Microbiome Differential Abundance Analysis: A Comprehensive Benchmarking Review for Robust Biomarker Discovery

Differential abundance (DA) analysis is a cornerstone of microbiome research, essential for identifying microbial biomarkers associated with health and disease.

Microbiome Differential Abundance Analysis: A Comprehensive Benchmarking Review for Robust Biomarker Discovery

Abstract

Differential abundance (DA) analysis is a cornerstone of microbiome research, essential for identifying microbial biomarkers associated with health and disease. However, the absence of a gold-standard method and the unique statistical challenges of microbiome data—including compositionality, sparsity, and zero-inflation—lead to significant variability in results depending on the chosen method. This review synthesizes evidence from recent large-scale benchmarking studies to provide a foundational understanding of these challenges, a comparative evaluation of popular DA methods, and practical strategies for method selection and optimization. We highlight that no single method performs optimally across all datasets, but consensus approaches and careful consideration of data characteristics can significantly improve the robustness and reproducibility of findings for biomedical and clinical applications.

The Core Challenges in Microbiome Differential Abundance Analysis

In microbiome research, a fundamental challenge arises from the very nature of the data generated by sequencing technologies. Microbiome sequencing data are compositional, meaning they convey only relative abundance information rather than absolute quantities. This characteristic stems from the laboratory process where samples are normalized to a standard amount of genetic material before sequencing, removing information about total microbial load. Consequently, the observed abundance of any single taxon is intrinsically linked to the abundances of all other taxa in the sample. This compositionality can lead to spurious findings if not properly addressed, as changes in one taxon's abundance can create illusory changes in others. This article explores why this problem demands specialized statistical methods and compares the performance of various differential abundance (DA) analysis approaches within this critical context.

The Core Challenge: Compositional Data in Microbiome Research

What Makes Data Compositional?

Compositional data exists in a constrained space called the "simplex" where only relative information is meaningful. In practice, this means that an observed increase in one microbial taxon's relative abundance could result from:

- A true increase in its absolute abundance

- A decrease in the absolute abundances of other taxa

- Any combination of these changes

One study illustrates this with a hypothetical community: if the absolute abundances of four species change from (7, 2, 6, 10) to (2, 2, 6, 10) million cells, only the first species is truly differential. However, the observed compositions would be (28%, 8%, 24%, 40%) versus (10%, 10%, 30%, 50%). Based on composition alone, multiple scenarios (including three or four differential taxa) are equally plausible without assuming signal sparsity [1].

The Consequences for Differential Abundance Analysis

The compositional nature of microbiome data severely impacts DA analysis. When standard statistical methods designed for absolute abundances are applied to relative data, they typically produce unacceptably high false positive rates. Research has demonstrated that the problem becomes particularly severe in datasets with widespread changes in abundance across many features [2]. One analysis found that methods not accounting for compositionality could identify drastically different numbers and sets of significant taxa compared to compositional methods, with the number of features identified often correlating more with technical aspects like sample size and sequencing depth than true biological signals [3].

Comparing Methodological Approaches to Compositionality

Differential abundance methods employ different strategies to handle compositional data, which can be broadly categorized as follows:

Compositional Data Analysis (CoDa) Methods

These methods explicitly acknowledge and model the compositional nature of the data:

- ALDEx2 uses Bayesian methods to estimate the underlying relative proportions via Monte Carlo sampling from a Dirichlet distribution, then applies a centered log-ratio (CLR) transformation [3] [1].

- ANCOM and ANCOM-BC use an additive log-ratio transformation, comparing the ratio of each taxon to a reference taxon across sample groupings [3] [1].

- PhILR and similar approaches use phylogenetic information to create balances that transform the data into an unconstrained space.

Robust Normalization Methods

These methods attempt to calculate size factors that represent the non-differential portion of the community:

- DESeq2 uses the median of ratios method (relative log expression) [1].

- edgeR uses the trimmed mean of M-values (TMM) [1].

- metagenomeSeq employs cumulative sum scaling (CSS) [1].

Standard Normalization Approaches

These simpler methods are more susceptible to compositional effects:

- Total Sum Scaling (proportions or percentages)

- Rarefaction followed by standard tests [3]

- Counts Per Million (CPM) and similar transformations

Table 1: Categories of Differential Abundance Methods and Their Approaches to Compositionality

| Method Category | Representative Methods | Core Approach to Compositionality | Theoretical Strength |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compositional (CoDa) | ANCOM, ANCOM-BC, ALDEx2 | Explicit modeling of data as compositions | Directly addresses the fundamental data constraint |

| Robust Normalization | DESeq2, edgeR, metagenomeSeq | Estimating size factors from stable features | Mitigates effects when most features are non-differential |

| Standard Normalization | Wilcoxon on proportions, t-test on rarefied data | Simple scaling to total reads | Computational simplicity |

Performance Comparison: Experimental Evidence

Benchmarking Studies and Their Designs

To objectively evaluate DA method performance, researchers have employed various benchmarking approaches:

Real Data-Based Simulations: These implant known signals into real taxonomic profiles, creating a realistic ground truth for evaluation. One 2024 study developed a sophisticated framework that implants calibrated abundance shifts and prevalence changes into real datasets, quantitatively validating that their simulated data closely resembles real data from disease association studies [4].

Large-Scale Method Comparisons: Studies apply multiple DA methods to numerous real datasets to assess concordance. One analysis tested 14 methods on 38 different 16S rRNA gene datasets with 9,405 total samples [3].

Parametric Simulations: These generate data from specific statistical distributions, though their biological realism has been questioned [4].

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Differential Abundance Methods Across Benchmarking Studies

| Method | False Discovery Rate Control | Power/Sensitivity | Consistency Across Datasets | Performance with Strong Compositional Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALDEx2 | Good control [3] [1] | Lower power in some studies [3] | High consistency with method consensus [3] | Robust due to explicit compositional approach |

| ANCOM/ANCOM-BC | Good control [3] [1] | Moderate to high power | Most consistent with method intersections [3] | Specifically designed for compositionality |

| MaAsLin2 | Variable performance | Moderate power | Moderate consistency | Handles covariates but compositional effects vary |

| DESeq2 | Can be inflated [1] | Generally high power | Variable across datasets | Improved with robust normalization but not optimal |

| edgeR | Can be inflated [3] [1] | Generally high power | Variable across datasets [3] | Similar issues as DESeq2 |

| limma-voom | Variable (can be inflated) | High power [3] | Variable across datasets | Moderate with TMM normalization |

| LEfSe | Can be inflated | Moderate power | Moderate consistency | Uses relative abundances directly |

| LinDA | Good control | High power | Good consistency | Specifically designed for correlated/compositional data |

Key Findings from Performance Benchmarks

No single method dominates across all scenarios. Method performance depends on specific dataset characteristics such as sample size, effect size, proportion of differentially abundant taxa, and sequencing depth [3] [1].

Methods explicitly addressing compositional effects (ALDEx2, ANCOM, ANCOM-BC) generally demonstrate better false discovery rate control. However, they may suffer from reduced statistical power in certain settings [1].

The concordance between different DA methods is often surprisingly low. One study on Parkinson's disease gut microbiome datasets found that only 5-22% of taxa were called differentially abundant by the majority of methods, with concordances between individual methods ranging from 1% to 100% [5].

Filtering rare taxa before analysis generally improves concordance between methods. The same Parkinson's disease study observed that concordances increased by 2-32% when rarer taxa were removed before testing [5].

Experimental Protocols for Method Evaluation

Signal Implantation in Real Data

The most realistic evaluation approach implants calibrated signals into real taxonomic profiles [4]:

Baseline Data Selection: A real dataset from healthy individuals serves as the baseline (e.g., the Zeevi WGS dataset).

Group Assignment: Samples are randomly assigned to case and control groups.

Signal Implantation: For selected features, counts in the case group are modified through:

- Abundance Scaling: Multiplying counts by a constant factor (e.g., 2-fold, 5-fold, 10-fold increase)

- Prevalence Shift: Shuffling a percentage of non-zero entries across groups

- Combined Approaches: Applying both abundance and prevalence changes

Method Application: Multiple DA methods are applied to the same manipulated datasets.

Performance Assessment: Methods are evaluated based on their ability to detect the implanted signals while controlling false discoveries of non-implanted features.

