Microbiome Pipeline Reproducibility: A Comprehensive Comparison of DADA2, QIIME2, and MOTHUR for Robust Biomedical Research

Reproducibility in microbiome bioinformatics is paramount for translating microbial signatures into clinical and pharmaceutical applications.

Microbiome Pipeline Reproducibility: A Comprehensive Comparison of DADA2, QIIME2, and MOTHUR for Robust Biomedical Research

Abstract

Reproducibility in microbiome bioinformatics is paramount for translating microbial signatures into clinical and pharmaceutical applications. This article provides a systematic evaluation of three widely used bioinformatics pipelines—DADA2, QIIME2, and MOTHUR—assessing their consistency in revealing microbial community structures. Drawing on recent comparative studies, we explore the foundational principles of Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) and Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs), detail best-practice methodologies, and offer troubleshooting guidance for common analytical pitfalls. A core focus is the validation of pipeline outputs, demonstrating that while relative abundance estimates may vary, robust biological conclusions on key features like Helicobacter pylori status and microbial diversity are reproducible across platforms. This resource is tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to implement reliable, reproducible, and clinically translatable microbiome analyses.

The Reproducibility Challenge: Foundational Concepts in Microbiome Bioinformatics

In microbiome research, the transition from raw genetic data to biological insight relies on complex bioinformatic pipelines. The choice of these analytical tools is not merely a technical detail but a fundamental decision that shapes research outcomes. As the field moves toward clinical and translational applications, the reproducibility of results across different computational methods has emerged as a critical concern. This guide objectively compares three widely used pipelines—DADA2, MOTHUR, and QIIME 2—by examining experimental data that benchmark their performance, providing researchers with evidence-based insights for selecting appropriate analytical frameworks.

The Reproducibility Challenge in Microbiome Analysis

Microbiome analysis presents unique reproducibility challenges due to the multi-step processing of sequencing data. Different bioinformatic approaches can introduce variability in the final microbial community profiles, potentially impacting biological interpretations. A 2025 comparative study investigating gastric mucosal microbiome composition found that although H. pylori status, microbial diversity, and relative bacterial abundance were reproducible across DADA2, MOTHUR, and QIIME 2, differences in performance were still detectable [1]. This paradox—core findings remaining stable while nuanced differences emerge—underscores the complexity of pipeline comparisons. Similarly, a 2020 evaluation of gut microbiota analyses reported that taxa assignments were consistent at both phylum and genus level across pipelines, but significant differences emerged in relative abundance estimates for most abundant genera [2]. These findings highlight that pipeline choice can simultaneously preserve broad taxonomic patterns while altering specific abundance measurements, creating a nuanced reproducibility landscape where the level of biological inference matters greatly.

Pipeline Comparison: Performance and Experimental Data

- DADA2: A package that infers amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) using a parametric error model to correct sequencing errors, providing single-nucleotide resolution [3] [4].

- MOTHUR: A comprehensive pipeline that facilitates processing sequencing data primarily through operational taxonomic unit (OTU) clustering, following a 97% similarity threshold traditionally [4].

- QIIME 2: A modular platform that can incorporate multiple analysis methods, including DADA2 for denoising, and offers extensive visualization tools and provenance tracking [5].

Comparative Performance Metrics

Table 1: Pipeline Performance Based on Mock Community Validation Studies

| Pipeline | Clustering Approach | Species-Level Accuracy | Genus-Level Accuracy | Computational Efficiency | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DADA2 | ASV (100% identity) | Variable across studies | High (>90%) | Moderate | Superior single-nucleotide resolution; minimal inflation of diversity [4] |

| MOTHUR | OTU (97% identity) | Moderate | High | Lower for large datasets | Extensive data preprocessing options; well-established protocols [4] |

| QIIME 2 | Flexible (ASV or OTU) | Dependent on plugins | High | Varies with plugins | User-friendly interfaces; provenance tracking; reproducible workflows [5] |

| Kraken 2 | Alignment-free k-mer | High in recent evaluations | High | Fast | Excellent species-level identification; handles large datasets efficiently [4] |

| PathoScope 2 | Bayesian reassignment | High in recent evaluations | High | Computationally intensive | Superior species-level performance; reduces false positives [4] |

Table 2: Impact of Reference Database on Taxonomic Classification Accuracy

| Reference Database | Last Update | Taxonomic Breadth | Recommended Use Cases | Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SILVA | 2020 (v138.1) | Comprehensive bacteria, archaea, eukaryotes | General purpose; high taxonomic resolution | All major pipelines [1] [4] |

| Greengenes | 2013 (13_8) | Bacterial and archaeal focus | Legacy comparisons; backward compatibility | QIIME 2 (default) [4] |

| RefSeq | Continuously updated | Whole genome focus | Species-level resolution; metagenomic applications | PathoScope, Kraken 2 [4] |

| RDP | Regularly maintained | Bacterial and fungal focus | Fungal analyses; ribosomal gene studies | Mothur, DADA2 [6] |

Recent benchmarking studies using mock communities with known compositions provide critical insights into pipeline performance. A 2023 comprehensive evaluation of 136 mock community samples revealed that tools designed for whole-genome metagenomics, specifically PathoScope 2 and Kraken 2, outperformed specialized 16S analysis tools (DADA2, QIIME 2, and MOTHUR) in species-level taxonomic assignment [4]. This finding challenges conventional wisdom that specialized 16S pipelines inherently provide superior performance for amplicon data. The study further identified that reference database selection significantly impacts accuracy, with SILVA and RefSeq/Kraken 2 Standard libraries outperforming the outdated Greengenes database [4].

Standardized Experimental Protocols for Pipeline Validation

Multi-Laboratory Reproducibility Assessment

A 2025 international ring trial established a robust protocol for evaluating pipeline reproducibility across five independent laboratories [7]. The experimental design incorporated:

- Standardized Ecosystems: Used fabricated ecosystem devices (EcoFAB 2.0) with the model grass Brachypodium distachyon and synthetic microbial communities (SynComs) to control biotic and abiotic factors [7].

- Controlled Variables: All laboratories received identical materials, including EcoFABs, seeds, synthetic community inoculum, and filters from a central source [7].

- Detailed Protocols: Provided comprehensive written protocols and annotated videos to minimize technical variation across sites [7].

- Centralized Analysis: Conducted all sequencing and metabolomic analyses in a single laboratory to reduce analytical variability [7].

This multi-laboratory approach demonstrated that consistent plant traits, exudate profiles, and microbiome assembly could be achieved across different research settings when standardized protocols were implemented [7].

Mock Community Benchmarking Methodology

The most rigorous approach for pipeline validation utilizes mock microbial communities with known compositions:

- Community Design: Create defined mixtures of microbial strains with staggered abundances and varying richness (e.g., 8-21 species) [4].

- Sequencing Variation: Amplify different variable regions (V3-V5) of the 16S rRNA gene using multiple primer sets and sequence across platforms (Illumina MiSeq, Ion Torrent) [4].

- Data Processing: Apply identical quality filtering to raw sequences before analysis with different bioinformatics pipelines [4].

- Accuracy Assessment: Compare pipeline outputs to expected compositions using sensitivity, specificity, and diversity measures [4].

