Microbiome Differential Abundance Testing: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust Biomarker Discovery

Differential abundance analysis (DAA) is a cornerstone statistical task in microbiome research, essential for identifying microbial biomarkers linked to health and disease.

Microbiome Differential Abundance Testing: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust Biomarker Discovery

Abstract

Differential abundance analysis (DAA) is a cornerstone statistical task in microbiome research, essential for identifying microbial biomarkers linked to health and disease. However, this analysis faces significant challenges including zero-inflation, compositional effects, and high variability, leading to inconsistent results across methods and undermining reproducibility. This article provides researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for navigating DAA, from foundational concepts and methodological comparisons to practical optimization strategies and validation techniques. By synthesizing evidence from recent large-scale benchmarking studies, we offer actionable guidance for selecting appropriate methods, controlling false discoveries, and implementing robust analysis pipelines to yield reliable, biologically interpretable results in biomedical and clinical research.

The Core Challenges in Microbiome Differential Abundance Analysis

In microbiome research, compositional data refers to any dataset where individual measurements represent parts of a constrained whole, thus carrying only relative information. This characteristic is fundamental to data generated by next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies, including 16S rRNA gene sequencing and shotgun metagenomics [1] [2]. The relative abundance of any microbial taxon is intrinsically linked to all other measured taxa within a sample due to the sum constraint, where counts are transformed to proportions that necessarily sum to a fixed total (e.g., 1 or 100%) [3]. This constraint emerges from the sequencing process itself, as sequencers can only process a fixed number of nucleotide fragments, creating a competitive dynamic where an increase in one taxon's observed abundance must decrease the observed abundance of others [1] [2]. Consequently, microbiome data does not provide information about absolute microbial loads in the original environment but only about relative proportions, fundamentally constraining biological interpretation and statistical analysis.

The Fundamental Constraint: From Sequencing Technology to Data Interpretation

The Origin of Compositionality in Sequencing Data

The compositional nature of microbiome data originates from the technical limitations of sequencing platforms. During library preparation, DNA fragments are sequenced to a predetermined depth, resulting in a fixed total number of reads per sample (library size). This process effectively converts unobserved absolute abundances in the biological sample into observed relative abundances in the sequencing output [1] [3]. The sampling fraction—the ratio between observed abundance and true absolute abundance in the original ecosystem—varies substantially between samples due to differences in DNA extraction efficiency, library preparation, and sequencing depth [3]. Since this fraction is unknown and cannot be recovered from sequencing data alone, researchers are limited to analyzing relative relationships between taxa rather than absolute quantities [2] [3].

Mathematical Foundation of Compositional Data

Formally, consider a microbiome sample containing counts for D microbial taxa. The observed counts ( O = [o1, o2, ..., o_D] ) are transformed to relative abundances through closure:

[ pi = \frac{oi}{\sum{j=1}^{D} oj} ]

where ( pi ) represents the relative abundance of taxon i, and ( \sum{i=1}^{D} p_i = 1 ) [2]. This transformation projects the data from D-dimensional real space to a (D-1)-dimensional simplex, altering its geometric properties and invalidating standard statistical methods that assume data exists in unconstrained Euclidean space [1] [2].

Table 1: Key Properties of Compositional Microbiome Data

| Property | Mathematical Description | Practical Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Scale Invariance | ( C(pi) = C(api) ) for any positive constant a | Multiplying all abundances by a constant doesn't change proportions |

| Subcompositional Coherence | Analysis of a subset of taxa gives consistent results with full analysis | Results remain valid when focusing on specific taxonomic groups |

| Permutation Invariance | Results independent of the order of components in the composition | Taxon order in the feature table doesn't affect analysis outcomes |

| Sum Constraint | ( \sum{i=1}^{D} pi = 1 ) | Abundances are mutually dependent; increase in one taxon necessitates decrease in others |

Implications for Differential Abundance Analysis

Analytical Challenges and Spurious Correlations

The compositional nature of microbiome data introduces specific challenges for differential abundance (DA) analysis. First, spurious correlations may arise where taxa appear correlated due to the sum constraint rather than biological relationships [2]. Second, the null bias problem occurs when changes in one taxon's abundance create apparent changes in other taxa, making it difficult to identify true differentially abundant features [4] [3]. This problem is exemplified by a hypothetical scenario where four species with baseline absolute abundances (7, 2, 6, and 10 million cells) change after treatment to (2, 2, 6, and 10 million cells), with only the first species truly differing. Based on compositional data alone, multiple scenarios (including one, three, or four differential taxa) could explain the observed proportions with equal validity [4].

Method-Dependent Results in Practice

Different DA methods handle compositionality with varying approaches, leading to substantially different results. A comprehensive benchmark study evaluating 14 DA methods across 38 real-world microbiome datasets found that these tools identified "drastically different numbers and sets of significant" microbial features [5]. The percentage of significant features identified by each method varied widely, with means ranging from 3.8% to 40.5% across datasets [5]. This method-dependent variability poses significant challenges for biological interpretation and reproducibility, suggesting that researchers should employ a consensus approach based on multiple DA methods to ensure robust conclusions [5].

Table 2: Performance Characteristics of Differential Abundance Methods Addressing Compositionality

| Method | Approach to Compositionality | Reported Strengths | Reported Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ANCOM-BC | Additive log-ratio transformation with bias correction | Good false-positive control | May have reduced power in some settings [4] |

| ALDEx2 | Centered log-ratio transformation with Monte Carlo sampling | Produces consistent results across studies [5] | Lower statistical power to detect differences [5] [4] |

| metagenomeSeq (fitFeatureModel) | Robust normalization (CSS) assuming sparse signals | Improved performance over total sum scaling | Type I error inflation or low power in some settings [4] |

| DACOMP | Reference set-based approach | Explicitly addresses compositional effects | Performance depends on proper reference selection [4] |

| ZicoSeq | Optimized procedure drawing on existing methods | Generally controls false positives across settings | Relatively new method with limited independent validation [4] |

Experimental Protocols for Compositional Data Analysis

Protocol 1: Compositional Data Analysis (CoDA) Workflow

This protocol outlines a standardized approach for analyzing microbiome data within the CoDA framework, utilizing tools available for the R programming language.

Step 1: Data Preparation and Preprocessing

- Begin with an unnormalized count matrix generated from sequence processing pipelines (e.g., DADA2, QIIME2).

- Perform independent filtering to remove low-prevalence features (e.g., taxa present in <10% of samples) to reduce noise [5].

- Avoid rarefying or total sum scaling normalization, as these approaches do not address fundamental compositional effects [1] [2].

Step 2: Zero Handling and Imputation

- Address zero counts using Bayesian-multiplicative replacement methods (e.g.,

zCompositionsR package) [1]. - Alternatively, apply a minimal pseudo-count addition (e.g., 1) if using log-ratio transformations, recognizing this approach is ad hoc and may influence results [3].

Step 3: Log-Ratio Transformation

- Apply centered log-ratio (CLR) transformation using the geometric mean of all taxa as reference:

[ \text{CLR}(xi) = \log \frac{xi}{G(x)} ]

where ( G(x) ) is the geometric mean of all taxa in the sample [1] [2].

- For datasets with clearly defined reference taxa, consider additive log-ratio (ALR) transformation using a specific stable taxon as denominator.

Step 4: Differential Abundance Testing

- Apply compositionally-aware DA methods such as ALDEx2 or ANCOM-BC to the transformed data [5] [4].

- Validate findings using multiple DA methods and report consensus results rather than relying on a single method [5].

Step 5: Interpretation and Visualization

- Interpret results as changes relative to the geometric mean of all taxa (for CLR) or relative to a reference taxon (for ALR).

- Visualize results using compositional biplots to understand relationships between samples and taxa [1] [2].

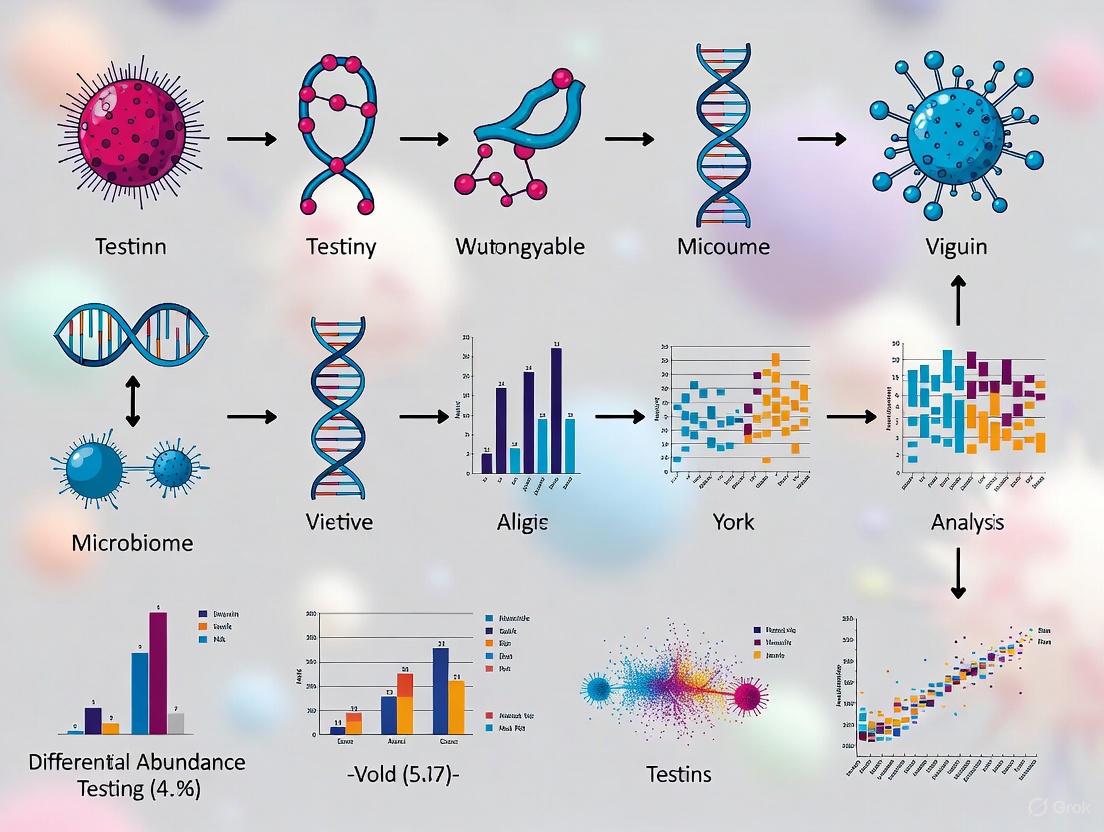

Figure 1: Compositional Data Analysis (CoDA) Workflow. This workflow outlines the key steps for proper analysis of compositional microbiome data, from raw counts to biological interpretation.

Protocol 2: Benchmarking Differential Abundance Methods

This protocol describes an approach for evaluating DA method performance using simulated data with known ground truth, based on recently published benchmarking methodologies [6] [7].

Step 1: Dataset Selection and Simulation

- Select diverse experimental templates representing different environments (e.g., human gut, soil, marine) [6] [7].

- Use simulation tools (e.g.,

metaSPARSim,sparseDOSSA2, orMIDASim) to generate synthetic datasets with known differentially abundant taxa [6]. - Calibrate simulation parameters to real data templates, then introduce controlled effect sizes for specific taxa to establish ground truth [6].

Step 2: Method Application

- Apply a comprehensive set of DA methods, including both compositionally-aware and conventional approaches [6] [4].

- Test methods under varying conditions of sparsity, effect size, and sample size to evaluate robustness [6].

Step 3: Performance Assessment

- Calculate sensitivity and specificity for each method using the known ground truth [6] [7].

- Assess false discovery rate control by analyzing results in scenarios with no true differences [5] [4].

- Evaluate computational efficiency and scalability with large datasets [4].

Step 4: Data Characteristic Analysis

- Calculate key data characteristics (e.g., sparsity, diversity, sample size) for each simulated dataset [6].

- Use multiple regression to identify data characteristics that most strongly influence method performance [6].

Step 5: Recommendation Development

- Develop context-specific recommendations based on data characteristics and research questions [4].

- Identify optimal methods for different data types (e.g., low-biomass vs. high-biomass samples) [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Compositional Microbiome Analysis

| Tool/Package | Primary Function | Application Context | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| zCompositions | Bayesian-multiplicative treatment of zeros | Preprocessing for compositional data | [1] |

| ALDEx2 | Differential abundance via CLR transformation | Microbiome DA analysis with compositionality | [5] [1] |

| ANCOM-BC | Differential abundance with bias correction | Microbiome DA analysis accounting for sampling fraction | [4] |

| propr | Proportionality analysis for relative data | Assessing microbial associations in compositionality framework | [1] |

| metaSPARSim | 16S count data simulation with realistic parameters | Method benchmarking and validation | [6] [7] |

| CoDAhd | Compositional analysis of high-dimensional data | Single-cell RNA-seq in compositional framework | [8] |

| QIIME 2 | End-to-end microbiome analysis pipeline | General microbiome analysis workflow | [2] |

| FAM amine, 5-isomer | FAM amine, 5-isomer|Isomerically Pure Reactive Dye | FAM amine, 5-isomer with a reactive aliphatic amine for labeling. Ideal for creating custom probes via enzymatic transamination. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. | Bench Chemicals |

| FOLFIRI Regimen | FOLFIRI Regiment | The FOLFIRI regimen for cancer research. Contains Irinotecan, 5-Fluorouracil, and Leucovorin. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

Figure 2: Impact of Compositionality on Statistical Inference. The unknown sampling fraction and sum constraint can lead to misleading conclusions if compositionality is not properly addressed in the analysis workflow.

The compositional nature of microbiome data presents a fundamental constraint that researchers must acknowledge and address throughout their analytical workflows. Rather than being a nuisance characteristic that can be normalized away, compositionality represents an intrinsic property of relative abundance data that fundamentally shapes appropriate statistical approaches [1] [2]. The field has moved beyond simply recognizing this constraint to developing sophisticated analytical frameworks, particularly compositional data analysis (CoDA), that properly account for the mathematical properties of relative data [1] [8].

As benchmarking studies consistently demonstrate, the choice of DA method significantly impacts biological interpretations, with different tools identifying largely non-overlapping sets of significant taxa [5] [4]. This methodological dependence underscores the importance of selecting compositionally-aware methods and employing consensus approaches when drawing biological conclusions. Future methodological development should focus on creating more robust approaches that perform well across the diverse range of microbiome data characteristics encountered in practice, while also improving accessibility of compositional methods for applied researchers [6] [4].

By embracing compositional thinking and employing appropriate analytical frameworks, researchers can navigate the constraint of relative abundances to extract meaningful biological insights from microbiome data, advancing our understanding of microbial communities in health, disease, and the environment.

In microbiome research, the accurate interpretation of data is fundamentally challenged by the prevalence of zero values in sequencing counts. These zeros are not a monolithic group; they arise from two distinct sources: true biological absence (a microbe is genuinely not present in the environment) or technical dropouts (a microbe is present but undetected due to limitations in sequencing depth or sampling effort) [9] [10]. This distinction is critical for downstream analyses, particularly differential abundance testing, as misclassifying these zeros can severely distort the true biological signal, leading to both false positives and false negatives [11] [12].

The challenge is exacerbated by the compositional nature of microbiome data, where changes in the abundance of one taxon can artificially appear to influence the abundances of others [13]. Within the context of a broader thesis on differential abundance testing methods, this protocol provides a detailed framework for identifying, handling, and drawing robust conclusions from zero-inflated microbiome data, thereby enhancing the reliability of biomarker discovery and host-microbiome interaction studies.

Core Concepts and Key Distinctions

Defining Zero Types

Table 1: Characteristics of Biological and Technical Zeros

| Feature | Biological Zeros | Technical Zeros |

|---|---|---|

| Cause | Genuine absence of the taxon from its environment [10] | Limited sequencing depth, sampling variation [11] [9] |

| Underlying Abundance | True abundance is zero [10] | True abundance is low but non-zero [11] |

| Pattern in Data | Often consistent across sample groups or conditions [9] | Randomly distributed or correlated with low sequencing depth [11] |

| Imputation Need | Should be preserved as zeros [11] [9] | Can be imputed to recover true signal [11] [9] |

Impact on Differential Abundance Analysis

Failure to properly account for zero inflation compromises differential abundance analysis (DAA). Technical zeros can obscure true associations by reducing the statistical power to detect genuinely differentially abundant taxa. Conversely, misinterpreting technical zeros as biological ones can introduce bias, particularly in methods that rely on log-transformations, which cannot handle zero values [9] [12]. The compositional bias inherent in microbiome data further interacts with zero-inflation, as inaccurately imputed zeros can distort the entire compositional structure, leading to spurious discoveries [13].

Figure 1: A decision workflow for handling zeros in microbiome data, guiding the user to distinguish between biological and technical zeros and apply the appropriate downstream action.

Methodological Approaches and Protocols

This section details specific protocols for distinguishing zero types and performing confounder-adjusted analysis.

Protocol 1: Zero Identification and Imputation with DeepIMB and BMDD

Objective: To accurately identify technical zeros in a taxon count matrix and impute them using a deep learning model that integrates phylogenetic and sample data.

Materials:

- Software: R or Python environment.

- Input Data: A raw taxon count matrix (e.g., OTU or ASV table).

- Auxiliary Data: Sample metadata (e.g., covariates, group labels) and phylogenetic tree (optional but recommended).

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing:

- Normalize the raw count matrix using a method such as Cumulative Sum Scaling (CSS) or Relative Log Expression (RLE).

- Apply a log(x+1) transformation to the normalized data to stabilize variance.

Identification of Non-Biological Zeros (Using DeepIMB Phase 1):

- Fit a Gamma-Normal Mixture Model to the log-transformed abundance data for each taxon [11].

- Model the abundance distribution as a mixture of two components: one representing the low-abundance (likely technical) observations and the other representing the true signal.

- Classify zeros falling within the low-abundance component as "non-biological" and flag them for imputation [11].

Imputation (Using DeepIMB Phase 2):

- Train a Deep Neural Network to predict the true abundance for the flagged zeros.

- The model should use as input:

- The normalized abundances of other taxa.

- Available sample covariates.

- Phylogenetic distance between taxa (if available) [11].

- Replace the technical zeros with the values predicted by the neural network.

Validation:

- Use the imputed matrix for downstream DAA and compare the results (e.g., number of significant taxa, effect sizes) with those from a naive pseudo-count approach. A method like BMDD can be used for benchmarking, as it provides a probabilistic framework for imputation and can account for uncertainty [9] [14].

Protocol 2: Confounder-Adjusted Differential Abundance Testing

Objective: To perform differential abundance testing on zero-handled data while controlling for the effects of confounding variables (e.g., medication, age, batch effects).

Materials:

- Software: R with packages such as

limma,fastANCOM, orMaaslin2. - Input Data: An imputed abundance matrix (from Protocol 1) or a raw count matrix that will be handled by a robust method.

Procedure:

- Model Specification:

- For a linear model-based framework (e.g.,

limma), specify the full model that includes both the primary variable of interest (e.g., disease status) and all potential confounders. - Example model:

Abundance ~ Disease_Status + Age + Medication + Batch

- For a linear model-based framework (e.g.,

Model Fitting and Hypothesis Testing:

- Fit the specified model to the abundance data of each taxon.

- Test the statistical significance of the coefficient for the primary variable (e.g.,

Disease_Status).

Multiple Testing Correction:

- Apply the Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) procedure to the obtained p-values to control the False Discovery Rate (FDR) [12].

Sensitivity Analysis:

- Rerun the analysis with different sets of confounders to assess the stability of the significant results.

- Methods like

fastANCOMare inherently designed to be robust against compositionality and can be a good choice for validation [12].

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Zero-Inflation Analysis

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| DeepIMB [11] | Imputation Method | Identifies/imputes technical zeros via deep learning. | Requires integrated data (taxa, samples, phylogeny). |

| BMDD [9] [14] | Imputation Method | Probabilistic imputation using a bimodal Dirichlet prior. | Captures bimodality; accounts for imputation uncertainty. |

| mbDenoise [10] | Denoising Method | Recovers true abundance via Zero-Inflated Probabilistic PCA. | Uses a low-rank approximation for data redundancy. |

| ZINQ-L [15] | Differential Abundance Test | Zero-inflated quantile test for longitudinal data. | Robust to distributional assumptions; detects tail effects. |

| fastANCOM [12] | Differential Abundance Test | Compositional method for DAA. | Good FDR control and sensitivity in benchmarks [12]. |

| Limma [12] | Differential Abundance Test | Linear models with empirical Bayes moderation. | Requires normalized, log-transformed data; good FDR control [12]. |

| Group-wise Normalization (e.g., FTSS) [13] | Normalization Method | Calculates normalization factors at the group level. | Reduces bias in DAA compared to sample-wise methods [13]. |

Data Presentation and Benchmarking

Realistic benchmarking is essential for selecting the appropriate method.

Table 3: Benchmarking Performance of Selected Methods in Simulations

| Method | Core Approach | Key Performance Metric (vs. Pseudocount) | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| DeepIMB [11] | Gamma-Normal Model + Deep Learning | Lower Mean Squared Error; Higher Pearson Correlation. | High-dimensional data with complex, non-linear patterns. |

| BMDD [9] [14] | BiModal Dirichlet Model + Variational Inference | Better true abundance reconstruction; improves downstream DAA power. | Data with strong bimodal abundance distributions. |

| Group-wise Normalization (FTSS) + MetagenomeSeq [13] | Group-level Scaling | Higher power and better FDR control. | Standard case-control DAA with large compositional bias. |

| Limma / fastANCOM [12] | Linear Model / Compositional Log-Ratio | Proper FDR control and relatively high sensitivity. | General-purpose DAA after careful data preprocessing. |

Figure 2: An integrated analytical workflow for differential abundance analysis, incorporating normalization, zero handling, and confounder adjustment to ensure robust results.

In microbiome research, high-throughput sequencing technologies, including 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing and shotgun metagenomics, have become the foundation of microbial community profiling [16]. A fundamental goal in many microbiome studies is to identify differentially abundant (DA) taxa whose abundance significantly differs between conditions, such as health versus disease [5]. However, the statistical interpretation of microbiome data for DA analysis is severely challenged by two intrinsic properties of the data: high dimensionality and sparsity [6].

High dimensionality refers to the common scenario where the number of measured taxonomic features (P) vastly exceeds the number of biological samples (N), creating a "taxa-to-sample ratio" that is extremely high [16] [17]. This P >> N problem complicates statistical modeling and increases the risk of overfitting. Simultaneously, data sparsity arises from an overabundance of zero counts, which can represent either the true biological absence of a taxon (a structural zero) or its presence at a level undetected due to limited sequencing depth (a sampling zero) [16] [5]. Effectively navigating these intertwined challenges is crucial for robust biomarker discovery and accurate biological interpretation [16] [13].

This Application Note details the experimental and computational protocols essential for conducting reliable differential abundance analysis in the face of high dimensionality and sparsity, providing a structured framework for researchers in microbiome science and drug development.

Quantitative Assessment of the Challenge

The performance of DA methods is heavily influenced by data characteristics. The following table synthesizes findings from large-scale benchmarking studies, summarizing how different DA methods handle the challenges posed by high dimensionality and sparsity.

Table 1: Performance of Differential Abundance Methods in High-Dimensional, Sparse Microbiome Data

| Method Category | Example Methods | Key Strategy | Sensitivity to Sparsity & High D | Reported FDR Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normalization-Based | DESeq2, edgeR [16] [5] | Uses negative binomial models; employs RLE/TMM normalization [16]. | Moderate sensitivity; can be influenced by zero inflation [16] [13]. | Often variable; can be unacceptably high in some benchmarks [5]. |

| Compositional (Ratio-Based) | ALDEx2, ANCOM(-BC) [16] [5] | Applies CLR or ALR transformations to address compositionality [16] [5]. | Generally robust. ALDEx2 noted for lower power but high consistency [5]. | Good to excellent; ANCOM and ALDEx2 often show better FDR control [16] [5]. |

| Non-Parametric / Linear Models | LEfSe, Limma-voom [16] [5] | Uses rank-based tests (LEfSe) or linear models with voom transformation (limma) [16]. | LEfSe can be used on pre-processed data; limma-voom may identify very high numbers of features [5]. | Can be inflated; limma-voom (TMMwsp) sometimes identifies an excessively high proportion of taxa as significant [5]. |

| Mixed/Other Models | MetagenomeSeq, metaGEENOME [16] [13] | Employs zero-inflated Gaussian (MetagenomeSeq) or GEE models with CTF/CLR (metaGEENOME) [16] [13]. | Designed to handle sparsity. metaGEENOME reports high sensitivity and specificity [16]. | Varies; MetagenomeSeq with FTSS normalization shows improved FDR control [13]. |

Experimental Protocols for Robust DA Analysis

Protocol 1: A Framework for Managing High-Dimensional Data

This protocol outlines a procedure for analyzing microbiome data with a high taxa-to-sample ratio.

Primary Workflow Objective: To mitigate the risks of overfitting and false discoveries in high-dimensional datasets by integrating robust normalization, transformation, and modeling steps.

Materials:

- Software: R statistical environment.

- Data Input: A raw count table (features x samples) and associated sample metadata.

Procedure:

- Pre-processing and Independent Filtering: Apply prevalence and abundance filters to remove rare taxa. This filtering must be independent of the test statistic to avoid false positives. A common practice is to retain taxa present in at least 10% of samples within a dataset [5].

- Normalization (Addressing Compositionality): Calculate normalization factors to account for varying library sizes and compositional bias. The choice of method is critical.

- The CTF (Counts adjusted with Trimmed Mean of M-values) normalization method demonstrates high performance. It involves calculating log2 fold changes (M values) and average expression counts (A values) between samples, followed by double-trimming (typically 30% of M values and 5% of A values) to compute a robust weighted mean [16].

- Alternatively, newer group-wise normalization methods like Group-wise RLE (G-RLE) and Fold Truncated Sum Scaling (FTSS) leverage group-level summary statistics and have been shown to improve FDR control in challenging scenarios [13].

- Data Transformation: Transform the normalized counts to overcome the constraints of the compositional simplex.

- Apply the Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) Transformation. For a sample vector x, the CLR is computed as:

CLR(x) = {log(xâ‚ / G(x)), ..., log(xâ‚™ / G(x))} = {log(xâ‚) - log(G(x)), ..., log(xâ‚™) - log(G(x))}where G(x) is the geometric mean of all taxa in the sample. The CLR transformation avoids the need for an arbitrary reference taxon required by the Additive Log-Ratio (ALR) transformation, providing more robust results [16].

- Apply the Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) Transformation. For a sample vector x, the CLR is computed as:

- Statistical Modeling with Correlation Structure: Model the transformed data using techniques that account for high dimensionality and potential within-subject correlations (e.g., in longitudinal designs).

- Employ a Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) model with a compound symmetry (exchangeable) working correlation structure. GEE provides consistent parameter estimates even if the correlation structure is misspecified and is suitable for non-normally distributed data [16].

- The integrated metaGEENOME framework (CTF + CLR + GEE) has been benchmarked to show high sensitivity and specificity while controlling the FDR [16].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of this protocol.

Protocol 2: A Multi-Part Strategy for Handling Sparse Data with Excess Zeros

This protocol provides a detailed method for testing differential abundance when data is characterized by a high proportion of zero counts.

Primary Workflow Objective: To accurately discern the biological signal in sparse data by applying different statistical tests based on the observed data structure.

Materials:

- Software: SAS or other statistical software capable of running two-part tests, Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, and Chi-square or Barnard's tests.

- Data Input: A filtered and normalized count or relative abundance table.

Procedure:

- Data Stratification: For each taxon, categorize the observed abundance data into a binary part (presence/absence) and a continuous part (non-zero abundance values).

- Test Selection Logic:

- If a taxon is present (non-zero) in some samples and absent (zero) in others and the non-zero values are highly skewed or non-normal, apply a two-part test [18]. This test simultaneously evaluates differences in both the prevalence (presence/absence) and the conditional abundance (mean value when present).

- If a taxon is present in all or nearly all samples within the groups being compared, a standard Wilcoxon rank-sum test can be applied to the abundance values [18].

- If the primary difference for a taxon is in its prevalence (i.e., it is present in one group but completely absent in the other), a Chi-square test or Barnard's test can be used on the binary presence/absence data [18].

- Implementation and Interpretation: The multi-part strategy selects the most suitable test automatically based on the data structure for each taxon. This approach has been shown to maintain a good Type I error rate and allows for nuanced biological interpretation—for example, distinguishing whether a taxon's association is driven by its colonization (presence) or its proliferation (abundance) [18].

The logical flow for selecting the appropriate test within this strategy is outlined below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Computational Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents and Tools for Microbiome DA Analysis

| Item Name | Function / Application | Relevant Protocol |

|---|---|---|

R Package: metaGEENOME |

An integrated framework implementing the CTF normalization, CLR transformation, and GEE modeling for robust DA analysis in cross-sectional and longitudinal studies [16]. | Protocol 1 |

R Package: CRAmed |

A conditional randomization test for high-dimensional mediation analysis in sparse microbiome data, decomposing effects into presence-absence and abundance components [19]. | Specialized Mediation Analysis |

R Package: ALDEx2 |

A compositional data analysis tool that uses a CLR transformation and Bayesian methods to infer differential abundance, known for robust FDR control [5]. | Protocol 1 |

| Normalization Method: FTSS | Fold Truncated Sum Scaling, a group-wise normalization method that, when used with MetagenomeSeq, achieves high statistical power and maintains FDR control [13]. | Protocol 1 |

| SAS Macro (Multi-part) | A script to perform the multi-part strategy analysis, which selects statistical tests (two-part, Wilcoxon, Chi-square) based on the data structure of each taxon [18]. | Protocol 2 |

Simulation Tool: sparseDOSSA2 |

A tool for generating realistic synthetic microbiome data with a known ground truth, used for benchmarking DA methods and validating findings [6]. | Benchmarking & Validation |

| Foscarbidopa | Foscarbidopa | |

| Gly-PEG3-amine | Gly-PEG3-amine, MF:C12H27N3O4, MW:277.36 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Sequencing depth, defined as the number of DNA reads generated per sample, represents a fundamental parameter in microbiome study design that directly influences detection sensitivity and analytical outcomes. In differential abundance analysis (DAA), appropriate sequencing depth is critical for generating biologically meaningful results while avoiding both wasteful oversampling and underpowered undersampling. Microbiome data possess unique characteristics including compositional structure, high dimensionality, sparsity, and zero-inflation that complicate statistical interpretation and amplify the impact of depth variation [20]. These characteristics mean that observed abundances are relative rather than absolute, as each taxon's read count depends on the counts of all other taxa in the sample [5].

The relationship between sequencing depth and detection capability follows a nonlinear pattern, where initial increases in depth yield substantial gains in feature detection that eventually plateau. Understanding this relationship is essential for optimizing resource allocation while maintaining statistical validity in microbiome studies. This protocol examines how sequencing depth variation impacts detection sensitivity and normalization effectiveness, providing frameworks for designing robust microbiome studies within the broader context of differential abundance testing methodology.

The Impact of Sequencing Depth on Microbial Detection

Empirical Evidence from Experimental Studies

Multiple studies have systematically quantified how sequencing depth affects feature detection in microbiome analyses. In a comprehensive investigation of bovine fecal samples, researchers compared three sequencing depths (D1: 117 million reads, D0.5: 59 million reads, D0.25: 26 million reads) and observed that while relative proportions of major phyla remained fairly consistent, the absolute number of detected taxa increased significantly with greater depth [21]. Specifically, the number of reads assigned to antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) and microbial taxa demonstrated a strong positive correlation with sequencing intensity, with D0.5 depth deemed sufficient for characterizing both the microbiome and resistome in this system.

Similar patterns emerged in environmental microbiome research, where analysis of aquatic samples from Sundarbans mangrove regions revealed significantly different observed Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) when comparing total reads versus subsampled datasets (25k, 50k, and 75k reads) [22]. The Bray-Curtis dissimilarity analysis demonstrated notable differences in microbiome composition across depth groups, with each group exhibiting slightly different core microbiome structures. Importantly, variation in sequencing depth affected predictions of environmental drivers associated with microbiome composition, highlighting how depth influences ecological interpretation.

For strain-level resolution, even greater depth requirements emerge. Research on human gut microbiome single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) analysis demonstrated that conventional shallow-depth sequencing fails to support systematic metagenomic SNP discovery [23]. Ultra-deep sequencing (ranging from 437-786 GB) detected significantly more functionally important SNPs, enabling reliable downstream analyses and novel discoveries that would be missed with standard sequencing approaches.

Quantitative Depth-Detection Relationships

Table 1: Sequencing Depth Impact on Feature Detection Across Studies

| Study Type | Depth Levels Compared | Key Detection Metrics | Optimal Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bovine Fecal Microbiome [21] | 26M, 59M, 117M reads | Taxon assignment, ARG detection | ~59M reads |

| Aquatic Environmental Samples [22] | 25k, 50k, 75k reads | ASV diversity, composition stability | >50k reads |

| Human Gut Strain-Level [23] | Shallow vs. ultra-deep (437-786GB) | SNP discovery, strain resolution | Ultra-deep required |

| General 16S rRNA [22] | Variable depths | Taxon richness, β-diversity | Study-dependent |

The relationship between sequencing depth and detection follows a saturating curve pattern, where initial depth increases yield substantial gains in feature detection that gradually plateau. The point of diminishing returns varies by ecosystem complexity and evenness, with low-biomass or high-diversity communities typically requiring greater depth for comprehensive characterization.

Normalization Methods for Addressing Depth Variation

The Normalization Framework in Compositional Data

Normalization methods attempt to correct for technical variation in sequencing depth to enable valid biological comparisons. These methods can be broadly categorized into four groups: (1) ecology-based approaches like rarefying; (2) traditional normalization techniques; (3) RNA-seq-derived methods; and (4) microbiome-specific methods that address compositionality, sparsity, and zero-inflation [20]. The fundamental challenge stems from the compositional nature of microbiome data, where counts are constrained to sum to the total reads per sample (library size), making observed abundances relative rather than absolute [13].

The compositional bias problem can be formally characterized through statistical modeling. Under a multinomial sampling framework, the maximum likelihood estimator of the true log fold change (( \beta_j )) becomes biased by an additive term (( \delta )) that reflects the ratio of average total absolute abundance between comparison groups [13]:

[ \text{plim}{n \to \infty} \hat{\beta}j = \beta_j + \delta ]

This bias term does not depend on the specific taxon but rather represents a group-level difference in microbial content, motivating group-wise normalization approaches.

Normalization Method Comparison

Table 2: Normalization Methods for Microbiome Sequencing Data

| Method | Principle | Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Sum Scaling (TSS) | Divides counts by total reads | General purpose | Fails to address compositionality |

| Rarefying | Subsampling to even depth | Diversity analyses, β-diversity | Data loss, power reduction |

| Relative Log Expression (RLE) | Median-based fold changes | DESeq2, general DAA | Assumes most taxa non-DA |

| Trimmed Mean of M-values (TMM) | Weighted trim of fold changes | edgeR, cross-study | Assumes most taxa non-DA |

| Cumulative Sum Scaling (CSS) | Truncated sum based on quantile | MetagenomeSeq | Designed for zero-inflation |

| Center Log-Ratio (CLR) | Log-ratio with geometric mean | ALDEx2, compositional | Handles compositionality |

| Group-wise RLE (G-RLE) | RLE applied at group level | Novel frameworks | Redures group bias |

| Fold Truncated Sum Scaling (FTSS) | Group-level reference taxa | Novel frameworks | Addresses compositionality |

Emerging Group-wise Normalization Approaches

Recent methodological advances have reconceptualized normalization as a group-level rather than sample-level task. The group-wise framework includes two novel approaches: group-wise relative log expression (G-RLE) and fold-truncated sum scaling (FTSS) [13]. These methods leverage group-level summary statistics of the subpopulations being compared, explicitly acknowledging that compositional bias reflects differences at the group level rather than individual sample level.

In simulation studies, G-RLE and FTSS demonstrate higher statistical power for identifying differentially abundant taxa compared to existing methods while maintaining false discovery rate control in challenging scenarios where traditional methods suffer [13]. The most robust performance was obtained using FTSS normalization with the MetagenomeSeq DAA method, providing a solid mathematical foundation for improved rigor and reproducibility in microbiome research.

Experimental Protocols for Depth Optimization

Protocol 1: Determining Optimal Sequencing Depth

Purpose: To establish depth requirements for a specific microbiome study while balancing cost and detection sensitivity.

Materials:

- High-quality extracted DNA from representative samples

- Standard sequencing platform (Illumina recommended)

- Computational resources for bioinformatic analysis

- Quality control tools (FastQC, Trimmomatic)

- Taxonomic profilers (Kraken, MetaPhlAn2)

Procedure:

- Pilot Sequencing: Select 3-5 representative samples for deep sequencing (≥50 million reads per sample for 16S; ≥100 million for shotgun metagenomics).

- Bioinformatic Processing:

- Perform quality filtering and adapter removal.

- Conduct taxonomic assignment using standardized databases.

- Generate count tables for downstream analysis.

- Depth Gradient Analysis:

- Use downsampling tools (BBMap, Seqtk) to create subsets simulating lower depths (e.g., 10%, 25%, 50%, 75% of original reads).

- At each depth level, calculate alpha diversity (Shannon, Chao1) and beta diversity (Bray-Curtis, UniFrac).

- Record the number of taxa detected at various taxonomic levels.

- Saturation Point Determination:

- Plot depth versus feature detection curves.

- Identify the point where additional reads yield minimal new features (<5% increase per 10% read increase).

- Consider functional goals (community profiling vs. rare variant detection).

Expected Outcomes: A depth-detection relationship plot specific to your study system, informing appropriate sequencing depth for the full study.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Normalization Method Performance

Purpose: To select the most appropriate normalization method for a specific dataset and research question.

Materials:

- Raw count table from microbiome sequencing

- Sample metadata with group assignments

- R statistical environment with appropriate packages (DESeq2, edgeR, metagenomeSeq, ALDEx2)

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing:

- Apply consistent prevalence filtering (e.g., retain features present in >10% of samples).

- Create multiple normalized datasets using different methods (TSS, CSS, TMM, RLE, CLR, G-RLE if available).

- Method Evaluation:

- For each normalized dataset, perform beta-diversity analysis (PCoA with Bray-Curtis).

- Assess sample clustering according to biological groups versus technical batches.

- Apply differential abundance testing using consistent statistical thresholds.

- Compare the number and identity of significant taxa across methods.

- Benchmarking Against Validation:

- If available validation data exists (spike-ins, qPCR), compute correlation between normalized abundances and ground truth.

- For simulated data, calculate false discovery rates and sensitivity.

- Stability Assessment:

- Apply slight perturbations to data (subsampling) and observe result stability.

- Evaluate consistency of biological interpretations across methods.

Expected Outcomes: Recommendation for optimal normalization approach based on data characteristics and research objectives, with documentation of method-specific differences in results.

Visualization of Relationships and Workflows

Figure 1: Relationship between sequencing depth, data characteristics, normalization approaches, and differential abundance analysis outcomes. Group-wise and compositional methods generally provide more robust performance compared to traditional sample-level approaches.

Figure 2: Workflow for determining optimal sequencing depth through pilot sequencing and computational downsampling, ensuring adequate detection power while maximizing resource efficiency.

Table 3: Essential Resources for Sequencing Depth and Normalization Experiments

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Wet Lab Reagents | Tiangen Fecal Genomic DNA Extraction Kit | High-quality DNA extraction with Gram-positive/Gram-negative balance |

| Illumina NovaSeq 6000 | High-throughput sequencing platform | |

| Quality control reagents (agarose gel, NanoDrop) | DNA quality and quantity assessment | |

| Bioinformatic Tools | FastQC, Trimmomatic | Read quality control and adapter trimming |

| BBMap, Seqtk | Computational downsampling for depth simulation | |

| Kraken, MetaPhlAn2 | Taxonomic profiling and assignment | |

| Statistical Packages | DESeq2, edgeR | Normalization and differential abundance testing |

| ALDEx2, ANCOM-BC | Compositional data analysis | |

| metaGEENOME, benchdamic | Comparative method evaluation | |

| Reference Databases | RefSeq, GTDB | Taxonomic classification standards |

| Custom kraken databases (bvfpa) | Comprehensive bacterial, viral, fungal, protozoan, archaeal coverage |

Sequencing depth fundamentally shapes microbiome study outcomes by determining detection sensitivity and influencing normalization effectiveness. The evidence indicates that depth requirements are context-dependent, with strain-level analyses demanding ultra-deep sequencing [23], while standard community profiling may achieve saturation at moderate depths [21]. Crucially, normalization methods perform differently across depth gradients, with emerging group-wise approaches (G-RLE, FTSS) showing particular promise for maintaining false discovery rate control in challenging scenarios [13].

For implementation, we recommend: (1) conducting pilot studies with depth gradients to establish project-specific requirements; (2) adopting a consensus approach using multiple normalization methods to verify robust findings [5]; (3) selecting depth based on specific research goals (community structure versus rare variant detection); and (4) transparently reporting depth metrics and normalization approaches to enable cross-study comparisons. As sequencing technologies evolve and costs decrease, the field must maintain rigorous standards for depth optimization and normalization to ensure biological discoveries reflect true signals rather than technical artifacts.

Differential abundance (DA) testing represents a fundamental statistical procedure in microbiome research for identifying microorganisms whose abundances differ significantly between conditions. Despite over a decade of methodological development, no consensus exists regarding optimal DA approaches, and different methods frequently yield discordant results when applied to the same datasets. This application note examines the core statistical and experimental challenges underlying this methodological inconsistency, benchmarks current tool performance across diverse realistic simulations, and provides structured protocols for robust biomarker discovery. We demonstrate that inherent data characteristics—including compositionality, sparsity, and variable effect sizes—interact differently with various statistical frameworks, preventing any single method from achieving universal robustness.

Microbiome differential abundance analysis aims to identify microbial taxa that systematically vary between experimental conditions or patient groups, serving as a cornerstone for developing microbiological biomarkers and therapeutic targets [4]. The statistical interpretation of microbiome sequencing data, however, is challenged by several inherent properties that distinguish it from other genomic data types and complicate analytical approaches.

Three interconnected characteristics fundamentally undermine universal methodological solutions. First, compositionality arises because sequencing data provide only relative abundance information rather than absolute microbial counts [4] [24]. This means that an observed increase in one taxon's relative abundance may reflect either its actual expansion or the decline of other community members. Without additional information (such as total microbial load), this fundamental ambiguity cannot be completely resolved mathematically [4]. Second, zero inflation presents a substantial challenge, with typical microbiome datasets containing over 70% zero values [4]. These zeros may represent either true biological absences (structural zeros) or undetected presences due to limited sequencing depth (sampling zeros), requiring different statistical treatments. Third, high variability in microbial abundances spans several orders of magnitude, creating substantial heteroscedasticity that violates assumptions of many parametric tests [4].

These data characteristics collectively ensure that no single statistical model optimally addresses all analytical scenarios, necessitating a nuanced understanding of how different methods interact with specific data properties.

Methodological Approaches and Their Limitations

Categories of Differential Abundance Methods

DA methods have evolved along three primary conceptual lineages, each addressing core data challenges through different statistical frameworks:

Table 1: Major Categories of Differential Abundance Testing Methods

| Category | Representative Methods | Core Approach | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Statistical Tests | Wilcoxon, t-test, linear models | Apply standard statistical tests to transformed data | Often poor false discovery control with sparse, compositional data [12] [24] |

| RNA-Seq Adapted Methods | DESeq2, edgeR, limma-voom | Model overdispersed count data using negative binomial distributions | Assume independence between features; sensitive to compositionality [4] [24] |

| Composition-Aware Methods | ANCOM, ALDEx2, ANCOM-BC | Use log-ratio transformations to address compositionality | May have reduced sensitivity; require sparsity assumptions [4] [24] |

| Zero-Inflated Models | metagenomeSeq, ZIBB | Explicitly model structural and sampling zeros separately | Computational complexity; potential overfitting [4] |

Empirical Evidence of Method Inconsistency

Large-scale benchmarking studies demonstrate alarming inconsistencies across DA methods. A comprehensive evaluation of 14 DA tools across 38 real 16S rRNA gene datasets revealed that different methods identify drastically different numbers and sets of significant taxa [24]. For instance, in unfiltered analyses, the percentage of features identified as significantly differentially abundant ranged from 0.8% to 40.5% across methods, with similar variability observed after prevalence filtering [24].

The disagreement between methods is not merely quantitative but extends to the specific taxa identified. When applied to the same datasets, the overlap between significant features identified by different tools is often remarkably small [24]. This lack of consensus fundamentally undermines biological interpretation, as conclusions become dependent on analytical choices rather than biological reality.

Core Statistical Challenges Preventing Universal Solutions

The Compositionality Problem

Compositional effects present the most fundamental statistical challenge in DA analysis. Because microbiome data provide only relative information (proportions), observed changes in one taxon necessarily affect all other taxa' apparent abundances [4]. Consider a hypothetical community with four species whose baseline absolute abundances are 7, 2, 6, and 10 million cells per unit volume. After an intervention, the abundances become 2, 2, 6, and 10 million cells, where only the first species shows a true change. The resulting compositions would be (28%, 8%, 24%, 40%) versus (10%, 10%, 30%, 50%) [4]. Based solely on this compositional data, multiple scenarios could explain the observations with equal mathematical validity: one, three, or even four differential taxa [4]. Most composition-aware methods resolve this ambiguity by assuming signal sparsity (few truly differential taxa), but this assumption may not hold in all biological contexts.

Sparsity and Zero Inflation

The preponderance of zeros in microbiome data (typically >70% of values) creates substantial statistical challenges [4]. The diagram below illustrates how different methodological approaches address this zero-inflation problem:

The appropriate treatment of zeros depends on their biological origin, which is generally unknown a priori. Methods that assume all zeros arise from sampling (e.g., DESeq2, edgeR) may perform poorly when structural zeros are common, while zero-inflated models risk overfitting when sampling zeros predominate [4].

Effect Size Heterogeneity

Real microbiome alterations manifest through diverse abundance patterns that no single statistical model optimally captures. Empirical analyses of established disease-microbiome associations reveal two predominant alteration patterns: abundance scaling (fold changes in detected abundances) and prevalence shifts (changes in detection frequency) [12]. These effect types present different statistical challenges, with certain methods more sensitive to abundance changes and others better detecting prevalence shifts.

Table 2: Method Performance Across Effect Types and Data Characteristics

| Method | Abundance Scaling | Prevalence Shifts | High Sparsity | Large Effect Sizes | Small Sample Sizes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALDEx2 | Moderate | Low | Good | Moderate | Poor |

| ANCOM-II | Moderate | Moderate | Good | Good | Moderate |

| DESeq2 | Good | Poor | Poor | Good | Moderate |

| LEfSe | Moderate | Good | Moderate | Good | Poor |

| limma-voom | Good | Poor | Poor | Good | Good |

| MaAsLin2 | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Good | Moderate |

| Wilcoxon | Moderate | Good | Moderate | Good | Poor |

Benchmarking Frameworks and Performance Realities

Simulation Approaches for Realistic Benchmarking

Accurate method evaluation requires simulated data with known ground truth that faithfully preserves real data characteristics. Traditional parametric simulations often generate unrealistic data that fails to capture complex biological structures [12]. More recent approaches have developed more biologically realistic benchmarking frameworks:

Signal implantation introduces calibrated abundance and prevalence shifts into real taxonomic profiles, preserving inherent data structures while incorporating known differential features [12]. This approach maintains realistic feature variance distributions, sparsity patterns, and mean-variance relationships that parametric simulations often distort [12].

Template-based simulation uses parameters estimated from real experimental datasets across diverse environments (human gut, soil, marine, etc.) to generate synthetic data that mirrors the characteristic of real-world studies [6] [25]. This approach covers a broad spectrum of data characteristics, with sample sizes ranging from 24-2,296 and feature counts from 327-59,736 across different templates [6].

Protocol: Realistic Benchmarking Using Signal Implantation

Objective: Generate biologically realistic simulated data with known differential features for method evaluation.

Materials:

- Baseline microbiome dataset from healthy population (e.g., Zeevi WGS dataset)

- Statistical computing environment (R/Python)

- Signal implantation code (custom implementation or available benchmarks)

Procedure:

- Data Preparation:

- Select a representative baseline dataset with sufficient sample size

- Apply standard quality control and normalization procedures

- Randomly assign samples to two experimental groups

Effect Size Calibration:

- Determine target effect sizes based on real disease studies (e.g., colorectal cancer, Crohn's disease)

- For abundance shifts: Use scaling factors typically <10-fold based on empirical observations [12]

- For prevalence shifts: Calculate differences in detection frequency observed in meta-analyses

Signal Implantation:

- Randomly select target features for differential abundance

- For abundance shifts: Multiply counts in the test group by scaling factor

- For prevalence shifts: Shuffle a percentage of non-zero entries across groups

- Apply both effect types simultaneously for mixed scenarios

Validation:

- Verify preservation of original data characteristics (variance, sparsity)

- Confirm machine learning classifiers cannot distinguish simulated from real data

- Ensure principal coordinate analysis shows overlapping distributions

This protocol generates data that closely mirrors real experimental conditions while incorporating known ground truth for method evaluation.

Performance Realities Across Data Characteristics

Benchmarking studies consistently reveal that method performance depends critically on data characteristics that vary across studies. A comprehensive evaluation of 19 DA methods using realistic simulations found that only classic statistical methods (linear models, t-test, Wilcoxon), limma, and fastANCOM properly controlled false discoveries while maintaining reasonable sensitivity [12]. However, even these better-performing methods showed substantial variability across different data conditions.

The performance of DA methods systematically depends on three key data properties:

Sample Size: Methods vary substantially in their statistical power with limited samples, with some tools exhibiting adequate false discovery control only at larger sample sizes [6] [25].

Effect Size: Both the magnitude and type of abundance differences (abundance scaling vs. prevalence shifts) interact with method performance, with different tools optimal for different effect profiles [12].

Community Sparsity: The degree of zero inflation significantly impacts method performance, with composition-aware methods generally more robust to high sparsity levels [6] [4].

Experimental Considerations and Best Practices

Table 3: Essential Resources for Robust Microbiome DA Analysis

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation Tools | metaSPARSim, sparseDOSSA2, MIDASim | Generate realistic synthetic data with known ground truth for method validation [6] [25] |

| Benchmarking Frameworks | Custom signal implantation, previous benchmark datasets | Evaluate method performance under controlled conditions [12] |

| Data Repositories | SRA, GEO, PRIDE, Metabolomics Workbench | Public data access for method development and validation [26] |

| Reporting Standards | GSC MIxS, STREAMS guidelines | Standardized metadata and reporting for reproducibility [26] |

| Experimental Controls | Mock communities, negative extraction controls | Monitor technical variability and contamination [27] [28] |

| Analysis Pipelines | QIIME 2, DADA2, DEBLUR | Standardized data processing for comparable results [29] |

Protocol: Consensus Approach for Robust Biomarker Discovery

Objective: Identify differentially abundant taxa using a method-agnostic framework that maximizes reproducibility.

Materials:

- Processed microbiome count table with metadata

- Multiple DA methods (minimum 3-4 representing different approaches)

- Computational resources for parallel analysis

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing:

- Apply prevalence filtering (e.g., retain features in >10% of samples) [24]

- Consider rarefaction only if analyzing methods requiring even sampling depth

- Apply appropriate normalization for each method (TMM, CSS, CLR)

Parallel Differential Analysis:

- Select methods from different conceptual frameworks (e.g., ALDEx2, DESeq2, ANCOM-BC, MaAsLin2)

- Apply each method independently with recommended settings

- Record p-values and effect sizes for all features

Results Integration:

- Identify features significant by multiple methods (consensus features)

- Prioritize features based on agreement across frameworks

- For discordant results, examine data characteristics that might explain methodological differences

Biological Validation:

- Focus interpretation on consensus features

- Contextualize findings considering effect sizes and prevalence patterns

- Acknowledge methodological limitations in biological interpretations

This consensus approach mitigates the risk of method-specific artifacts and provides more robust biological insights.

The absence of a universally optimal differential abundance method stems from fundamental tensions between statistical modeling approaches and the complex, interdependent nature of microbiome data. Compositionality ensures that no analysis can completely resolve absolute abundance changes from relative measurements without additional experimental data. The diverse nature of true biological effects (abundance scaling, prevalence shifts, and their combinations) means that different statistical frameworks naturally exhibit differential sensitivity across biological scenarios.

Moving forward, the field requires enhanced benchmarking frameworks that better capture real data characteristics, continued method development that explicitly addresses the multidimensional nature of microbiome effects, and standardized reporting practices that increase methodological transparency. Most immediately, researchers should adopt consensus-based approaches that leverage multiple complementary methods rather than relying on any single tool, acknowledging that robust biomarker discovery requires methodological triangulation rather than universal solutions.

A Practical Guide to Differential Abundance Methods and Their Implementation

The application of count-based models like edgeR and DESeq2 represents a fundamental methodology for identifying differentially abundant taxa in microbiome studies. These models, originally developed for RNA-Seq data, are now routinely applied to high-throughput sequencing data from microbial communities, including 16S rRNA amplicon and shotgun metagenomic studies [20] [4]. They employ a negative binomial distribution to appropriately model the over-dispersed nature of sequencing count data, where variance exceeds the mean [5] [4]. This statistical framework enables robust detection of microbial taxa whose abundances significantly differ between experimental conditions, disease states, or treatment groups—a core objective in microbiome research with implications for biomarker discovery and therapeutic development [30] [4].

Adapting these methods for microbiome data presents distinct challenges that must be addressed for valid biological inference. Microbiome data exhibits three primary characteristics that complicate analysis: compositionality (data representing relative proportions rather than absolute abundances), zero-inflation (a high percentage of zero counts due to both biological absence and undersampling), and variable library sizes (sequencing depth) across samples [20] [4] [31]. These characteristics can lead to false discoveries if not properly accounted for in the analytical framework. Specifically, compositional effects can create spurious correlations where changes in one taxon's abundance artificially appear to affect others [4] [31]. Consequently, the direct application of edgeR and DESeq2 without modifications tailored to microbiome data can produce biased results, necessitating specific normalization strategies and methodological adaptations [32] [20] [31].

Normalization Strategies for Microbiome Data

Normalization is a critical preprocessing step that accounts for variable library sizes across samples, reducing technical artifacts before differential abundance testing. For microbiome data, this step is particularly crucial due to both compositionality and zero-inflation. The table below summarizes the primary normalization methods used with count-based models for microbiome data:

Table 1: Normalization Methods for Microbiome Count Data

| Method | Underlying Principle | Key Strengths | Key Limitations | Compatible Models |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values) | Trims extreme log-fold changes and A-values (average abundance) to calculate scaling factors [33]. | Robust to differentially abundant features and outliers; widely adopted [33] [34]. | Performance can degrade with extreme zero-inflation [32] [4]. | edgeR, limma-voom |

| RLE (Relative Log Expression) | Uses median ratio of sample counts to geometric mean of all samples [32] [33]. | Effective for RNA-Seq data with low zero-inflation. | Fails with no common taxa across samples; unstable with high zero-inflation [32]. | DESeq2 |

| GMPR (Geometric Mean of Pairwise Ratios) | Calculates size factors from geometric mean of pairwise sample ratios using shared non-zero features [32]. | Specifically designed for zero-inflated data; utilizes more data than RLE [32]. | Computationally intensive for very large sample sizes. | edgeR, DESeq2, general use |

| TSS (Total Sum Scaling) | Scales counts by total library size (converts to proportions) [32]. | Simple and intuitive calculation. | Highly sensitive to outliers and compositionality [32] [31]. | General use (not recommended) |

| CSS (Cumulative Sum Scaling) | Scales by cumulative sum of counts up to a data-driven percentile [20] [4]. | Data-driven approach for microbiome data. | Percentile determination may fail with high variability [32]. | metagenomeSeq |

The Geometric Mean of Pairwise Ratios (GMPR) method was specifically developed to address the high zero-inflation characteristic of microbiome data [32]. Unlike RLE, which fails when no taxa are shared across all samples, GMPR performs pairwise comparisons between samples, using only taxa that are non-zero in both samples for each comparison. The median ratio from each pairwise comparison is then synthesized via a geometric mean to produce a robust size factor for each sample [32]. This approach effectively utilizes more information from sparse microbiome data and has demonstrated superior performance in simulations and real data analyses compared to methods adapted directly from RNA-Seq [32].

For researchers using edgeR, the TMMwsp (TMM with singleton pairing) method provides a valuable variant specifically designed to improve stability with data containing a high proportion of zeros. This method pairs singleton positive counts between libraries in decreasing order of size before applying a modified TMM procedure, enhancing performance for sparse data [33].

Experimental Protocols for Differential Abundance Analysis

edgeR Protocol for Microbiome Data

The following protocol outlines the step-by-step procedure for conducting differential abundance analysis of microbiome data using edgeR:

Table 2: edgeR Protocol for Microbiome Differential Abundance Analysis

| Step | Procedure | Key Considerations | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Data Input | Create DGEList object containing count matrix and group information. | Ensure counts are raw integers, not normalized or transformed values. | Statistical models assume raw count distribution properties [33] [34]. |

| 2. Filtering | Remove low-abundance features using filterByExpr() or prevalence-based filtering. |

Prevalent filtering (e.g., 10% across samples) can reduce multiple testing burden [5]. | Increases power by focusing on informative taxa; reduces false discoveries [5] [33]. |

| 3. Normalization | Calculate normalization factors using calcNormFactors() with method="TMM" or method="TMMwsp" for zero-inflated data. |

For data with high zero-inflation, consider GMPR normalization instead [32]. | Accounts for compositionality and variable sampling efficiency [33] [4]. |

| 4. Dispersion Estimation | Estimate common, trended, and tagwise dispersions using estimateDisp(). |

Design matrix must be specified to account for experimental conditions. | Models biological variability between samples and groups [33] [34]. |

| 5. Differential Testing | Perform quasi-likelihood F-tests using glmQLFit() and glmQLFTest(). |

Alternative: exact tests for simple designs, negative binomial models for complex designs. | Identifies significantly differentially abundant taxa while controlling false discoveries [33]. |

| 6. Result Interpretation | Extract results with topTags(), apply FDR correction (e.g., BH method). |

Consider log-fold change thresholds alongside statistical significance. | Balances statistical significance with biological relevance [33] [34]. |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps in the edgeR protocol for microbiome data analysis:

DESeq2 Protocol for Microbiome Data

The DESeq2 package provides an alternative framework for differential abundance analysis with specific considerations for microbiome data:

Table 3: DESeq2 Protocol for Microbiome Differential Abundance Analysis

| Step | Procedure | Key Considerations | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Object Creation | Create DESeqDataSetFromMatrix() with raw counts and experimental design. | For microbiome data, consider using GMPR size factors instead of standard RLE. | Standard RLE normalization fails with no common taxa [32] [35]. |

| 2. Normalization | Apply size factors using estimateSizeFactors(). |

For severe zero-inflation, supply externally calculated GMPR size factors. | Addresses library size variation and compositionality [32] [35]. |

| 3. Dispersion Estimation | Run estimateDispersions() to model biological variability. |

For small sample sizes, use "local" or "parametric" sharing modes. | Accounts for overdispersion in count data [35]. |

| 4. Statistical Testing | Perform Wald tests or LRT using DESeq() function. |

For small sample sizes, consider the LRT instead of Wald test. | Identifies differentially abundant taxa [35]. |

| 5. Results Extraction | Extract results with results() function, applying independent filtering. |

Use lfcThreshold parameter for fold change thresholds. |

Balances sensitivity and specificity [35]. |

For both protocols, it is critical to visually diagnose data quality both before and after analysis. Visualization techniques such as PCA plots, heatmaps of sample-to-sample distances, and dispersion plots should be employed to identify potential outliers, batch effects, or inadequate model assumptions.

Performance Evaluation and Method Comparisons

Comprehensive benchmarking studies have evaluated the performance of count-based models alongside other differential abundance methods across diverse microbiome datasets. The table below summarizes key findings from large-scale evaluations:

Table 4: Performance Comparison of Differential Abundance Methods on Microbiome Data

| Method | False Discovery Rate Control | Statistical Power | Sensitivity to Compositionality | Robustness to Zero Inflation | Recommended Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| edgeR | Variable; can be inflated in some settings [5] [4]. | Generally high power [4]. | Moderate sensitivity without proper normalization [4]. | Moderate; improved with TMMwsp or GMPR [32] [33]. | Large effect sizes, balanced designs |

| DESeq2 | Can be inflated with large sample sizes or uneven library sizes [31]. | High for small sample sizes [31]. | Moderate sensitivity without proper normalization [4]. | Moderate; improved with alternative normalization [32]. | Small sample sizes (<20/group) |

| ANCOM-BC | Good FDR control [30] [4]. | Moderate to high [4]. | Specifically addresses compositionality [4]. | Good with proper zero handling [4]. | When compositional effects are a major concern |

| ALDEx2 | Conservative FDR control [5] [4]. | Lower than count-based methods [5]. | Specifically addresses compositionality via CLR [5]. | Good with proper zero handling [5]. | When false positive control is prioritized |

| limma-voom | Variable; can be inflated in some settings [5]. | High [5]. | Moderate sensitivity [30]. | Moderate [30]. | Large datasets with continuous outcomes |

A critical finding across multiple evaluations is that no single method consistently outperforms all others across all data characteristics and experimental conditions [5] [4]. The performance of edgeR and DESeq2 depends heavily on appropriate normalization specific to microbiome data characteristics and the specific experimental context. Methods that explicitly address compositional effects (such as ANCOM-BC and ALDEx2) generally demonstrate improved false discovery rate control, though sometimes at the cost of reduced statistical power [4]. The number of features identified as differentially abundant can vary dramatically between methods, with limma-voom and edgeR often identifying the largest numbers of significant taxa in empirical comparisons [5].

Successful implementation of count-based models for microbiome differential abundance analysis requires both computational tools and methodological considerations. The following toolkit summarizes essential components:

Table 5: Essential Computational Tools for Microbiome Differential Abundance Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Notes | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| edgeR | Differential abundance analysis using negative binomial models. | Use TMMwsp for sparse data; consider incorporating GMPR normalization. | Bioconductor |

| DESeq2 | Differential abundance analysis using negative binomial models. | Supply external size factors for zero-inflated data instead of standard RLE. | Bioconductor |

| GMPR | Size factor calculation for zero-inflated sequencing data. | Particularly valuable for datasets with no common taxa across all samples. | GitHub: jchen1981/GMPR |

| ANCOM-BC | Compositionally aware differential abundance analysis. | Useful as a complementary approach to validate findings from count-based models. | CRAN |

| ALDEx2 | Compositionally aware differential abundance analysis using CLR transformation. | Provides a conservative approach with good FDR control. | Bioconductor |

| phyloseq | Data organization and visualization for microbiome data. | Facilitates data preprocessing, filtering, and visualization. | Bioconductor |

| MicrobiomeStat | Comprehensive suite for statistical analysis of microbiome data. | Includes implementations of various normalization and differential abundance methods. | R package |

The following diagram illustrates the decision pathway for selecting appropriate differential abundance methods based on study characteristics:

Based on current benchmarking studies and methodological evaluations, researchers should adopt several best practices when applying count-based models to microbiome data. First, normalization selection should be data-adaptive, with GMPR or similar zero-inflated normalization methods preferred for datasets with high sparsity (>70% zeros) or no taxa shared across all samples [32]. Second, a consensus approach that applies multiple differential abundance methods (e.g., edgeR/DESeq2 alongside compositionally aware methods like ANCOM-BC) provides more robust biological conclusions than reliance on a single method [5] [4]. Third, result interpretation should consider both statistical significance and effect size (log-fold changes) while recognizing the compositional nature of the data [4].

The adaptation of count-based models for microbiome data continues to evolve, with recent developments including group-wise normalization frameworks [36] and integrated approaches that combine robust normalization with advanced modeling techniques [30]. These advancements promise to enhance the rigor and reproducibility of microbiome biomarker discovery, ultimately strengthening the translation of microbiome research into clinical and therapeutic applications.

Microbiome sequencing data is inherently compositional, meaning that the data represents relative proportions rather than absolute abundances. This compositionality arises because sequencing instruments measure counts that are constrained to a constant sum (the total number of sequences per sample), where an increase in one taxon's abundance necessarily leads to apparent decreases in others [31] [37]. This fundamental characteristic poses significant challenges for differential abundance analysis, as standard statistical tests that ignore compositionality can produce unacceptably high false discovery rates [31] [37].