This approach preserves the complex correlation structures and characteristics of real microbiome data while creating a known ground truth.

Assessment Metrics

Comprehensive benchmarking studies evaluate methods using multiple metrics [6]:

- False Positive Rate (FPR): Proportion of non-differential features incorrectly identified as significant

- False Discovery Rate (FDR): Proportion of significant features that are actually non-differential

- Recall (Sensitivity): Proportion of truly differential features correctly identified

- Precision: Proportion of significant features that are truly differential

- Area Under Precision-Recall Curve: Overall performance across significance thresholds

- Computational Efficiency: Runtime and memory requirements

Visualizing the Impact of Compositionality

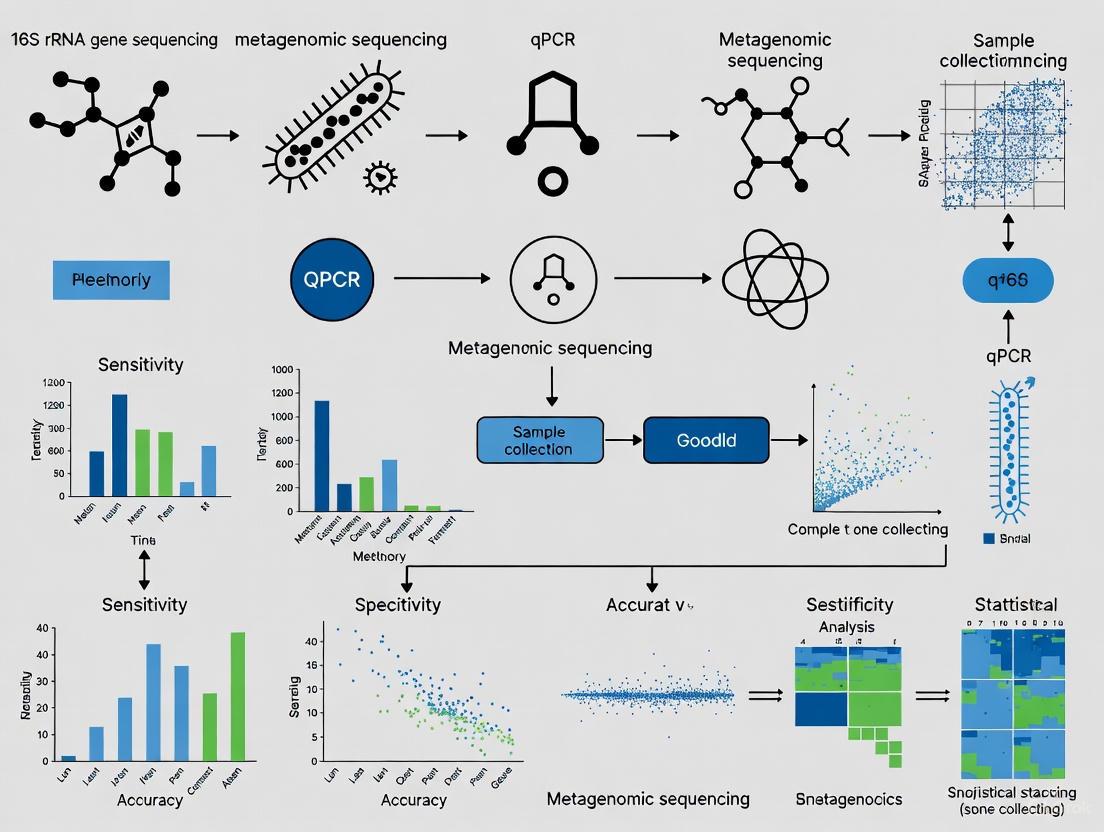

The diagram below illustrates how compositional effects can lead to misinterpretation of microbiome data, and how different methodological approaches attempt to address this challenge:

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools for Differential Abundance Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Compositionality |

|---|---|---|---|

| benchdamic | R Package | Comprehensive benchmarking of DA methods | Enables comparison of compositional vs. non-compositional approaches [7] |

| ALDEx2 | R Package | Bayesian compositional DA analysis | Explicitly models data as compositions using CLR transformation [3] [1] |

| ANCOM-BC | R Package | Compositional DA analysis with bias correction | Addresses compositionality through log-ratio transformations [1] |

| ZicoSeq | R Package | Optimized DA procedure for microbiome data | Designed to address major challenges including compositionality [1] |

| metaSPARSim | R Package | Microbiome count data simulation | Generates realistic compositional data for method evaluation [6] |

| GMPR | R Function | Size factor calculation for sparse data | Robust normalization specifically for microbiome data [1] |

| QIIME 2 | Pipeline | Microbiome analysis platform | Integrates some compositional methods in analysis workflows |

| MetaPhlAn | Tool | Taxonomic profiling from metagenomes | Generates relative abundance tables for compositional analysis |

The compositional nature of microbiome sequencing data presents a fundamental challenge that demands specialized analytical approaches. Evidence from multiple comprehensive benchmarking studies reveals that:

Standard statistical methods applied to relative abundance data frequently produce misleading results due to uncontrolled false positive rates.

Methods explicitly designed for compositional data (ALDEx2, ANCOM/ANCOM-BC) generally provide more reliable inference but may have limitations in statistical power or computational requirements.

No single method performs optimally across all datasets and study designs, suggesting that a consensus approach using multiple complementary methods may be most robust.

For researchers investigating microbiome differential abundance, the current evidence supports:

- Prioritizing methods that explicitly address compositionality

- Applying multiple DA methods to assess result consistency

- Using realistic simulation approaches for method evaluation

- Incorporating independent validation when possible

As the field advances, continued development and refinement of compositional data analysis methods will be essential for drawing accurate biological conclusions from relative abundance data and advancing our understanding of microbiome function in health and disease.

In microbiome research, high-throughput sequencing data is characterized by a high proportion of zero values, often exceeding 70% of the data points in a typical dataset [1]. These zeros present a fundamental analytical challenge because they can arise from two fundamentally different sources: biological absence (true absence of a microbe in its habitat, known as structural zeros) or technical noise (failure to detect a microbe due to limited sequencing depth or other technical artifacts, known as sampling zeros) [1] [8]. This distinction is crucial for accurate biological interpretation, as misclassifying these zeros can lead to false discoveries in differential abundance (DA) analysis and flawed conclusions about microbiome-disease relationships [9] [10].

The zero-inflation problem is exacerbated by several inherent characteristics of microbiome data. First, data is compositional, meaning that sequencing only provides information on relative abundances, where an increase in one taxon necessarily leads to apparent decreases in others [3] [11]. Second, microbiome data exhibits high dimensionality (more taxa than samples) and over-dispersion (variance exceeding the mean) [12] [1]. These characteristics, combined with zero-inflation, create a complex statistical landscape that requires specialized methodological approaches for robust analysis.

Methodological Landscape: Strategies for Handling Zero-Inflation

Multiple computational strategies have been developed to address zero-inflation in microbiome data, each with distinct theoretical foundations and implementation approaches. These methods can be broadly categorized into several philosophical frameworks.

Normalization and Transformation-Based Approaches

Some methods address zero-inflation through robust normalization and compositional transformations. The centered log-ratio (CLR) transformation, used by ALDEx2, avoids the need for a reference taxon by using the geometric mean of all taxa as the denominator [12] [3]. The Counts adjusted with Trimmed Mean of M-values (CTF) normalization assumes most taxa are not differentially abundant and uses double-trimming (M values by 30%, A values by 5%) to calculate normalization factors resistant to outlier effects [12]. These approaches attempt to mitigate the impact of technical zeros without explicitly modeling their source.

Explicit Zero-Inflation Modeling

A more direct approach involves explicitly modeling the two types of zeros using specialized statistical distributions. Zero-inflated models (e.g., ZINB, ZINBMM) treat the observed data as arising from a mixture process: a degenerate distribution generating structural zeros and a count distribution (often negative binomial) generating the counts, including sampling zeros [1] [13]. These methods can theoretically distinguish between biological and technical zeros but require strong parametric assumptions that may not always hold in real data [13].