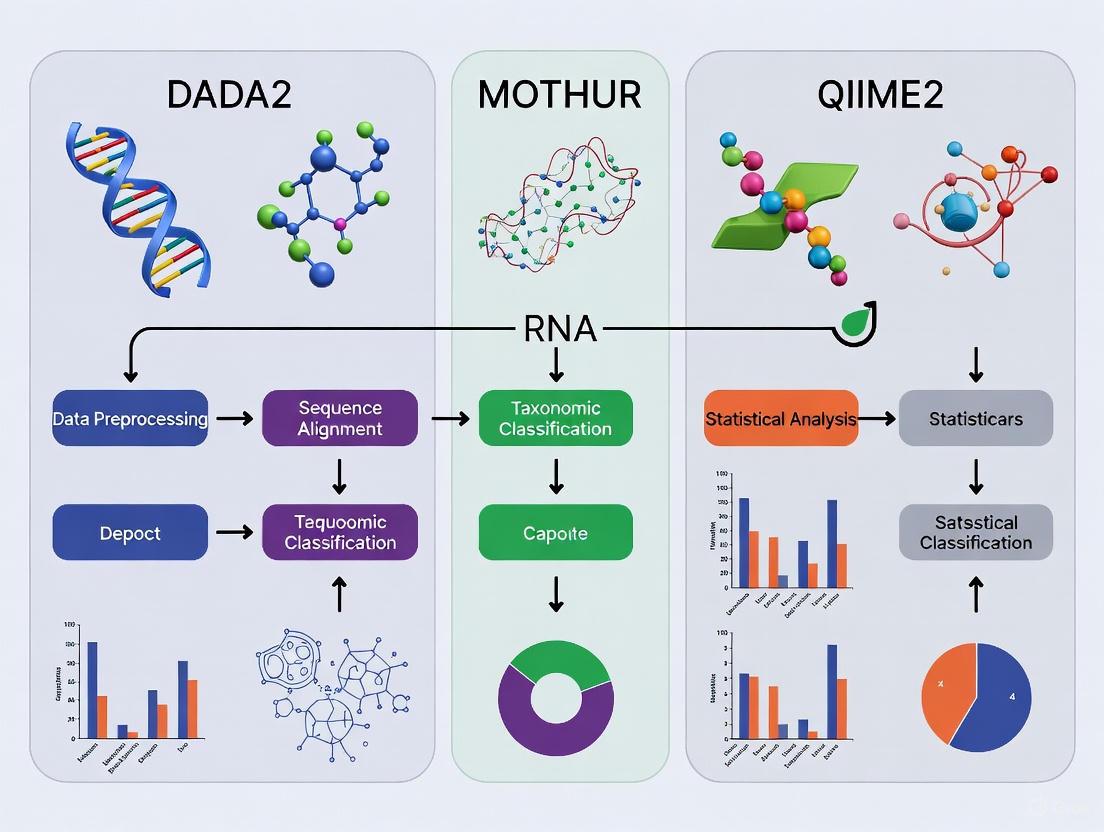

Visualization of Microbiome Analysis Workflows

Diagram 1: Comparative workflow architectures of DADA2, QIIME 2, and MOTHUR pipelines highlight fundamental differences in sequence processing approaches, from initial quality control to final taxonomic classification.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Resources for Reproducible Microbiome Analysis

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in Analysis | Considerations for Reproducibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Databases | SILVA, Greengenes, RefSeq | Taxonomic classification backbone | Database version control critical; prefer regularly updated databases [1] [4] |

| Mock Communities | BEI Mock Communities B & C, custom synthetic communities | Pipeline validation and benchmarking | Essential for establishing accuracy baselines [4] |

| Quality Control Tools | FastQC, MultiQC | Assess raw sequence quality | Identifies technical artifacts before analysis [6] |

| Analysis Pipelines | DADA2, QIIME 2, MOTHUR, LotuS2 | Core data processing | Version control essential; consider computational requirements [8] [4] |

| Visualization Packages | phyloseq, ggplot2, PCoA/NMDS plots | Data interpretation and exploration | Standardized visualization enables cross-study comparisons [6] |

| Workflow Management | Snakemake, Conda, Docker | Computational reproducibility | Environment encapsulation prevents dependency conflicts [9] |

Strategies for Enhancing Reproducibility

Achieving reproducible microbiome research requires both technical and methodological rigor. The following strategies emerge from recent comparative studies:

Implement Provenance Tracking: QIIME 2's integrated provenance system automatically tracks all analysis steps, creating an auditable trail from raw data to final results [5].

Standardize Experimental Protocols: As demonstrated in multi-laboratory studies, distributing identical materials and detailed protocols significantly reduces inter-laboratory variability [7].

Utilize Mock Communities: Regular validation with mock communities of known composition provides quality control and performance benchmarking [4].

Select Updated Reference Databases: Database currency significantly impacts accuracy, with SILVA and RefSeq outperforming outdated alternatives [4].

Adopt Transparent Reporting: Documenting software versions, parameters, and database references enables proper evaluation and replication [1].

Consider Hybrid Approaches: Emerging evidence suggests that metagenomic-focused tools like Kraken 2 and PathoScope may offer advantages for species-level identification in 16S data [4].

The choice of bioinformatics pipeline fundamentally shapes microbiome research outcomes and reproducibility. While DADA2, MOTHUR, and QIIME 2 can generate broadly consistent results for major biological patterns, significant differences emerge in species-level resolution, abundance estimates, and overall data structure. Evidence from standardized comparisons indicates that methodological choices, including reference database selection and computational approaches, can produce variability that impacts biological interpretation. As the field progresses, researchers must prioritize transparent reporting, standardized validation, and thoughtful pipeline selection based on specific research questions rather than convention alone. By adopting rigorous reproducibility practices and leveraging experimental data from pipeline comparisons, the microbiome research community can enhance the reliability and translational potential of their findings.

In targeted 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing, bioinformatic pipelines transform raw sequencing reads into meaningful biological units that represent the taxonomic composition of a sample. The field has undergone a significant methodological evolution, primarily divided into two approaches: the established Operational Taxonomic Unit (OTU) clustering method and the more recent Amplicon Sequence Variant (ASV) method. OTUs are clusters of sequencing reads grouped based on a predefined sequence similarity threshold, traditionally 97%, which approximates species-level differentiation [10] [11]. This approach intentionally blurs similar sequences into a consensus to minimize the impact of sequencing errors [10]. In contrast, the ASV approach employs denoising algorithms to identify exact biological sequences, distinguishing true variants from sequencing errors down to a single-nucleotide resolution without arbitrary clustering [10] [12] [11]. This fundamental difference in philosophy—clustering versus error-correcting—has profound implications for resolution, reproducibility, and the types of biological inferences that can be drawn from microbial community data.

Key Conceptual Differences Between OTUs and ASVs

The distinction between OTUs and ASVs is not merely technical but conceptual, influencing how microbial diversity is quantified and interpreted. The following table summarizes the core differences:

Table 1: Fundamental differences between the OTU and ASV approaches.

| Feature | OTU (Operational Taxonomic Unit) | ASV (Amplicon Sequence Variant) |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Principle | Clusters sequences based on a similarity threshold (e.g., 97%) [10] [12] | Identifies exact, error-corrected sequences; single-nucleotide resolution [12] [11] |

| Error Handling | "Averages out" errors by clustering them with true sequences [10] | Uses an error model to positively identify and remove sequencing errors [10] [12] |

| Resolution | Lower resolution; groups closely related strains and species [10] | High resolution; can distinguish between closely related strains [10] [11] |

| Reproducibility | Study-dependent; clusters can change with added data or different parameters [10] | Highly reproducible; exact sequences are stable across studies [10] [11] |

| Computational Demand | Generally less computationally intensive [11] | More computationally demanding due to denoising algorithms [11] |

| Biological Assumption | Assumes a meaningful level of diversity occurs above a fixed similarity cutoff | Assumes that true biological sequences can be discerned from noise, regardless of abundance |

Benchmarking Performance: Experimental Data from Comparative Studies

Numerous independent studies have benchmarked the performance of OTU and ASV-based pipelines using mock microbial communities (with known compositions) and large real-world datasets. The consensus indicates that ASV-based pipelines generally offer superior sensitivity and specificity, though performance varies among specific tools.

Performance on Mock Communities

A 2020 study by Prodan et al. compared six pipelines using a mock community of 20 bacterial strains, which contained 22 true sequence variants in the V4 region [13] [14]. The study's key findings on sensitivity and specificity are summarized below:

Table 2: Performance of different bioinformatic pipelines on a mock community as evaluated by Prodan et al. (2020). F-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall.

| Pipeline | Type | Sensitivity | Specificity | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DADA2 | ASV | Best | Lower than UNOISE3/Deblur | Highest sensitivity, but at the expense of specificity [13] [14] |

| USEARCH-UNOISE3 | ASV | High | Best | Best balance between resolution and specificity [13] [14] |

| Qiime2-Deblur | ASV | High | High | Strong performance, high specificity [13] [14] |

| USEARCH-UPARSE | OTU | Good | Good (but lower than ASV) | Performed well, but with lower specificity than ASV-level pipelines [13] [14] |

| MOTHUR | OTU | Good | Good (but lower than ASV) | Performed well, but with lower specificity than ASV-level pipelines [13] [14] |

| QIIME-uclust | OTU | - | - | Produced a large number of spurious OTUs; not recommended [13] [14] |

Another benchmarking study that included the LotuS2 pipeline reported that it achieved high accuracy, with 83% of reads correctly assigned at the genus level and 48% at the species level in a mock community, with the highest F-score at the ASV/OTU level compared to other pipelines [8].

Impact on Diversity Metrics and Ecological Interpretation

The choice of pipeline can significantly impact downstream ecological analysis. A 2022 study by Chiarello et al. found that the choice between DADA2 (ASV) and MOTHUR (OTU) had a stronger effect on alpha and beta diversity measures than other common methodological choices like rarefaction or OTU identity threshold (97% vs. 99%) [12] [15]. The effect was most pronounced on presence/absence indices like richness and unweighted UniFrac [12] [15]. Furthermore, different pipelines can alter the perceived relative abundance of key taxa. For instance, a comparison of four pipelines on human fecal samples found significant differences in the estimated relative abundance of major genera like Bacteroides [2] [16].

