Microbiome Data Normalization: A Comprehensive Guide to Rarefaction, Filtering, and Advanced Methods for Robust Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive guide to normalization and filtering for 16S rRNA and shotgun metagenomic data, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Microbiome Data Normalization: A Comprehensive Guide to Rarefaction, Filtering, and Advanced Methods for Robust Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to normalization and filtering for 16S rRNA and shotgun metagenomic data, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational challenges of microbiome data, including compositionality, sparsity, and over-dispersion. The guide details established and emerging normalization methodologies, from rarefaction to model-based approaches like TaxaNorm and group-wise frameworks. It further addresses troubleshooting common pitfalls, optimizing workflows through filtering, and validating analyses via benchmarking and diversity metrics. The goal is to empower scientists with the knowledge to implement robust, reproducible preprocessing pipelines for accurate biological insight and therapeutic discovery.

The Unique Challenges of Microbiome Data: Why Normalization is Non-Negotiable

Microbiome data generated from 16S rRNA amplicon or shotgun metagenomic sequencing possess several unique statistical properties that complicate their analysis. Three core characteristics—compositionality, sparsity, and over-dispersion—fundamentally shape how researchers must approach data normalization, statistical testing, and biological interpretation. Compositionality refers to the constraint that microbial counts or proportions from each sample sum to a total (e.g., library size or 1), meaning they carry only relative rather than absolute abundance information [1] [2]. Sparsity describes the high percentage of zero values (often exceeding 90%) in the data, arising from both biological absence and technical limitations in detecting low-abundance taxa [3] [2]. Over-dispersion (heteroscedasticity) occurs when the variance in microbial counts exceeds what would be expected under simple statistical models like the Poisson distribution, often increasing with the mean abundance [4] [5]. Understanding these interconnected characteristics is essential for selecting appropriate analytical methods and avoiding misleading biological conclusions.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: How does data compositionality affect differential abundance analysis?

Answer: Compositionality introduces significant bias in differential abundance analysis (DAA) because changes in one taxon's abundance create apparent changes in all others, even when their absolute abundances remain unchanged.

- Underlying Issue: In a compositional dataset, all measurements are interdependent. An increase in the relative abundance of one taxon will mechanically cause a decrease in the relative abundance of others, potentially creating false positives [2] [6].

- Mathematical Evidence: Under a multinomial model, the observed log fold change ((\hat{\alpha}{1j})) for a taxon (j) converges to the true log fold change ((\beta{1j})) plus a bias term ((\Delta)) as sample size increases: (\hat{\alpha}{1j} \overset{p}{\rightarrow} \beta{1j} + \Delta). This bias term depends on the true abundances of all taxa in the ecosystem [6].

- Solution Strategy: Use DAA methods specifically designed to handle compositionality, such as ANCOM-BC, LinDA, or ALDEx2, rather than standard statistical tests applied to raw or simply normalized counts [2] [6].

FAQ 2: What are the best practices for handling sparse data with excess zeros?

Answer: Effective handling of sparse data involves filtering rare taxa and selecting robust analytical methods that do not assume normally distributed data.

- Underlying Issue: Excess zeros can be caused by biological absence, undersampling, or sequencing errors. This sparsity violates assumptions of many parametric models and can lead to overfitting in machine learning [3] [7].

- Solution Strategy - Filtering: A common and effective practice is to filter out taxa that appear in only a small percentage of samples or with very low counts. For example, filtering taxa present in less than 5-10% of samples has been shown to reduce technical variability while preserving biological signal and the performance of downstream machine learning models [3] [8].

- Solution Strategy - Modeling: For differential abundance analysis, methods like DESeq2 (adopted from RNA-seq) and negative binomial models can handle sparsity and over-dispersion better than traditional tests [3] [2]. For machine learning, tree-based models like Random Forest often perform well on relative abundance data, while linear models like logistic regression or SVM benefit from centered log-ratio (CLR) transformation [7].

FAQ 3: Why do my microbiome data show over-dispersion, and how can I model it?

Answer: Over-dispersion in microbiome data arises from both biological heterogeneity between subjects and technical variability. It can be addressed using specific statistical distributions and robust variance estimation techniques.

- Underlying Issue: The variance of a taxon's counts across samples is often much larger than its mean, a phenomenon known as over-dispersion. This invalidates the assumptions of a Poisson model, which requires the mean and variance to be equal [4] [5].

- Visual Diagnostic: A plot of squared residuals versus fitted values from a regression model will show a clear increasing trend, confirming heteroscedasticity [4].

- Solution Strategy - Model-Based:

- Negative Binomial Models: These are a direct extension of Poisson models that include an extra parameter to model the over-dispersion. They are implemented in tools like DESeq2 and edgeR [4] [2].

- Robust Covariance Estimation: A simpler yet effective approach is to use a Poisson log-linear model to estimate coefficients and then use robust methods (e.g., bootstrap or sandwich estimators) to calculate accurate standard errors that are valid even under model misspecification and over-dispersion [4].

Experimental Protocols for Characteristic-Specific Analysis

Protocol 1: Assessing and Correcting for Compositional Effects

Aim: To evaluate whether observed changes in taxon abundance are genuine or an artifact of compositionality.

Materials:

- Normalized OTU/ASV table

- Sample metadata with group labels

- R software with

ANCOMBC,LinDA, orALDEx2packages

Methodology:

- Data Input: Load your taxon count table and metadata.

- Run Compositional DAA: Apply a method designed for compositional data. For example, in

ANCOMBC, specify the model formula that includes your group variable of interest. - Interpret Results: Examine the output for differentially abundant taxa. The p-values and confidence intervals from these methods account for the compositional structure, reducing false discoveries.

- Validation: Compare the results with those from a standard method (e.g., Wilcoxon test on CLR-transformed data) to observe the differences in taxa identified as significant.

Protocol 2: A Filtering Workflow for Sparse Data

Aim: To reduce data sparsity by removing low-prevalence, likely spurious taxa prior to analysis.

Materials:

- Raw taxon count table

- R software with

phyloseqorgenefilterpackages

Methodology:

- Calculate Prevalence: For each taxon, compute the proportion of samples in which it is detected (count > 0).

- Set Threshold: Define a minimum prevalence threshold (e.g., 5%) and a minimum total abundance threshold (e.g., 10 counts across all samples) [3] [8].

- Apply Filter: Remove all taxa that do not meet both criteria from the count table.

- Downstream Analysis: Proceed with diversity analysis, ordination, or differential abundance testing on the filtered table. The reduced sparsity will lead to more stable and reliable results.

Data Presentation and Workflows

Table 1: Normalization and Analysis Method Selection Guide

Table: This table summarizes how different data characteristics favor specific methodological choices.

| Data Characteristic | Challenge | Recommended Normalization | Recommended Analysis Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compositionality | Spurious correlations; relative nature of data | Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) [7] [9] | ANCOM-BC, LinDA, ALDEx2 [2] [6] |

| Sparsity | Excess zeros; overfitting in machine learning | Presence/Absence; Filtering rare taxa [3] [7] | Random Forest; Negative Binomial models (DESeq2) [7] [2] |

| Over-Dispersion | Variance > mean; inflated false positives | Group-wise (G-RLE, FTSS) [6] | Negative Binomial models; Robust Poisson with sandwich SE [4] [2] |

Table 2: Key Software Reagents for Microbiome Data Analysis

Table: This table lists essential computational tools and their primary functions for addressing core data challenges.

| Research Reagent | Type | Primary Function | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| DESeq2 | R Package | Differential abundance testing using negative binomial models | [3] [2] |

| ANCOM-BC | R Package | Compositional differential abundance analysis with bias correction | [2] [6] |

| phyloseq | R Package | Data organization, filtering, and exploratory analysis | [3] |

| PERFect | R Package | Permutation-based filtering of rare taxa | [3] |

| SIAMCAT | R Package | Machine learning workflow for microbiome case-control studies | [8] |

| decontam | R Package | Contaminant identification based on DNA concentration or controls | [3] |

