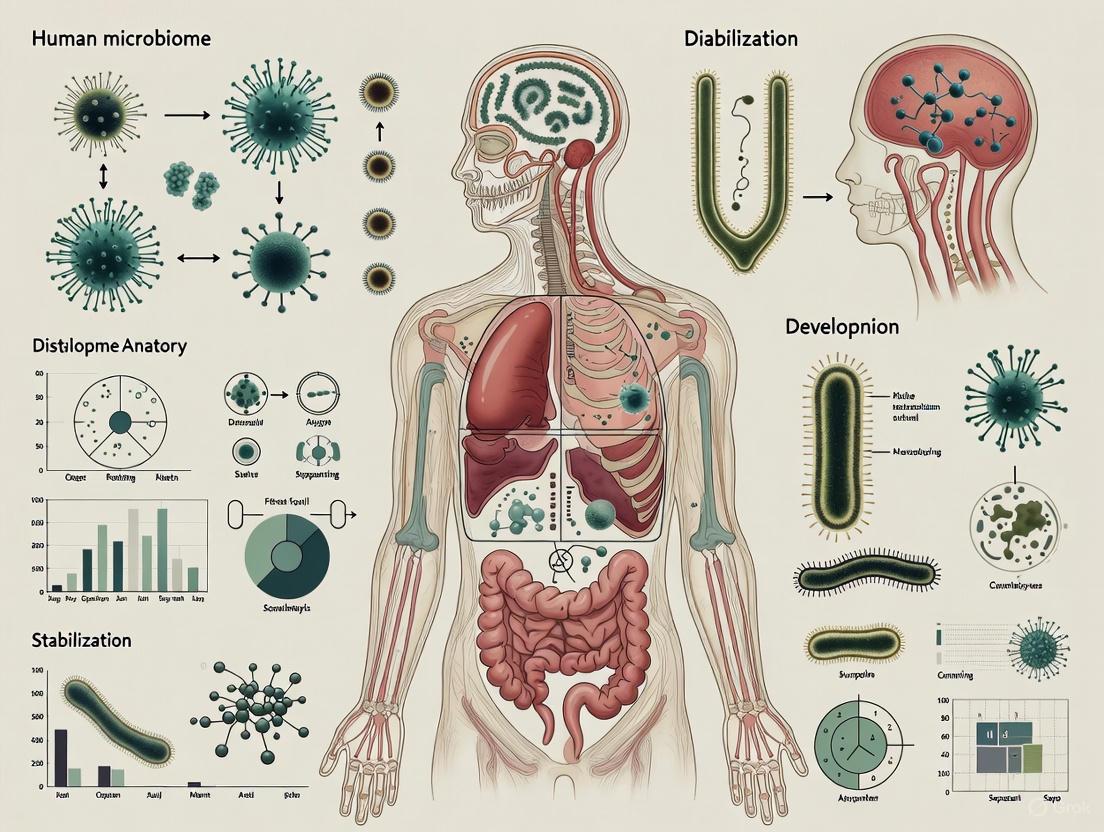

Human Microbiome Anatomy and Development: From Foundational Distribution to Therapeutic Stabilization

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the human microbiome for researchers and drug development professionals.

Human Microbiome Anatomy and Development: From Foundational Distribution to Therapeutic Stabilization

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the human microbiome for researchers and drug development professionals. It synthesizes current knowledge on the anatomical distribution and developmental trajectory of microbial communities from birth to adulthood. The scope extends from foundational ecological principles and core microbiome concepts to advanced methodological applications in live biotherapeutic products (LBPs) and fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT). It further addresses challenges in managing dysbiosis, optimizing microbial resilience, and validates approaches through comparative analysis of the clinical pipeline and AI-driven predictive models. This resource is designed to bridge foundational microbiome science with translational clinical applications.

Mapping the Human Microbiome: Anatomical Distribution, Core Concepts, and Developmental Trajectory

The human body functions as a complex, heterogeneous landscape for microbial colonization. Understanding the spatial organization of the microbiome—specifically the variations in microbial density and diversity across different anatomical sites—is fundamental to a broader thesis on human microbiome distribution, anatomy, development, and stabilization research. This spatial patterning is not random; it reflects profound evolutionary adaptations, anatomical constraints, and physiological functions [1]. The precise mapping of these gradients provides a critical baseline for health and a reference for identifying dysbiosis in disease states. For researchers and drug development professionals, this knowledge is pivotal for designing targeted therapies, from site-specific probiotic delivery to novel antibiotics and microbiome-based diagnostics. Advances in spatial omics technologies and large-scale mapping projects are now enabling an unprecedented, high-resolution view of this microbial topography, moving beyond bulk compositional analysis to reveal the intricate, location-specific relationships between microbes and their human host [2].

Quantitative Atlas of Microbial Distribution

The distribution of microorganisms throughout the human body is highly uneven, governed by local environmental conditions such as pH, oxygen levels, moisture, and nutrient availability. The quantitative density of bacterial presence across major anatomical niches has been systematically characterized, providing a foundational metric for spatial organization.

Table 1: Microbial Density Gradients Across Major Anatomical Sites

| Anatomical Site | Relative Bacterial Density (%) | Predominant Microbial Phyla | Key Spatial Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal Tract | 29% | Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes | Highest density; gradient from low density in stomach/duodenum to highest in colon [1] |

| Oral Cavity | 26% | Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria | High diversity; site-specific niches (tongue, plaque, gums) [1] |

| Skin | 21% | Actinobacteria, Firmicutes, Proteobacteria | Medium density; varies by skin region (sebaceous, moist, dry) [1] |

| Respiratory Tract | 14% | Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria | Density gradient: higher in upper tract, lower in lower tract [1] |

| Urogenital Tract | 9% | Firmicutes (e.g., Lactobacillus), Actinobacteria | Low density; composition sensitive to physiological changes [1] |

Beyond density, the concept of diversity gradients is equally critical. For instance, the gastrointestinal tract exhibits not only a density gradient but also a succession of microbial communities from the stomach to the colon, each adapted to the distinct physicochemical conditions of these sub-niches [1]. Similarly, the respiratory tract shows a decreasing gradient in both microbial density and diversity from the nasal passages to the alveoli, a feature essential for maintaining sterile conditions in the deep lungs [1].

Methodological Foundations for Spatial Microbiome Analysis

Elucidating the spatial architecture of the microbiome requires a suite of advanced technologies. The following experimental workflows represent cutting-edge methodologies for mapping microbiome density and diversity with high resolution.

High-Resolution Multimodal Spatial Atlas Construction

The Spatial Atlas of Human Anatomy (SAHA) project exemplifies a robust, multimodal framework for generating a subcellular-resolution reference of human tissues, integrating spatial transcriptomics, proteomics, and histological data [2].

Table 2: Key Experimental Protocols from the SAHA Framework

| Protocol Step | Detailed Methodology | Primary Objective |

|---|---|---|

| Tissue Procurement & Processing | Standardized collection from over 100 donors; rigorous quality control; fixation and embedding to preserve spatial context and biomolecule integrity [2]. | Minimize batch effects and cross-platform variability for robust data integration. |

| Multimodal Spatial Profiling | Sequential or parallel imaging using:• CosMx SMI: 1000-plex RNA, 67-plex protein.• 10x Xenium: High-throughput transcriptomics.• RNAscope: For RNA integrity assessment and validation.• GeoMx DSP: Region-specific protein and RNA profiling [2]. | Generate complementary, high-plex molecular data at subcellular (50 nm) resolution. |

| Cell Detection & Annotation | Automated recognition algorithms followed by manual curation; cell type annotation using canonical marker genes; validation via immunohistochemistry [2]. | Precisely identify and label over 50 distinct cell types (epithelial, immune, stromal, neuronal). |

| Spatial Registration & Data Integration | Registration of individual cells to a standardized brain coordinate framework (e.g., Allen CCFv3); use of UMAP for visualization; cell-cell adjacency mapping and ligand-receptor interaction analysis [2]. | Enable cross-organ and cross-donor comparisons; identify cellular neighborhoods and interaction networks. |

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for constructing a high-resolution spatial atlas, integrating multiple profiling platforms to map cellular and microbial neighborhoods.

