Navigating the Multiple Comparisons Problem in Microbiome Analysis: A Practical Guide for Robust Statistical Inference

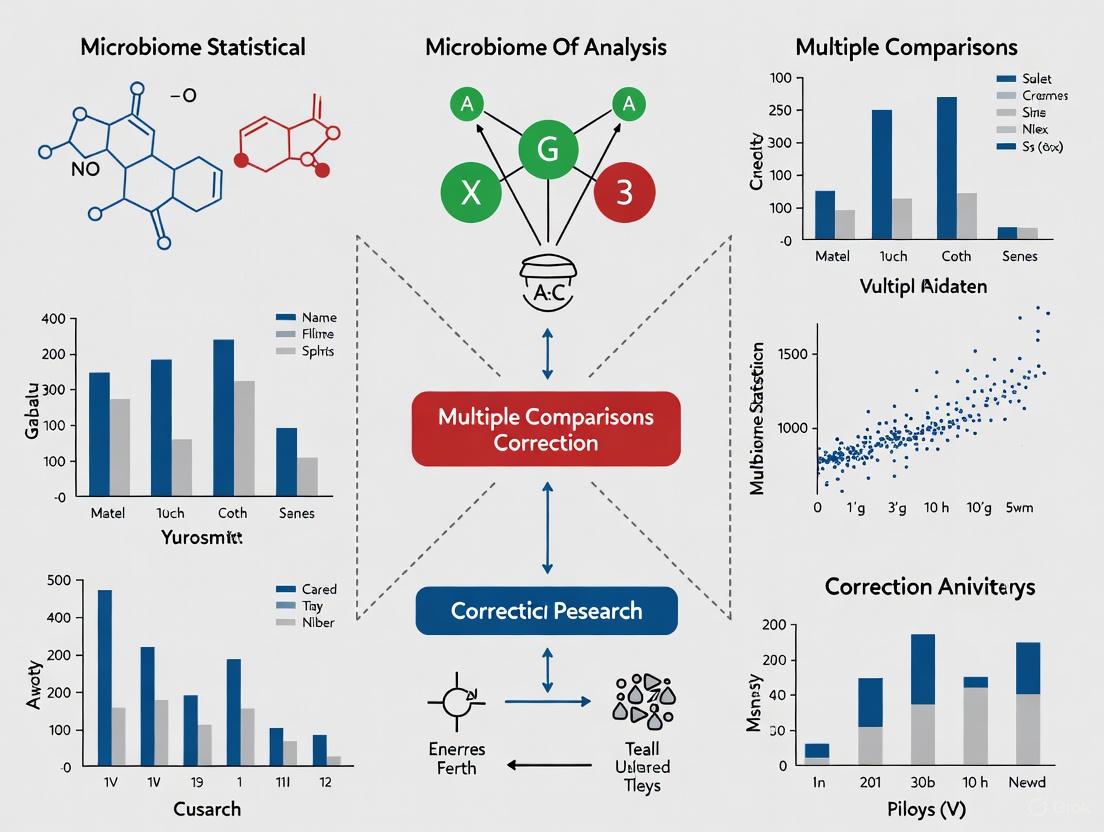

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to address the critical challenge of multiple comparisons correction in microbiome statistical analysis.

Navigating the Multiple Comparisons Problem in Microbiome Analysis: A Practical Guide for Robust Statistical Inference

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to address the critical challenge of multiple comparisons correction in microbiome statistical analysis. Covering the full analytical workflow, we explore the foundational concepts of false discovery rates in high-dimensional data, detail advanced methodologies like ANCOM-BC2 and mi-Mic that account for compositional and phylogenetic structure, and present optimization strategies for handling batch effects, zero-inflation, and other common pitfalls. Through comparative evaluation of contemporary methods and validation approaches, we offer practical guidance for implementing statistically robust differential abundance analysis that controls false discoveries while maintaining power, ultimately enabling more reliable biological insights and translational applications.

The Multiple Testing Challenge in Microbiome Science: Understanding the Why and How of False Discovery Control

High-throughput sequencing technologies, such as 16S rRNA gene sequencing and metagenomic shotgun sequencing, have revolutionized microbiome research by enabling comprehensive profiling of microbial communities. These methods generate data characterized by exceptionally high dimensionality, where the number of microbial features (taxa or genes) vastly exceeds the number of samples. This high-dimensional structure necessitates performing thousands of simultaneous statistical tests to identify differentially abundant features, creating a substantial multiple comparisons problem that demands rigorous correction to avoid a flood of false discoveries.

The fundamental challenge lies in distinguishing true biological signals from background noise when testing numerous hypotheses concurrently. Without appropriate statistical correction, researchers risk identifying apparently significant microbial associations that occur purely by chance, compromising the validity and reproducibility of their findings. This application note examines the nature of high-dimensional microbiome data, the consequences of uncorrected multiple testing, and provides structured solutions for maintaining statistical integrity in microbiome research.

The High-Dimensional Challenge in Microbiome Data

Microbiome data possess several intrinsic characteristics that complicate statistical analysis and necessitate specialized multiple testing approaches:

Data Characteristics Complicating Analysis

- Zero Inflation: Microbiome datasets typically contain an excess of zero values (up to 90% of all counts), arising from both biological absence and technical limitations in detecting low-abundance taxa [1].

- Compositionality: Sequencing data provide only relative abundance information, where each feature's abundance depends on the abundances of all other features in the sample [2].

- Overdispersion: Microbial counts exhibit greater variability than would be expected under standard statistical distributions, requiring specialized modeling approaches [3] [1].

- High Dimensionality: Typical microbiome studies measure hundreds to thousands of microbial features across far fewer samples, creating a "p ≫ n" problem (where number of features p greatly exceeds number of samples n) [1].

The Multiple Testing Problem Magnified

In a typical differential abundance analysis with 1,000 microbial features, using a standard significance threshold of p < 0.05, we would expect approximately 50 features to be identified as significant purely by chance alone. This fundamental multiple testing problem is exacerbated by the intercorrelated nature of microbial data and its unique statistical properties.

Table 1: Consequences of Uncorrected Multiple Testing in Microbiome Studies

| Testing Scenario | Significance Threshold | Expected False Positives (1000 features) | Impact on Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uncorrected | p < 0.05 | 50 | High likelihood of false microbial associations |

| Benjamini-Hochberg FDR | FDR < 0.05 | 5 | Improved specificity but potential loss of power |

| Bonferroni | p < 0.00005 | 0.05 | Stringent control but substantial power loss |

Performance of Differential Abundance Methods

Different statistical approaches for differential abundance analysis exhibit varying performance characteristics in handling high-dimensional microbiome data, particularly in their ability to control false discoveries while maintaining power to detect true differences.

Method Variability and Consistency Concerns

A comprehensive evaluation of 14 differential abundance testing methods across 38 microbiome datasets revealed substantial inconsistencies in results. Different methods identified drastically different numbers and sets of significant taxa, with the percentage of significant features ranging from 0.8% to 40.5% depending on the method used [2]. This method-dependent variability underscores the challenge of obtaining reliable conclusions without appropriate statistical correction.

Table 2: Performance Characteristics of Common Differential Abundance Methods

| Method | Statistical Foundation | False Discovery Control | Handling of Microbiome Data Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALDEx2 | Compositional, CLR transformation | Conservative, lower false positives | Addresses compositionality, robust to sparse data |

| ANCOM-II | Compositional, log-ratio based | Strong false discovery control | Specifically designed for compositional data |

| DESeq2 | Negative binomial model | Variable performance with defaults | Handles overdispersion but sensitive to compositionality |

| edgeR | Negative binomial model | Can produce high false positives | Handles overdispersion, less suited for compositionality |

| limma-voom | Linear models with precision weights | Can produce high false positives | Moderate handling of microbiome characteristics |

| LEfSe | Kruskal-Wallis with LDA | Moderate false discovery control | Incorporates biological consistency and effect size |

Benchmarking Insights

Recent benchmarking studies using realistic simulated data have demonstrated that only a subset of differential abundance methods properly controls false discoveries while maintaining adequate sensitivity. Methods including classic linear models, Wilcoxon test, limma, and fastANCOM have shown acceptable false discovery control, while many other popular approaches produce unacceptably high false positive rates [4]. The performance issues are further exacerbated when analyzing confounded data, highlighting the critical importance of both appropriate method selection and multiple testing correction.

