Longitudinal Microbiome Data Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide to Time-Series Methods for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive overview of methodological considerations and computational tools for analyzing longitudinal microbiome data.

Longitudinal Microbiome Data Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide to Time-Series Methods for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of methodological considerations and computational tools for analyzing longitudinal microbiome data. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers foundational concepts, specialized analytical techniques including supervised machine learning and multi-way decomposition methods, troubleshooting for common statistical challenges, and comparative validation of approaches. The guide addresses critical aspects from study design and data preprocessing to interpreting dynamic host-microbiome interactions, with emphasis on applications in disease progression, therapeutic interventions, and personalized medicine.

Understanding Longitudinal Microbiome Dynamics: Core Concepts and Exploratory Approaches

Defining Longitudinal Microbiome Data and Its Unique Value Proposition

Longitudinal microbiome data is defined as abundance data from individuals collected across multiple time points, capturing both within-subject dynamics and between-subject differences [1]. Unlike cross-sectional studies that provide a single snapshot, longitudinal studies characterize the inherently dynamic nature of microbial communities as they adapt to host physiology, environmental exposures, and interventions over time [2] [3]. This temporal dimension provides unique insights into microbial trajectories, successional patterns, and dynamic responses that are fundamental to understanding the microbiome's role in health and disease [4] [5].

The unique value proposition of longitudinal microbiome data lies in its ability to capture temporal processes and within-individual dynamics that are invisible to cross-sectional studies. These data enable researchers to move beyond correlation to establish temporal precedence, identify critical transition periods, model causal pathways, and understand the stability and resilience of microbial ecosystems [3] [5]. For drug development professionals, this temporal understanding is particularly valuable for identifying optimal intervention timepoints, understanding mechanism of action, and discovering microbial biomarkers that predict treatment response [2].

Key Characteristics and Analytical Challenges

Longitudinal microbiome data present several unique characteristics that necessitate specialized analytical approaches, compounding the challenges already present in cross-sectional microbiome data [3] [6].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Longitudinal Microbiome Data and Associated Challenges

| Characteristic | Description | Analytical Challenge |

|---|---|---|

| Time Dependency | Measurements from the same subject are correlated across time points [1] | Requires specialized correlation structures (AR1, CAR1); standard independent error assumptions violated [1] |

| Compositionality | Data represent relative proportions constrained to a constant sum [3] [7] | Relative abundance trends do not equate to real abundance trends; spurious correlations [3] [7] |

| Zero-Inflation | 70-90% zeros due to physical absence or undersampling [3] [6] | Microorganism-specific or time-specific sparsity patterns; distinguishes structural vs. sampling zeros [1] |

| Over-Dispersion | Variance exceeds mean in count data [1] [3] | Poisson models inadequate; requires negative binomial or zero-inflated models with dispersion parameters [1] [3] |

| High-Dimensionality | Hundreds to thousands of taxa with small sample sizes [1] [3] | Ultrahigh-dimensional data with more features than samples; low prediction accuracy [1] [3] |

| Temporal Irregularity | Uneven spacing and missing time points, especially in human studies [1] [3] | Interpolation needed; cannot assume balanced design [1] [3] |

These characteristics collectively create analytical challenges that require specialized statistical methods beyond conventional longitudinal approaches. The compositional nature is particularly critical, as ignoring this property can lead to spurious results because relative abundance trends do not equate to real abundance trends [3] [7]. The high dimensionality combined with small sample sizes creates an "ultrahigh-dimensional" scenario where the number of features grows exponentially with sample size [3].

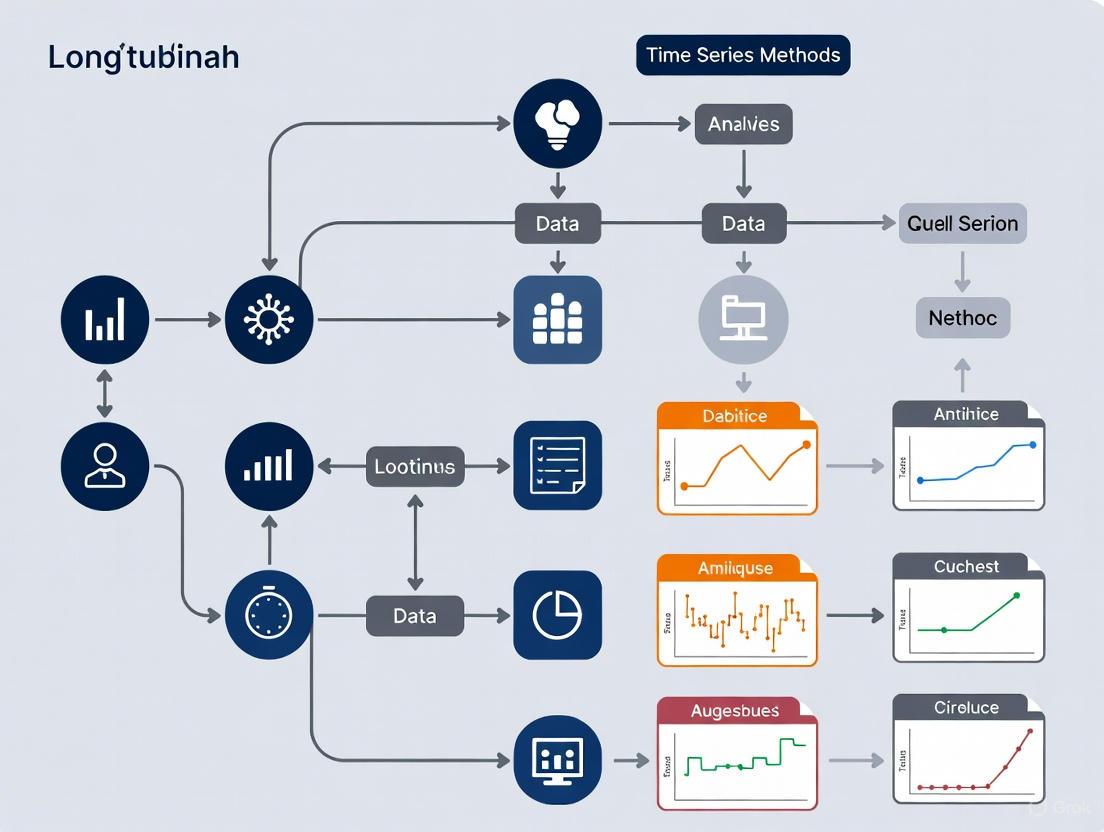

Figure 1: Comprehensive Workflow for Longitudinal Microbiome Studies. This diagram outlines the key stages from study design through interpretation, highlighting critical decision points (red) and methodological options (green) at each phase.

Core Analytical Objectives and Methodologies

Longitudinal microbiome studies typically address three main analytical objectives, each with specialized methodological approaches [1].

Differential Abundance Analysis

The first objective identifies microorganisms with differential abundance over time and between sample groups, demographic factors, or clinical variables [1]. This addresses questions about how microbial abundance changes in response to interventions, disease progression, or environmental exposures.

Protocol 3.1.1: Longitudinal Differential Abundance Analysis using Zero-Inflated Mixed Models

Purpose: To identify taxa whose abundances change significantly over time and/or between groups while accounting for longitudinal data structure.

Materials: R statistical environment, NBZIMM or FZINBMM package [3] [6]

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Convert raw count data to appropriate format with subject IDs, time points, and covariates

- Model Specification:

- Fixed effects: Time, group, time × group interaction, clinical covariates

- Random effects: Subject-specific intercepts to account for repeated measures

- Error structure: Auto-regressive (AR1) or continuous-time AR1 for within-subject correlations [1]

- Model Fitting: Implement negative binomial zero-inflated mixed model with dispersion parameter

- Hypothesis Testing: Test fixed effects using Wald or likelihood ratio tests with multiple testing correction

- Validation: Check model assumptions, residuals, and influential observations

Interpretation: Significant time × group interaction indicates differential trajectories between groups. Covariate effects indicate associations with clinical variables.

Temporal Trajectory Clustering

The second objective identifies groups of microorganisms that evolve concomitantly across time, revealing coordinated ecological dynamics [1].

