Navigating Zero-Inflation and Overdispersion: A Statistical Guide for Robust Microbiome Data Analysis

Microbiome data from high-throughput sequencing are characterized by zero-inflation and overdispersion, posing significant challenges for robust statistical analysis in biomedical and clinical research.

Navigating Zero-Inflation and Overdispersion: A Statistical Guide for Robust Microbiome Data Analysis

Abstract

Microbiome data from high-throughput sequencing are characterized by zero-inflation and overdispersion, posing significant challenges for robust statistical analysis in biomedical and clinical research. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals, addressing these data intricacies from foundational concepts to advanced methodologies. We explore the sources and implications of these characteristics, detail a suite of specialized statistical models—including zero-inflated and hurdle models—for differential abundance and integrative analysis, and offer best practices for data preprocessing and model selection. Furthermore, we review validation techniques and comparative performance of competing methods through simulation studies and real-world applications, empowering scientists to derive reliable biological insights from their microbiome studies.

The Nature of the Challenge: Understanding Zero-Inflation and Overdispersion in Microbiome Data

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What are the main types of high-throughput sequencing for microbiome studies? Researchers primarily use two approaches [1] [2]:

- Targeted Amplicon Sequencing (e.g., 16S rRNA, ITS): This method uses PCR to amplify and sequence specific marker genes. It is a cost-effective and high-throughput method for profiling microbial community composition and diversity, typically down to the genus level.

- Shotgun Metagenomics: This approach involves sequencing all the DNA fragments in a sample. It is more expensive but provides a higher-resolution view of the community, enabling species- or strain-level identification and insights into the functional potential (gene content) of the microbiome.

2. Why is microbiome data often characterized by an abundance of zeros? The zeros in a microbiome dataset, known as zero-inflation, arise from two main processes [3]:

- Structural Zeros: These represent a true absence of a microbe in a sample because the subject is not at risk for hosting that particular taxon (e.g., an obligate anaerobe in an oxygen-rich environment).

- Sampling Zeros: These are false absences that occur due to sampling variability, where a microbe is present in the ecosystem but was not captured in the specific sample taken, often because it is in very low abundance.

3. What causes overdispersion in microbiome sequencing data? Overdispersion occurs when the variance in the data is much larger than the mean. In microbiome studies, this is common and can be caused by [3]:

- Biological Variation: Genuine, large differences in microbial abundances between different subjects or sample groups.

- Technical Variation: Artifacts introduced during the experimental workflow, including PCR amplification bias, sequencing depth differences, and contamination from low-biomass samples [1] [4].

4. What are common troubleshooting issues in sequencing preparation? Library preparation is a critical source of potential problems. Common issues include [5]:

- Low Library Yield: Often caused by poor input DNA/RNA quality, contaminants inhibiting enzymes, or inaccurate quantification.

- Adapter Dimers: Sharp peaks at ~70-90 bp in an electropherogram indicate inefficient ligation or overly aggressive purification, where adapter molecules ligate to each other instead of the target DNA.

- Over-amplification: Too many PCR cycles can introduce duplicates and size biases, reducing library complexity.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Levels of Zero-Inflation and Overdispersion in Count Data Background: Standard statistical models like the Poisson regression assume the mean and variance of count data (e.g., OTU or ASV counts) are equal. Microbiome data consistently violate this assumption, requiring specialized models [3] [6].

Solution: Implement Advanced Statistical Models The table below summarizes appropriate models for analyzing overdispersed and zero-inflated count data.

| Model | Best For | Key Assumption | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative Binomial (NB) | Overdispersed data without excess zeros. [3] | All zeros are sampling zeros. [3] | Coefficients can be exponentiated as Rate Ratios (RR). [3] |

| Zero-Inflated Negative Binomial (ZINB) | Data with both zero-inflation and overdispersion. [3] [6] | Zeros come from two latent groups: a "always-zero" group and an "at-risk" group. [3] | Logistic model part outputs Odds Ratios (OR) for structural zeros; count model part outputs RR for counts. [3] |

| Hurdle Model (HUNB) | Data with both zero-inflation and overdispersion. [3] | All zeros are generated from a single, structural process. [3] | Logistic model discriminates zeros from non-zeros; a truncated count model (e.g., truncated NB) models positive counts. [3] |

How to Choose: The choice between ZINB and Hurdle models should depend on your research question and the assumed nature of the zeros. The ZINB model is conceptually useful when your population logically contains a sub-group that is not at risk for a microbe (e.g., non-smokers in a study of smoking frequency). The Hurdle model is appropriate when the entire population is at risk, but a process determines whether a count is zero or positive (e.g., the number of non-smoking days among smokers) [3].

Problem: Inconsistent Microbiota Profiles Due to Technical Bias Background: The choice of sequencing platform, the hypervariable region of the 16S rRNA gene that is targeted, and the bioinformatic pipeline used for analysis can all introduce variability, making results across studies difficult to compare [4].

Solution: Adopt Rigorous Experimental and Analytical Controls

- Wet-Lab Controls: Always include control samples in your sequencing run to identify contamination and artifacts [1].

- Water Blank: Controls for nucleic acid contamination in your reagents ("kitome").

- Mock Community: A mixture of DNA from known microbes. This is essential for validating your entire workflow, from DNA extraction to bioinformatic analysis, and for identifying systematic biases [1].

- Bioinformatic Controls: To improve consistency, consider moving beyond short-read amplicon sequencing.

- Full-length 16S rRNA sequencing using third-generation sequencers (PacBio, Nanopore) can provide species-level resolution that short reads miss [4] [2].

- Paired-end sequencing for 16S amplicons is critical. Ensure the read length is sufficient for the paired reads to overlap completely, which reduces uncorrected sequence errors [1].

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential materials and their functions for a standard 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing workflow.

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Primers (e.g., V4 16S) [1] | Target and amplify a specific hypervariable region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene for sequencing. |

| Mock Community [1] | A defined mix of genomic DNA from known bacterial strains. Serves as a positive control to assess accuracy, precision, and bias in the wet-lab and bioinformatic pipeline. |

| Demethylase Enzymes [7] | Used in specialized tRNA-seq (DM-tRNA-seq) to remove specific tRNA modifications, allowing for more accurate sequencing of tRNA transcripts and enabling physiological studies of the microbiome. |

| Thermostable Group II Intron Reverse Transcriptase (TGIRT) [7] | A reverse transcriptase that can read through rigid structures and many base modifications in RNA, crucial for obtaining full-length sequences in tRNA-seq and other modification-rich contexts. |

Experimental Workflows and Data Relationships

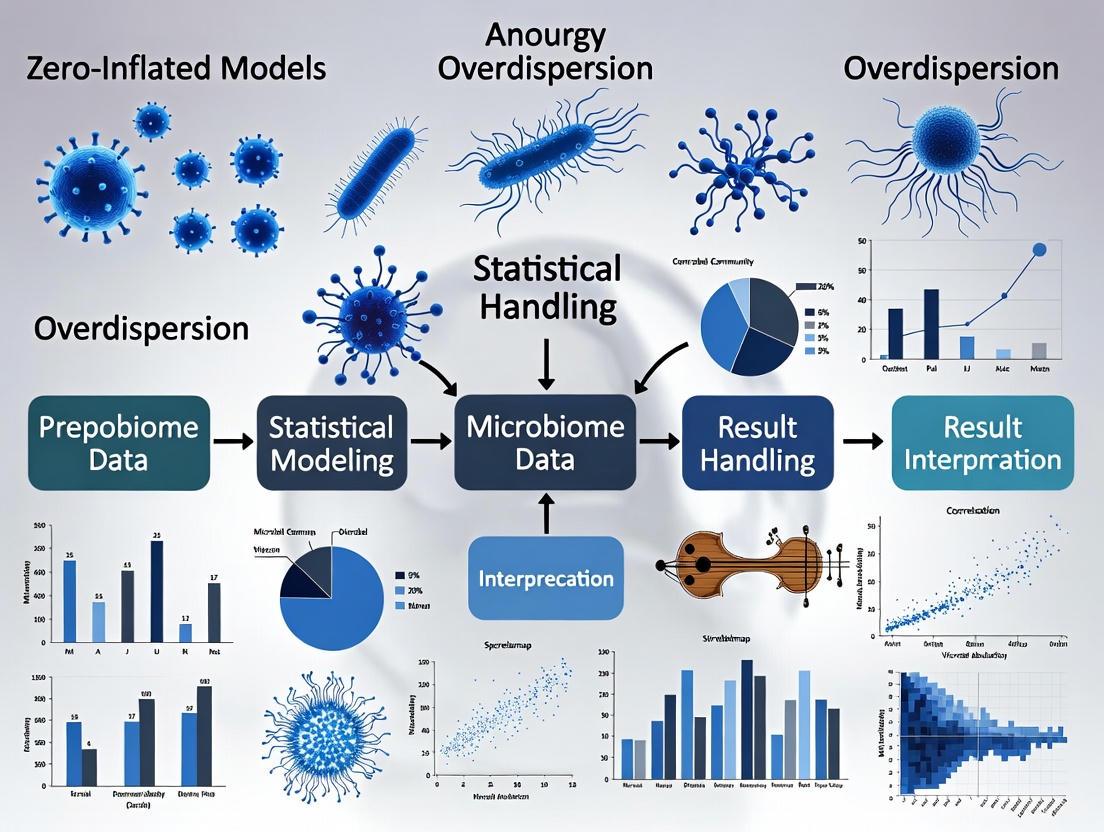

The following diagram illustrates the logical pathway from raw sequencing data through the characteristic challenges to the final statistical modeling options.