Statistical Frameworks for Multiple Testing Correction

False Discovery Rate Control Methods

The Benjamini-Hochberg procedure for controlling the False Discovery Rate (FDR) has become the standard approach for multiple testing correction in microbiome studies. Unlike family-wise error rate methods like Bonferroni that control the probability of any false discovery, FDR methods control the expected proportion of false discoveries among all significant tests, providing a more balanced approach for high-dimensional data.

P-value Combination Approaches

Given the inconsistency in results across different differential abundance methods, researchers have explored p-value combination techniques to integrate evidence across multiple statistical approaches. These meta-analysis methods provide a more robust foundation for identifying truly important microbial taxa.

Table 3: P-value Combination Methods for Microbiome Data

| Method | Underlying Principle | Handling of Dependencies | Performance in Microbiome Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cauchy Combination Test | Heavy-tailed distribution | Accommodates correlated p-values | Best overall performance in simulations |

| Fisher's Method | Product of p-values | Assumes independence | Can be anti-conservative with dependencies |

| Stouffer's Method | Inverse normal transformation | Assumes independence | Moderate performance |

| Minimum P-value Method | Most significant result | Accounts for dependencies | Conservative approach |

| Simes Method | Ordered p-values | Adaptive to correlation structure | Moderate performance |

Simulation studies evaluating these combination methods have demonstrated that the Cauchy combination test provides the best combined p-value while properly controlling type I error rates and producing high rank similarity with true differentially abundant features [5].

Experimental Protocols for Robust Analysis

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Differential Abundance Analysis with Multiple Testing Correction

Purpose: To identify differentially abundant microbial features while controlling false discoveries.

Materials and Reagents:

- R statistical environment (v4.3.0 or higher)

- Bioconductor packages: DESeq2, metagenomeSeq, limma

- CRAN packages: ALDEx2, corncob

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing: Filter low-abundance taxa using a prevalence threshold of 10% (present in at least 10% of samples) [2].

- Multiple Method Application:

- Apply at least three different differential abundance methods (e.g., ALDEx2, DESeq2, limma-voom)

- Use default parameters for each method as recommended by developers

- Extract raw p-values and effect sizes for each feature

- P-value Combination:

- Apply Cauchy combination test to integrate p-values across methods [5]

- Alternatively, use Fisher's method for independent confirmation

- False Discovery Rate Control:

- Apply Benjamini-Hochberg procedure to combined p-values

- Use FDR threshold of 0.05 for significance declaration

- Biological Validation:

- Examine effect sizes for statistically significant features

- Assess consistency with prior biological knowledge

- Perform sensitivity analysis with different filtering thresholds

Troubleshooting:

- If too few features are significant, consider using less stringent filtering thresholds

- If consistency across methods is low, investigate data quality and potential confounding

- Verify that library size differences have been appropriately addressed

Protocol 2: Power-Optimized Analysis for Biomarker Discovery

Purpose: To maximize power for detecting true microbial biomarkers while controlling false discoveries.

Materials and Reagents:

- R packages: factoextra, missMDA, microbiome

- Python packages: scikit-bio, pandas

Procedure:

- Exploratory Data Analysis:

- Perform principal coordinate analysis to identify major sources of variation

- Assess data sparsity and zero inflation patterns

- Preprocessing Optimization:

- Test multiple normalization methods (CSS, TMM, RLE, TSS)

- Compare rarefied and non-rarefied approaches

- Evaluate different prevalence filtering thresholds (0.001%-0.05%) [6]

- Staged Analysis Approach:

- Stage 1: Apply liberal threshold (FDR < 0.10) with multiple methods

- Stage 2: Validate candidate features using independent method class

- Stage 3: Apply consensus approach requiring significance across multiple methods

- Confounder Adjustment:

- Validation:

- Perform cross-validation within dataset

- Compare with external datasets when available

- Assess biological plausibility of findings

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Tools for High-Dimensional Microbiome Analysis

| Tool/Platform | Function | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| QIIME2 | Data processing pipeline | 16S rRNA analysis | End-to-end analysis, quality control, diversity metrics |

| DADA2 | Sequence variant inference | 16S rRNA denoising | High-resolution amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) |

| DESeq2 | Differential abundance analysis | RNA-Seq and microbiome data | Negative binomial models, shrinkage estimation |

| ALDEx2 | Differential abundance analysis | Compositional data | CLR transformation, handles sparse data |

| ANCOM-II | Differential abundance analysis | Compositional data | Addresses compositionality without transformation |

| metagenomeSeq | Differential abundance analysis | Sparse microbiome data | Zero-inflated Gaussian models, CSS normalization |

| LEfSe | Biomarker discovery | Class comparison | Incorporates biological consistency and effect size |

| Cauchy Combination Test | P-value integration | Meta-analysis across methods | Robust to dependencies between tests |

| ComBat | Batch effect correction | Multi-study integration | Empirical Bayes framework for batch adjustment |

| ConQuR | Batch effect correction | Cross-study analysis | Conditional quantile regression for microbiome data [7] |

| Dasolampanel | Dasolampanel | Dasolampanel is a selective non-competitive AMPA receptor antagonist for neurological research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). | Bench Chemicals |

| Ebopiprant | Ebopiprant (OBE022) | Ebopiprant is a novel, orally active PGF2α receptor antagonist for preterm labor research. This product is For Research Use Only, not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

The high-dimensional nature of microbiome data presents both opportunities and challenges for statistical analysis. The imperative for multiple testing correction stems from the fundamental mismatch between the number of features examined and the number of samples available, creating a multiple comparisons problem that, if unaddressed, generates excessive false discoveries and compromises research reproducibility. Through the implementation of robust statistical frameworks—including false discovery rate control, p-value combination methods, and consensus approaches across multiple differential abundance methods—researchers can navigate these challenges effectively. The protocols and tools presented here provide a foundation for conducting statistically sound microbiome analyses that balance discovery power with false positive control, ultimately strengthening the biological conclusions drawn from high-dimensional microbial datasets.

In microbiome research, the analysis of high-dimensional sequencing data necessitates testing the abundance of thousands of microbial taxa across different sample groups. Traditional multiple comparison corrections, like the Bonferroni method, control the Family-Wise Error Rate (FWER) and are often overly conservative, leading to a high rate of false negatives and missed biological discoveries. This article explores modern error metrics, specifically the False Discovery Rate (FDR) and its advanced extensions, which offer a more balanced and powerful statistical framework for differential abundance analysis. We provide a structured overview of these metrics, benchmark their performance using recent comparative studies, and present detailed application protocols to guide researchers in selecting and implementing appropriate multiple testing corrections in microbiome studies.

Microbiome studies routinely involve sequencing hundreds of samples to profile complex microbial communities. A foundational goal is to identify taxa that are differentially abundant (DA) between conditions—for instance, healthy versus diseased states. This involves performing a statistical test for each of thousands of taxa, leading to a severe multiple comparisons problem. The probability of incorrectly declaring a non-differential taxon as significant (a Type I error, or false positive) increases dramatically with the number of hypotheses tested.

The traditional Bonferroni correction controls the Family-Wise Error Rate (FWER), defined as the probability of at least one false positive among all hypotheses. For m simultaneous tests, it sets the significance threshold at α/m. While this stringently controls false positives, it drastically reduces statistical power (increases false negatives), a critical drawback in exploratory microbiome studies where identifying potential biomarkers is key [8] [9].

Modern approaches have shifted towards controlling the False Discovery Rate (FDR)—the expected proportion of false discoveries among all taxa declared significant. An FDR of 5% means that, on average, 5% of the significant findings are expected to be false positives. This paradigm, introduced by Benjamini and Hochberg (BH), allows researchers to tolerate a known proportion of false positives in exchange for greater power to detect true positives, making it particularly suitable for high-dimensional, exploratory microbiome analyses [9].

Key Error Metrics and Their Applications

Understanding the Spectrum of Error Rates

- Family-Wise Error Rate (FWER): The probability of making one or more false discoveries. Methods like Bonferroni provide strong control but are overly conservative for microbiome data, often resulting in no significant findings despite real biological differences [8].