Table 2: Methodological Approaches for Longitudinal Microbiome Analysis

| Analytical Objective | Methodological Approach | Key Methods | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Abundance | Mixed models with random effects | ZIBR, NBZIMM, FZINBMM [3] [6] | Treatment response, disease progression studies |

| Trajectory Clustering | Distance-based clustering of temporal patterns | Spline models, linear mixed models [1] | Identifying co-evolving microbial groups |

| Network Inference | Conditional independence with sequential modeling | LUPINE [8] | Microbial ecology, interaction dynamics |

| Compositional Analysis | Log-ratio transformations | coda4microbiome [7] | All analyses requiring compositional awareness |

| Machine Learning Prediction | Ensemble methods with feature selection | LP-Micro (XGBoost, neural networks) [2] | Biomarker discovery, clinical outcome prediction |

Microbial Network Inference

The third objective constructs microbial networks to understand temporal relationships and biotic interactions between microorganisms [1] [8]. These networks can reveal positive interactions (cross-feeding) or negative interactions (competition) that structure microbial communities.

Protocol 3.3.1: Longitudinal Network Inference using LUPINE

Purpose: To infer microbial association networks that capture dynamic interactions across time points

Materials: R statistical environment, LUPINE package [8]

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing: CLR transform compositional data, handle zeros with appropriate replacement

- Dimension Reduction: For each taxon pair, compute first principal component of remaining taxa as control variables

- Partial Correlation Estimation: Calculate pairwise partial correlations conditional on control variables

- Sequential Modeling: Incorporate information from previous time points using PLS regression for multiple blocks

- Network Construction: Apply significance threshold to partial correlations to create binary adjacency matrix

- Network Comparison: Calculate stability, centrality, or other graph metrics across time or between groups

Interpretation: Edges represent significant conditional dependencies between taxa. Network changes over time reflect ecological reorganization. Cluster analysis reveals functional modules.

Figure 2: Three Core Analytical Objectives in Longitudinal Microbiome Studies. Each objective addresses distinct research questions and generates unique biological insights, from biomarker discovery to ecological mechanisms.

Advanced Methodological Frameworks

Machine Learning for Predictive Modeling

Machine learning approaches for longitudinal microbiome data integrate feature selection with predictive modeling to identify microbial signatures of clinical outcomes [2].

Protocol 4.1.1: LP-Micro Framework for Predictive Modeling

Purpose: To predict clinical outcomes from longitudinal microbiome data using machine learning with integrated feature selection

Materials: Python or R environment, LP-Micro implementation [2]

Procedure:

- Feature Screening: Apply polynomial group lasso to select taxa with predictive trajectories

- Model Training: Implement ensemble of machine learning methods (XGBoost, RF, SVM) and deep learning architectures (LSTM, GRU, CNN-GRU)

- Ensemble Learning: Combine predictions from multiple models to stabilize performance

- Interpretation: Calculate permutation importance scores and p-values to quantify feature effects

- Validation: Assess performance on held-out test data using AUC, accuracy, or other relevant metrics

Interpretation: Important taxa represent microbial signatures predictive of clinical outcomes. Critical time points indicate windows of maximum predictive information.

Compositional Data Analysis Framework

The compositional nature of microbiome data requires specialized approaches that account for the relative nature of the information [7].

Protocol 4.2.1: Compositional Analysis with coda4microbiome

Purpose: To identify microbial signatures while properly accounting for compositional constraints

Materials: R environment, coda4microbiome package [7]

Procedure:

- Log-Ratio Transformation: Compute all pairwise log-ratios to extract relative information

- Penalized Regression: Apply elastic-net penalization (L1 + L2) to the all-pairs log-ratio model

- Model Selection: Use cross-validation to identify optimal penalization parameters

- Signature Extraction: Express selected model as a balance between groups of taxa

- Longitudinal Extension: For longitudinal data, compute area under log-ratio trajectories

Interpretation: The microbial signature represents a balance between two groups of taxa. For longitudinal data, the signature captures differential trajectory patterns between groups.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Longitudinal Microbiome Studies

| Category | Item | Function | Example Tools/Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Modeling | Zero-inflated mixed models | Accounts for sparsity and repeated measures | ZIBR, NBZIMM, FZINBMM [3] [6] |

| Compositional Analysis | Log-ratio transforms | Handles compositional constraints | coda4microbiome, CLR transformation [3] [7] |

| Network Inference | Conditional independence | Infers microbial interactions | LUPINE, SpiecEasi [8] |

| Machine Learning | Ensemble predictors | Predicts clinical outcomes | LP-Micro (XGBoost, neural networks) [2] |

| Feature Selection | Group lasso | Selects taxonomic trajectories | Polynomial group lasso [2] |

| Data Preprocessing | Normalization methods | Handles sequencing depth variation | Cumulative sum scaling, rarefaction [3] |

| CCR1 antagonist 10 | CCR1 antagonist 10, CAS:1010731-97-1, MF:C32H39ClN2O3, MW:535.125 | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| m-PEG10-azide | m-PEG10-azide, CAS:2112738-12-0, MF:C21H43N3O10, MW:497.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Application Notes and Case Studies

Case Study: Pioneer 100 Wellness Project

The Pioneer 100 study exemplified the value of longitudinal microbiome data in understanding host-microbiome relationships in a wellness context [4]. Researchers analyzed gut microbiomes of 101 individuals over three quarterly time points alongside clinical chemistries and metabolomic data.

Key Findings:

- Identified distinct subpopulations with Bacteroides-dominated versus Prevotella-dominated communities

- Established correlations between these taxa and serum metabolites including fatty acids

- Discovered rare direct transitions between Bacteroides and Prevotella states, suggesting ecological barriers

- Demonstrated alignment of Bacteroides/Prevotella dichotomy with inflammation and dietary markers

Methodological Implications: This study highlighted the importance of longitudinal sampling for identifying stable states and transition barriers in microbial ecosystems, with implications for targeted interventions that require understanding of permissible paths through ecological state-space [4].

Case Study: Predicting Growth Faltering in Preterm Infants

Longitudinal microbiome analysis enabled early identification of preterm infants at risk for growth faltering through integration of clinical and microbiome data [9]. This application demonstrates the clinical translation potential of longitudinal microbiome monitoring for precision nutrition interventions.

Longitudinal microbiome data provides unique insights into the dynamic processes shaping microbial ecosystems and their interactions with host health. The specialized methodologies required for these data—accounting for compositionality, sparsity, over-dispersion, and temporal correlation—enable researchers to address fundamental questions about microbial dynamics, ecological relationships, and clinical predictors. As methodological frameworks continue to evolve, particularly in machine learning and network inference, the value proposition of longitudinal microbiome studies will expand, offering new opportunities for biomarker discovery, intervention optimization, and mechanistic understanding in microbiome research.

Longitudinal microbiome studies, which involve repeatedly sampling microbial communities from the same host or environment over time, are fundamental for understanding microbial dynamics, stability, and their causal relationships with health outcomes. However, the statistical analysis of these time-series data presents unique and interconnected challenges that, if ignored, can lead to spurious results and invalid biological conclusions. Three properties of microbiome data are particularly problematic: autocorrelation, the dependence of consecutive measurements in time; compositionality, the constraint that data represent relative, not absolute, abundances; and sparsity, the high frequency of zero counts due to undetected or truly absent taxa. This article delineates these core challenges within the context of longitudinal analysis, providing a structured guide to their identification, the statistical pathologies they induce, and robust methodological solutions for researchers and drug development professionals.

The Challenge of Autocorrelation

Definition and Underlying Causes

In longitudinal microbiome studies, autocorrelation (or temporal dependency) refers to the phenomenon where measurements of microbial abundance taken close together in time are more similar to each other than those taken further apart [10]. This statistical dependency arises from genuine biological and ecological processes. Microbial communities exhibit inertia, where the community state at time t is intrinsically linked to its state at time t-1 due to factors like population growth dynamics, ecological succession, and stable host-microbiome interactions that persist over time.

Associated Statistical Pathologies

The primary pathology induced by autocorrelation is the violation of the independence assumption that underpins many standard statistical models (e.g., standard linear regression, t-tests). Treating autocorrelated observations as independent leads to a critical miscalculation of the effective sample size, artificially inflating the degrees of freedom [10]. Consequently, standard errors of parameter estimates are underestimated, leading to an inflated Type I error rate (false positives). This risk is starkly illustrated by the high incidence of spurious correlations observed between independent random walks, as demonstrated in [10]. A researcher might identify a statistically significant correlation between two taxa that appears biologically compelling, when in reality the correlation is a mere artifact of their shared temporal structure.