Denoising and Imputation Strategies

An alternative paradigm treats technical zeros as missing data that can be imputed. Methods like mbDenoise use a zero-inflated probabilistic PCA (ZIPPCA) framework to learn latent structures and recover true abundance levels using posterior means [8]. The BMDD framework employs a BiModal Dirichlet Distribution to model abundance distributions more flexibly, potentially capturing taxa that behave differently across conditions [10]. These approaches borrow information across samples and taxa to distinguish signal from noise.

Distribution-Free Approaches

More recently, distribution-free methods like ZINQ-L have emerged that avoid specific parametric assumptions. ZINQ-L uses a two-part quantile regression approach that models both the presence-absence component (using logistic regression) and the abundance distribution (using quantile regression) without assuming negative binomial or other specific distributions [13]. This robustness comes at the cost of potentially reduced statistical power when parametric assumptions are met.

Table 1: Methodological Approaches to Zero-Inflation in Microbiome Data

| Method Category | Representative Tools | Core Approach | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normalization & Transformation | ALDEx2, metaGEENOME | CLR transformation, robust normalization | No need for explicit zero model, handles compositionality | May not fully address structural zeros |

| Explicit Zero Modeling | ZINBMM, metagenomeSeq | Zero-inflated negative binomial models | Explicitly models biological vs. technical zeros | Strong parametric assumptions, computational complexity |

| Denoising & Imputation | mbDenoise, BMDD, mbImpute | Low-rank approximation, posterior estimation | Recovers potentially true abundances, leverages correlations | Risk of over-imputation, model misspecification |

| Distribution-Free | ZINQ-L | Quantile regression, rank-based tests | Robust to distribution violations, detects heterogeneous signals | May have reduced power if parametric assumptions hold |

Performance Benchmarking: Experimental Evidence

Benchmarking Frameworks and Challenges

Evaluating the performance of differential abundance methods faces the fundamental challenge of lacking a "gold standard" for real datasets [3] [11]. To address this, researchers have developed various simulation frameworks, though each has limitations. Parametric simulations generate data from specific statistical distributions but may lack biological realism and create circular arguments where methods perform best on data simulated from their own underlying models [3] [11]. Resampling approaches manipulate real datasets by implanting known signals through abundance scaling or prevalence shifts, better preserving the characteristics of real data [11].

Recent advances in benchmarking include signal implantation frameworks that introduce calibrated differential abundance signals into real taxonomic profiles by multiplying counts in one group with a constant factor (abundance scaling) and/or shuffling non-zero entries across groups (prevalence shift) [11]. This approach maintains the natural correlation structure and distributional properties of real microbiome data while providing a known ground truth for evaluation.

Comparative Performance of Methods

Comprehensive benchmarking studies across multiple datasets reveal substantial variability in method performance. A large-scale evaluation of 14 DA tools across 38 real datasets found that different methods identified "drastically different numbers and sets" of significant taxa, with the percentage of significant features ranging from 0.8% to 40.5% depending on the method and filtering approach [3]. This variability underscores the profound impact of methodological choices on biological interpretations.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Differential Abundance Methods Based on Large-Scale Benchmarking

| Method | False Discovery Rate Control | Sensitivity | Robustness to Compositionality | Longitudinal Data Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANCOM-BC/ANCOM-II | Good | Moderate | Excellent | Limited |

| ALDEx2 | Good | Moderate | Excellent | Limited |

| metaGEENOME | Good | High | Good | Excellent (GEE framework) |

| Limma-voom | Variable (inflation observed) | High | Moderate | Limited |

| edgeR | Poor (FDR inflation) | High | Poor | Limited |

| DESeq2 | Poor (FDR inflation) | High | Poor | Limited |

| ZINQ-L | Good | Moderate-High | Good | Excellent |

| Wilcoxon on CLR | Variable | High | Good | Limited |

Methods specifically designed to address compositional effects (ANCOM-BC, ALDEx2) generally demonstrate better false discovery rate (FDR) control, though sometimes at the cost of reduced sensitivity [1] [3]. Tools adapted from RNA-seq analysis (edgeR, DESeq2) often achieve high sensitivity but may fail to adequately control FDR when applied to microbiome data [12] [3]. The recently proposed metaGEENOME framework, which integrates CTF normalization with CLR transformation and Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE), has demonstrated both high sensitivity and specificity while effectively controlling FDR in both cross-sectional and longitudinal settings [12].

Impact of Data Characteristics on Performance

Method performance is strongly influenced by dataset characteristics. Sample size significantly affects error control, with many methods achieving proper FDR control only at larger sample sizes [14]. The percentage of differentially abundant features affects methods differently, with compositional methods performing better when fewer features are differential (sparsity assumption) [1]. Sequencing depth and effect size also interact with method performance, with some methods exhibiting better power for detecting large effects while others are more sensitive to small, consistent changes [14] [11].

Experimental Protocols for Method Evaluation

Signal Implantation Protocol for Realistic Benchmarking

The following protocol, adapted from [11], enables realistic performance evaluation with known ground truth:

Baseline Data Selection: Select a real microbiome dataset from healthy individuals or control conditions with sufficient sample size and diversity.

Group Randomization: Randomly assign samples to two groups (e.g., case-control) while maintaining similar overall community structure.

Signal Implantation:

- Abundance Scaling: Select a subset of taxa to be differentially abundant. Multiply the counts of these taxa in the "case" group by a constant scaling factor (typically 2-10×) while preserving compositionality.

- Prevalence Shift: For selected taxa, shuffle a percentage of non-zero entries between groups to create differential prevalence without necessarily changing abundance in detected samples.

- Combined Effects: Implement both abundance and prevalence changes to mimic realistic biological scenarios.

Method Application: Apply DA methods to the implanted dataset using their recommended normalization procedures and parameter settings.

Performance Calculation: Compare identified significant taxa to the known implanted signals to calculate sensitivity, specificity, false discovery rate, and other performance metrics.

This approach preserves the natural covariance structure and distributional properties of real microbiome data while providing a known ground truth for evaluation.

Cross-Study Validation Protocol

To complement simulated benchmarks, the following protocol uses real data to assess result consistency:

Dataset Curation: Collect multiple independent datasets addressing similar biological questions (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease vs. healthy controls).

Method Application: Apply DA methods to each dataset independently using consistent preprocessing and filtering criteria.

Result Concordance Assessment: Identify taxa consistently detected as significant across multiple independent studies.

Benchmark Evaluation: Compare each method's consistency using metrics like the Jaccard index between result sets and agreement with a consensus across methods.

This approach leverages natural replication across studies to assess method robustness without requiring a known ground truth [3].

Visualization of Analytical Approaches

Visualization Title: Analytical Framework for Zero-Inflated Microbiome Data

This diagram illustrates the four major methodological approaches for handling zero-inflation in microbiome data analysis. Each pathway represents a distinct philosophical and statistical framework for distinguishing biological absences from technical noise, ultimately leading to differential abundance results.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Zero-Inflation Analysis in Microbiome Research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| metaGEENOME | Differential Abundance | GEE-based framework for cross-sectional and longitudinal data | R package |

| ALDEx2 | Differential Abundance | Compositional DA analysis using CLR transformation | R package |

| ANCOM-BC | Differential Abundance | Compositional DA with bias correction | R package |

| mbDenoise | Denoising | Zero-inflated probabilistic PCA for abundance recovery | R package |

| BMDD | Imputation | BiModal Dirichlet Distribution for zero imputation | R package |

| ZINQ-L | Differential Abundance | Zero-inflated quantile regression for longitudinal data | R package |

| edgeR/DESeq2 | Differential Abundance | Negative binomial models adapted from RNA-seq | R package |

| sparseDOSSA2 | Simulation | Realistic microbiome data simulation with sparsity | R package |

| QIIME 2 | Pipeline | Integrated microbiome analysis with plugin architecture | Python |

| phyloseq | Data Structure | Representation and manipulation of microbiome data | R package |

The zero-inflation problem remains a central challenge in microbiome data analysis, with no single method universally outperforming others across all scenarios. Based on current evidence, we recommend:

Method Selection Should Be Context-Dependent: Choose methods based on study design (cross-sectional vs. longitudinal), sample size, and expected effect sizes. For longitudinal studies, methods like metaGEENOME or ZINQ-L that account for within-subject correlations are essential [12] [13].

Employ a Consensus Approach: Given the variability in results across methods, using multiple complementary approaches and focusing on consistently identified taxa provides more robust biological conclusions [3].