- False Discovery Rate (FDR): The expected proportion of incorrectly rejected null hypotheses (false positives) among all rejected hypotheses. If V is the number of false positives and R is the total number of significant taxa, then FDR = E[V/R]. This is less stringent than FWER and is the standard for most microbiome DA analyses [9].

- Positive FDR (pFDR): A variant of FDR defined as E[V/R | R > 0], the expected rate conditional on at least one rejection. This is often more relevant in practice where we always expect some findings [9].

- q-value: The FDR analog of the p-value. For a given taxon, its q-value is the minimum FDR at which it would be deemed significant. A q-value of 0.05 for a taxon indicates that 5% of taxa with q-values as small or smaller than this are expected to be false positives [9].

Advanced FDR Methodologies for Microbiome Data

The unique characteristics of microbiome data—sparsity, compositionality, and phylogenetic structure—have spurred the development of specialized FDR-controlling methods.

- Discrete FDR (DS-FDR): Standard BH procedure can be over-conservative with discrete test statistics common in sparse, low-sample-size microbiome data. DS-FDR is a permutation-based method that exploits the discreteness of the data to improve power, reportedly doubling the number of true positives detected compared to BH in some simulations and halving the required sample size to achieve the same power [8].

- Hierarchical and Two-Stage FDR Control: These methods leverage the taxonomic tree structure. A first stage screens for association at a higher taxonomic rank (e.g., family), and a second stage tests individual taxa (e.g., species) only within significant higher-ranked groups. Frameworks like

massMapuse procedures like Hierarchical BH (HBH) to control the FDR, increasing power by reducing the multiple testing burden based on evolutionary relationships [10]. - Multivariate FDR Control: Methods like the Multi-Response Knockoff Filter (MRKF) move beyond testing taxa individually. They use a multivariate regression model to identify microbial features associated with multiple outcomes while controlling the FDR, enhancing power by modeling correlations among outcomes [11].

- Integrative FDR Strategies for Multi-Omics: As studies integrate microbiome data with metabolomics, new strategies are required. Benchmarking studies suggest that the choice of global association tests, data summarization methods, and feature selection algorithms must be tailored to the specific research question and data structure to effectively control false discoveries across omic layers [12].

Comparative Performance of FDR-Controlling Methods

Large-scale benchmarking studies have evaluated the performance of various differential abundance methods, many of which implement different FDR-control strategies. A seminal study compared 14 DA tools across 38 real 16S rRNA datasets [2] [13].

Table 1: Characteristics of Selected Differential Abundance Methods and Their FDR Control

| Method | Underlying Principle | FDR Control Procedure | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| LEfSe | Kruskal-Wallis, LDA | Not originally designed for FDR control [13] | Can produce high false positive rates if not used with care [2]. |

| DESeq2 | Negative Binomial Model | Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) [13] | May be conservative for microbiome data; assumes independent tests [14]. |

| ALDEx2 | Compositional, CLR Transformation | Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) [13] | Shows consistent results across studies; good FDR control but lower power [2]. |

| ANCOM-II | Compositional, Log-Ratios | Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) [13] | Robust and consistent; considered conservative but reliable [2]. |

| mi-Mic | Phylogenetic Cladogram | Two-stage correction on cladogram paths and leaves | Aims for a higher true-to-false positive ratio by incorporating taxonomy [14]. |

| DS-FDR | Permutation-based | Discrete FDR estimation | Higher power for sparse, small-sample-size data [8]. |

Table 2: Practical Implications of Method Choice from Benchmarking Studies

| Performance Aspect | Finding | Implication for Researchers |

|---|---|---|

| Result Concordance | Different tools identified drastically different numbers and sets of significant taxa [2] [13]. | Biological interpretations are highly method-dependent. |

| Consistency | ALDEx2 and ANCOM-II produced the most consistent results across diverse datasets [2]. | Recommended for robust, conservative discovery. |

| False Positive Rate | Some methods, like edgeR and metagenomeSeq, can exhibit unacceptably high false positive rates [2] [13]. | Method choice should be validated with simulations if possible. |

| Power vs. Conservatism | DS-FDR and two-stage methods (e.g., massMap) demonstrate higher power to detect true positives under controlled FDR in simulations [8] [10]. |

Beneficial for studies with limited sample sizes or expected subtle effects. |

Experimental Protocols for FDR-Controlled Analysis

Protocol 1: Implementing Standard and Discrete FDR Control

Application: Identifying differentially abundant taxa between two groups (e.g., Case vs. Control) from a 16S rRNA sequencing count table.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Computing Environment: R Statistical Software (v4.0 or higher).

- Data Input: A taxa (rows) x samples (columns) count matrix and a metadata file with group labels.

- Key R Packages:

stats(for BH procedure),dsfdr(for DS-FDR implementation [8]).

Workflow:

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing: Filter the dataset to remove taxa with very low prevalence or abundance (e.g., present in less than 10% of samples). This independent filtering step can increase power without inflating the FDR [2].

- Generate Test Statistics and Raw P-values: For each taxon, compute a test statistic comparing the two groups. Common choices include the Wilcoxon rank-sum test (non-parametric) or a negative binomial model test (e.g., from

DESeq2). This yields a vector of raw, unadjusted p-values. - Apply FDR Correction:

- Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) Procedure:

- Order the m p-values from smallest to largest: ( P{(1)} \leq P{(2)} \leq ... \leq P{(m)} ).

- Find the largest k such that ( P{(k)} \leq \frac{k}{m} \alpha ), where α is the desired FDR level (e.g., 0.05).

- Declare the taxa corresponding to the first k p-values as significant.

- Discrete FDR (DS-FDR):

- Use a dedicated function/tool like

dsfdr. - The method permutes the group labels many times (e.g., 1,000) to generate a null distribution of test statistics, accounting for their discreteness.

- It then estimates the FDR for various significance thresholds and returns the list of significant taxa that meet the target FDR.

- Use a dedicated function/tool like

- Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) Procedure:

Protocol 2: A Two-Stage, Phylogeny-Aware FDR Workflow

Application: Leveraging taxonomic hierarchy to improve the power of species-level differential abundance analysis.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Computing Environment: R Statistical Software.

- Data Input: A taxa x count matrix with full taxonomic lineage (from Phylum to Species) and metadata.

- Key R Packages/Pipelines:

massMap[10],miMic(incorporates a similar cladogram-based approach [14]).

Workflow:

Procedure:

- Select a Screening Rank: Choose an intermediate taxonomic rank (e.g., Family or Order) for the first stage. This balances the power of group-level tests with the signal condensation needed for the second stage [10].

- Stage 1 - Group Screening: For each group (e.g., each family), test the global hypothesis that at least one taxon within the group is associated with the outcome. Use a powerful microbiome group test like OMiAT, which is robust to various association patterns. Apply an FDR correction (e.g., BH) to the p-values from these group-level tests and retain groups that are significant at, for example, a 20% FDR level.

- Stage 2 - Within-Group Taxon Testing: For all species belonging to the significant families from Stage 1, perform individual association tests (e.g., Wilcoxon, regression). This yields a list of p-values for this pre-filtered subset of species.

- Advanced FDR Control: Apply an FDR-controlling procedure that accounts for the two-stage structure to the p-values from Stage 2.

- Hierarchical BH (HBH): A simple approach is to apply the standard BH procedure only to the p-values from the second stage. This controls the FDR for the entire analysis [10].

- Selected Subset Testing (SST): More advanced methods can offer further power improvements by weighting hypotheses based on the first-stage results.