The workflow for obtaining microbiome data is complex, and choices at the wet-lab stage directly influence the characteristics of the final dataset. The diagram below outlines a standard 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing workflow, highlighting key steps where technical variation and bias can be introduced.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the fundamental types of zeros in microbiome sequence count data? Zeros in microbiome data are not all the same; they arise from distinct processes. The primary classification includes four types [8]:

- Sampling Zeros: Arise due to limited sequencing depth. A microbe is present in a sample but not detected because not enough reads were collected.

- Biological Zeros: Represent the true absence of a sequence from a biological system.

- Technical Zeros (Partial): Caused by experimental procedures that partially reduce countable sequences (e.g., difficulty amplifying GC-rich genes).

- Technical Zeros (Complete): Caused by experimental procedures that completely prevent a sequence from being counted (e.g., batch effects or PCR amplification bias). This is the process that zero-inflated models specifically address.

2. Why is it critical to distinguish between technical and biological zeros? Incorrectly classifying zeros can lead to flawed biological interpretations [8] [9]. Mistaking a technical zero (a microbe that was present but undetected) for a biological zero (a genuinely absent microbe) can cause false negatives in differential abundance analysis and distort the understanding of microbial community structure and its association with diseases or environmental conditions.

3. What are the main statistical challenges posed by zero-inflated microbiome data? Microbiome data is characterized by several features that complicate analysis [10] [11]:

- High Dimensionality: The number of taxa (features) vastly exceeds the number of samples.

- Compositionality: Data represents relative, not absolute, abundances.

- Over-dispersion: The variance in the data is much larger than the mean.

- Sparsity (Zero-inflation): A large proportion (often 70-95%) of the data points are zeros [12] [8]. These characteristics can cause standard statistical methods to produce invalid or misleading results, such as inflated false discovery rates.

4. How do zero-handling methods impact the identification of differentially abundant taxa? The choice of method significantly impacts results. Different statistical models can disagree substantially on which sequences are the most differentially abundant [8] [13]. For example, a standard negative binomial model might identify a sequence with a presence-absence pattern as differentially expressed, while a zero-inflated negative binomial model might attribute the pattern to "differential zero-inflation" between conditions and not call it significant. Using a consensus of multiple methods is often recommended for robust conclusions [13].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: My differential abundance analysis is yielding inconsistent results.

Potential Cause: The analysis is not adequately accounting for the specific types of zeros and over-dispersion in your dataset.

Solution: Implement a strategy that combines multiple approaches to address different aspects of the data.

Step 1: Pre-processing and Filtering Apply a prevalence filter to remove rare taxa that are uninformative for group comparisons. For instance, filter out any taxa found in fewer than 10% of samples within a dataset [13]. This reduces the multiple testing burden and removes some noise.

Step 2: Address Zero-Inflation and Group-Wise Structured Zeros Use a combined testing approach [12]:

- Use a method like DESeq2-ZINBWaVE to handle general zero-inflation and control the false discovery rate. This method incorporates observation weights based on the ZINBWaVE model.

- Separately, use DESeq2 alone to properly handle the problem of "group-wise structured zeros" (also known as perfect separation), where a taxon has all zero counts in one group and non-zero counts in another. DESeq2's penalized likelihood estimation can provide finite parameter estimates in this scenario.

Step 3: Normalize Data Appropriately Choose a normalization method that mitigates the effects of uneven sequencing depth and compositionality. Common methods include:

Step 4: Compare Results with Compositional-Aware Methods For a more robust biological interpretation, compare your results with those from compositionally aware tools like ALDEx2 or ANCOM-II, which have been shown to produce more consistent results across studies [13].

Problem: I need to denoise my microbiome data to better recover the true biological signal.

Potential Cause: The observed count data are a noisy representation of the true microbial abundance due to technical variation, including technical zeros and uneven sequencing depth.

Solution: Use a denoising method specifically designed for microbiome data's zero-inflated and over-dispersed nature.

- Protocol: Denoising with mbDenoise [9]

mbDenoise is based on a Zero-Inflated Probabilistic PCA (ZIPPCA) model.

- Model Assumption: The observed count of a taxon in a sample is generated from a Zero-Inflated Negative Binomial (ZINB) model.

- Model Components:

- The Negative Binomial component models the count data and accounts for over-dispersion.

- The point mass at zero distinguishes between technical and biological zeros.

- Sample-specific effects are included in the model to correct for unequal sequencing depth.

- A low-rank representation (via latent factors) accounts for data redundancy and correlations between microbes.

- Procedure: The method uses variational approximation to learn the latent structure of the data.

- Output: The true abundance levels are recovered using the posterior mean, which borrows information across samples and taxa.

Experimental Workflow for Zero Analysis

The diagram below illustrates a logical workflow for analyzing zero-inflated microbiome data, integrating multiple concepts from the troubleshooting guides.

Statistical Methods for Handling Zero-Inflation

Table 1: Comparison of selected statistical methods and models for zero-inflated microbiome data.

| Method / Model | Brief Description | Key Application / Strength |

|---|---|---|

| ISCAZIM [14] | An integrated framework that benchmarks and selects correlation methods based on data characteristics like zero-inflation rates. | Microbiome-metabolome association analysis. |

| DESeq2-ZINBWaVE [12] | A weighted version of DESeq2 that uses ZINBWaVE-derived weights to handle zero-inflation. | General differential abundance testing with zero-inflated counts. |

| GZIGPFA [10] | GLM-based zero-inflated generalized Poisson factor analysis for high-dimensional data. | Dimensionality reduction and analysis of over-dispersed, zero-inflated counts. |

| mbDenoise [9] | A denoising method based on a Zero-Inflated Probabilistic PCA (ZIPPCA) model. | Recovering true abundance by distinguishing technical vs. biological zeros. |

| ZINB Model [8] | A two-part model combining a negative binomial count model with a point mass at zero. | Modeling counts with zero-inflation and over-dispersion. |

| DeepInsight (Modified) [15] | Converts compositional data to images on a hypersphere for analysis with CNNs. | Handling high-dimensional, zero-inflated compositional data. |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key computational tools and resources for analyzing zero-inflated microbiome data.

| Item / Software | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|

| R Package 'pscl' [16] | Provides functions for fitting zero-inflated Poisson (ZIP) and zero-inflated negative binomial (ZINB) regression models. |

| R Package 'ZINBWaVE' [12] [8] | Generates observation weights for zero-inflated counts, which can be used by tools like DESeq2 and edgeR. |

| R Package 'Zcompositions' [15] | Implements Bayesian-multiplicative replacement methods for handling zeros in compositional data (e.g., cmultRepl function). |

| DESeq2 [12] [13] | A popular method for differential abundance analysis that uses a negative binomial model and can handle group-wise structured zeros with its penalized likelihood. |

| ALDEx2 [13] | A compositional data analysis tool that uses a centered log-ratio (CLR) transformation, often producing robust and consistent results. |

| ANCOM-II [13] | A compositional method that uses an additive log-ratio transformation to identify differentially abundant taxa. |

| mbDenoise [9] | A specialized R package for denoising microbiome data using a ZIPPCA model to recover true biological abundance. |

FAQ: Troubleshooting Overdispersion in Microbiome Data

Q1: My microbiome count data has a high proportion of zeros and its variance is much larger than its mean. What is this phenomenon and why is it a problem?

This phenomenon is called overdispersion, and when combined with an excess of zero counts, it is known as zero-inflation [3]. In microbiome data, this arises because microbial counts are characterized by:

- Compositionality: The data represents relative abundances, where an increase in one taxon necessarily causes a decrease in others [17].

- High dimensionality and sparsity: The number of taxa (features) often exceeds the number of samples, leading to many zero counts [17].

- Overdispersion: The variance of the counts significantly exceeds the mean, violating the fundamental assumption of Poisson regression where mean equals variance [3].

This is problematic because standard statistical methods like Poisson regression or normal-based models will produce biased estimates and spurious results [3]. Overdispersion inflates standard errors, compromising hypothesis tests and potentially leading to incorrect biological inferences about microbial abundance and relationships [3].

Q2: How can I diagnostically confirm overdispersion and zero-inflation in my dataset?

You can confirm this through a combination of descriptive statistics and formal model comparisons.

Descriptive Checks:

- Calculate the mean and variance of your count data. If the variance is substantially larger than the mean, overdispersion is present [3].

- Examine the proportion of zeros in your data. If this proportion exceeds what is expected under a standard Poisson or Negative Binomial distribution, zero-inflation is likely [3].

Formal Model Comparison: Fit a Poisson model and a Negative Binomial model to the same data. The Negative Binomial model includes a dispersion parameter to handle variance greater than the mean. A significant improvement in model fit (e.g., a lower Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) or Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC)) for the Negative Binomial model indicates overdispersion [3]. Similarly, compare a standard Negative Binomial model to a Zero-Inflated Negative Binomial (ZINB) or Hurdle Negative Binomial (HUNB) model. A better fit for the zero-inflated or hurdle model confirms zero-inflation [3].

Table 1: Key Descriptive Statistics Indicating Overdispersion and Zero-Inflation

| Data Characteristic | Standard Model Expectation | Indicator of Problem | Common in Microbiome Data? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variance vs. Mean | Variance ≈ Mean (Equidispersion) | Variance >> Mean (Overdispersion) | Yes, very common [3] |

| Proportion of Zeros | Predicted by Poisson/NB distribution | Excess zeros beyond model expectation | Yes, very common [17] |

| Model Fit | Poisson model fits adequately | Negative Binomial model fits significantly better | Typical [3] |

Q3: What are the main statistical models for handling overdispersed and zero-inflated count data?

The primary models are the Negative Binomial (NB) model, Zero-Inflated Models (ZIP/ZINB), and Hurdle Models (HUP/HUNB). The table below summarizes their characteristics and applications.

Table 2: Comparison of Count Regression Models for Overdispersed and Zero-Inflated Data

| Model | Core Idea | Handles Overdispersion? | Handles Zero-Inflation? | Interpretation | Best for Microbiome Data When... |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative Binomial (NB) | Adds a dispersion parameter to Poisson; variance = μ + kμ² [3] | Yes | No | Single set of coefficients (Rate Ratios) [3] | Overdispersion is present without a need to model zero-inflation separately [18] |

| Zero-Inflated Negative Binomial (ZINB) | Mixture model: a logit model for "structural zeros" & an NB model for counts [3] | Yes | Yes | Two parts: 1) Logit for always-zero odds, 2) NB for count rates [3] | A subset of the population is not at risk for non-zero counts (e.g., sterile sites) [3] |

| Hurdle Negative Binomial (HUNB) | Two-part model: a logit for zero vs. non-zero & a truncated NB for positive counts [3] | Yes | Yes | Two parts: 1) Logit for presence/absence, 2) NB for abundance given presence [3] | The entire population is at risk, but factors influencing presence are different from abundance [3] |

Q4: When should I choose a Hurdle model over a Zero-Inflated model?

The choice is often guided by your biological hypothesis and the data-generating process.

Choose a Zero-Inflated (ZI) model if you believe zeros arise from two distinct processes: a "structural" one (e.g., a microbial taxon is genuinely absent from a specific niche) and a "sampling" one (e.g., the taxon is present but was not detected in the sample) [3]. ZI models are suitable when a sub-population is not at risk for non-zero counts.

Choose a Hurdle model if you believe all zeros are "structural" and the population is at risk for positive counts, but the probability of crossing from zero to a positive count is governed by one set of factors, while the magnitude of the positive count is governed by another [3]. This is intuitive for presence/absence and subsequent abundance modeling.

For microbiome data, where the exact process generating zeros is often unknown, it is recommended to fit both and compare model fit statistics like AIC or BIC, while also ensuring the chosen model aligns with biological plausibility [3].

Q5: What should I do if my predictors are highly correlated (multicollinearity) in addition to having overdispersed data?

Multicollinearity among predictors (e.g., correlated environmental variables or microbial taxa) can destabilize parameter estimates and inflate standard errors. To address this, regularized or penalized regression methods can be incorporated into your count models.

- Ridge Regression: This technique adds an L2 penalty term to the model's log-likelihood, which shrinks coefficients towards zero without eliminating them, stabilizing estimates in the presence of correlated predictors [19].

- Novel Hybrid Estimators: Recent research has developed specialized estimators for this purpose. For example, a new two-parameter hybrid estimator for Zero-Inflated Negative Binomial Regression Models combines the strengths of Ridge and Liu-type estimators to effectively mitigate multicollinearity [20]. Another advancement is the Ridge-Hurdle Negative Binomial model, which integrates Ridge regularization directly into the count component of a Hurdle model [19]. Simulation studies show these methods can achieve lower mean squared error (MSE) compared to standard models when multicollinearity is present [20] [19].

Q6: Do I always need a complex zero-inflated model for my microbiome data with many zeros?

Not necessarily. A standard Negative Binomial model can often provide an adequate fit, even when there are many zeros [18]. The Negative Binomial model is simpler to estimate and interpret. You can compare a standard NB model to a ZINB model using a likelihood ratio test (if the models are nested) or information criteria like AIC/BIC [18]. If the fit of the ZINB model is not significantly better, the standard NB model may be sufficient. The decision should also be based on theoretical grounds—whether it is biologically plausible that a sub-population has absolutely zero probability of a positive count [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Statistical "Reagents" for Analyzing Overdispersed Microbiome Data

| Tool / Method | Function | Key Application in Microbiome Research |

|---|---|---|

| Negative Binomial (NB) Regression | Models overdispersed count data by adding a dispersion parameter [3] | General workhorse for differential abundance analysis when variance > mean [3] |

| Zero-Inflated NB (ZINB) Model | Models data with excess zeros from two latent classes: "structural" and "sampling" zeros [3] | Identifying taxa that are genuinely absent vs. undetected; useful when a sub-population is not at risk [3] |

| Hurdle NB (HUNB) Model | Separately models the probability of a zero vs. a positive count and the distribution of positive counts [3] | Analyzing microbial presence/absence and, conditional on presence, its abundance [3] |

| Ridge Penalization (L2) | Shrinks coefficients of correlated predictors to stabilize estimates [19] | Handling multicollinearity in models (e.g., Ridge-ZINB, Ridge-Hurdle NB) [20] [19] |

| GLM-ASCA | Integrates Generalized Linear Models with ANOVA-simultaneous component analysis [21] | Multivariate analysis of microbiome data in complex experimental designs (e.g., with factors like time, treatment) [21] |

| Model Fit Statistics (AIC/BIC) | Compares model adequacy, penalizing for complexity [3] | Objective criteria for selecting between NB, ZINB, and HUNB models [3] |

| TT-10 | TT-10, CAS:2230640-94-3, MF:C11H10FN3OS2, MW:283.34 | Chemical Reagent |

| Ttc-352 | UNII-65ilh3Y0MI |

Experimental Protocol: A Workflow for Model Selection

The following diagram maps the logical workflow for diagnosing overdispersion and selecting an appropriate statistical model.

The Compositional Nature of Microbiome Data and Its Implications

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What does it mean that microbiome data is "compositional," and why is it a problem? Microbiome data generated by high-throughput sequencing is compositional because the total number of sequences obtained (library size) is arbitrary and fixed by the instrument. The data therefore carries only relative information, not absolute abundances. This means that an increase in the observed proportion of one microbe must be accompanied by a decrease in the observed proportions of others. Analyzing this data with standard statistical methods that assume independence between features can produce spurious correlations and misleading results [22]. The core issue is that the data resides in a simplex (all parts sum to a constant) rather than in a real Euclidean space, which violates the assumptions of many traditional statistical tests [23].

2. What are the main types of zeros in microbiome data, and why is distinguishing them important? Zeros in microbiome data are not all the same and can arise from different sources. Understanding these types is crucial for appropriate statistical handling [23]:

- Biological Zeros: The microorganism is genuinely absent from the sample at the time of collection.

- Technical Zeros (Non-biological): The microorganism is present but was not detected due to technical limitations like insufficient sequencing depth, sampling error, or PCR amplification bias [12] [24]. Ignoring these distinctions, or treating all zeros the same, can impair the performance of differential abundance tests and lead to false discoveries [23] [12].

3. How does compositionality lead to spurious correlations? Compositional data has a built-in negative correlation bias. Because all components must sum to one, an increase in one component forces the sum of all others to decrease. This creates a dependency that does not reflect true biological interactions. Furthermore, spurious correlations can appear or disappear when you subset the data, simply as an artifact of the compositional constraint. This problem was identified by Pearson over a century ago and is a critical consideration when constructing correlation networks from relative abundance data [22].

4. My data is from a longitudinal study. What additional compositional challenges should I consider? Longitudinal microbiome data adds a layer of complexity because compositions are measured at different time points, each with its own library size. These can be affected by distinct batch effects, and filtering may result in different sub-compositions at each time point. Analyzing such data requires methods that can account for both the compositional nature and the within-subject correlation across time. Ignoring this can distort the analysis of temporal trends and microbial dynamics [25] [26].

5. What is the recommended alternative to adding a pseudo-count (like +1) to handle zeros? While adding a pseudo-count is simple, it is an ad-hoc solution that can distort the data structure and is not generally recommended [23]. A more principled approach is to use log-ratio transformations, the foundation of Compositional Data Analysis (CoDA) [22] [26]. Common transformations include:

- Additive Log-ratio (ALR): Log-transforming the ratio of each taxon to a reference taxon.

- Centered Log-ratio (CLR): Log-transforming the ratio of each taxon to the geometric mean of all taxa in the sample.

These transformations map the data from the simplex to a real Euclidean space, allowing for the use of standard statistical methods. Specialized tools like

coda4microbiomeand ANCOM implement these approaches for robust analysis [23] [26].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Inflated False Discoveries in Differential Abundance Analysis

Symptoms: Your differential abundance analysis identifies a long list of significant taxa, but the results are biologically implausible or fail to validate in follow-up experiments.

Diagnosis: This is a classic symptom of ignoring compositionality and zero-inflation. Standard tests applied to raw counts or relative abundances often mistake compositional effects for true biological signal [22] [24].

Solution:

Adopt a compositional data analysis (CoDA) framework. The following workflow, implemented in tools like coda4microbiome, is designed for this purpose [26]:

Detailed Protocol:

- Input Data: Begin with your filtered OTU or ASV count table.

- Handle Zeros: Use model-based approaches (e.g., zero-inflated models) or identify types of zeros instead of universally adding a pseudo-count [23] [12].

- Log-Ratio Transformation: Apply a centered log-ratio (CLR) transformation. For each taxon j in sample i, calculate:

CLR(X_ij) = log[ X_ij / G(X_i) ], whereG(X_i)is the geometric mean of all taxa in sample i [23] [26]. - Model Fitting: Use a penalized regression model (like elastic-net) on the matrix of all possible pairwise log-ratios. This helps in managing high dimensionality [26].

- Signature Identification: The model selection process will identify a minimal set of taxa with maximum predictive power. The result is often expressed as a balance—a weighted log-ratio between a group of taxa that are positively associated with the outcome and a group that are negatively associated [26].

- Validation: Always validate the predictive power of the identified microbial signature using cross-validation or an independent dataset.

Problem 2: Managing Group-wise Structured Zeros in Case-Control Studies

Symptoms: A taxon appears to be highly abundant in one group (e.g., healthy controls) but is completely absent (all zeros) in the other group (e.g., disease cases). Standard differential abundance tools either fail to detect this taxon or provide unstable results.

Diagnosis: This is the problem of group-wise structured zeros or perfect separation. Many models struggle with this as it can lead to infinite parameter estimates [12].

Solution: A combined testing strategy that distinguishes between taxa with group-wise zeros and those without.

Experimental Protocol:

- Pre-processing: Filter out low-prevalence taxa as a first step to reduce noise [12] [24].

- Structured Zero Identification: Partition your taxa into two sets:

- Set A (Structured Zeros): Taxa with all zeros in one group and non-zero counts in the other.

- Set B (Standard Taxa): All other taxa.

- Differential Testing:

- For Set A, the presence/absence pattern is itself a powerful biological signal. These taxa can be reported as differentially abundant based on a test of proportions (e.g., Fisher's exact test) [12].

- For Set B, apply a robust differential abundance method capable of handling zero-inflation and compositionality. The DESeq2-ZINBWaVE pipeline is a recommended choice, as it uses observation weights from a zero-inflated negative binomial model to improve power and control false discovery rates [12].

- Result Integration: Combine the significant taxa from Set A and Set B for a complete list of candidates. Always confirm findings with biological context.

Problem 3: Correcting for Batch Effects in Compositional Data

Symptoms: In a meta-analysis of multiple datasets, samples cluster strongly by batch (e.g., sequencing run, lab) rather than by the biological factor of interest.

Diagnosis: Both technical batch effects and the inherent compositionality of the data are confounding your analysis. Standard batch effect correction tools often assume a Gaussian distribution and perform poorly on sparse, over-dispersed count data [27].

Solution: Use a two-pronged approach to correct for systematic and non-systematic batch effects.

Detailed Methodology:

- Systematic Batch Effect Correction:

- Use a negative binomial regression model tailored for count data [27].

- Model the count of each OTU as a function of the batch ID (as a fixed effect) and relevant biological covariates.

- The model equation is:

log(μ_ijg) = σ_j + X_iβ_j + γ_jg + log(N_i), whereγ_jgis the mean batch effect for OTU j in batch g. - Obtain batch-corrected counts by subtracting the estimated batch effect:

log(μ_ij*) = log(μ_ijg) - γ_jg[27].

- Non-systematic Batch Effect Correction:

- For residual, sample-specific batch influences, apply composite quantile regression [27].

- This method adjusts the distribution of OTUs in each batch to match a reference batch (selected based on a test like Kruskal-Wallis), accounting for variability at the individual OTU level without assuming a specific data distribution.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Key Software Tools for Analyzing Compositional Microbiome Data

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Feature | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| coda4microbiome (R package) | Microbial signature identification in cross-sectional & longitudinal studies. | Uses penalized regression on pairwise log-ratios; results expressed as interpretable balances. | [26] |

| ANCOM/ANCOM-BC | Differential abundance testing. | Robustly controls FDR by testing the null hypothesis that a taxon is not differentially abundant relative to most other taxa. | [23] [26] |

| ALDEx2 | Differential abundance analysis. | Uses a centered log-ratio transformation and Dirichlet-multinomial model to account for compositionality. | [26] |

| DESeq2-ZINBWaVE | Differential abundance testing in zero-inflated data. | Integrates ZINBWaVE-generated observation weights into DESeq2 to handle zero-inflation. | [12] |

| MMUPHin | Batch effect correction and meta-analysis. | Provides a unified pipeline for normalizing and correcting batch effects across multiple microbiome studies. | [27] |

Visualizing Analysis Workflows and Data Relationships

Microbiome Data Analysis Pathway

Comparative Analysis of Normalization and Transformation Methods

Table 2: Comparison of Common Methods to Address Compositionality and Sparsity

| Method | Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Suitability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rarefaction | Subsampling to even sequencing depth. | Simple; reduces library size bias. | Discards data; can introduce its own biases; not a solution for compositionality. | [22] |

| Pseudo-Count (+1) | Adding a small constant to all counts. | Simple; enables log-transformation. | Ad-hoc; can distort relationships and create false signals, especially for low-abundance taxa. | [23] |

| Centered Log-Ratio (CLR) | Log-transform ratios to geometric mean. | Symmetric treatment of taxa; standard PCA can be used. | Geometric mean is zero if any taxon is zero (requires zero-handling). | [22] [26] |

| Additive Log-Ratio (ALR) | Log-transform ratios to a reference taxon. | Simple; reduces dimensionality. | Results depend on choice of reference taxon (must be present in all samples). | [23] |

| Geometric Mean of Pairwise Ratios (GMPR) | Size factor calculation based on pairwise ratios. | Robust normalization for zero-inflated data. | A normalization method, not a full compositional transformation. | [24] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the fundamental difference between 16S rRNA and shotgun metagenomic sequencing? 16S rRNA gene sequencing is a targeted approach that uses PCR to amplify and sequence specific hypervariable regions of the bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA gene, which serves as a phylogenetic marker. This method is primarily used for taxonomic identification and profiling of bacterial and archaeal communities [28] [29]. In contrast, shotgun metagenomic sequencing sequences all genomic DNA present in a sample without targeting specific genes. This provides a comprehensive view of all microorganisms (including bacteria, viruses, fungi, and archaea) and enables functional gene analysis [29] [30].

2. Which sequencing method provides higher taxonomic resolution? Shotgun metagenomics generally provides higher taxonomic resolution, potentially down to the species or even strain level, because it accesses the entire genetic content [29] [30]. While 16S rRNA sequencing typically resolves to the genus level, advances in error-correction algorithms (like DADA2) have improved its accuracy and now allow for species-level resolution for many organisms [29]. However, the actual resolution of both methods can be limited by the completeness and quality of their respective reference databases [29] [31].

3. How does the choice of sequencing method impact the detection of functional potential? Shotgun metagenomics is the direct method for assessing the functional potential of a microbial community, as it can identify genes involved in specific metabolic pathways, virulence, and antibiotic resistance [29] [32]. While 16S rRNA data alone cannot directly provide functional information, computational tools like PICRUSt can infer metabolic function from taxonomy data, though this is predictive and indirect [29].

4. What are the primary data characteristics that challenge the statistical analysis of microbiome data? Data from both 16S and shotgun sequencing are characterized by:

- Compositionality: The data conveys relative, not absolute, abundance. An increase in one taxon's reads necessarily causes a decrease in the observed reads for others [28] [32].

- Sparsity and Zero-Inflation: A large percentage (often 80-95%) of the data are zeros, arising from both true biological absence and technical limitations (e.g., low sequencing depth) [11] [12].

- Overdispersion: The variance in the data is much higher than the mean [32] [33].

- High Dimensionality: The number of features (taxa or genes) is much greater than the number of samples, leading to the "large P, small N" problem [11] [32].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Handling Zero-Inflation and Overdispersion in Differential Abundance Analysis

Problem: Standard statistical models fail or produce false positives because the count data has an excess of zeros and high variance.

Solution: Employ models and workflows specifically designed for these characteristics.

Recommended Workflow: A combined approach can address different types of zeros.

- For general zero-inflation, use a method that incorporates observation weights, such as DESeq2-ZINBWaVE. This method helps control the false discovery rate in the presence of technical zeros [12].

- For "group-wise structured zeros" (where a taxon is absent in all samples of one group but present in another), use the standard DESeq2 with its built-in penalized likelihood estimation, which provides finite parameter estimates and stable p-values for such taxa [12].

Alternative Models: Several other models are available to handle these issues.

- Zero-Inflated Gaussian Mixed Models (ZIGMMs): A flexible model for analyzing longitudinal microbiome data (both proportions and counts) that accounts for zero-inflation, within-subject correlations, and various random effects [33].

- Zero-Inflated Negative Binomial Models (ZINB): Useful for modeling overdispersed count data with excess zeros [12].

- corncob: A count regression model that uses a beta-binomial distribution to account for overdispersion and compositionality [32].

Issue 2: Addressing the Compositional Nature of Data

Problem: Apparent correlations and differential abundance between taxa can be spurious, arising from the closed nature of the data (i.e., all counts sum to the library size).

Solution: Use compositionally aware methods or appropriate normalizations.

Compositional Data Analysis (CoDA) Methods: These methods analyze data based on log-ratios between components, which is the relevant information in compositional data [28].

Normalization Strategies: For count-based models (e.g., DESeq2, edgeR), choose normalizations that mitigate compositional effects.

Issue 3: Choosing an Appropriate Sequencing Method for a Specific Study Goal

Problem: Uncertainty about whether to use 16S rRNA or shotgun metagenomic sequencing, leading to inadequate data for the research objectives.

Solution: Systematically evaluate the project's goals, budget, and sample type. The following table and decision guide provide a structured comparison.

- Technology Comparison Table

| Feature | 16S rRNA Sequencing | Shotgun Metagenomics |

|---|---|---|

| Target | 16S rRNA gene hypervariable regions [29] | All genomic DNA in sample [29] |

| Taxonomic Resolution | Genus to species (with modern tools) [29] | Species to strain-level [29] [30] |

| Functional Profiling | Indirect inference only (e.g., PICRUSt) [29] | Direct assessment of genes and pathways [29] [32] |

| Cross-Domain Coverage | Bacteria & Archaea (Fungi via ITS) [29] | Bacteria, Archaea, Viruses, Fungi [29] [31] |

| Sensitivity to Host DNA | Low (due to targeted PCR) [29] | High (requires depletion kits for host-heavy samples) [29] |

| DNA Input Requirement | Low (as low as 10 gene copies) [29] | Higher (minimum of 1 ng) [29] |

| Recommended Sample Type | All, including low-biomass [29] | Human microbiome (e.g., feces, saliva) [29] |

| Cost per Sample | ~$80 [29] | ~$200 (Full), ~$120 (Shallow) [29] |

| Data Sparsity | High [32] [31] | Very High [32] |

| Key Limitation | Primer bias, limited resolution [34] [29] | Database dependency, host DNA interference, cost [29] [31] |

- Experimental Protocol & Decision Guide

Diagram: A decision workflow for choosing between 16S rRNA and shotgun metagenomic sequencing.

Issue 4: Managing Database-Related Biases and False Positives

Problem: Shotgun sequencing yields false positive taxonomic calls, or 16S sequencing fails to classify a significant portion of sequences.

Solution: Understand and mitigate database limitations.

For Shotgun Metagenomics:

- Problem: If a microbe in the sample does not have a closely related representative in the reference genome database, it may be missed entirely or misassigned to a "closely-related" genome, creating false positives [29].

- Action: Use the most comprehensive database available (e.g., curated databases for human gut studies like UHGG). For non-model environments, consider manually adding genomes of interest to the database if they are known [29] [31].

For 16S rRNA Sequencing:

- Problem: Primer choice can introduce bias, as no single hypervariable region can distinguish all bacterial species [34] [31].

- Action: Use well-established primer sets (e.g., targeting the V3-V4 regions) and consider using multi-step taxonomic classification pipelines (e.g., combining DADA2 with BLASTN and Kraken2 against SILVA and RefSeq databases) to increase the percentage of sequences classified to the species level [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| NucleoSpin Soil Kit | DNA extraction from complex samples like soil and feces [31]. | Used in shotgun metagenomic protocols for human stool samples [31]. |

| DNeasy PowerLyzer PowerSoil Kit | DNA extraction with bead-beating for efficient lysis of microbial cells [31]. | Used in 16S rRNA sequencing protocols to minimize bias and maximize yield [31]. |

| UMD-SelectNA CE-IVD Kit | Semi-automated method for 16S rRNA PCR and Sanger sequencing. Includes human DNA depletion and DNase treatment steps [34]. | For targeted 16S Sanger sequencing in clinical diagnostics [34]. |

| Nextera XT DNA Library Prep Kit | Prepares sequencing libraries from DNA samples for Illumina platforms [34]. | Used in shotgun metagenomics library preparation [34]. |

| HostZERO Microbial DNA Kit | Depletes host DNA (e.g., human) from samples to increase microbial sequencing depth [29]. | Critical for shotgun sequencing of samples with high host DNA content (e.g., tissue, blood) [29]. |

| ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standard | Defined mock microbial community with known composition. | Serves as a positive control for evaluating sequencing accuracy, pipeline performance, and false positive rates [29]. |

| Velufenacin | Velufenacin, CAS:1648737-78-3, MF:C19H20ClFN2O2, MW:362.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| VM4-037 | VM4-037 CAIX PET Tracer | VM4-037 is a small molecule CA-IX targeting PET imaging agent for research on renal cell carcinoma and tumor hypoxia. For Research Use Only. Not for human diagnostics. |

The Statistical Toolkit: Models for Analyzing Complex Microbiome Data

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Data Import and Phyloseq Objects

Q1: I tried reading my BIOM file using phyloseq, but it didn't work. What's wrong?

The most common cause is a mismatch between the BIOM file format version and the package's expected format. The original phyloseq support was for BIOM-format version 1 (JSON-based). However, many recent QIIME outputs now default to version 2 (HDF5-based). The solution is to ensure you are using the import_biom function from a recent phyloseq version that supports both formats via the biomformat package [35].

Q2: My phyloseq object seems broken or is causing errors in functions. How can I check it?

Common issues include missing sample data, missing taxonomy tables, or taxa that sum to zero across all samples. You can systematically check and fix your phyloseq object using the following approach [36]:

Table: Common Phyloseq Object Issues and Solutions

| Issue | Symptoms | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| NULL sample_data | Functions requiring sample variables fail | Create a sampledata dataframe with samplenames |

| NULL tax_table | Taxonomy-based operations fail | Create a 1-column taxtable matrix with taxanames |

| Zero-sum taxa | Warnings about taxa removal; statistical issues | Remove undetected taxa with phyloseq_validate(remove_undetected = TRUE) |

| VU0453379 | VU0453379, MF:C26H34N4O2, MW:434.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| VU0463271 | VU0463271, MF:C19H18N4OS2, MW:382.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Normalization and Data Preprocessing

Q3: Why is normalization critical for microbiome data analysis, and what methods are available?

Microbiome data have unique characteristics including compositionality, sparsity (zero-inflation), and over-dispersion that necessitate normalization before statistical analysis. Normalization mitigates artifactual biases from variations in sample collection, library preparation, and sequencing depth [11].

Table: Categories of Normalization Methods for Microbiome Data

| Category | Examples | Best For |

|---|---|---|

| Ecology-based | Rarefying | Even sampling depth comparison |

| Traditional | Total Sum Scaling, TSS | Simple proportional data |

| RNA-seq-based | DESeq2's median-of-ratios, edgeR's TMM | Differential abundance analysis |

| Microbiome-specific | CSS, Wrench, Geometric Mean of Pairwise Ratios | Addressing compositionality and zeros |

Rarefying (subsampling to even depth) remains common but has limitations. Methods adopted from RNA-seq analysis like DESeq2's median-of-ratios are widely used for differential abundance analysis, while newer compositionally-aware methods are valuable for specific data structures [11].

Differential Abundance Analysis

Q4: How do I handle excessive zeros in my OTU table when using DESeq2?

The DESeq2 package expects count data and can error with sparse OTU tables. A recommended solution is to calculate geometric means of counts and use these for size factor estimation [37]:

This approach addresses the problem of many zeros causing errors in the default size factor estimation, which relies on a geometric mean that becomes zero when any count is zero [37].

Q5: What's the best approach for differential abundance analysis when dealing with both zero-inflation and group-wise structured zeros?

A combined approach using different methods strategically can address these challenges effectively. For complex zero scenarios [12]:

- DESeq2-ZINBWaVE: Use for general zero-inflation (weights-based approach to control false discovery rate)

- Standard DESeq2: Apply for taxa with group-wise structured zeros (perfect separation) due to its penalized likelihood framework

This combined pipeline ensures proper handling of both biological zeros (true absences) and technical zeros (undersampling artifacts) that are common in microbiome datasets [12].

Batch Effect Correction

Q6: How can I correct for batch effects in microbiome data given its unique characteristics?

Batch effects from technical variations require specialized approaches. A composite quantile regression approach combined with negative binomial regression addresses both systematic batch effects (consistent across samples) and non-systematic batch effects (varying by OTU composition) [27]:

This approach uses negative binomial regression to address consistent batch influences and composite quantile regression to adjust OTU distributions relative to a reference batch, accommodating microbiome data's high zero-inflation and over-dispersion [27].

Troubleshooting Guides

DESeq2 with Phyloseq: Common Errors and Solutions

Problem: DESeq2 fails with "every gene contains at least one zero" error

This occurs with sparse OTU tables common in microbiome data [37].

Solution Steps:

- Calculate geometric means using only positive counts

- Apply these geometric means to estimate size factors

- Proceed with DESeq2 analysis

Problem: Non-uniform p-value distributions in DESeq2 results

This indicates potential issues with dispersion estimation or model fit, which is common with small sample sizes typical in microbiome studies [38].

Solution Approaches:

- Increase biological replicates when possible

- Consider the

fitType = "local"parameter for complex datasets - Explore alternative methods like QuasiSeq for larger sample sizes (n ≥ 4) [38]

Phyloseq Object Validation and Repair

Problem: Functions fail due to incomplete phyloseq objects

Diagnosis and Repair Workflow:

This systematic validation ensures all phyloseq components are present and appropriate for analysis [36].

Experimental Protocols

Differential Abundance Analysis with DESeq2

Protocol: Comprehensive DESeq2 workflow for microbiome data [39] [12]

Materials and Reagents:

- Normalized OTU/ASV table (from QIIME2, DADA2, or similar)

- Sample metadata with experimental design

- R with phyloseq and DESeq2 packages installed

Procedure:

- Data Import and Preprocessing

- Import OTU table and sample metadata into phyloseq

- Remove samples with extremely low sequencing depth

- Filter out taxa with prevalence below 1-5% across samples

Phyloseq to DESeq2 Conversion

Sparse Data Handling (if needed)

Statistical Testing

Results Extraction and Interpretation

Troubleshooting:

- For convergence issues: Try

fitType = "local"orfitType = "mean" - For small sample sizes: Consider

test = "LRT"with reduced model - For multiple groups: Use contrasts for specific comparisons

Batch Effect Correction Protocol

Protocol: Addressing technical variability in multi-batch studies [27]

Materials:

- Multi-batch microbiome dataset

- Batch identification metadata

- Reference batch selection criteria

Procedure:

- Batch Effect Diagnosis

- Perform PCoA with batch coloring

- Calculate PERMANOVA R-squared values for batch effect

- Compute Average Silhouette Coefficients

Systematic Batch Effect Correction

Non-systematic Batch Effect Correction

- Apply composite quantile regression

- Adjust OTU distributions to reference batch

- Validate using Kruskal-Wallis test

Correction Validation

- Compare pre- and post-correction PCoA plots

- Verify biological signal preservation

- Confirm batch effect reduction via PERMANOVA

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools for Microbiome Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| phyloseq R package | Data integration and visualization | Unified analysis of OTU tables, sample data, taxonomy, and trees |

| DESeq2 | Differential abundance testing | Count-based analysis with negative binomial models |

| biomformat | BIOM file import | Handling both JSON and HDF5 BIOM format versions |

| ZINBWaVE | Zero-inflated negative binomial modeling | Weighting for improved FDR control in sparse data |

| MMUPHin | Batch effect correction | Addressing heterogeneity in meta-analysis |

| microViz | Phyloseq validation and extension | Diagnostic functions and visualization enhancements |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the fundamental differences between ZINB, ZIBB, and ZIGDM models?

These models are designed to handle count data with excess zeros, but they use different underlying distributions and are suited for different data structures.

- ZINB (Zero-Inflated Negative Binomial): This is a mixture model that combines a point mass at zero with a Negative Binomial (NB) count distribution. It is a general-purpose model for overdispersed count data where the variance exceeds the mean [40] [41]. It is widely used in genomics and microbiome analysis [42] [43].

- ZIBB (Zero-Inflated Beta-Binomial): This model is specifically designed for compositional data or data arising from a binomial process where the counts are overdispersed relative to binomial variance. It is appropriate when your counts represent the number of successes out of a fixed number of trials (e.g., counts of a specific taxon out of a total read count) and exhibit extra zeros [44].

- ZIGDM (Zero-Inflated Generalized Dirichlet-Multinomial): This model extends the framework to multivariate count data that is compositional and correlated. It accounts for the fact that the abundances of different features (e.g., microbial taxa) are not independent and sum to a constant total (library size) [32] [44].

2. How do I choose the right model for my microbiome dataset?

The choice depends on the nature of your data and the research question. The following table summarizes key selection criteria.

Table 1: Model Selection Guide for Zero-Inflated Count Data

| Model | Primary Use Case | Key Data Characteristics | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZINB | General overdispersed count data [40] [43] | - Univariate counts- Overdispersion (variance > mean)- Excess zeros | Handles overdispersion well; widely implemented and understood [41]. |

| ZIBB | Binomial/proportion data with zeros [44] | - Counts with a fixed total (e.g., 16S rRNA sequence counts)- Overdispersion beyond binomial variance- Excess zeros | Specifically models the binomial nature of sequencing data. |

| ZIGDM | Multivariate, compositional count data [32] [44] | - Multiple, correlated count responses- Compositional data (relative abundances)- Complex correlation structure between features | Captures dependencies between features; ideal for joint modeling of microbial taxa. |

A general workflow for model selection and diagnostic checks can be visualized as follows:

3. What are the common convergence issues and how can I troubleshoot them?

Model fitting, especially for complex mixtures like ZIGDM, can fail due to several reasons:

- Cause 1: Insufficient Sample Size. Complex models with many parameters require a large number of observations. With small sample sizes, the algorithm may not have enough information to converge.

- Solution: Increase sample size if possible. If not, consider a simpler model (e.g., ZINB instead of ZIGDM) or use strong regularization [40].

