Microbiome Network Inference: A Comprehensive Guide to Methods, Applications, and Validation

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the rapidly evolving field of microbiome network inference, a key exploratory technique for understanding complex microbial interactions and their implications for human health...

Microbiome Network Inference: A Comprehensive Guide to Methods, Applications, and Validation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the rapidly evolving field of microbiome network inference, a key exploratory technique for understanding complex microbial interactions and their implications for human health and disease. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers foundational concepts, from defining microbial interactions and the challenges of compositional data to the biological interpretation of network edges. The review critically assesses a spectrum of methodological approaches, including correlation-based methods, conditional dependence models like SPIEC-EASI and OneNet, and the practical workflow for network construction. It further addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization challenges, such as data preprocessing, handling rare taxa, and mitigating environmental confounders. Finally, the article evaluates advanced validation frameworks and comparative studies, highlighting emerging standards like cross-validation and consensus methods to ensure biological reproducibility and robust network inference for therapeutic discovery.

The Blueprint of Microbial Societies: Foundations of Network Inference

In microbiome research, accurately defining microbial interactions is fundamental to understanding community assembly, stability, and function. The field has progressively evolved from analyzing simple correlation patterns to inferring conditional dependence, which more accurately represents direct ecological interactions by accounting for the compositional nature of sequencing data and controlling for confounding effects of other community members [1] [2]. This shift is critical for distinguishing direct microbial interactions from indirect associations mediated through other taxa, enabling more biologically meaningful insights into community dynamics [3]. Traditional correlation-based approaches often produce spurious results due to data compositionality, where relative abundances sum to a constant, thereby necessitating more sophisticated statistical frameworks that can address these inherent data constraints [1] [4].

The advancement of network inference methods has transformed our ability to decipher complex microbial relationships from high-dimensional microbiome datasets. These methods now incorporate specialized approaches to handle compositional data, sparsity constraints, and longitudinal dynamics, providing powerful tools for predicting community behavior and identifying keystone species [5] [6]. This progression from correlation to conditional dependence represents a paradigm shift in microbial ecology, enabling researchers to move beyond descriptive associations toward mechanistic understanding of microbial community dynamics.

Methodological Evolution: From Correlation to Conditional Dependence

Limitations of Correlation-Based Approaches

Correlation-based methods, including Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients, were among the first computational approaches used to infer microbial interactions from abundance data. These methods estimate pairwise associations without accounting for the influence of other taxa in the community, thus conflating direct and indirect interactions [3]. A significant limitation arises from the compositional nature of microbiome data, where relative abundances are constrained to a constant sum (e.g., 100% in proportional data). This property introduces spurious correlations that do not reflect true biological interactions [1] [2]. Furthermore, correlation methods are particularly prone to detecting false associations among low-abundance taxa and require subjective threshold selection to define significant interactions, potentially leading to misinterpretations of network structures [4].

Foundations of Conditional Dependence Methods

Conditional dependence methods address these limitations by estimating interactions between pairs of taxa while controlling for the effects of all other taxa in the community [3]. This approach effectively separates direct interactions from indirect associations mediated through other community members. The mathematical foundation of these methods often relies on partial correlations or inverse covariance estimation, which provide a more accurate representation of direct microbial relationships by accounting for the multivariate nature of microbial communities [1] [2]. Under conditional dependence frameworks, a zero entry in the inverse covariance matrix indicates conditional independence between corresponding taxa given the rest of the community, thereby reflecting true direct interactions [1].

Table 1: Comparison of Microbial Interaction Inference Methods

| Method Type | Statistical Foundation | Handles Compositionality | Distinguishes Direct vs. Indirect Interactions | Example Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation-Based | Pearson/Spearman correlation | No | No | Conventional co-occurrence networks |

| Conditional Dependence | Partial correlation/Inverse covariance | Yes | Yes | gCoda, SPIEC-EASI, LUPINE |

| Longitudinal Network Inference | PLS regression/PCA | Yes | Yes | LUPINE |

| Machine Learning-Based | Graph neural networks | Varies | Varies | Graph neural network models |

Advanced Conditional Dependence Frameworks

gCoda: Compositional Data Analysis

The gCoda method represents a significant advancement in conditional dependence inference by explicitly addressing the compositional nature of microbiome data through a logistic normal distribution model [1]. This approach assumes that observed compositional data are generated from latent absolute abundances that follow a multivariate normal distribution in log space. The method incorporates a sparse inverse covariance estimation with penalized maximum likelihood to address the high dimensionality of microbiome data, where the number of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) often exceeds sample size [1].

The key innovation of gCoda lies in its transformation of the interaction inference problem into estimating the structure of the inverse covariance matrix (precision matrix) of the latent variables. The optimization problem is solved using a Majorization-Minimization algorithm that guarantees decrease of the objective function until reaching a local optimum [1]. Simulation studies demonstrate that gCoda outperforms existing methods like SPIEC-EASI in edge recovery of inverse covariance for compositional data across various scenarios, providing more accurate inference of direct microbial interactions [1].

LUPINE: Longitudinal Network Inference

For longitudinal microbiome studies, LUPINE represents a novel approach that leverages conditional independence and low-dimensional data representation to infer microbial networks across time points [3]. This method incorporates information from all previous time points, enabling capture of dynamic microbial interactions that evolve over time. LUPINE utilizes projection to latent structures regression to maximize covariance between current and preceding time point datasets, effectively modeling the temporal dynamics of taxon interactions [3].

The methodology includes three variants: single time point modeling using principal component analysis, two time point modeling using PLS regression, and multiple time point modeling using generalized PLS for multiple data blocks [3]. This flexibility allows researchers to adapt the method based on their experimental design and specific research questions. LUPINE has been validated across multiple case studies including mouse and human studies with varying intervention types and time courses, demonstrating its robustness for different experimental designs [3].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Network Inference Methods

| Method | Data Type | Computational Approach | Key Advantages | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| gCoda | Cross-sectional | Penalized maximum likelihood with MM algorithm | Explicitly models compositional data; handles sparsity | Outperforms SPIEC-EASI in edge recovery under various scenarios [1] |

| LUPINE | Longitudinal | PLS regression with sequential modeling | Incorporates temporal dynamics; suitable for small sample sizes | Robust performance across multiple case studies; identifies relevant taxa [3] |

| Graph Neural Networks | Longitudinal | Graph convolution and temporal convolution layers | Predicts future community dynamics; captures relational dependencies | Accurately predicts species dynamics up to 10 time points ahead (2-4 months) [6] |

| RMT-Based Networks | Cross-sectional | Random Matrix Theory | Identifies keystone taxa; minimizes subjective thresholds | Reveals structural differences not detected by diversity metrics [4] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing gCoda for Microbial Interaction Inference

Purpose: To infer direct microbial interactions from compositional microbiome data using the gCoda framework.

Reagents and Materials:

- Normalized relative abundance data (e.g., proportions, centered log-ratio transformed)

- Computational environment with R installed

- gCoda package (available under LGPL v3)

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing:

- Normalize raw sequence counts to relative abundances summing to 1

- Apply centered log-ratio transformation to address compositionality

- Standardize variables to zero mean and unit variance

Parameter Tuning:

- Set tuning parameters (λ1, λ2) to balance model fitting and sparsity

- Use cross-validation to select optimal penalty parameters

- Initialize Ω as a positive definite matrix

Model Optimization:

- Implement the Majorization-Minimization algorithm to solve the optimization problem

- Iterate until objective function convergence

- Ensure positive definiteness of the estimated Ω matrix

Network Construction:

- Extract non-zero entries from the estimated inverse covariance matrix

- Apply significance thresholding to identify robust interactions

- Visualize resulting network using appropriate software (e.g., Cytoscape)

Interpretation: Non-zero entries in the estimated Ω matrix represent direct conditional dependencies between microbial taxa after accounting for compositionality and controlling for all other taxa in the community [1].

Protocol 2: Longitudinal Network Inference with LUPINE

Purpose: To infer microbial networks across multiple time points using the LUPINE framework.

Reagents and Materials:

- Longitudinal microbiome abundance data across multiple time points

- R statistical environment

- LUPINE package (publicly available)

Procedure:

- Data Structuring:

- Organize abundance data into time-point specific matrices (X_t)

- Account for library size variations between samples

- Group samples by experimental conditions if applicable

Model Selection:

- For single time point analysis: Use PCA-based approach (LUPINE_single)

- For two time points: Implement PLS regression maximizing covariance between consecutive time points

- For multiple time points: Apply generalized PLS for multiple data blocks

Partial Correlation Estimation:

- For taxa pair (i,j), regress against one-dimensional approximation of other taxa (X^-(i,j))

- Use first principal component of control taxa to avoid high-dimensionality issues

- Calculate partial correlations from regression residuals

Network Significance Testing:

- Apply permutation-based significance thresholds

- Control for multiple testing using false discovery rate correction

- Compare networks across time points using appropriate metrics

Interpretation: Significant edges in LUPINE networks represent conditional dependencies between taxa that persist across specified time intervals, providing insights into stable microbial interactions within dynamic communities [3].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item | Function/Application | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Power Soil DNA Isolation Kit | DNA extraction from complex microbial samples | Effective lysis of diverse microbial cells; suitable for fecal and environmental samples [5] [4] |

| 16S rRNA gene primers | Amplification of bacterial and archaeal target regions | Target V1-V3 (Bac9F/Ba515Rmod1) or other hypervariable regions; design impacts taxonomic resolution [4] |

| Illumina MiSeq platform | High-throughput sequencing of amplicon libraries | 2×250 bp paired-end sequencing; suitable for microbiome profiling studies [5] [4] |

| QIIME2 pipeline | Processing and analysis of raw sequencing data | Version 2019.10 or later; includes DADA2 for quality control and ASV generation [4] |

| SILVA database | Taxonomic classification of sequence variants | Version 132 or later; provides comprehensive rRNA reference database [4] |

| R statistical environment | Implementation of network inference methods | Essential for running gCoda, LUPINE, and other compositional data analysis tools [1] [3] |

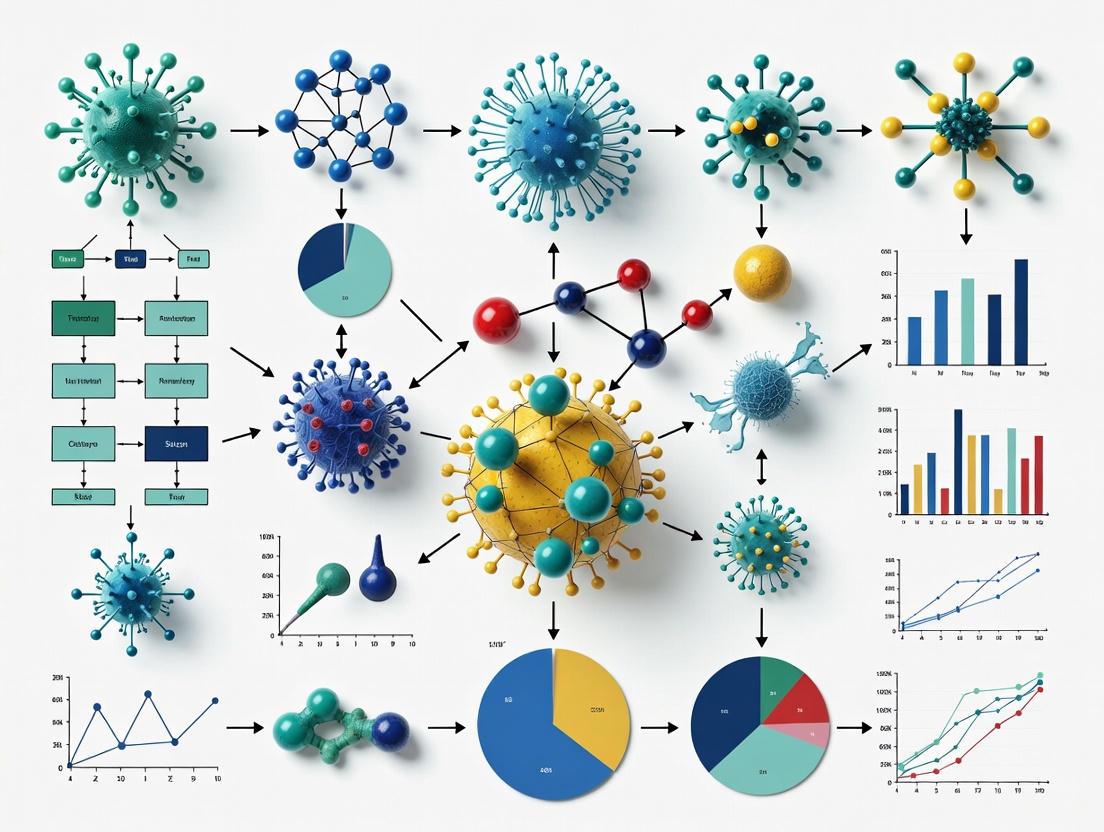

Workflow Visualization

Microbial Network Inference Workflow: This diagram illustrates the sequential process for inferring microbial interactions from raw sequencing data to biological interpretation, highlighting the critical decision point between correlation and conditional dependence approaches.

Applications and Case Studies

Environmental Gradient Analysis

A comprehensive study of bacterial, archaeal, and microeukaryotic communities across subtropical coastal waters demonstrated the utility of conditional dependence networks for revealing biogeographic patterns [5]. Researchers collected surface water samples from 99 stations across inshore, nearshore, and offshore zones in the East China Sea, analyzing co-occurrence networks for each domain. The study revealed that network complexity was highest for bacteria, while modularity was highest for archaeal networks [5]. Notably, all three domains showed consistent biogeographic patterns across environmental gradients, with the highest intensity of microbial co-occurrence in nearshore zones experiencing intermediate terrestrial impacts. Archaea, particularly Thaumarchaeota Marine Group I, occupied central positions in inter-domain networks, serving as hubs connecting different network modules across environmental gradients [5].

Predicting Community Dynamics

Graph neural network models have demonstrated remarkable capability in predicting future microbial community dynamics using historical relative abundance data [6]. A study of 24 wastewater treatment plants involving 4,709 samples collected over 3-8 years showed that these models could accurately predict species dynamics up to 10 time points ahead (2-4 months), and sometimes up to 20 time points (8 months) [6]. The approach utilized graph convolution layers to learn interaction strengths between taxa, temporal convolution layers to extract temporal features, and fully connected neural networks to predict future relative abundances. When tested on the human gut microbiome, the method maintained predictive accuracy, demonstrating generalizability across microbial ecosystems [6].

Host-Microbe-Drug Interactions

Advanced computational frameworks like DHCLHAM utilize dual-hypergraph contrastive learning with hierarchical attention mechanisms to predict microbe-drug interactions [7] [8]. This approach integrates multiple similarity metrics, including functional similarity of medicinal chemical attributes and microbial genomes, to construct comprehensive interaction networks. The model employs a dual-hypergraph structure with K-Nearest Neighbors and K-means Optimizer algorithms, combined with contrastive learning to enhance representation of heterogeneous hypergraph space [7]. On benchmark datasets, this approach achieved AUC and AUPR scores of 98.61% and 98.33%, respectively, significantly outperforming existing methods and providing valuable insights for personalized medicine and drug development [7] [8].

Advanced Visualization Techniques

Advanced Hypergraph Learning Framework: This diagram illustrates the sophisticated DHCLHAM pipeline for predicting microbe-drug interactions, showcasing the integration of hypergraph structures with contrastive learning and attention mechanisms for enhanced prediction accuracy.

In microbial ecology, networks provide a powerful framework for moving beyond simple taxonomic lists to understanding the complex web of interactions within microbial communities. These networks are mathematically represented as graphs, where nodes (vertices) represent microbial taxa (e.g., species, genera), and edges (links) represent the statistical associations or inferred ecological interactions between them [9]. The structure of these networks—which nodes are connected and how strongly—reveals fundamental ecological organization that governs community stability, function, and its impact on the host environment.

Constructing these networks from microbiome sequencing data presents unique computational challenges. The data are inherently compositional, meaning that sequencing technologies capture relative abundances rather than absolute cell counts, making correlations difficult to interpret [9]. Additionally, microbiome data is often sparse (containing many zero values) and high-dimensional, with far more microbial taxa than samples, requiring specialized statistical methods to distinguish robust biological signals from noise [10] [9]. Despite these challenges, network analysis has revealed crucial insights, demonstrating that the contributions of taxa to microbial associations are disproportionate to their abundances, and that rarer taxa play an integral role in shaping community dynamics [9].

Conceptual Framework: Nodes and Edges

Nodes (Vertices)

In a microbial association network, each node corresponds to a defined biological entity, typically a microbial taxon. The specific taxonomic level (e.g., species, genus, phylum) is a critical decision in the network inference process. While species-level networks offer high resolution, the analytical choice depends on the sequencing depth, reference database completeness, and the biological question at hand. Nodes can possess attributes that provide additional layers of information for interpretation. These attributes often include:

- Taxonomic lineage: The full classification of the taxon (Kingdom, Phylum, Class, etc.).

- Mean relative abundance: The average proportion of the taxon across all samples.

- Prevalence: The percentage of samples in which the taxon is detected.

In network visualization tools, these node attributes can be mapped to visual properties such as size (e.g., proportional to abundance), color (e.g., by phylum), or shape to create intuitive and information-rich graphical representations [11].

Edges (Links)

Edges represent the statistical associations or inferred ecological interactions between pairs of nodes. These associations can be broadly categorized into two types, each with distinct biological interpretations:

- Positive associations (often visualized as green or blue edges) suggest potential mutualistic, cooperative, or cross-feeding relationships where taxa co-occur more frequently than expected by chance.

- Negative associations (often visualized as red edges) suggest potential competitive or antagonistic relationships where the presence of one taxon is linked to the absence of another.

Crucially, the method used to infer the network determines what an edge represents. The two primary classes of methods are:

- Correlation-based methods: These infer edges based on simple co-occurrence or co-abundance patterns. While computationally simpler, they are highly susceptible to indirect correlations, where a correlation between Taxa A and B is driven by a third, unobserved factor Taxon C [10] [9].

- Conditional dependence-based methods: These more advanced methods, such as those based on Gaussian Graphical Models (GGMs), infer edges based on conditional independence. An edge between Taxa A and B exists if they are correlated after accounting for the abundances of all other taxa in the network [10]. This helps to eliminate spurious edges and is better at approximating direct ecological interactions.

Table 1: Interpretation of Network Edges Based on Inference Method.

| Inference Method Class | What an Edge Represents | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation-Based | Total dependency (Co-occurrence) | Computational simplicity | Prone to indirect, spurious correlations |

| Conditional Dependence-Based | Direct interaction (Conditional dependence) | Filters out indirect effects | Higher computational cost; more complex implementation |

Computational Protocols for Network Inference

Protocol 1: Inferring a Co-occurrence Network with SPIEC-EASI

SPIEC-EASI (Sparse Inverse Covariance Estimation for Ecological Association Inference) is a widely adopted method that tackles compositionality and sparsity to infer more reliable, sparse microbial networks [9]. The following protocol outlines its application.

1. Data Preprocessing and Normalization

- Input: An

n x pmicrobial abundance matrix (n samples, p taxa). - Quality Filtering: Remove taxa that are present in fewer than a specified percentage of samples (e.g., 10-20%) to reduce noise from rare species.

- Normalization: Apply a variance-stabilizing transformation. While SPIEC-EASI has built-in handling for compositionality, a common preparatory step is to perform a Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) transformation on the filtered data [10]. This transformation maps the compositional data from the simplex to a real-space Euclidean geometry, making it more amenable to correlation-based methods.

2. Network Inference via Neighborhood Selection

- Method Selection: Within the SPIEC-EASI framework, select the MB (Meinshausen-Bühlmann) approach for stability selection [10].

- Model Fitting: The method estimates the sparse inverse covariance matrix (precision matrix) of the data. A non-zero entry in this matrix indicates a conditional dependence between two taxa, forming an edge in the network.

- Stability Selection: This resampling procedure is used to tune the regularization parameter

λ, which controls network sparsity. The data is subsampled multiple times, and networks are inferred for a range ofλvalues. The finalλ*is chosen based on the stability of the resulting edges across subsamples [10].

3. Network Construction and Edge Selection

- Edge Weights: The non-zero entries in the final selected precision matrix provide the weights for the edges in the network.

- Thresholding: Only edges that persist across a high proportion of resampling iterations (e.g., >95%) are retained, ensuring that the final network consists of robust, reproducible associations.

Figure 1: SPIEC-EASI Network Inference Workflow.

Protocol 2: Building a Consensus Network with OneNet

Given that different inference methods can yield vastly different networks from the same dataset, consensus methods like OneNet have been developed to produce more robust and reliable networks [10].

1. Multi-Method Inference

- Input: The preprocessed abundance matrix from Protocol 1, Step 1.

- Parallel Inference: Apply seven different GGM-based inference methods (Magma, SpiecEasi, gCoda, PLNnetwork, EMtree, SPRING, ZiLN) to the same dataset. Each method will output a network with a set of edges and associated scores (e.g., selection probability or penalty level) [10].

2. Edge Selection Frequency Calculation

- For each of the seven methods, calculate a sequence of selection frequency values for every possible edge. This involves a resampling procedure where the network is inferred on multiple subsamples of the data for different penalty parameters [10].

- The selection frequency for an edge

eat a parameterλ_kis:f_e^k = (1/B) * Σ_{b=1 to B} 1{e ∈ G_b,k}, whereBis the number of subsamples and1{}is the indicator function [10].

3. Consensus Network Assembly

- The selection frequencies for each edge from all seven methods are combined.

- A threshold is applied to the combined selection frequencies. Only edges that exceed this threshold (i.e., edges that are consistently selected by multiple methods across resampling iterations) are included in the final consensus network [10]. This approach generally results in sparser networks with higher precision than any single method.

Figure 2: OneNet Consensus Network Workflow.

Protocol 3: Analyzing Longitudinal Data with LUPINE

For time-series microbiome data, LUPINE (LongitUdinal modelling with Partial least squares regression for NEtwork inference) is a specialized method that leverages information from all past time points to capture dynamic microbial interactions [12].

1. Data Structuring

- Input: A longitudinal abundance matrix where samples are collected from the same subjects over multiple time points.

- Formatting: Structure the data to model the abundance of each taxon at time

tas a function of the abundances of all other taxa at previous time point(s)t-1(ort-n).

2. Model Fitting

- LUPINE uses Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression, a technique suited for datasets with a large number of correlated predictor variables (i.e., many taxa) and a small sample size [12].

- For each taxon, a PLS model is built to predict its abundance at time

tbased on the microbial community composition at timet-1.

3. Network Interpretation

- The regression coefficients from the PLS models are interpreted as the direction and strength of influence that one taxon has on the future abundance of another.

- These directed influences form a longitudinal network, providing insights into successional patterns, microbial disturbances, and the temporal stability of interactions [12].

Essential Tools and Reagents for Microbial Network Analysis

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit for Microbial Network Inference.

| Tool/Reagent Category | Example | Function and Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Network Inference Software (R/Python) | SpiecEasi [9], OneNet [10], LUPINE [12] | Core statistical environment for executing inference algorithms. OneNet combines 7 methods for robust consensus. LUPINE is designed for longitudinal data. |

| Visualization & Analysis Platform | Cytoscape [11], NetCoMi [10] | Cytoscape provides advanced network visualization and exploration. NetCoMi offers an all-in-one R platform for inference and comparison. |

| Data Preprocessing Tool | Kraken2/Bracken [9], Trimmomatic [9] | Tools for taxonomic assignment and abundance quantification (Kraken2/Bracken) and read quality control (Trimmomatic). |

| Normalization Technique | Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) [10], GMPR [10] | Compositional data transformations. CLR is common for many methods, while GMPR (Geometric Mean of Pairwise Ratios) is used for specific models like PLNnetwork. |

| Stability Assessment Method | Stability Selection (StARS) [10] | A resampling-based procedure for robust tuning of sparsity parameters and edge selection, critical for reproducible networks. |

Application in Disease Research

Network analysis has proven particularly valuable in differentiating diseased from healthy microbiomes. A meta-analysis of gut microbiomes across multiple diseases revealed that dysbiotic states are characterized by distinct network topologies [9]. Key findings include:

- Differentiation of Bacterial Phyla: The organization and connectivity of different bacterial phyla within the network change significantly in disease.

- Enrichment of Proteobacteria: Interactions involving Proteobacteria, a phylum often containing opportunistic pathogens, are frequently enriched in diseased networks [9].

- Identification of Microbial Guilds: Network analysis in liver-cirrhosis patients, for instance, successfully identified a "cirrhotic cluster"—a guild of bacteria associated with a degraded clinical host status [10]. Such guilds represent groups of microbes that co-occur and may interact synergistically, offering potential multi-taxa biomarkers for disease diagnosis and therapeutic targeting.

Why Network Analysis? Uncovering Guilds, Keystones, and Community Structure

Microbial communities are complex systems where the interactions between members are as critical as their individual identities. Network analysis provides a powerful framework to move beyond mere catalogues of "who is there" to understand the dynamic and interconnected nature of these communities. By representing microorganisms as nodes and their statistical associations as edges, this approach transforms complex microbiome data into interpretable maps of community structure. These maps are indispensable for identifying key ecological entities—keystone taxa that exert disproportionate influence on community stability and function, and guilds of organisms that work in concert to perform critical ecosystem processes. Within the context of microbiome network inference, this methodology reveals the hidden architecture of microbial communities, offering insights crucial for predicting ecosystem responses to perturbation and identifying high-value targets for therapeutic intervention.

Key Concepts: Guilds, Keystone Taxa, and Hubs

Keystone Taxa are functionally defined as taxa that have a profound effect on microbiome structure and functioning irrespective of their abundance [13]. Their removal—whether computational or experimental—is predicted to cause a drastic shift in the community composition and its metabolic output. The table below summarizes the core concepts central to network-level analysis.

Table 1: Key Ecological Concepts in Microbiome Network Analysis

| Concept | Definition | Ecological Role | Identification Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Keystone Taxa | Taxa that exert a considerable influence on the microbial community structure and function, disproportionate to their abundance [13]. | "Ecosystem engineers" that drive community composition and functional output; their loss can collapse the community structure. | High values of betweenness centrality in co-occurrence networks; Zi-Pi plot analysis; causal inference from time-series data [13] [14] [15]. |

| Microbial Hubs | Highly interconnected taxa within a network that form central connection points for multiple other taxa [16]. | Mediate the effects of host genotype and abiotic factors on the broader microbial community via microbe-microbe interactions [16]. | High values of degree (number of connections) and closeness centrality in co-occurrence networks. |

| Guilds | Groups of microbial taxa that utilize the same environmental resources in a similar way, often identified as tightly connected sub-networks. | Perform coordinated functions (e.g., hydrocarbon degradation, nitrogen cycling); provide functional redundancy and resilience. | Module or community detection algorithms within networks (e.g., Louvain method); clustering based on correlation patterns. |

The relationship between these concepts is often interactive. For instance, a keystone guild is a group of co-occurring keystone taxa that work together to drive a community function. One study demonstrated that Sulfurovum formed a mutualistic keystone guild with PAH-degraders like Novosphingobium and Robiginitalea, significantly enhancing the removal of the pollutant benzo[a]pyrene [14]. Furthermore, hub taxa can act as keystones; the pathogen Albugo and the yeast Dioszegia were identified as microbial "hubs" that strongly controlled the structure of the phyllosphere microbiome across kingdoms [16].

Experimental Protocols for Network Inference and Validation

A robust workflow for inferring and validating ecological networks from microbiome data involves sequential stages of data processing, network construction, statistical analysis, and experimental validation.

Protocol 3.1: Co-occurrence Network Construction and Analysis

This protocol outlines the process for building and analyzing a microbial co-occurrence network from 16S rRNA gene amplicon or metagenomic sequencing data, adapted from established methodologies [14] [15].

Key Research Reagents & Materials:

- High-Quality Sequencing Data: Raw FASTQ files from 16S rRNA gene amplicon or shotgun metagenomic sequencing of multiple samples.

- Bioinformatics Pipeline: Tools like QIIME 2, mothur, or HUMAnN for processing raw reads into a feature table (e.g., ASVs or species-level abundances).

- Computational Environment: R or Python with necessary libraries (e.g.,

vegan,igraph,FastSpar). - Correlation Algorithm: A tool designed for compositional data, such as FastSpar or SparCC [15].

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing: Process raw sequencing reads to obtain a count table of microbial features (OTUs, ASVs, or species) across all samples. Normalize the data (e.g., by converting to relative abundance) and apply a prevalence filter (e.g., retain features present in >10% of samples).

- Correlation Calculation: Calculate all pairwise correlations between microbial taxa using the FastSpar algorithm. Use recommended settings:

--iterations 100,--exclude_iterations 20,--threshold 0.1, and--number 1000for bootstrap analysis to assess significance [15]. - Network Construction: Create an undirected network where nodes represent microbial taxa. Establish an edge between two nodes if their correlation is statistically significant (p < 0.01 after multiple test correction) and meets a minimum correlation strength threshold (e.g., |r| > 0.6).

- Topological Analysis: Calculate network properties for each node using the

igraphpackage: - Identify Keystone Taxa: Rank taxa based on their betweenness centrality. Taxa in the top 5-10% are putative keystones. Validate this list using a Zi-Pi plot, which classifies nodes based on their within-module connectivity (Zi) and among-module connectivity (Pi). Module hubs have Zi > 2.5; Network hubs have Zi > 2.5 and Pi > 0.62 [13].

Protocol 3.2: The 3C-Strategy for Characterizing Keystone Taxa

This integrated strategy, combining co-occurrence network analysis, comparative genomics, and co-culture, provides a powerful framework for moving from correlation to causation in identifying keystone functions [14].

Procedure:

- Trigger and Track: Set up microcosm experiments with environmental samples, manipulating a key factor (e.g., adding a pollutant like BaP or a nutrient like nitrate). Track microbial community dynamics over time via sequencing to trigger role transitions in keystone taxa [14].

- Co-occurrence Network Analysis (First C): Construct and compare networks from the different treatments as described in Protocol 3.1. Identify taxa that transition to keystone roles (high betweenness) under specific conditions.

- Comparative Genomics (Second C): Perform metagenomic sequencing on selected samples. Reconstruct Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) of the identified putative keystone taxa. Annotate genes in these MAGs to infer their metabolic potential (e.g., stress resistance, nutrient cycling, degradation pathways) and understand the mechanistic basis for their keystone role [14].

- Co-culture (Third C): a. Capture: Isolate the putative keystone taxon and a key functional microbe (e.g., a primary degrader) from the same environment using cultivation-based methods. b. Label: Tag the functional microbe with a reporter gene like eGFP for visualization. c. Validate: Establish co-cultures of the keystone taxon and the functional microbe under stress conditions (e.g., pollutant toxicity). Measure and compare functional outputs (e.g., degradation efficiency, cell growth, stress marker removal) in co-culture versus mono-culture to experimentally verify the facilitating role of the keystone taxon [14].

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

Effective visualization is critical for interpreting the complex relationships and workflows in network analysis.

Diagram 1: A workflow integrating standard network analysis with the 3C-strategy for keystone taxon validation.

Diagram 2: Conceptual model of a keystone guild, illustrating the mutualistic interactions between a keystone taxon (Sulfurovum) and primary degraders that enhance ecosystem function.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Microbiome Network Analysis

| Item | Function / Application | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| FastSpar Software | Calculates robust correlations from compositional microbiome data for network construction. | Uses a linear Pearson correlation on log-transformed components; requires --iterations 100 and --number 1000 for bootstrap significance [15]. |

| Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) | Reconstructs genomes from complex metagenomic data to infer the metabolic potential of uncultured keystone taxa. | Generated from shotgun metagenomic sequencing using binning tools (e.g., MetaBAT2, MaxBin2). Critical for the "Comparative Genomics" step in the 3C-strategy [14]. |

| eGFP-labeling System | Tags and visualizes specific bacterial strains to track their growth and interactions in co-culture experiments. | Used in the "Co-culture" step to monitor the response of a key degrader in the presence of a putative keystone taxon under stress [14]. |

| hiTAIL-PCR | Captures flanking sequences of inserted genes, used to track and identify specific microbial degraders in a community. | A method to capture key degraders (e.g., for PAHs) that can then be labeled and used in co-culture validation [14]. |

| SparCC Algorithm | An alternative to FastSpar for inferring correlation networks from compositional data. | Estimates correlations after accounting for the compositional nature of relative abundance data [15]. |

| m-PEG12-azide | m-PEG12-azide|PEG Linker for Click Chemistry | |

| m-PEG5-sulfonic acid | m-PEG5-sulfonic acid, MF:C11H24O8S, MW:316.37 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Network analysis has emerged as a cornerstone of modern microbial ecology, providing the analytical framework to move from patterns to processes. By enabling the systematic identification of keystone taxa and functional guilds, it reveals the organizing principles of complex microbial communities. The integrated 3C-strategy—coupling Co-occurrence networks, Comparative genomics, and Co-culture—provides a robust, causally-oriented pipeline to validate the function of these key players. For researchers and drug development professionals, this methodology is transformative. It offers a rational approach to identify high-value targets for next-generation probiotics, design synthetic microbial consortia for bioremediation of pollutants like HMW-PAHs, and develop therapies that aim to steer dysbiotic communities back to a healthy state by manipulating their keystone elements. Understanding the network structure of a microbiome is the first step towards learning how to re-engineer it for human and environmental health.

Microbiome network inference is a powerful tool for unraveling the complex interactions among microorganisms in various ecological niches, from the human gut to environmental habitats [17]. These analyses model microbial communities as networks where nodes represent microbial taxa and edges represent significant associations between them, revealing the ecosystem's structure and stability [17] [3]. However, two intrinsic properties of microbiome sequencing data present substantial analytical challenges: compositionality and sparsity.

Compositional data arises because sequencing techniques measure relative abundances rather than absolute cell counts. The data is constrained to a constant sum (e.g., proportions summing to 1 or counts summing to the sequencing depth), meaning an increase in one taxon's abundance necessarily causes an apparent decrease in others [17] [3]. This property leads to spurious correlations if analyzed with standard statistical methods [17]. Simultaneously, microbiome data is highly sparse, containing an excess of zeros due to many low-abundance or rare taxa that are undetected in most samples [17]. This sparsity challenges the reliability of correlation estimates and network inference.

Table 1: Characteristics of microbiome datasets highlighting sparsity across different environments

| Dataset Name | Number of Taxa | Number of Samples | Sparsity (%) | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HMPv35 | 10,730 | 6,000 | 98.71 | Human body sites [18] |

| MovingPictures | 22,765 | 1,967 | 97.06 | Longitudinal human microbiome [18] |

| TwinsUK | 8,480 | 1,024 | 87.70 | Twin genetics study [18] |

| qa10394 | 9,719 | 1,418 | 94.28 | Sample preservation effects [18] |

| necromass | 36 | 69 | 39.78 | Soil decomposition [18] |

Table 2: Network inference methods addressing compositional and sparse data challenges

| Method | Approach | Handles Compositionality? | Handles Sparsity? | Longitudinal Data Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LUPINE | Partial correlation with low-dimensional approximation [3] | Yes | Yes | Yes (specialized) |

| MDSINE2 | Bayesian dynamical systems with interaction modules [19] | Indirectly via modeling | Yes | Yes (specialized) |

| SpiecEasi | Precision-based inference [3] | Yes | Yes | No |

| SparCC | Correlation-based with compositionality awareness [3] | Yes | Limited | No |

| fuser | Fused Lasso for multi-environment data [18] | Yes | Yes | Limited |

Computational Frameworks for Robust Inference

LUPINE: Longitudinal Modeling with Partial Least Squares Regression

The LUPINE (LongitUdinal modelling with Partial least squares regression for NEtwork inference) framework addresses compositionality through partial correlation while accounting for the influence of other taxa [3]. Its innovation lies in using one-dimensional approximation of control variables via principal component analysis (PCA) or projection to latent structures (PLS) regression, making it suitable for scenarios with small sample sizes and few time points [3].

LUPINE network inference workflow

MDSINE2: Dynamical Systems Modeling with Bayesian Inference

MDSINE2 (Microbial Dynamical Systems Inference Engine 2) employs a Bayesian approach to learn ecosystem-scale dynamical systems models from microbiome time-series data [19]. It addresses data challenges through several key innovations: explicit modeling of measurement uncertainty in sequencing data and total bacterial concentrations, incorporation of stochastic effects in dynamics, and automatic learning of interaction modules—groups of taxa with similar interaction structures [19].

The Fuser Algorithm for Cross-Environment Inference

The fuser algorithm applies fused Lasso to microbiome network inference, enabling information sharing across environments while preserving niche-specific associations [18]. This approach is particularly valuable for analyzing datasets with multiple environmental conditions or experimental groups, as it generates distinct predictive networks for different niches while leveraging shared information to improve inference accuracy [18].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: LUPINE_single for Cross-Sectional Data

Purpose: To infer robust microbial association networks from cross-sectional microbiome data while addressing compositionality and sparsity.

Materials:

- Microbial abundance data (OTU/ASV table)

- High-performance computing environment with R installed

- LUPINE_single software package

Procedure:

Data Preprocessing:

- Apply centered log-ratio (CLR) transformation or similar compositionality-aware normalization

- Filter rare taxa using prevalence and abundance thresholds (e.g., retain taxa present in >10% of samples)

- Optional: Impute zeros using Bayesian-multiplicative replacement or other sparse-data methods

Network Inference:

- For each taxon pair (i,j), extract the abundance vectors (X^i) and (X^j)

- Compute the first principal component of the control matrix (X^{-(i,j)}) containing all taxa except i and j

- Calculate the partial correlation between (X^i) and (X^j) conditional on the first principal component

- Repeat for all possible taxon pairs in the dataset

Significance Testing:

- Apply permutation-based significance testing (e.g., 1000 permutations)

- Adjust p-values for multiple testing using false discovery rate (FDR) control

- Retain only statistically significant associations after FDR correction (e.g., q-value < 0.05)

Network Construction:

- Create an adjacency matrix from significant partial correlations

- Apply a threshold to partial correlation coefficients to reduce false positives

- Construct the network graph with taxa as nodes and significant associations as edges [3]

Protocol: MDSINE2 for Longitudinal Data

Purpose: To infer microbial dynamics and interaction networks from longitudinal microbiome data with perturbations.

Materials:

- Longitudinal relative abundance data (16S rRNA or metagenomic sequencing)

- Total bacterial concentration measurements (from qPCR or flow cytometry)

- Sample metadata including perturbation timing

- MDSINE2 software package

Procedure:

Data Preparation:

- Align all samples by time and perturbation status

- Convert relative abundances to absolute abundances using total bacterial concentrations

- Perform quality control to remove poorly sampled time points

Model Training:

- Specify prior distributions for growth rates, interaction strengths, and perturbation responses

- Initialize interaction modules using phylogenetic information or clustering

- Run Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling to infer posterior distributions of parameters

Model Validation:

- Perform leave-one-subject-out cross-validation

- Assess forecast accuracy using root-mean-squared error (RMSE) of log abundances

- Compare against baseline methods (e.g., gLV-L2, gLV-net)

Network Analysis:

- Extract interaction networks from posterior means of interaction parameters

- Identify keystone taxa using betweenness centrality and interaction strength

- Evaluate community stability through eigenanalysis of the interaction matrix [19]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential computational tools and resources for microbiome network inference

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| LUPINE | R package | Longitudinal network inference | Handles small sample sizes, multiple time points [3] |

| MDSINE2 | Open-source software | Dynamical systems modeling | Bayesian inference of microbial interactions from time-series [19] |

| fuser | R/Python package | Multi-environment network inference | Preserves niche-specific signals while sharing information [18] |

| SAC Framework | Validation protocol | Same-All Cross-validation | Evaluates algorithm performance across environmental niches [18] |

| ColorBrewer 2.0 | Visualization tool | Color palette selection | Ensures accessible, colorblind-friendly network visualizations [20] |

| Chroma.js | Visualization tool | Color scale optimization | Creates perceptually balanced gradients for abundance visualizations [20] |

| MPX-007 | MPX-007, CAS:1688685-29-1, MF:C18H17F2N5O3S2, MW:453.4828 | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| NAB-14 | NAB-14, MF:C20H21N3O3, MW:351.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Advanced Visualization and Interpretation

Comprehensive workflow from raw data to interpretable networks

Effective visualization of microbial networks requires careful consideration of color and design. ColorBrewer 2.0 provides specialized color schemes for sequential, diverging, and qualitative data, ensuring that network nodes and edges are distinguishable while maintaining accessibility for colorblind readers [20]. For gradient-based visualizations of abundance data, the Chroma.js Color Scale Helper optimizes perceptual differences between steps, enabling accurate interpretation of microbial abundance patterns [20].

Network interpretation extends beyond visualization to topological analysis. Key metrics include degree centrality (number of connections per node), betweenness centrality (influence over information flow), and closeness centrality (efficiency of information spread) [17]. Additionally, identifying hub nodes (highly connected taxa), keystone species (disproportionate ecological impact), and network modules (strongly interconnected clusters) provides biological insights into community structure and stability [17].

Navigating compositional data and sparse datasets remains a core challenge in microbiome network inference, but methodological advances are steadily addressing these limitations. The integration of compositionality-aware statistical methods with Bayesian approaches that explicitly model uncertainty represents the current state-of-the-art. Emerging techniques like causal machine learning and Double ML show promise for moving beyond correlation to establish causal relationships in microbial communities [21]. As these methods mature and standardized validation frameworks like SAC gain adoption, microbiome network inference will become increasingly robust and reliable, ultimately enhancing its utility in therapeutic development and personalized medicine.

In microbiome research, network inference has become an indispensable tool for unraveling the complex dynamics of microbial communities. An edge in a microbial network represents a statistically inferred association between two microbial taxa or between a microbe and an environmental factor. This application note delineates the biological and ecological interpretations of network edges, providing a detailed protocol for their inference, validation, and contextualization within microbiome interaction studies. We further equip researchers with standardized workflows and analytical frameworks to enhance the rigor and biological relevance of network-based findings, ultimately supporting advancements in therapeutic development and microbiome engineering.

In microbial co-occurrence networks, nodes typically represent microbial taxa (e.g., species, genera, or OTUs/ASVs), while edges denote the statistical associations inferred between them based on their abundance patterns across multiple samples [22] [23]. These edges are not direct observations of interaction but are statistical inferences that suggest a potential biological or ecological relationship. The precise interpretation of an edge is contingent upon the experimental design, data preprocessing choices, and statistical inference methods employed [23] [24].

Understanding what an edge represents is critical because microbial interactions form the backbone of community dynamics and function. These interactions can influence host health, ecosystem stability, and therapeutic outcomes [22] [9]. Misinterpretation of edges can lead to flawed biological hypotheses; therefore, a rigorous approach to their inference and analysis is paramount.

Ecological Interpretation of Network Edges

Types of Ecological Interactions

The statistical associations captured by network edges can be mapped to several canonical forms of ecological relationships. These relationships are fundamentally defined by the net effect one microorganism has on the growth and survival of another [22].

Table 1: Ecological Interactions Represented by Network Edges

| Interaction Type | Effect of A on B | Effect of B on A | Potential Edge Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutualism | Positive (+) | Positive (+) | Positive co-occurrence edge; potential cross-feeding or synergism |

| Competition | Negative (–) | Negative (–) Negative co-occurrence edge; competition for resources or space | |

| Commensalism | Positive (+) | Neutral (0) | Directed or asymmetric edge; A benefits B without being affected |

| Amensalism | Negative (–) | Neutral (0) | Directed or asymmetric edge; A inhibits B without being affected |

| Parasitism/Predation | Positive (+) | Negative (–) | Directed edge; one organism benefits at the expense of the other |

This framework allows researchers to move beyond mere statistical associations and begin formulating testable biological hypotheses about the nature of microbial relationships [22] [25].

Signed, Weighted, and Directed Networks

The biological interpretability of a network is enhanced by defining the properties of its edges:

- Signed Networks: Edges are designated as positive or negative, distinguishing between putative mutualistic/commensal interactions and competitive/amensal ones [22].

- Weighted Networks: The strength of the association is quantified, allowing for the inference of interaction strength. A stronger correlation might indicate a more robust or influential biological relationship [22].

- Directed Networks: Edges have a direction (A → B), representing a hypothesized causal or influential relationship from one taxon to another. Inferring direction typically requires longitudinal (time-series) data, as cross-sectional data alone can typically only support undirected networks [22].

Quantitative Foundations of Edge Inference

Statistical Measures for Pairwise Association

The foundation of any co-occurrence network is the pairwise association measure. The choice of metric is critical and should be guided by the data's characteristics [26].

Table 2: Common Association Measures for Microbial Edge Inference

| Association Measure | Formula (Simplified) | Data Applicability | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson Correlation | ( r = \frac{\sum{i=1}^{n}(xi - \bar{x})(yi - \bar{y})}{\sqrt{\sum{i=1}^{n}(xi - \bar{x})^2}\sqrt{\sum{i=1}^{n}(y_i - \bar{y})^2}} ) | Normally distributed abundance data | Sensitive to outliers; assumes linearity. |

| Spearman's Rank Correlation | ( \rho = 1 - \frac{6 \sum d_i^2}{n(n^2 - 1)} ) | Non-normal data; ordinal abundance | Measures monotonic, not just linear, relationships. |

| SparCC | Based on log-ratio variances [26] | Compositional data (relative abundances) | Designed to mitigate compositionality artifacts. |

| Bray-Curtis Dissimilarity | ( BC{ij} = 1 - \frac{2C{ij}}{Si + Sj} ) | General abundance data; community ecology | Turns into similarity for network inference. |

Addressing Key Data Challenges

Microbiome data possess unique characteristics that, if unaddressed, can lead to spurious edges [23] [9].

- Compositionality: Data represent relative, not absolute, abundances, violating the independence assumption of many correlation metrics. This can be mitigated using compositionally aware methods like SparCC [26] or SPIEC-EASI [23] [9], or by applying transformations like the center-log ratio (CLR) [23].

- Sparsity and Zero-Inflation: Datasets contain many zeros due to true absence or undersampling. Prevalence filtering (e.g., retaining taxa present in >10-20% of samples) is commonly applied, though it risks excluding members of the rare biosphere [23].

- Sampling Heterogeneity: Varying sequencing depths between samples can introduce bias. Rarefaction is a common but debated normalization method; its effect depends on the downstream inference algorithm [23].

Detailed Protocol for Inferring and Validating Network Edges

Workflow for Microbial Network Inference

The following standardized protocol ensures robust and biologically interpretable network inference.

Protocol Steps

Stage 1: Data Preparation and Curation

Goal: Generate a clean, biologically relevant abundance table for network inference.

- Taxonomic Agglomeration: Cluster sequences into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) at 97% similarity or resolve into Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs). Decide on the taxonomic level (e.g., genus, species) for node identity [23].

- Data Filtering: Apply a prevalence filter to reduce zero-inflation and spurious correlations. A common threshold is retaining taxa present in at least 10-20% of samples. The specific threshold represents a trade-off between inclusivity and accuracy [23].

- Data Normalization:

- For correlation-based methods (e.g., Pearson, Spearman), consider rarefaction to even sequencing depth, though be aware of potential precision loss [23].

- For compositional-data methods, apply a center-log ratio (CLR) transformation to the entire dataset or use tools like

SPIEC-EASIorSparCCthat internally handle compositionality [23] [9].

- Inter-Kingdom Data: When integrating data from different domains (e.g., bacteria and fungi), transform and normalize each dataset independently before concatenation to avoid introducing bias [23].

Stage 2: Network Construction and Edge Selection

Goal: Infer a robust, sparse microbial association network.

- Software and Method Selection: Choose an inference method appropriate for your data and question.

- Correlation-based: CoNet, SparCC. Good for initial, undirected networks [24] [25].

- Conditional Dependence-based: SPIEC-EASI, gCoda, SPRING. Better for discerning direct from indirect interactions [24] [9].

- Ensemble Methods: OneNet. Combines multiple methods to produce a consensus network, often with higher precision [24].

- Edge Selection and Stability:

Stage 3: Biological Interpretation and Validation

Goal: Translate the statistical network into biologically meaningful insights.

- Topological Analysis: Calculate network properties (connectivity, modularity) and identify keystone taxa—highly connected hubs that may exert a disproportionate influence on the community regardless of their abundance [25].

- Hypothesis Generation: Map edge signs (positive/negative) to potential ecological interactions (Table 1). For example, a dense cluster of positive edges might indicate a microbial guild—a group of taxa performing a coordinated function [24] [9].

- Experimental Validation:

- Targeted Culturing: Co-culture taxa connected by strong edges to test for predicted interactions [23].

- Metabolomic Profiling: Correlate microbial abundance with metabolite data to identify potential mechanisms (e.g., the production of a specific growth-inhibiting compound) [27].

- Perturbation Experiments: Introduce a defined perturbation (e.g., antibiotics, nutrient shift) and track whether the predicted changes in connected taxa occur [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for Network Analysis

| Item Name | Function/Biological Role | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA Gene Primers (e.g., 338F/806R) | Amplify hypervariable regions for bacterial community profiling via amplicon sequencing [28]. | Generating taxonomic abundance data from environmental samples (e.g., gut, soil). |

| DNA Extraction Kit (e.g., QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit) | Isolate high-quality microbial genomic DNA from complex sample matrices [28]. | Standardized DNA extraction for sequencing from stool or luminal contents. |

| Greengenes Database | Curated 16S rRNA gene database for taxonomic classification of sequence variants [28]. | Assigning taxonomic identities to OTUs/ASVs after sequencing. |

| SPIEC-EASI Software | Statistical tool for inferring microbial ecological networks from compositional data [24] [9]. | Inferring conditional dependence networks that help distinguish direct from indirect interactions. |

| OneNet R Package | Consensus network inference method combining multiple algorithms for robust edge prediction [24]. | Generating a unified, more reliable network from microbiome abundance data. |

| NetCoMi R Package | Comprehensive toolbox for network construction, comparison, and analysis of microbiome data [24]. | Full pipeline analysis, from pre-processing to statistical comparison of networks. |

| Naldemedine | Naldemedine, CAS:916072-89-4, MF:C32H34N4O6, MW:570.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| N-Boc-PEG12-alcohol | N-Boc-PEG12-alcohol, MF:C29H59NO14, MW:645.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Considerations and Multi-Omics Integration

Moving beyond taxon-taxon associations, edges can represent relationships between different types of biological entities in a multi-omics network [27]. For instance, in a bipartite network, edges can connect:

- Microbial taxa to host metabolites, suggesting potential microbial modulation of the host metabolome [27].

- Microbial genes to expressed transcripts, linking genetic potential with activity [26].

- Fungal taxa to bacterial taxa, revealing cross-domain ecological interactions [23].

Inferring edges in multi-omics contexts requires sophisticated integration methods, such as Similarity Network Fusion or Multi-Omics Factor Analysis, which can handle the heterogeneous and high-dimensional nature of the data [27]. Crucially, the interpretation of an edge must now span different biological layers, requiring deep domain expertise.

An edge in a microbiome network is a gateway to formulating hypotheses about microbial interactions, not a definitive observation of a biological mechanism. Its accurate interpretation is deeply entangled with the choices made during data generation, preprocessing, and statistical inference. By adhering to standardized protocols, acknowledging the limitations of inference methods, and prioritizing experimental validation, researchers can robustly leverage network analysis to unravel the complex web of microbial interactions. This disciplined approach is fundamental for translating network inferences into meaningful biological discoveries and, ultimately, into novel therapeutic strategies for managing microbiome-associated diseases.

From Data to Networks: A Guide to Methodologies and Workflows

The field of microbiome research has rapidly evolved from cataloging microbial compositions to understanding the complex web of interactions that govern community dynamics and host health. Inferring these microbial interaction networks from high-throughput sequencing data presents unique statistical challenges due to the compositional, sparse, and high-dimensional nature of microbiome datasets [22]. Network inference algorithms serve as essential tools for reconstructing these complex ecological relationships, enabling researchers to identify key microbial players, understand community stability, and identify potential therapeutic targets [29] [22]. Within this context, inference algorithms can be broadly categorized into three methodological frameworks: correlation-based approaches, regression-based methods, and graphical models, each with distinct theoretical foundations, applications, and limitations for microbiome interaction analysis.

Correlation-Based Approaches

Correlation-based methods represent the most straightforward approach for inferring microbial associations by measuring pairwise statistical dependencies between taxa abundance profiles across samples. These methods identify co-occurrence (positive correlation) or mutual exclusion (negative correlation) patterns that may indicate ecological interactions such as competition, mutualism, or commensalism [22]. The fundamental concept of correlation as a statistical measure of association between two variables provides the foundation for these methods, with Pearson's correlation coefficient (r) quantifying the strength and direction of linear relationships [30].

Key Algorithms and Methodological Considerations

Table 1: Correlation-Based Network Inference Algorithms

| Algorithm | Correlation Type | Key Features | Applicable Data Types |

|---|---|---|---|

| SparCC [29] | Pearson | Accounts for compositionality; uses log-ratio transformations | Compositional count data |

| MENAP [29] | Pearson/Spearman | Employs Random Matrix Theory to determine significance thresholds | Relative abundance data |

| CoNet [29] | Multiple | Integrates multiple correlation measures with ensemble methods | General microbiome data |

| Traditional Pearson/Spearman [22] | Pearson/Spearman | Standard implementation; may produce spurious results in compositional data | Non-compositional data |

Correlation methods face particular challenges with microbiome data due to its compositional nature (data summing to a constant, typically 1 or 100%), which can lead to spurious correlations [3] [22]. Methods like SparCC address this limitation by using log-ratio transformations of the relative abundance data, providing more robust correlation estimates for compositional datasets [29].

Experimental Protocol: Implementing SparCC for Microbial Correlation Networks

Purpose: To infer microbial co-occurrence networks from compositional microbiome data using SparCC.

Materials:

- Input Data: OTU or ASV count table (samples × taxa)

- Software: Python with SparCC implementation (available through GitHub repositories)

- Computing Environment: Standard computational workstation with ≥8GB RAM

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing:

- Filter rare taxa with prevalence <10% across samples

- Apply additive log-ratio transformation to counts

- Optional: Address zeros using pseudocounts or multiplicative replacement

Parameter Configuration:

- Set number of iterations: 100 (default)

- Define variance threshold: 0.1 (typical for microbiome data)

- Specify number of bootstraps: 1000 for p-value calculation

Network Inference:

- Calculate correlations using iterative SparCC algorithm

- Generate p-values via bootstrap resampling

- Apply False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction (Benjamini-Hochberg, q<0.05)

Network Construction:

- Create adjacency matrix from significant correlations

- Define edges for |r| > 0.6 with q < 0.05

- Export network file for visualization (GML or GraphML format)

Interpretation: Positive correlations (r > 0) suggest potential cooperative relationships or shared environmental preferences, while negative correlations (r < 0) may indicate competitive exclusion or distinct niche preferences [22].

Regression-Based Methods

Regression-based approaches frame network inference as a variable selection problem, where the abundance of each taxon is predicted using the abundances of all other taxa in the community. These methods specifically aim to distinguish direct interactions from indirect associations by conditioning on other community members [29]. The core concept builds on simple linear regression principles, where a response variable (y) is modeled as a function of predictor variables (x), expressed as Å· = bâ‚€ + bâ‚x, with bâ‚€ representing the y-intercept and bâ‚ the slope coefficient [30].

Key Algorithms and Regularization Approaches

Table 2: Regression-Based Network Inference Algorithms

| Algorithm | Regression Framework | Regularization Approach | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCLasso [29] | Linear regression | LASSO (L1) | Uses log-ratio transformed data |

| REBACCA [29] | Linear regression | LASSO (L1) | Infers sparse microbial associations |

| SPIEC-EASI [29] | Linear regression | LASSO (L1) | Compositionally-aware framework |

| MAGMA [29] | Linear regression | LASSO (L1) | Infers sparse precision matrix |

| fuser [31] | Generalized linear model | Fused LASSO | Shares information across environments; preserves niche-specific signals |

| LUPINE [3] | PLS regression | Dimension reduction | Handles longitudinal data; uses PCA/PLS for low-dimensional approximation |

Regularization techniques, particularly LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator), are central to many regression-based approaches for microbiome network inference. LASSO applies an L1 penalty that shrinks regression coefficients toward zero, effectively performing variable selection and producing sparse networks where only the strongest associations are retained [29]. The recently introduced fuser algorithm extends this concept by applying fused LASSO to retain subsample-specific signals while sharing information across environments, generating distinct predictive networks for different ecological niches [31].

Experimental Protocol: SPIEC-EASI for Sparse Microbial Network Inference

Purpose: To infer sparse microbial interaction networks using the SPIEC-EASI framework.

Materials:

- Input Data: Filtered OTU/ASV count table

- Software: R with SPIEC.EASI package

- Computing Environment: RStudio with ≥8GB RAM

Procedure:

- Data Preparation:

- Center-log ratio (CLR) transform count data

- Optional: Address zeros using Bayesian-multiplicative replacement

Model Selection:

- Choose neighborhood selection (MB) or graphical lasso (Glasso) approach

- Set stability selection threshold: 0.05 (recommended for microbiome data)

- Define number of lambda (penalty) parameters to test: 50

Model Fitting:

- Execute SPIEC-EASI with selected parameters

- Perform model selection via StARS (Stability Approach to Regularization Selection)

- Retain edges with stability >0.9

Network Refinement:

- Apply model checking for goodness-of-fit

- Calculate edge weights from precision matrix

- Export network file with edge weights and confidence scores

Interpretation: The resulting network represents conditional dependencies between taxa, where edges indicate direct associations after accounting for all other taxa in the community. The edge weights correspond to partial correlations derived from the precision matrix [29].

Graphical Models

Graphical models represent the most sophisticated approach to network inference, combining graph theory with probability theory to model complex dependency structures among microbial taxa [32]. These models represent variables as nodes in a graph and conditional dependencies as edges, providing a framework for representing both the structure and strength of microbial interactions [33] [34]. In Gaussian Graphical Models (GGMs), a specific type of graphical model, partial correlations are derived from the inverse of the covariance matrix (precision matrix), where a zero entry indicates conditional independence between two variables after accounting for all other variables in the model [35].

Key Algorithms and Mathematical Formulation

Table 3: Graphical Model-Based Network Inference Algorithms

| Algorithm | Model Type | Key Features | Data Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| gCoda [29] | GGM | Compositionally-aware GGM | Cross-sectional microbiome data |

| mLDM [29] | Latent Dirichlet Model | Bayesian approach with latent variables | Multinomial count data |

| MDiNE [29] | Bayesian GGM | Models microbial interactions in case-control studies | Case-control microbiome data |

| COZINE [29] | GGM | Compositional zero-inflated network estimation | Sparse microbiome data |

| HARMONIES [29] | GGM | Uses centered log-ratio transformation with priors | Compositional data |

| Cluster-based Bootstrap GGM [35] | GGM | Handles correlated data (e.g., longitudinal, family studies) | Clustered or longitudinal data |

For a random vector Y = (Yâ‚, Yâ‚‚, ..., Yâ‚š) following a multivariate normal distribution, the partial correlation between Yáµ¢ and Yâ±¼ given all other variables is defined as Ïᵢⱼ = -kᵢⱼ/√(kᵢᵢkⱼⱼ), where kᵢⱼ represents the (i,j)th entry of the precision matrix K = Σâ»Â¹ [35]. An edge exists between two variables in the graph if the partial correlation between them is significantly different from zero, indicating conditional dependence.

Experimental Protocol: Gaussian Graphical Models for Microbial Conditional Dependence Networks

Purpose: To infer microbial interaction networks using Gaussian Graphical Models that represent conditional dependence relationships.

Materials:

- Input Data: CLR-transformed abundance data

- Software: R with huge or mgm packages

- Computing Environment: Computational server with ≥16GB RAM for large datasets

Procedure:

- Data Transformation:

- Apply CLR transformation to count data

- Check multivariate normality assumptions

- Standardize variables to mean=0, variance=1

Precision Matrix Estimation:

- Select estimation method (graphical lasso, neighborhood selection)

- Set penalty parameter via cross-validation or information criteria

- Compute precision matrix with selected regularization

Significance Testing:

- Calculate partial correlations from precision matrix

- Perform Fisher's z-transformation: z = 0.5 × log((1+r)/(1-r))

- Test null hypothesis Hâ‚€: Ïᵢⱼ = 0 using reference distribution N(0, 1/(n-p-3))

Network Construction:

- Retain edges with FDR-corrected p-value < 0.05

- Apply optional stability selection

- Validate network structure with bootstrap resampling (100 iterations)

Interpretation: In the resulting GGM, edges represent direct conditional dependencies between taxa after accounting for all other taxa in the model. The absence of an edge between two taxa indicates conditional independence, suggesting no direct ecological interaction [35] [34].

Comparative Analysis and Applications

Performance Considerations Across Data Types

The selection of an appropriate inference algorithm depends critically on study design, data characteristics, and research objectives. Correlation-based methods generally offer computational efficiency but may capture both direct and indirect associations, potentially leading to spurious edges [22]. Regression-based approaches, particularly those with regularization, better distinguish direct interactions but require careful parameter tuning [29] [31]. Graphical models provide the most rigorous framework for conditional dependence but have stronger distributional assumptions and computational demands [35] [34].

For longitudinal microbiome studies, specialized methods like LUPINE (LongitUdinal modelling with Partial least squares regression for NEtwork inference) leverage information from multiple time points to capture dynamic microbial interactions [3]. When analyzing data with inherent correlations, such as family-based studies or repeated measurements, the cluster-based bootstrap GGM approach controls Type I error inflation without sacrificing statistical power [35].

Validation Frameworks

Robust validation of inferred networks remains challenging in microbiome research due to the lack of ground truth networks. Cross-validation approaches, such as the Same-All Cross-validation (SAC) framework, provide a method for evaluating algorithm performance by testing predictive accuracy both within and across environmental niches [31]. External validation using experimental data or comparison with established microbial relationships further strengthens confidence in inferred networks [22].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Microbiome Network Inference

| Resource Type | Specific Tools/Platforms | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Data Processing | QIIME 2, DADA2, mothur | Processes raw sequencing data into OTU/ASV tables |

| Statistical Software | R, Python, MATLAB | Provides environment for statistical analysis and network inference |

| Specialized R Packages | SPIEC.EASI, huge, mgm, phyloseq | Implements specific network inference algorithms |

| Specialized Python Libraries | Scikit-learn, NumPy, SciPy | Provides general machine learning and statistical functions |

| Visualization Tools | Cytoscape, Gephi, R/ggraph | Enables network visualization and exploration |

| Validation Frameworks | SAC (Same-All Cross-validation) [31] | Evaluates algorithm performance across environments |

Workflow and Conceptual Diagrams

Microbiome Network Inference Workflow

Algorithm Taxonomy and Characteristics

Microbial communities are complex ecosystems where interactions between microorganisms play a crucial role in determining community structure and function across diverse environments, from the human gut to soil and aquatic systems [36] [37]. Understanding these complex interactions is essential for advancing knowledge in fields ranging from human health to ecosystem ecology. The emergence of high-throughput sequencing technologies has enabled researchers to profile microbial communities, generating vast amounts of taxonomic composition data [38] [39]. However, analyzing these data presents significant statistical challenges due to their unique characteristics, including compositional constraints, high dimensionality, and zero-inflation [37] [40].

Network inference approaches provide a powerful framework for identifying potential ecological relationships between microbial taxa from compositional data [41]. In these microbial co-occurrence networks, nodes represent taxonomic units, and edges represent significant associations—either positive (co-occurrence) or negative (mutual exclusion) [39]. However, standard correlation metrics applied directly to raw compositional data can produce spurious associations due to the inherent data constraints, necessitating specialized compositionally-robust methods [37] [42]. This application note focuses on three pivotal methods—SPIEC-EASI, SparCC, and CCLasso—that address these challenges through different statistical frameworks for accurate microbial network inference.

Methodological Foundations

The Compositionality Problem in Microbiome Data