Detailed Experimental Protocols from Cited Studies

To ensure reproducibility and provide context for the performance data, here are the detailed methodologies from two key benchmarking studies.

Protocol: Prodan et al. (2020) Comparison

This study compared six pipelines using a mock community and a large human fecal dataset (N=2170) from the HELIUS study [13] [14].

- Sample Types:

- Mock Community: Genomic DNA from Microbial Mock Community B (HM-782D, BEI Resources), containing 20 bacterial strains with a known composition of 22 true sequence variants in the V4 region [13] [14].

- Human Fecal Samples: 2170 samples from the multi-ethnic HELIUS study, sequenced across 17 runs [13] [14].

- Wet-Lab Protocol:

- Bioinformatic Pipelines & Key Parameters:

- OTU-based: QIIME-uclust (v1.9.1), MOTHUR (v1.39.5), USEARCH-UPARSE (v10.0.240). Clustering was performed at 97% identity.

- ASV-based: DADA2 (v1.7.0), Qiime2-Deblur (v2017.6.0), USEARCH-UNOISE3 (v10.0.240).

- Read Processing: For pipelines other than DADA2 and MOTHUR, merged reads were processed with USEARCH using specific parameters: maxdiffs=30 in the merging step and max expected errors (maxee)=1 for quality filtering to maximize read retention and error correction [13] [14].

Protocol: Chiarello et al. (2022) Comparison

This study focused on the comparative effect of pipeline choice versus other common methodological decisions in environmental and host-associated samples [12] [15].

- Sample Types:

- Wet-Lab Protocol:

- Bioinformatic Pipelines & Key Parameters:

- OTU-based: MOTHUR (v1.8.0) following the MiSeq SOP. Sequences were aligned to the SILVA v138 database, and chimeras were removed with VSEARCH. OTUs were generated at 97% and 99% identity thresholds [12] [15].

- ASV-based: DADA2 (R package, v1.16) with standard denoising parameters [12] [15].

- Downstream Analysis: The community tables were used to compare the effects of pipeline choice, rarefaction level, and OTU threshold on alpha and beta diversity metrics [12] [15].

Logical Workflow of OTU vs. ASV Pipelines

The following diagram illustrates the core logical differences in how OTU-based and ASV-based pipelines process raw sequencing reads to arrive at their final output.

For researchers aiming to conduct similar comparative analyses or standardize their microbiome workflow, the following tools and databases are essential.

Table 3: Essential reagents, software, and databases for microbiome bioinformatics.

| Item Name | Type | Function / Application | Example Source / Version |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mock Microbial Community | Standard | Validates pipeline accuracy and sensitivity using a sample of known composition. | BEI Resources, HM-782D [13] [14] |

| Silva SSU rRNA Database | Reference Database | Provides a curated taxonomy and alignment reference for 16S rRNA gene sequences. | SILVA 132/138 [2] [12] [16] |

| DADA2 | R Package / ASV Pipeline | Infers amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) from Illumina amplicon data via a parametric error model and denoising. | R package, v1.7.0+ [13] [12] [14] |

| QIIME 2 (with Deblur) | Framework / ASV Pipeline | An open-source, scalable microbiome analysis platform with Deblur for ASV inference via error profile-based subtraction. | Qiime2 v2017.6.0+ [13] [14] |

| USEARCH (UNOISE3/UPARSE) | Software Suite | A versatile tool suite offering both ASV (UNOISE3) and OTU (UPARSE) clustering algorithms. | USEARCH v10.0.240+ [13] [14] |

| MOTHUR | Software Suite / OTU Pipeline | A comprehensive, single-purpose software for the OTU-based analysis of 16S rRNA sequence data. | MOTHUR v1.39.5+ [13] [12] [14] |

| LotuS2 | Software Pipeline | A lightweight, user-friendly pipeline offering multiple clustering algorithms (DADA2, UNOISE3, VSEARCH) and high speed [8]. | LotuS2 [8] |

The collective evidence from rigorous benchmarking studies indicates a paradigm shift in microbiome bioinformatics from OTU-based clustering toward ASV-based denoising. ASV methods (DADA2, QIIME2-Deblur, UNOISE3) provide superior resolution, higher reproducibility across studies, and more effective correction of sequencing errors [10] [13] [11]. While OTU-based pipelines like MOTHUR and UPARSE remain valid and can perform well, particularly in well-characterized environments like the human gut, they generally exhibit lower specificity and are more susceptible to reference database biases [10] [13].

The choice of the specific ASV pipeline, however, involves trade-offs. DADA2 often demonstrates the highest sensitivity for detecting true variants, sometimes at the cost of specificity, while UNOISE3 frequently strikes the best balance between resolution and specificity [13] [14]. For research questions requiring the detection of fine-scale ecological patterns or precise tracking of strains across studies, ASVs are the unequivocal choice. The field's movement towards ASVs, supported by robust experimental data, underscores the importance of higher accuracy and cross-study comparability in advancing microbiome science.

The Impact of Analytical Variability on Biological Interpretation and Clinical Translation

Microbiome research has become a cornerstone of basic and translational science, with significant potential for informing clinical practice [1]. However, the translational path from microbial insights to clinical applications remains challenging, constrained by methodological and analytical limitations [17]. A critical source of this constraint is analytical variability—the variation introduced by different bioinformatic processing methods, which can significantly impact biological interpretation and hinder clinical translation. This guide provides an objective comparison of three widely used bioinformatics pipelines—DADA2, MOTHUR, and QIIME2—focusing on their performance in reproducing microbial community analyses, a fundamental prerequisite for reliable biological interpretation and downstream clinical application.

Performance Comparison of Major Bioinformatics Pipelines

Comparative studies reveal that while different bioinformatics pipelines can generate broadly consistent results, significant differences in performance metrics exist that can influence biological interpretation.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Bioinformatics Pipelines across Study Types

| Pipeline | Primary Output | Sensitivity & Specificity Balance | Reproducibility of Microbial Patterns | Key Findings from Comparative Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DADA2 | Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) | High sensitivity, but may have lower specificity compared to UNOISE3 [14]. | Reproducible results for H. pylori status, diversity, and relative abundance [1]. | Resolves sequences to single-nucleotide differences; provides the finest resolution [2]. |

| MOTHUR | Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) | Good performance, though may show lower specificity compared to ASV-level pipelines [14]. | Reproducible outcomes in microbial composition across independent research groups [1]. | Uses a clustering-based approach (typically 97% identity); a well-established, standardized tool [2]. |

| QIIME2 | ASVs (via plugins like DADA2, Deblur) or OTUs | Varies with plugin. Overall, generates comparable results to other robust pipelines [1]. | Consistent identification of inoculum-dependent changes in plant phenotype and microbiome [7]. | A modular, extensible framework that supports multiple modern denoising algorithms [2]. |

Table 2: Impact of Pipeline Choice on Downstream Analytical Results

| Analysis Type | Impact of Pipeline Variability | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Taxonomic Assignment | Relative abundance estimates for phyla and genera can differ significantly (p < 0.05) even when taxa identities are consistent [2]. | A study on human stool samples found significant differences in abundant genera like Bacteroides across pipelines [2]. |

| Alpha-Diversity | Inflated or altered diversity measures can occur with some pipelines, potentially masking or exaggerating biological effects [14]. | QIIME-uclust (an older pipeline) was noted to produce inflated alpha-diversity and should be avoided [14]. |

| Community Structure | Core biological findings (e.g., disease-associated shifts) are generally reproducible across robust pipelines, enabling reliable high-level interpretation [1]. | Five independent research groups using different protocols reproducibly identified H. pylori-driven microbial changes in gastric cancer [1]. |

Experimental Protocols for Pipeline Comparison

To ensure rigorous and reproducible comparisons, studies must employ standardized experimental designs and protocols. The following methodologies are derived from published comparative analyses.

Sample Collection and DNA Sequencing

- Sample Types: Studies utilize both mock communities (artificial mixtures of known microbial strains) and real biological samples (e.g., human stool, gastric biopsies, plant rhizospheres) [14] [1] [7]. Mock communities provide a ground truth for evaluating sensitivity and specificity, while real samples assess performance under realistic conditions.

- Laboratory Protocols: For human gut microbiome studies, DNA is typically extracted from stool samples (e.g., 150-200 mg) using kits with bead-beating mechanical disruption. The 16S rRNA gene (e.g., V3-V4 or V4 hypervariable regions) is amplified with primers containing Illumina adapter sequences. Libraries are then normalized, pooled, and sequenced on Illumina platforms (e.g., MiSeq) [2] [14].

- Multi-Laboratory Design: To assess reproducibility, a ring trial design can be implemented where multiple laboratories receive identical materials (e.g., synthetic communities, seeds, EcoFAB devices) and follow a centralized, detailed protocol for DNA extraction, library preparation, and sequencing [7].

Bioinformatic Processing and Analysis

- Pipeline Execution: The same dataset of raw sequencing files (FASTQ) is processed independently through each pipeline (DADA2, MOTHUR, QIIME2) using default or author-recommended parameters [14].

- Data Output Alignment: To enable direct comparison, the filtered sequences from each pipeline are typically aligned against a common taxonomic reference database, such as SILVA or Greengenes [1] [2].

- Comparative Metrics: The following outcomes are systematically compared across pipelines:

- Sensitivity and Specificity: The number of expected species/strains correctly identified versus spurious taxa introduced, as measured using mock community data [14].

- Taxonomic Composition: Relative abundances of major phyla and genera in biological samples [2].

- Alpha and Beta Diversity: Metrics of within-sample and between-sample diversity [14].

- Reproducibility of Key Findings: Consistency in identifying primary biological drivers (e.g., the effect of a pathogen like H. pylori) [1].

Visualizing the Comparative Analysis Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the standardized workflow for a rigorous pipeline comparison study.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Reproducible Microbiome Research

| Item | Function in Research | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Microbial Communities (SynComs) | Defined mixtures of known bacterial strains that serve as a controlled ground truth for validating bioinformatic pipelines and laboratory protocols [7]. | A 17-member SynCom from a grass rhizosphere was used to test the reproducible assembly of microbiomes across five laboratories [7]. |

| Fabricated Ecosystem (EcoFAB) Devices | Standardized, sterile laboratory habitats that minimize environmental variability, enabling highly reproducible studies of plant-microbe interactions [7]. | EcoFAB 2.0 devices were used in a ring trial to ensure consistent plant growth and microbiome assembly across different research sites [7]. |

| Mock Community Standards | Commercially available genomic DNA from a defined set of microorganisms, used to verify sequencing accuracy and bioinformatic classification [18]. | The ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standard is used to confirm technical reproducibility in sequencing runs [18]. |

| Reference Databases (SILVA, Greengenes) | Curated collections of rRNA sequences that are essential for the taxonomic assignment of sequences processed by any pipeline [1]. | Alignment of sequences to different databases (SILVA vs. Greengenes) had only a limited impact on taxonomic assignments in a gastric microbiome study [1]. |

| Negative Controls | Sample-free controls (e.g., extraction blanks, no-template PCR controls) that are crucial for identifying and removing contaminating DNA sequences, especially in low-biomass studies [18]. | Used with the 'decontam' R package to identify and filter out reagent-derived contaminants in human milk microbiome data [18]. |

The evidence demonstrates that robust bioinformatics pipelines like DADA2, MOTHUR, and QIIME2 can generate reproducible and comparable results for core biological questions when applied to the same dataset [1]. This consistency is crucial for interpreting studies and underscores the broader applicability of microbiome analysis in clinical research. However, analytical variability in relative abundance estimates persists and is sufficient to prevent direct quantitative comparisons between studies that used different processing workflows [2].

To overcome this barrier and enhance clinical translation, the field is moving toward greater standardization and the adoption of artificial intelligence (AI) tools [17]. The future of credible clinical inferences in microbiome research depends on rigorous, reproducible methodologies that integrate multi-omics approaches and iterative experiments across diverse model systems [19] [17]. By adhering to standardized protocols, using common reagents and controls, and transparently reporting bioinformatic workflows, researchers can break the reproducibility barrier and accelerate the translation of microbiome insights into clinical diagnostics and therapies.

The analysis of microbial communities through 16S rRNA gene sequencing has become a fundamental tool in microbial ecology, human health research, and therapeutic development. A bioinformatic pipeline transforms raw sequencing data into meaningful ecological metrics through a structured sequence of computational processes. The reproducibility and accuracy of these pipelines are paramount for generating reliable, comparable results across studies. This guide provides an objective comparison of three widely used bioinformatics platforms—DADA2, MOTHUR, and QIIME2—focusing on their performance in processing raw sequences to generate ecological metrics, with supporting experimental data from comparative studies.

The ongoing debate regarding pipeline selection often centers on their methodological approaches: DADA2 and QIIME2 (which incorporates DADA2) typically infer amplicon sequence variants (ASVs), while MOTHUR traditionally clusters sequences into operational taxonomic units (OTUs). ASVs are resolved to single-nucleotide differences, offering higher resolution, whereas OTUs bin sequences with typically less than 3% variance [2]. Understanding the components and performance of these tools is crucial for researchers making informed decisions that affect downstream biological interpretations.

Pipeline Architecture and Key Components

A standardized bioinformatic pipeline for 16S rRNA amplicon analysis consists of several sequential stages, each with distinct computational goals. The architecture is largely consistent across platforms, though implementation details and algorithmic approaches vary significantly.

Diagram 1: Bioinformatic Pipeline Workflow. The generalized workflow for 16S rRNA amplicon analysis shows the key stages from raw data to ecological metrics, with platform-specific implementations for the denoising/clustering step.

The key components of a robust bioinformatic pipeline include [20]:

Data Collection and Preprocessing: Gathering raw sequencing data (FASTQ files) and associated metadata. Preprocessing involves quality checks, primer removal, and filtering to ensure data accuracy. Tools like FastQC and BBduk.sh are often employed [21].

Sequence Processing and Denoising/Clustering: This core step reduces sequencing errors and groups sequences into biological units. DADA2 uses a parametric error model to infer exact amplicon sequence variants (ASVs), while MOTHUR typically clusters sequences into OTUs based on a 97% similarity threshold [2] [22]. QIIME2 offers multiple denoising options, including DADA2 and Deblur [23].

Taxonomic Assignment: Filtered sequences are aligned against reference databases (e.g., SILVA, Greengenes, RDP) to classify organisms taxonomically [1] [21]. The choice of database can influence results, though studies show this impact may be limited compared to pipeline choice [1].

Diversity Analysis and Ecological Metrics: This includes calculating alpha-diversity (within-sample diversity) and beta-diversity (between-sample diversity) metrics, producing the final ecological interpretations [24] [21].

Visualization and Reporting: Generating figures, tables, and interactive visualizations to communicate results effectively. Platforms differ in their visualization capabilities, with some offering integrated solutions like iMAP's web-based reports [21].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Experimental Data on Pipeline Reproducibility

A 2025 comparative study investigated the reproducibility of gastric mucosal microbiome composition across three bioinformatics packages (DADA2, MOTHUR, and QIIME2) applied by five independent research groups to the same dataset [1]. The dataset included 16S rRNA gene raw sequencing data from gastric biopsy samples of gastric cancer patients (n=40) and controls (n=39), with and without Helicobacter pylori infection.

Table 1: Reproducibility of Key Microbial Metrics Across Pipelines (2025 Study)

| Metric | DADA2 | MOTHUR | QIIME2 | Concordance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H. pylori Status Detection | Reproducible | Reproducible | Reproducible | High across all platforms |

| Microbial Diversity Patterns | Consistent | Consistent | Consistent | Comparable results |

| Relative Bacterial Abundance | Reproducible | Reproducible | Reproducible | Minor quantitative differences |

| Impact of Taxonomic Database (SILVA vs. Greengenes) | Limited | Limited | Limited | Minimal effect on outcomes |

The study concluded that independent of the applied protocol, H. pylori status, microbial diversity and relative bacterial abundance were reproducible across all platforms, although differences in performance were detected [1]. This demonstrates that robust pipelines can generate comparable results, crucial for interpreting studies and underscoring the broader applicability of microbiome analysis in clinical research.

Quantitative Output Comparisons

A 2020 study provided a direct quantitative comparison of four pipelines (QIIME2, Bioconductor, UPARSE, and MOTHUR) run on two operating systems, analyzing 40 human stool samples [2]. The research revealed important differences in output characteristics.

Table 2: Quantitative Output Comparison Across Pipelines (2020 Study)

| Pipeline | Analysis Type | Feature Units | Relative Abundance of Bacteroides* | OS Dependency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QIIME2 | ASV-based | Single-nucleotide resolution | 24.5% | None (identical Linux vs. Mac) |

| Bioconductor | ASV-based | Single-nucleotide resolution | 24.6% | None (identical Linux vs. Mac) |

| UPARSE (Linux) | OTU-based | 97% similarity clusters | 23.6% | Minimal differences |

| UPARSE (Mac) | OTU-based | 97% similarity clusters | 20.6% | Minimal differences |

| MOTHUR (Linux) | OTU-based | 97% similarity clusters | 22.2% | Minimal differences |

| MOTHUR (Mac) | OTU-based | 97% similarity clusters | 21.6% | Minimal differences |

*The difference in relative abundance was statistically significant (p < 0.001), demonstrating that pipeline choice affects quantitative estimates [2].

The study found that while taxa assignments were consistent at both phylum and genus level across all pipelines, statistically significant differences emerged in relative abundance estimates for all phyla (p < 0.013) and most abundant genera (p < 0.028) [2]. This indicates that studies using different pipelines cannot be directly compared without appropriate normalization procedures.

Computational Efficiency and Practical Implementation

Regarding computational performance, cloud-based implementations demonstrate significant efficiency gains. One study developed a microbiome analysis pipeline using Amazon Web Services (AWS) that successfully processed 50 gut microbiome samples within 4 hours at a cost of approximately $0.80 per hour for a c4.4xlarge EC2 instance [24]. This highlights how cloud computing can provide accessible, scalable resources for pipeline implementation.

The integration of pipelines like iMAP (Integrated Microbiome Analysis Pipeline) demonstrates efforts to create more user-friendly solutions that wrap functionalities for metadata profiling, quality control, sequence processing, classification, and diversity analysis while generating web-based progress reports [21]. Such integrated approaches enhance reproducibility and accessibility for researchers with varying computational expertise.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Testing Protocols

To ensure fair comparisons between pipelines, researchers have developed standardized testing methodologies. The 2025 reproducibility study employed this protocol [1]:

- Sample Selection: 79 gastric biopsy samples (40 GC patients, 39 controls) with varying H. pylori status

- Sequencing Parameters: 16S rRNA gene (V1-V2 regions) raw sequencing data

- Analysis Groups: Five independent research groups applying their preferred protocols

- Comparison Metrics: H. pylori detection, alpha/beta diversity measures, taxonomic composition

- Database Alignment Testing: Filtered sequences aligned to RDP, Greengenes, and SILVA databases

Another comparative analysis between QIIME2 and DADA2 implemented this reproducible workflow [25]:

Research Questions:

- How do ASV tables from QIIME2 (via q2-dada2) and standalone DADA2 differ in feature count and read depth?

- What are the computational time and resource usage differences?

- How does tool choice influence downstream ecological conclusions?

Evaluation Metrics:

- Feature count and read depth comparisons

- Computational efficiency and resource usage

- Alpha and beta diversity outcomes

- Taxonomic assignment consistency

Denoising Method Comparison Protocol

A detailed comparison between DADA2 and Deblur (another denoising algorithm available in QIIME2) highlights the importance of parameter optimization [23]:

- Dataset: Large avian cloacal swab 16S dataset (initial 30,761,377 sequences)

- Preprocessing: Primer removal with cutadapt within QIIME2

- DADA2 Parameters: Applied directly on unmerged paired-end sequences

- Deblur Parameters: Sequences merged using vsearch, quality filtered, then denoised

- Results: DADA2 yielded 21,637,825 sequences (15,042 features) vs. Deblur's 7,749,895 sequences (9,373 features)

- Key Finding: Despite different absolute numbers, downstream biological interpretations (beta diversity, taxonomic composition) were remarkably similar

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Pipeline Implementation

| Category | Item | Function/Purpose | Examples/Options |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wet Lab Reagents | DNA Extraction Kit | Isolates microbial DNA from samples | QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit [2] |

| PCR Amplification Reagents | Amplifies target 16S rRNA regions | Illumina 16S Metagenomic Sequencing Library Preparation protocol [2] | |

| Sequencing Chemicals | Generates raw sequence data | MiSeq v3 cartridge (Illumina) [2] | |

| Bioinformatic Tools | Quality Control Tools | Assesses read quality and filters artifacts | FastQC, BBduk.sh, Seqkit [21] |

| Denoising/Clustering Algorithms | Groups sequences into biological units | DADA2 (ASVs), MOTHUR (OTUs), Deblur [1] [23] | |

| Taxonomic Databases | Reference for classifying sequences | SILVA, Greengenes, RDP, EzBioCloud [1] [21] | |

| Statistical Analysis Platforms | Computes diversity metrics and statistics | R, Python, QIIME2, Bioconductor [2] [20] | |

| Computational Infrastructure | Cloud Computing Services | Provides scalable computational resources | Amazon Web Services (AWS) EC2 instances [24] |

| Workflow Management Systems | Ensures reproducibility and portability | Nextflow, Snakemake, Docker containers [21] | |

| Visualization Tools | Creates interpretable data representations | iTOL, RStudio, Tableau, Matplotlib [20] [21] |

The comparative analysis of DADA2, MOTHUR, and QIIME2 reveals a complex landscape where each platform offers distinct advantages. The 2025 reproducibility study demonstrates that robust pipelines generate broadly comparable biological conclusions when applied to the same dataset, particularly for major factors like H. pylori status and overall diversity patterns [1]. However, significant differences in relative abundance estimates highlight that quantitative comparisons across studies using different pipelines require caution [2].

For researchers selecting pipelines, consider these evidence-based recommendations:

- For highest resolution: DADA2 or QIIME2 with DADA2 plugin offer single-nucleotide resolution through ASVs [25] [26]

- For established methodologies: MOTHUR provides well-validated OTU-based approaches with extensive documentation [22]

- For modularity and integration: QIIME2 offers a comprehensive, plugin-based ecosystem with standardized outputs [1] [21]

- For clinical applications: Emerging tools like MetaScope show promise for enhanced species-level classification beyond traditional pipelines [26]

The reproducibility crisis in microbiome research can be mitigated by thorough documentation of pipeline parameters, use of standardized protocols when possible, and transparency about computational methods. Future developments in pipeline harmonization and validation against mock communities will further enhance the reliability and comparability of microbiome studies across the research community.

From Theory to Practice: Implementing DADA2, QIIME2, and MOTHUR Pipelines

A Step-by-Step Guide to the DADA2 Workflow for Error-Corrected ASVs

In the field of microbiome research, the analysis of 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing data has been revolutionized by high-resolution techniques that infer amplicon sequence variants (ASVs). DADA2 stands as a prominent algorithm within this category, offering a denoising-based approach that provides a higher-resolution alternative to traditional operational taxonomic unit (OTU) methods [27]. This guide details the DADA2 workflow, frames it within the critical context of pipeline reproducibility, and objectively compares its performance against other widely used bioinformatics platforms like QIIME2 and mothur, providing researchers with the data needed to select the most appropriate tool for their microbiome studies.

Section 1: The DADA2 Workflow - A Step-by-Step Protocol

The DADA2 pipeline transforms raw, demultiplexed FASTQ files into a refined ASV table, which records the number of times each exact amplicon sequence variant was observed in each sample [3]. The following diagram outlines the core steps of this workflow.

- Step 1: Inspect Read Quality Profiles. The workflow begins by visualizing the quality profiles of the forward and reverse reads using the

plotQualityProfilefunction. This critical step determines the trimming parameters by identifying positions where read quality significantly deteriorates. For example, in a common 2x250 MiSeq protocol, forward reads might be truncated at position 240 and reverse reads at position 160 [3]. - Step 2: Filter and Trim Reads. The

filterAndTrimfunction applies the parameters determined in Step 1. Standard filtering parameters includemaxN=0(DADA2 requires no Ns),truncQ=2,rm.phix=TRUEto remove PhiX spike-in reads, andmaxEE=2, which sets the maximum number of "expected errors" allowed in a read, providing a superior filtering approach than averaging quality scores [3]. - Step 3: Learn Error Rates. DADA2 uses a novel algorithm to model the errors introduced during amplicon sequencing. The

learnErrorsfunction learns this error model from the data itself, which is subsequently used to infer the true biological sequences in the sample with high accuracy [27] [3]. - Step 4: Dereplicate Sequences. The

derepFastqfunction condenses the data by combining identical sequences, reducing computation time for the core sample inference algorithm [3]. - Step 5: Infer Sample Composition. The core

dadafunction applies the error model to the dereplicated data. It differentiates true biological sequence variants from spurious ones caused by sequencing errors, thereby inferring the exact amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) present in each sample [27]. - Step 6: Merge Paired Reads. For paired-end data, the

mergePairsfunction combines the forward and reverse reads after they have been denoised, creating fully overlapping, contiged sequences. A minimum overlap of 20 nucleotides is typical, and the function can also screen for spurious merges [3]. - Step 7: Construct ASV Table. The

makeSequenceTablefunction creates the final ASV table—a matrix with samples as columns and the inferred ASVs as rows, where each entry is the number of times that ASV was observed in that sample. This table is a higher-resolution analogue of the traditional OTU table [3]. - Step 8: Remove Chimeras. The final step involves identifying and removing chimeric sequences using

removeBimeraDenovo. Chimeras are artificial sequences formed from two or more biological sequences during PCR and are crucial to remove for obtaining reliable ASV data [27].

Section 2: Experimental Protocols for Pipeline Comparison

To objectively benchmark DADA2 against other pipelines, researchers often employ mock microbial communities, where the true composition is known. The protocol below, derived from a 2025 benchmarking study, illustrates a standardized methodology [28].

Mock Community Experiment Protocol:

- Sample Source: Utilize a complex mock community, such as the HC227 community comprising genomic DNA from 227 bacterial strains across 197 species [28].

- Sequencing: Amplify the V3-V4 or V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene and sequence on an Illumina MiSeq platform in a 2x300 bp paired-end run [28].

- Data Preprocessing:

- Quality Check: Use FastQC for initial sequence quality assessment.

- Primer Stripping: Remove primer sequences using tools like

cutPrimers. - Read Merging & Trimming: Merge paired-end reads and perform length trimming.

- Quality Filtering: Discard reads with ambiguous characters and apply a stringent maximum expected error threshold [28].

- Pipeline Analysis: Process the unified, preprocessed data through multiple bioinformatics pipelines, including DADA2, UPARSE, and mothur, using their standard parameters [28].

- Output Comparison: Compare the pipelines' outputs (ASVs or OTUs) against the known reference sequences of the mock community. Key metrics include error rate, over-splitting (generating multiple variants for one strain) vs. over-merging (grouping distinct strains into one unit), and the accuracy of the inferred microbial composition and diversity [28].

Section 3: Performance Comparison of Microbiome Pipelines

The following tables summarize key quantitative findings from independent comparative studies, evaluating DADA2, QIIME2 (which can use DADA2 as a plugin), UPARSE, and mothur.

Table 1: Algorithmic Comparison of Major 16S rRNA Analysis Pipelines

| Pipeline | Core Method | Primary Output | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DADA2 | Denoising; models sequencing errors to infer biological sequences [27]. | ASVs (Exact Sequence Variants) [27]. | Single-nucleotide resolution; high sensitivity; produces consistent, reproducible ASVs across studies [28]. | Can suffer from over-splitting of non-identical 16S rRNA gene copies within a single strain [28]. |

| QIIME2 | Modular platform; can utilize DADA2, Deblur, or other plugins [29]. | ASVs (when using DADA2/Deblur). | Comprehensive, user-friendly platform; tracks full data provenance; extensive plugin ecosystem [29]. | Performance depends on the chosen denoising/clustering plugin. |

| UPARSE | Greedy clustering of sequences based on identity [28]. | OTUs (97% identity). | Lower error rates in clusters; less over-splitting; efficient performance [28]. | Uses fixed similarity cutoff, which may obscure real biological variation; prone to over-merging distinct taxa [28]. |

| mothur | Distance-based clustering (e.g., average neighbor, Opticlust) [28]. | OTUs (97% identity). | Well-established, extensive SOPs; intensive quality filtering [21]. | Similar to UPARSE, relies on fixed clustering thresholds [28]. |

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics from Mock Community Studies

| Performance Metric | DADA2 | UPARSE | mothur | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resemblance to Intended Community | High (One of the closest) | High (One of the closest) | Moderate | Analysis of the HC227 mock community (227 strains) using PE reads [28]. |

| Error Tendency | Over-splitting [28] | Over-merging [28] | Over-merging [28] | Evaluation of splitting/merging behavior against known reference sequences [28]. |

| Relative Abundance Accuracy (Bacteroides) | 24.5% [2] | 20.6% - 23.6% [2] | 21.6% - 22.2% [2] | Comparison on human stool samples; all pipelines showed statistically significant differences in abundance estimates [2]. |

| Output Consistency Across OS | N/A | Minimal differences [2] | Minimal differences [2] | QIIME2 and Bioconductor (which runs DADA2) provided identical outputs on Linux and Mac OS [2]. |

Table 3: Key Resources for Implementing the DADA2 Workflow

| Resource Name | Type | Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| R / RStudio | Software Environment | The primary environment for installing and running the DADA2 R package and associated analysis scripts [3]. |

| dada2 R Package | R Library | Implements the core denoising, merging, and chimera removal functions of the workflow [3]. |

| SILVA / Greengenes | Reference Database | Curated databases of 16S rRNA sequences used for assigning taxonomy to the inferred ASVs [21]. |

| Mock Community | Control Reagent | A sample composed of known microbial strains, essential for validating and benchmarking the performance of the bioinformatics pipeline [28]. |

| Amazon EC2 (c4.4xlarge) | Computational Resource | A cloud-based virtual server instance suitable for high-performance computation, capable of processing 50 gut microbiome samples in ~4 hours [24]. |

| FastQC | Bioinformatics Tool | Provides initial quality control reports for raw FASTQ files, informing trimming and filtering parameters [28]. |

Section 5: Discussion: Reproducibility in Microbiome Bioinformatics

The choice of bioinformatics pipeline significantly impacts research outcomes, as different tools can yield variations in taxonomic assignment and relative abundance estimates [2]. This underscores a central challenge in microbiome research: ensuring reproducibility and cross-study comparability.

DADA2 contributes to reproducibility by generating exact ASVs that can be directly compared across studies without re-clustering, unlike traditional OTUs [27]. Furthermore, when used within integrated platforms like QIIME2, which automatically tracks all parameters and steps (provenance), the entire analytical process becomes more transparent and repeatable [29]. For the highest level of reproducibility, researchers are increasingly adopting containerized technologies like Docker, which package the entire analysis environment (software, dependencies, and code), and leveraging cloud computing platforms like Amazon Web Services (AWS), which provide standardized, powerful computational resources [24] [21].

DADA2 provides a powerful, denoising-based workflow for achieving high-resolution insights into microbial communities via ASVs. While it excels in sensitivity and resolution, benchmarking shows it has a characteristic tendency towards over-splitting compared to the over-merging of OTU-based methods like UPARSE. The selection of an analytical pipeline should therefore be a deliberate decision, informed by the specific research question and the documented performance characteristics of each tool. To ensure robust and reproducible science, researchers should validate their chosen pipeline with mock communities, thoroughly document all parameters, and leverage modern computational solutions that enhance consistency and transparency in microbiome data analysis.

In the pursuit of reproducible microbiome bioinformatics, the choice of processing tools within a pipeline is paramount. For 16S rRNA marker gene data, two critical and divergent steps are the bioinformatic correction of sequencing errors (denoising) to define biological sequences and the subsequent taxonomic classification of those sequences. Within the widely adopted QIIME 2 ecosystem, DADA2 and Deblur represent the primary approaches for denoising, transforming raw sequencing reads into amplicon sequence variants (ASVs). Following this, the q2-feature-classifier plugin, often used with pre-trained classifiers, assigns taxonomy to these ASVs. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of these core QIIME 2 plugins, framing their performance within a broader thesis on the reproducibility of microbiome bioinformatics pipelines. Understanding the operational differences, outputs, and optimal use cases for DADA2 and Deblur, as well as the resources available for taxonomic assignment, empowers researchers to make informed decisions that enhance the reliability and interpretability of their data.

DADA2 vs. Deblur: A Conceptual and Methodological Comparison

DADA2 and Deblur achieve the same core goal—denoising marker gene sequences to resolve fine-scale variation—but through fundamentally different algorithms and workflows.

Core Algorithmic Differences

- DADA2: Employs a parametric error model that learns specific error rates from the dataset itself. It models substitutions as a function of the transition/transversion rate and the sequence quality scores, treating the denoising problem as a statistical inference task to distinguish true biological sequences from erroneous ones [30].

- Deblur: Uses a positive, non-parametric filtering approach based on read abundance profiles. It operates under the principle that true sequences will be observed multiple times, while error-containing reads will be rare variants of more abundant sequences. Deblur aggressively removes these low-frequency variants to arrive at the true biological sequences [31].

Workflow and Input Requirements

A key practical difference lies in their handling of sequence length and read merging.

DADA2 internally manages read merging, while Deblur requires pre-joined sequences [31] [23].

- DADA2: For paired-end reads, the

denoise-pairedaction processes forward and reverse reads separately before merging them post-denoising. It does not require all output sequences to be the same length, accepting a range of sequence lengths in its output [31]. - Deblur: The

denoise-16Saction requires all input sequences to be of a uniform length, specified by the--p-trim-lengthparameter. For paired-end data, this necessitates an upstream read-joining step (e.g., usingq2-vsearch) and often an additional quality-filtering step before denoising can begin [31] [23].

Experimental Performance and Data Output Comparison

A direct application of both denoisers to the same dataset reveals significant differences in output, which can impact downstream biological interpretation.

Empirical Case Study: Avian Cloacal Swab Dataset

In a comparative analysis, both DADA2 and Deblur were run on a large 16S dataset from avian cloacal swabs containing an initial 30,761,377 sequences [23]. The table below summarizes the key quantitative outcomes from this experiment.

Table 1: Denoising Output Comparison on a 16S Avian Cloacal Swab Dataset [23]

| Metric | DADA2 | Deblur |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Sequences | 30,761,377 | 30,761,377 |

| Final Non-Chimeric Sequences | 21,637,825 | 7,749,895 |

| Final Features (ASVs) | 15,042 | 9,373 |

| Sequence Retention Rate | ~70.3% | ~25.2% |

| Feature Characteristics | Varying lengths (85.6% at 253bp) | All sequences 253bp |

Interpretation of Discrepancies and Downstream Consistency

- Sequence Retention: DADA2 retained nearly three times as many sequences as Deblur. This dramatic difference is attributed to Deblur's more aggressive filtering, which may discard more sequences, including potentially real low-abundance biological variants [23].

- Feature Resolution: DADA2 recovered substantially more ASVs (~15k vs. ~9k), suggesting a higher resolution of sequence variants. The length distribution of DADA2 features showed that while most (85.6%) were the expected 253bp, a significant minority were shorter or longer, which Deblur's uniform length requirement would automatically exclude [23].

- Biological Concordance: Despite the large discrepancies in absolute numbers, the study noted that downstream beta-diversity (UniFrac PCoA) and phylum-level composition results were highly similar between the two methods. This indicates that while the fine-scale ASV lists differ, the broader ecological conclusions can be robust across denoising choices [23].

Taxonomic Classification within QIIME 2

After generating ASVs, the next critical step is assigning taxonomy using the q2-feature-classifier plugin. This typically involves aligning sequences against a curated reference database.

The Taxonomic Classification Workflow

The process generally involves a pre-trained classifier that matches your sequences to a reference database. QIIME 2 provides several such classifiers, tailored to different genes and regions [32].

The standard taxonomic classification workflow in QIIME2 uses a pre-trained Naive Bayes classifier [32].

Available Pre-trained Classifiers

The choice of reference database is critical. Researchers must select a classifier compatible with their QIIME 2 version and trained on the appropriate gene region.

Table 2: Selected Pre-trained Naive Bayes Classifiers for QIIME 2 (2024.5 - Present) [32]

| Reference Database | Target Gene Region | UUID (for download) | Key Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Silva 138 99% OTUs | Full-length / 515F/806R | 70b4b5f4-8fce-40bd-b508-afacbc12a5ed |

Species-level taxonomy may be unreliable |

| Greengenes2 2024.09 | Full-length / 515F/806R | 49ccfb0a-155d-404b-80b4-818d2aeb53b2 |

Successor to Greengenes 13_8 |

| GTDB r220 | Full-length | 5d5461cc-6a51-434b-90ab-040f388e4221 |

Based on Genome Taxonomy Database |

Experimental Protocols for Reproducible Analysis

To ensure reproducibility, detailed methodologies for key steps are essential.

Protocol A: Denoising Paired-End Reads with DADA2

This protocol is adapted from the "Moving Pictures" tutorial and community best practices [30] [31] [23].

- Import Data: Import demultiplexed paired-end FASTQs using a manifest file and

qiime tools importwith typeSampleData[PairedEndSequencesWithQuality]. - Primer Removal: Trim sequencing adapters and primers using

qiime cutadapt trim-paired. - Denoise: Run

qiime dada2 denoise-paired. Critical parameters include:--i-demultiplexed-seqs: Input trimmed sequences.--p-trunc-len-fand--p-trunc-len-r: Positions to truncate forward and reverse reads based on quality profile inspection. Omit to disable truncation.--p-trim-left-fand--p-trim-left-r: Number of bases to remove from the 5' start of reads, often to remove primer remnants.--p-n-threads: Number of cores to use for parallel processing.

- Outputs: The action produces three key artifacts: a

FeatureTable[Frequency],FeatureData[Sequence](representative sequences), and aSampleData[DADA2Stats]denoising statistics file.

Protocol B: Denoising with Deblur for Single-End Reads

This protocol requires pre-joined or single-end reads of a uniform length [31] [23].

- Import & Join Reads (if paired-end): For paired-end data, first join reads using

qiime vsearch join-pairs, then filter for quality withqiime quality-filter q-score-joined. - Denoise: Run

qiime deblur denoise-16S(for 16S data) ordenoise-other(for other markers).--i-demultiplexed-seqs: Input the quality-filtered, joined sequences.--p-trim-length: The mandatory length to which all sequences will be trimmed. Use-1to disable, but this is not recommended.

- Outputs: Similar to DADA2, this generates a

FeatureTable[Frequency],FeatureData[Sequence], and aSampleData[DeblurStats]stats file.

Protocol C: Taxonomic Assignment with a Pre-trained Classifier

This is a standardized workflow for assigning taxonomy to your representative sequences [32].

- Classifier Selection: Download a pre-trained classifier compatible with your QIIME 2 version and gene region from the QIIME 2 Data Resources page.

- Run Classification: Execute

qiime feature-classifier classify-sklearn.--i-reads: Your representative sequences (FeatureData[Sequence]).--i-classifier: The pre-trained classifier artifact.--o-classification: The output taxonomy assignments.

- Output: The result is a

FeatureData[Taxonomy]artifact, which can be merged with the feature table for downstream analyses and visualizations, such as creating bar plots.

Table 3: Key Resources for QIIME2 Amplicon Analysis

| Resource Name / Plugin | Category | Primary Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| q2-dada2 | Denoising Plugin | Denoises single-end, paired-end, and PacBio CCS reads into ASVs using a parametric error model [31] [33]. |

| q2-deblur | Denoising Plugin | Denoises quality-filtered single-end reads into ASVs using positive abundance-aware filtering [31] [33]. |

| q2-feature-classifier | Classification Plugin | Assigns taxonomy to feature sequences using methods like classify-sklearn (Naive Bayes) against a reference database [34] [33]. |

| q2-demux / q2-cutadapt | Preprocessing Plugin | Demultiplexes raw sequence data and removes primers/adapters [30] [31]. |

| q2-vsearch | Utility Plugin | Joins paired-end reads (pre-Deblur) and performs reference-based OTU clustering and chimera filtering [30] [33]. |

| Silva / Greengenes2 / GTDB | Reference Database | Curated collections of reference sequences and taxonomies used for training classifiers and taxonomic assignment [32]. |

| Pre-trained Classifiers | Data Resource | Ready-to-use .qza files containing a classifier and reference database, version-matched for immediate use with q2-feature-classifier [32]. |

The choice between DADA2 and Deblur is not a matter of one being universally superior, but rather which is more appropriate for a given study's goals and data type. DADA2 offers a more integrated workflow for paired-end data, does not impose a uniform sequence length, and typically yields a higher resolution of ASVs, which may be crucial for strain-level analyses. Deblur provides a stringent, uniform-length approach that can be advantageous for consistency and may reduce the potential for spurious, over-split variants. Critically, empirical evidence suggests that while the absolute numbers of sequences and ASVs can differ dramatically, the broader ecological patterns often converge [23]. This convergence is reassuring for the reproducibility of high-level biological findings. Ultimately, researchers should align their tool choice with their specific research questions, declare their bioinformatic parameters with transparency, and utilize version-controlled, pre-trained resources like taxonomic classifiers to ensure that their microbiome analyses are both robust and reproducible.

The MOTHUR Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) for OTU Clustering

Operational Taxonomic Unit (OTU) clustering is a foundational step in 16S rRNA gene analysis, grouping sequences based on similarity to reduce data complexity and infer taxonomic units. The MOTHUR platform provides multiple algorithms for this critical bioinformatics task, with its Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) representing a comprehensive workflow for processing amplicon sequence data from raw reads through community analysis [35]. MOTHUR primarily employs traditional OTU-based approaches where sequences are clustered at a 97% similarity threshold, contrasting with more recent Amplicon Sequence Variant (ASV) methods that resolve sequences to single-nucleotide differences [13]. This clustering process transforms raw sequence data into biological insights about microbial community structure, diversity, and composition, forming the basis for downstream ecological analyses.

MOTHUR's Clustering Algorithms and Methodologies

Core Clustering Methods

MOTHUR implements several clustering algorithms, each with distinct approaches to defining OTU boundaries:

- OptiClust (opti): The default algorithm that assembles OTUs using metrics to determine clustering quality through an iterative optimization process that seeks to maximize the similarity within clusters and minimize similarity between clusters [36].

- Nearest neighbor (nearest): Implements a liberal clustering approach where each sequence within an OTU is at most X% distant from the most similar sequence in the OTU, potentially creating larger, more inclusive OTUs [36].

- Furthest neighbor (furthest): Employs a conservative strategy requiring all sequences within an OTU to be at most X% distant from all other sequences in the same OTU, resulting in smaller, more stringent OTUs [36].

- Average neighbor (average): Represents a middle ground between nearest and furthest neighbor approaches, balancing the trade-offs between the two extreme clustering philosophies [36].

- Abundance-based greedy clustering (agc) and Distance-based greedy clustering (dgc): Greedy clustering algorithms that provide alternative heuristic approaches to OTU formation [36].

- Unique (unique): Creates a list file where every unique sequence is assigned to its own OTU, effectively generating Amplicon Sequence Variants without clustering [36].

The OptiClust Advantage

OptiClust represents MOTHUR's sophisticated clustering implementation, using an algorithm that compares different clustering solutions through an iterative process. It evaluates clustering quality using metrics including sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and the Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) [36]. The algorithm runs through multiple iterations, with output displaying progressive refinement of these metrics until optimal clustering is achieved. When using OptiClust, researchers should cite the dedicated publication by Westcott and Schloss (2017) that established its improved performance over traditional methods [36].

OTU Fitting with Cluster.fit

For projects requiring consistent OTU definitions across datasets, MOTHUR offers the cluster.fit command with two operational modes:

- Closed reference fitting: Forces all reads into existing OTU definitions, discarding any sequences that cannot be matched to reference OTUs [37].

- Open reference fitting: Allows unmatched reads to form new OTUs alongside the reference OTUs, providing flexibility while maintaining consistency for the majority of sequences [37].

This functionality is particularly valuable for longitudinal studies and multi-study comparisons where maintaining consistent OTU definitions across sampling events or research projects is methodologically critical.

Performance Comparison with Alternative Pipelines

Methodological Comparison Framework

Recent benchmarking studies have evaluated MOTHUR against other popular bioinformatics pipelines using both mock communities with known composition and large clinical datasets to assess real-world performance. These comparisons typically evaluate pipelines across multiple dimensions including sensitivity (ability to detect true positives), specificity (ability to avoid false positives), and quantitative accuracy in estimating microbial abundances [13]. The fundamental methodological division lies between OTU-based approaches like MOTHUR's traditional clustering and ASV-based methods like DADA2 and UNOISE3 that resolve exact sequences without clustering.

Table 1: Pipeline Methodological Approaches and Characteristics

| Pipeline | Clustering Unit | Primary Method | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOTHUR | OTU | Distance-based clustering (OptiClust) | Multiple algorithm options; alignment-based; comprehensive workflow |

| QIIME-uclust | OTU | Heuristic clustering | Older approach; produces spurious OTUs [13] |

| USEARCH-UPARSE | OTU | Greedy clustering | Good performance but lower specificity than ASV methods [13] |

| DADA2 | ASV | Statistical error correction | Highest sensitivity; decreased specificity [13] |

| Qiime2-Deblur | ASV | Error correction | Intermediate sensitivity/specificity balance [13] |

| USEARCH-UNOISE3 | ASV | Error correction | Best balance between resolution and specificity [13] |

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Independent comparative studies provide empirical data on how MOTHUR performs relative to other pipelines. A 2020 analysis by Prodan et al. evaluated six bioinformatic pipelines on a mock community with known composition and a large fecal sample dataset (N=2170), revealing important performance differences [13].

Table 2: Performance Comparison Across Bioinformatics Pipelines

| Pipeline | Sensitivity | Specificity | Spurious OTUs/ASVs | Alpha-Diversity Inflation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOTHUR | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Minimal |

| QIIME-uclust | Moderate | Low | High | Inflated [13] |

| USEARCH-UPARSE | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Minimal |

| DADA2 | Highest | Lower | Moderate | Minimal |

| Qiime2-Deblur | High | High | Low | Minimal |

| USEARCH-UNOISE3 | High | Highest | Lowest | Minimal |

These performance characteristics directly impact biological interpretations. For instance, the tendency of QIIME-uclust to generate spurious OTUs and inflate alpha-diversity measures could lead to erroneous ecological conclusions about microbial diversity [13]. MOTHUR demonstrates reliable performance with moderate sensitivity and specificity, producing fewer spurious OTUs than QIIME-uclust while offering more traditional OTU-based analysis compared to ASV methods.

Reproducibility Across Platforms

A critical consideration for clinical and translational research is method reproducibility. A 2025 study comparing microbiome analysis pipelines across five independent research groups found that MOTHUR, DADA2, and QIIME2 generated comparable results for major biological patterns despite differences in their underlying algorithms [1]. Specifically, Helicobacter pylori status, microbial diversity, and relative abundance of major taxa were reproducibly identified across all platforms when applied to the same gastric biopsy dataset [1]. This reproducibility across independent implementations underscores the robustness of well-established pipelines like MOTHUR for identifying key biological signals.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard MOTHUR SOP Workflow

The MOTHUR SOP for MiSeq data represents a comprehensive protocol for processing 16S rRNA gene sequences from raw sequencing reads through OTU clustering and analysis [35]. The workflow proceeds through several methodical stages:

Figure 1: MOTHUR SOP workflow for OTU clustering and analysis.

Sequence Processing and Quality Control

The initial stages focus on sequence quality and data integrity:

- Make.contigs: Processes paired-end reads by extracting sequence and quality score data from FASTQ files, creating reverse complements of reverse reads, and joining reads into contigs using a quality-aware algorithm that resolves disagreements between forward and reverse reads [35].

- Alignment (align.seqs): Aligns sequences against a reference alignment (typically SILVA) using a positional homology approach to ensure accurate comparison across the targeted gene region [35] [38].

- Filtering (screen.seqs): Removes sequences that are too short, too long, or contain ambiguous base calls, followed by removal of redundant sequences to reduce computational burden [35].

- Chimera Removal: Identifies and removes PCR artifacts using algorithms like VSEARCH or ChimeraSlayer that detect chimeric sequences formed during amplification [35].

Distance Calculation and Clustering

The core OTU clustering process involves:

- Distance Matrix (dist.seqs): Calcules pairwise distances between aligned sequences, producing either column or phylip-formatted matrices that quantify sequence dissimilarity [36] [39].

- OTU Clustering (cluster): Groups sequences into OTUs using the selected algorithm (default: OptiClust) at a specified cutoff (typically 0.03, equivalent to 97% similarity) [36].

Benchmarking Methodologies

Comparative studies employ standardized evaluations to assess pipeline performance:

- Mock Community Analysis: Uses defined consortia of known bacterial strains (e.g., Microbial Mock Community B) with predetermined composition and abundance ratios to measure accuracy in taxonomic assignment and quantitative representation [13].

- Large Clinical Datasets: Applies pipelines to extensive sample collections (e.g., N=2170 in the HELIUS study) to evaluate performance on realistic, complex microbial communities and assess computational efficiency [13].

- Cross-Platform Validation: Implements identical datasets across multiple independent research groups to measure reproducibility and identify platform-specific biases [1].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Components

Computational Tools and Algorithms

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for MOTHUR OTU Clustering

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application in MOTHUR |

|---|---|---|

| SILVA Database | Reference alignment | Provides curated 16S rRNA sequence alignment for positional homology [35] [38] |

| RDP Training Set | Taxonomic classification | Enables Bayesian classification of sequences into taxonomic groups [35] |

| OptiClust Algorithm | OTU clustering | Default clustering method that optimizes OTU quality metrics [36] |

| VSEARCH | Chimera detection | Identifies and removes PCR artifacts from sequence data [35] |

| Distance Matrix | Sequence comparison | Quantifies pairwise differences between sequences for clustering [36] |

Critical Experimental Considerations

Successful implementation of MOTHUR OTU clustering requires attention to several methodological factors:

- Region Selection: The V4 region with 250bp paired-end reads provides optimal overlap and error correction; deviation from this standard region requires custom reference alignment using

pcr.seqswith specific start and end coordinates [38]. - Quality Control: Stringent filtering parameters including minimum length requirements, maximum homopolymer lengths, and minimum quality scores dramatically impact downstream results [35].

- Reference Alignment: Proper alignment using the SILVA database with region-specific trimming ensures positional homology across sequences, a critical requirement for accurate distance calculation [38].

- Algorithm Selection: Choice of clustering algorithm (OptiClust vs. traditional methods) affects OTU quality and biological interpretations, with OptiClust generally providing superior performance [36].

Implications for Microbiome Research Reproducibility