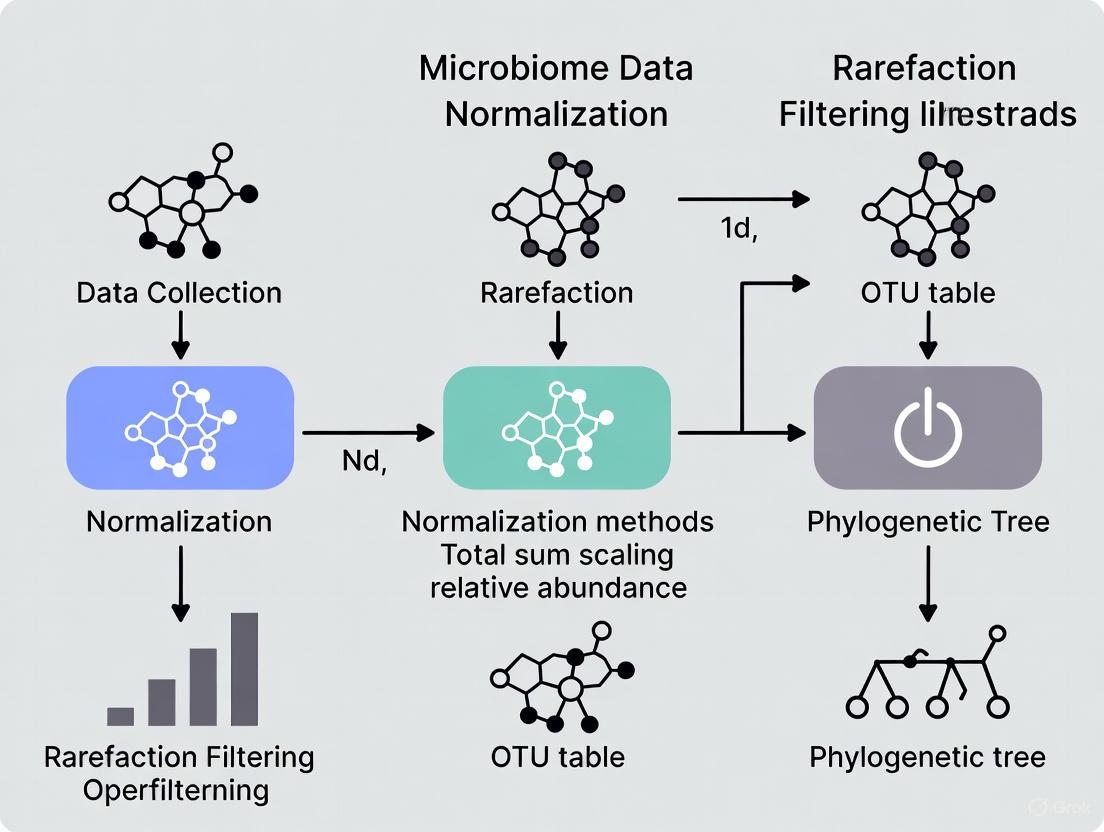

Visualization of Analytical Workflows

Diagram 1: Microbiome Data Analysis Decision Workflow

Microbiome Analysis Decision Workflow

Diagram 2: Impact and Solutions for Data Characteristics

Data Challenges and Solutions

Sequencing Depth Variation and Its Impact on Downstream Analysis

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is sequencing depth, and why does its variation pose a problem in microbiome studies?

Sequencing depth, also known as library size, refers to the total number of DNA sequence reads obtained for a single sample [2]. In microbiome studies, it is common to observe wide variation in sequencing depth across samples, sometimes by as much as 100-fold [10]. This variation is often technical, arising from differences in sample collection, DNA extraction, library preparation, and sequencing efficiency, rather than reflecting true biological differences [1] [2]. This poses a major challenge because common diversity metrics (alpha and beta diversity) and differential abundance tests are sensitive to these differences in sampling effort. If not controlled for, uneven sequencing depth can lead to inflated beta diversity estimates and spurious conclusions in statistical comparisons [10] [2].

2. What is the difference between rarefying and rarefaction?

While these terms are often used interchangeably, a key technical distinction exists:

- Rarefaction is a process that involves repeatedly subsampling a dataset (e.g., 100 or 1000 times) to a specific sequence depth and calculating the mean of the diversity metric over all subsamples. This provides a stable, robust estimate of what the diversity metric would be at a standardized sequencing depth [10].

- Rarefying typically refers to performing a single subsampling of each sample to a predefined depth without replacement [10] [11]. While it is widely used and often produces similar results to rarefaction, it can be more sensitive to the stochasticity of a single draw.

For alpha and beta diversity analysis, rarefaction is considered the more reliable approach [10] [11].

3. When should I use rarefaction, and what are its main limitations?

Rarefaction is particularly recommended for alpha and beta diversity analysis [10]. Simulation studies have shown it to be the most robust method for controlling for uneven sequencing effort in these contexts, providing the highest statistical power and acceptable false detection rates [10].

Its main limitations are:

- Data Removal: It discards valid data by subsampling, which can reduce statistical power for downstream analyses [2].

- Not for Differential Abundance: It is generally not recommended for differential abundance testing (DAA), as other methods have been specifically developed to handle the compositional nature of the data for this purpose [2] [11].

4. What normalization methods should I use for differential abundance analysis (DAA)?

For DAA, the choice is more complex due to the compositional nature of microbiome data. No single method is universally best, and the choice often depends on your data's characteristics [2]. The table below summarizes some key approaches.

Table 1: Common Normalization and Differential Abundance Methods for Microbiome Data

| Method Category | Example Methods | Brief Description | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compositional Data Analysis | ANCOM-BC [6], ALDEx2 [6] | Uses statistical de-biasing to correct for compositionality without external normalization. | ANCOM-BC has been shown to have good control of the false discovery rate (FDR) [2]. |

| Normalization-Based | DESeq2 [2], edgeR [6], MetagenomeSeq [6] | Relies on an external normalization factor to scale counts before testing. | Performance can suffer with large compositional bias or high variance; new group-wise methods like G-RLE and FTSS show improved FDR control [6]. |

| Center Log-Ratio (CLR) | CLR Transformation [7] | Applies a log-ratio transformation to address compositionality. | Requires dealing with zeros (e.g., using pseudocounts), which can influence results [2]. |

5. How does sequencing depth interact with other experimental choices, like PCR replication?

Both sequencing depth and the number of PCR replicates influence the recovery of microbial taxa, particularly low-abundance (rare) taxa [12]. Higher sequencing depth increases the probability of detecting rare taxa within a single PCR replicate. Conversely, performing more PCR replicates from the same DNA extract also increases the chance of detecting rare taxa that might be stochastically amplified. Studies suggest that for complex communities, species accumulation curves may only begin to plateau after 10-20 PCR replicates [12]. Therefore, for a comprehensive survey of diversity, a balanced approach with sufficient sequencing depth and PCR replication is ideal.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Inflated Beta Diversity Linked to Sequencing Depth

Problem: A PCoA plot shows clear separation between sample groups, but you suspect it is driven by differences in their average sequencing depths rather than true biological differences.

Solution Steps:

- Confirm the Suspicions: Create a boxplot of the library sizes (total reads per sample) grouped by your condition of interest. If the median depths are significantly different (e.g., by an order of magnitude), your beta diversity results are likely confounded [2].

- Apply Rarefaction: For standard beta diversity metrics like Bray-Curtis or Jaccard dissimilarity, apply rarefaction to normalize the sequencing depth across all samples [10].

- Re-run Analysis: Generate a new PCoA plot using the rarefied data. A true biological signal should persist, while a technically driven signal will diminish.

- Alternative Approach (for some metrics): If using Aitchison distance (based on CLR transformation), ensure that the data does not have extreme compositional bias, as this can sometimes break down the method's ability to control for sequencing depth [10].

Issue: Choosing a Normalization Method for Differential Abundance

Problem: You are unsure which normalization or differential abundance method to use for your specific dataset, which has highly uneven library sizes and is sparse (many zeros).

Solution Steps:

- Profile Your Data: Calculate key data characteristics: the range of library sizes, the proportion of zeros in your feature table, and the effect size you expect between groups.

- Select a Strategy: Refer to Table 1. Given the challenges, a two-pronged approach is often wise:

- For Robustness: Use a compositional data analysis method like ANCOM-BC or LinDA, which are designed to handle compositionality and sparsity without relying on a single normalization factor [6].

- For Comparison: Also, try a normalization-based method that is robust to your data characteristics. If you have large group-wise differences, consider newer methods like FTSS with MetagenomeSeq [6].