Table 3: Key Software and Analytical Resources for FDR Control

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| R Statistical Software | Programming Environment | Core platform for statistical computing and graphics. | Foundation for running all below packages and custom analyses. |

| DESeq2 / edgeR | R Package | Models count data using negative binomial distribution and applies BH correction. | Best for RNA-seq derived count data; can be applied to microbiome data but may be conservative [2] [13]. |

| ALDEx2 / ANCOM-II | R Package | Compositional data analysis (CLR/ALR transformations) with BH correction. | Recommended for robust, conservative analysis of microbiome relative abundances [2] [13]. |

| massMap Framework | R Package | Two-stage microbial association mapping with HBH/SST FDR control. | Ideal for leveraging taxonomic structure to gain power for species-level discovery [10]. |

| DS-FDR Tool | R Function | Permutation-based FDR control for discrete test statistics. | Superior for studies with small sample sizes or very sparse data [8]. |

| mi-Mic | Pipeline/R Package | Phylogeny-aware differential abundance testing using a cladogram of means. | Reduces multiple testing burden by incorporating phylogenetic relationships [14]. |

| Knockoff Filter (MRKF) | R Code | FDR-controlled variable selection in multivariate regression. | Advanced method for integrating microbiome data with multiple correlated outcomes [11]. |

The move from Bonferroni to FDR-based methods represents a critical evolution in the statistical analysis of microbiome data, enabling more powerful and meaningful discovery. However, no single method is universally superior. The choice of an FDR-control strategy must be informed by the specific data characteristics—such as sample size, sparsity, and whether phylogenetic or multi-omics data is integrated. Benchmarking studies consistently recommend using a consensus approach, where multiple well-performing methods (e.g., ALDEx2, ANCOM-II) are applied, and results overlapping across methods are considered high-confidence findings [2]. As the field progresses, methods that explicitly account for the discreteness, compositionality, and complex structure of microbiome data, such as DS-FDR and phylogeny-aware frameworks, are poised to become the new standard for robust differential abundance analysis.

High-throughput sequencing technologies allow researchers to profile hundreds to thousands of microbial taxa simultaneously from a single sample. While this provides a comprehensive view of microbial communities, it introduces a critical statistical challenge: the multiple comparisons problem. When conducting differential abundance (DA) analysis, researchers typically test each taxon individually for association with a phenotype or treatment. Performing hundreds of simultaneous statistical tests dramatically increases the probability of false discoveries. Without proper correction, the likelihood of falsely identifying taxa as significantly different (false positives) can exceed 50% in standard microbiome analyses [2]. This article examines how uncorrected multiplicity inflates false positive rates, provides protocols for implementing appropriate corrections, and offers practical solutions for maintaining statistical rigor in microbiome studies.

The fundamental issue stems from the definition of the significance threshold (α), typically set at 0.05. This represents a 5% chance of a false positive for a single test. However, when testing 1,000 taxa simultaneously, even if no taxa are truly differentially abundant, we would expect approximately 50 taxa to show p-values < 0.05 by chance alone. Microbiome data exacerbates this problem through its unique characteristics: high dimensionality (many taxa), compositionality (relative abundances sum to a constant), and complex correlation structures between microbial taxa [15] [12]. Understanding and addressing these issues is crucial for generating biologically valid conclusions in microbiome research.

Quantitative Evidence of Multiplicity Problems

Empirical Evidence from Method Comparisons

A comprehensive evaluation of 14 differential abundance methods across 38 microbiome datasets revealed striking inconsistencies in results depending on the statistical approach used. The percentage of significant amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) identified varied dramatically between methods, with means ranging from 0.8% to 40.5% across datasets when no prevalence filtering was applied [2]. This remarkable variation highlights how methodological choices, including multiplicity correction approaches, can drastically impact biological interpretations.

Some methods consistently identified more significant features than others. For instance, limma voom (TMMwsp) identified a mean of 40.5% significant ASVs across datasets, while other methods identified as few as 0.8% on average [2]. In extreme cases, certain methods flagged over 99% of ASVs as significant in specific datasets, while other methods found almost none. These discrepancies directly result from differences in how methods handle compositionality, normalization, and multiple testing correction.

Impact of Experimental and Computational Artifacts

Beyond traditional multiple testing problems, microbiome data faces additional sources of false positives. Index misassignment during sequencing, particularly prominent on Illumina NovaSeq platforms (5.68% of reads vs. 0.08% on DNBSEQ-G400), introduces false positive rare taxa that further complicate statistical analysis [16]. These technical artifacts inflate perceived diversity metrics and can lead to incorrect ecological inferences about community assembly mechanisms and keystone species.

Batch effects represent another source of spurious findings. When analyzing data across multiple studies or sequencing batches, systematic technical variations can create apparent biological signals. Without appropriate batch correction methods, these artifacts can be misinterpreted as biologically significant findings [17]. Studies have shown that proper normalization and batch effect correction are prerequisites for valid multiple testing correction in microbiome analyses.

Statistical Frameworks for Multiplicity Correction

Standard Multiple Testing Corrections

The most common approaches for addressing multiplicity include:

- Bonferroni Correction: The most conservative method, which divides the significance threshold (α) by the number of tests (m). This controls the Family-Wise Error Rate (FWER) but substantially reduces power in high-dimensional microbiome data.

- Benjamini-Hochberg Procedure: Controls the False Discovery Rate (FDR) by ranking p-values and using a step-up procedure to determine significance. This method offers better balance between false positive control and power for microbiome studies.

- Storey's q-value: An FDR-based approach that estimates the proportion of true null hypotheses from the distribution of observed p-values, offering improved power over Benjamini-Hochberg.

Table 1: Comparison of Multiple Testing Correction Methods

| Method | Error Rate Controlled | Strengths | Limitations | Suitable For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bonferroni | Family-Wise Error Rate (FWER) | Strong control of false positives | Overly conservative, low power | Small number of tests, confirmatory studies |

| Benjamini-Hochberg | False Discovery Rate (FDR) | Balance between discovery and error control | Can be anti-conservative with dependent tests | Most microbiome differential abundance studies |

| q-value | FDR with estimated null proportion | Improved power over Benjamini-Hochberg | Requires large number of tests for accurate estimation | Large-scale exploratory studies |

| Permutation-based FDR | FDR with empirical null | Accounts for correlation structure | Computationally intensive | Complex study designs with correlated features |

Compositionally Aware Methods

Standard multiple testing corrections assume tests are independent, an assumption violated in microbiome data due to compositional and ecological constraints. Newer methods specifically designed for microbiome data incorporate compositionality directly into their framework:

ANCOM-BC estimates sampling fractions and corrects for bias introduced by differences across samples using a linear regression framework with appropriate FDR control [15]. Unlike earlier approaches, it provides statistically valid tests with appropriate p-values and confidence intervals for differential abundance of each taxon.

ALDEx2 uses a Dirichlet-multinomial model to estimate the technical uncertainty in sequencing data and implements a scale model-based approach to account for uncertainty in microbial load, effectively generalizing standard normalizations [18]. This approach can drastically reduce both false positive and false negative rates compared to normalization-based methods.

Table 2: Compositionally Aware Differential Abundance Methods

| Method | Statistical Approach | Compositionality Handling | FDR Control | Recommended Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANCOM-BC | Linear regression with bias correction | Sampling fraction estimation | Yes | Most differential abundance analyses |

| ALDEx2 | Dirichlet-multinomial model with scale uncertainty | Monte Carlo sampling from Dirichlet prior | Yes | Studies with uncertain microbial load |

| MaAsLin2 | Generalized linear models with random effects | Data transformations (CLR, log) | Yes | Longitudinal studies or complex random effects |

| DESeq2/modified | Negative binomial models | Proper filtering and independent filtering | Yes | With careful attention to compositionality limitations |

Experimental Protocols for False Positive Control

Protocol 1: Standardized Differential Analysis Workflow

Purpose: To provide a robust workflow for differential abundance analysis with proper false positive control.

Materials:

- Processed microbiome count table (OTU/ASV table)

- Sample metadata with experimental groups

- R statistical environment with required packages

Procedure:

Preprocessing and Filtering

- Apply prevalence filtering to remove taxa present in fewer than 10% of samples [2]

- Do not use abundance-based filtering unless independent of test statistic

- Consider rarefaction only if necessary for specific methods

Method Selection and Application

- Select appropriate compositionally aware methods (ANCOM-BC, ALDEx2, or MaAsLin2)

- For ANCOM-BC:

- For ALDEx2 with scale models:

Multiple Testing Correction

- Apply Benjamini-Hochberg FDR correction to all tested taxa

- Use a conservative FDR threshold (e.g., 0.05) for discovery

- For confirmatory studies, consider using FWER control

Result Validation

- Compare results across multiple differential abundance methods

- Check consistency of effect directions and significance

- Validate findings with external data or experimental validation when possible

Figure 1: Differential Abundance Analysis Workflow with False Positive Control. This workflow ensures proper handling of multiple testing at critical stages.