- Cause 2: Incorrect Model Specification. Using a ZINB or ZIGDM model on data that is not overdispersed can lead to convergence problems. Studies have shown that NB and ZINB models face substantial convergence issues when modeling equidispersed data [40].

- Solution: Always test for overdispersion before applying these models. Use a likelihood ratio test to compare a Poisson model to a negative binomial model [41].

- Cause 3: Poorly Scaled Predictors. Variables with vastly different scales (e.g., age and gene expression counts) can make the optimization landscape difficult to traverse.

- Solution: Center and scale your continuous covariates before fitting the model.

4. How should I handle the compositional nature of microbiome data in these models?

Microbiome sequencing data is inherently compositional because the total number of reads per sample (library size) is arbitrary and does not reflect absolute abundance [32] [15] [44].

- Standard Practice: Include the log of the total sequence reads (

log(T_i)) as an offset term in your model. This is a standard approach in methods likeedgeRandDESeq2and is directly implemented in negative binomial mixed models (NBMMs) [43]. The model formula looks like:log(μ_i) = log(T_i) + X_iβ + ... - Advanced Approach: Use models specifically designed for compositionality, such as ZIGDM or the BMDD (BiModal Dirichlet Distribution) framework for zero imputation, which explicitly model the multivariate correlation structure and the sum-to-one constraint [44] [45].

5. What diagnostic checks should I perform after fitting a model?

- Check for Residual Overdispersion: Even after fitting a ZINB model, check residuals to ensure overdispersion is adequately captured.

- Zero-Inflation Test: Use tests like the Vuong test to compare your zero-inflated model (e.g., ZINB) against a standard count model (e.g., NB). A significant p-value favors the zero-inflated model [41].

- Goodness-of-Fit: Compare models using information criteria like AIC (Akaike Information Criterion) or BIC (Bayesian Information Criterion). A lower value indicates a better fit, balancing model complexity and goodness-of-fit [40] [41].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fitting a ZINB Model for Differential Abundance Analysis

This protocol outlines the steps to identify taxa whose abundances are associated with a specific host factor (e.g., disease status, diet) using a ZINB model.

1. Data Preprocessing and Normalization:

- Input: Raw OTU/ASV count table, sample metadata.

- Normalization: Account for varying sequencing depths. While the offset method is common, other popular methods include Cumulative Sum Scaling (CSS) [32] or methods from

DESeq2/edgeRlike Relative Log Expression (RLE) or Trimmed Mean of M-values (TMM) [32] [44].

2. Model Fitting:

- For each taxon, fit a ZINB model. The model has two parts:

- Count Component:

log(μ_i) = log(T_i) + β_0 + β_1*X_i + ...whereX_iis the host factor of interest. - Zero-Inflation Component:

logit(π_i) = γ_0 + γ_1*Z_i + ...whereπ_iis the probability of an excess zero. The predictorsZ_ican be the same as or different fromX_i.

- Count Component:

3. Parameter Estimation:

- Parameters are typically estimated via Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE). For complex models or Bayesian approaches (like BAMZINB [46]), variational approximation or Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods may be used [45] [46].

4. Inference and Interpretation:

- Test the null hypothesis that the coefficient for your host factor is zero (H₀: β₠= 0). A significant β₠indicates a change in the abundance of the taxon is associated with the host factor, conditional on the taxon being present.

- The zero-inflation component's coefficients (γ) help understand which factors drive the excess zeros.

Protocol 2: Implementing a Multivariate Analysis with ZIGDM

This protocol is for when you need to model multiple taxa simultaneously, accounting for the correlations between them.

1. Data Preparation:

- Input: A high-dimensional count table of taxa (e.g., at the genus level).

- Address Compositionality: The model inherently accounts for the compositional structure through the Dirichlet-Multinomial framework [44].

2. Model Specification:

- The ZIGDM model jointly models the multivariate count response. It incorporates:

3. Estimation:

- Fitting a full ZIGDM model is computationally intensive. Estimation often involves variational inference or Bayesian methods with carefully chosen priors to ensure stability and convergence [45] [46].

4. Output:

- The model provides estimates of the association between covariates and each taxon, while implicitly accounting for the presence and correlations of all other taxa in the model.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools for Analyzing Zero-Inflated Microbiome Data

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| R Statistical Software | Primary programming environment for statistical computing and graphics. | Core platform for implementing all statistical analyses [42] [32] [43]. |

ZINB Model (e.g., in pscl or glmmTMB) |

Fits Zero-Inflated Negative Binomial regression models. | Workhorse model for univariate, overdispersed count data with excess zeros [40] [41]. |

| ZIGDM / Corncob R Package | Fits models for analyzing microbiome data based on a beta-binomial or related framework, accounting for library size and compositionality. | Differential abundance analysis for individual taxa, modeling variability and compositionality [32] [44]. |

| Vuong Test | A statistical test to compare non-nested models (e.g., ZINB vs. NB). | Model diagnosis and selection to confirm that a zero-inflated model is necessary [41]. |

| DESeq2 / edgeR | Bioconductor packages for differential analysis of sequence count data. | Standard methods for RNA-Seq data that can be applied to microbiome data; use negative binomial models without zero-inflation [32]. |

| BMDD Framework | A Bayesian method for zero imputation using a BiModal Dirichlet Distribution prior. | Accurately imputing zeros in microbiome data to improve downstream analyses like differential abundance [45]. |

| American Gut Project (AGP) Data | A large public dataset of microbiome samples with extensive host metadata. | A key resource for developing and testing new statistical methods like NB factor regression [42]. |

Hurdle models are a class of statistical models specifically designed to handle data with an excess of zero values. In these models, a random variable is modeled using two distinct parts: the first part models the probability of attaining a zero value, while the second part models the probability of all non-zero values [47]. This framework is particularly valuable in microbiome research, where data frequently exhibit zero-inflation alongside other challenging characteristics like over-dispersion and compositional effects [17] [48]. The use of hurdle models is motivated by the need to account for zero counts that are not sufficiently explained by standard statistical distributions, providing a more accurate and nuanced representation of the underlying biological processes [47].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the fundamental difference between a Hurdle Model and a Zero-Inflated Model? Both models handle excess zeros, but they conceptualize the zero values differently. A hurdle model is a two-component mixture where one component models whether the count is zero or not (using a Bernoulli distribution), and the second component models the positive counts using a truncated count distribution (e.g., Poisson or Negative Binomial). In contrast, a zero-inflated model assumes that zeros come from two distinct sources: a point mass that always generates zeros (the "structural" zeros) and the standard count distribution (e.g., Poisson) which can also generate zeros (the "sampling" zeros) [47] [49]. The hurdle model treats all zeros as originating from a single process.

2. When should I use a Hurdle Model for my microbiome data? You should consider a hurdle model when your microbiome count data (e.g, Operational Taxonomic Unit or OTU counts) exhibits a large proportion of zeros that a standard Poisson or Negative Binomial model cannot adequately fit. This is often the case when the data generation process has a "hurdle" that must be overcome for a non-zero count to be observed, such as a taxon being either present and detected or entirely absent [47] [50]. If your goal is to cluster microbiome features based on their presence/absence and abundance patterns, a Poisson Hurdle Model is particularly suitable [50].

3. Can Hurdle Models handle over-dispersed data? Yes. While the basic hurdle model can use a Poisson distribution for the count component, a Negative Binomial Hurdle Model is specifically designed to handle over-dispersion (variance greater than the mean) in the non-zero counts [51]. This is a common feature of microbiome data, making the Negative Binomial version a frequently chosen tool.

4. How do I implement a basic Hurdle Model in statistical software? The hurdle model likelihood can be implemented directly in statistical programming environments. The model can be formulated such that if the count ( yn ) is zero, it contributes ( \log(\theta) ) to the log likelihood. If ( yn ) is positive, it contributes ( \log(1-\theta) + \log(\textsf{Poisson}(y_n \mid \lambda)) - \log(1 - \textsf{PoissonCDF}(0 \mid \lambda)) ) [49]. Several R packages, such as

pscl, offer built-in functions for fitting hurdle models.5. What are the key assumptions of a Hurdle Model? The primary assumption is that all zeros are generated by a single process, modeled by the binary component. The non-zero counts are assumed to be generated from a truncated count distribution, which applies only to positive integers. The model also assumes that the two processes (generating zeros and generating positive counts) are independent [47] [49].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Symptom | Diagnostic Check | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Non-Convergence | Optimization algorithms fail to converge; parameter estimates are unstable. | Check software warnings; examine traceplots of parameters during fitting. | Simplify the model (e.g., reduce covariates), use different starting values for parameters, or use a more robust optimizer. |

| Poor Model Fit | Significant residuals; the model does not capture the patterns in the observed data, especially the number of zeros or the distribution of counts. | Perform posterior predictive checks or use goodness-of-fit tests like the rootogram. | Consider a different distribution for the count component (e.g., Negative Binomial instead of Poisson) or explore a zero-inflated model as an alternative. |

| Uncertainty in Number of Clusters | In cluster analysis, the number of groups with similar microbial features is unclear. | Use the Modified Expected Strength (MES) criterion or the Integrated Complete Likelihood (ICL) criterion. | Employ a clustering algorithm that includes a method for selecting the number of clusters, such as the Poisson Hurdle Model-based method which uses MES [50]. |

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Applying a Negative Binomial Hurdle Model to Microbiome Data

This protocol is adapted from methods used for batch effect correction and is applicable for modeling microbiome counts directly [27].

Objective: To model an OTU count table, accounting for excess zeros and over-dispersion.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Let ( Y{ijg} ) represent the count for the ( j )-th OTU in the ( i )-th sample from the ( g )-th batch. Construct a covariate matrix ( Xi ) that includes biological and technical factors (e.g., disease status, age, library size).

- Model the Non-Zero Counts: Model the positive counts (( Y{ijg} \mid Y{ijg} > 0 )) using a Negative Binomial (NB) regression.

- The model is: ( \log(\mu{ijg}) = \sigmaj + Xi \betaj + \gamma{jg} + \log(Ni) ) [27].

- Here, ( \mu{ijg} ) is the expected count, ( \sigmaj ) is the OTU-specific baseline, ( \betaj ) are covariate coefficients, ( \gamma{jg} ) is the batch effect, and ( \log(N_i) ) is the offset for library size.

- The NB variance is ( \text{Var}(Y{ijg} \mid Y{ijg}>0) = \mu{ijg} + \theta{jg} \mu{ijg}^2 ), where ( \theta{jg} ) is the dispersion parameter.

- Model the Zero Hurdle: Simultaneously, model the probability of a zero value, typically using a logistic regression (Bernoulli model) with the same or a subset of the covariates.

- Parameter Estimation: Estimate the parameters (e.g., ( \betaj ), ( \theta{jg} ), and the hurdle parameters) using maximum likelihood or Bayesian methods.

- Inference: Draw conclusions based on the combined model. For example, to adjust for a batch effect, you would subtract the estimated ( \gamma{jg} ) from the linear predictor: ( \log(\mu{ij}^*) = \log(\mu{ijg}) - \gamma{jg} ) [27].

Protocol: Clustering Microbiome Features using a Poisson Hurdle Model

This protocol is used to group OTUs that behave similarly across samples [50].

Objective: To identify clusters of microbial taxa with similar presence/absence and abundance patterns.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Preprocessing: Organize the data into an ( n \times m ) matrix of counts, where ( n ) is the number of samples and ( m ) is the number of OTUs.

- Model-Based Clustering: Apply a model-based clustering method where the data likelihood is given by a Poisson Hurdle Model.

- Algorithm Fitting: Use the Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm, or a modified version employing simulated annealing, to fit the model and assign OTUs to clusters.

- Cluster Number Selection: Utilize the algorithm's built-in methods, such as the Modified Expected Strength (MES) criterion, to determine the optimal number of clusters.

- Validation: Validate the clustering results using internal validation metrics and, if possible, biological interpretation.

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Hurdle Model Analysis Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Tools for Hurdle Model Analysis in Microbiome Research

| Item | Function in Analysis | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| R Statistical Software | Primary environment for data manipulation, model fitting, and visualization. | The base R environment provides the necessary foundation for coding and package management. |

pscl R Package |

Provides functions for fitting hurdle (and zero-inflated) models for cross-sectional data. | A key tool for implementing standard hurdle models [51]. |

PHclust R Package |

A specialized package for performing model-based clustering of sparse count data using Poisson Hurdle Models. | Implements the protocol for clustering microbiome features [50]. |

Stan / rstan |

A probabilistic programming language for statistical inference. Useful for fitting complex Bayesian hurdle models. | Allows for custom model specification and robust uncertainty quantification [49]. |

| Negative Binomial Regression | The statistical foundation for modeling the over-dispersed, non-zero count component of the data. | Used to handle variance that exceeds the mean in positive counts [27] [51]. |

| EM Algorithm | A computational algorithm used for parameter estimation in models with latent variables, such as in clustering. | Central to the fitting procedure of the PHclust method [50]. |

Beta-Binomial and Dirichlet-Multinomial Models for Overdispersion

Frequently Asked Questions

1. My microbiome count data has many zeros. Will standard Beta-Binomial or Dirichlet-Multinomial (DM) models suffice? Standard Beta-Binomial (for a single taxon) or DM (for multiple taxa) models often cannot fully capture the high number of zeros in microbiome data. The excess zeros can be both structural (the taxon is truly absent) and at-risk (the taxon is present but unobserved), requiring specialized zero-inflated versions of these models for accurate analysis [52] [53].

2. What is the key difference between Zero-Inflated Beta-Binomial (ZIBB) and Zero-Inflated Dirichlet-Multinomial (ZIDM) models? The key difference is the scope of analysis. ZIBB is typically used for univariate analysis, testing one taxon at a time for association with phenotypes or covariates [54]. ZIDM is a multivariate model that analyzes all taxa simultaneously, which naturally accounts for the compositional nature of microbiome data and the correlations between taxa [52] [55] [53].

3. When fitting a ZIDM model, my model fitting is slow and the results are hard to interpret. What should I check? This is a common challenge. First, ensure that the model is correctly specified and that you are using an efficient inference algorithm. Some Bayesian implementations of ZIDM can be computationally intensive [55]. Second, consider the model's interpretability; some complex extensions of the DM model are designed for flexibility in capturing positive correlations but may require specialized knowledge to interpret the parameters governing the dependence structure [56].

4. Can these models handle complex experimental designs, such as longitudinal data or multiple interacting factors? While ZIBB and ZIDM are powerful for cross-sectional data, analyzing experiments with multiple factors (e.g., treatment, time) often requires integrating these models into broader frameworks. One approach is to use Generalized Linear Models (GLMs) with design matrix decomposition to separate and quantify the influence of different experimental factors on the microbial community [21].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Model Fit Indicated by Residual Diagnostics

Issue: After fitting a Beta-Binomial or DM model, diagnostic checks reveal that the model does not adequately capture the overdispersion or zero-inflation in your data.

Solution: Upgrade to a zero-inflated mixture model.

- Step 1: Assess Zero-Inflation. Test if the number of zeros in your data exceeds what is expected under a standard Beta-Binomial or DM model. This can be done using a likelihood ratio test, which has shown that a high proportion of taxa may require zero-inflation modeling [54].

- Step 2: Choose the Appropriate Model.

- For analyzing individual taxa, implement a Zero-Inflated Beta-Binomial (ZIBB) model. This is a two-part mixture model that uses a logistic component to model excess zeros and a Beta-Binomial component for the counts [54].

- For a community-level analysis that respects compositional data, implement a Zero-Inflated Dirichlet-Multinomial (ZIDM) model. This model also uses a mixture distribution to handle excess zeros and can be more flexible than the standard DM [52] [55] [53].

Problem: Inaccurate Identification of Differentially Abundant Taxa

Issue: When testing for taxa that are associated with a phenotype (e.g., disease status), you get too many false positives (Type I errors) or fail to find true associations (low power).

Solution: Employ a method that properly controls for false discoveries and leverages the mean-variance relationship.

- Step 1: Use a Constrained Overdispersion Estimate. In models like ZIBB, estimate the overdispersion parameter as a function of the mean (e.g., a polynomial relationship). This "constrained approach" borrows strength across taxa, which increases the power to detect true associations [54].

- Step 2: Account for Covariates. Ensure your model includes relevant clinical or technical covariates (e.g., age, batch effects, library size) as confounders. Both ZIBB and ZIDM frameworks allow for this adjustment [54] [52].

- Step 3: Correct for Multiple Testing. When performing univariate tests on many taxa (as with ZIBB), apply multiple testing corrections (e.g., Benjamini-Hochberg FDR control) to your p-values.

Problem: Computational Challenges or Model Non-Convergence

Issue: The model fails to converge, takes an extremely long time to run, or produces unstable parameter estimates.

Solution: Simplify the model or use more efficient algorithms.

- Step 1: Pre-filter Taxa. Remove very low-prevalence taxa (e.g., those present in less than 5% of samples) to reduce dimensionality before fitting a multivariate model like ZIDM.