- Benchmark and Compare: Run your analysis through both pipelines. Compare the lists of significant taxa. Taxa that are identified by multiple, methodologically distinct approaches are more likely to be robust biological signals.

Workflow: Decision Process for Handling Sequencing Depth

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for choosing an appropriate method based on your analytical goal.

Essential Alpha Diversity Metrics and Their Interpretation

Alpha diversity metrics provide different insights into the within-sample diversity. It is recommended to use a suite of metrics to get a comprehensive picture. The table below summarizes key metrics based on a large-scale analysis of human microbiome data [13].

Table 2: Key Categories of Alpha Diversity Metrics and Their Interpretation

| Metric Category | Key Aspect Measured | Representative Metrics | Practical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Richness | Number of distinct taxa | Chao1, ACE, Observed ASVs | Increases with the total number of observed Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs). High value = many unique taxa. |

| Dominance/Evenness | Distribution of abundances | Berger-Parker, Simpson, ENSPIE | Berger-Parker is the proportion of the most abundant taxon. Low evenness = a community dominated by few taxa. |

| Phylogenetic | Evolutionary relatedness of taxa | Faith's Phylogenetic Diversity (PD) | Depends on both the number of ASVs and their phylogenetic branching. High value = phylogenetically diverse community. |

| Information | Combination of richness and evenness | Shannon, Pielou's Evenness | Shannon increases with more ASVs and decreases with imbalance. Pielou's is Shannon evenness. |

Note: The value of most richness metrics is strongly determined by the total number of observed ASVs. It is recommended to report metrics from all four categories to characterize a microbial community fully [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for Microbiome Data Normalization

| Item / Software Package | Function / Purpose | Key Features / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| QIIME 2 [11] | A comprehensive, plugin-based microbiome bioinformatics platform. | Includes tools for rarefaction, alpha/beta diversity analysis, and integrates with various normalization methods. |

| R/Bioconductor | A programming environment for statistical computing. | The primary platform for most differential abundance and advanced normalization packages (e.g., DESeq2, MetagenomeSeq, ANCOM-BC, phyloseq). |

| vegan R Package [10] | A community ecology package for multivariate analysis. | Contains the rrarefy() and avgdist() functions for rarefying and rarefaction, respectively. |

| DESeq2 [2] [6] | A method for differential abundance analysis based on negative binomial models. | Adopted from RNA-seq; can be powerful but may have inflated FDR with very uneven library sizes and strong compositionality [2]. |

| MetagenomeSeq [6] | A method for DAA that uses a zero-inflated Gaussian model. | Often used with its built-in Cumulative Sum Scaling (CSS) normalization, but can be combined with newer methods like FTSS [6]. |

| ANCOM-BC [6] | A compositional method for DAA that corrects for bias. | Does not require external normalization; known for good control of the False Discovery Rate (FDR) [2] [6]. |

| q2-boots (QIIME 2 Plugin) [11] | A plugin for performing rarefaction. | Implements the preferred rarefaction approach over a single rarefying step, providing more stable diversity estimates. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is compositional bias, and why does it lead to spurious associations?

Compositional bias is a fundamental property of sequencing data where the measured abundance of any feature (e.g., a bacterial taxon) only carries information relative to other features in the same sample, not its absolute abundance [14]. This occurs because sequencing technologies output a fixed number of reads per sample; thus, the data represent proportions that sum to a constant (e.g., 1 or the total read count) [7] [14].

This compositionality leads to spurious associations because an increase in one taxon's abundance will cause the observed relative abundances of all other taxa to decrease, even if their absolute abundances remain unchanged [14] [15]. In Differential Abundance Analysis (DAA), this can make truly non-differential taxa appear to be differentially abundant, thereby inflating false discovery rates (FDR) [6].

Q2: Our lab is new to microbiome analysis. Which normalization method should we start with?

For researchers beginning microbiome DAA, Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) transformation is a robust starting point. Evidence shows that CLR normalization improves the performance of classifiers like logistic regression and support vector machines and facilitates effective feature selection [7]. It is also a core transformation used by well-established tools like ALDEx2 [16] [14].

However, the "best" method can depend on your specific data and research goal. The table below summarizes the performance of common normalization methods based on recent benchmarks.

| Normalization Method | Key Principle | Best Suited For | Considerations & Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) [7] [16] | Log-transforms counts after dividing by the geometric mean of the sample. | ALDEx2, logistic regression, SVM [7]. |

Handles compositionality well; beware of zeros requiring pre-processing [15]. |

| Group-Wise (G-RLE, FTSS) [6] | Calculates normalization factors using group-level summary statistics. | Scenarios with large inter-group variation; used with MetagenomeSeq/DESeq2/edgeR. |

Recent methods showing higher power and better FDR control in challenging settings [6]. |

| Rarefaction [17] | Subsampling reads without replacement to a uniform depth. | Alpha and beta diversity analysis prior to phylogenetic methods. | Common but debated; can discard data; use if library sizes vary greatly (>10x) [17]. |

| Relative Abundance | Simple conversion to proportions. | Random Forest models [7]. | Simple but does not address compositionality for many statistical tests. |

| Presence-Absence | Converts abundance data to binary (1/0) indicators. | All classifiers when abundance information is less critical [7]. | Achieves performance similar to abundance-based transformations in some classifications [7]. |

Q3: We applied a standard RNA-Seq tool to our microbiome data and got strange results. Why?

This is a common pitfall. Methods designed for RNA-Seq (like the standard DESeq2 or edgeR workflows) often rely on assumptions that do not hold for microbiome data [14]. Specifically, they may assume that most features are not differentially abundant, an assumption frequently violated in microbial communities where a large fraction of taxa can change between conditions [6] [15].

Furthermore, microbiome data are typically much sparser (contain more zeros) than transcriptomic data, which can cause these methods to fail or produce biased results [15]. It is recommended to use tools specifically designed for or validated on microbiome data, such as ALDEx2, ANCOM-BC, MaAsLin3, LinDA, or ZicoSeq [16].

Q4: How should we handle the excessive zeros in our dataset before DAA?

The extensive zeros in microbiome data can be technical artifacts (from low sequencing depth) or biological (true absence of a taxon) [3]. The optimal handling strategy depends on the nature of your zeros.

- Filtering: Apply prevalence-based filtering to remove rare taxa observed in only a small fraction of samples. This reduces data sparsity, mitigates technical variability, and helps control for multiple testing without significantly compromising the ability to find truly discriminatory taxa [16] [3]. A common filter is to keep features present in at least 10% of samples [16].

- Zero Imputation: Some DAA methods, like

ALDEx2andMaAsLin3, incorporate Bayesian or pseudo-count strategies to impute zeros [16]. - Specialized Models: Other methods, such as

metagenomeSeq, use zero-inflated mixture models designed to account for the excess zeros directly [16].

The decision flow below outlines a general pre-processing workflow for DAA, incorporating filtering and normalization.

Q5: Which differential abundance methods best control for false discoveries?

Based on recent benchmarking studies, no single method is universally superior, but some consistently perform well. It is highly recommended to run multiple DAA methods to see if the findings are consistent across different approaches [16].

The following table lists several robust methods recommended in recent literature.

| DAA Tool | Statistical Approach | How It Addresses Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| ALDEx2 [16] | Dirichlet Monte-Carlo samples + CLR + Welch's t-test/Wilcoxon | Models technical variation within samples; addresses compositionality via CLR. |

| ANCOM-BC [16] [6] | Linear model with bias correction | Estimates and corrects for unknown sampling fractions to control FDR. |

| MaAsLin3 [16] | Generalized linear models | Handles zeros with a pseudo-count strategy; allows for complex covariate structures. |

| LinDA [16] | Linear models | Specifically designed for power and robustness in sparse, compositional data. |

| ZicoSeq [16] | Mixed model with permutation test | Recommended for its performance in benchmark evaluations [16]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Protocol 1: Performing Differential Abundance Analysis with ALDEx2

This protocol is adapted from the Orchestrating Microbiome Analysis guide and is a strong choice for consistent results [16].

Data Preparation and Pre-processing:

- Agglomerate your data to a specific taxonomic rank (e.g., Genus) to reduce feature space.