Strain-Level Metagenomic Analysis for Global Diversity

To understand global genetic diversity and transmission patterns, large-scale metagenomic sequencing and strain-level phylogenetic analysis are employed. This approach moves beyond taxonomic classification to assess intraspecies genetic variability, which is crucial for linking specific microbial lineages to host phenotypes and geographical stratification [3].

Detailed Protocol Workflow:

- Sample Collection & Metagenomic Sequencing: 32,152 metagenomes from 94 global studies were collected and sequenced using shotgun metagenomics [3].

- Strain-Level Phylogenetic Reconstruction: Species-specific phylogenies were reconstructed for 583 microbial species from the metagenomic data. This allows for the tracking of specific microbial strains [3].

- Phenotype-Genotype Integration: The reconstructed microbial clades are linked to 241 host phenotypes, including anthropometric factors, biochemical measurements, and diseases [3].

- Geographic and Transmission Analysis: Strain geographic stratification is analyzed in relation to the species' horizontal transmissibility, providing insights into microbial dispersal and acquisition [3].

Conceptual Models of Microbiome Organization and Stability

Spatial organization has profound functional implications, influencing ecosystem stability and host-microbe interactions. The "Two Competing Guilds" (TCG) model, identified through systems biology and network analysis, provides a functional framework for understanding this organization.

Figure 2: The Two Competing Guilds (TCG) model depicts the core microbiome as a balance between health-promoting and disease-driving forces.

This model posits that the core gut microbiome is structured around two functionally antagonistic groups: the Foundation Guild (FG), dominated by Short-Chain Fatty Acid (SCFA)-producing bacteria, and the Pathobiont Guild (PG), enriched with opportunistic pathogens and pro-inflammatory microbes [4]. These guilds represent opposing functional forces, and their spatial and ecological balance directly influences host health.

The relational stability between these guilds is more significant than the mere presence of individual taxa. Network analysis of 38 microbiome datasets revealed that TCG members, though constituting less than 10% of total microbial members, form the ecosystem's backbone, accounting for 85% of all ecological interactions [4]. The FG members, such as Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Roseburia spp., produce SCFAs that inhibit PG microbes, enhance gut barrier integrity, and mitigate inflammation [4]. This stable, competitive relationship is a key spatial-functional determinant of microbiome health.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Platforms

To replicate and advance the research outlined in this whitepaper, scientists require access to a specific set of high-end reagents, technologies, and computational tools.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Spatial Microbiome Analysis

| Category / Item | Specific Function / Example | Application in Spatial Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Transcriptomics Platforms | CosMx SMI, 10x Xenium, GeoMx DSP [2] | Subcellular mapping of host and microbial RNA in intact tissue sections. |

| Multiplex Proteomics Panels | CosMx protein panel (67-plex) [2] | Simultaneous detection of dozens of proteins to define cell states and immune responses. |

| In Situ Hybridization Reagents | RNAscope assays [2] | Validation of RNA integrity and precise localization of specific microbial or host transcripts. |

| Bioinformatic Analysis Suites | Algorithms for cell detection, spatial registration (e.g., to Allen CCFv3), and network analysis [2] [3] | Automated cell typing, 3D reconstruction, and quantification of cellular neighborhoods. |

| Strain-Tracking Metagenomics Tools | Computational pipelines for strain-level phylogenetic reconstruction from metagenomes [3] | Linking global genetic diversity of microbes to host phenotypes and geographic origins. |

| Gnotobiotic Animal Models | Germ-free mice [1] [5] | Establishing causality by studying host physiology in the absence of microbes and after targeted colonization. |

| o-Cresol-d7 | o-Cresol-d7 Isotopic Standard | High-purity o-Cresol-d7 isotopic standard for MS, NMR, and environmental tracer studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| L-Methionine-34S | L-Methionine-34S, MF:C5H11NO2S, MW:151.11 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The systematic mapping of density and diversity gradients across major anatomical sites provides an indispensable spatial framework for human microbiome research. The integration of multimodal spatial omics, as demonstrated by the SAHA atlas, with large-scale, strain-resolved metagenomics represents the frontier of this field. This synergy allows researchers to move from correlative observations to mechanistic understandings of how specific microbial communities, positioned in precise anatomical niches, influence human physiology and disease. For drug development, these insights are paving the way for next-generation therapies. This includes the design of precision delivery systems that target specific gut regions [6], the development of rationally defined consortia of microbes (synthetic biotics) [7], and the use of phage therapies targeting pathogens within complex biofilms [7]. As these spatial technologies become more accessible and computational models more sophisticated, the future of microbiome research lies in comprehensively charting this intricate landscape to develop novel, spatially informed diagnostics and therapeutics.

The long-standing doctrine of human sterility at internal sites is undergoing a profound reassessment. Traditional human anatomy has taught that organs such as the brain, vascular system, and placenta exist in sterile isolation from the microbial world. However, emerging evidence from advanced sequencing technologies and carefully controlled studies challenges this paradigm, suggesting that these sites may host resident microbial communities under certain conditions [1]. This whitepaper examines the compelling evidence and methodological considerations surrounding microbiome presence in traditionally sterile human sites, framed within the broader context of human microbiome distribution, anatomy, development, and stabilization research. Understanding these microbial communities requires a systematic framework that considers anatomical distribution, physiological functions, and the complex interplay between microbial and human genomes [1]. The implications for disease pathogenesis, diagnostic approaches, and therapeutic development are substantial, potentially reshaping fundamental concepts in human physiology and pathology.

Evidence for Microbiome Presence in Traditionally Sterile Sites

Vascular System Microbiota

The human vascular system, long presumed to be sterile, now shows evidence of hosting microbial communities in both health and disease states. Atherosclerotic vessels demonstrate a non-sterile environment containing bacteria and viruses, with arterial atherosclerosis sequencing providing compelling evidence [1]. A rigorous study employing strict exclusion criteria, aseptic sampling, repeated measures, and negative controls to eliminate potential contamination analyzed femoral arteries from brain-dead donors, predominantly those with hemorrhagic or ischemic strokes [1]. The research identified Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, and Actinobacteria as the predominant phyla, with Staphylococcus, Pseudomonas, Corynebacterium, Bacillus, Acinetobacter, and Propionibacterium representing prevalent genera [1]. Interestingly, the study also observed a notable correlation between blood type and microbiota diversity, suggesting potential host genetic factors influencing vascular microbial colonization [1]. However, limitations including small sample size (14 participants) and restricted age range (40-60 years) necessitate cautious interpretation and further validation.

Despite these findings, the sterility of blood in healthy individuals remains supported by substantial evidence. An analysis of 9,770 samples from healthy individuals in the Human Microbiome Project revealed the absence of similar microbial communities in the bloodstream, with 82% of the sampled population exhibiting no microbial sequences [1]. This dichotomy suggests that vascular microbiota may represent a disease-associated phenomenon rather than a baseline physiological state, though temporal dynamics and methodological limitations leave this question open for further investigation.

Ocular Surface and Brain Microbiota

The human ocular surface, despite constant exposure to the environment and protective mechanisms, hosts a diverse microbiome that includes Pseudomonas, Bradyrhizobium, Propionibacterium, Acinetobacter, and Corynebacterium as the most abundant genera [1]. This community exists despite the antimicrobial properties of tears and frequent blinking, suggesting sophisticated adaptation mechanisms.

Perhaps most controversially, the brain—long considered the archetypal sterile organ due to the protective blood-brain barrier—has shown potential evidence of microbial presence. Surprising findings from microscopic examination of multiple brain regions in post-mortem healthy individuals, presented at a neuroscience conference, have suggested the existence of microbiota in the brain [1]. However, the scientific community awaits confirmation through rigorous animal models and independent human validation studies [1]. The potential mechanisms for microbial entry into the brain, including transcellular migration, Trojan horse mechanisms, or peripheral nerve pathways, remain speculative without stronger evidence.

Other Potentially Non-Sterile Sites

Other anatomical sites are similarly challenging traditional sterility assumptions:

- Gallbladder: Though sampling difficulties exist, studies have confirmed the presence of microbial communities in the gallbladder, potentially through retrograde entry of gastrointestinal microbiota [1].

