OTUs vs. ASVs: A Comprehensive Guide for Metagenomic Analysis in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) and Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) for researchers and professionals in drug development and clinical research.

OTUs vs. ASVs: A Comprehensive Guide for Metagenomic Analysis in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) and Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) for researchers and professionals in drug development and clinical research. It covers the foundational concepts behind both methods, explores their practical applications and computational pipelines, offers troubleshooting and optimization strategies for real-world studies, and presents a comparative validation of their performance on ecological patterns and biomarker discovery. The goal is to equip scientists with the knowledge to select the appropriate method for their specific research objectives, particularly in the context of precision medicine and microbiome-based therapeutics.

Understanding the Core Concepts: From OTU Clustering to ASV Denoising

In microbial ecology, an Operational Taxonomic Unit (OTU) is an operational definition used to classify groups of closely related individuals based on DNA sequence similarity [1]. Originally introduced by Robert R. Sokal and Peter H. A. Sneath in 1963 in the context of numerical taxonomy, the term has evolved to become a fundamental concept in marker-gene analysis [2] [1]. OTUs serve as pragmatic proxies for "species" at different taxonomic levels, particularly for microorganisms that cannot be easily cultured or classified using traditional Linnaean taxonomy [1].

In contemporary practice, OTUs typically refer to clusters of organisms grouped by DNA sequence similarity of specific taxonomic marker genes, most commonly the 16S rRNA gene for prokaryotes and 18S rRNA gene for eukaryotes [3] [1]. These units have become the most widely used measure of microbial diversity, especially in analyses of high-throughput sequencing datasets where they provide a standardized approach for comparing microbial communities across different samples and environments [3] [4].

Table: Historical Evolution of OTU Concept

| Time Period | Definition | Primary Use | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1960s | Groups of organisms based on phenotypic traits | Numerical taxonomy | Sokal & Sneath [2] |

| 1990s-2000s | 97% 16S rRNA sequence similarity clusters | Microbial ecology | Stackebrandt & Goebel [2] |

| Present | Sequence clusters at various similarity thresholds | Microbiome studies | Multiple pipelines |

Fundamental Principles of OTU Clustering

The 97% Similarity Threshold

The conventional 97% sequence similarity threshold for defining OTUs has its origins in empirical studies linking 16S rRNA gene similarity to DNA-DNA hybridization values [2]. This threshold was proposed based on the finding that 97% similarity in 16S sequences approximately corresponded to a 70% DNA reassociation value, which had been previously established as a benchmark for defining bacterial species [2]. The 97% cutoff represents a pragmatic compromise between sequencing error inflation and true biological diversity, though this fixed threshold remains controversial and fails to account for differential evolutionary rates across taxonomic lineages [5] [6].

The traditional interpretation associates different sequence identity thresholds with various taxonomic levels: 97% for species-level classification, 95% for genus-level, and 80% for phylum-level groupings [2]. However, this interpretation represents a rough approximation rather than a biological absolute, as significant variations exist across different bacterial groups [5] [6]. For instance, some closely related species may share over 99% 16S sequence similarity, while multiple copies of the 16S rRNA gene within a single strain can differ by up to 5% in certain regions [6].

Core Assumptions and Limitations

OTU clustering operates on several fundamental assumptions. First, it presumes that sequences with high nucleotide identity belong to the same bacterial species, accounting for intra-species sequence variations while overcoming potential sequencing errors [3]. Second, it assumes that everything within an OTU shares the same function and ecological role, an assumption increasingly challenged by evidence of ecological variation among very closely related strains [3].

The approach carries significant limitations, including the constraint that different organisms with identical marker gene sequences become indistinguishable despite potential phenotypic differences [3]. Furthermore, the procedure of circumscribing diversity at a fixed sequence divergence level inevitably loses important phylogenetic information, potentially merging distinct taxonomic species or splitting single species across multiple OTUs [3] [5].

OTU Clustering Methodologies

Clustering Approaches

Three primary approaches exist for clustering sequences into OTUs [1]:

De novo clustering: Groups sequences based solely on similarities between the sequencing reads themselves without reference to existing databases. This approach can reveal novel diversity but is computationally intensive.

Closed-reference clustering: Compares sequences against a reference database and clusters those that match a reference sequence within the specified similarity threshold. This method offers consistency across studies but discards sequences not present in the reference database.

Open-reference clustering: Combines both approaches by first clustering sequences against a reference database, then clustering the remaining sequences de novo. This method preserves novel diversity while maintaining consistency for known sequences.