Protocol 2: Batch Effect Correction and Meta-Analysis

Purpose: To combine datasets from multiple studies while controlling for batch effects and false positives.

Materials:

- Multiple microbiome datasets from different studies

- Consistent taxonomic profiling across datasets

- Clinical or phenotypic metadata

Procedure:

Individual Study Processing

- Process each dataset independently through standardized pipeline

- Generate relative abundance profiles for each study

- Perform quality control and filtering specific to each dataset

Percentile Normalization Approach [17]

- For case-control studies, convert case abundances to percentiles of control distribution:

Batch Effect Correction

- Apply ComBat or limma batch correction when appropriate

- Use negative controls to estimate batch effect size

- Validate correction with visualization (PCA, PCoA)

Meta-Analysis Implementation

- Apply Fisher's or Stouffer's method for p-value combination

- Use random-effects models when heterogeneity is present

- Apply FDR correction to meta-analysis results

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Robust Microbiome Analysis

| Resource | Function | Application Context | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| ANCOM-BC R Package | Bias-corrected composition analysis | Differential abundance with sampling fraction estimation | Available on Bioconductor |

| ALDEx2 with Scale Models | Accounting for scale uncertainty | Studies with variable microbial load | Bioconductor, with scaleModel parameter |

| Percentile Normalization Scripts | Batch effect correction in case-control studies | Multi-study meta-analyses | Python and QIIME 2 plugins available [17] |

| MAP2B Profiler | Reduction of false positive taxa identification | Whole metagenome sequencing studies | Standalone software for taxonomic profiling [19] |

| Mock Communities | Quality control and false positive estimation | Validating sequencing accuracy and analysis pipelines | Commercial standards (ZymoBIOMICS) |

Advanced Considerations and Emerging Solutions

Absolute Abundance Quantification

Recent advances in quantitative microbiome profiling highlight the limitations of relative abundance data. Methods that incorporate absolute abundance through flow cytometry, quantitative PCR, or spike-in standards can dramatically improve significance and reduce false positives. In antibiotic treatment studies, absolute abundance calculation uncovered significant changes in five families and ten genera that were not detected by standard relative abundance analysis [20]. This approach addresses the fundamental compositionality problem where changes in one taxon's abundance artificially appear to change relative abundances of all other taxa.

Integrated Multi-Omics Frameworks

Integrating microbiome data with metabolomic profiles introduces additional multiple testing challenges. Benchmark studies of 19 integrative methods revealed that proper handling of both compositionality and multiplicity is essential for robust microbe-metabolite association detection [12]. The best-performing approaches included sparse Canonical Correlation Analysis (sCCA) and Compositional LASSO, which simultaneously address feature selection and multiple testing burden.

Scale Uncertainty Incorporation

The updated ALDEx2 software introduces scale models as a generalization of normalizations, allowing researchers to model potential errors in assumptions about microbial load [18]. This approach can drastically reduce false positive rates compared to standard normalization-based methods. When scale information is available from qPCR or flow cytometry, incorporating these data as priors in scale models further improves accuracy.

Figure 2: Scale Uncertainty Integration Framework. Incorporating scale information and modeling uncertainty dramatically reduces false positives.

Uncorrected multiplicity remains a pervasive problem in microbiome research, with studies demonstrating that false positive rates can exceed 50% when using inappropriate methods [2] [18]. The compositional nature of microbiome data further complicates statistical analysis, requiring specialized methods that go standard multiple testing corrections. Through implementation of compositionally aware differential abundance methods, proper FDR control, batch effect correction, and scale uncertainty modeling, researchers can dramatically improve the reproducibility and biological validity of their findings. As microbiome research continues to evolve toward multi-omics integration and clinical applications, rigorous statistical practices for false positive control will become increasingly critical for generating actionable insights.

High-throughput sequencing in microbiome studies routinely measures the relative abundance of hundreds to thousands of microbial taxa, genes, or functional pathways simultaneously. This creates a fundamental statistical challenge: when conducting thousands of statistical tests, the probability of falsely declaring significance (Type I error) increases dramatically. Without proper correction, standard significance thresholds (e.g., p < 0.05) yield excessive false positives; with overly stringent correction, true biological signals may be lost. This article outlines strategic study design principles and analytical frameworks that minimize multiple testing burden from the outset, thereby enhancing the robustness and reproducibility of microbiome research findings.

The core challenge stems from microbiome data's unique characteristics: compositional nature, sparsity (excess zeros), over-dispersion, and high dimensionality [21] [2]. A recent large-scale evaluation of 14 differential abundance methods across 38 datasets revealed that these tools identify drastically different numbers and sets of significant taxa, confirming that analytical choices profoundly impact biological interpretations [2]. Planning analysis to minimize multiple testing burden is therefore not merely a statistical formality but a fundamental requirement for valid scientific inference.

Core Principles for Minimizing Multiple Testing Burden

Strategic Study Design and Hypothesis Formulation

- Define Focused Research Hypotheses: Begin with precise, biologically driven hypotheses rather than unrestricted exploratory searches. Studies specifically testing associations between microbiome features and predefined clinical, environmental, or intervention conditions inherently reduce the feature space requiring statistical testing [21].

- Incorporate Preliminary Data: Use pilot studies or published literature to prioritize specific microbial taxa, functional pathways, or metabolites for targeted analysis. This a priori feature selection based on biological evidence dramatically reduces the number of tests compared to agnostic all-features approaches.

- Optimize Sample Size: Conduct power analyses specific to microbiome data properties. Inadequate sample size remains a primary cause of both false positives and false negatives in high-dimensional settings, as underpowered studies produce unstable effect size estimates [2].

Data Reduction and Feature Prioritization Strategies

- Biological Aggregation: Analyze data at higher taxonomic ranks (e.g., genus or family instead of amplicon sequence variants) when scientifically justified, substantially reducing the number of features [2].

- Prevalence Filtering: Apply independent prevalence filters (e.g., retaining features present in ≥10% of samples) before statistical testing. This removes rare features unlikely to provide reproducible signals, reducing multiple testing burden without appreciably sacrificing power [2] [22].

- Phylogenetic Aggregation: Utilize phylogenetic relationships to group evolutionarily related taxa, effectively reducing feature dimensionality while preserving biological information.

Table 1: Data Reduction Strategies and Their Impact on Multiple Testing Burden

| Strategy | Implementation | Potential Reduction in Tests | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taxonomic Aggregation | Analyze at genus level instead of ASV/OTU | 50-90% reduction | Potential loss of species-/strain-specific signals |

| Prevalence Filtering | Retain features in ≥10% of samples | 20-60% reduction | Must be independent of test statistic |

| Abundance Filtering | Retain features above mean relative abundance threshold | 30-70% reduction | Risk of eliminating biologically important low-abundance taxa |

| Phylogenetic Aggregation | Group features by evolutionary relationships | 40-80% reduction | Requires robust phylogenetic tree |

Methodological Selection for Compositional Data

Standard statistical methods assuming normally distributed data produce excessive false positives when applied to raw microbiome data [21] [2]. Instead, employ methods specifically designed for microbiome data characteristics:

- Compositional Data Analysis (CoDA) Methods: Frameworks like ALDEx2 [2] and ANCOM [2] explicitly account for the relative nature of microbiome data by analyzing log-ratios between features, preventing spurious correlations.

- Overdispersed Count Distributions: Methods using negative binomial (DESeq2) [22], zero-inflated, or hurdle models better capture the distribution of sequence counts, improving error rate control [21].

- Regularized Regression: Techniques like LASSO incorporate feature selection directly into the modeling process, automatically shrinking coefficients of non-informative features to zero [12].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: Pre-Analysis Feature Filtering and Data Transformation

This protocol outlines steps for reducing feature space before formal statistical testing.

Materials and Reagents

- Software Requirements: R or Python with appropriate packages (phyloseq, microbiome, QIIME 2)

- Input Data: Feature table (OTU/ASV table), taxonomic assignments, sample metadata

- Reference Databases: SILVA, Greengenes, or GTDB for taxonomic aggregation

Procedure

- Taxonomic Aggregation: Collapse features to genus level using taxonomic assignment information.

- Prevalence Filtering: Remove features with prevalence below 10% (present in <10% of samples).