Prioritize False Discovery Rate Control: In biomarker discovery applications, methods with demonstrated FDR control (ANCOM-BC, ALDEx2, metaGEENOME) should be preferred over methods with known FDR inflation [12] [1] [3].

Validate with Realistic Simulations: Benchmark method performance on data that resembles real microbiome datasets, using signal implantation or resampling approaches rather than purely parametric simulations [11].

As microbiome research progresses toward more complex study designs and integration with other omics technologies, continued development of robust statistical methods for handling zero-inflation will remain essential for translating microbial patterns into meaningful biological insights.

Sequencing Depth Variation and Its Impact on False Discoveries

Sequencing depth variation presents a significant challenge in microbiome analysis, directly impacting the false discovery rate (FDR) in differential abundance (DA) testing. This review synthesizes findings from recent benchmarking studies to evaluate how normalization strategies and DA methods control for false positives induced by uneven sequencing depths. Evidence confirms that method choice drastically influences outcomes, with certain tools exhibiting superior FDR control in the face of compositional bias and depth variation. This guide provides an objective comparison of methodological performance to inform robust biomarker discovery in microbiome research.

In microbiome studies, sequencing depth—the number of reads assigned to a sample—inevitably varies across samples. This variation is not merely a technical nuisance; it fundamentally challenges the integrity of differential abundance analysis by introducing compositional bias [15]. Since microbiome sequencing data are compositional (inherently summing to a total for each sample), an increase in the abundance of one taxon creates an apparent decrease in others, regardless of their true biological behavior. When sequencing depth correlates with a variable of interest (e.g., disease state), this bias can lead to a high rate of false discoveries, where taxa are incorrectly identified as differentially abundant [1] [15]. The choice of DA method and its underlying normalization strategy is therefore critical for controlling the False Discovery Rate (FDR). This guide compares the performance of contemporary DA methods, focusing on their resilience to sequencing depth variation, to provide actionable insights for researchers and drug development professionals.

Core Concepts and Experimental Frameworks

Key Challenges in Microbiome Differential Abundance Analysis

Microbiome data possesses three key characteristics that complicate DA analysis and make it susceptible to the effects of sequencing depth variation:

- Compositionality: Data represent relative, not absolute, abundances. A change in one taxon's abundance causes apparent changes in all others, creating spurious dependencies [1] [16] [15].

- Zero Inflation: A high proportion of zero counts (exceeding 70% in typical datasets) can arise from either biological absence (structural zeros) or undersampling (sampling zeros) [1].

- High Dimensionality: The number of taxa (

p) often far exceeds the number of samples (n), increasing the multiple testing burden and the potential for false positives [16].

These characteristics mean that without proper statistical control, sequencing depth variation can be misinterpreted as biological signal.

Standardized Evaluation Protocols

To objectively assess DA method performance, researchers employ benchmarking studies that use both real and simulated data. The typical workflow is as follows:

Diagram 1: Experimental Workflow for Benchmarking DA Methods. Benchmarking studies use real datasets as templates for simulation, applying multiple DA methods to data with known truths to calculate performance metrics like FDR [3] [17].

Key experimental approaches include:

- Large-Scale Empirical Comparison: Applying multiple DA tools to many real-world datasets (e.g., 38 two-group 16S rRNA gene datasets with 9,405 total samples) to assess result concordance and the scale of identified differences [3].

- Real Data-Based Simulation: Using real datasets as templates to simulate synthetic data with known differentially abundant taxa. This creates a "ground truth" for directly evaluating sensitivity, specificity, and FDR control [1] [17].

- Null Dataset Analysis: Artificially subsampling datasets into groups where no biological differences exist. This tests a method's false positive rate when the null hypothesis is true [3].

Performance Comparison of Differential Abundance Methods

Variability in Results and False Discovery Rates

Different DA methods applied to the same dataset can identify drastically different sets of significant taxa. One large-scale comparison found that the percentage of taxa identified as significant varied widely, with means ranging from 0.8% to 40.5% across methods and datasets [3]. This inconsistency highlights the risk of cherry-picking methods to confirm hypotheses.

The following table summarizes the performance of commonly used DA methods regarding FDR control and power, particularly under sequencing depth variation:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Common Differential Abundance Methods

| Method Category | Method | Key Strategy | FDR Control | Statistical Power | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normalization-Based | DESeq2 (Witten et al.) | Negative binomial model; Relative Log Expression (RLE) normalization. | Variable; can be inflated [1]. | High | Assumes most taxa are not differential for RLE normalization [15]. |

| edgeR (Law et al.) | Negative binomial model; Trimmed Mean of M-values (TMM) normalization. | Can be unacceptably high; sensitive to compositionality [3] [1]. | High | FDR can be inflated when compositional bias is large [3] [15]. | |

| metagenomeSeq (Paulson et al.) | Zero-inflated Gaussian; Cumulative Sum Scaling (CSS). | Can be high in some settings [3] [16]. | High | Performance improves with group-wise normalization like FTSS [15]. | |

| Compositional Data Analysis | ALDEx2 (Fernandes et al.) | Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) transformation; Dirichlet prior. | Robust, among the best for FDR control [3] [1] [16]. | Lower than some methods, but results are consistent [3] [1]. | Addresses compositionality directly; produces consistent results across studies [3]. |

| ANCOM / ANCOM-BC (Mandal et al.) | Additive Log-Ratio (ALR) transformation; accounts for compositionality. | Robust, good FDR control [1] [16]. | Moderate to high | Less sensitive to normalization; ANCOM-BC includes bias correction [1]. | |

| LinDA (Zhou et al.) | Linear model on log-transformed counts after pseudo-count addition. | Good FDR control with proper normalization [15]. | Moderate | ||

| Other Approaches | LEfSe (Segata et al.) | Non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test; Linear Discriminant Analysis. | Can be inflated without rarefaction [3]. | Intermediate | Often used with rarefied data to control for depth [3]. |

| limma-voom (Ritchie et al.) | Linear models with precision weights; TMM normalization. | Can be inflated in some challenging settings [3] [1]. | High | Can identify a very high number of significant taxa in some datasets [3]. | |

| ZicoSeq (Yang et al.) | Omnibus test; uses GMPR normalization. | Generally robust [1]. | Among the highest | Designed as an optimized procedure to address major DAA challenges [1]. |

The Critical Role of Normalization in Controlling False Discoveries

Normalization is the process of adjusting counts to account for technical variation like sequencing depth before DA testing. The choice of normalization strategy is a primary factor influencing FDR.

Table 2: Comparison of Normalization Methods and Their Impact on FDR

| Normalization Method | Description | Impact on FDR & Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Total Sum Scaling (TSS) | Scaling counts by total library size (i.e., converting to proportions). | Prone to severe compositional bias; high FDR as it ignores depth variation beyond total counts [15]. |

| Relative Log Expression (RLE) | Computes factor from median ratio of counts to a geometric mean sample. | Struggles when a large proportion of taxa are differential or variance is high; can lead to inflated FDR [15]. |

| Trimmed Mean of M-values (TMM) | Weighted trimmed mean of log-ratabs (M-values) between samples. | Can be biased if the reference sample is unusual; performance suffers with strong compositional effects [15]. |

| Cumulative Sum Scaling (CSS) | Uses a percentile of the cumulative distribution of counts to determine a scaling factor. | More robust than TSS, but can still struggle with FDR control in challenging scenarios [15]. |

| Group-Wise RLE (G-RLE) | Applies RLE normalization within each pre-defined group separately. | Improved FDR control and power by addressing group-level compositional bias [15]. |

| Fold Truncated Sum Scaling (FTSS) | Uses group-level summary statistics to identify stable reference taxa for normalization. | Superior FDR control and power, especially when used with metagenomeSeq [15]. |

The relationship between normalization, DA methods, and FDR can be conceptualized as follows:

Diagram 2: Pathway from Sequencing Depth Variation to False Discoveries and Mitigation Strategies. Sequencing depth variation introduces compositional bias, which is exacerbated by inappropriate normalization, leading to false discoveries. Group-wise normalization and compositional data analysis methods can mitigate this bias [3] [1] [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Robust Differential Abundance Analysis

| Item | Category | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| R/Bioconductor | Software Environment | Provides a platform for installing and running the majority of specialized DA tools. | Essential for computational reproducibility. |

| ALDEx2 | Software Package | Implements a compositional data approach using CLR transformation and Dirichlet-multinomial model. | Robust FDR control; good for consensus analysis [3] [16]. |

| ANCOM-BC | Software Package | Implements a bias-corrected compositional method using ALR transformation. | Robust FDR control; less sensitive to normalization choices [1]. |

| DESeq2 / edgeR | Software Package | General-purpose methods for count data, widely adapted for microbiome analysis. | Can have high FDR if not used carefully; powerful but requires caution [3] [1]. |

| ZicoSeq | Software Package | An optimized omnibus test that combines strengths of existing methods. | Generally robust FDR and high power as per its design [1]. |

| GMPR / Wrench | Normalization Tool | Provides robust normalization factors specifically for zero-inflated data. | Can be used to pre-process data for methods like ZicoSeq or other models [1] [15]. |

| Group-Wise Normalization (G-RLE, FTSS) | Normalization Protocol | Advanced normalization that calculates factors based on group-level statistics. | Crucial for improving FDR control with normalization-based methods like metagenomeSeq and edgeR [15]. |

Sequencing depth variation is a potent source of false discoveries in microbiome differential abundance analysis. The evidence demonstrates that the choice of analytical method and normalization strategy is paramount. Methods that directly address data compositionality, such as ALDEx2 and ANCOM-BC, generally offer more robust FDR control. Furthermore, emerging group-wise normalization techniques like FTSS and G-RLE significantly improve the performance of model-based methods. Given the substantial variability in results produced by different tools, a consensus approach—using multiple DA methods and focusing on overlapping results—is highly recommended to ensure biological findings are robust and reliable.

A fundamental challenge in microbiome research lies in the inherent nature of sequencing data, which only captures relative proportions of microbial taxa within a sample rather than their absolute quantities. This compositional property means that an observed increase in one taxon's relative abundance can result from either its true expansion or the decline of other community members [3] [1]. Consequently, distinguishing between absolute abundance changes (genuine cellular proliferation or reduction) and relative abundance changes (shifts in community structure) remains a critical methodological frontier. This distinction carries profound implications for biological interpretation, particularly in disease contexts where discerning causative pathogens from compensatory population shifts is essential for developing effective interventions. The field has responded with diverse statistical methods addressing this challenge, each making different assumptions about the underlying nature of abundance changes and employing distinct strategies to mitigate compositional effects.

Theoretical Foundations: Absolute and Relative Abundance Frameworks

The Compositional Data Problem

Microbiome sequencing data are fundamentally compositional because the total read count (library size) does not reflect the absolute microbial load at the sampling site [1]. This means that all abundance measurements are constrained to sum to a total, creating dependencies between all taxa in a sample. To illustrate, consider a hypothetical community with four species whose baseline absolute abundances are 7, 2, 6, and 10 million cells per unit volume [1]. After an experimental treatment, the absolute abundances become 2, 2, 6, and 10 million cells, indicating that only the first species has truly changed in absolute terms. However, the compositional profiles would shift from (28%, 8%, 24%, 40%) to (10%, 10%, 30%, 50%), making it appear that three taxa have changed relative to one another. Without additional assumptions or measurements, distinguishing the true scenario (one differentially abundant taxon) from other possibilities is mathematically indeterminate from composition data alone [1].

Methodological Approaches to Compositionality

Differential abundance methods employ different strategies to address compositionality, largely determining whether they target absolute or relative changes:

Compositional Data Analysis Methods explicitly acknowledge the relative nature of the data and use log-ratio transformations to conduct meaningful statistical tests. The centered log-ratio (CLR) transformation, used by ALDEx2, divides each taxon's abundance by the geometric mean of all taxa in a sample, creating ratios that are more amenable to standard statistical tests [3] [16]. The additive log-ratio (ALR) transformation, implemented in ANCOM, uses a reference taxon as denominator, though identifying an appropriate invariant reference presents challenges [3] [16]. These methods generally identify taxa that change relative to the community structure.

Normalization-Based Methods attempt to recover absolute abundance signals by applying scaling factors that estimate technical variation. Methods like DESeq2 (using relative log expression normalization), edgeR (using trimmed mean of M-values), and metagenomeSeq (using cumulative sum scaling) incorporate these factors as offsets in count-based models [1] [15]. The underlying assumption is that most taxa are not differentially abundant, allowing robust estimation of scaling factors from the non-differential majority [15]. When this sparsity assumption holds, these methods can approximate absolute abundance changes.

Robust Normalization Frameworks represent newer approaches that conceptualize normalization as a group-level rather than sample-level task. Methods like group-wise relative log expression (G-RLE) and fold-truncated sum scaling (FTSS) use between-group comparisons to calculate normalization factors, demonstrating improved false discovery rate control in challenging scenarios with large compositional biases [15].

Table 1: Methodological Approaches to Compositionality in Differential Abundance Analysis

| Category | Representative Methods | Target Abundance | Core Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compositional Data Analysis | ALDEx2, ANCOM, ANCOM-BC | Relative | Log-ratio transformations with different denominator choices |

| Normalization-Based | DESeq2, edgeR, metagenomeSeq | Absolute (under sparsity assumption) | Sample-specific scaling factors in count-based models |

| Group-Wise Normalization | G-RLE, FTSS with metagenomeSeq | Absolute | Between-group comparisons for normalization factor calculation |

| Elementary Methods | Wilcoxon test on CLR data | Relative | Non-parametric tests on transformed data |

Experimental Benchmarking: Performance Across Methodologies

Large-Scale Method Comparisons

The 2022 benchmark by Nearing et al. examined 14 differential abundance tools across 38 16S rRNA datasets with 9,405 samples from diverse environments [3]. This study revealed that different methods identified drastically different numbers and sets of significant taxa, with the percentage of significant features ranging from 0.8% to 40.5% depending on the method and dataset. Methods specifically designed for compositional data (ALDEx2, ANCOM-II) produced the most consistent results across studies and agreed best with the intersect of results from different approaches [3]. However, the study also found that the performance of individual tools depended on dataset characteristics such as sample size, sequencing depth, and effect size of community differences.

A more recent 2024 benchmark by Schattenberg et al. introduced a novel simulation framework using in silico spike-ins into real data to create more biologically realistic performance assessments [4]. This study found that only classic statistical methods (linear models, Wilcoxon test, t-test), limma, and fastANCOM properly controlled false discoveries while maintaining relatively high sensitivity. Many popular methods either failed to control false positives or exhibited low sensitivity to detect true positive spike-ins [4].

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Recent benchmarking studies have evaluated methods based on their ability to control false discoveries while maintaining power:

Table 2: Performance Characteristics of Selected Differential Abundance Methods

| Method | False Discovery Rate Control | Sensitivity | Compositional Addressing | Best Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALDEx2 | Consistent control across studies [4] | Lower sensitivity but highly replicable results [3] [18] | Explicit (CLR transformation) | Conservative analysis prioritizing specificity |

| ANCOM-BC | Good control with bias correction [1] | Moderate to high sensitivity | Explicit (Sampling fraction incorporation) | General purpose with FDR control |

| DESeq2/edgeR | Variable, can be inflated in some settings [3] [1] | Generally high sensitivity | Implicit (Robust normalization) | When sparsity assumption is justified |

| Wilcoxon on CLR | Proper control in realistic simulations [4] | High sensitivity with replicable results [18] | Explicit (CLR transformation) | Robust analysis across diverse settings |

| LinDA | Maintains control with strong compositional effects [19] | High power in benchmarks | Explicit (Linear model on CLR) | Correlated microbiome data |

| metagenomeSeq+FTSS | Improved control with group-wise normalization [15] | High statistical power in simulations | Hybrid (Normalization-based) | Scenarios with large compositional bias |

The replication analysis by Pelto et al. (2024) evaluated consistency across 53 taxonomic profiling studies and found that elementary methods—including non-parametric tests (Wilcoxon test) on CLR-transformed data and linear models—provided the most replicable results between random dataset partitions and across separate studies [18]. This suggests a trade-off between methodological sophistication and reproducible outcomes in real-world applications.