Table: Comparison of OTU Clustering Approaches

| Clustering Type | Advantages | Disadvantages | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| De novo | Detects novel diversity; No database dependence | Computationally intensive; Less comparable between studies | Exploratory studies of novel environments |

| Closed-reference | Fast; Consistent across studies | Discards novel sequences; Database-dependent | Multi-study comparisons; Well-characterized environments |

| Open-reference | Balances novelty and consistency; Comprehensive | Complex workflow; Still requires reference database | Most general applications |

Clustering Algorithms and Workflows

Several algorithms have been developed for OTU clustering, each with distinct methodologies:

Hierarchical clustering algorithms include methods such as:

- Average neighbor (UPGMA): Produces more robust OTUs than other hierarchical methods [7]

- Furthest neighbor (complete linkage): Provides conservative diversity estimates but is sensitive to sequencing artifacts [7]

- Nearest neighbor (single linkage): Tends to produce chain-like clusters that may connect distantly related sequences [7]

Heuristic algorithms such as UCLUST and CD-HIT offer computational efficiency for large datasets [2] [1]. Bayesian clustering methods like CROP use probabilistic models to determine optimal clusters without fixed similarity thresholds [1].

The standard workflow for OTU generation begins with quality filtering of raw sequences, followed by dereplication (identifying unique sequences), then clustering using one of the above algorithms at a specified identity threshold (typically 97%), and finally chimera detection and removal [2].

Taxonomic Assignment and Annotation

Following OTU clustering, a single representative sequence is selected from each OTU—typically the most abundant sequence or the centroid—which serves as the proxy for the entire cluster [3] [6]. This representative sequence is then taxonomically classified using reference databases such as Greengenes, SILVA, or the RDP database [3] [7]. The classification is performed using algorithms like the RDP classifier, a naïve Bayesian approach that assigns taxonomic labels based on sequence similarity to reference sequences with confidence estimates [7].

This annotation is then applied to all sequences within the OTU, operating under the assumption that the entire cluster shares the same taxonomic identity [6]. However, this approach can introduce errors when OTUs contain evolutionarily diverse sequences that would receive different taxonomic classifications if analyzed individually [6].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing Workflow

The standard pipeline for OTU-based analysis begins with DNA extraction from environmental samples, followed by PCR amplification of the target hypervariable regions of the 16S rRNA gene using universal primers [8] [6]. Common primer sets target regions such as V3-V4 or V4 alone, though the specific region amplified can significantly impact downstream results due to varying discrimination power across different hypervariable regions [3] [5].

After amplification, libraries are prepared and sequenced using high-throughput platforms such as Illumina MiSeq [8]. The resulting raw sequences undergo pre-processing including adapter removal, quality filtering, and merging of paired-end reads [8]. For OTU clustering, sequences are typically trimmed to equal length and filtered to remove low-complexity or exceptionally low-quality sequences [8] [7].

Quality Control and Validation

Robust OTU analysis requires careful quality control throughout the process. This includes:

- Mock communities: Samples with known composition used to validate the entire workflow and estimate error rates [2]

- Negative controls: Identify potential contamination introduced during sample processing [9]

- Replication: Assess technical variability and reproducibility

- Sequence quality filtering: Remove or correct sequences likely to contain errors [8]

Filtering strategies often include removing OTUs with total read counts below a certain threshold (e.g., 0.1% of total reads) to minimize the impact of spurious clusters while preserving biologically relevant signals [8]. More advanced filtering approaches include mutual information-based network analysis, which identifies and removes contaminants by assessing the strength of biological associations between taxa [9].

Critical Analysis of the 97% Threshold

Limitations of a Fixed Threshold

The conventional 97% similarity threshold faces several significant limitations when applied to short amplicons covering only one or two variable regions of the 16S rRNA gene [5]. Different hypervariable regions evolve at different rates and possess varying degrees of conservation, meaning that a fixed threshold applied to different regions will capture different levels of taxonomic resolution [3] [5].

Research has demonstrated that the compactness of OTUs varies substantially across the taxonomic tree [6]. For example, analyses of Human Microbiome Project data revealed that 80.5% of V3V5 OTUs contained at least one sequence with multiple sequence alignment-based dissimilarity (MSD) greater than 3% from the representative sequence [6]. Similarly, 12.9% of V3V5 OTUs and 19.8% of V1V3 OTUs contained sequences with taxonomic classifications that differed from their representative sequence [6].