- Abundance Filtering: Remove features with mean relative abundance below 0.01%.

- Compositional Transformation: Apply centered log-ratio (CLR) transformation with pseudo-count of 0.5 to address compositionality.

- Batch Effect Assessment: Visualize principal coordinates to identify potential batch effects requiring adjustment.

Validation

- Compare beta-diversity ordinations before and after filtering to ensure major biological patterns are preserved.

- Document the number of features removed at each step for reproducibility.

Protocol 2: Integrated Differential Abundance Analysis Framework

This protocol employs a consensus approach to differential abundance testing, enhancing result robustness.

Materials and Reagents

- Statistical Software: R with packages DESeq2, ANCOM-BC, LinDA, or Melody

- Normalization Methods: CSS, TMM, or rarefaction (with caution)

- Multiple Testing Correction: Benjamini-Hochberg FDR, q-value

Procedure

- Method Selection: Apply at least two conceptually distinct differential abundance methods (e.g., DESeq2 + ANCOM-BC).

- Independent Filtering: Apply prevalence/abundance filters independently to each method's input.

- Statistical Testing: Run each method with appropriate parameters for your study design.

- Result Integration: Identify differentially abundant features consistently detected across multiple methods.

- Multiple Testing Correction: Apply FDR correction within each method, then intersect results.

Validation

- Assess false discovery rate using negative control features or permutation tests.

- Compare effect sizes and directions across methods for consistent features.

- Report the number of features identified by each method alone and in combination.

Table 2: Comparison of Differential Abundance Methods for Microbiome Data

| Method | Statistical Approach | Handles Compositionality | Zero Inflation | Recommended Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DESeq2 | Negative binomial model | No | Moderate | Large effect sizes, count-based analysis |

| ANCOM-BC | Linear model with bias correction | Yes | Moderate | Conservative analysis, clinical applications |

| ALDEx2 | CLR transformation + Wilcoxon | Yes | Good | Small sample sizes, compositional focus |

| LinDA | Linear model on log-ratios | Yes | Good | General-purpose, compositionally aware |

| Melody | Meta-analysis framework | Yes | Good | Cross-study validation, generalizable signatures |

Protocol 3: Multi-Omic Integration with Dimensionality Reduction

For studies integrating microbiome with metabolomics or other omics data, this protocol reduces multiple testing burden through dimension reduction.

Materials and Reagents

- Integration Methods: Sparse PLS, MOFA2, Procrustes analysis, Mantel test

- Data Types: Microbiome (CLR-transformed), metabolomics (log-transformed, scaled)

- Software: mixOmics, MOFA2, vegan packages

Procedure

- Data Preprocessing: Apply CLR transformation to microbiome data; log-transform and scale metabolomics data.

- Global Association Testing: Use Mantel test or Procrustes analysis to test overall association between omics datasets.

- Dimension Reduction: Apply sPLS or DIABLO to identify latent components explaining covariation.

- Feature Selection: Extract features with high loadings on significant components.

- Targeted Testing: Conduct focused statistical testing only on selected feature subsets.

Validation

- Assess stability of selected features through bootstrap resampling.

- Validate findings in independent cohort when possible.

- Perform pathway enrichment analysis on selected features for biological coherence.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Microbiome Data Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Melody | Meta-analysis framework | Identifying generalizable microbial signatures | Compositionality-aware, avoids batch effects [23] |

| MMUPHin | Batch effect correction | Cross-study analysis | Preserves biological signal while removing technical artifacts |

| ANCOM-BC | Differential abundance testing | Case-control studies | Accounts for compositionality, provides FDR control |

| DESeq2 | Differential abundance testing | RNA-Seq and microbiome data | Negative binomial model, robust to varying sequencing depth |

| mixOmics | Multi-omics integration | Microbiome-metabolite studies | sPLS, DIABLO for dimension reduction |

| PERMANOVA | Community-level differences | Beta-diversity analysis | Multivariate hypothesis testing with FDR control |

| QIIME 2 | Data processing pipeline | 16S and metagenomic analysis | From raw sequences to diversity analyses |

Minimizing multiple testing burden requires forethought in study design, appropriate analytical method selection, and strategic feature space reduction. By implementing the principles and protocols outlined here, researchers can substantially enhance the validity, reproducibility, and biological interpretability of microbiome study findings. The rapidly evolving methodological landscape continues to provide new compositionally-aware tools that better respect microbiome data's unique structure, offering improved error control without sacrificing biological discovery. As the field progresses toward standardized analytical frameworks, building multiple testing prevention into study design from the outset will remain essential for generating clinically and biologically meaningful insights from complex microbiome datasets.

In microbiome research, a clearly defined hypothesis space is critical for generating robust, biologically interpretable, and statistically sound conclusions. The analytical journey often progresses from broad, community-level inquiries to focused, taxon-specific questions, each requiring distinct statistical approaches and multiple testing corrections. Microbial community data are characterized by high dimensionality, compositionality, over-dispersion, and sparsity with excess zeros [24] [21] [1]. These characteristics, combined with the inherent phylogenetic relationships between microbial taxa, create a complex multiple testing burden that must be carefully managed to avoid both false discoveries and loss of statistical power [14]. This protocol outlines a structured framework for defining your hypothesis space and selecting appropriate statistical methods that align with your research questions, from global community tests to targeted taxon-specific analyses, while properly addressing the challenges of multiple comparisons.

The concept of a hierarchical hypothesis space is particularly powerful in microbiome analysis because it mirrors the biological structure of microbial communities. Rather than treating all taxonomic features as independent entities, this approach recognizes that microbial taxa exist within a phylogenetic context where related organisms may share ecological functions and respond similarly to environmental perturbations [14]. By structuring your analysis to first assess global patterns then progressively drill down to finer taxonomic resolutions, you can create a more statistically efficient and biologically informed analytical pipeline. This structured approach helps researchers avoid the common pitfall of conducting thousands of independent tests without proper correction, while also providing a logical framework for interpreting results in the context of microbial ecology and evolution.

Defining Your Analytical Workflow: From Global to Specific

The Hypothesis Testing Hierarchy

A structured, multi-layered approach to microbiome differential abundance analysis allows researchers to navigate the multiple comparisons problem while maintaining statistical power. The following workflow diagram illustrates this hierarchical process:

This workflow begins with community-level analysis to determine if global microbial community structure differs between groups, proceeds to intermediate phylogenetic tests that leverage taxonomic relationships, and culminates in taxon-specific analysis to identify individual differentially abundant features. Each stage employs statistical methods appropriate for that level of resolution and applies multiple testing corrections tailored to the hypothesis space.

Community-Level Global Tests

Global community tests evaluate whether overall microbial community composition differs significantly between experimental groups or conditions. These methods analyze the complete multivariate dataset without first testing individual taxa, thereby avoiding the multiple comparisons problem at the feature level.

Table 1: Community-Level Global Test Methods

| Method | Statistical Approach | Data Input | Hypothesis Tested | Multiple Comparisons Correction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PERMANOVA | Non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance based on distance matrices | Distance matrix (Bray-Curtis, UniFrac) | No overall community composition difference between groups | Not applicable (single global test) |

| Mantel Test | Correlation between distance matrices | Two distance matrices | No association between community dissimilarity and environmental gradient | Not applicable (single global test) |

| Beta Dispersion | Analysis of multivariate dispersion | Distance matrix | No difference in group homogeneity (dispersion) | Not applicable (single global test) |

Experimental Protocol: Community-Level Analysis

Data Preparation: Begin with a filtered feature table (ASV/OTU table). Calculate appropriate distance matrices using metrics such as:

- Bray-Curtis (for general composition)

- Weighted UniFrac (for phylogenetic-aware abundance-weighted differences)

- Unweighted UniFrac (for phylogenetic-aware presence-absence differences)

PERMANOVA Implementation:

Interpretation: A significant PERMANOVA result (typically p < 0.05) indicates that microbial community composition differs between groups. The R² value indicates the effect size - the proportion of variance explained by the grouping factor.

Follow-up Analysis: If PERMANOVA is significant, proceed to intermediate phylogenetic tests. If not significant, consider whether the study has sufficient power or whether effects might be limited to specific taxonomic subsets.