Analytical Workflows: From Data to Biological Interpretation

Standardized Differential Analysis Workflow

The following workflow represents a consensus pipeline for differential abundance analysis integrating best practices from multiple benchmarking studies:

Method Selection Decision Framework

Researchers can use the following structured approach to select appropriate methods based on their specific study goals and data characteristics:

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Key Software Implementations

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Differential Abundance Analysis

| Tool/Software | Primary Function | Implementation | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| phyloseq | Data Integration & Visualization | R package | Unifies microbiome data with sample metadata for streamlined analysis |

| ANCOM-BC | Differential Abundance Testing | R package | Incorporates sampling fraction estimation for bias correction |

| DESeq2 | Differential Abundance Testing | R package | Negative binomial model with robust normalization for count data |

| ALDEx2 | Differential Abundance Testing | R package | Monte Carlo sampling of Dirichlet distributions with CLR transformation |

| MaAsLin2 | Differential Abundance Testing | R package | Flexible framework for handling various study designs and covariate structures |

| metagenomeSeq | Differential Abundance Testing | R package | Zero-inflated Gaussian model with cumulative sum scaling normalization |

| LinDA | Differential Abundance Testing | R package | Linear models for correlated microbiome data with compositional bias correction |

| GMPR | Normalization | R package/function | Geometric mean of pairwise ratios for zero-inflated data |

| Wrench | Normalization | R package | Robust normalization for compositional data using reference taxa |

Experimental Protocol for Method Validation

Based on the benchmark by Schattenberg et al. [4], researchers can implement the following protocol for method validation:

Baseline Data Selection: Obtain a reference microbiome dataset from healthy individuals (e.g., the Zeevi WGS dataset used in the benchmark) to serve as a biologically realistic template.

Signal Implantation: Introduce known differential abundance signals through:

- Abundance scaling: Multiply counts in one group by a constant factor (typically 2-10× for realistic effect sizes)

- Prevalence shift: Shuffle a percentage of non-zero entries across groups to mimic differential presence/absence

Method Application: Apply multiple differential abundance methods to the same simulated datasets using standardized parameters:

- For normalization-based methods: Use recommended normalization (TMM for edgeR, RLE for DESeq2, CSS for metagenomeSeq)

- For compositional methods: Follow default parameters for ALDEx2, ANCOM-BC, and LinDA

- Apply independent filtering where appropriate (e.g., 10% prevalence filter)

Performance Assessment: Calculate method-specific false discovery rates (FDR) and sensitivity using the implanted ground truth, applying Benjamini-Hochberg procedure for multiple testing correction with a significance threshold of p < 0.05.

The distinction between absolute and relative abundance changes represents more than a statistical technicality—it fundamentally shapes biological interpretation in microbiome research. Current evidence suggests that no single method universally outperforms others across all dataset types and research scenarios [1] [4]. Methods designed for compositional data (ALDEx2, ANCOM-BC) generally provide more consistent results and better false discovery rate control, while normalization-based methods (DESeq2, edgeR) can approximate absolute abundance changes when the sparsity assumption holds [3] [15]. Recent innovations in group-wise normalization (G-RLE, FTSS) show promise for improving absolute abundance estimation [15], while elementary methods on appropriately transformed data offer surprising replicability advantages for detecting relative abundance changes [18].

For researchers navigating this complex landscape, a consensus approach using multiple complementary methods provides the most robust strategy [3] [4]. The choice between methods targeting absolute versus relative changes should be guided by biological question, study design, and dataset characteristics rather than methodological convenience. As benchmarking efforts continue to evolve with more biologically realistic validation frameworks, the field moves closer to standardized practices that enhance reproducibility and biological insight in microbiome research.

A Landscape of Differential Abundance Methods: From RNA-Seq Adaptations to Compositional-Specific Tools

In the field of high-throughput sequencing analysis, differential abundance (DA) and differential expression (DE) analysis are fundamental for identifying biological features that change between conditions. While originally developed for bulk RNA-Seq data, methods like edgeR, DESeq2, and limma-voom are now extensively applied in microbiome research. However, their performance characteristics can vary significantly based on data type, sample size, and experimental design. This guide objectively compares these three popular methods by synthesizing current benchmarking studies, providing a structured overview of their statistical foundations, performance data, and optimal use cases to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

The adoption of RNA-Seq derived methods for microbiome differential abundance analysis presents a significant challenge: selecting the most appropriate tool without a universal gold standard. Microbiome data are characterized by high dimensionality, compositionality, sparsity (frequent zero counts), and over-dispersion, which can violate the assumptions of many statistical models [20]. Consequently, as demonstrated by a large-scale study in Nature Communications, different DA methods applied to the same 38 datasets identified "drastically different numbers and sets" of significant features [3]. This lack of consensus and reproducibility underscores the critical need for a clear understanding of the strengths and limitations of widely used methods like edgeR, DESeq2, and limma-voom. This guide synthesizes evidence from multiple benchmarking studies to provide a data-driven comparison, enabling more robust and replicable biological interpretations.

Statistical Foundations and Methodologies

The three methods employ distinct statistical strategies to model sequencing count data, which directly influences their performance.

DESeq2 and edgeR both utilize a negative binomial distribution to model count data, a choice designed to handle the over-dispersion common in sequencing datasets [21] [20]. DESeq2 incorporates an empirical Bayes approach to shrink estimated fold changes and dispersion estimates, making it more conservative [21] [22]. edgeR offers flexible dispersion estimation across genes, with options for common, trended, or tagwise dispersion, and provides multiple testing frameworks, including likelihood ratio tests and quasi-likelihood F-tests [21].

In contrast, limma-voom uses a linear modeling framework. Its key innovation is the "voom" transformation, which converts counts to log-counts-per-million (log-CPM) and calculates precision weights to account for the mean-variance relationship in the data. This approach allows the application of empirical Bayes moderation from the linear models microarray analysis tradition, which improves the stability of variance estimates, particularly for studies with small sample sizes [21] [4].

A core difference lies in their handling of compositionality and normalization. DESeq2 uses a median-of-ratios method for normalization, while edgeR typically uses the trimmed mean of M-values (TMM) [21] [20]. Limma-voom also uses the TMM method in its data preprocessing steps before the voom transformation [21].

Table 1: Core Statistical Foundations of edgeR, DESeq2, and limma-voom

| Aspect | limma-voom | DESeq2 | edgeR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Statistical Approach | Linear modeling with empirical Bayes moderation [21] | Negative binomial modeling with empirical Bayes shrinkage [21] | Negative binomial modeling with flexible dispersion estimation [21] |

| Data Transformation & Normalization | voom transformation to log-CPM with precision weights; TMM normalization [21] |

Internal normalization based on geometric mean (median-of-ratios) [21] [20] | TMM normalization by default [21] [20] |

| Variance Handling | Empirical Bayes moderation of variances for small sample sizes [21] | Adaptive shrinkage for dispersion and fold changes [21] | Options for common, trended, or tagwise dispersion [21] |

| Key Testing Procedure | Linear models and moderated t-statistics [21] | Wald test or Likelihood Ratio Test [21] | Likelihood Ratio Test, Quasi-likelihood F-test, or Exact Test [21] |

Figure 1: Comparative analytical workflows for DESeq2, edgeR, and limma-voom. While all begin with count data and filtering, their core normalization, modeling, and testing procedures diverge significantly.

Performance Benchmarking and Experimental Data

Independent benchmarking studies, which use simulated data with a known ground truth or permuted data with no expected differences, reveal critical performance variations.

False Discovery Rate (FDR) Control

Control of the false discovery rate is a fundamental requirement for any statistical method. A benchmark published in Genome Biology found that when analyzing human population RNA-seq samples (with large sample sizes), DESeq2 and edgeR could exhibit "exaggerated false positives," with actual FDRs sometimes exceeding 20% when the target was 5% [23]. The study attributed this to violations of the negative binomial model assumption, often due to outliers in the data. In the same evaluation, limma-voom showed better, though not perfect, FDR control, while non-parametric tests like the Wilcoxon rank-sum test were most robust [23]. Another large-scale benchmarking of 19 methods on microbiome data confirmed that classic methods and limma-voom generally provided proper FDR control at relatively high sensitivity [4].