Table: Optimal Clustering Thresholds for Different 16S rRNA Regions

| 16S Region | Recommended Threshold | Rationale | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full-length | 99% identity | Maximum resolution for species differentiation | Edgar [2] |

| V3-V4 | 97-99% identity | Balanced resolution for common Illumina protocols | [8] |

| V4 alone | 100% identity | Short region requires maximal stringency | Edgar [2] |

| Variable by family | Dynamic thresholds | Accounts for differential evolutionary rates | [5] |

Alternative Thresholds and Dynamic Approaches

Recent research has proposed various alternatives to the standard 97% threshold. Some studies suggest that 98.5-99% identity more accurately approximates species-level clusters for full-length 16S sequences [2]. The concept of "dynamic thresholds" accounts for differential evolutionary rates across taxonomic lineages by applying family-specific clustering thresholds based on the inherent variability within each taxonomic group [5].

For shorter reads targeting specific hypervariable regions, even more stringent thresholds may be necessary. One analysis recommended nearly 100% identity for the V4 region to achieve species-level resolution comparable to full-length sequences clustered at 97% [2]. These findings highlight the context-dependent nature of optimal clustering thresholds and challenge the universal application of any fixed similarity cutoff.

Comparative Analysis: OTUs vs. ASVs

Fundamental Differences in Approach

The emergence of Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) represents a significant methodological shift from traditional OTU clustering [8] [4]. While OTUs group sequences based on a fixed percent similarity threshold (typically 97%), ASVs are generated through denoising algorithms that attempt to correct sequencing errors and distinguish true biological sequences [8].

The fundamental distinction lies in their clustering methodologies: OTUs use identity-based clustering that groups sequences within a fixed percent similarity, while ASVs employ denoising approaches based on probabilistic error models that predict and correct sequencing errors before forming clusters [8]. This difference in methodology results in ASVs providing single-nucleotide resolution across the entire sequenced gene region, whereas OTUs explicitly collapse variation below the chosen threshold [4].

Ecological and Taxonomic Implications

Comparative studies have demonstrated that OTU clustering typically leads to underestimation of ecological diversity measures compared to ASV-based approaches [4]. Research on shrimp microbiota found that while family-level taxonomy showed reasonable comparability between methods, 97% identity OTU clustering produced divergent genus and species profiles compared to ASVs [8].

The choice between OTUs and ASVs also impacts the detection of organ and environmental variations, though studies suggest these biological patterns remain robust to clustering method choice [8]. However, ASV-based analyses generally provide higher resolution for detecting subtle community changes and more consistent results across different studies due to the reproducible nature of exact sequence variants [8] [4].

Table: Performance Comparison of OTU vs. ASV Methods

| Parameter | OTU Approach | ASV Approach | Biological Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diversity estimates | Generally lower alpha diversity | Higher resolution of diversity | ASVs capture more subtle diversity patterns |

| Technical reproducibility | Variable between studies | Highly reproducible | ASVs enable direct cross-study comparisons |

| Reference database dependence | High for closed-reference | Minimal dependence | ASVs better for novel diversity |

| Computational demand | Lower for simple methods | Higher for denoising | Practical considerations for large studies |

| Strain-level resolution | Limited by threshold | Single-nucleotide resolution | ASVs can distinguish ecologically distinct strains |

Table: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for OTU Analysis

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Databases | GreenGenes [3], SILVA [3], RDP [7] | Taxonomic classification and reference-based clustering | Database choice affects results; each has different curation approaches |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines | QIIME [3] [6], mothur [7] [6], UPARSE [2] | End-to-end analysis of 16S sequencing data | Pipeline choice influences OTU picking algorithm and downstream results |

| Clustering Algorithms | UCLUST [2] [1], CD-HIT [1], Bayesian CROP [1] | Grouping sequences into OTUs | Algorithm affects OTU quality and computational efficiency |

| Quality Control Tools | Decontam [9], PERFect [9], microDecon [9] | Identify and remove contaminants | Essential for accurate diversity assessment |

| PCR Reagents | Universal 16S primers (e.g., 338F/533R) [8] | Amplification of target regions | Primer choice affects taxonomic coverage and resolution |

| Mock Communities | Defined bacterial mixtures | Validation of entire workflow | Essential for estimating error rates and pipeline accuracy |

The traditional OTU clustering approach has served as the foundation of microbial ecology for decades, providing a pragmatic solution for categorizing microbial diversity in the absence of cultured isolates [3] [1]. The 97% similarity threshold, while historically valuable as an operational definition, represents an oversimplification of complex evolutionary relationships [5] [6]. Current research increasingly recognizes the limitations of fixed-threshold clustering and emphasizes the importance of methodology choice in interpreting microbial community data [8] [4].