- Mammary Tissue: Women aged 18-90 show a diverse range of bacteria, predominantly Proteobacteria, in mammary tissue [1].

- In Utero Environment: The question of whether a normal fetus is colonized by microbes prenatally ("in utero colonization" hypothesis) remains highly controversial, challenging the established "sterile womb" paradigm [1]. A recent comprehensive discussion suggests that detected microbes may represent contamination rather than true colonization, emphasizing the lack of reliable evidence for consistent microbial presence [1].

Table 1: Evidence for Microbiome Presence in Traditionally Sterile Sites

| Anatomical Site | Key Microbial Findings | Strength of Evidence | Controversies/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vascular System | Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Actinobacteria; Staphylococcus, Pseudomonas, Corynebacterium | Moderate in disease states; Limited in health | Potential contamination; Small sample sizes; Blood largely sterile in healthy individuals |

| Ocular Surface | Pseudomonas, Bradyrhizobium, Propionibacterium, Acinetobacter, Corynebacterium | Established | Differentiation between resident vs. transient communities |

| Brain | Potential presence based on post-mortem examination | Preliminary | Requires animal model confirmation; Independent validation needed |

| Gallbladder | Microbial communities present | Moderate | Retrograde GI migration suspected; Sampling difficulties |

| Mammary Tissue | Proteobacteria predominant | Established | Age range 18-90 studied |

| In Utero Environment | Potential microbial presence | Highly controversial | Likely contamination; No reliable evidence of consistent colonization |

Methodological Approaches and Technical Considerations

Sequencing Technologies and Their Applications

The investigation of microbiomes in low-biomass environments like traditionally sterile sites requires sophisticated sequencing approaches, each with distinct advantages and limitations:

DNA Metabarcoding (Amplicon Sequencing): This approach characterizes samples using reads obtained through selective amplification of marker genes like the 16S rRNA gene for prokaryotes or ITS regions for fungi [8]. While cost-effective and suitable for detecting rare taxa with approximately 100,000 reads per sample, it faces three main limitations: (1) Restricted taxonomic resolution due to conservation of marker genes, (2) Inherent limitations in functional profiling, and (3) Vulnerability to PCR amplification errors and biases including undersampling, contamination, storage conditions, and polymerase errors [8]. Tools like PICRUSt2 and Tax4Fun2 attempt functional prediction from taxonomic profiles but with limited accuracy and resolution [8].

Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing: This method involves isolation of DNA from samples followed by deep sequencing without target-specific amplification [8]. Shotgun metagenomics enables high-resolution taxonomic profiling from phylum to strain level and allows study of the functional potential of microbial communities through gene identification and pathway analysis [8]. However, it requires greater sequencing depth, is more costly, and generates data that is typically more sparse than 16S rRNA data [9].

Multi-Omics Integration: Advanced approaches including metatranscriptomics, metaproteomics, and metabolomics provide complementary insights into microbial community function beyond compositional assessment [8]. Metatranscriptomics measures mRNA levels to reveal actively expressed functions, while metaproteomics identifies and quantifies proteins actually produced by the community [10]. Metabolomics profiles the small molecule metabolites produced, offering the most direct readout of microbial functional activities [8].

Special Considerations for Low-Biomass Sites

Research on microbiomes in traditionally sterile sites presents unique methodological challenges:

Contamination Control: The low microbial biomass in these environments makes them exceptionally vulnerable to contamination during sampling, processing, or sequencing. Strategies include implementation of strict exclusion criteria, aseptic sampling techniques, repeated measures, negative controls, and careful documentation of potential confounding factors [1].

Metadata Collection: Comprehensive and standardized metadata is crucial for interpreting results and comparing datasets across studies [8]. This includes detailed information about sample collection, processing, sequencing parameters, and host characteristics. Incomplete metadata hinders the ability to perform robust data stratifications and account for confounding factors [8].

Computational and Statistical Methods: Microbiome data analysis must account for characteristics including zero inflation, overdispersion, high dimensionality, compositionality, and sample heterogeneity [9]. Statistical methods for differential abundance analysis include edgeR, metagenomeSeq, DESeq2, ANCOM, ZIBSeq, ZIGDM, and corncob, each with different normalization approaches and underlying models [9].

Research Workflow for Sterile Site Microbiome Studies

Analytical Framework and Technical Challenges

Statistical Considerations for Microbiome Data Analysis

Microbiome data derived from traditionally sterile sites presents unique statistical challenges that require specialized analytical approaches:

Compositional Data Analysis: microbiome sequencing data is compositional, meaning that counts are relative rather than absolute due to variable sequencing depth across samples [9]. This compositionality necessitates special statistical methods that account for the constrained nature of the data, with false positives potentially arising from analyzing relative abundances as if they were absolute measurements [9].

Zero Inflation and Overdispersion: Microbiome datasets typically contain a high proportion of zeros (up to 90% in some cases), with both true absences and false zeros due to technical limitations [9]. These data also exhibit overdispersion, where variance exceeds the mean, violating assumptions of standard statistical models. Methods like zero-inflated models (ZIBSeq, ZIGDM) specifically address these characteristics [9].

Batch Effects and Normalization: Technical variability arising from different DNA extraction methods, sequencing runs, or laboratory personnel can introduce batch effects that confound biological signals [9]. Normalization approaches including Total Sum Scaling (TSS), Cumulative Sum Scaling (CSS), Relative Log Expression (RLE), and Trimmed Mean of M-values (TMM) help account for variable sequencing depth, while methods like ComBat, removeBatchEffect, and surrogate variable analysis (SVA) address batch effects specifically [9].

Table 2: Key Analytical Methods for Sterile Site Microbiome Data

| Analytical Challenge | Statistical Methods | Key Features | Applicability to Sterile Sites |

|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Abundance Analysis | edgeR, DESeq2, metagenomeSeq, ANCOM, corncob | Accounts for compositionality, zero inflation, overdispersion | High (essential for low-biomass comparisons) |

| Batch Effect Correction | ComBat, removeBatchEffect, SVA, RUV | Removes technical variability from different processing batches | Critical (due to heightened contamination concerns) |

| Normalization | TSS, CSS, TMM, RLE | Adjusts for variable sequencing depth | Essential (particularly for cross-study comparisons) |

| Functional Prediction | PICRUSt2, Tax4Fun2 | Infers functional potential from taxonomic data | Moderate (limited by reference database completeness) |

| Network Analysis | SparCC, SPIEC-EASI, MInt | Infers microbial association networks | Emerging (requires sufficient sample size) |

Contamination Identification and Control

For low-biomass microbiome studies, distinguishing true signal from contamination is paramount:

Negative and Positive Controls: Inclusion of extraction controls, no-template amplification controls, and positive controls with known microbial compositions helps identify contamination sources and assess technical variability [1].

Bioinformatic Decontamination: Computational approaches including frequency-based filtering, prevalence-based methods, and machine learning techniques help identify and remove potential contaminants by leveraging patterns indicative of contamination rather than biological signal [8].

Indicator Molecules: Detection of molecules unlikely to survive in viable microbes (such as certain RNAs or labile metabolites) can help distinguish between living residents and non-viable contaminants or DNA fragments [1].

Research Reagent Solutions and Experimental Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Sterile Site Microbiome Research

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | MoBio PowerSoil, DNeasy Blood & Tissue | DNA isolation from low-biomass samples | Optimization needed for different sample types; includes controls for contamination |

| 16S rRNA Primers | 515F-806R (V4), 27F-338R (V1-V2) | Amplification of bacterial taxonomic markers | Selection affects taxonomic coverage and resolution |

| Shotgun Library Prep | Illumina Nextera, KAPA HyperPrep | Preparation of sequencing libraries | Optimized for low-input DNA crucial for sterile sites |

| Contamination Control | DNase/RNase removal reagents, UV irradiation | Reduction of external DNA contamination | Critical for low-biomass studies |

| Positive Control Standards | ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standards | Assessment of technical variability | Known composition communities for benchmarking |

| Storage/Preservation | RNA/DNA Stabilization Tubes, Freezing at -80°C | Sample integrity maintenance | Critical between collection and processing |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines | QIIME2, Mothur, DADA2, MEGAN | Data processing and analysis | Standardization enables cross-study comparisons |

Conceptual Framework and Theoretical Implications

The emerging evidence challenging traditional sterility concepts necessitates new conceptual frameworks for understanding host-microbe relationships:

Evolving Paradigms in Host-Microbe Relationships

Innate and Adaptive Genomes: This framework proposes viewing the human innate genome (inherited genetic blueprint) in continuous crosstalk with the adaptive genome (dynamic microbiome), with exploration of their interplay potentially explaining a broader spectrum of individual phenotypic variations [1].

Meta-Host Model: This concept broadens the definition of host to include symbiotic microbes as an integrated biological entity, potentially explaining disease heterogeneity or organ transplantation success rates resulting from host-microbiome interactions [1].

Germ-Free Syndrome: The abnormalities observed in germ-free animals challenge the traditional "microbes as pathogens" view, instead advocating for the necessity of microbes for health, with potential implications for understanding the consequences of absent microbiota in traditionally sterile sites [1].

Slave Tissue Concept: This perspective views microbes as exogenous tissues under the control of human master tissues (nerve, connective, epithelial, muscle), highlighting the dynamic health implications of microbial interactions in various anatomical niches [1].

Conceptual Evolution in Sterile Site Microbiome Research

The investigation of microbiomes in traditionally sterile human sites represents a frontier in microbiome research with profound implications for understanding human physiology and disease. While compelling evidence suggests microbial presence in locations like the vascular system, ocular surface, and potentially the brain, methodological challenges including contamination control, appropriate statistical analysis, and result interpretation remain substantial. Future research directions should include:

Standardized Methodologies: Development and implementation of standardized protocols for sample collection, processing, and analysis specifically optimized for low-biomass environments [8].

Longitudinal Studies: Implementation of longitudinal sampling designs to distinguish between transient and resident communities and understand microbial dynamics in health and disease transitions [1].

Multi-Omics Integration: Combined application of metagenomics, metatranscriptomics, metaproteomics, and metabolomics to move beyond compositional assessment to functional understanding [8].

Experimental Validation: Development of sophisticated animal models and in vitro systems to experimentally validate sequencing findings and establish causal mechanisms [1].

Clinical Translation: Exploration of diagnostic and therapeutic applications, including microbial biomarkers for disease detection or microbial-based interventions for conditions originating in traditionally sterile sites [11].

As research methodologies continue to advance and conceptual frameworks evolve, our understanding of microbial presence in traditionally sterile sites will likely transform fundamental concepts in human anatomy, physiology, and pathology, ultimately contributing to more comprehensive approaches to human health and disease.

The core microbiome represents a fundamental concept in microbial ecology, crucial for understanding the intricate relationship between microbial ecosystems and human health. Traditionally defined through taxonomic overlap—identifying microbial species consistently present across multiple individuals—this approach has provided valuable but limited insights [4]. While useful for establishing baseline microbial composition, taxonomic definitions often fail to capture the functional dynamics and ecological interactions that ultimately determine microbiome stability and host health outcomes [4] [1]. This limitation is particularly evident when considering the substantial functional redundancy across microbial communities, where different species can perform similar ecological roles, making taxonomic presence alone an insufficient predictor of ecosystem function [4].

A paradigm shift is emerging toward understanding the core microbiome through the lens of relational stability, which focuses on persistent microbial interactions rather than merely persistent taxa [4]. This systems biology framework recognizes that stable relationships—not just individual components—signify the core structure of complex adaptive systems like the gut microbiome [4]. By identifying microbial relationships that endure across varying conditions such as dietary interventions or disease states, researchers can better elucidate the fundamental architecture that maintains ecosystem integrity and functionality [4]. This transition from taxonomic to relational definitions represents a significant advancement in microbiome science, with profound implications for predictive modeling, therapeutic development, and personalized medicine.

Theoretical Foundations: From Taxonomy to Relational Stability

Limitations of Taxonomic Overlap Approaches

Conventional approaches to defining the core microbiome have primarily relied on cataloging microbial taxa that are commonly shared across populations [4]. This method assumes that shared presence equates to ecological importance, but this assumption often proves inadequate for several reasons. First, taxonomic labels frequently fail to capture the ecological and functional roles of individual strains, risking the exclusion of key microbial interactions that sustain host health [4]. Second, functional redundancy across microbial communities means that different taxa can perform similar metabolic functions, making presence/absence data insufficient for predicting ecosystem performance [4]. Third, taxonomic approaches typically overlook the strain-level diversity that often determines functional capabilities and host interactions [4].

The practical limitations of taxonomic overlap become evident when considering that core microbiome members identified through this method are indeed commonly shared, but not all commonly shared microbes contribute significantly to critical ecosystem functions [4]. This discrepancy explains why taxon-based approaches often struggle to identify consistent microbial signatures associated with health states across diverse populations, and why therapeutic interventions based solely on taxonomic composition have shown limited success [4].

The Relational Stability Framework

The relational stability framework addresses these limitations by applying systems biology principles to microbiome analysis [4]. This approach is grounded in the fundamental tenet that in complex adaptive systems, stable relationships—not individual components—signify core structure [4]. For the gut microbiome, this implies identifying microbial relationships that endure across varying conditions, such as dietary interventions or disease states [4].

The core methodology involves identifying stably connected genome pairs across diverse conditions [4]. This approach involves constructing co-abundance networks from microbiome data and searching for genome pairs that exhibit stable correlations across different perturbations [4]. These stable genome pairs reflect ecological interactions—including cooperation, competition, and niche sharing—that are essential for maintaining ecosystem integrity [4]. Analysis of 38 microbiome datasets spanning dietary interventions and 15 diseases revealed a consistent Two Competing Guilds (TCG) structure as a core signature, comprising a Foundation Guild (FG) dominated by short-chain fatty acid-producing bacteria and a Pathobiont Guild (PG) enriched with opportunistic pathogens and pro-inflammatory microbes [4].

Table 1: Key Concepts in Relational Stability Framework

| Concept | Definition | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Stably Connected Genome Pairs | Microbial genomes that maintain correlated abundance patterns across diverse conditions | Identifies ecologically significant interactions beyond taxonomic presence |

| Co-abundance Networks | Mathematical representation of microbial abundance correlations | Enables visualization and quantification of microbial relationships |

| Two Competing Guilds (TCG) | Core structure comprising Foundation and Pathobiont Guilds | Represents fundamental functional organization of gut microbiome |

| Foundation Guild (FG) | Microbial consortium specialized in fiber fermentation and SCFA production | Promotes gut barrier integrity, reduces inflammation, maintains metabolic homeostasis |

| Pathobiont Guild (PG) | Microbial consortium with virulence factors and inflammatory potential | Drives inflammation, disrupts metabolic balance, associated with disease states |

Methodological Approaches: Analyzing Microbial Relational Stability

Data Generation and Preprocessing

The analysis of relational stability in microbiome research relies on sophisticated sequencing technologies and careful data processing. The two primary sequencing methods are 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing and metagenomic shotgun sequencing (MSS) [9] [12]. While 16S sequencing provides a cost-effective approach for taxonomic classification, MSS offers greater resolution by sequencing entire genomes, enabling species-level identification and functional profiling [12]. For relational stability analyses, MSS is particularly valuable as it provides the genome-level data required for identifying stable genome pairs [4].

Microbiome data present several analytical challenges that must be addressed during preprocessing, including zero inflation (where up to 90% of counts may be zeros), overdispersion, high dimensionality, and compositional effects [9]. Normalization techniques such as Cumulative Sum Scaling (CSS) and Trimmed Mean of M-values (TMM) are essential to account for variable sequencing depth across samples [9]. Additionally, batch effect correction methods like Remove Unwanted Variation (RUV) and ComBat may be necessary to eliminate technical artifacts [9].

Network Construction and Analysis

The construction of co-abundance networks begins with correlation analysis between microbial abundances. The SparCC algorithm and similar approaches are particularly valuable as they account for compositional data constraints [9]. Once correlation matrices are established, network inference techniques identify significant associations, with stability across conditions determined through permutation testing or cross-validation approaches [4].

The relational stability framework specifically searches for network connections that persist across multiple perturbations or population subsets [4]. In practice, this involves analyzing multiple datasets—spanning different diseases, dietary interventions, or population cohorts—and identifying the microbial interactions that remain statistically significant across these diverse conditions [4]. This cross-condition stability distinguishes core ecological relationships from situation-specific associations.

Experimental Validation and Functional Characterization

The relational stability framework extends beyond computational analysis to experimental validation. Key experimental approaches include gnotobiotic mouse models colonized with defined microbial communities, in vitro culture systems that recapitulate microbial interactions, and metabolomic profiling to verify functional outputs [4] [11]. These validation approaches are essential for establishing causal relationships between stable microbial interactions and host phenotypes.

Functional characterization typically involves metatranscriptomics to assess gene expression patterns, metaproteomics to quantify protein abundance, and metabolomics to measure metabolic outputs [12]. For the TCG model, specific functional assays might quantify short-chain fatty acid production by Foundation Guild members or measure inflammatory potential of Pathobiont Guild members [4]. These functional readouts provide mechanistic links between relational stability and host health outcomes.

Table 2: Key Analytical Methods for Relational Stability Analysis

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Application in Relational Stability |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Technologies | 16S rRNA sequencing, Shotgun Metagenomics | Generate raw microbial abundance data for network construction |

| Normalization Methods | CSS, TMM, TSS, RLE | Account for technical variability and compositional nature of data |

| Network Inference | SparCC, Pearson/Spearman Correlation | Identify significant microbial associations in co-abundance networks |

| Stability Assessment | Cross-validation, Permutation Testing | Determine which network connections persist across conditions |

| Functional Validation | Metabolomics, Metatranscriptomics, Gnotobiotic Models | Verify biological significance of stable relationships |

The Two Competing Guilds Model: A Core Structure Revealed Through Relational Stability

Foundation Guild Characteristics

The Foundation Guild (FG) represents a core functional consortium within the gut microbiome, characterized by dominance of short-chain fatty acid (SCFA)-producing bacteria [4]. Key SCFAs produced by this guild include acetic acid, propionic acid, and butyric acid, which serve multiple host-beneficial functions [4]. Butyrate, in particular, serves as the primary energy source for colonocytes, enhances gut barrier function by strengthening tight junctions, and exhibits anti-inflammatory properties through inhibition of histone deacetylases [4].

From an ecological perspective, FG members typically include taxa such as Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Roseburia species, and other specialized fiber-fermenting bacteria that have co-evolved with human hosts [4]. These taxa often form stable cooperative networks, cross-feeding on metabolic byproducts to maximize energy extraction from dietary fibers [4]. The relational stability analysis revealed that FG members maintain consistent ecological relationships despite dietary variations and other perturbations, underscoring their foundational role in ecosystem integrity [4].

Pathobiont Guild Characteristics

The Pathobiont Guild (PG) comprises microorganisms with potential for virulence factor expression, antibiotic resistance genes, and pro-inflammatory activities [4]. Unlike frank pathogens, pathobionts typically exist as commensals under homeostatic conditions but can promote pathology when their growth goes unchecked or when they translocate across compromised mucosal barriers [4].

PG members produce various metabolites with potential host-detrimental effects, including endotoxins (such as lipopolysaccharide), indole derivatives, and hydrogen sulfide [4]. These compounds can drive systemic inflammation, disrupt gut barrier integrity, interfere with insulin signaling, and promote metabolic dysfunction [4]. The relational stability framework demonstrates that PG members maintain stable associations with each other, forming a coherent functional group that behaves distinctly from the Foundation Guild [4].

Guild Interactions and Ecological Dynamics

The TCG model reveals that Foundation and Pathobiont Guilds typically exist in a dynamic equilibrium, with competitive exclusion and resource competition shaping their ecological relationship [4]. FG members often inhibit PG growth through multiple mechanisms, including SCFA-mediated suppression of virulence gene expression, nutrient competition, and reinforcement of gut barrier function [4]. This competitive relationship explains why these guilds emerge as distinct network modules in relational stability analyses.

The balance between FG and PG has profound implications for host health. Analysis of 38 datasets across 15 diseases revealed that 85% of ecological interactions in the gut microbiome center around TCG members, despite these guilds constituting less than 10% of total microbial membership [4]. This disproportionate influence on network structure positions the TCG as a primary determinant of microbiome stability and function. Removal of FG or PG members significantly disrupts network integrity, confirming their foundational role as the backbone of the gut microbial ecosystem [4].

Research Toolkit: Essential Methods and Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Relational Stability Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina MiSeq/HiSeq, PacBio, Oxford Nanopore | Generate raw sequence data for microbial community analysis |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines | QIIME2, DADA2, Mothur, MetaPhlAn2 | Process raw sequencing data, perform taxonomic assignment |

| Network Analysis Software | SparCC, CoNet, SPIEC-EADI | Construct co-abundance networks from microbial abundance data |

| Statistical Programming | R (phyloseq, vegan, igraph packages), Python | Perform statistical analysis, visualization, and stability testing |

| Reference Databases | GREENGENES, SILVA, KEGG, eggNOG | Taxonomic and functional annotation of microbial sequences |

| Culture Media | Modified YCFA, Gifu Anaerobic Medium | In vitro cultivation of Foundation and Pathobiont Guild members |

| Analytical Standards | SCFA standards (acetate, propionate, butyrate), LPS standards | Quantification of microbial metabolites in validation experiments |

| GN25 | GN25|SNAIL-p53 Inhibitor|For Research | GN25 is a novel SNAIL-p53 interaction inhibitor used in cancer research to reverse EMT and inhibit angiogenesis. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| Leukotriene E4-d5 | Leukotriene E4-d5 Stable Isotope | Leukotriene E4-d5 is a deuterium-labeled internal standard for precise LC/MS or GC/MS quantification of LTE4 in asthma and inflammation research. For Research Use Only. |

Applications and Implications: From Basic Research to Clinical Translation

Predictive Modeling and Diagnostics

The relational stability framework significantly enhances predictive modeling in microbiome research. Using stably connected genomes in TCGs as features substantially improves classification of disease versus control samples and enhances prediction of treatment outcomes compared to models relying solely on taxonomic composition [4]. This approach has demonstrated particular value in predicting responses to immunotherapy, where TCG-based models outperformed conventional taxonomic markers [4] [13].

The Stably Connected Agent Network (SCAN) AI modeling framework capitalizes on relational stability by using stably connected agents as key features for prediction and analysis [4]. In medical applications, SCAN improves the precision of models for diagnosing diseases or predicting treatment outcomes by leveraging stable microbial relationships as indicators of health or disease states [4]. This approach underscores the translational potential of moving beyond taxonomic composition to relational signatures.

Therapeutic Development and Microbiome Engineering

Relational stability opens new avenues for therapeutic development by identifying key ecological relationships that can be targeted for intervention. Rather than attempting to introduce or eliminate specific taxa, microbiome engineering can focus on manipulating the stable relationships that determine ecosystem outcomes [4]. This might involve developing prebiotics that selectively enhance Foundation Guild function, or designing bacteriophage cocktails that specifically target Pathobiont Guild members without disrupting beneficial microbes [11].

Clinical trials building on the relational stability framework are exploring interventions that specifically target the balance between Foundation and Pathobiont Guilds [4] [11]. These include high-fiber dietary interventions to support SCFA production, precision probiotics designed to integrate into existing Foundation Guild networks, and microbiota transplantation protocols that transfer stable microbial relationships rather than just microbial taxa [11]. The TCG model provides a rational framework for designing and evaluating these interventions based on their impact on core ecological dynamics rather than simply taxonomic composition.

The transition from taxonomic overlap to relational stability represents a paradigm shift in how we define and understand the core microbiome. This framework recognizes that stable relationships—not just stable taxa—form the fundamental architecture of microbial ecosystems, with the Two Competing Guilds model providing a concrete example of how this architecture shapes host health [4]. By focusing on persistent microbial interactions that withstand environmental perturbations, relational stability offers a more robust, functional, and clinically relevant definition of what constitutes a "core" microbiome.

The implications of this shift extend beyond basic science to therapeutic development, diagnostic innovation, and personalized medicine [4] [11]. As microbiome research continues to evolve, the relational stability framework provides a powerful approach for identifying intervention targets, predicting health outcomes, and ultimately harnessing the microbiome to improve human health. Future research should further refine our understanding of how these stable relationships establish during early development, how they vary across populations, and how they can be therapeutically manipulated to prevent and treat disease.

The human microbiome, particularly within the gastrointestinal tract, is now recognized as a fundamental regulator of health, influencing processes from digestion and immunity to neurological function [14] [15]. A significant challenge in microbiome research has been defining a "core microbiome"—a set of microbial entities consistently associated with health across diverse populations [16] [4]. Traditional approaches focusing on taxonomic abundance have proven inadequate, as they often conflate beneficial and harmful strains within the same species and fail to account for functional redundancy across taxa [17] [16].

The Two Competing Guilds (TCG) Model represents a paradigm shift from taxonomy to ecology and function. This model identifies two distinct bacterial groups—the Foundation Guild (FG) and the Pathobiont Guild (PG)—that engage in dynamic competition to determine gut ecosystem stability and host health outcomes [18] [4] [19]. A "guild" is defined as a group of bacteria that show consistent co-abundance behavior and likely work together to contribute to the same ecological function, irrespective of their taxonomic classification [17] [20]. This framework provides a universal strategy for identifying core microbiome structures based on stable relational dynamics rather than mere taxonomic presence [4].

Theoretical Framework and Ecological Principles

From Taxonomy to Functional Guilds

Conventional microbiome analysis has relied heavily on collapsing bacterial strains based on nearest-neighbor taxonomy, often leading to controversial and inconsistent results across studies [17] [20]. A prominent example is the decade-long debate over the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes (F/B) ratio in obesity, where meta-analyses ultimately found no consistent relationship [17]. These limitations stem from several critical factors:

- Strain-Level Diversity: Bacterial strains within the same species can exhibit up to 30% difference in their genomic makeup, leading to contrasting phenotypes and host interactions [17] [20].

- Functional Redundancy: Similar ecological functions can be performed by taxonomically distinct organisms [4].

- Database Limitations: Taxonomic approaches often exclude novel bacteria that cannot be classified against existing reference databases [17] [20].

The guild-based approach addresses these limitations by focusing on co-abundance behavior and functional coherence rather than phylogenetic relationships [17]. Members of the same guild cooperate, thrive, or decline together, showing synchronized ecological behavior across different environmental conditions and host states [20].

The Relational Stability Principle

The TCG model is grounded in the principle of relational stability—the concept that core microbiome members maintain consistent functional relationships within the gut ecosystem across diverse conditions [4]. From an evolutionary perspective, these stable relationships represent millennia of co-evolution between humans and their microbiota, forming a foundational structure that withstands various environmental pressures [4].

This principle shifts the focus from cataloging individual taxa to identifying persistent ecological interactions that form the backbone of the microbial ecosystem. Research analyzing 38 microbiome datasets spanning dietary interventions and 15 diseases revealed that TCG members constitute less than 10% of total microbial members yet form the center of 85% of ecological interactions within the gut network [4]. This disproportionate influence confirms their foundational role in maintaining ecosystem integrity.

Defining the Competing Guilds: Characteristics and Functions

Foundation Guild: The Cornerstone of Health

The Foundation Guild represents a consortium of bacteria that serve as structural and functional pillars of the gut ecosystem. These taxa exhibit several defining characteristics:

Table 1: Key Characteristics of the Foundation Guild

| Characteristic | Description | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Metabolic Function | Dietary fiber degradation and fermentation | Produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) including butyrate, acetate, and propionate [18] [4] [19] |

| Ecological Role | Structures and stabilizes the gut microbial network | Forms the backbone of ecological interactions; removal disrupts network integrity [4] [19] |

| Host Benefits | Enhances gut barrier function, reduces inflammation, promotes satiety hormone production | Butyrate serves as energy source for colonocytes; strengthens tight junctions; regulates immune responses [18] [4] [19] |

| Representative Taxa | Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Roseburia spp., and other SCFA-producing bacteria | These species have co-evolved with humans as cooperative partners [4] |

The Foundation Guild's dominance creates an environment that suppresses pathogenic species through multiple mechanisms: competitive exclusion for nutrients and adhesion sites, creation of unfavorable metabolic conditions (e.g., lower pH from SCFA production), and direct enhancement of host defense mechanisms [4] [19].

Pathobiont Guild: Necessary but Potentially Harmful

The Pathobiont Guild comprises bacteria that exist in a symbiotic relationship with the host under normal conditions but can proliferate and become detrimental under certain circumstances:

Table 2: Key Characteristics of the Pathobiont Guild

| Characteristic | Description | Functional Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Output | Production of endotoxins, indole, hydrogen sulfide, and other inflammatory mediators | Promotes systemic inflammation, disrupts gut barrier integrity, contributes to insulin resistance [18] [4] |

| Ecological Role | Necessary in small amounts for immune education and vigilance | Provides tonic stimulation to host immune system; required for proper immune development [18] [19] |

| Disease Association | Ecological dominance linked to chronic inflammatory states | Associated with inflammatory bowel disease, metabolic disorders, neurological conditions, and certain cancers [18] [4] [19] |

| Regulation | Suppressed by Foundation Guild metabolites (SCFAs) and host immune factors | SCFAs inhibit PG growth; gut barrier integrity prevents systemic translocation of PG components [4] |

The Pathobiont Guild's necessary but precarious position in the ecosystem illustrates the complexity of host-microbe relationships. At low abundance, these microbes contribute to immune system education and maintain ecological diversity, but when their population expands beyond a critical threshold, they can drive disease processes [18] [19].

The Seesaw Dynamics of Guild Competition

The TCG model conceptualizes gut health as a dynamic balance between the Foundation and Pathobiont Guilds, often described as a "seesaw" relationship [19]. When the Foundation Guild dominates, gut health is maintained through the mechanisms described above. Conversely, when the balance tips in favor of the Pathobiont Guild, dysbiosis occurs, potentially leading to inflammation that can exacerbate various chronic conditions [18] [19].

This competitive dynamic is primarily mediated through metabolic interference, where Foundation Guild members utilize dietary fibers to produce SCFAs that simultaneously benefit the host and inhibit Pathobiont Guild expansion [4]. The diagram below illustrates these core competitive dynamics:

Methodological Framework: Analytical Approaches and Protocols

Genome-Centric Analysis for Strain-Level Resolution

The TCG model employs a genome-centric analytical approach that overcomes the limitations of traditional taxonomy-dependent methods [20] [19]. This methodology is built on three key pillars:

Genome-Specific Analysis: Utilizes high-quality metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) or amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) as fundamental analytical units, providing near strain-level resolution [20]. Each genome receives a universal unique identifier (UUID) to track its ecological behavior across studies without relying on taxonomic classification [19].

Database-Independent Inclusivity: By assigning UUIDs based on sequence identity rather than taxonomic affiliation, this approach ensures that novel and unclassifiable bacteria are included in analyses, significantly reducing information loss [20].

Interaction-Focused Aggregation: Microbial sequences are grouped into guilds based on co-abundance patterns across samples and conditions, rather than phylogenetic relationships [17] [20].

The experimental workflow below outlines the key steps in guild-based analysis:

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Implementation of the TCG analytical framework requires specific reagents and computational tools:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for TCG Analysis

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Technology | Shotgun metagenomic sequencing platforms | Comprehensive genomic characterization of microbial communities | Prefer long-read technologies for improved assembly; depth >10M reads/sample [20] |

| Genome Assembly | MEGAHIT, metaSPAdes | Assembly of short reads into contigs and metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) | Use multiple assemblers; quality assessment with CheckM [17] |

| Bin Refinement | DAS Tool, MetaBAT2, MaxBin2 | Grouping contigs into MAGs based on sequence composition and abundance | Apply refinement pipelines; aim for >90% completeness, <5% contamination [16] |

| UUID System | Custom UUID generation scripts | Tracking genomes across studies without taxonomic assignment | Enables database-independent analysis [20] [19] |

| Co-abundance Analysis | SparCC, CoNet, FlashWeave | Quantifying coordinated abundance patterns to identify guilds | Network inference with multiple methods; statistical validation [4] |

| Functional Annotation | KEGG, MetaCyc, eggNOG | Predicting functional potential of identified guilds | 40-60% of genes may lack annotation; consider pathway completeness [17] |

Validation Through Cross-Study Analysis

A critical strength of the TCG model is its validation across diverse populations and conditions. Researchers have applied this framework to 38 microbiome datasets spanning dietary interventions and 15 different diseases, consistently identifying the same core guild structure [4]. This cross-study validation confirms that the Foundation and Pathobiont Guilds represent universal ecological units in the human gut, transcending variations in ethnicity, geography, and disease states.

The robustness of guild identification is evaluated using β-diversity matrices of all ASVs or MAGs as a benchmark for the entire information content of the original datasets [20]. Procrustes analysis and Mantel tests are then employed to compare β-diversity matrices before and after data reduction to guild-level variables, ensuring minimal information loss or distortion during the analytical process [20].

Clinical and Therapeutic Implications

Diagnostic and Predictive Applications

The TCG framework provides a powerful approach for classifying health states and predicting treatment outcomes:

- Disease Classification: Artificial intelligence models using stably connected genomes in TCGs as features significantly improve classification of disease versus control samples compared to models based on taxonomic composition alone [4].

- Treatment Response Prediction: The TCG model enhances prediction of personalized responses to immunotherapy across four different diseases, demonstrating its clinical utility beyond gastrointestinal disorders [4] [19].

- Microbiome Health Assessment: The balance between Foundation and Pathobiont Guilds serves as a functional biomarker for gut ecosystem health, transcending the limitations of diversity metrics or taxonomic ratios [16] [4].

Therapeutic Interventions

The TCG model informs targeted therapeutic strategies aimed at restoring Foundation Guild dominance:

Table 4: TCG-Informed Therapeutic Approaches

| Intervention | Mechanism | Application |

|---|---|---|

| Personalized Nutrition | Targeted supplementation with fibers matching Foundation Guild degradation capabilities | Precision diets to support SCFA production and Pathobiont suppression [4] [19] |

| Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) | Direct restoration of Foundation Guild communities | Severe dysbiosis states; requires rigorous donor screening for safety [21] [16] |

| Prebiotic Formulations | Selective stimulation of Foundation Guild growth | Fiber blends targeting SCFA-producing bacteria; inulin, oligosaccharides [21] |

| Probiotic Consortia | Introduction of defined Foundation Guild members | Next-generation probiotics containing keystone SCFA producers [21] |

| Phage Therapy | Selective targeting of dominant Pathobiont species | Precision depletion of pathobionts without broad-spectrum antibiotics [21] |

Safety and Ethical Considerations

Clinical translation of TCG-based therapies requires careful attention to safety and ethical implications. Fecal microbiota transplantation, while effective, has resulted in infections when proper screening protocols were not followed [16]. Rigorous donor screening, standardized preparation methods, and long-term safety monitoring are essential for microbiome-based interventions [21] [16].

Future Directions and Research Agenda

The TCG model opens several promising avenues for future research:

Strain-Resolved Dynamics: Further refinement to strain-level resolution will elucidate functional differences within guilds and enhance personalization [16].

Multi-Omics Integration: Combining metagenomics with metabolomics, proteomics, and host profiling will provide systems-level understanding of guild-host interactions [16] [1].

Longitudinal Studies: Dense temporal sampling will reveal how guild dynamics fluctuate in response to interventions, disease progression, and normal physiological variation [16].

Extrabiblical Guilds: Investigating whether similar competing guild structures exist in other body sites (oral, skin, respiratory) [14] [1].

AI-Driven Causal Inference: Developing machine learning approaches that can establish causal relationships between guild imbalances and specific health outcomes [16].

The Two Competing Guilds model represents a transformative framework for understanding gut microbiome structure and function. By shifting focus from taxonomic classification to ecological roles and relational stability, it provides a universal strategy for identifying core microbiome components essential for human health. The dynamic balance between Foundation and Pathobiont Guilds serves as both a biomarker for health assessment and a target for therapeutic intervention.

As research progresses, the TCG model has the potential to redefine precision medicine approaches for numerous chronic conditions linked to gut dysbiosis. Its validation across diverse populations and conditions underscores its robustness as a foundational framework for future microbiome research and clinical translation.

From Bench to Bedside: Methodologies and Therapeutic Applications for Microbiome Manipulation

The human microbiome, a complex ecosystem of trillions of microorganisms inhabiting various anatomical sites, has co-evolved with humans to play essential roles in metabolism, immunity, and disease prevention [22] [23]. Technological advancements have transformed our understanding of this "hidden organ," which contains over 150 times the genetic material of the human genome [22]. Traditional microbiome studies, primarily focused on microbial composition through 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene sequencing, provided limited insights into functional and mechanistic host-microbiome interactions [22] [23]. The advent of multi-omics technologies—integrating genomics, proteomics, metabolomics—coupled with artificial intelligence (AI) has revolutionized microbiome research, enabling a systems-level understanding of microbial ecology and function [22] [23].

This technological evolution represents a paradigm shift from purely taxonomic descriptions to functional microbiome characterization [23]. Where earlier methods could identify which bacteria were present, integrated multi-omics approaches can now reveal what functions these microbes are performing, how they interact with each other and the host, and what metabolic products they generate [22]. AI and machine learning further enhance this approach by deciphering complex patterns within massive datasets that would be impossible for humans to analyze manually [24] [25]. This comprehensive analytical framework is particularly valuable for understanding microbiome development, distribution, and stabilization across different anatomical sites throughout the human lifespan [1] [11].

The clinical translation of these technological advances is already underway, with applications in precision medicine, drug development, and therapeutic interventions [11] [26]. Microbiome-based diagnostics and therapeutics are increasingly recognized as integral to preventing and treating complex diseases, with the global human microbiome market expected to reach $1.52 billion by 2030 [26]. This growth reflects the expanding recognition that harnessing microbial functions offers unprecedented opportunities for personalized healthcare solutions tailored to an individual's unique microbial composition [22] [11].

Genomic Approaches in Microbiome Research

Metagenomic Sequencing and Analysis

Metagenomics represents a foundational genomic approach in microbiome research, enabling the direct sequencing and analysis of genetic material from entire microbial communities without the need for cultivation [23]. This approach has overcome significant limitations associated with studying unculturable microbial species, which constitute a substantial portion of the human microbiome [23]. Two primary strategies dominate metagenomic sequencing: 16S rRNA sequencing and shotgun metagenomics.

16S rRNA sequencing targets the hypervariable regions of the bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA gene, which contains both conserved and variable regions that serve as fingerprints for taxonomic classification [22]. This method provides a cost-effective approach for profiling microbial community composition and estimating relative abundances of different bacterial taxa [22]. However, it has several limitations, including PCR amplification biases, primer specificity issues, and limited resolution at the species or strain level [23]. Additionally, 16S rRNA sequencing identifies which bacteria are present but provides little information about their functional capabilities [22].

Shotgun metagenomics (shotgunMG) represents a more comprehensive approach by sequencing all DNA fragments in a sample randomly, enabling reconstruction of complete microbial genomes and functional profiles [22] [23]. This method facilitates strain-level identification and can detect microbial genes, pathways, and functional potential [22]. In personalized medicine, shotgunMG offers valuable insights for tailoring interventions based on an individual's unique gut microbiome profile, potentially predicting treatment responses and disease susceptibility [22].

Table 1: Comparison of Genomic Sequencing Approaches in Microbiome Research

| Feature | 16S rRNA Sequencing | Shotgun Metagenomics |

|---|---|---|

| Target Region | 16S rRNA gene hypervariable regions | All genomic DNA in sample |

| Resolution | Genus to species level | Species to strain level |

| Functional Insights | Limited inference from taxonomy | Direct assessment of functional genes |

| Quantification | Relative abundance | Relative abundance with potential for absolute quantification |

| Cost | Lower | Higher |

| Reference Database Dependence | High for taxonomy assignment | High for functional annotation |

| Primary Applications | Microbial community profiling, diversity analysis | Functional potential assessment, pathogen detection |

Metagenomic Workflows and Experimental Protocols

A standardized metagenomic workflow begins with sample collection from the target anatomical site (e.g., gut, skin, oral cavity), followed by DNA extraction using optimized kits that ensure comprehensive lysis of diverse microbial cell types [23]. For 16S rRNA sequencing, PCR amplification of specific hypervariable regions (V1-V9) is performed using primer sets tailored to the research question, followed by library preparation and high-throughput sequencing [23]. For shotgun metagenomics, DNA undergoes fragmentation, size selection, adapter ligation, and library preparation without target-specific amplification [22].

Bioinformatic analysis pipelines process the resulting sequencing data. For 16S rRNA data, this typically involves quality filtering, denoising, amplicon sequence variant (ASV) or operational taxonomic unit (OTU) clustering, taxonomic assignment against reference databases (e.g., SILVA, Greengenes), and diversity analyses [23]. Shotgun metagenomic analysis employs quality control, host DNA removal, de novo assembly or reference-based mapping, gene prediction and annotation, taxonomic profiling, and functional pathway analysis using tools like HUMAnN or MetaPhlAn [22] [27].

The National Microbiome Data Collaborative (NMDC) has developed standardized workflows and data processing tools to enhance reproducibility and interoperability across studies [28] [29]. Their bioinformatics pipeline, NMDC EDGE, provides standardized workflows for processing multi-omics microbiome data, supporting best practices in data stewardship throughout the research lifecycle [28].

Proteomic and Metabolomic Technologies

Metabolomic Profiling in Microbiome Research

Metabolomics provides a direct readout of microbial functional activity by characterizing the complete set of small molecule metabolites (<1,500 Da) produced by microbial communities and their host interactions [22]. These metabolites act as chemical messengers, circulating through the body and influencing metabolism, immunity, and even brain function [24]. Gut microbes produce and modify thousands of metabolites, including short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), bile acids, neurotransmitters, and vitamins, which play crucial roles in host physiology [22] [24].

Two primary analytical platforms dominate metabolomic studies: mass spectrometry (MS) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy [22]. MS-based approaches, particularly liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), offer high sensitivity, broad dynamic range, and the ability to characterize thousands of metabolites simultaneously [22]. NMR spectroscopy provides advantages in quantitative accuracy, minimal sample preparation, and structural elucidation capabilities, though with generally lower sensitivity than MS [22].

Metabolomic workflows begin with careful sample collection (feces, blood, urine) and immediate quenching of metabolic activity to preserve the in vivo metabolic state [27]. Sample extraction employs methods like methanol precipitation or methyl-tert-butyl ether liquid-liquid extraction to recover diverse metabolite classes [22]. Following instrumental analysis, raw data processing includes feature detection, alignment, normalization, and metabolite identification using databases such as HMDB, METLIN, and MassBank [22]. Statistical analysis then identifies differentially abundant metabolites associated with specific microbial communities or host phenotypes.

In athletic performance research, metabolomic profiling has revealed distinct metabolic adaptations between different types of athletes. A study of Colombian elite athletes found that weightlifters showed elevated carnitine, amino acid, and glycerolipid levels compared to cyclists, suggesting energy system-specific metabolic adaptations tailored to their athletic disciplines [27]. These findings underscore how microbiome-influenced metabolomic profiles can reflect specialized physiological demands.

Proteomic Analysis of Microbial Communities

Proteomic approaches characterize the complete set of proteins expressed by microbial communities and host cells in response to microbial interactions, providing direct insight into functional activities and signaling pathways [22]. Microbial proteins include enzymes catalyzing metabolic reactions, structural proteins, and secreted proteins that mediate host-microbe interactions [22].

Mass spectrometry-based proteomics, particularly liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), is the primary technology for large-scale protein identification and quantification [22]. Two main strategies are employed: bottom-up proteomics, which involves protein extraction, enzymatic digestion (typically with trypsin), and LC-MS/MS analysis of resulting peptides; and top-down proteomics, which analyzes intact proteins without digestion [22]. Bottom-up approaches currently dominate due to their higher sensitivity and compatibility with complex mixtures.

Experimental protocols for microbiome proteomics (metaproteomics) begin with protein extraction from fecal or tissue samples using detergent-based lysis buffers [22]. Proteins are digested into peptides, which are then separated by liquid chromatography and analyzed by tandem mass spectrometry [22]. Bioinformatics analysis involves database searching against matched metagenomic sequences or reference databases, protein inference, quantification, and functional annotation [22].

Metaproteomics faces unique challenges, including the complexity of protein mixtures from multiple organisms, dynamic range issues, and the need for matched metagenomic data for accurate protein identification [22]. Despite these challenges, metaproteomics provides crucial functional information that complements other omics approaches by revealing which genetic potentials are actually being expressed and how microbial functions change in response to environmental stimuli [23].

Table 2: Multi-omics Technologies in Microbiome Research

| Technology | Analytical Target | Key Platforms | Information Gained | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metagenomics | DNA | 16S rRNA sequencing, Shotgun sequencing | Microbial composition, genetic potential, phylogenetic relationships | Does not measure functional activity |

| Metatranscriptomics | RNA | RNA-Seq | Gene expression patterns, active metabolic pathways | RNA instability, difficult extraction |

| Metaproteomics | Proteins | LC-MS/MS | Protein expression, enzymatic activities, host-microbe interactions | Complex sample preparation, database dependencies |

| Metabolomics | Metabolites | LC-MS, GC-MS, NMR | Metabolic activities, end products of microbial processes | High variability, complex identification |

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Applications

AI-Driven Pattern Recognition in Microbiome Data

Artificial intelligence, particularly machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL), has become indispensable for analyzing the immense complexity of multi-omics microbiome data [24] [25]. These approaches can identify subtle, non-linear patterns and interactions within high-dimensional datasets that traditional statistical methods often miss [24]. ML algorithms learn from training data to recognize complex relationships between microbial features and host phenotypes, enabling predictions about disease states, treatment responses, and ecological dynamics [25].

Various ML approaches are applied to microbiome research, including supervised learning for classification and regression tasks (e.g., predicting disease status from microbial features), unsupervised learning for clustering and dimensionality reduction (e.g., identifying microbial enterotypes), and semi-supervised learning that leverages both labeled and unlabeled data [25]. Deep learning models, such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and recurrent neural networks (RNNs), can automatically learn hierarchical feature representations from raw sequencing data or spectral profiles [25].

A notable advancement is the development of specialized AI tools like VBayesMM, a Bayesian neural network that identifies genuine biological relationships between bacterial groups and metabolites while quantifying uncertainty in its predictions [24]. This system has outperformed traditional models in studies of obesity, sleep disorders, and cancer, demonstrating how AI can extract meaningful biological insights from complex microbiome datasets [24]. The Bayesian approach is particularly valuable for microbiome data because it explicitly models uncertainty, helping prevent overconfident but incorrect conclusions that can arise from noisy or incomplete data [24].

AI Applications in Microbial Communication and Ecology

AI approaches are revolutionizing our understanding of microbial communication and ecology by decoding how gut microbes interact with each other and with their human host through chemical signals [24] [25]. Researchers at the University of Tokyo applied AI to map relationships between specific bacterial groups and metabolites, moving closer to understanding how to manipulate these interactions for therapeutic benefits [24]. Their system analyzes which bacterial families significantly influence particular metabolites, providing clues about how to grow specific bacteria to produce beneficial metabolites or design targeted therapies that modify these metabolites to treat diseases [24].

Beyond human health, AI is being applied to environmental microbiome ecosystems. Researchers at Oregon State University are using deep learning to analyze oceanic microbial ecosystems, particularly focusing on methane seeps off the coast of Oregon and Washington [25]. This research aims to identify the role of unknown genes in global biogeochemical cycles by developing AI models that categorize genes into pathways and predict functions of unknown genes based on protein sequences and text-based data [25]. This demonstrates how AI approaches developed for human microbiome research can be adapted to diverse ecological contexts.