Intermediate Phylogenetic Tests

Intermediate-level tests leverage the hierarchical structure of microbial taxonomy to reduce the multiple testing burden while maintaining phylogenetic context. These methods test hypotheses at multiple taxonomic levels, from phylum to genus, capitalizing on the biological insight that related taxa may respond similarly to experimental conditions.

Table 2: Intermediate Phylogenetic Test Methods

| Method | Statistical Approach | Taxonomic Utilization | Multiple Comparisons Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| mi-Mic | Combines ANOVA on cladogram of means with Mann-Whitney tests on significant paths | Phylogenetic tree or taxonomic hierarchy | FDR correction only on significant paths and leaves |

| PhAAT | Constructs Branch-Abundance matrix from phylogenetic tree | Phylogenetic tree | Filtering and clustering of related branches |

| structSSI | Hierarchical FDR control along phylogenetic tree | Phylogenetic tree | Children hypotheses tested only if parent is significant |

| ada-ANCOM | Zero-inflated Dirichlet-tree multinomial model | Phylogenetic tree | Bayesian formulation with posterior transformation |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing mi-Mic

Data Preprocessing:

A Priori Nested ANOVA Test:

Post-hoc Phylogeny-Aware Testing:

Result Integration: mi-Mic returns significant taxa identified through both the path analysis and leaf-level testing, providing a phylogenetically informed set of differentially abundant features.

Taxon-Specific Differential Abundance Analysis

At the finest resolution of the hypothesis space, taxon-specific methods test for differential abundance of individual microbial features. These methods must contend with the high dimensionality of microbiome data, where thousands of individual taxa are tested simultaneously.

Table 3: Taxon-Specific Differential Abundance Methods

| Method | Statistical Foundation | Data Distribution | Compositionality Awareness | Multiple Testing Correction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALDEx2 | Monte Carlo sampling from Dirichlet distribution | Compositional count data | Yes (centered log-ratio transformation) | Benjamini-Hochberg FDR |

| ANCOM-BC | Linear models with bias correction | Compositional count data | Yes (additive log-ratio transformation) | Bonferroni correction |

| DESeq2 | Negative binomial models | Count data | Limited (requires careful interpretation) | Benjamini-Hochberg FDR |

| edgeR | Negative binomial models | Count data | Limited (requires careful interpretation) | Benjamini-Hochberg FDR |

| LEfSe | Kruskal-Wallis with LDA effect size | Relative abundance | Limited | Not applicable (uses LDA effect size cutoff) |

Experimental Protocol: Comparative Differential Abundance Analysis

Data Normalization Selection: Different methods require different normalization approaches:

- DESeq2/edgeR: Use their built-in normalization (median of ratios/TMM)

- ALDEx2: Uses centered log-ratio transformation internally

- ANCOM-BC: Handles compositionality through log-ratio transformations

Multi-Method Implementation: Given the variability in results across methods [2], implement a consensus approach:

Consensus Identification: Identify taxa consistently significant across multiple methods to increase confidence in results. For example, consider features significant in at least 2 of 3 methods applied.

Effect Size Evaluation: For significant taxa, evaluate effect sizes (fold changes, LDA scores, or CLR differences) to assess biological relevance beyond statistical significance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Microbiome Differential Abundance Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| QIIME 2 | Bioinformatics pipeline | Data preprocessing from raw sequences to feature table | Command-line, Python |

| DADA2 | R package | High-resolution amplicon variant calling | R |

| phyloseq | R package | Data organization and visualization for microbiome data | R |

| vegan | R package | Community ecology analysis including PERMANOVA | R |

| DESeq2 | R package | Differential abundance analysis using negative binomial models | R |

| ALDEx2 | R package | Compositional differential abundance analysis | R |

| ANCOM-BC | R package | Compositional differential abundance with bias correction | R |

| mi-Mic | R package | Multi-layer phylogenetic differential abundance testing | R |

| MIPMLP | Pipeline | Standardized normalization and preprocessing | Online platform, R |

| Eliapixant | Bench Chemicals | ||

| endo-BCN-PEG2-acid | endo-BCN-PEG2-acid, MF:C18H27NO6, MW:353.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Defining a structured hypothesis space from global community tests to taxon-specific inquiries provides a powerful framework for microbiome differential abundance analysis. This hierarchical approach enables researchers to navigate the multiple comparisons problem while maintaining statistical power and biological interpretability. By beginning with community-level tests, proceeding through intermediate phylogenetic analyses, and culminating in carefully corrected taxon-specific tests, researchers can generate robust conclusions that account for both the statistical challenges and biological reality of microbiome data. The consensus approach across multiple differential abundance methods further enhances confidence in results, as different methods can produce substantially different findings on the same datasets [2]. Implementing this structured workflow ensures that microbiome analyses are both statistically rigorous and biologically informative, advancing our understanding of microbial communities in health and disease.

Advanced Correction Methods in Practice: From Standard FDR Control to Phylogeny-Aware Approaches

In high-throughput microbiome studies, researchers commonly test the differential abundance of hundreds to thousands of microbial taxa simultaneously. This massive multiple testing problem dramatically increases the probability of false positive findings, where taxa are incorrectly identified as associated with a condition or intervention. Traditional approaches like the Bonferroni correction that control the family-wise error rate (FWER) are often overly conservative, leading to many missed discoveries (Type II errors) [9]. In microbiome research, where effects can be subtle and signals sparse, this severely limits statistical power.

The false discovery rate (FDR), defined as the expected proportion of false discoveries among all rejected hypotheses, has emerged as a more practical error rate for large-scale microbiome studies [25] [26]. The Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) procedure, introduced in 1995, was the first method developed to control the FDR and remains one of the most widely used approaches due to its simplicity and robustness [27] [25]. By allowing a controlled proportion of false positives, FDR methods maintain higher statistical power while still providing meaningful error control, making them particularly suitable for exploratory microbiome analyses where findings are typically validated through follow-up experiments [9].

Theoretical Foundations of the Benjamini-Hochberg Procedure

Definition and Mathematical Formulation

The Benjamini-Hochberg procedure addresses the multiple testing problem by controlling the expected proportion of false discoveries. For m simultaneous hypothesis tests, let V be the number of false positives and R be the total number of rejected null hypotheses. The FDR is defined as FDR = E[V/R | R > 0] × P(R > 0) [25]. The BH procedure ensures that at a desired FDR level α, the expected proportion of false discoveries among all significant findings does not exceed α [27].

The mathematical procedure operates as follows. Consider testing m hypotheses based on their corresponding p-values: p~1~, p~2~, ..., p~m~. Let p~(~1~)~ ≤ p~(~2~)~ ≤ ... ≤ p~(~m~)~ represent the ordered p-values. The BH procedure identifies the largest k such that:

p~(~k~)~ ≤ (k / m) × α

All hypotheses with p-values ≤ p~(~k~)~ are declared statistically significant at the FDR level α [27] [25]. This step-up procedure is less conservative than FWER-controlling methods while maintaining meaningful error control.

Comparison of Multiple Testing Correction Approaches

Table 1: Comparison of multiple testing correction methods

| Method | Error Rate Controlled | Key Characteristic | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| No correction | Per-comparison error rate | No adjustment for multiple tests | Single hypothesis testing |

| Bonferroni | Family-wise error rate (FWER) | Very conservative; protects against any false positive | Confirmatory studies with few tests |

| Benjamini-Hochberg | False discovery rate (FDR) | Less conservative; allows some false positives | Exploratory microbiome studies with many tests |

| Benjamini-Yekutieli | FDR under arbitrary dependence | More conservative than BH; handles any dependency structure | Tests with known negative correlations |

The fundamental trade-off between these methods involves balancing Type I error (false positives) against Type II error (false negatives) [28]. In microbiome applications, where researchers often seek promising candidates for further validation, the BH procedure's tolerance for a controlled fraction of false positives in exchange for increased power makes it particularly advantageous [9].

Standard Benjamini-Hochberg Implementation Protocol

Step-by-Step Computational Procedure

The BH procedure can be implemented through the following step-by-step protocol:

Collect and sort p-values: Compute raw p-values for all m hypothesis tests (e.g., from statistical tests for differential abundance). Sort these p-values in ascending order: p~(~1~)~ ≤ p~(~2~)~ ≤ ... ≤ p~(~m~)~ [27].