- Filter features based on a prevalence threshold (e.g., 10%) to remove rare taxa.

- Optional: Transform counts to relative abundances.

ALDEx2performs its own internal transformation, but this step can be part of a standardized workflow [16].

Run ALDEx2:

Interpret Results:

- Identify significantly differentially abundant taxa based on a corrected p-value (e.g., Benjamini-Hochberg) and an effect size threshold.

- Use

aldex.plotto create an MA or MW plot to visualize the relationship between abundance, dispersion, and differential abundance.

Protocol 2: A Robust DAA Workflow Using Multiple Methods

To ensure robust and replicable findings, employ a multi-method workflow as illustrated below.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Tool / Resource | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| QIIME 2 [17] | An end-to-end pipeline for microbiome analysis from raw sequences to diversity analysis and DAA. | Processing 16S rRNA sequence data, generating feature tables, and core diversity metrics. |

| R/Bioconductor | The primary platform for statistical analysis of microbiome data, hosting hundreds of specialized packages. | Performing custom DAA, normalization, and visualization (e.g., with phyloseq, mia) [18] [16]. |

| ALDEx2 R Package [16] [14] | A DAA tool that uses a Dirichlet-multinomial model and CLR transformation to account for compositionality. | Identifying differentially abundant features in case-control studies while controlling for spurious correlations. |

| PERFect R Package [3] | A principled filtering method to remove spurious taxa based on the idea of loss of power. | Systematically reducing the feature space by removing contaminants and noise prior to DAA. |

| Decontam R Package [3] | Identifies potential contaminant sequences using DNA concentration and/or negative control samples. | Removing known laboratory and reagent contaminants from the feature table. |

| MicrobiomeHD Database [7] | A curated database of standardized human gut 16S microbiome case-control studies. | Benchmarking new DAA methods or normalization approaches against a large collection of real datasets. |

In microbiome research, distinguishing between technical and biological variation is a fundamental goal of data normalization. Technical variation arises from the measurement process itself, including sequencing depth, protocol differences, and reagent batches. In contrast, biological variation reflects true differences in microbial community composition between samples or individuals. Normalization techniques are designed to minimize the impact of technical noise, thereby allowing researchers to accurately discern meaningful biological signals [19].

The following guide provides troubleshooting advice and foundational knowledge to help you select and implement the correct normalization strategy for your specific research context.

Normalization Methods at a Glance

The table below summarizes common normalization methods and their primary applications for addressing different types of variation.

| Normalization Method | Primary Goal | Key Application / Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) | Mitigate technical variation from compositionality | Improves performance of logistic regression and SVM models; handles compositional nature of microbiome data [7] [20]. |

| Presence-Absence (PA) | Reduce impact of technical variation from sequencing depth | Converts abundance data to binary (0/1) values; achieves performance similar to abundance-based methods while mitigating depth effects [7]. |

| Rarefaction & Filtering | Mitigate technical variation from sampling depth & sparsity | Reduces data sparsity and technical variability, improving reproducibility and the robustness of downstream analysis [3]. |

| Parametric Normalization | Correct for technical variation using known controls | Uses a parametric model based on control samples to fit normalization coefficients and test for linearity in probe responses [21]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My machine learning model for disease classification is not generalizing well. Could technical noise be the issue, and which normalization should I try?

A: High dimensionality and technical sparsity in microbiome data often cause overfitting. A robust normalization and feature selection pipeline can massively reduce the feature space and improve model focus.

- Recommended Action: Apply Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) normalization, which has been shown to improve the performance of models like logistic regression and support vector machines. Following this, use a feature selection method such as minimum Redundancy Maximum Relevancy (mRMR) or LASSO to identify a compact, robust set of microbial features for classification [7].

Q2: How do I decide whether a rare taxon in my data is a true biological signal or a technical artifact?

A: This is a common challenge due to the high sparsity of microbiome data, where many rare taxa can be sequencing artifacts or contaminants.

- Recommended Action: Implement a filtering step to remove rare taxa present in only a small number of samples or with very low counts. This reduces technical variability and data complexity while preserving the integrity of the biological signal for downstream diversity and differential abundance analysis [3].

Q3: What is the core difference between using technical replicates and biological replicates in the context of normalization?

A: These replicates answer fundamentally different questions and should be used together.

- Technical Replicates: These are repeated measurements of the same sample. They are essential for assessing the reproducibility of your assay or technique and help quantify the level of technical variation in your pipeline. They do not provide information about biological relevance [19].

- Biological Replicates: These are measurements from biologically distinct samples (e.g., different individuals, separately cultured cells). They are necessary to capture random biological variation and to determine if an experimental effect can be generalized beyond a single sample [19].

Q4: When integrating microbiome data with another omics layer, like metabolomics, how do I handle normalization?

A: Integration requires careful, coordinated normalization to ensure meaningful results.

- Recommended Action: Account for the specific properties of each data type. For microbiome data, use transformations like CLR or Isometric Log-Ratio (ILR) to handle its compositional nature before integration. Benchmarking studies suggest evaluating multiple integrative methods (e.g., sCCA, sPLS) to find the best approach for your specific research question, whether it's inferring global associations or identifying individual microbe-metabolite relationships [20].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High false positive rates in differential abundance analysis. | Technical variation (e.g., differing library sizes) is being misinterpreted as biological signal. | Apply CLR transformation to properly handle compositional data and reduce spurious correlations [20]. |

| Poor performance of a predictive model on a new dataset. | Model is overfitting to technical noise in the training data rather than robust biological features. | Implement a feature selection method (e.g., mRMR, LASSO) after normalization to identify a stable, compact set of discriminatory features [7]. |

| Inconsistent diversity measures (alpha/beta diversity) across batches. | Strong batch effects or contamination from the sequencing process. | Use rarefaction and filtering to alleviate technical variability between labs or runs. For known contaminants, use specialized tools like the decontam R package in conjunction with filtering [3]. |

| Weak or no association found between matched microbiome and metabolome profiles. | Technical variation in either dataset is obscuring true biological associations. | Prior to integration, normalize each dataset appropriately (e.g., CLR for microbiome, log transformation for metabolomics) and use multivariate association methods (e.g., Procrustes, Mantel test) designed for this purpose [20]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials

| Item / Solution | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Hoechst Dye | A fluorescent dye compatible with the DAPI filter set, used for staining and counting cell nuclei in normalization protocols for functional assays (e.g., Seahorse XF analyses) [22]. |

| Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) Transformation | A mathematical transformation applied to microbiome abundance data to account for its compositional nature, mitigating technical variation and improving downstream statistical analysis [7] [20]. |

| Live Biotherapeutic Products (LBPs) | Defined consortia of viable microbes used as prescription therapeutics to modify the human microbiome for treating conditions like recurrent C. difficile infection [23]. |

| Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) | The transfer of processed donor stool into a patient to restore a healthy gut microbial community; a therapeutic intervention and a source of material for microbiome research [23]. |

| LASSO / mRMR Feature Selection | Computational methods used after normalization to identify the most relevant and non-redundant microbial features, improving model interpretability and robustness against overfitting [7]. |

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating a Normalization Strategy

This protocol outlines a general approach for benchmarking normalization methods in a microbiome analysis pipeline.

1. Define a Biological Question: Start with a clear objective (e.g., "Identify taxa differentiating disease from healthy controls").

2. Apply Normalization Methods: Process your raw count data using different methods: - CLR Transformation - Rarefaction to an even sequencing depth - Presence-Absence transformation - Filtering of low-prevalence taxa

3. Conduct Downstream Analysis: Perform the core analysis for each normalized dataset. This typically involves: - Beta-diversity analysis (e.g., using PCoA) - Differential abundance testing (e.g., with DESeq2 or LEfSe) - Machine learning for classification (e.g., using Random Forest)

4. Benchmark Performance: Evaluate the results from each normalized dataset based on: - Model Accuracy: Area Under the Curve (AUC) for classifiers. - Biological Interpretability: Consistency of identified taxa with known biology. - Robustness and Reproducibility: Ability to produce stable results across different subsets of data or in independent datasets [7] [20] [3].

The logical workflow for this benchmarking experiment is summarized in the diagram below:

A Practical Toolkit: From Established Normalization to Emerging Methods

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the primary purpose of normalizing microbiome data? Microbiome data normalization is essential to account for significant technical variations, particularly differences in sequencing depth between samples. This process ensures that samples are comparable and that downstream analyses (like beta-diversity or differential abundance testing) are robust and biologically meaningful, rather than skewed by artifactual biases from library preparation or sequencing [24] [2].

2. When should I use TSS, CSS, or TMM? The choice depends on your data characteristics and analytical goals. The table below summarizes the core properties and best-use cases for each method.

Table 1: Comparison of TSS, CSS, and TMM Normalization Methods

| Method | Full Name | Core Procedure | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| TSS | Total Sum Scaling | Divides each sample's counts by its total library size, converting them to proportions that sum to 1 [24] [25]. | - A simple, intuitive baseline method [24].- Data visualization (e.g., bar plots) [25]. |

| CSS | Cumulative Sum Scaling | Scales counts based on a cumulative sum up to a data-driven percentile, which is more robust to the high variability of microbiome data than the total sum [24]. | - Mitigating the influence of highly variable taxa [24].- An alternative to rarefaction for some downstream analyses. |

| TMM | Trimmed Mean of M-values | Calculates a scaling factor as a weighted trimmed mean of the log-expression ratios between samples, effectively identifying a stable set of features for comparison [24]. | - Datasets with large variations in library sizes [9] [2].- Cross-study predictions where performance needs to be consistent [9]. |

3. My data has very different library sizes (over 10x difference). Which method is most suitable? For library sizes varying over an order of magnitude, rarefying is often recommended as an initial step, especially for 16S rRNA data [25] [26]. Following rarefaction, or if you prefer not to rarefy, TMM has been shown to demonstrate more consistent performance compared to TSS-based methods when there are large differences in average library size, as it is less sensitive to these extreme variations [9] [2].

4. How do these methods perform in predictive modeling, such as disease phenotype prediction? Performance can vary based on the heterogeneity of the datasets. A 2024 study evaluating cross-study phenotype prediction found that scaling methods like TMM show consistent performance. In contrast, some compositional data analysis methods exhibited mixed results. For the most challenging scenarios with significant heterogeneity between training and testing datasets, more advanced transformation or batch correction methods may be required [9].

5. Are there any major limitations or pitfalls I should be aware of? Yes, each method has its considerations:

- TSS: As a compositional method, it is highly sensitive to the presence of highly abundant taxa, which can skew the entire profile [24] [2].

- CSS: Its performance can be mixed in some predictive modeling contexts, and it may not fully address all compositional effects [9].

- TMM: This method was originally designed for RNA-seq data and assumes that most features are not differentially abundant, an assumption that may not always hold true in microbiome contexts [1].

Troubleshooting Guide

Table 2: Common Issues and Solutions for Scaling Normalization Methods

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Poor clustering in ordination plots (e.g., PCoA) | Normalization method failed to adequately account for large differences in library sizes or compositionality [2]. | 1. Check library sizes; if they vary by >10x, apply rarefaction first [25] [26].2. Switch from TSS to a more robust method like CSS or TMM [24] [9]. |

| High false discovery rate in differential abundance testing | The normalization method is not controlling for compositionality effects or library size differences, leading to spurious findings [2]. | 1. Avoid using TSS alone for differential abundance analysis.2. Use methods specifically designed for compositional data or employ tools like DESeq2 or ANCOM that have built-in normalization procedures for differential testing [25] [2] [27]. |

| Low prediction accuracy in cross-study models | The normalization method did not effectively reduce the technical heterogeneity (batch effects, different background distributions) between the training and testing datasets [9]. | 1. Consider using TMM, which has shown more consistent cross-study performance [9].2. Explore batch correction methods (e.g., BMC, Limma) if the primary issue is known batch effects [9]. |

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating Normalization Methods

Objective: To compare the performance of TSS, CSS, and TMM normalization methods on a given microbiome dataset for downstream beta-diversity analysis.

Materials and Reagents:

- Software: R environment.

- Key R Packages:

phyloseqfor data handling,veganfor diversity calculations,MicrobiomeStat(or similar) for applying CSS and TMM. - Input Data: A phyloseq object containing an OTU/ASV table (raw counts) and sample metadata.

Methodology:

- Data Pre-processing: Begin by filtering your raw feature table to remove low-abundance OTUs/ASVs that are likely noise. A common threshold is to keep features that have at least 2 counts in at least 11% of the samples [26].

- Apply Normalizations: Generate three different normalized datasets.

- For TSS (Proportions):

- For CSS (using

MicrobiomeStat): - For TMM (using

MicrobiomeStat):

- Downstream Analysis & Evaluation: Calculate beta-diversity distances (e.g., Bray-Curtis) on each normalized dataset and perform ordination (PCoA).

- Interpret Results: Compare the PCoA plots. A good normalization method will lead to clear clustering of samples by biological groups (e.g., disease state) rather than by technical artifacts like library size. The effectiveness can be assessed visually and statistically (e.g., using PERMANOVA) to see which method best separates the groups of interest.

Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for selecting and applying these normalization methods within a typical microbiome analysis pipeline.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Microbiome Normalization Analysis

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Normalization |

|---|---|---|

| R Programming Language | Software Environment | The primary platform for statistical computing and implementing almost all normalization methods [24] [26]. |

| phyloseq (R Package) | R Package | A cornerstone tool for managing, filtering, and applying basic normalizations (like TSS) to microbiome data [26]. |

| MicrobiomeStat (R Package) | R Package | Provides a unified function (mStat_normalize_data) to apply various methods, including CSS, TMM, and others, directly to a microbiome data object [24]. |

| vegan (R Package) | R Package | Used for calculating ecological distances (e.g., Bray-Curtis) and performing ordination (PCoA) to evaluate the effectiveness of normalization [26]. |

| curatedMetagenomicData | Data Resource | A curated collection of real human microbiome datasets; useful for benchmarking normalization methods against standardized data [28]. |

Definitions and Key Concepts

What is the difference between rarefying and rarefaction?

The terms "rarefying" and "rarefaction" are often used interchangeably, but they refer to distinct procedures in microbiome data analysis.

Rarefying is a single random subsampling of sequences from each sample to a predetermined, even sequencing depth. This approach discards a portion of the data and provides only a single snapshot of the community structure at that sequencing depth [29] [10].

Rarefaction is a statistical technique that repeats the subsampling process many times (e.g., 100 or 1,000 iterations) and calculates the mean of diversity metrics across all iterations. This approach incorporates all observed data to estimate what the diversity metrics would have been if all samples had been sequenced to the same depth [10].

Table: Comparison of Rarefying vs. Rarefaction

| Feature | Rarefying | Rarefaction |

|---|---|---|

| Procedure | Single random subsampling to even depth | Repeated subsampling many times |

| Data Usage | Discards unused sequences permanently | Incorporates all data through repeated trials |

| Output | Single estimate of diversity | Average diversity metric across iterations |

| Implementation | rrarefy in vegan, sub.sample in mothur |

rarefy or avgdist in vegan, summary.single in mothur |

| Stability | Provides a single snapshot, more variable | More stable estimates through averaging |

The Rarefaction Protocol: A Step-by-Step Guide

Standard Rarefaction Procedure

The standard rarefaction protocol consists of the following steps [30] [29]:

Select a minimum library size (rarefaction level): Choose a normalized sequencing depth, typically based on the smallest library size among adequate samples.

Discard inadequate samples: Remove samples with fewer sequences than the selected minimum library size from the analysis.

Subsample remaining libraries: Randomly select sequences without replacement until all libraries have the same size.

Calculate diversity metrics: Use the normalized data to compute alpha or beta diversity measures.

Repeat and average (for rarefaction): For proper rarefaction, repeat steps 3-4 many times and calculate average diversity metrics.

Experimental Protocol for Repeated Rarefaction

For more robust results, the following detailed protocol for repeated rarefaction is recommended [29]:

Title: Repeated Rarefaction Workflow

Materials and Reagents:

- High-quality 16S rRNA gene sequence data

- Bioinformatic pipeline (QIIME2, mothur, or phyloseq)

- Computing resources for multiple iterations

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Organize sequence data into a feature table (OTU or ASV table)

- Threshold Selection: Identify the minimum acceptable sequencing depth based on your data

- Sample Filtering: Remove samples with sequences below the threshold

- Iterative Subsampling: Perform 100-1,000 iterations of random subsampling

- Metric Calculation: For each iteration, calculate desired diversity metrics

- Result Aggregation: Compute mean values for each diversity metric across all iterations

The Scientific Debate: Evidence and Counterevidence

Arguments Against Rarefying

The primary criticisms of rarefying were articulated in McMurdie and Holmes's influential 2014 paper [30]:

- Statistical Inadmissibility: Discarding valid data is statistically inadmissible

- Reduced Power: Can reduce statistical power to detect differentially abundant taxa

- False Positives: May increase false positive rates in differential abundance testing

- Sample Loss: Requires discarding entire samples below the threshold

- Arbitrary Threshold: Choice of rarefaction level can be subjective

Evidence Supporting Rarefaction

Recent research has challenged these criticisms and provided support for rarefaction [10] [31]:

- Confusion of Terms: The original critique conflated rarefying (single subsample) with rarefaction (multiple iterations)

- Robust Performance: Rarefaction effectively controls for uneven sequencing effort in diversity analyses

- Experimental Design Issues: Problems with the original simulation design penalized rarefaction unfairly

- Superior Performance: Rarefaction maintains higher statistical power and better false discovery rate control compared to alternatives, particularly when sequencing depth is confounded with treatment groups

Table: Performance Comparison of Normalization Methods

| Method | Alpha Diversity | Beta Diversity | Differential Abundance | Data Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rarefaction | Excellent [10] | Excellent [10] | Poor [30] | Count-based |

| CLR | Variable [7] | Good [9] | Good [1] | Compositional |

| DESeq2 | Not applicable | Not applicable | Good [30] | Count-based |

| edgeR | Not applicable | Not applicable | Good [30] | Count-based |

| Proportions | Poor [30] | Poor [30] | Poor [30] | Compositional |

| TMM | Variable [9] | Variable [9] | Good [9] | Count-based |

Troubleshooting Guide

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: How do I choose the appropriate rarefaction depth? A: The rarefaction depth should be based on your smallest high-quality sample. Examine the library size distribution and consider the trade-off between including more samples versus retaining more sequences per sample. Visualization of rarefaction curves can help determine where diversity plateaus [29].

Q: What should I do if too many samples are below my desired rarefaction threshold? A: If excessive sample loss occurs, consider either: (1) selecting a lower rarefaction depth that retains more samples, or (2) using alternative normalization methods like CENTER or variance-stabilizing transformations for specific analyses [1] [9].

Q: Is rarefaction appropriate for differential abundance analysis? A: No, most evidence suggests rarefaction is not ideal for differential abundance testing. For this specific application, methods designed for count data like DESeq2, edgeR, or metagenomeSeq are generally more appropriate [30] [6].

Q: How many iterations should I use for repeated rarefaction? A: Most studies use 100-1,000 iterations. The law of diminishing returns applies, with stability generally achieved by 100 iterations, but more iterations provide more precise estimates [29].

Q: Can I combine rarefaction with other normalization methods? A: Yes, some workflows apply rarefaction followed by CENTER transformation. However, the benefits of this approach depend on your specific analytical goals and should be validated for your dataset [11].

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Rarefaction Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| QIIME2 | End-to-end microbiome analysis pipeline | q2-feature-table rarefy |

| mothur | 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis | sub.sample (rarefying), summary.single (rarefaction) |

| vegan R package | Ecological diversity analysis | rrarefy() (rarefying), rarefy() (rarefaction) |

| phyloseq R package | Microbiome data analysis and visualization | rarefy_even_depth() |

| iNEXT | Interpolation and extrapolation of diversity | Rarefaction-extrapolation curves |

Decision Framework and Best Practices

Title: Normalization Method Decision Guide

Current Consensus and Recommendations

Based on the current evidence [10] [9] [31]:

- For diversity analyses: Rarefaction remains a robust, defensible approach for controlling uneven sequencing effort

- For differential abundance: Methods like DESeq2, edgeR, or metagenomeSeq are more appropriate

- For machine learning: Multiple approaches should be tested, with CENTER and batch correction methods often performing well

- Implementation matters: Repeated rarefaction (true rarefaction) outperforms single subsampling (rarefying)

- Context dependence: The optimal method depends on your specific research question, data characteristics, and analytical goals

The practice of rarefaction continues to evolve, with ongoing research refining best practices for microbiome data normalization. By understanding both its historical context and current evidence, researchers can make informed decisions about when and how to apply rarefaction in their experimental workflows.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why should I use un-normalized counts as input for DESeq2, and how does it handle library size differences internally?

DESeq2 requires un-normalized counts because its statistical model relies on the raw count data to accurately assess measurement precision. Using pre-normalized data like counts scaled by library size violates the model's assumptions. DESeq2 internally corrects for library size differences by incorporating size factors into its model. These factors account for variations in sequencing depth, allowing for valid comparisons between samples [32].

Q2: What are the key challenges in microbiome differential abundance analysis that tools like MetagenomeSeq aim to address?

Microbiome data presents several unique challenges that complicate differential abundance analysis:

- Compositionality: Data represents relative proportions, not absolute abundances. A change in one taxon's abundance can spuriously affect the perceived abundances of all others [33] [2].

- Sparsity: Data contains a high proportion of zeros (often ~90%), which can arise from biological absence or undersampling [33] [1] [2].

- High Dimensionality: There are typically far more taxa (variables) than samples [33] [1].

- Over-dispersion: Variance in the data often exceeds what standard models expect [1]. Tools like MetagenomeSeq are specifically designed with these challenges in mind, for instance, by using a zero-inflated model to handle sparsity [33].

Q3: My data comes from a longitudinal study. Which model is more appropriate for handling within-subject correlations: GEE or GLMM?

For analyzing longitudinal microbiome data, the Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) model is often a suitable choice. GEE is particularly robust for handling within-subject correlations as it estimates population-average effects and remains consistent even if the correlation structure is slightly misspecified. In contrast, Generalized Linear Mixed Models (GLMMs) are computationally more challenging for non-normal data and provide subject-specific interpretations. GEE offers a flexible approach for correlated data without the complexity of numerical integration required by GLMMs [33] [34].

Q4: What is the difference between a normalization method and a data transformation?

This is a critical distinction in data preprocessing:

- Normalization primarily aims to account for technical variations, such as differences in sequencing depth between samples, to make them comparable. Examples include Total Sum Scaling (TSS) and Cumulative Sum Scaling (CSS) [35] [24].

- Transformation applies a mathematical function to the data to change its structure, often to meet the assumptions of statistical tests (e.g., achieving normality, stabilizing variance). A common transformation in microbiome analysis is the Centered Log-Ratio (CLR), which helps address compositionality [35]. Many analysis pipelines involve both steps.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor False Discovery Rate (FDR) Control with DESeq2 or MetagenomeSeq

Problem: Your analysis identifies many differentially abundant taxa, but a high proportion are likely false positives.

Solutions:

- Consider an Alternative Normalization-Transformation Combination: If using a tool like DESeq2, ensure you are providing raw counts. For microbiome data, a framework that integrates Counts adjusted with Trimmed Mean of M-values (CTF) normalization with a Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) transformation has been shown to improve FDR control compared to some default methods in other tools [33] [34].

- Evaluate Group-Wise Normalization: Recent developments suggest that normalization should be conceptualized as a group-level task rather than a sample-level one. Methods like Group-Wise Relative Log Expression (G-RLE) or Fold-Truncated Sum Scaling (FTSS) can reduce bias and improve FDR control in challenging scenarios where group differences are large [36].

- Try a Compositional Method: If compositional effects are a primary concern, consider using a method designed explicitly for this, such as ANCOM or ALDEx2, which have demonstrated better FDR control in some benchmarking studies [33] [2].

Issue 2: Handling Excess Zeros in MetagenomeSeq

Problem: The Zero-Inflated Gaussian (ZIG) model in MetagenomeSeq fails to converge or provides unrealistic results.

Solutions:

- Check Data Sparsity: Excessively sparse data (e.g., >95% zeros) can be problematic. Consider filtering out very low-abundance taxa that are absent in most samples before analysis to improve model performance.

- Verify Normalization: MetagenomeSeq uses Cumulative Sum Scaling (CSS) normalization to account for sampling zeros. Ensure this normalization step has been correctly applied [33] [24].

- Explore Alternative Models: If the ZIG model remains unstable, other approaches like the GEE model with CLR transformation or methods like ANCOM-BC2 can be robust alternatives for handling zero-inflated data [33].

Issue 3: Integrating Normalization and Transformation in a Workflow

Problem: Uncertainty about how to correctly sequence normalization and transformation steps.

Solution: Follow a clear, step-by-step pipeline. The workflow below outlines a robust approach that integrates CTF normalization and CLR transformation, which can be used with a GEE model for differential abundance analysis.

Performance Comparison of Methods

The table below summarizes the performance of various differential abundance analysis methods based on benchmarking studies, highlighting their strengths and weaknesses in handling typical microbiome data challenges.

| Method | Key Model/Approach | Handles Compositionality? | Handles Zeros? | Longitudinal Data? | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DESeq2 | Negative Binomial Model [33] | No (assumes absolute counts) | Moderate (via normalization) | No (without extension) | High sensitivity, but can have high FDR [33] |

| MetagenomeSeq | Zero-Inflated Gaussian (ZIG) Model [33] | Indirectly (via CSS normalization) | Yes (explicitly models zeros) | No | High sensitivity, but can have high FDR [33] |

| metaGEENOME | GEE with CLR & CTF [33] [34] | Yes (via CLR transformation) | Yes (robust model) | Yes | High sensitivity and specificity, good FDR control [33] [34] |

| ALDEx2 | CLR Transformation & Wilcoxon test [33] | Yes (via CLR transformation) | Yes (uses pseudocount) | No | Good FDR control, lower sensitivity [33] |

| ANCOM-BC2 | Linear Model with Bias Correction [33] | Yes (compositionally aware) | Yes (handled in model) | Yes | Good FDR control, high sensitivity [33] |

| Lefse | Kruskal-Wallis/Wilcoxon test & LDA [33] | No (non-parametric on relative abund.) | Moderate | No | High sensitivity, but can have high FDR [33] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Differential Abundance Analysis Using a GEE-CLR-CTF Framework

This protocol is based on the metaGEENOME framework, which is implemented in an R package [33] [34].

- Input Data Preparation: Start with a raw count matrix (OTU/ASV table) where rows are taxa and columns are samples. Ensure metadata is available with information on groups and, for longitudinal data, subject IDs and time points.

- Normalization - CTF:

- Calculate the log2 fold change (M value) and absolute expression count (A value) for each taxon between sample pairs.

- Trim the data by removing the upper and lower percentages (e.g., 30% of M values and 5% of A values).

- Compute the weighted mean of the remaining M values to derive a normalization factor for each sample [33] [34].

- Transformation - CLR:

- Apply the Centered Log-Ratio transformation to the CTF-normalized counts.

- For each sample, calculate the geometric mean of all taxa abundances. Then, for each taxon, take the logarithm of its abundance divided by this geometric mean [33] [34].

CLR(x) = [log(x₁ / G(x)), ..., log(xₙ / G(x))]whereG(x)is the geometric mean.

- Model Fitting - GEE:

- Fit a Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) model using the CLR-transformed data as the response variable.

- Specify the group condition as a predictor. For longitudinal data, specify a subject ID and use an "exchangeable" working correlation structure to account for within-subject correlations [33].

- Perform statistical testing on the model coefficients to identify taxa with significant abundance differences between groups.

Protocol 2: Benchmarking Differential Abundance Tools with Synthetic Data

This protocol is useful for validating findings or testing method performance on a known ground truth.

- Data Simulation: Use a real microbiome dataset as a template. Introduce known, sparse differential abundance signals between groups by selectively increasing or decreasing the counts of a predefined set of taxa. Control parameters like effect size (log fold change) and the proportion of differentially abundant taxa [36] [9].

- Apply Multiple DA Tools: Run several differential abundance analysis methods (e.g., DESeq2, MetagenomeSeq, ANCOM-BC2, ALDEx2, and your method of choice) on the simulated dataset.

- Performance Evaluation: Compare the results from each method against the known ground truth. Calculate performance metrics such as:

- Sensitivity (Power): The proportion of true positives correctly identified.

- False Discovery Rate (FDR): The proportion of significant findings that are false positives.

- Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC): The ability to discriminate between true positives and false positives across different significance thresholds [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item/Category | Function in Microbiome Analysis |

|---|---|

| 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing | Targets conserved ribosomal RNA gene regions to profile and classify microbial community members [33] [35]. |

| Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing | Sequences all DNA in a sample, enabling functional analysis of the microbiome and profiling at the species or strain level [33] [1]. |

| R/Bioconductor Packages | Software environment providing specialized tools (e.g., DESeq2, metagenomeSeq, metaGEENOME) for statistical analysis of high-throughput genomic data [33] [32]. |

| Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) Transformation | A compositional data transformation that converts relative abundances into log-ratios relative to the geometric mean of the sample, making data applicable for standard multivariate statistics [33] [35]. |

| Trimmed Mean of M-values (TMM/CTF) | A normalization method that assumes most taxa are not differentially abundant, using trimmed mean log-ratios to calculate scaling factors that correct for library size differences [33] [34]. |

| Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) | A statistical modeling technique used to analyze longitudinal or clustered data by accounting for within-group correlations, providing population-average interpretations [33] [34]. |

| Zero-Inflated Gaussian (ZIG) Model | A mixture model used in metagenomeSeq that separately models the probability of a zero (dropout) and the abundance level, addressing the excess zeros in microbiome data [33]. |

Microbiome data from 16S rRNA or shotgun metagenomic sequencing presents unique analytical challenges. These data are compositional, meaning the count of one taxon is dependent on the counts of all others in a sample, and they often exhibit high sparsity with many zero values [1] [27]. Normalization is a critical preprocessing step to account for variable sequencing depths across samples, enabling valid biological comparisons [1] [27]. Traditional methods like Total Sum Scaling (TSS) or rarefying have limitations, including sensitivity to outliers and reduced statistical power [1] [37]. This guide introduces next-generation normalization approaches—TaxaNorm and Group-Wise Frameworks (G-RLE, FTSS)—that offer more robust solutions for differential abundance analysis.

The following table summarizes the core features of each advanced normalization method.

Table 1: Comparison of Next-Generation Normalization Methods

| Method Name | Core Innovation | Underlying Model | Key Advantage | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TaxaNorm [38] | Introduces taxon-specific size factors, rather than a single factor per sample. | Zero-Inflated Negative Binomial (ZINB) | Accounts for the fact that sequencing depth effects can vary across different taxa. | Datasets with high heterogeneity; when technical bias correction is a priority. |

| Group-Wise Framework [39] [40] | Calculates normalization factors based on group-level log fold changes, not individual samples. | Based on robust center log-ratio transformations. | Reduces bias in differential abundance analysis, especially with large compositional bias or variance. | Standard case-control differential abundance studies with a binary covariate. |

| ↳ G-RLE [39] [41] | Applies Relative Log Expression (RLE) to group-level log fold changes. | Derived from sample-wise RLE used in RNA-seq. | A simple and interpretable method within the group-wise framework. | A robust starting point for group-wise normalization. |

| ↳ FTSS [39] [41] | Selects a stable reference set of taxa based on proximity to the mode log fold change. | Fold-Truncated Sum Scaling. | Generally more effective than G-RLE at maintaining false discovery rate (FDR) and offers slightly better power [39]. | The recommended method for most analyses using the group-wise framework. |

Experimental Protocols & Implementation

Implementing Group-Wise Normalization (G-RLE and FTSS)

The group-wise framework is designed for differential abundance analysis (DAA) when the covariate of interest is binary (e.g., Case vs. Control) [41]. The following workflow outlines the process of applying G-RLE or FTSS normalization followed by DAA.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

Data Inputs: Prepare your data as an R data frame or matrix.

taxa: A matrix of observed counts with taxa as rows and samples as columns [41].covariate: A binary vector (0/1) indicating group membership for each sample.libsize: A numeric vector of the total library size (sequencing depth) for each sample. Note that this should be the total count before any taxa are removed [41].

Calculate Normalization Offsets: Use the

groupnorm()function to compute offsets using either G-RLE or FTSS.- For G-RLE:

- For FTSS (recommended):

The

prop_referenceparameter (default 0.4) specifies the proportion of taxa to use as the stable reference set [41].

Perform Differential Abundance Analysis: Pass the calculated offsets to a DAA method using the

analysis_wrapper()helper function or directly with standard packages.

Implementing TaxaNorm Normalization

TaxaNorm uses a taxa-specific zero-inflated negative binomial model to normalize data. The workflow involves model fitting, diagnosis, and normalized data output.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

Installation and Data Preparation: Install the TaxaNorm package from CRAN (

install.packages("TaxaNorm")). Prepare your raw count matrix.Model Fitting: Use the

taxanorm()function to fit the ZINB model to your raw count data. This model estimates parameters that account for varying effects of sequencing depth across taxa [38].Diagnosis and Validation: TaxaNorm provides two diagnosis tests to validate the assumption of varying sequencing depth effects across taxa. It is recommended to run these tests to ensure the model is appropriate for your data [38].

Output and Downstream Analysis: The main output of

taxanorm()is a normalized count matrix. This matrix can then be used for various downstream analyses, such as differential abundance testing or data visualization [38].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Table 2: Key Resources for Implementing Advanced Normalization Methods

| Resource Name | Type | Function/Purpose | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

groupnorm() Function [41] |

R Function | Calculates group-wise normalization offsets for G-RLE and FTSS. | Core function for implementing the novel group-wise framework. |

prop_reference Parameter [41] |

Function Parameter (for FTSS) | Controls the proportion of taxa used as the stable reference set in FTSS. | A hyper-parameter; setting to 0.4 is a reasonable default. |

| MetagenomeSeq [39] [41] | R Software Package | A differential abundance analysis method for metagenomic data. | Achieves best results when used with FTSS normalization [39]. |

| TaxaNorm R Package [38] | R Software Package | Implements the TaxaNorm normalization method using a ZINB model. | Provides diagnosis tests for model validation and corrected counts. |

| DESeq2 [41] | R Software Package | A general-purpose differential expression analysis method often used with microbiome data. | Can be used with the offsets generated by the group-wise methods. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

Q1: When should I use a group-wise method like FTSS over a traditional method like TSS or a sample-wise method like RLE? You should strongly consider group-wise normalization when performing differential abundance analysis on a binary covariate, especially in challenging scenarios where the variance between samples is large or there is a strong compositional bias [39] [40]. Simulations show that FTSS maintains the false discovery rate (FDR) better in these settings and can achieve higher statistical power compared to sample-wise methods [39].

Q2: The FTSS method has a prop_reference parameter. How do I choose the right value?

This parameter determines how many taxa are used to calculate the normalization factor. Based on the original publication, a value of 0.40 (meaning 40% of taxa are used as the reference set) is a well-justified default that performs robustly across many scenarios [41]. You may adjust this value, but 0.40 is a solid starting point.

Q3: My study has a continuous exposure or multiple groups. Can I use the current implementation of group-wise normalization? The current group-wise framework, as described in the provided code repository, is designed specifically for binary covariates [41]. For more complex study designs with continuous or multi-level factors, you would need to explore other normalization strategies at this time.

Q4: How does TaxaNorm's approach differ from simply adding a pseudo-count before log-transformation? Adding a pseudo-count is an ad hoc solution that can be sensitive to the chosen value and may not adequately address data sparsity and compositionality [27]. TaxaNorm uses a formal statistical model (Zero-Inflated Negative Binomial) that more flexibly captures the characteristics of microbiome data and provides taxon-specific adjustments, leading to more reliable normalization [38].

Q5: Are there any specific data characteristics that make TaxaNorm a particularly good choice? TaxaNorm was developed specifically to handle the situation where the effect of sequencing depth varies from taxon to taxon, which is a common form of technical bias [38]. If you suspect your dataset has such heterogeneous bias, or if standard normalization methods are over- or under-correcting for certain taxa, TaxaNorm is an excellent option to explore.

Microbiome data derived from 16S rRNA gene sequencing is characterized by several technical challenges, including high dimensionality and compositionality. However, extreme sparsity is one of the most significant hurdles, where it is not unusual for over 90% of data points to be zeros due to the large number of rare taxa that appear in only a small fraction of samples [42]. This sparsity stems from both biological reality—where many microbial taxa are genuinely low abundance—and technical artifacts, including sequencing errors, contamination, and PCR artifacts [42] [43].

Filtering is a critical preprocessing step that addresses this sparsity by removing rare and potentially spurious taxa, thereby reducing the feature space and mitigating the risk of overfitting in downstream statistical and machine learning models [42] [43]. When applied appropriately, filtering reduces data complexity while preserving biological integrity, leading to more reproducible and comparable results [42]. This guide provides troubleshooting and FAQs to help you implement effective filtering strategies within your microbiome data normalization pipeline.

FAQs on Microbiome Data Filtering

Why is filtering necessary if it means removing data?

As a library, NLM provides access to scientific literature. Inclusion in an NLM database does not imply endorsement of, or agreement with, the contents by NLM or the National Institutes of Health. Learn more: PMC Disclaimer | PMC Copyright Notice

- Addressing Sparsity: Microbiome data is extremely sparse, containing a large number of rare taxa observed in as few as 1-5% of samples. This sparsity can complicate statistical analysis and machine learning by increasing noise and the multiple testing burden [42].

- Removing Technical Artifacts: Many rare taxa are not biological signals but are caused by sequencing errors and contamination introduced during wet-lab procedures. Filtering helps remove these technical artifacts, improving data fidelity [42] [44].

- Improving Model Performance: By reducing the number of non-informative features, filtering helps statistical models and machine learning classifiers focus on robust signals, which can improve generalizability and performance [7] [42].

What are the key differences between filtering and contaminant removal?

These are two complementary but distinct approaches to data refinement:

- Filtering: Typically based on prevalence (e.g., the percentage of samples a taxon appears in) and/or abundance (e.g., mean relative abundance). It is an unsupervised approach that does not require control samples [42] [43].

- Contaminant Removal: Uses auxiliary information, such as DNA concentration measurements or the presence of taxa in negative control samples, to identify and remove contaminants introduced during the sequencing process [42] [43].

It is advised to use these methods in conjunction for the most robust results [42] [43].

Will filtering my data affect downstream diversity and differential abundance results?

Yes, but generally in a beneficial way when done appropriately.

- Alpha Diversity: In quality control datasets, filtering has been shown to reduce the magnitude of differences in alpha diversity and alleviate technical variability between different laboratories [42].

- Beta Diversity: Filtering preserves the between-sample similarity (beta diversity), meaning the overall structure of your community data remains intact [42].

- Differential Abundance (DA) and Classification: Filtering retains statistically significant taxa and preserves the ability of models like Random Forest to classify diseases, as measured by the Area Under the Curve (AUC) [42]. Note that the choice of DA method can drastically impact results, and some methods may be more sensitive to filtering than others [37].

How should I decide on specific filtering thresholds?

There is no universal threshold, but the decision should be guided by your specific data and biological expectations.

- Biological Rationale: "Will process X improve the fidelity of my data?" is a useful guiding principle. The goal is to remove data not meaningful to your study without introducing new biases [44].

- Common Practices: For a stable community from a controlled environment (e.g., mice in a lab), you might filter out features appearing in only one sample, as these are unlikely to be real biological signals [44].

- Principled Methods: Instead of relying on arbitrary "rules of thumb," consider using principled filtering methods like the PERFect algorithm, which provides a statistical framework for deciding which taxa to remove [42].

Troubleshooting Common Filtering Scenarios

Problem: Inconsistent results after filtering in differential abundance testing.

- Background: A large-scale evaluation of 14 differential abundance (DA) methods on 38 datasets found that different tools identified drastically different numbers and sets of significant taxa, and that these results were further influenced by data pre-processing, including filtering [37].

- Solution:

- Do not rely on a single DA method. The number of significant features identified by a single tool can correlate with dataset-specific factors like sample size [37].

- Use a consensus approach. Methods like ALDEx2 and ANCOM-II have been shown to produce more consistent results across studies and agree best with the intersect of results from different methods [37].

- Report your filtering criteria transparently. Ensure that your filtering is independent of the test statistic (e.g., filter based on overall prevalence, not prevalence within one group) [37].