolomic and Immunological Profiling:

- Quantify levels of gut microbiota-derived metabolites (e.g., short-chain fatty acids, bile acids) in serum and brain tissue using targeted mass spectrometry [11].

- Measure plasma levels of inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1β, TNF-α) and gut hormones (e.g., GLP-1) via multiplex immunoassays.

- Correlative Data Integration: Statistically correlate changes in the gut microbiome composition, key metabolite levels, glial activation status, and cognitive performance scores to infer mechanism of action.

The diagram below maps the key pathways of the microbiota-gut-brain axis that this protocol investigates.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

Successful LBP development relies on specialized reagents and tools to address unique challenges in manufacturing and analysis.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for LBP Development

| Research Reagent / Solution | Function / Application in LBP Development |

|---|---|

| Chemically Defined Media | Supports consistent, scalable GMP fermentation; requires optimization to eliminate undefined/animal-derived components for robust anaerobic growth [40] [42]. |

| Cryoprotectants & Lyophilization Formulations | Protects strain viability during freeze-drying and long-term storage; formulation is highly strain-specific and requires parameter optimization [42]. |

| Anaerobic Chamber & GMP Fermenters | Essential for cultivating oxygen-sensitive, obligate anaerobes; specialized equipment maintains strict anaerobic conditions from culture to final product fill [43]. |

| Strain-Specific Phenotypic Assays | Functional tests (e.g., bile acid conversion, bacteriocin production) to confirm strain-level potency and mechanism of action beyond genetic identification [42]. |

| GMP-Grade Caspules with Oxygen Barrier | Protects viability of lyophilized live products for oral delivery; requires low moisture content and excellent oxygen barrier properties [43]. |

| Pan-Microbiome Profiling Tools (16S rRNA, Shotgun Metagenomics) | For assessing in vivo engraftment, batch-to-batch quality control, and patient stratification based on baseline microbiome composition [39]. |

| Pathogen Screening Assays | Comprehensive, multi-target PCR and NGS-based tests for donor and product safety screening to exclude known pathogens and virulence factors [42]. |

| Immunomodulation Readout Systems | In vitro cell-based assays (e.g., PBMC or dendritic cell co-culture) to quantify strain-specific immunomodulatory effects (e.g., Treg induction) [42]. |

The LBP pipeline, now exceeding 180 drugs in development, represents a fundamental expansion of the pharmaceutical landscape. The transition from whole-community products to rationally designed, defined-strain consortia and engineered microbes underscores a maturation of the field. Success in this complex modality hinges on the integrated application of robust experimental protocols—from in silico strain selection using GEMs to mechanistic efficacy studies via the gut-brain axis—along with a deep understanding of the associated manufacturing and regulatory challenges. As the pipeline continues to evolve, these detailed application notes and protocols provide a critical foundation for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to translate microbiome science into novel therapeutics.

The translation of microbiome-based therapies from bench to bedside is accelerating, with all three modalities showing promising results in clinical and preclinical settings for a range of conditions. The tables below summarize key quantitative findings and developmental status.

Table 1: Clinical and Preclinical Outcomes of Novel Therapeutic Modalities

| Therapeutic Modality | Target Condition / Model | Key Efficacy Findings | Reference / Trial Stage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personalized Inhaled Phage Therapy | Cystic Fibrosis (CF) with MDR/PDR Pseudomonas aeruginosa [44] | - Sputum P. aeruginosa decreased by a median of 104 CFU mL-1 post-therapy [44]- Mean improvement of 8% in ppFEV1 (lung function) [44] | Nature Medicine 2025; Compassionate Use [44] |

| Engineered E. coli Nissle 1917 | Phenylketonuria (PKU) [45] | Engineered to produce PAL and LAAD enzymes for degradation of excess phenylalanine in the gut [45] | Preclinical / Engineering Validation [45] |

| Engineered Lactococcus lactis | Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) - Colitis Model [45] | Secretion of human interleukin-10 leading to successful alleviation of colitis in murine models [45] | Preclinical (Murine Model) [45] |

| Defined Bacterial Consortium | Necrotizing Enterocolitis (NEC) in Preterm Infants [46] | 27% reduction in all-cause mortality in a phase 3 trial of 2,158 premature infants [47] | Phase 3 Clinical Trial (IBP-9414) [47] |

| Phage-Antibiotic Synergy (PAS) | Diverse Infections (Pulmonary, Soft Tissue, etc.) [48] | Combination therapy showed ~70% superior eradication rates compared to phage monotherapy [48] | Multicenter Cohort Study [48] |

Table 2: Market Analysis and Developmental Status of Microbiome Therapeutics

| Parameter | Phage Therapy | Engineered Strains | Defined Consortia |

|---|---|---|---|

| Market Valuation & Growth (2025) | $38 million; 17.6% CAGR projected [49] | N/A (Primarily preclinical/early clinical) | N/A (Varies by product and stage) |