Sensitivity and Concordance

Sensitivity, or the power to detect true positives, is another key metric. A benchmark using 38 microbiome datasets found that the number of significant features identified by different tools varied widely, with limma-voom (TMMwsp) and Wilcoxon tests often identifying the largest number of significant amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) [3]. However, a higher number of hits is not always better, as it can indicate poor FDR control.

Regarding concordance, a separate analysis showed that while there is a core set of features identified by all three methods, each tool also identifies unique features. DESeq2 and edgeR, given their shared foundation, show higher overlap with each other, while limma-voom can be more "transversal," identifying a substantial number of unique features not found by the other two [22]. This supports the recommendation from [3] to use a consensus approach based on multiple methods to ensure robust biological interpretations.

Table 2: Comparative Performance Across Sample Sizes and Data Types

| Performance Aspect | limma-voom | DESeq2 | edgeR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recommended Sample Size | ≥3 replicates per condition [21] | ≥3 replicates; performs well with more [21] | ≥2 replicates; efficient with small samples [21] |

| FDR Control (Large N) | Moderate to good control [4] [23] | Can be anticonservative (high FDR) in large population studies [23] | Can be anticonservative (high FDR) in large population studies [23] |

| Computational Efficiency | Very efficient, scales well [21] | Can be computationally intensive [21] | Highly efficient, fast processing [21] |

| Best Use Cases | Small sample sizes, multi-factor experiments, time-series data [21] | Moderate to large sample sizes, high biological variability, strong FDR control needed [21] | Very small sample sizes, large datasets, technical replicates [21] |

| Handling of Low Counts | Less adapted to discrete low counts [21] [22] | Conservative with low counts [21] | Particularly shines with low-count genes [21] |

To implement the methodologies discussed, researchers rely on a suite of computational tools and resources.

Table 3: Key Resources for Differential Analysis

| Resource / Solution | Type | Primary Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| benchdamic | Bioconductor R Package | Provides a flexible framework for benchmarking DA methods on user-provided data, evaluating Type I error, concordance, and enrichment. | [24] |

| ALDEx2 | Bioconductor R Package | A compositional data analysis tool that uses a centered log-ratio transformation to address compositionality. | [3] [20] |

| ANCOM-BC | Bioconductor R Package | A compositionally-aware method that uses an additive log-ratio transformation and bias correction. | [4] [24] |

| ZINB-WaVE | Bioconductor R Package | Provides observation weights for zero-inflated data, which can be used to create weighted versions of DESeq2, edgeR, and limma-voom. | [20] [24] |

Integrated Workflow for Robust Differential Abundance Analysis

Given the performance trade-offs, a single-method approach is often insufficient. The following integrated protocol, synthesizing recommendations from multiple studies, enhances the reliability of findings.

Protocol: A Consensus Workflow for DA/DE Analysis

Data Pre-processing and Filtering: Begin with rigorous quality control. Independently filter out low-abundance features (e.g., those with very low counts or present in a small fraction of samples) to reduce noise and the multiple testing burden. A common threshold is to remove features absent in more than 90% of samples [3] [25].

Multi-Tool Analysis: Apply at least two, and preferably all three, methods (DESeq2, edgeR, and limma-voom) to your pre-processed dataset. Use standard normalization and testing procedures for each as defined in their respective documentation.

Generation of a Consensus Result Set: Intersect the lists of significant features (e.g., those with an adjusted p-value < 0.05) obtained from the different tools. Features identified by multiple methods are considered high-confidence candidates. As [3] suggests, the intersect of results from different approaches agrees best with robust biological interpretations.

Exploration of Unique Hits: For features identified by only one method, perform careful manual inspection. Check their abundance profiles and raw counts for potential outliers or spurious patterns that might have driven the significance in one model but not others.

Biological Validation and Interpretation: Finally, use the high-confidence list for downstream functional enrichment analysis and biological interpretation. This consensus approach helps ensure that subsequent experimental validation efforts are focused on the most reliable signals.

Figure 2: A consensus workflow for robust differential analysis. Running multiple methods in parallel and focusing on the intersection of results increases confidence in the final biological findings.

The choice between edgeR, DESeq2, and limma-voom is not a matter of identifying a single "best" tool, but rather of selecting the most appropriate tool for a specific experimental context. DESeq2's conservative nature can be advantageous for studies with moderate to large sample sizes where tight FDR control is desired. edgeR remains a powerful and efficient choice, particularly for experiments with very small sample sizes or when analyzing low-abundance features. limma-voom demonstrates remarkable efficiency and robustness, especially in complex experimental designs and with small sample sizes, though its performance on very sparse microbiome count data requires careful evaluation.

Critically, benchmarking studies consistently show that results can vary dramatically between methods. Therefore, for robust and replicable science, particularly in the complex field of microbiome research, a consensus-based approach that leverages the strengths of multiple tools is highly recommended over reliance on a single method.

High-throughput sequencing technologies, such as 16S rRNA gene sequencing and shotgun metagenomics, have become fundamental for microbial community profiling. However, data generated from these techniques are compositional in nature, meaning they convey relative abundance information rather than absolute counts [6] [3]. This compositionality arises because sequencing instruments constrain the total number of reads per sample, creating a scenario where an increase in one microbial taxon's abundance necessarily leads to apparent decreases in others—a mathematical artifact rather than a biological reality [26] [3]. Ignoring this fundamental property can lead to spurious findings and unacceptably high false-positive rates, sometimes exceeding 30% even with modest sample sizes [26].

Compositional Data Analysis (CoDA) provides a rigorous statistical framework specifically designed to address these challenges by focusing on log-ratio transformations between components [27]. Within this framework, several sophisticated methods have been developed specifically for differential abundance (DA) testing in microbiome studies. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of three prominent CoDA-based approaches: ANCOM (Analysis of Compositions of Microbiomes), ANCOM-BC (ANCOM with Bias Correction), and ALDEx2 (ANOVA-Like Differential Expression 2). Based on extensive benchmarking studies, we evaluate their methodological foundations, performance characteristics, and practical applicability to assist researchers in selecting appropriate tools for biomarker discovery and microbial association studies [6] [4] [3].

Methodological Foundations

Core Principles of CoDA

CoDA methods fundamentally operate on the principle that meaningful information in compositional data resides not in the individual component values but in the ratios between components [27]. All CoDA approaches transform the original composition from the Aitchison simplex (where data are constrained to a constant sum) to real Euclidean space, enabling the application of standard statistical techniques [26]. The two primary log-ratio transformations used are:

- Additive Log-Ratio (ALR) Transformation: This approach converts D-dimensional compositional data to (D-1)-dimensional real space by taking the logarithm of the ratio of each component to a reference component. The choice of reference component is critical and ideally should be a taxon with low variance across samples [3].

- Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) Transformation: This method calculates the logarithm of each component ratio to the geometric mean of all components in the sample, effectively centering the data. This preserves the original dimensionality but creates a singular covariance structure [27] [12].

ANCOM (Analysis of Compositions of Microbiomes)

ANCOM operates on the principle that if a taxon is not differentially abundant, the log-ratios of its abundance to the abundances of other taxa should remain consistent across study groups [28] [3]. The method performs multiple ALR transformations, using each taxon as a reference denominator once, and tests for differential abundance in each transformed dataset. A key output is the W-statistic, which represents the number of times the null hypothesis for a given taxon is rejected across all log-ratio analyses. A higher W value indicates stronger evidence for differential abundance [3] [29]. ANCOM makes minimal distributional assumptions and does not rely on specific parametric forms, enhancing its robustness to various data characteristics [28].

ANCOM-BC (ANCOM with Bias Correction)

ANCOM-BC extends ANCOM by incorporating bias correction terms into a linear regression framework to address differences in sampling fractions across samples [28]. The model can be represented as:

[ E[\log(o{ij})] = \thetai + \betaj + \sum{k=1}^p x{jk}\gammak ]

Where ( \log(o{ij}) ) is the log-observed abundance of taxon i in sample j, ( \thetai ) is the taxon-specific intercept, ( \betaj ) is the sample-specific sampling fraction bias, ( x{jk} ) are covariates, and ( \gamma_k ) are their coefficients [28]. ANCOM-BC provides both bias-corrected abundance estimates and p-values for hypothesis testing, addressing a limitation of the original ANCOM, which only provided the W-statistic without formal significance testing [28] [29]. Recent advancements have led to ANCOM-BC2, which further incorporates taxon-specific bias correction and variance regularization to improve false discovery rate control, especially for small effect sizes [28].