Analytical Framework and Solutions

Addressing autocorrelation requires specialized time-series分æžæ–¹æ³• that explicitly model the dependency structure.

- Model-Based Approaches: A powerful approach is the use of autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) models with Poisson errors, fit with elastic-net regularization [11]. This model, expressed as

log(μ_t) = O_t + ϕ_1 X_{t-1} + ... + ϕ_p X_{t-p} + ε_t + θ_1 ε_{t-1} + ... + θ_q ε_{t-q}, captures the autoregressive (AR) and moving average (MA) components of the time series. The inclusion of an elastic-net penalty (λ_1 ||β||_2^2 + λ_2 ||β||_1) is crucial for dealing with the high dimensionality of microbiome data, as it performs variable selection and shrinks coefficients to produce robust, interpretable models of microbial interactions [11]. - Analysis of Residuals: Instead of analyzing raw abundance time-series, one can analyze the residuals—the point-to-point differences (Δxi(t) = xi(t + Δt) - x_i(t)) [10]. This process of "differencing" the data can remove the autocorrelation structure, allowing for the application of correlation measures on the now-independent residuals.

- Specialized Longitudinal Methods: For other analytical goals, methods like

coda4microbiomeuse summaries of log-ratio trajectories (e.g., the area under the curve) as the input for penalized regression, thereby condensing the temporal information into a predictive signature [7]. Furthermore, novel frameworks are being developed to identify time-lagged associations between longitudinal microbial profiles and a final health outcome using group penalization [12].

Table 1: Summary of Solutions for Addressing Autocorrelation.

| Solution Approach | Key Methodology | Primary Use Case | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Penalized Poisson ARIMA | ARIMA model with Poisson errors & elastic-net regularization [11] | Inferring microbial interactions from count data | Handles count nature, compositionality, and high dimensionality |

| Residual Analysis | Calculating and analyzing point-to-point differences (Δx_i(t)) [10] | Identifying correlations free of spurious temporal effects | Removes autocorrelation, revealing independent associations |

| Trajectory Summary | Using area under log-ratio trajectory in penalized regression [7] | Predicting an outcome from longitudinal data | Condenses complex time-series into a powerful predictive feature |

Experimental Protocol: Inferring Interactions with Penalized Poisson ARIMA

Objective: To infer robust, putative ecological interactions between microbial taxa from longitudinal 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing count data.

Workflow:

- Data Preparation: Compile a count table (taxa as rows, time points as columns) and a metadata table specifying sampling times and total read depth per sample.

- Model Specification: For each focal taxon, specify a Poisson ARIMA model. The offset (O_t) should be the log of the total read count for the sample at time t.

- Model Fitting: Use an elastic-net penalized regression algorithm (e.g.,

glmnetin R) to fit the model. Perform k-fold cross-validation to select the optimal values for the penalization parameters,λandα. - Network Construction: Extract the non-zero coefficients (ϕ) for the lagged abundances of other taxa. These coefficients represent the direction and strength of putative interactions. Construct an interaction network where nodes are taxa and edges are defined by the non-zero coefficients.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps in this protocol:

The Challenge of Compositionality

Definition and Underlying Causes

Microbiome sequencing data are inherently compositional. This means the data are constrained to a constant sum (the total sequencing depth or library size), and thus only carry relative information [13]. The total number of sequences obtained is arbitrary and determined by the sequencing instrument, not the absolute quantity of microbial DNA in the original sample. Consequently, an increase in the relative abundance of one taxon necessitates a decrease in the relative abundance of one or more other taxa, creating a negative correlation bias [10] [13].

Associated Statistical Pathologies

Analyzing compositional data as if they were absolute abundances leads to severe statistical pathologies, primarily spurious correlations. The inherent negative bias can make it appear that two taxa are negatively correlated when their absolute abundances may be completely independent or even positively correlated [13]. Furthermore, the correlation structure changes unpredictably upon subsetting the data (e.g., analyzing a specific phylogenetic group), as the relative proportions are re-scaled within a new sub-composition [13]. This makes many common analyses, including standard correlation measures, ordination based on Euclidean distance, and differential abundance testing using non-compositional methods, highly susceptible to false discoveries.

Analytical Framework and Solutions

The field of Compositional Data Analysis (CoDA) provides a mathematically sound framework for analyzing relative data by focusing on log-ratios between components [7] [13] [14].

- Log-Ratio Transformations: The core CoDA operation is transforming the composition into log-ratios. Common transformations include:

- Centered Log-Ratio (CLR):

CLR(x_i) = ln(x_i) - (1/n) * Σ ln(x_k)[10]. This transformation centers the data by the geometric mean of the composition. While useful, the resulting values are still sum-constrained. - Additive Log-Ratio (ALR):

ALR(x_i) = ln(x_i) - ln(x_focal)[10]. This transforms data relative to a chosen reference taxon. - All-Pairs Log-Ratio (APLR): A powerful approach for prediction involves building a model containing all possible pairwise log-ratios (

log(X_j / X_k)) and using penalized regression (e.g., elastic-net) to select the most informative ratios for predicting an outcome [7].

- Centered Log-Ratio (CLR):

- Log-Constrast Models: After variable selection in an APLR model, the final model can be reparameterized into a log-contrast model: a log-linear model where the sum of the coefficients is constrained to zero [7]. This zero-sum constraint ensures the analysis is invariant to the compositional nature of the data.

- Compositionally Aware Tools: Tools like

ALDEx2,ANCOM, andcoda4microbiomeare explicitly designed within the CoDA framework and should be preferred for differential abundance analysis over methods that ignore compositionality [7] [15].

Table 2: Summary of Solutions for Addressing Compositionality.

| Solution Approach | Key Methodology | Primary Use Case | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) | CLR(x_i) = ln(x_i) - mean(ln(x)) [10] |

General preprocessing for PCA, clustering | Symmetric, does not require choosing a reference |

| All-Pairs Log-Ratio (APLR) | Penalized regression on all log(X_j/X_k) [7] |

Predictive modeling & biomarker discovery | Identifies the most predictive log-ratios for an outcome |

| Log-Contrast Models | Linear model with zero-sum constraint on coefficients [7] | Final model interpretation | Ensures invariance principle of CoDA is met |

Experimental Protocol: Dynamic Microbial Signature with coda4microbiome

Objective: To identify a dynamic microbial signature from longitudinal data that predicts a binary outcome (e.g., disease status).

Workflow:

- Data Preprocessing: Start with a filtered taxa count table and metadata. Calculate the CLR transformation for all taxa at each time point.

- Create Pairwise Log-Ratios: For each sample and time point, compute the trajectory of all possible pairwise log-ratios (

log(Taxon_A / Taxon_B)over time. - Summarize Trajectories: Calculate a summary statistic for each log-ratio trajectory per sample, such as the Area Under the Curve (AUC).

- Penalized Regression: Construct a model where the outcome (e.g., disease status) is regressed against the matrix of all log-ratio AUCs using an elastic-net penalized logistic regression (

glmnet). Cross-validation is used to select the optimal penaltyλ. - Signature Interpretation: The final model will contain a subset of non-zero coefficients for specific log-ratios. This signature can be interpreted as a balance between two groups of taxa: those in the numerator (positive coefficients) and those in the denominator (negative coefficients) that are predictive of the outcome [7].

The following workflow diagram illustrates this compositional analysis protocol:

The Challenge of Sparsity

Definition and Underlying Causes

Sparsity in microbiome data refers to the high percentage of zero counts in the taxon count table, often ranging from 80% to 95% [15]. These zeros can arise from two primary sources: biological zeros (the taxon is truly absent from the sample) and technical zeros (the taxon is present but undetected due to limited sequencing depth, PCR bias, or other methodological artifacts) [15]. A particularly problematic manifestation is group-wise structured zeros, where a taxon has all zero counts in one experimental group but non-zero counts in another [15].