Calculate critical values: For each ordered p-value p~(~i~)~, compute the corresponding BH critical value as (i / m) × α, where α is the desired FDR level (typically 0.05 or 0.1) [27] [28].

Identify significant tests: Find the largest index k where p~(~k~)~ ≤ (k / m) × α. All hypotheses with p-values ≤ p~(~k~)~ are declared statistically significant [25].

Calculate adjusted p-values (optional): The BH-adjusted p-value for the i-th ordered test is calculated as p~(i)~ = min{1, min~j≥i~ {(m × p~(~j~)~) / j}} [27]. These adjusted p-values can be compared directly to the FDR threshold α.

The following workflow illustrates this step-by-step procedure:

Practical Implementation Across Software Platforms

Table 2: Implementation of BH procedure across computational platforms

| Platform | Function/Command | Required Input | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| R | p.adjust(pvalues, method="BH") |

Vector of p-values | pvalues: numeric vector of p-values |

| Python | stats.false_discovery_control(pvalues) |

Array of p-values | method: FDR control method (SciPy 1.11+) |

| Excel/Sheets | Manual calculation | Column of p-values | Requires rank and formula calculations |

R Implementation:

Python Implementation:

Excel/Google Sheets Implementation:

- Place p-values in column A

- Calculate ranks in column B:

=RANK.EQ(A2,$A$2:$A$7,1)+COUNTIF($A$2:$A$7,A2)-1 - Calculate (p × m / k) in column C:

=A2*COUNT($A$2:$A$7)/B2 - Calculate adjusted p-values in column D:

=MIN(1,MINIFS($C$2:$C$7,$B$2:$B$7,">="&B2))[27]

Advanced FDR Methodologies for Microbiome Data

Challenges of Microbiome Data and Discrete FDR

Microbiome data presents unique challenges for FDR control due to its inherent sparsity (many zero counts) and the discreteness of test statistics, particularly with small sample sizes. These characteristics can make the standard BH procedure overly conservative, reducing power to detect genuine differential abundance [8].

The discrete FDR (DS-FDR) method addresses these limitations by exploiting the discrete nature of the test statistics through permutation-based procedures. In simulations comparing DS-FDR to standard BH and filtered BH (FBH) approaches, DS-FDR demonstrated substantially higher power while maintaining FDR control, particularly with small sample sizes. When sample size was ≤20, DS-FDR identified 24 more taxa than BH and 16 more taxa than FBH on average [8].

For studies with ordered groups (e.g., disease stages), the mixed directional FDR (mdFDR) framework extends standard approaches to handle pattern analyses across multiple groups, providing greater power than performing separate pairwise tests [29].

Covariate-Integrated and Structure-Adaptive Methods

Modern FDR methods can increase power by incorporating complementary information as informative covariates. These approaches leverage the observation that statistical power varies across tests, and covariates can help prioritize hypotheses more likely to be true discoveries [26].

The two-stage massMap framework specifically designed for microbiome data utilizes taxonomic structure to enhance power. In the first stage, groups of taxa at a higher taxonomic rank are tested for association using a powerful microbial group test (OMiAT). In the second stage, only taxa within significant groups are tested at the target rank, with advanced FDR control methods (hierarchical BH or selected subset testing) applied to account for the two-stage structure [10].

Simulation studies demonstrate that massMap achieves higher statistical power than traditional one-stage approaches while controlling the FDR at desired levels, detecting more associated species with smaller adjusted p-values [10].

Experimental Protocol for Method Comparison in Microbiome Studies

Benchmarking Framework for FDR Methods

To evaluate the performance of different FDR control methods in microbiome differential abundance analysis, researchers can implement the following experimental protocol:

Data Preparation:

- Obtain or simulate microbiome count data with known ground truth (truly differential and non-differential taxa)

- For real data applications, use datasets from public repositories (e.g., Qiita, MG-RAST) with appropriate sample sizes

- Apply prevalence filtering if desired (e.g., retain taxa present in ≥10% of samples) [2]

Differential Abundance Testing:

- Apply statistical tests (e.g., Wilcoxon, DESeq2, ANCOM-BC, LinDA) to generate raw p-values for each taxon

- Implement multiple FDR control methods:

- Standard BH procedure (

p.adjustin R) - Storey's q-value (

qvaluepackage in R) - DS-FDR for discrete data

- Covariate-informed methods (IHW, FDRreg)

- Structure-aware methods (massMap for taxonomic data)

- Standard BH procedure (

Performance Evaluation:

- Calculate false discovery proportions and power using known ground truth

- Compare number of significant taxa identified by each method

- Assess consistency of results across methods and datasets [2]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential computational tools for FDR control in microbiome analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| R Statistical Environment | Primary platform for statistical analysis | Comprehensive ecosystem for multiple testing correction |

| MicrobiomeAnalyst | Web-based platform for microbiome analysis | Includes multiple differential abundance testing methods with FDR correction |

| SciPy (v1.11+) | Python scientific computing library | Provides false_discovery_control function for FDR adjustment |

| massMap R package | Two-stage microbial association mapping | Implements advanced FDR control using taxonomic structure |

| IHW R package | Covariate-informed FDR control | Uses independent hypothesis weighting for increased power |

Comparative Performance and Applications

Empirical Comparisons Across Microbiome Datasets

Large-scale benchmarking studies evaluating 14 differential abundance methods across 38 microbiome datasets revealed substantial variability in the number of significant taxa identified by different approaches. The percentage of significant amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) ranged from 0.8% to 40.5% across methods, highlighting the substantial impact of methodological choices on biological interpretations [2].

Methods such as ALDEx2 and ANCOM-II were found to produce the most consistent results across studies and agreed best with the intersect of results from different approaches [2]. Based on these findings, researchers are recommended to use a consensus approach based on multiple differential abundance methods to ensure robust biological interpretations.

Practical Recommendations for Microbiome Researchers

Standard applications: For routine differential abundance analysis, the standard BH procedure provides a robust, well-understood approach for FDR control.

Small sample sizes or sparse data: When sample size is small (n < 20) or data is extremely sparse, DS-FDR provides improved power while maintaining FDR control [8].

Structured hypotheses: For data with inherent structure (taxonomic, phylogenetic), structure-aware methods like massMap leverage this information to enhance discoveries [10].

Exploratory analyses: In discovery-phase research, consider using covariate-informed FDR methods or running multiple FDR procedures to identify stable findings.

Validation: Always validate key findings through independent cohorts or experimental approaches, particularly when using less conservative FDR methods.

The choice of FDR control method should align with study objectives, data characteristics, and validation resources. While modern methods offer power advantages, the standard Benjamini-Hochberg procedure remains a versatile and reliable choice for most microbiome research applications.

Differential abundance (DA) analysis represents a cornerstone of microbiome research, enabling the identification of microbial taxa whose abundances differ under varying experimental conditions or clinical phenotypes. While numerous statistical methods exist for two-group comparisons, many microbiome studies involve complex designs with multiple groups, ordered factors, and longitudinal sampling [30] [29]. The ANCOM-BC2 methodology (Analysis of Compositions of Microbiomes with Bias Correction 2) represents a significant advancement in this domain, providing a comprehensive framework for multi-group analyses with proper false discovery rate control [30] [31]. This method addresses critical limitations of standard pairwise approaches, which are inefficient in terms of power and false discovery rates when applied to multiple comparisons [29].

Within the broader context of microbiome statistical analysis and multiple comparisons correction research, ANCOM-BC2 fills a crucial methodological gap by extending the popular ANCOM-BC approach to handle complex experimental designs while incorporating enhanced bias correction, variance regularization, and sensitivity analyses [31] [32]. This protocol details the application of ANCOM-BC2 for multi-group comparisons with covariate adjustment, providing researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with practical guidance for implementation and interpretation.

Theoretical Foundation

Methodological Advancements

ANCOM-BC2 introduces several key improvements over existing differential abundance methods. First, it estimates and corrects for both sample-specific biases (e.g., sampling fractions) and taxon-specific biases (e.g., sequencing efficiencies) that can confound results [31] [32]. This dual correction addresses important technical variations, such as the underrepresentation of gram-positive bacteria due to their stronger cell walls, which are harder to lyse during DNA extraction [30] [29].