ALDEx2 (ANOVA-Like Differential Expression 2)

ALDEx2 employs a Bayesian Monte Carlo sampling approach based on the Dirichlet distribution to estimate the technical uncertainty inherent in count data generation [6] [27]. The workflow involves: (1) generating posterior probability distributions for the relative abundances via Dirichlet-multinomial sampling; (2) applying the CLR transformation to each Monte Carlo instance; (3) performing standard statistical tests on each transformed instance; and (4) calculating expected p-values and false discovery rates across all instances [27] [12]. Unlike ANCOM and ANCOM-BC, which test for differences in absolute abundance, ALDEx2 is specifically designed to identify differences in relative abundance while accounting for compositionality [6]. This methodological distinction is crucial for appropriate biological interpretation.

Table 1: Core Methodological Characteristics of CoDA Approaches

| Feature | ANCOM | ANCOM-BC | ALDEx2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Transformation | Additive Log-Ratio (ALR) | Additive Log-Ratio (ALR) | Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) |

| Statistical Foundation | Multiple hypothesis testing on all possible log-ratios | Linear model with bias correction | Bayesian Dirichlet Monte Carlo sampling |

| Key Output | W-statistic | Bias-corrected estimates and p-values | Expected p-values and effect sizes |

| Differential Abundance Type | Absolute [6] | Absolute [6] [28] | Relative [6] |

| Handling of Zeros | Pseudo-count addition | Pseudo-count addition [28] | Built-in Bayesian estimation |

| Assumptions | Few taxa are differentially abundant | Sample-specific bias can be estimated | Dirichlet prior is appropriate |

Performance Comparison

False Discovery Rate Control and Sensitivity

Recent benchmarking studies employing realistic simulation frameworks have revealed critical differences in how these methods control error rates. A 2024 benchmark that implanted calibrated signals into real taxonomic profiles found that ANCOM-BC2 (an extension of ANCOM-BC) demonstrated superior false discovery rate (FDR) control, maintaining FDR below the nominal 0.05 level across various sample sizes and effect sizes [4] [28]. In the same evaluation, ALDEx2 showed conservative behavior, effectively controlling false positives but at the cost of reduced sensitivity, particularly with smaller sample sizes [4].

A comprehensive assessment across 38 real datasets revealed that ANCOM and ALDEx2 produce the most consistent results across studies and best agree with the intersection of results from different approaches [3]. When comparing the methods' performance on two large Parkinson's disease gut microbiome datasets, ANCOM-BC showed higher concordance with other methods compared to ALDEx2, suggesting more robust detection of differentially abundant taxa [29].

Table 2: Performance Metrics from Benchmarking Studies

| Method | False Discovery Rate Control | Sensitivity/Power | Consistency Across Datasets | Sample Size Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANCOM | Generally adequate [3] | Moderate [3] | High [3] | Higher (due to W-statistic interpretation) |

| ANCOM-BC | Good with proper regularization [28] | High [28] | High [29] | Moderate to high |

| ANCOM-BC2 | Excellent (maintains nominal level) [4] [28] | High [28] | Not fully evaluated | Works well even with small n [28] |

| ALDEx2 | Excellent (conservative) [4] [27] | Lower, especially with small n [4] [3] | High [3] | Requires larger n for good power [4] |

Computational Performance and Scalability

Computational requirements vary substantially between these approaches. ANCOM's requirement to compute all possible log-ratices results in increased computational time with larger numbers of taxa, making it potentially burdensome for full-resolution amplicon sequence variant (ASV) data [3]. ANCOM-BC and ANCOM-BC2, while computationally efficient for standard analyses, incorporate additional estimation steps for bias correction and variance regularization that increase computational overhead compared to simpler models [28].

ALDEx2's Monte Carlo approach generates multiple posterior instances for statistical testing, which can be computationally intensive for large datasets with many samples and taxa [27] [12]. However, benchmarking studies have noted that all three methods generally complete analyses within practical timeframes for typical microbiome datasets, with computational burden rarely being the primary deciding factor for method selection [6].

Robustness to Data Characteristics

Microbiome data present several analytical challenges, including high sparsity (excess zeros), varying sequencing depths, and heterogeneous variance structures. ALDEx2's Bayesian framework with Dirichlet sampling provides robust handling of zero-inflated data without requiring pseudo-counts, which can sometimes introduce artifacts [27] [12]. In contrast, both ANCOM and ANCOM-BC typically require pseudo-count addition to handle zeros, with ANCOM-BC2 implementing a specific sensitivity filter to mitigate potential false positives arising from this approach [28].

For data with uneven sequencing depth, ANCOM-BC's explicit bias correction term directly addresses this issue by estimating and adjusting for sample-specific sampling fractions [28]. ALDEx2's CLR transformation inherently normalizes for sequencing depth through the geometric mean calculation in the denominator, making it robust to this technical variability [27]. A study comparing methods on 38 datasets found that pre-filtering low-prevalence taxa (e.g., removing features present in <10% of samples) generally improved concordance between all methods, though the effect was most pronounced for ANCOM and ALDEx2 [3] [29].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Benchmarking Framework Design

Recent performance evaluations have employed sophisticated simulation frameworks to overcome the absence of biological ground truth in real microbiome datasets [6] [4]. The most biologically realistic approaches implant calibrated signals into actual taxonomic profiles, creating datasets with known differential abundance patterns while preserving the complex characteristics of real microbiome data [4]. Key parameters varied in these benchmarking studies include:

- Sample size: Typically ranging from 10 to 100+ samples per group

- Percentage of differentially abundant features: Commonly from 5% to 30%

- Effect size: Fold changes between 2 and 10, sometimes incorporating prevalence shifts

- Sequencing depth: Reflecting realistic variations observed in actual studies

- Data source: Both 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing and whole metagenome sequencing data

Performance metrics typically include false discovery rate (proportion of false positives among significant findings), recall (proportion of true positives correctly identified), precision (proportion of true positives among all significant findings), and F1 score (harmonic mean of precision and recall) [6] [4] [30].

Diagram 1: Benchmarking workflow for evaluating differential abundance methods.

Real Data Application Protocol

When applying these methods to real experimental data, researchers should follow a systematic workflow to ensure robust results:

Data Preprocessing: Perform quality control, filtering of low-abundance taxa (typically using prevalence-based filters), and if using ANCOM or ANCOM-BC, add appropriate pseudo-counts [3] [29].

Method-Specific Parameterization:

- For ANCOM: Select appropriate W-statistic threshold (commonly 0.7-0.9) based on the number of taxa [3].

- For ANCOM-BC: Specify the regression formula reflecting the experimental design and enable bias correction [28].

- For ALDEx2: Choose the number of Monte Carlo instances (typically 128-1024) and select appropriate statistical test (t-test, Wilcoxon, or Kruskal-Wallis) [27] [12].

Result Interpretation: For ANCOM, taxa with W-statistics exceeding the critical threshold are considered differentially abundant. For ANCOM-BC and ALDEx2, apply Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate correction to p-values and use a significance threshold of 0.05 [28] [29].

Validation: Employ a consensus approach by comparing results across multiple methods, as taxa identified by multiple approaches generally have higher validation rates [3] [29].

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for CoDA method application to microbiome data.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Software Tools and Packages for CoDA Implementation

| Tool/Package | Primary Function | Implementation | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| ANCOM | Differential abundance testing | R/QIIME 2 | W-statistic, minimal assumptions, no p-values |

| ANCOM-BC | Bias-corrected differential abundance | R | Sample-specific bias correction, p-values |

| ANCOM-BC2 | Multigroup differential abundance | R | Taxon-specific bias correction, variance regularization |

| ALDEx2 | Compositional differential abundance | R | Monte Carlo sampling, CLR transformation, high precision |

| metaSPARSim | Microbiome data simulation | R | Gamma-multivariate hypergeometric model for benchmarking |

| Makarsa | Network-based differential abundance | QIIME 2 | Incorporates microbial interactions via network analysis |

| metaGEENOME | GEE-based differential abundance | R | Accounts for within-subject correlations, longitudinal data |

Experimental Design Considerations

When planning a microbiome study with differential abundance analysis, several key considerations can significantly impact the reliability of results: