Navigating Microbiome Compositional Data Analysis: Overcoming CoDA Challenges for Robust Biomedical Insights

Microbiome sequence data are inherently compositional, with relative abundances constrained by a constant sum, leading to spurious correlations and analytical challenges if ignored.

Navigating Microbiome Compositional Data Analysis: Overcoming CoDA Challenges for Robust Biomedical Insights

Abstract

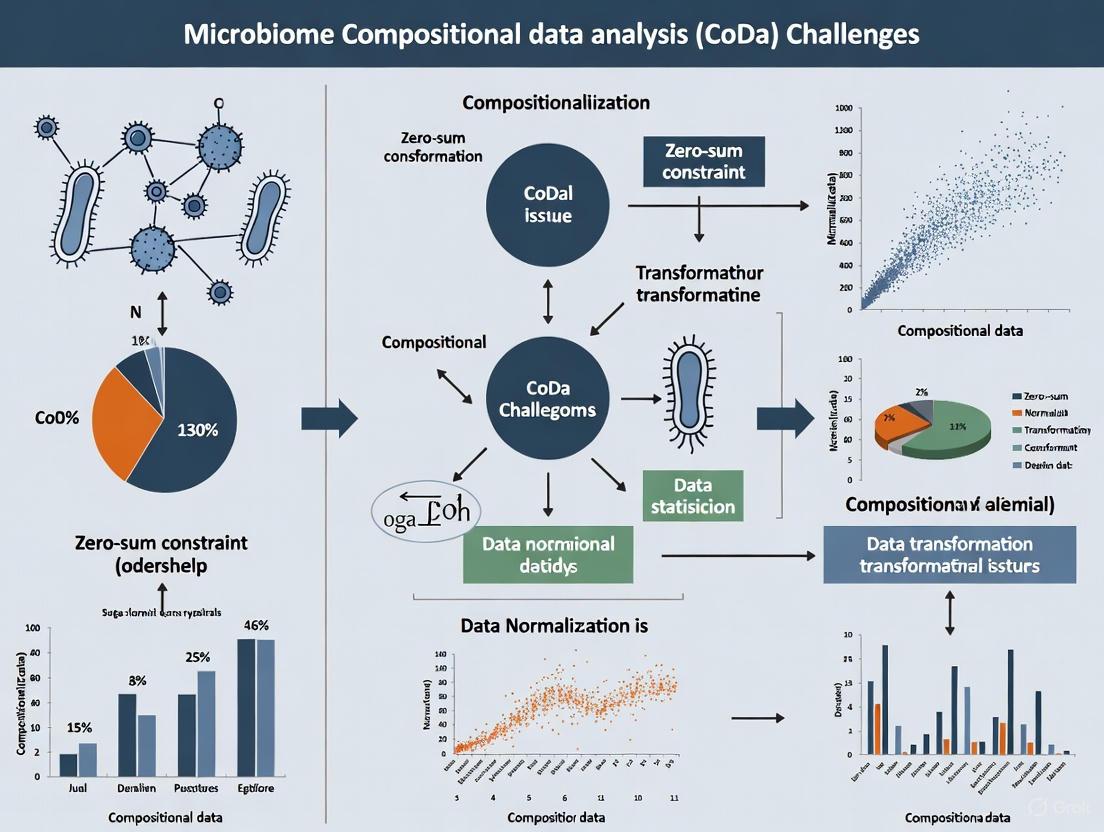

Microbiome sequence data are inherently compositional, with relative abundances constrained by a constant sum, leading to spurious correlations and analytical challenges if ignored. This comprehensive review explores Compositional Data Analysis (CoDA) fundamentals, tools, and challenges for researchers and drug development professionals. We cover foundational principles of compositional data, methodological approaches including log-ratio transformations and Bayesian models, troubleshooting strategies for zero-rich high-dimensional data, and validation frameworks for clinical translation. The article addresses critical gaps in handling microbiome data's unique properties while highlighting emerging applications in immunotherapy response prediction, disease diagnostics, and therapeutic development.

The Compositional Nature of Microbiome Data: Why Traditional Statistics Fail

In microbiome research, data derived from next-generation sequencing are inherently compositional. This means the data are vectors of non-negative elements (e.g., counts of microbial taxa) that are constrained to sum to a constant, such as 100% or one million reads for a sample normalized by total sequence count [1]. This "constant-sum constraint" is not a property of the microbial community itself but is an artifact of the measurement process. Since sequencing depth varies between samples, we must normalize the data, converting absolute counts into relative abundances to make samples comparable. Consequently, the absolute abundances of bacteria in the original sample cannot be recovered from sequence counts alone; we can only access the proportions of different taxa [1] [2].

This simple feature has profound implications. The components of the composition (the different microbial taxa) are not independent—they necessarily compete to make up the constant total. This leads to the "closure problem," where an increase in the measured proportion of one taxon forces an apparent decrease in the proportions of all others, even if their absolute abundances have not changed [1] [3]. This property violates the assumption of sample independence in many traditional statistical methods and can create spurious correlations, leading to biased and flawed biological inference [1] [4] [2].

Core Concepts: The FAQ

What is the "closure problem" in compositional data? The closure problem arises because all components in a composition are linked by the constant-sum constraint. When the absolute abundance of one microbe increases, its proportion of the total increases. To maintain the fixed total, the proportions of other microbes must decrease, even if their absolute abundances remain unchanged. This creates a negative bias in the covariance structure and makes the data appear to compete, which can be a mere artifact of the measurement scale rather than a true biological relationship [1] [3].

What are spurious correlations, and how does compositionality cause them? Spurious correlations are apparent statistical associations between variables that are not causally related but appear related due to the structure of the data or the analysis method [4]. In compositional data, spurious correlations inevitably arise from the shared denominator (the total sequence count). As noted by Karl Pearson over a century ago, comparing proportions haphazardly will produce such spurious correlations [1] [4].

Illustration: If you take three independent random variables, x, y, and z, they will be uncorrelated. However, if you form the ratios x/z and y/z, these two new ratios will exhibit a correlation, purely as an artifact of sharing the same divisor, z [4]. In a microbiome context, if two rare taxa (x and y) are independent, but a third, highly variable taxon (z) changes in abundance, the proportions of x and y will appear to correlate negatively with each other simply because they are both being "diluted" or "concentrated" by changes in z.

Why are traditional statistical methods problematic for compositional data? Standard statistical methods and correlation measures (e.g., Pearson correlation) assume data can vary independently in Euclidean space. Compositional data, however, reside in a constrained space known as the simplex, which has a different geometry (Aitchison geometry) [1]. Applying traditional methods to raw proportions or other normalized counts violates this fundamental assumption. It leads to inevitable errors in covariance estimates, making results unreliable and often uninterpretable [1] [2] [3]. This problem is particularly acute in high-dimensional, sparse microbiome datasets where the number of taxa far exceeds the number of samples [2].

Is this problem restricted to communities with only a few dominant taxa? No. While it has been suggested that compositional effects might be most severe in low-diversity communities (e.g., the vaginal microbiome), they pose a fundamental challenge to the analysis of any microbial community surveyed by relative abundance data, including the highly diverse gut microbiome [1].

A Troubleshooting Guide for Researchers

Problem: My analysis is revealing microbial correlations that may be spurious.

Diagnosis: You have applied correlation analysis (e.g., co-occurrence network analysis) directly to relative abundance data (proportions, percentages, or rarefied counts) without accounting for compositionality.

Solution: Adopt a Compositional Data Analysis (CoDa) framework centered on log-ratio transformations.

Detailed Methodology:

Replace Absolute Abundance Thinking with Relative Thinking: Shift your focus from "How much of microbe A is there?" to "How does the amount of microbe A compare to microbe B?" or "How does the amount of microbe A compare to a typical microbial community?" [1].

Apply a Log-Ratio Transformation: Transform your data to move from the constrained simplex space to the real Euclidean space, where standard statistical tools are valid. The three primary transformations are detailed in the table below [1] [5] [3].

Conduct Downstream Analysis: Use the transformed data for all subsequent statistical analyses, including ordination, clustering, correlation, and differential abundance testing.

Table 1: Core Log-Ratio Transformations for Microbiome Data

| Transformation | Acronym | Formula (for D parts) | Key Properties | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Additive Log-Ratio [1] [3] | ALR | ( alr(x) = \left[ \ln\frac{x1}{xD}, \ln\frac{x2}{xD}, ..., \ln\frac{x{D-1}}{xD} \right] ) | Simple; creates a real-valued vector. Asymmetric (depends on choice of denominator (x_D)). | Preliminary analysis; when a natural reference taxon exists. |

| Centered Log-Ratio [1] [5] | CLR | ( clr(x) = \left[ \ln\frac{x1}{g(x)}, \ln\frac{x2}{g(x)}, ..., \ln\frac{x_D}{g(x)} \right] ) where (g(x)) is the geometric mean of all parts. | Symmetric; preserves all parts. Results in a singular covariance matrix (parts sum to zero). | PCA; covariance-based analyses; computing Aitchison distance. |

| Isometric Log-Ratio [1] [5] | ILR | ( ilr(x) = [y1, y2, ..., y{D-1}] ) where (yi) are coordinates in an orthonormal basis built from balances. | Complex to define. Preserves isometric properties (distances and angles). | Most robust statistical analyses; when an orthonormal coordinate system is needed. |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the decision path for diagnosing and correcting compositional data problems.

Problem: My dataset contains many zeros, preventing log-ratio transformations.

Diagnosis: The logarithm of zero is undefined, and many microbial datasets are sparse (most taxa are absent in most samples).

Solution: Use robust methods for handling zeros.

Detailed Methodology:

- Identify the Nature of Zeros: Determine if zeros are "count zeros" (the taxon is truly absent) or "essential zeros" (the taxon is present but undetected due to low sequencing depth) [1].

- Apply a Replacement Strategy: Use specialized methods to impute zeros with small positive values. The zCompositions R package provides multivariate imputation methods for left-censored data (e.g., Bayesian-multiplicative replacement or other model-based approaches) under a compositional approach [1].

- Proceed with Transformation: After careful imputation, apply your chosen log-ratio transformation.

Problem: My experimental design may introduce confounding factors.

Diagnosis: The microbiome is highly sensitive to environmental and host factors, which can confound results and be misinterpreted as a compositional effect or vice versa.

Solution: Implement rigorous experimental controls.

Detailed Methodology:

- Document Extensive Metadata: Record all possible confounding factors such as age, diet, antibiotic use, geography, pet ownership, and host genetics [6] [7]. Treat these as independent variables in statistical models.

- Control for Batch Effects: For longitudinal studies, use the same batch of DNA extraction kits for all samples or extract DNA in a single batch to minimize technical variation [7].

- Account for Cage Effects in Animal Studies: House experimental and control groups in multiple, separate cages. In statistical analysis, treat "cage" as a random effect or blocking factor, as co-housing leads to microbial sharing [7].

- Include Proper Controls: Always run positive and negative controls (e.g., mock communities with known composition and blank extraction kits) to identify contamination, especially in low-biomass samples [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Computational Tools for CoDa Research

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Relevance to CoDA |

|---|---|---|

| CoDaPack Software [5] | A user-friendly, standalone software for compositional data analysis. | Performs ALR, CLR, and ILR transformations; includes PCA and other CoDa-specific analyses. Ideal for non-programmers. |

| R Statistical Software [3] | An open-source environment for statistical computing and graphics. | The primary platform for CoDa, with packages like zCompositions (zero imputation) and compositions or robCompositions for transformations and analysis [1]. |

| OMNIgene Gut Kit [7] | A non-invasive collection kit for stool samples that stabilizes microbial DNA at room temperature. | Ensures sample integrity during storage/transport, crucial for generating reliable data for downstream CoDa. |

| Mock Community [7] | A defined mix of microbial cells or DNA with known abundances. | Serves as a positive control to test the entire workflow, from DNA extraction to sequencing and bioinformatics, including the performance of CoDa transformations. |

| Standardized DNA Extraction Kit [7] | A consistent kit lot used for all extractions in a study. | Reduces batch-effect technical variation, which can interact with and exacerbate compositional effects. |

The compositional nature of microbiome sequencing data is an inescapable mathematical property, not a mere technical nuisance. Ignoring it guarantees that some findings will be spurious artifacts of the data structure rather than reflections of true biology. The path to robust inference requires a paradigm shift from an absolute to a relative perspective, implemented through the consistent use of log-ratio transformations and compositionally aware statistical methods. While challenges remain—particularly with data sparsity and the fundamental inability to recover absolute abundance from sequencing data alone—the tools and frameworks of Compositional Data Analysis provide the necessary foundation for valid and reliable conclusions in microbiome research.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does my beta-diversity analysis show different patterns when I use different distance metrics?

The choice of distance metric fundamentally changes how your data is compared because microbiome data is compositional. Bray-Curtis dissimilarity, a non-compositional metric, tends to emphasize differences driven primarily by the most abundant taxa. In contrast, Aitchison distance, a compositional metric, compares taxa through their abundance ratios and preserves the underlying overall compositional structure, providing a more balanced view that incorporates variation from both dominant and less abundant taxa [8]. For example, in human gut microbiome data, Bray-Curtis emphasized differences driven by dominant genera like Bacteroides and Prevotella, while Aitchison distance revealed a structure more strongly associated with individual subjects [8].

Q2: I keep getting errors when running CoDA-based analyses on my microbiome data. What could be causing this?

A common source of error is the presence of zeros in your dataset, as log-ratio transformations cannot be applied to zero values [9]. Furthermore, formatting issues in your input data, such as unexpected spaces or special characters in taxonomy labels, or blank cells in your taxonomy table, can cause failures in processing pipelines [10]. Always check your input tables for formatting consistency and implement an appropriate zero-handling strategy, such as Bayesian-multiplicative replacement [8] or using a pseudocount [9].

Q3: When should I use Aitchison distance over Bray-Curtis dissimilarity in my analysis?

Your choice should be guided by your biological question. Use Bray-Curtis if your research question is focused on changes in the most dominant taxa, as this metric is highly sensitive to abundant species [8]. Choose Aitchison distance if you are interested in the overall community structure and the coordinated changes among all taxa (both dominant and rare), as it is grounded in compositional theory and analyzes log-ratios [8]. For studies where the library sizes between groups vary dramatically (e.g., ~10x difference), Aitchison distance and other compositional methods are strongly recommended to avoid artifacts [9].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: High False Discovery Rate (FDR) in Differential Abundance Testing

- Symptoms: Statistical tests identify a large number of taxa as significantly different between groups, but many are likely false positives, especially when groups have very different average library sizes.

- Investigation Checklist:

- Solutions:

- For large sample sizes (>20 per group): Use ANCOM, which controls the FDR well for drawing inferences regarding taxon abundance in the ecosystem [9].

- For smaller datasets (<20 per group): Methods like DESeq2 can be more sensitive, but monitor the FDR as it can increase with more samples or uneven library sizes [9].

- Consider rarefying: While it results in a loss of sensitivity, rarefying can lower the FDR when library sizes are very uneven [9]. Always use a rarefaction depth informed by a rarefaction curve [9].

Problem: Poor Clustering in Ordination Plots (PCoA)

- Symptoms: Samples do not cluster meaningfully according to expected biological groups in a PCoA plot.

- Investigation Checklist:

- Verify the distance metric: Using a Euclidean distance metric on raw or relative abundance data is inappropriate for compositional data and will produce misleading results [8].

- Check for normalization: If not using a compositionally-aware method, ensure proper normalization has been applied to account for varying library sizes [9].

- Solutions:

Table 1: Comparison of Distance Metrics in Microbiome Analysis (G-HMP2 Dataset Example)

| Distance Metric | Mathematical Foundation | Key Feature | Variance Explained by Subject (R²) | Variance Explained by Dominant Taxa (R²) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bray-Curtis | Non-compositional (Ecological) | Emphasizes abundant taxa | 0.15 [8] | 0.24 [8] |

| Aitchison | Compositional (Log-ratios) | Balances all taxa | 0.36 [8] | 0.02 [8] |

Table 2: Performance of Differential Abundance Testing Methods Under Different Conditions

| Method | Recommended Sample Size | Handles Uneven Library Size (~10x) | Key Strength / Weakness |

|---|---|---|---|

| ANCOM | >20 per group [9] | Good control [9] | Best control of False Discovery Rate [9] |

| DESeq2 | <20 per group [9] | Higher FDR [9] | High sensitivity in small datasets; FDR can increase with more samples [9] |

| Rarefying + Nonparametric Test | Varies | Lowers FDR [9] | Controls FDR with uneven sampling; reduces sensitivity/power [9] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Conducting a Compositionally-Aware Beta-Diversity Analysis Using Aitchison Distance

This protocol details how to perform a Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) using Aitchison distance, a method grounded in compositional data theory [8].

- Data Preprocessing: Start with a raw OTU or ASV count table. Remove any samples with an extremely low number of reads.

- Zero Imputation: Aitchison distance relies on log-ratios and cannot handle zeros. Replace zeros using a Bayesian-multiplicative method (e.g.,

cmultReplfunction from thezCompositionspackage in R) [8]. - Center Log-Ratio (CLR) Transformation: Calculate the CLR for each sample. For a sample vector

xwithDtaxa, the CLR is calculated asclr(x) = [ln(x1/g(x)), ln(x2/g(x)), ..., ln(xD/g(x))], whereg(x)is the geometric mean of all taxa inx[11]. - Calculate Aitchison Distance: The Aitchison distance between two samples

xandyis the Euclidean distance of their CLR-transformed vectors:dist_A(x, y) = sqrt( sum( (clr(x) - clr(y))^2 ) )[8]. - Ordination and Visualization: Perform PCoA on the resulting Aitchison distance matrix. Visualize the PCoA results to inspect for sample clustering.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Differential Abundance with ANCOM

ANCOM (Analysis of Composition of Microbiomes) is a robust method for identifying differentially abundant taxa while controlling for false discovery [9].

- Input Data: Use the raw count data. ANCOM is designed to work with the original counts, avoiding the need for rarefaction or other normalizations that discard data [9].

- Log-Ratio Formation: For each taxon, ANCOM performs a series of statistical tests on all pairwise log-ratios between that taxon and all other taxa. This tests the null hypothesis that the log-ratio of the abundances of two taxa is not different between groups.

- Test Statistic (W): For a given taxon, the number of times it is detected as significantly different from other taxa in the pairwise log-ratio tests is counted. This count is the test statistic

W. A highWstatistic suggests the taxon is differentially abundant relative to many other taxa in the community. - Significance Determination: The empirical distribution of

Wacross all taxa is examined. A threshold (e.g., the 70th percentile of the W distribution) is often used to declare which taxa are differentially abundant, as this method provides good control of the FDR [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Methods for Microbiome CoDA

| Item / Reagent Solution | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Log-Ratio Transformations (CLR, ALR, ILR) | "Opens" the simplex, transforming compositional data into real-valued vectors for use with standard statistical and machine learning models [11]. |

| Aitchison Distance | A compositionally valid distance metric for comparing microbial communities, based on the Euclidean distance of CLR-transformed data [8]. |

| Bayesian-Multiplicative Zero Replacement | A strategy for handling zeros in compositional data (e.g., cmultRepl in R) that is more robust than simple pseudocounts for preparing data for log-ratio analysis [8]. |

| ANCOM Software | A statistical method and corresponding software implementation for differential abundance testing that provides good control of the false discovery rate [9]. |

| Simplex Visualization Tools | Software and scripts for creating ternary (3D) and higher-order simplex (4D) plots to visualize compositional data without information loss [12]. |

Workflow and Relationship Visualizations

Microbiome CoDA Analysis Workflow

Why Do We Need Special Methods for Microbiome Data?

Microbiome data, derived from high-throughput sequencing, is inherently compositional. This means the data consists of vectors of non-negative values that carry only relative information, as the total number of sequences per sample is arbitrary and uninformative [1] [13]. Analyzing this data with standard statistical methods, which assume data can vary independently, leads to spurious correlations and flawed inferences [1] [13] [2]. Compositional Data Analysis (CoDA) provides a robust framework to overcome these pitfalls, built upon three key properties: scale invariance, subcompositional coherence, and permutation invariance [1] [14] [15]. The table below summarizes these foundational properties.

Table 1: Key Properties of Compositional Data Analysis (CoDA)

| Property | Definition | Practical Implication for Microbiome Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Scale Invariance | The analysis is unaffected by multiplying all components by a constant factor [1] [15]. | Normalizing data (e.g., converting to proportions) or having different library sizes does not change the relative information in the ratios between taxa [13]. |

| Subcompositional Coherence | Results remain consistent when the analysis is performed on a subset (subcomposition) of the original components [1] [14]. | Insights gained from analyzing a select group of taxa are reliable and not an artifact of having ignored other members of the community [1] [13]. |

| Permutation Invariance | The analysis is unaffected by the order of the components in the data vector. | Standard property in multivariate analysis; the ordering of taxa in your OTU table does not influence the outcome of CoDA methods. |

The core transformation in CoDA is the log-ratio, which converts the constrained compositional data into a real-space where standard statistical methods can be safely applied [14] [13]. The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for addressing compositional data challenges, from problem identification to solution.

Troubleshooting Common CoDA Challenges

The Spurious Correlation Problem

- Observed Issue: I have found a strong negative correlation between two dominant taxa in my dataset. Is this a real biological relationship?

- Underlying Cause: This is a classic symptom of ignoring compositionality. In a composition, all parts are linked because they sum to a constant (e.g., 1 or 100%). If one taxon's proportion increases, it forces the proportions of others to decrease, creating a spurious negative correlation that may not reflect the true biological state [1] [13]. This effect is exacerbated when working with subcompositions [13].

- Solution: Analyze data using log-ratios. The correlation between two log-ratios, or between a log-ratio and an external variable, is a valid measure of association free from the spurious correlation introduced by the constant sum constraint [13] [15].

The Subcomposition Incoherence Problem

- Observed Issue: When I filter out rare taxa from my dataset, the statistical relationships between the remaining abundant taxa completely change. My results are not stable.

- Underlying Cause: Standard statistical analyses applied to raw abundances or proportions are not subcompositionally coherent. The relationship between two taxa can appear to change dramatically simply because a third, unrelated taxon was removed from the analysis [1] [13].

- Solution: Use CoDA methods based on log-ratios. A log-ratio between two taxa is immune to changes in other parts of the composition. Therefore, the relationship you measure for those two taxa remains valid regardless of which other taxa are included in or excluded from the analysis, ensuring stability and coherence [14].

The Differential Abundance Fallacy

- Observed Issue: My differential abundance test shows that 10 taxa are significantly increased in the disease group. However, I am unsure if this represents a true increase or just a relative change.

- Underlying Cause: With relative data (proportions), an increase in one taxon's proportion can cause others to appear to decrease. You cannot distinguish between an absolute increase in Taxon A versus an absolute decrease in all other taxa from compositional data alone [13]. This is a fundamental limitation.

- Solution: Frame your hypotheses and conclusions in terms of ratios. Instead of stating "Taxon A is more abundant in disease," state "The ratio of Taxon A to Taxon B (or to a reference) is higher in disease" [14] [16] [17]. Methods like

ALDEx2andcoda4microbiomeare designed for this and test for differences in log-ratios, not raw abundances [16] [17].

Experimental Protocols for Robust CoDA

Protocol 1: Additive Logratio (ALR) Transformation for Dimensionality Reduction

The ALR transformation is a simple and interpretable method to convert compositional data into a set of real-valued log-ratios.

- Preprocessing: Start with a count or proportion matrix where rows are samples and columns are taxa.

- Handle Zeros: Address zero counts using a method like Bayesian-multiplicative replacement (e.g., as implemented in the

zCompositionsR package) [17]. - Reference Selection: Choose a reference taxon (

X_ref). For high-dimensional data, select a taxon that is prevalent and has low variance in its log-transformed relative abundance to maximize isometry and ease interpretation [14]. - Transformation: For each sample and for every other taxon

j, compute:ALR(j | ref) = log(X_j / X_ref)[14]. - Downstream Analysis: The resulting

(J-1)ALR values can be used in standard statistical models like linear regression, PERMANOVA, or machine learning algorithms.

Protocol 2: Identifying Microbial Signatures with coda4microbiome

The coda4microbiome R package identifies predictive microbial signatures in the form of log-ratio balances for both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies [16].

- Data Preparation: Load your OTU table and phenotype data into R.

- Model Fitting: For a cross-sectional study, the algorithm fits a penalized regression model (e.g., elastic net) on the "all-pairs log-ratio model":

g(E(Y)) = β₀ + Σ β_jk * log(X_j / X_k)[16]. - Variable Selection: The penalization drives the selection of the most informative pairwise log-ratios for predicting the outcome

Y. - Signature Interpretation: The final model is reparameterized as a log-contrast model, which can be interpreted as a balance between two groups of taxa: those with positive coefficients and those with negative coefficients [16].

- Visualization: Use the package's plotting functions to visualize the selected taxa, their coefficients, and the model's prediction accuracy.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for CoDA

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Purpose | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Log-ratio Transformation | Converts relative abundances into real-valued, analyzable data while respecting compositionality. | ALR: log(X_j / X_ref) [14]. CLR: log(X_j / g(X)) where g(X) is the geometric mean [13]. |

R Package coda4microbiome |

Identifies microbial signatures via penalized regression on all pairwise log-ratios for cross-sectional and longitudinal data [16]. | coda4microbiome::coda_glmnet() |

R Package ALDEx2 |

Uses a Bayesian framework to model compositional data and perform differential abundance analysis between groups [17] [15]. | ALDEx2::aldex() |

| Zero Handling Methods | Addresses the challenge of sparse data with many zero counts, a common issue in microbiome datasets [17]. | Bayesian-multiplicative replacement (e.g., zCompositions package). |

The relationship between the core CoDA principles and the analytical solutions that uphold them is summarized in the following diagram.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: My data is raw count data from my sequencer, not proportions. Is it still compositional?

A: Yes. Read counts are constrained by the sequencing depth (the total number of reads per sample), which is an arbitrary constant. This induces the same dependencies and spurious correlations as working with proportions. The raw counts still only provide relative information about the taxa within each sample [13] [15].

Q: Which log-ratio transformation should I use: ALR, CLR, or ILR?

A: The choice depends on your goal and the software.

- ALR (Additive Logratio): Simple to compute and interpret, as each variable is a simple log-ratio against a reference. It is excellent for high-dimensional data and prediction tasks, though it is not isometric [14].

- CLR (Centered Logratio): Symmetrical and preserves all taxa. It is useful for computing Aitchison distances and PCA. However, the resulting variables are correlated, which can complicate some regression models [13] [15].

- ILR (Isometric Logratio): Provides an orthonormal basis, which is ideal for many multivariate statistics. However, the balances can be complex and difficult to interpret [14] [15].

Q: How do I handle zeros in my data before doing a log-ratio transformation?

A: Zeros are a major challenge because the logarithm of zero is undefined. Simple replacements (like adding a pseudo-count) can introduce biases. It is recommended to use more sophisticated methods like Bayesian-multiplicative replacement (e.g., the zCompositions R package), which are designed specifically for compositional data [17].

Q: I've heard that CoDA makes it hard to recover absolute abundances. Is that true?

A: Yes, this is a fundamental limitation. The process of sequencing and creating relative abundances or counts loses all information about the absolute number of microbes in the original sample. CoDA provides powerful tools for analyzing the relative structure of the community, but it cannot recover the absolute abundances without additional experimental data (e.g., from flow cytometry or qPCR) [1] [2].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What makes microbiome data "compositional," and why is this a problem? Microbiome sequencing data are compositional because the data you get are relative abundances (proportions) rather than absolute counts. This happens because the sequencing process forces each sample to sum to a constant total number of reads (a process called "closure") [18]. This simple feature has a major adverse effect: the abundance of one taxon appears to depend on the abundances of all others. This can lead to spurious correlations, where a change in one taxon creates illusory changes in others, violating the assumption of sample independence and biasing covariance estimates [18]. Traditional statistical methods applied to raw relative abundances can therefore produce flawed and misleading inferences.

2. My data has many zeros. What causes this sparsity, and how does it affect my analysis? Sparsity (an excess of zero values) in microbiome data arises from several factors:

- Biological Reality: The microbe might be genuinely absent from the sample [19].

- Technical Limitations: The microbe may be present but at an abundance too low for the sequencing depth to detect, a victim of undersampling [19]. This high sparsity is a significant challenge for statistical analysis. If not handled appropriately, these excessive zeros can introduce substantial bias, reducing the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of your analyses, including differential abundance testing [19].

3. How should I normalize my microbiome data to account for different sequencing depths? Proper normalization is critical to correct for varying sequencing depths (library sizes) across samples. The table below summarizes common methods, though note that "rarefying" is considered statistically inadmissible by some experts [18].

| Method | Brief Description | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Total Sum Scaling | Converts counts to relative abundances (proportions). | Does not correct for compositionality; susceptible to spurious results [18]. |

| Rarefying | Randomly subsamples reads to a common depth. | Discards data; considered "inadmissible" for some statistical tests [18]. |

| CSS (Cumulative Sum Scaling) | Normalizes using a percentile of the cumulative distribution of counts. | More robust to outliers than total sum scaling [19]. |

| GMPR | Geometric mean of pairwise ratios. | Designed specifically for zero-inflated microbiome data [19]. |

| Log-Ratio Transformation | Uses ratios of abundances within a sample (e.g., Aitchison geometry). | Directly addresses the compositional nature of the data [18]. |

4. Which statistical methods are best for identifying differentially abundant taxa? Because microbiome data are compositional and sparse, standard tests like t-tests or simple linear models are often inappropriate. Methods that explicitly account for these properties are recommended. The following table compares several approaches.

| Method | Framework | Key Feature for Microbiome Data |

|---|---|---|

| ALDEx2 | Bayesian Model / Log-Ratio | Models the compositional data within a Dirichlet distribution and uses a log-ratio approach [18]. |

| DESeq2 / edgeR | Negative Binomial Model | Designed for count-based RNA-Seq data; can be applied to microbiome data but may be sensitive to the high sparsity [19]. |

| ANCOM-BC | Linear Model / Log-Ratio | Accounts for compositionality by correcting the bias in log abundances using a linear regression framework [19]. |

| Zero-Inflated Models (e.g., ZINB) | Mixed Distribution | Explicitly models the data as coming from two processes: one generating zeros and one generating counts [19]. |

5. Can I use Machine Learning with my microbiome data, and what are the pitfalls? Yes, machine learning (ML) can be applied to microbiome data for tasks like classification or prediction. However, the compositional and sparse nature of these datasets poses a significant challenge [20]. If these properties are not considered, they can severely impact the predictive accuracy and generalizability of your ML model. Noise from low sample sizes and technical heterogeneity can further degrade performance. It is essential to use ML methods and pre-processing steps designed for or robust to these data characteristics [20].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High False Discovery Rate in Differential Abundance Analysis

Problem: Your analysis identifies many differentially abundant taxa, but you suspect many are false positives due to compositional effects and sparsity.

Solution:

- Shift to a Compositional Framework: Abandon analyses based on raw relative abundances. Instead, use methods built on log-ratio transformations (e.g., centered log-ratio, alr, or ilr) [18]. These transformations map the data from the simplex to real Euclidean space, allowing for the use of standard statistical tools.

- Apply Robust Normalization: Use a normalization method like GMPR or CSS that is more robust to the high sparsity and compositionality of the data [19].

- Choose a Suitable Model: Employ a differential abundance tool designed for these challenges, such as ALDEx2 or ANCOM-BC, which incorporate principles of compositional data analysis [18] [19].

- Validate with Care: Be cautious when interpreting p-values from models that do not account for compositionality. Consider using a tool that provides effect sizes and confidence intervals on log-ratios.

Issue 2: Managing Technical Bias and Contamination

Problem: Your data is confounded by biases from DNA extraction, PCR amplification, and contamination, making results unreliable and irreproducible.

Solution:

- Incorporate Mock Communities: Include standardized mock communities (with known compositions) in your sequencing runs. These serve as positive controls to quantify protocol-dependent biases [21].

- Use Negative Controls: Process blank (no-template) controls through your entire workflow to identify contaminants originating from reagents or the lab environment [21].

- Computational Correction: Leverage data from your mock communities to correct for observed biases. Pioneering approaches like metacal can assess and transfer bias, and newer research suggests bias can be linked to bacterial cell morphology for more general correction [21].

- Standardize Protocols: Within a study, use a single, consistent DNA extraction and library preparation protocol to minimize batch effects. The DNA extraction protocol is a major source of bias, with significant differences observed between kits and lysis conditions [21].

Diagram: Workflow for Identifying and Correcting Technical Bias.

Issue 3: Low Statistical Power Due to Data Sparsity

Problem: The high number of zeros in your dataset is reducing the power of your statistical tests, making it difficult to detect true biological signals.

Solution:

- Aggregate Data: Before analysis, consider aggregating counts at a higher taxonomic level (e.g., genus instead of species). This reduces the number of features and consequently the sparsity.

- Use Zero-Inflated Models: Implement statistical models that are specifically designed for zero-inflated data, such as zero-inflated negative binomial (ZINB) models. These models treat the zeros as coming from two sources: "true" absences and "false" absences due to undersampling [19].

- Apply Bayesian or Regularization Methods: Use methods that incorporate shrinkage or regularization (e.g., via Bayesian priors or penalized models). These techniques borrow information across features to produce more stable estimates, which is particularly helpful when data is sparse [19].

- Prune Low-Abundance Features: As a preprocessing step, filter out taxa that are present in only a very small percentage of your samples (e.g., less than 5-10%). This removes features that carry little reliable information.

Diagram: Strategies to Overcome Data Sparsity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Microbiome Research |

|---|---|

| Mock Community Standards (e.g., ZymoBIOMICS) | Defined mixtures of microbial cells or DNA with known composition. Served as positive controls to quantify and correct for technical biases across the entire workflow, from DNA extraction to sequencing [21]. |

| DNA Extraction Kits (e.g., QIAamp UCP, ZymoBIOMICS Microprep) | Kits for isolating bacterial genomic DNA from samples. Different kits, lysis conditions, and buffers have taxon-specific lysis efficiencies, making them a major source of extraction bias that must be controlled [21]. |

| Negative Control Buffers (e.g., Buffer AVE) | Sterile buffers processed alongside samples. Serves as a negative control to identify background contamination originating from reagents or the laboratory environment [21]. |

| Standardized Swabs | For consistent sample collection, particularly from surfaces like skin. Used with mock communities to test feasibility and taxon recovery of extraction protocols in specific sample contexts [21]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Spurious Correlation in Microbiome Data

- Question: Why do my microbiome datasets show unexpected or uninterpretable correlation structures between microbial features?

- Answer: High-Throughput Sequencing (HTS) data, including 16S rRNA gene amplicon and metagenomic data, are compositional [22]. This means the data convey relative abundance information, not absolute counts, because the total number of sequences obtained per sample is arbitrary and constrained by the sequencing instrument's capacity [22]. Analyzing compositional data with standard correlation methods induces a negative bias and can produce spurious correlations, a problem identified by Pearson in 1897 [22]. This is because an increase in the relative abundance of one feature necessitates an apparent decrease in others.

- Solution: Apply Compositional Data Analysis (CoDa) methods that use log-ratio transformations. These transformations account for the constant-sum constraint. Avoid using raw relative abundances or normalized counts for correlation analysis.

Problem: Low Library Yield in Sequencing Preparation

- Question: My final NGS library concentration is unexpectedly low. What are the common causes and how can I fix them?

- Answer: Low library yield can stem from issues at multiple preparation stages [23]. The root cause must be systematically diagnosed.

- Solution: Follow this diagnostic table to identify and correct the issue.

| Category of Issue | Common Root Causes | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Input / Quality | Degraded DNA/RNA; sample contaminants (phenol, salts); inaccurate quantification [23]. | Re-purify input sample; use fluorometric quantification (e.g., Qubit) instead of only absorbance; check purity ratios (260/280 ~1.8) [23]. |

| Fragmentation & Ligation | Over- or under-shearing; inefficient ligation; suboptimal adapter-to-insert ratio [23]. | Optimize fragmentation parameters; titrate adapter:insert molar ratios; ensure fresh ligase and optimal reaction conditions [23]. |

| Amplification (PCR) | Too many PCR cycles; enzyme inhibitors; primer exhaustion [23]. | Reduce the number of PCR cycles; use master mixes to reduce pipetting errors; ensure clean input sample free of inhibitors [23]. |

| Purification & Cleanup | Incorrect bead-to-sample ratio; over-drying beads; inefficient washing [23]. | Precisely follow cleanup protocol instructions for bead ratios and washing; avoid over-drying magnetic beads during cleanup steps [23]. |

Problem: Inaccurate Differential Abundance Identification

- Question: My differential abundance analysis yields a high number of false positives, especially with sparse data (many zeros). What went wrong?

- Answer: Many standard statistical tools for differential abundance assume data are absolute counts and do not account for compositionality [22]. This makes them sensitive to data sparsity and leads to unacceptably high false positive rates [22]. The relative nature of the data means a change in one feature's abundance can falsely appear to change others.

- Solution: Employ differential abundance tools specifically designed for compositional data. These methods are based on log-ratio analysis of the component structure, which provides a valid basis for inference [22].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Question: What does it mean that microbiome data are compositional?

- Answer: It means that the data from a sequencing instrument represent relative proportions, not absolute counts [22]. The total number of sequences per sample is fixed by the instrument's capacity, so the data for each sample sum to a constant (or an arbitrary total). The information is contained in the ratios between the different microbial features, not in their individual counts [22].

Question: Can't I just normalize my count data to fix compositionality?

- Answer: Common count normalization methods (e.g., TMM, Median) from RNA-seq are less suitable for highly sparse and asymmetrical microbiome datasets [22]. More critically, these methods do not fully address the fundamental issue that the data are relative, and investigators may misinterpret the normalized outputs as absolute abundances [22]. True compositional data analysis requires a paradigm shift to log-ratios.

Question: Are common distance metrics like Bray-Curtis and UniFrac invalid for compositional data?

- Answer: While useful, these distances do not fully account for compositionality. They can be strongly confounded by total read depth and primarily discriminate samples based on the most abundant features, potentially missing important variation in low-abundance taxa [22]. It is recommended to use them with caution and to explore compositional alternatives when possible, such as distances derived from log-ratio transformations [22].

Question: What deliverables should I expect from a robust CoDA-based microbiome analysis?

- Answer: A comprehensive analysis should include data processing, CoDA-specific transformations, and rigorous interpretation [24]. Key deliverables are:

- Raw data processing (quality control, denoising, taxonomic profiling).

- Alpha and beta diversity analysis using appropriate metrics.

- Exploratory data analysis with ordination plots (e.g., based on log-ratio components).

- Omnibus and per-feature statistics (e.g., using tools like

MaAsLin 2or other CoDA-aware methods) [24]. - Results interpretation and discussion within the compositional framework [24].

- Answer: A comprehensive analysis should include data processing, CoDA-specific transformations, and rigorous interpretation [24]. Key deliverables are:

Experimental Workflow & Signaling Pathways

Microbiome Data Analysis: Problematic vs. CoDA Workflow

Troubleshooting NGS Library Preparation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application | Considerations for CoDA |

|---|---|---|

| Log-Ratio Transformations | Mathematical foundation for CoDA. Transforms relative abundances from a simplex to real space for valid statistical analysis [22]. | Includes Centerd Log-Ratio (CLR) and Isometric Log-Ratio (ILR). Choice depends on the specific hypothesis and data structure. |

| Robust DNA Extraction Kit | Isolates microbial DNA from complex samples. The first step in generating HTS data. | Protocol must be consistent across samples. Does not recover absolute abundances, reinforcing the need for CoDA. |

| Fluorometric Quantification Assay | Accurately measures concentration of nucleic acids (e.g., dsDNA) using fluorescence. | Essential for verifying input material before library prep. Prevents quantification errors that lead to low yield [23]. More accurate than UV absorbance for library prep. |

| High-Fidelity Polymerase | Amplifies DNA fragments during library PCR with minimal bias and errors. | Reduces amplification artifacts and bias, which can distort the underlying composition [23]. |

| Size Selection Beads | Magnetic beads used to purify and select for DNA fragments of a desired size range. | Critical for removing adapter dimers and other artifacts. Incorrect bead ratios are a major source of library prep failure [23]. |

| CoDA-Capable Software/Packages | Statistical software (e.g., R, Python) with packages designed for compositional data analysis. | Necessary to implement log-ratio transforms and CoDA-aware differential abundance and ordination methods [22]. |

CoDA Methodologies in Practice: From Log-Ratios to Bayesian Models

Microbiome data, derived from high-throughput sequencing technologies, is inherently compositional. This means that the data represents parts of a whole, where each sample is constrained to a constant sum (e.g., the total sequencing depth) [16] [14]. Analyzing such data with standard statistical methods, which assume independence between features, can lead to spurious correlations and misleading results [25] [11]. Compositional Data Analysis (CoDA) provides a robust framework to address these challenges, with log-ratio transformations at its core [16].

This guide addresses common experimental challenges and provides troubleshooting support for implementing key log-ratio transformations—Additive (ALR), Centered (CLR), and Isometric (ILR)—in your microbiome research pipeline.

Core Concepts FAQ

What is the fundamental principle behind log-ratio transformations? Log-ratio transformations "open" the simplex, the constrained space where compositional data resides, and map the data to real Euclidean space. This allows for the valid application of standard statistical and machine learning techniques by focusing on relative information (ratios between components) rather than absolute abundances [11] [14].

Why can't I use raw relative abundances or count data directly? Using raw relative abundances or counts ignores the constant-sum constraint. This means that an observed increase in one taxon will artificially appear to cause a decrease in others, creating illusory correlations [25] [16] [11]. Furthermore, sequencing depth variation between samples is a technical artifact that does not reflect biological truth and must be accounted for [25].

How do I choose between ALR, CLR, and ILR? The choice depends on your research goal, the nature of your dataset, and the importance of interpretability versus mathematical completeness. See the section "Choosing the Appropriate Transformation: A Decision Guide" below.

Transformation Methodologies & Performance

Technical Specifications of Core Transformations

Table 1: Technical Specifications of ALR, CLR, and ILR Transformations

| Transformation | Formula | Dimensionality Output | Key Property | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Additive Log Ratio (ALR) | ALR(j) = log(X_j / X_ref) |

J-1 features (J is original number of features) [14] | Non-isometric; simple interpretation [14] | When a natural reference taxon is available and interpretability is key [25] [14] |

| Centered Log Ratio (CLR) | CLR(j) = log(X_j / g(X)) where g(X) is the geometric mean of all components [26] |

J features (same as input) [26] | Isometric; symmetric treatment of all parts [26] | Standard PCA; generating symmetric, whole-community profiles [26] [27] |

| Isometric Log Ratio (ILR) | Complex, based on sequential binary partitions of a phylogenetic tree or other hierarchy [27] | J-1 features [27] | Isometric; orthonormal coordinates [27] | Statistical methods requiring orthogonal, non-collinear predictors (e.g., linear regression) [27] |

Figure 1: A simplified workflow showing the three primary log-ratio transformation paths from raw compositional data to data ready for downstream statistical analysis.

Empirical Performance in Machine Learning Tasks

Recent large-scale benchmarking studies have yielded critical insights into the performance of these transformations in predictive modeling.

Table 2: Transformation Performance in Machine Learning Classification Tasks (e.g., Healthy vs. Diseased)

| Transformation | Reported Classification Performance (AUROC) | Key Findings and Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| ALR & CLR | Effective when zero values are less prevalent [25] | Performance can be mixed; sometimes outperformed by simpler methods in cross-study prediction [28]. |

| Presence-Absence (PA) | Comparable to, and sometimes better than, abundance-based transformations [26] | Robust performance; suggests simple microbial presence can be highly predictive. |

| Proportions (TSS) | Often outperforms ALR, CLR, and ILR by a small but statistically significant margin [27] | Read depth correction without complex transformation can be a preferable strategy for ML. |

| ILR (e.g., PhILR) | Generally performs slightly worse or only as well as compositionally naïve transformations [27] | Complex transformation may not provide a predictive advantage in ML contexts. |

| Batch Correction Methods (e.g., BMC, Limma) | Consistently outperform other normalization approaches in cross-study prediction [28] | Highly effective when dealing with data from different populations or studies (heterogeneity). |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ: Handling Zeros in Compositional Data

What is the problem with zeros? Logarithms of zero are undefined, making zeros a direct technical obstacle for any log-ratio transformation [25].

What are the common types of zeros in microbiome data?

- Biological Zero: The taxon is truly absent in the sample [25].

- Sampling Zero: The taxon is present but undetected due to limited sequencing depth [25].

- Technical Zero: Absence due to errors in sample preparation or sequencing [25].

What are the standard strategies for handling zeros?

- Pre-processing: Use a pseudo-count (a small positive value, e.g., 1) added to all counts before transformation [27]. This is simple but can bias results.

- Advanced Imputation: Replace zeros with estimated values using methods designed for compositional data, which can provide more statistically sound results [29]. The choice of method depends on the nature and abundance of zeros in your dataset.

FAQ: Dealing with High-Dimensional Data

The Pairwise-Log Ratio (PLR) approach creates too many features. How can I manage this?

A full PLR model creates K(K-1)/2 features, which for high-dimensional microbiome data leads to a combinatorial explosion [11]. Solutions include:

- Sparse Regularization: Use penalized regression (e.g., LASSO, Elastic Net) on the "all-pairs log-ratio model" to automatically select the most informative log-ratios for prediction [16].

- Targeted Log-ratios: Use phylogeny to guide the creation of log-ratios. Tools like the coda4microbiome R package or PhILR construct ILR balances based on phylogenetic trees, which reduces dimensionality and incorporates biological structure [16] [27].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Basic Workflow for Log-Ratio Transformation with Microbiome Data

- Data Preprocessing: Filter out low-prevalence taxa (e.g., those present in less than 10% of samples) to reduce noise [27].

- Handle Zeros: Apply a pseudo-count or a more sophisticated imputation method to replace zero values [29].

- Normalize to Proportions: Convert raw counts to relative abundances using Total Sum Scaling (TSS) unless using a method that incorporates scale directly [25] [26].

- Apply Log-Ratio Transformation: Choose and compute ALR, CLR, or ILR on the proportional data.

- Proceed with Downstream Analysis: Use the transformed data in your chosen statistical or machine learning model.

Figure 2: A standard experimental workflow for applying log-ratio transformations to microbiome data, from raw counts to analysis.

Protocol 2: Identifying a Microbial Signature using Penalized Regression

This protocol uses the coda4microbiome R package to identify a minimal set of taxa with maximum predictive power [16] [30].

- Construct the All-Pairs Log-Ratio Model: From your proportional data

X, create a design matrixMthat contains all possible pairwise log-ratios,log(X_j / X_k)[16]. - Perform Penalized Regression: Fit a generalized linear model (e.g., logistic regression for a binary outcome) to the model

g(E(Y)) = Mβusing an elastic net penalty. This minimizes a loss functionL(β)subject toλ₁||β||₂² + λ₂||β||₁[16]. - Cross-Validation: Use cross-validation (e.g.,

cv.glmnet) to determine the optimal penalization parameterλthat minimizes prediction error [16]. - Interpret the Signature: The model selects pairs of taxa with non-zero coefficients. The final microbial signature can be expressed as a balance—a weighted log-contrast between the group of taxa that positively influence the outcome and the group that negatively influence it [16] [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Table 3: Key Software Tools for Compositional Microbiome Analysis

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| coda4microbiome | R Package | Identifies microbial signatures via penalized regression on pairwise log-ratios for cross-sectional, longitudinal, and survival studies [16] [31] [30]. | CRAN |

| ALDEx2 | R Package | Differential abundance analysis using a CLR-based Bayesian framework [16]. | Bioconductor |

| PhILR | R Package | Implements Isometric Log-Ratio (ILR) transformations using phylogenetic trees to create "balance trees" [27]. | Bioconductor |

| glmnet | R Package | Performs penalized regression (Lasso, Elastic Net) essential for variable selection in high-dimensional models [16]. | CRAN |

| curatedMetagenomicData | R Package / Data Resource | Provides curated, standardized human microbiome datasets for benchmarking and method validation [26]. | Bioconductor |

Choosing the Appropriate Transformation: A Decision Guide

Figure 3: A practical decision guide to help researchers select an appropriate transformation or normalization strategy based on their specific analytical context and goals.

FAQs: Understanding and Addressing Zeros in Microbiome Data

FAQ 1: Why are zeros a particularly challenging problem in microbiome sequencing data? Zeros in microbiome data are challenging because they are pervasive and can arise from two fundamentally different reasons: genuine biological absence of a taxon or technical absence due to insufficient sampling depth (a missing value). This ambiguity, combined with the compositional nature of the data (where abundances are relative and sum to one), makes standard statistical approaches prone to bias. Excessive zeros are especially problematic for downstream analyses that require log-transformation, as they necessitate a value to be inserted in place of zero [32] [33].

FAQ 2: What is the simplest method to handle zeros, and what are its drawbacks? The simplest method is the pseudocount approach, where a small value (like 0.5 or 1) is added to all counts before normalization and log-transformation. The primary drawback is that this method is naive and does not exploit the underlying correlation structure or distributional characteristics of the data. It has been shown to have "detrimental consequences" in certain contexts and is far from optimal for recovering true abundances [32] [33].

FAQ 3: How do advanced imputation methods improve upon simple pseudocounts? Advanced imputation methods use sophisticated models to make an educated guess about the true abundance. For example:

- Model-Based Methods: Assume an underlying true abundance matrix and use Bayesian or variational inference to estimate it (e.g.,

mbDenoise,SAVER) [32] [33]. - Correlation-Based Methods: Use information from similar samples or similar taxa to impute missing values (e.g.,

mbImpute,scImpute) [32] [33]. - Low-Rank Approximation: Methods like

ALRAuse singular value decomposition to approximate the true, underlying abundance matrix [32] [33]. These approaches aim to be more principled by accounting for data structure, leading to more accurate recovery of true microbial profiles.

FAQ 4: What is a key limitation of many existing imputation methods that newer approaches are trying to solve? Many existing methods implicitly or explicitly assume that the abundance of each taxon follows a unimodal distribution. In reality, the abundance distribution of some taxa is bimodal, for instance, in case-control studies where a microbe's abundance is different in healthy versus diseased groups. Newer methods like BMDD (BiModal Dirichlet Distribution) explicitly model this bimodality, leading to a more flexible and realistic fit for the data and superior imputation performance [32] [33].

FAQ 5: Should I impute zeros before a meta-analysis of multiple microbiome studies? There is no consensus, and imputation may introduce additional bias in a meta-analysis context. An alternative framework like Melody is designed for meta-analysis without requiring prior imputation, rarefaction, or batch effect correction. It uses study-specific summary statistics to identify generalizable microbial signatures directly, thereby avoiding potential biases introduced by imputing data from different studies separately [34].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Choosing an Appropriate Method for Zero Handling

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Downstream log-scale analysis (e.g., PCA, log-fold-change) fails or produces errors. | Presence of zeros makes log-transformation impossible. | Apply a method to handle zeros. Start with a diagnostic of your data's distribution. |

| Differential abundance analysis results are biased or unreliable. | Compositional bias introduced by improper zero handling inflates false discovery rates. | Use a method that accounts for compositionality. Consider group-wise normalization (e.g., FTSS, G-RLE) before analysis [35]. |

| Analysis results are unstable, especially with rare taxa. | Simple pseudocounts are overly influential on low-abundance, zero-inflated taxa. | Use a model-based imputation method like BMDD or mbImpute that leverages the data's correlation structure [32] [33]. |

| Need to perform a meta-analysis across heterogeneous studies. | Study-specific biases and differing zero patterns make harmonization difficult. | Avoid imputing individual studies. Use a framework like Melody that performs meta-analysis on summary statistics without imputation [34]. |

Issue 2: Diagnosing the Nature of Zeros in Your Dataset

Objective: To assess whether zeros in your dataset are likely biological or technical, informing your choice of handling method.

Protocol Steps:

- Calculate Prevalence: For each taxon, compute the proportion of samples in which it is non-zero. Taxa with very low prevalence (e.g., present in <5% of samples) are more likely to be genuine biological absences in most samples.

- Examine Abundance Distribution: Plot the distribution of non-zero abundances for taxa of interest. If a taxon shows a bimodal distribution with one mode near zero, this is evidence that

BMDD-style bimodal modeling could be appropriate [32] [33]. - Correlate with Sequencing Depth: For a given taxon, check if the presence/absence is correlated with the sample's library size. A strong correlation suggests zeros in that taxon are likely technical (due to undersampling) [36].

- Inspect in PCA/MDS Plots: Visualize your data using principal components. If samples cluster strongly by experimental group and this separation is driven by many zero values, it suggests the zeros may contain meaningful biological signal that should be preserved.

Diagram: A workflow to diagnose the nature of zeros in a microbiome dataset.

Comparative Analysis of Zero-Handling Methods

| Method Category | Examples | Key Principle | Best Used For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudocount | Add 0.5, 1 | Add a small constant to all counts to allow log-transformation. | Quick, preliminary analyses where advanced computation is not feasible. Not recommended for final, rigorous analysis [32] [33]. |

| Model-Based Imputation | BMDD [32] [33], mbDenoise [32] [33] |

Use a probabilistic model (e.g., Gamma mixture, ZINB) to estimate true underlying abundances. | Studies aiming for accurate true abundance reconstruction, especially when taxa show bimodal distributions [32] [33]. |

| Correlation-Based Imputation | mbImpute [32] [33], scImpute |

Impute zeros using information from similar samples and similar taxa via linear models. | Datasets with a clear structure where samples/taxa are expected to be correlated. |

| Low-Rank Approximation | ALRA [32] [33] |

Use singular value decomposition to obtain a low-rank approximation of the count matrix, denoising and imputing simultaneously. | Large, high-dimensional datasets where a low-rank structure is a reasonable assumption. |

| Compositional-Aware DA | Melody [34], LinDA [34], ANCOM-BC2 [34] |

Perform differential abundance analysis by directly modeling compositionality, often avoiding the need for explicit imputation. | Differential abundance analysis, particularly in meta-analyses or when wanting to avoid potential biases from imputation. |

| Method | Key Performance Finding | Context / Note |

|---|---|---|

| BMDD | "Outperforms competing methods in reconstructing true abundances" and "improves the performance of differential abundance analysis" [32] [33]. | Demonstrated via simulations and real datasets; robust even under model misspecification. |

| Melody | "Substantially outperforms existing approaches in prioritizing true signatures" in meta-analysis [34]. | Provides superior stability, reliability, and predictive performance for identifying generalizable microbial signatures. |

| Group-Wise Normalization (FTSS, G-RLE) | "Achieve higher statistical power for identifying differentially abundant taxa" and "maintain the false discovery rate in challenging scenarios" where other methods fail [35]. | Used as a normalization step before differential abundance testing, interacting with how zeros are effectively handled. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Imputing Zeros using the BMDD Framework

Objective: To accurately impute zero-inflated microbiome sequencing data using the BiModal Dirichlet Distribution model.

Background: BMDD captures the bimodal abundance distribution of taxa via a mixture of Dirichlet priors, providing a more flexible fit than unimodal assumptions [32] [33].

Materials/Reagents:

- Software: R programming environment.

- R Package:

BMDDpackage, available from GitHub (https://github.com/zhouhj1994/BMDD) and CRAN (https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=MicrobiomeStat) [32]. - Input Data: A microbiome count table (samples x taxa).

Method Steps:

- Data Preparation: Load your count data into R. Ensure data is in a matrix or data frame format with taxa as columns and samples as rows.

- Package Installation and Loading: Install and load the

BMDDpackage. - Model Fitting: Run the BMDD model on your count data. The core function uses variational inference and an EM algorithm for efficient parameter estimation.

- Output Extraction: The result object contains the posterior means of the true compositions, which are the imputed values.

- Downstream Analysis: Use the

imputed_datamatrix for your subsequent analyses, such as differential abundance testing or clustering.

Troubleshooting:

- Computational Time: For very large datasets, the algorithm may take considerable time. Ensure you have adequate computational resources.

- Convergence Warnings: Check model convergence. The variational EM algorithm in

BMDDis designed to be scalable, but parameters can be adjusted if needed [32] [33].

Protocol 2: Conducting Meta-Analysis without Imputation using Melody

Objective: To identify generalizable microbial signatures across multiple studies without performing zero imputation.

Background: Melody harmonizes and combines study-specific summary association statistics generated from raw (un-imputed) relative abundance data, effectively handling compositionality [34].

Materials/Reagents:

- Software: R programming environment.

- R Package/Pipeline:

Melodyframework. - Input Data: A list of individual microbiome count tables and corresponding covariate data from each study for the meta-analysis.

Method Steps:

- Study-Specific Summary Statistics: For each study individually, Melody fits a quasi-multinomial regression model linking the microbiome count data to the covariate of interest. This generates summary statistics (estimates of RA association coefficients and their variances) without needing imputation or rarefaction [34].

- Summary Statistics Combination: Melody combines the RA summary statistics across all studies. It frames the meta-analysis as a best subset selection problem to estimate sparse meta absolute abundance (AA) association coefficients [34].

- Hyperparameter Tuning: The framework jointly tunes hyperparameters (a sparsity parameter

sand study-specific shift parametersδ_ℓ) using the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) to find the most sparse and consistent set of AA associations across studies [34]. - Signature Identification: The final output is a set of driver microbial signatures—taxa with non-zero estimates of the meta AA association coefficients. These are the features whose consistent change in absolute abundance is believed to drive the observed association pattern [34].

Troubleshooting:

- Reference Feature Sensitivity: The signature selection in Melody is not sensitive to the choice of reference feature used in the initial quasi-multinomial regression, as reference effects are offset during the meta-analysis step [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Software

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Handling Zeros

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Relevant Context / Note |

|---|---|---|

| BMDD R Package | Probabilistic imputation of zeros using a BiModal Dirichlet Distribution model. | Available on GitHub and CRAN. Ideal when bimodal abundance distributions are suspected [32]. |

| Melody Framework | Meta-analysis of microbiome association studies without requiring zero imputation. | Discovers generalizable microbial signatures by combining RA summary statistics [34]. |

| MetagenomeSeq | Differential abundance analysis tool that can be paired with novel normalization methods. | Using it with FTSS normalization is recommended for improved power and FDR control [35]. |

| Kaiju | Taxonomic classifier for metagenomic reads. | Useful for the initial data generation step; was identified as the most accurate classifier in a benchmark, reducing misclassification noise that could interact with zero patterns [37]. |

coda4microbiome for Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Studies

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary purpose of the coda4microbiome package? A1: The

coda4microbiomeR package is designed for identifying microbial signatures—a minimal set of microbial taxa with maximum predictive power—in cross-sectional, longitudinal, and survival studies, while rigorously accounting for the compositional nature of microbiome data [16] [31] [30]. Its aim is prediction, not just differential abundance testing.Q2: Why is a compositional data analysis (CoDA) approach necessary for microbiome data? A2: Microbiome data, whether as raw counts or relative abundances, are compositional. This means they carry only relative information, and ignoring this property can lead to spurious results and false conclusions. The CoDA framework, using log-ratios, is the statistically valid approach for such data [16] [31] [30].

Q3: What types of study designs and outcomes does coda4microbiome support? A3: The package supports three main study designs:

Q4: How is the final microbial signature interpreted? A4: The signature is expressed as a balance—a weighted log-contrast function between two groups of taxa [16] [39]. The risk or outcome is associated with the relative abundance between the group of taxa with positive coefficients and the group with negative coefficients.

Q5: Where can I find tutorials and detailed documentation? A5: The project's website (https://malucalle.github.io/coda4microbiome/) hosts several tutorials. The package vignette, available through CRAN (https://cran.r-project.org/package=coda4microbiome), provides a detailed description of all functions [16] [30].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Package Installation and Dependency Issues

- Symptoms: Errors during installation like

package not found, or failures loading required packages (e.g.,glmnet,pROC). - Solutions:

Problem: Function Execution Errors with Input Data

- Symptoms: Errors such as

'x' must be a numeric matrix, or'y' should be a factor or numeric vector. - Solutions:

- Format

xas a Matrix: The abundance table (x) must be a numeric matrix or data frame where rows are samples and columns are taxa. Pre-process your data (rarefaction, filtering) before using it with coda4microbiome. - Format

yCorrectly: Forcoda_glmnet, the outcomeymust be a vector (factor for binary, numeric for continuous). Forcoda_coxnet, ensuretimeandstatusare numeric vectors [38]. - Handle Zeros: The package uses log-ratios, so ensure your data handling (e.g., pseudocount addition) is applied prior to analysis.

- Format

Problem: Model Interpretation Challenges

- Symptoms: Difficulty understanding the selected taxa and their coefficients in the microbial signature.

- Solutions:

- Use Built-in Plots: The functions (

coda_glmnet,coda_coxnet) have ashowPlots=TRUEargument by default, which generates a signature plot showing the selected taxa and their coefficients [38]. - Understand the Balance: Interpret the results as the log-ratio between the geometric means of the two groups of taxa defined by the positive and negative coefficients [16] [39].

- Use Built-in Plots: The functions (

Problem: Poor Model Performance or Long Computation Time

- Symptoms: Low cross-validated AUC (for classification) or C-index (for survival), or the model takes too long to run.

- Solutions:

- Tune Hyperparameters: The default

alphais 0.9, but you can adjust it. Uselambda = "lambda.min"instead of the default"lambda.1se"for a less complex model [38]. - Pre-filter Taxa: For datasets with a very large number of taxa, consider a pre-filtering step (e.g., prevalence or variance) to reduce the number of taxa before running the core algorithm, as the number of all pairwise log-ratios grows quadratically.

- Check Data Quality: Ensure the outcome is not perfectly balanced and that there is a true biological signal to be captured.

- Tune Hyperparameters: The default

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Key R Packages and Their Roles in the coda4microbiome Workflow

| Package Name | Category | Primary Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| glmnet | Core Algorithm | Performs the elastic-net penalized regression for variable selection and model fitting [16] [38]. |

| pROC | Model Validation | Calculates the Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC) to assess prediction accuracy for binary outcomes [38]. |

| ggplot2 | Visualization | Generates the publication-quality plots for results, including signature and prediction plots [40] [38]. |

| survival | Survival Analysis | Provides the underlying routines for fitting the Cox proportional hazards model in coda_coxnet [38] [39]. |

| corrplot | Data Exploration | Useful for visualizing correlations, which can complement the coda4microbiome analysis [40]. |

Experimental Protocol: Cross-Sectional Analysis with coda_glmnet

This protocol outlines the steps to identify a microbial signature from a cross-sectional case-control study.

1. Data Preparation:

- Abundance Table (

x): Format your data as a matrix or data frame. Rows are individual samples, and columns are microbial taxa (e.g., genera). Apply any necessary pre-processing (e.g., adding a small pseudocount to handle zeros). - Outcome Vector (

y): For a binary outcome (e.g., Case vs Control), formatyas a factor.

2. Model Fitting:

- Run the

coda_glmnetfunction with your data. It's good practice to set a random seed for reproducibility. - Example Code:

3. Interpretation of Results:

- The function output is a list. Use

results$taxa.nameto see the selected taxa andresults$log-contrast coefficients` to see their weights. - The model will automatically generate two plots:

- Signature Plot: Visualizes the selected taxa and their coefficients.

- Prediction Plot: Shows the model's predicted values, grouped by the outcome.

4. Validation:

- The output provides apparent AUC and cross-validated AUC (mean and standard deviation) to help assess the model's predictive performance [38].

Troubleshooting Workflow Diagram

Microbiome data are inherently compositional. This means that the data represent relative abundances, where each taxon's abundance is a part of a whole (the total sample), and all parts sum to a constant [41] [36]. This fixed-sum constraint means that the abundances are not independent; an increase in one taxon must be accompanied by a decrease in one or more others [41]. Analyzing such data with standard statistical methods, which assume data can exist in unconstrained Euclidean space, is problematic and can lead to spurious correlations and misleading results [42] [43]. Compositional Data Analysis (CoDA) provides a robust statistical framework specifically designed for such data, using log-ratio transformations to properly handle the relative nature of the information [42] [44].

The analysis of microbiome data presents several unique challenges. Beyond compositionality, the data are often high-dimensional (with far more taxa than samples), sparse (containing many zero counts), and overdispersed [36]. These characteristics complicate the identification of taxa that are genuinely associated with health outcomes or disease states. The Bayesian Compositional Generalized Linear Mixed Model (BCGLMM) is a recently developed advanced method that addresses these challenges directly, offering a powerful approach for predictive modeling using microbiome data [41] [45] [46].

Understanding the BCGLMM Framework

Core Model Specification

The BCGLMM is built upon a standard generalized linear mixed model but is specifically adapted for compositional covariates [41] [46]. The model consists of three key components: a linear predictor, a link function, and a data distribution.

The linear predictor ((\eta)) incorporates the compositional covariates and a random effect term [41]: [\etai = \beta0 + \mathbf{xi \beta} + ui] where (\mathbf{u} \sim MVN_n(\mathbf{0}, \mathbf{K}\nu))

To handle the compositional nature of the microbiome data, a log-transformation is applied to the relative abundances, and a soft sum-to-zero constraint is imposed on the coefficients to satisfy the constant-sum constraint [41] [46]: [\boldsymbol{\eta} = \beta0 + \mathbf{Z \beta^*} + \mathbf{u}, \quad \sum{j=1}^{m} \betaj^* = 0] Here, (\mathbf{Z} = { \log(x{ij}) }) is the (n \times m) matrix of log-transformed relative abundances. The sum-to-zero constraint is realized through "soft-centers" by assuming (\sum{j=1}^{m} \betaj^* \sim N(0, 0.001 \times m)) [41].

The Innovation: Capturing Major and Minor Effects