Associated Statistical Pathologies

The preponderance of zeros violates the distributional assumptions of many standard models. It leads to overdispersion (variance greater than the mean) and can cause severe power loss in statistical tests. Group-wise structured zeros present a specific challenge known as perfect separation in regression models, which results in infinite parameter estimates and wildly inflated standard errors, often rendering such taxa non-significant by standard maximum likelihood inference [15]. Furthermore, zeros complicate the calculation of log-ratios, as the logarithm of zero is undefined.

Analytical Framework and Solutions

A multi-faceted approach is required to manage data sparsity effectively.

- Strategic Filtering: An essential first step is to filter out low-prevalence taxa that are unlikely to be informative. This reduces the multiple testing burden and the noise from potential sequencing artifacts [15].

- Zero-Inflated and Penalized Models:

- For zero-inflation: Models like DESeq2-ZINBWaVE use observation weights derived from a Zero-Inflated Negative Binomial (ZINB) model to account for the excess zeros, providing better control of false discovery rates [15].

- For group-wise structured zeros: The standard DESeq2 algorithm, which uses a ridge-type (â„“2) penalized likelihood, is effective at providing finite parameter estimates and stable inference for taxa with perfect separation [15]. A combined pipeline that runs both DESeq2-ZINBWaVE and DESeq2 can comprehensively address both general zero-inflation and group-wise structured zeros.

- Zero-Handling in CoDA: For CoDA methods, zeros must be addressed prior to log-ratio transformation. This can involve replacing zeros with a small pseudo-count, though more sophisticated multiplicative replacement strategies are preferred within the CoDA community [13].

Table 3: Summary of Solutions for Addressing Sparsity.

| Solution Approach | Key Methodology | Primary Use Case | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preemptive Filtering | Removing taxa with low prevalence or abundance [15] | Data preprocessing for all analyses | Reduces noise and multiple testing burden |

| ZINBWaVE-Weighted Methods | e.g., DESeq2-ZINBWaVE [15] | Differential abundance with general zero-inflation | Controls FDR by down-weighting likely dropouts |

| Penalized Likelihood | e.g., Standard DESeq2 (ridge penalty) [15] | Differential abundance with group-wise structured zeros | Provides finite, stable estimates for perfectly separated taxa |

Table 4: Key Analytical Tools and Software for Longitudinal Microbiome Analysis.

| Tool/Resource | Function/Brief Explanation | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| coda4microbiome (R) [7] | Identifies microbial signatures via penalized regression on pairwise log-ratios; handles longitudinal data via trajectory summaries. | Predictive modeling, biomarker discovery in cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. |

| DESeq2 / DESeq2-ZINBWaVE (R) [15] | A count-based method for differential abundance analysis. DESeq2's ridge penalty handles group-wise zeros; ZINBWaVE extension handles zero-inflation. | Testing for differentially abundant taxa between groups in the presence of sparsity. |

| glmnet (R) | Fits lasso and elastic-net regularized generalized linear models. The core engine for many penalized regression approaches. | Model fitting for high-dimensional data (e.g., Poisson ARIMA, log-ratio models) [11]. |

| TimeNorm [12] | A normalization method specifically designed for time-course microbiome data, accounting for compositionality and temporal dependency. | Preprocessing of longitudinal data to improve power in downstream differential abundance analysis. |

| Phyloseq (R) [16] | An integrated R package for organizing, analyzing, and visualizing microbiome data. A cornerstone for data handling and exploration. | General data management, alpha/beta diversity analysis, and visualization. |

| ZINQ-L [12] | A zero-inflated quantile-based framework for longitudinal differential abundance testing. A flexible, distribution-free method. | Identifying heterogeneous associations in sparse and complex longitudinal datasets. |

| DADA2 (R) [16] | A non-clustering algorithm for inferring exact amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) from raw amplicon sequencing data. | Upstream data processing to generate the count table from raw sequencing reads. |

Integrated Analysis Workflow

Confronting autocorrelation, compositionality, and sparsity simultaneously requires an integrated analytical workflow. A recommended pipeline for a typical longitudinal microbiome study begins with rigorous upstream processing using tools like DADA2 to generate an ASV table. The data should then be aggressively filtered to remove rare taxa. For the core analysis, researchers should employ compositionally aware methods. For example, one could use a penalized Poisson ARIMA model on the filtered counts to infer interactions, using the total read count as an offset to account for compositionality, while the model's regularization handles sparsity and autocorrelation. In parallel, CLR-transformed data can be used for visualizations like Principal Component Analysis (PCA), which is more appropriate for compositional data than NMDS on non-compositional distances [14]. Finally, differential abundance analysis across groups should be conducted using a combined approach like DESeq2-ZINBWaVE and DESeq2 to robustly handle both zero-inflation and group-wise structured zeros [15].

The challenges of autocorrelation, compositionality, and sparsity are intrinsic to longitudinal microbiome data analysis. Ignoring any one of them can severely compromise the validity of a study's findings. However, as this article outlines, a robust and growing statistical toolkit exists to address these challenges. By adopting a compositional mindset, explicitly modeling temporal dependencies, and implementing careful strategies to handle sparsity, researchers can extract meaningful and reliable biological insights from complex microbiome time-series data. This rigorous approach is fundamental for advancing our understanding of microbial dynamics and for translating microbiome research into tangible applications in drug development and personalized medicine.

Temporal Sampling Considerations and Study Design Best Practices

Temporal sampling is a critical component in longitudinal microbiome research that enables characterization of microbial community dynamics in response to interventions, environmental changes, and disease progression. Unlike cross-sectional studies that provide single timepoint snapshots, longitudinal designs capture the inherent temporal fluctuations of microbial ecosystems, offering insights into stability, resilience, and directional changes [17]. The dense temporal profiling of microbiome studies allows researchers to identify consistent and cascading alterations in response to dietary interventions, pharmaceuticals, and other perturbations [18]. This protocol outlines comprehensive considerations for temporal sampling strategies and study design to optimize data quality, statistical power, and biological relevance in microbiome time-series investigations.

Fundamental Temporal Sampling Considerations

Sampling Frequency and Duration

The sampling frequency and study duration should align with the research questions and expected dynamics of the system under investigation. Key factors influencing these parameters include:

- Intervention Type: Acute interventions (e.g., antibiotic pulses) may require higher frequency sampling immediately post-intervention, while chronic interventions (e.g., dietary modifications) may necessitate sustained monitoring at regular intervals

- Microbial Turnover Rates: Gut microbiota typically exhibit faster turnover compared to other body sites, often warranting sampling multiple times per week [18]

- Phenomenon Timescales: Colonization events, ecological succession, and community stabilization occur across different temporal scales that should inform sampling schemes

- Practical Constraints: Participant burden, sample processing capacity, and budgetary limitations often determine feasible sampling density

Table 1: Recommended Sampling Frequencies for Different Study Types

| Study Type | Minimum Frequency | Recommended Frequency | Total Duration | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dietary Interventions | Weekly | 3-4 times per week [18] | 8-12 weeks | Include pre-intervention baseline and post-intervention washout |

| Antibiotic Perturbations | Every 2-3 days | Daily during intervention | 4-8 weeks | Capture rapid depletion and slower recovery phases |

| Disease Progression | Monthly | Bi-weekly | 6-24 months | Align with clinical assessment timelines |

| Early Life Development | Weekly | 2-3 times per week | 6-36 months | Account for rapid assembly and maturation |

Baseline and Washout Periods

Proper characterization of baseline microbiota and appropriate washout periods are essential for interpreting intervention effects:

- Baseline Period: Collect multiple samples (typically 3-5) over 1-2 weeks before intervention to establish baseline variability and account for intrinsic temporal fluctuations [18]

- Washout Periods: Include sufficient duration (typically 2-4 weeks) after intervention cessation to monitor recovery dynamics and persistence of effects [18]

- Crossover Designs: Implement adequate washout between different interventions to minimize carryover effects, with duration informed by pilot studies or literature

Sample Size and Power Considerations

Longitudinal microbiome studies require careful consideration of sample size at multiple levels:

- Participants: Account for anticipated effect sizes, within-individual correlation, and potential dropout rates

- Timepoints: Balance sampling density with participant burden and analytical complexity

- Technical Replicates: Include replicate sampling or sequencing to quantify technical variability

Experimental Design Protocols

Human Studies Protocol

The following protocol outlines a comprehensive approach for longitudinal human microbiome studies:

Phase 1: Participant Recruitment and Screening

- Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria: Clearly define eligibility criteria, including age range, health status, and lifestyle factors [19]

- Antibiotic Exclusion: Exclude participants with recent antibiotic use (typically within 3-6 months) or document as covariate [20]

- Demographic and Clinical Data: Collect comprehensive metadata including age, sex, BMI, diet, medical history, and medications [19]

- Informed Consent: Obtain appropriate ethical approval and informed consent, specifying sample collection procedures and data sharing intentions

Phase 2: Baseline Monitoring

- Duration: 1-2 weeks pre-intervention

- Sampling Frequency: 3-5 samples across this period to establish baseline variability

- Standardized Collection: Implement consistent sampling time, method, and storage protocols

- Dietary Recording: Document habitual diet and any deviations during baseline

Phase 3: Intervention Period

- Randomization: Implement appropriate randomization procedures for controlled trials

- Blinding: Use double-blinding where feasible to minimize bias

- Dosing Regimen: Clearly document intervention timing, dose, and administration method

- Compliance Monitoring: Implement measures to verify participant adherence (e.g., diaries, biomarkers, compound ingestion tracking) [18]

- Adverse Event Tracking: Document any unintended effects or protocol deviations

Phase 4: Post-Intervention Monitoring

- Washout Duration: Typically 2-4 weeks depending on intervention persistence

- Sampling Density: May decrease frequency while maintaining ability to capture recovery dynamics

- Long-term Follow-up: For some study questions, extended monitoring (months) may be valuable to assess long-term effects

Animal Studies Protocol

Animal models require special considerations for temporal sampling:

Key Considerations for Animal Studies:

- Maternal Effects: Account for vertical transmission of microbiota by cross-fostering or using germ-free animals inoculated with standardized communities [20]

- Cage Effects: Randomize treatments across litters and cages to avoid confounding [20]

- Facility Variations: Acknowledge and document differences in microbiota between animal facilities, as these can significantly impact results [20]

- Standardized Conditions: Control for diet, light cycles, bedding, and other environmental factors that influence microbiota composition

Experimental Approaches to Mitigate Confounding:

- Germ-free Models: Use germ-free animals inoculated with defined microbial communities

- Cross-fostering: Exchange pups between mothers to disrupt maternal transmission patterns

- Co-housing: House animals from different experimental groups to promote microbiota exchange when studying transmissible phenotypes

- Separate Housing: Maintain animals individually to prevent cross-contamination when studying individual microbiotas

Data Collection and Processing Framework

Sample Collection and Storage

Standardized protocols for sample collection, processing, and storage are essential for data quality:

Table 2: Sample Collection and Processing Standards

| Sample Type | Collection Method | Preservation | Storage Temperature | Quality Controls |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fecal | Home collection kits | Immediate freezing or stabilization buffers | -80°C | Document time from collection to freezing |

| Mucosal | Biopsy during endoscopy | Flash freezing in liquid N₂ | -80°C | Standardize anatomical location |

| Saliva | Passive drool or swabs | Stabilization buffers | -80°C | Control for time of day |

| Skin | Swabbing with standardized pressure | Stabilization buffers | -80°C | Standardize sampling location |

Molecular Methods Selection

The choice of molecular method depends on research questions and resources:

- 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing: Economical for large longitudinal studies focusing on taxonomic composition [20]

- Shotgun Metagenomics: Provides functional potential and higher taxonomic resolution [18]

- Metatranscriptomics: Captures actively expressed functions but requires specialized stabilization

- Metabolomics: Complementary approach to characterize functional outputs

Temporal Normalization Methods

Specialized normalization approaches are required for time-series data:

- TimeNorm: A novel normalization method that performs intra-time normalization (within timepoints) and bridge normalization (across adjacent timepoints) [21]

- Compositional Awareness: Account for compositional nature of microbiome data in all analyses

- Batch Effect Correction: Implement measures to minimize and correct for technical variation across sequencing batches

Analytical Considerations for Time-Series Data

Statistical Framework for Temporal Analysis

Longitudinal microbiome data requires specialized analytical approaches:

- Temporal Autocorrelation: Account for non-independence of repeated measures from same individual

- Multiple Comparison Correction: Address high dimensionality with thousands of microbial features

- Compositional Data Analysis: Use appropriate methods that account for relative nature of abundance data

- Missing Data Handling: Implement appropriate approaches for intermittent missing samples or dropouts

Temporal Pattern Classification

Microbial taxa can exhibit distinct temporal patterns that may be categorized as:

- Stable: Minimal fluctuation over time

- Directional: Consistent increase or decrease over study period

- Periodic: Cyclical fluctuations aligned with external factors

- Responsive: Abrupt changes following interventions that may persist or recover

- Stochastic: Unpredictable fluctuations without clear pattern [17]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Longitudinal Microbiome Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Application | Function | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Stabilization Buffers | Sample preservation | Stabilize microbial DNA/RNA at collection | OMNIgene•GUT, RNAlater |

| 16S rRNA Primers | Taxonomic profiling | Amplify variable regions for sequencing | 515F/806R for bacteria [20] |

| ITS Region Primers | Fungal community analysis | Characterize eukaryotic diversity | ITS1F/ITS2R with UNITE database [20] |

| Shotgun Library Prep Kits | Metagenomic sequencing | Prepare libraries for whole-genome sequencing | Illumina DNA Prep |

| TimeNorm Algorithm | Data normalization | Normalize time-series microbiome data [21] | R/Python implementation |

| MC-TIMME2 | Temporal modeling | Bayesian analysis of microbiome trajectories [18] | Custom computational framework |

Reporting Standards and Data Sharing

Comprehensive reporting is essential for reproducibility and meta-analysis:

STORMS Checklist Implementation

The STORMS (Strengthening The Organization and Reporting of Microbiome Studies) checklist provides comprehensive guidelines for reporting microbiome research [19]:

- Abstract: Include study design, body sites, sequencing methods, and key results

- Introduction: Clearly state background, hypotheses, and study objectives

- Methods: Detail participant characteristics, eligibility criteria, sample processing, bioinformatics, and statistical approaches

- Results: Report participant flow, descriptive data, outcome data, and main findings

- Discussion: Discuss limitations, interpretation, and generalizability

Metadata Documentation

Comprehensive metadata collection is crucial for interpreting longitudinal studies:

- Participant Characteristics: Demographics, medical history, diet, medications, lifestyle factors

- Sample Collection: Time, date, method, preservation, storage conditions

- Experimental Procedures: DNA extraction method, sequencing platform, bioinformatics parameters

- Temporal Variables: Season, time since last meal, menstrual cycle phase (if relevant)

Robust temporal sampling strategies and study designs are foundational to advancing microbiome research. By implementing these standardized protocols for sampling frequency, experimental design, data processing, and analytical approaches, researchers can enhance the quality, reproducibility, and biological relevance of longitudinal microbiome studies. The integration of these best practices with emerging computational methods for time-series analysis will continue to elucidate the dynamic relationships between microbial communities and host health, ultimately supporting the development of targeted microbiome-based interventions.

Parallel Factor Analysis (PARAFAC) is a powerful multi-way decomposition method that serves as a generalization of principal component analysis (PCA) to higher-order arrays. Unlike PCA, PARAFAC does not suffer from rotational ambiguity, allowing it to recover pure spectra or unique profiles of components directly from multi-way data [22]. This capability makes it particularly valuable for analyzing complex data structures that naturally form multi-way arrays, such as longitudinal microbiome studies where data is organized by subjects, microbial features, and temporal time points [23].

The mathematical foundation of PARAFAC lies in its ability to decompose an N-way array into a sum of rank-one components. For a three-way array X of dimensions (I, J, K), the PARAFAC model can be expressed as:

Xijk = Σf=1 to F aif bjf ckf + Eijk

where aif, bjf, and ckf are elements of the loading matrices for the three modes, F is the number of components, and Eijk represents the residual array [22]. This trilinear decomposition allows researchers to identify underlying patterns that are consistent across all dimensions of the data, making it particularly suitable for exploring longitudinal microbiome datasets where the goal is to understand how microbial communities evolve over time under different conditions.

PARAFAC Applications in Longitudinal Microbiome Research

The parafac4microbiome R package has been specifically developed to enable exploratory analysis of longitudinal microbiome data using PARAFAC, addressing the need for specialized tools that can handle the unique characteristics of microbial time series data [24]. This package has been successfully applied to diverse microbiome research contexts, demonstrating its versatility across different microbial environments and study designs.

Table: Key Applications of PARAFAC in Microbiome Research

| Application Context | Research Objective | Data Characteristics | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Vitro Ocean Microbiome [24] | Identify time-resolved variation in experimental microbiomes | Daily sampling over 110 days | PARAFAC successfully identified main time-resolved variation patterns |

| Infant Gut Microbiome [23] [24] | Find differences between subject groups (vaginally vs C-section born) | Large cohort with moderate missing data | Enabled comparative analysis despite data gaps; revealed group differences |

| Oral Microbiome (Gingivitis Intervention) [24] | Identify microbial groups of interest in response groups | Intervention study with response groups | Facilitated identification of relevant microbial groups via post-hoc clustering |

The value of PARAFAC for microbiome research lies in its ability to simultaneously capture the complex interactions between hosts, microbial features, and temporal dynamics. By organizing longitudinal microbiome data as a three-way array with dimensions for subjects, microbial abundances, and time points, researchers can utilize the multi-way methodology to extract biologically meaningful patterns that might be obscured in conventional analyses [23]. This approach has proven effective even with moderate amounts of missing data, which commonly occur in longitudinal study designs due to sample collection challenges or technical dropout [23].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

PARAFAC Analysis Protocol for Longitudinal Microbiome Data

The following workflow outlines the standard procedure for applying PARAFAC to longitudinal microbiome datasets using the parafac4microbiome package:

Data Processing and Model Construction

Step 1: Data Cube Processing

The initial data processing step transforms raw microbiome count data into a format suitable for PARAFAC modeling. Using the processDataCube() function, researchers can apply various preprocessing steps to handle common challenges in microbiome data:

This processing step typically includes sparsity filtering to remove low-abundance features, data transformation (such as Center Log-Ratio transformation for compositional data), and appropriate centering and scaling to normalize the data across different dimensions [24].

Step 2: PARAFAC Model Fitting

The core analysis involves creating the PARAFAC model using the parafac() function with careful consideration of the number of components:

Multiple random initializations (typically 10-100) are recommended to avoid local minima in the model fitting process, which uses alternating least squares (ALS) optimization [24] [22].

Step 3: Model Assessment and Validation Comprehensive model assessment is crucial for ensuring biologically meaningful results:

These functions help determine the optimal number of components by evaluating model fit metrics (such as explained variance) and stability across resampled datasets [24].

Step 4: Component Interpretation and Visualization The final step involves interpreting and visualizing the PARAFAC components:

Sign flipping is a common practice to improve component interpretability without affecting model fit, while the visualization function generates comprehensive plots showing the patterns in each mode of the data [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Research Tools for PARAFAC Microbiome Analysis

| Tool/Category | Specific Solution | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Environment | R Statistical Programming | Primary platform for data analysis and modeling |

| PARAFAC Package | parafac4microbiome R package | Specialized implementation of PARAFAC for longitudinal microbiome data [24] |

| Data Processing | processDataCube() function | Handles sparsity filtering, CLR transformation, centering, and scaling of microbiome data [24] |

| Model Fitting | parafac() function | Implements alternating least squares algorithm for PARAFAC model estimation [24] |

| Model Assessment | assessModelQuality() function | Evaluates model fit and helps determine optimal number of components [24] |

| Stability Analysis | assessModelStability() function | Assesses robustness of components via bootstrapping or jack-knifing [24] |

| Visualization | plotPARAFACmodel() function | Generates comprehensive visualizations of all model components [24] |

| Example Datasets | Fujita2023, Shao2019, vanderPloeg2024 | Curated longitudinal microbiome datasets for method validation and benchmarking [24] |

| m-PEG12-acid | m-PEG12-acid, MF:C26H52O14, MW:588.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| m-PEG12-NHS ester | m-PEG12-NHS ester, CAS:756525-94-7, MF:C30H55NO16, MW:685.76 | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Methodological Considerations

Data Structure and Dimensionality

The successful application of PARAFAC to longitudinal microbiome data requires proper data structuring into a three-way array. The standard dimensions include:

- Mode 1 (Subjects): Individual samples, patients, or experimental units

- Mode 2 (Features): Microbial taxa, OTUs, ASVs, or functional annotations

- Mode 3 (Temporal Dimension): Sequential time points of measurement

This three-way structure enables the model to capture complex interactions that would be lost in conventional two-way analyses [23]. The method has demonstrated robustness to moderate missing data, which is particularly valuable in longitudinal study designs where complete data across all time points can be challenging to obtain [23].

Model Selection and Validation

Determining the optimal number of components (F) represents a critical decision point in PARAFAC modeling. The parafac4microbiome package provides two complementary approaches for this purpose:

The assessModelQuality() function works by initializing many models with different random starting points and comparing goodness-of-fit metrics across different numbers of components. Meanwhile, assessModelStability() uses resampling methods (bootstrapping or jack-knifing) to evaluate whether identified components represent stable patterns in the data rather than random artifacts [24].

Interpretation Framework

Interpreting PARAFAC components requires careful examination of all three modes simultaneously:

- Mode 1 (Subject Loadings): Reveals patterns in how individuals or samples express each component

- Mode 2 (Feature Loadings): Identifies microbial taxa or functions associated with each component

- Mode 3 (Temporal Loadings): Uncovers temporal dynamics and progression patterns

The package's visualization functions facilitate this interpretation by generating coordinated plots across all modes, enabling researchers to connect microbial composition with temporal dynamics and subject characteristics [24]. This integrative approach has proven valuable for identifying microbial groups of interest in intervention studies and understanding differential temporal patterns between subject groups [23] [24].

Implementation Example and Code Framework

Complete Analysis Workflow

The following code provides a comprehensive example of implementing PARAFAC analysis for longitudinal microbiome data:

Results Interpretation Framework

The interpretation of PARAFAC results should follow a systematic approach:

- Component Examination: Analyze each component across all three modes simultaneously to identify coherent biological patterns

- Temporal Dynamics: Focus on the temporal loadings (Mode 3) to understand how components evolve over time

- Microbial Signatures: Examine feature loadings (Mode 2) to identify microbial taxa associated with each temporal pattern

- Subject Groupings: Investigate subject loadings (Mode 1) to reveal how individuals cluster based on shared temporal microbial dynamics

- Validation: Compare findings with existing biological knowledge and, when available, validate with external datasets or experimental results

This methodology has been successfully applied across diverse microbiome research contexts, from in vitro experimental systems to human cohort studies, demonstrating its robustness and versatility for exploratory analysis of longitudinal microbiome data [24].

Visualizing Temporal Patterns and Community Dynamics

Longitudinal microbiome studies, characterized by repeated sample collection from the same individuals over time, are invaluable for understanding the dynamic host-microbiome relationships that underlie health and disease [3]. Unlike cross-sectional studies that provide mere snapshots, time-series data can shed light on microbial trajectories, identify important microbial biomarkers for disease prediction, and uncover the dynamic roles of microbial taxa during physiologic development or in response to interventions [3] [25]. The analysis of temporal data, however, warrants specific statistical considerations distinct from comparative microbiome studies [10]. This Application Note provides a structured framework for analyzing and visualizing temporal patterns and community dynamics in microbiome time-series data, with protocols designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

The core challenges in longitudinal microbiome analysis include handling the compositional, zero-inflated, over-dispersed, and high-dimensional nature of the data while properly accounting for autocorrelation structures arising from repeated measurements [3] [10]. Furthermore, real-world data collection often includes irregularities in time intervals, missingness, and abrupt state transitions [3]. This note addresses these challenges through robust normalization techniques, statistical frameworks for temporal analysis, and specialized visualization methods.

Methodological Framework and Normalization Strategies

Data Characteristics and Preprocessing Challenges

Microbiome data present unique properties that must be addressed prior to analysis. The table below summarizes the key characteristics and their implications for longitudinal analysis.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Microbiome Time-Series Data and Analytical Implications

| Characteristic | Description | Analytical Challenge | Common Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compositional Nature | Data represent relative proportions rather than absolute abundances [3]. | Spurious correlations; relative trends may not reflect real abundance changes [3] [10]. | Log-ratio transformations (CLR) [3] [10]. |

| Zero-Inflation | 70-90% of data points may be zeros [3]. | Distinguishing true absence from absence of evidence; reduced statistical power [3]. | Zero-inflated models (ZIBR, NBZIMM) [3]. |

| Overdispersion | Variance exceeds mean in count data [3]. | Poor fit of standard parametric models (e.g., Poisson) [3]. | Negative binomial models; mixed models with dispersion parameters [3]. |

| High Dimensionality | Number of taxa (features) far exceeds sample size [3]. | High false discovery rate; computational complexity; overfitting [3]. | Dimensionality reduction (PCoA); regularized regression. |

| Temporal Autocorrelation | Measurements close in time are not independent [10]. | Invalidates assumptions of standard statistical tests [10]. | Time-series-specific methods; mixed models with random effects for subject and time [3]. |

Normalization Methods for Time-Course Data

Normalization is a critical preprocessing step to correct for variable library sizes and make samples comparable. For time-series data, specialized methods like TimeNorm have been developed to account for both compositional properties and time dependency [21].

TimeNorm employs a two-stage strategy:

- Intra-time Normalization: Normalizes microbial samples under the same condition and at the same time point using common dominant features (those present in all samples) [21].

- Bridge Normalization: Normalizes samples across adjacent time points under the same condition by detecting and utilizing a group of stable features between time points [21].

This method operates under two key assumptions: first, that most features are not differentially abundant at the initial time point between conditions, and second, that the majority of features are not differentially abundant between two adjacent time points within the same condition [21].

Table 2: Comparison of Normalization Methods for Microbiome Data

| Method | Category | Brief Description | Suitability for Time-Series |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Sum Scaling (TSS) | Scaling | Converts counts to proportions by dividing by library size [21]. | Low; not robust to outliers; ignores time structure. |

| Cumulative Sum Scaling (CSS) | Scaling | Sums counts up to a data-driven quantile to calculate normalization factor [21]. | Moderate; designed for microbiome data but not time. |

| Trimmed Mean of M-values (TMM) | Scaling | Weighted mean of log-ratios after excluding extreme features [21]. | Moderate; assumes non-DE features but not time. |

| Relative Log Expression (RLE) | Scaling | Median ratio of each sample to the geometric mean library [21]. | Moderate; similar assumptions to TMM. |

| GMPR | Scaling | Geometric mean of pairwise ratios, designed for zero-inflated data [21]. | Moderate; handles zeros but not time. |

| TimeNorm | Scaling (Time-aware) | Uses dominant features within time and stable features across time [21]. | High; specifically designed for time-course data. |

The following workflow diagram outlines the key decision points and steps for preprocessing and analyzing longitudinal microbiome data.

Experimental Protocols for Core Analytical Tasks

Protocol 1: Community Structure Trajectory Analysis

Purpose: To characterize and visualize overall shifts in microbial community structure over time within and between subjects.

Principle: Ordination methods reduce high-dimensional data into lower-dimensional spaces where the distance between points reflects community dissimilarity. Tracking these points over time reveals trajectories [25].

Procedure:

- Input Data: Normalized (e.g., via TimeNorm) and transformed (e.g., CLR) abundance table.

- Calculate Dissimilarity: Compute a beta-diversity distance matrix (e.g., Aitchison distance for compositional data, Bray-Curtis, UniFrac) between all sample pairs [3].

- Ordination: Perform Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) on the distance matrix.

- Visualization:

- Plot the first two or three PCoA axes.

- Color points by subject ID and connect consecutive time points for each subject with lines to form temporal trajectories [25].

- Ellipses can be drawn to highlight subject-specific clusters.

Expected Outcome: A trajectory plot demonstrating host specificity (distinct clusters per subject) and temporal dynamics (movement within the ordination space). Perturbations (e.g., antibiotics, diet change) may appear as clear deviations from the baseline cluster [25].

Protocol 2: Identifying Periodicity in Taxon Abundance

Purpose: To detect robust, periodic signals in the abundance of individual microbial taxa.

Principle: Non-parametric statistical tests can identify significant frequencies in time-series data without assuming a specific underlying distribution, which is crucial for noisy, non-normal microbiome data [10].

Procedure:

- Input Data: A normalized and transformed abundance table.

- Spectral Analysis:

- For each taxon of interest, apply the Lomb-Scargle periodogram, which is designed for unevenly spaced time-series data [10].

- Identify the dominant frequency (e.g., 24-hour cycle for diel rhythms).

- Significance Testing:

- Compare the power of the observed periodogram against a null model (e.g., based on autoregressive processes or randomly shuffled data) to calculate p-values.

- Correct for multiple hypothesis testing across all tested taxa using the False Discovery Rate (FDR) method.

Expected Outcome: A list of taxa with significant periodic patterns, their period length, and the strength of the periodicity. This can reveal microbes with diel, weekly, or seasonal rhythms.

Protocol 3: Inferring Microbial Interaction Networks

Purpose: To infer potential ecological interactions (e.g., co-operation, competition) between microbial taxa by identifying groups that co-fluctuate over time.

Principle: Correlation-based network inference identifies taxa with similar abundance profiles, suggesting a potential functional relationship or interaction [10] [25]. Due to data compositionality, this must be done with care.

Procedure:

- Input Data: CLR-transformed abundance table to mitigate compositionality [10].

- Calculate Associations: Compute all pairwise correlations between taxa. Use proportional cross-correlation or regularized estimators to improve robustness.

- Sparsification: Apply a significance threshold (FDR-corrected) to the correlation matrix to create a sparse adjacency matrix, retaining only robust associations.

- Network Construction and Analysis:

- Represent taxa as nodes and significant correlations as edges.

- Use a network analysis tool (e.g., igraph in R) to identify network properties and modules (clusters of densely connected taxa) [25].

- Visualization: Visualize the network, coloring nodes by module membership or taxonomy.

Expected Outcome: An interaction network revealing clusters (modules) of bacteria that fluctuate together over time, suggesting co-occurrence patterns and potential ecological guilds [25].

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow from raw data to key insights in a longitudinal microbiome study.

Visualization of Community Evolution

Visualizing the evolution of community structures is essential for interpreting complex temporal dynamics. The "Community Structure Timeline" is an effective method for tracking changes in community membership and individual affiliations over time [26].

Visual Metaphor: Individuals are represented as "threads" that are grouped into "bundles" (communities). The thickness of a bundle represents the size of the community [26].

Construction Workflow:

- Preprocessing: The dynamic network is divided into discrete time steps. A community detection algorithm is run on the network at each time step [26].

- Community Tracking: A combinatorial optimization algorithm assigns a consistent labeling to communities across time steps, minimizing the cost of individuals switching communities, new communities appearing, or existing ones disappearing [26].

- Layout: The visualization is organized with time on the horizontal axis. Communities are stacked vertically at each time point, ordered by an influence factor (e.g., cumulative number of members). Threads (individuals) are routed through the communities to which they belong at each time point [26].

Application to Microbiome Data: This method can be adapted to show the temporal dynamics of microbial taxa (threads) across predefined or inferred ecological clusters (bundles), revealing patterns of stability, succession, and response to perturbation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Reagents for Longitudinal Microbiome Analysis

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA Sequencing | Targeted gene sequencing for cost-effective taxonomic profiling in long-term studies [21]. | Preferred for dense time-series sampling due to lower cost; enables analysis of community structure and dynamics [21] [25]. |

| TimeNorm Algorithm | A novel normalization method for time-course data [21]. | Critical preprocessing step for intra-time and cross-time normalization to correct library size biases while considering time dependency [21]. |

| Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) Transform | A compositional data transformation that stabilizes variance and mitigates spurious correlations [3] [10]. | Applied to normalized data before distance calculation or correlation-based analysis to address the compositional nature of microbiome data [10]. |

| Lomb-Scargle Periodogram | A statistical method for detecting periodicity in unevenly spaced time-series [10]. | Used in periodicity detection protocols to identify diel or other rhythmic patterns in taxon abundance without requiring evenly spaced samples [10]. |

| MicrobiomeTimeSeries R Package | A statistical framework for analyzing gut microbiome time series [25]. | Provides tools for testing time-series properties (stationarity, predictability), classification of bacterial stability, and clustering of temporal patterns [25]. |

| Graph Visualization Software (e.g., Cytoscape, igraph) | Tools for constructing, visualizing, and analyzing microbial interaction networks. | Essential for the final step of network inference protocols to visualize co-fluctuation modules and explore potential ecological interactions [25]. |

| m-PEG4-sulfonic acid | m-PEG4-sulfonic acid, MF:C9H20O7S, MW:272.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| m-PEG5-azide | m-PEG5-azide, MF:C11H23N3O5, MW:277.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Analytical Methods for Microbiome Time-Series: From Theory to Practice

The Microbiome Interpretable Temporal Rule Engine (MITRE) is a Bayesian supervised machine learning method designed specifically for microbiome time-series analysis. It infers human-interpretable rules that link changes in the abundance of microbial clades over specific time windows to binary host status outcomes, such as disease presence or absence [27]. This framework addresses the critical need for longitudinal study designs in microbiome research, which are essential for discovering causal relationships rather than mere associations between microbiome dynamics and host health [27] [3]. Unlike conventional "black box" machine learning methods, MITRE produces models that are both predictive and biologically interpretable, providing a powerful tool for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to identify microbial biomarkers and therapeutic targets [27].

MITRE Performance and Validation

Performance on Real and Semi-Synthetic Data

MITRE has been rigorously validated on semi-synthetic data and five real microbiome time-series datasets. Its performance is on par with or superior to conventional machine learning approaches that are often difficult to interpret, such as random forests [27]. The framework is designed to handle the inherent challenges of microbiome time-series data, including measurement noise, sparse and irregular temporal sampling, and significant inter-subject variability [27].

Table 1: Key Performance Features of the MITRE Framework

| Feature | Description | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Predictive Accuracy | Performs on par or outperforms conventional machine learning (e.g., random forests) [27]. | Provides high accuracy without sacrificing model interpretability. |

| Interpretability | Generates human-readable "if-then" rules linking microbial dynamics to host status [27]. | Enables direct biological insight and hypothesis generation. |

| Bayesian Framework | Learns a probability distribution over alternative models, providing principled uncertainty estimates [27]. | Crucial for biomedical applications with noisy inputs; guards against overfitting. |

| Data Handling | Manages common data challenges like noise, sparse sampling, and inter-subject variability [27]. | Makes the method robust and applicable to real-world longitudinal study data. |

Comparative Analysis with Other Predictive Models

The development of predictive models that link the gut microbiome to host health is an active area of research. For context, other models like the Gut Age Index (GAI) pipeline, which predicts host health status based on deviations from a healthy gut microbiome aging trajectory, have demonstrated balanced accuracy ranging from 58% to 75% for various chronic diseases [28]. MITRE distinguishes itself from such models through its primary focus on modeling temporal dynamics and changes over time within an individual, rather than relying on single time-point snapshots or population-level baselines.

Table 2: Comparison of Microbiome-Based Predictive Models

| Model | Core Approach | Temporal Dynamics | Key Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| MITRE | Bayesian rule learning from time-series data [27]. | Explicitly models temporal windows and trends (e.g., slopes) [27]. | Interpretable rules linking temporal patterns of microbes to host status. |

| Gut Age Index (GAI) | Machine learning regression to predict host age from a single microbiome sample [28]. | Infers a longitudinal process (aging) from cross-sectional data [28]. | A single index (Gut Age Index) representing deviation from a healthy aging baseline. |

| MDSINE | Unsupervised dynamical systems modeling [27]. | Models microbiome population dynamics over time [27]. | Forecasts of future microbiome states, rather than host outcomes. |

Experimental Protocol for Applying MITRE

Input Data Requirements and Preparation

The following protocol details the steps for preparing data and conducting an analysis with the MITRE framework.

Step 1: Data Collection and Input Specification MITRE requires four primary inputs [27]:

- Microbial Abundance Tables: Tables of microbial abundances (e.g., OTUs from 16S rRNA sequencing or species from metagenomics) measured over time for each host subject.

- Host Status: A binary description of each host's status (e.g., healthy/diseased, treated/untreated).

- Static Covariates (Optional): Static host covariates such as gender, diet, or other metadata.

- Phylogenetic Tree: A reference phylogenetic tree detailing the evolutionary relationships among the observed microbes.

Step 2: Ensure Adequate Temporal Sampling Longitudinal study design is critical. MITRE requires a minimum of 3 time points but performs better with at least 6, and preferably 12 or more [27]. For non-uniformly sampled data, it is recommended to have at least 3 consecutive proximate time points in each densely sampled region to allow the algorithm to detect contiguous temporal windows effectively [27].

Step 3: Data Preprocessing Address the specific challenges of longitudinal microbiome data [3]:

- Compositionality: Data are typically normalized so that sample sums equal a constant. The centered log-ratio (CLR) transformation is often applied before computing distances to mitigate compositionality effects [3].

- Zero-Inflation: A high proportion of zeros (70-90%) is common. Investigators should be aware that zeros can represent either true absence or technical limitations (below detection) [3].

- Overdispersion: The variance in count data often exceeds the mean. Modeling approaches like negative binomial distributions are more appropriate than Poisson models [3].

Model Execution and Rule Inference

Step 4: Generate Detector Pool MITRE automatically generates a comprehensive pool of potential "detectors" – conditional statements about bacterial abundances. These detectors are formulated for clades at all levels of the phylogenetic tree and across all possible time windows the data resolution allows [27]. Detectors take two primary forms:

- Average Abundance Detector: "Between times t0 and t1, the average abundance of bacterial group j is above/below threshold θ."

- Slope Detector: "Between times t0 and t1, the slope of the abundance of bacterial group j is above/below threshold θ."

Step 5: Bayesian Rule Learning The framework employs a Bayesian learning process to infer a posterior probability distribution over potential models [27]. The model consists of:

- A baseline probability of the default host status.

- A set of rules (possibly empty), where each rule is a conjunction of one or more detectors. Each rule has an associated multiplicative effect on the odds of the host outcome if all its conditions are met. The default prior favors parsimonious models (short, simple rule sets) and guards against overfitting by favoring the empty rule set (i.e., no association between microbiome and host status) unless evidence strongly suggests otherwise [27].

Step 6: Model Interpretation and Visualization Using the provided software and GUI, interpret the learned model. A simplified example rule might be [27]:

If, from month 2 to month 5, the average relative abundance of bacterial clade A is above 4.0%, AND from month 5 to month 8, the relative abundance of bacterial clade B increases by at least 1.0% per month, THEN the odds of disease increase by a factor of 10.

Diagram 1: MITRE Analysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Computational Tools for MITRE Analysis

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing Reagents | Provides cost-effective taxonomic profiling of microbial communities [28]. | Preferred for large-scale studies over shotgun metagenomics due to lower cost and complexity [28]. |

| Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing Reagents | Enables comprehensive functional profiling by sequencing all genetic material in a sample [29] [30]. | More costly but provides insights into microbial genes and pathways [30]. |

| MITRE Software Package | The primary open-source software for implementing the MITRE framework [27]. | Available at https://github.com/gerberlab/mitre/ [27]. |

| Phylogenetic Tree Reference | A tree detailing evolutionary relationships among microbial taxa, required by MITRE to group clades [27]. | |

| QIIME 2 or Similar Pipeline | For quantitative insights into microbial ecology; used for initial bioinformatic processing [28]. | Commonly used for generating OTU tables and calculating diversity measures from sequencing data. |

| R/Python with Specialized Packages | For data preprocessing, including handling compositionality (CLR), zero-inflation, and overdispersion [3]. | Packages like ZIBR, NBZIMM, or FZINBMM can address longitudinal data challenges [3]. |

| m-PEG5-nitrile | m-PEG5-nitrile|PEG-Based PROTAC Linker | m-PEG5-nitrile is a nitrile-terminated PEG linker used in PROTAC synthesis to enhance solubility. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| m-PEG7-Azide | m-PEG7-Azide, CAS 208987-04-6|PEG Linker for Click Chemistry |

Advanced Analysis: Visualizing Rule Structure and Data Flow