The field continues to evolve with emerging methods such as dynamic thresholding that account for differential evolutionary rates [5] and ASV-based approaches that offer single-nucleotide resolution [8] [4]. While OTU clustering remains a valuable approach, particularly for comparative analyses with existing datasets, researchers must carefully consider the methodological implications on their biological interpretations and explicitly acknowledge these limitations in their conclusions [3] [6]. The choice between OTUs and ASVs ultimately depends on research questions, technical constraints, and the need for cross-study comparability versus fine-scale resolution [8] [4].

The analysis of microbial communities through targeted amplicon sequencing, particularly of the 16S rRNA gene, has revolutionized our understanding of microbiomes. For many years, the standard bioinformatic approach for analyzing this data relied on Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs), which cluster sequences based on a predefined similarity threshold, typically 97% identity [10] [11] [12]. While this method served the community well, it inherently sacrificed resolution for error tolerance. The field is now undergoing a significant paradigm shift toward Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs), a high-resolution denoising method that distinguishes sequence variation by a single nucleotide change without arbitrary clustering [11] [13]. This transition is driven by the need for greater precision, reproducibility, and cross-study comparability in microbial ecology, oncology, and drug development research [10] [13]. This technical guide frames the introduction of ASVs within the broader thesis of OTU versus ASV methodologies, detailing the core concepts, experimental protocols, and practical applications of this advanced denoising approach.

Core Concepts: OTUs vs. ASVs

What Are Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs)?

An Amplicon Sequence Variant (ASV) is any one of the inferred single DNA sequences recovered from a high-throughput analysis of marker genes after the removal of erroneous sequences generated during PCR and sequencing [11]. Unlike OTUs, which group sequences into clusters, ASVs represent exact, error-corrected biological sequences. Also referred to as exact sequence variants (ESVs), zero-radius OTUs (ZOTUs), or sub-OTUs (sOTUs), ASVs provide single-nucleotide resolution, enabling researchers to distinguish between closely related microbial taxa that would be grouped together by traditional OTU methods [11] [13].

Key Methodological Differences and Advantages

The fundamental difference between OTUs and ASVs lies in their approach to handling sequence variation and errors.

OTU Clustering: This traditional method groups sequences based on a similarity threshold (e.g., 97% identity). The three primary methods are:

- De novo clustering: Computationally expensive and creates clusters entirely from observed sequences without a reference database [10].

- Closed-reference clustering: Computationally efficient but dependent on a reference database, causing sequences not in the database to be dropped [10].

- Open-reference clustering: A hybrid approach that first uses closed-reference clustering and then performs de novo clustering on the remaining sequences [10]. The OTU approach "blurs" similar sequences into a consensus to minimize the influence of sequencing errors [10].

ASV Denoising: This modern approach starts by determining the exact sequences and their frequencies. It then uses a statistical error model tailored to the sequencing run to distinguish true biological sequences from technical artifacts, effectively providing a confidence measure for each exact sequence [10] [14]. The result is a set of high-resolution, reproducible sequence variants.

The table below summarizes the core differences between these two approaches.

Table 1: Core Differences Between OTU and ASV Methodologies

| Feature | OTU (Operational Taxonomic Unit) | ASV (Amplicon Sequence Variant) |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Similarity-based clustering | Error-corrected, exact sequences |

| Resolution | Coarse (typically 97% identity) | Fine (single-nucleotide) |

| Error Handling | Errors can be absorbed into clusters | Uses algorithms to denoise and correct errors |

| Reproducibility | May vary between studies and parameters | Highly reproducible across studies |

| Computational Demand | Generally less intensive | More computationally demanding |

| Dependence on References | Varies (de novo, closed, or open-reference) | Independent of reference databases |

| Primary Output | Clusters of similar sequences | Table of exact sequences and their abundances |

The advantages of ASVs are substantial. They offer higher resolution, allowing for the detection of closely related species or strains [12]. They are highly reproducible because they represent exact sequences, making comparisons between different studies straightforward [10] [11]. Furthermore, they perform superior error correction and chimera removal, leading to more reliable and accurate results [10] [12].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Constructing an ASV feature table from raw sequencing data involves a multi-step process where quality control and denoising are paramount. The following workflow outlines the key stages from data acquisition to final analysis.

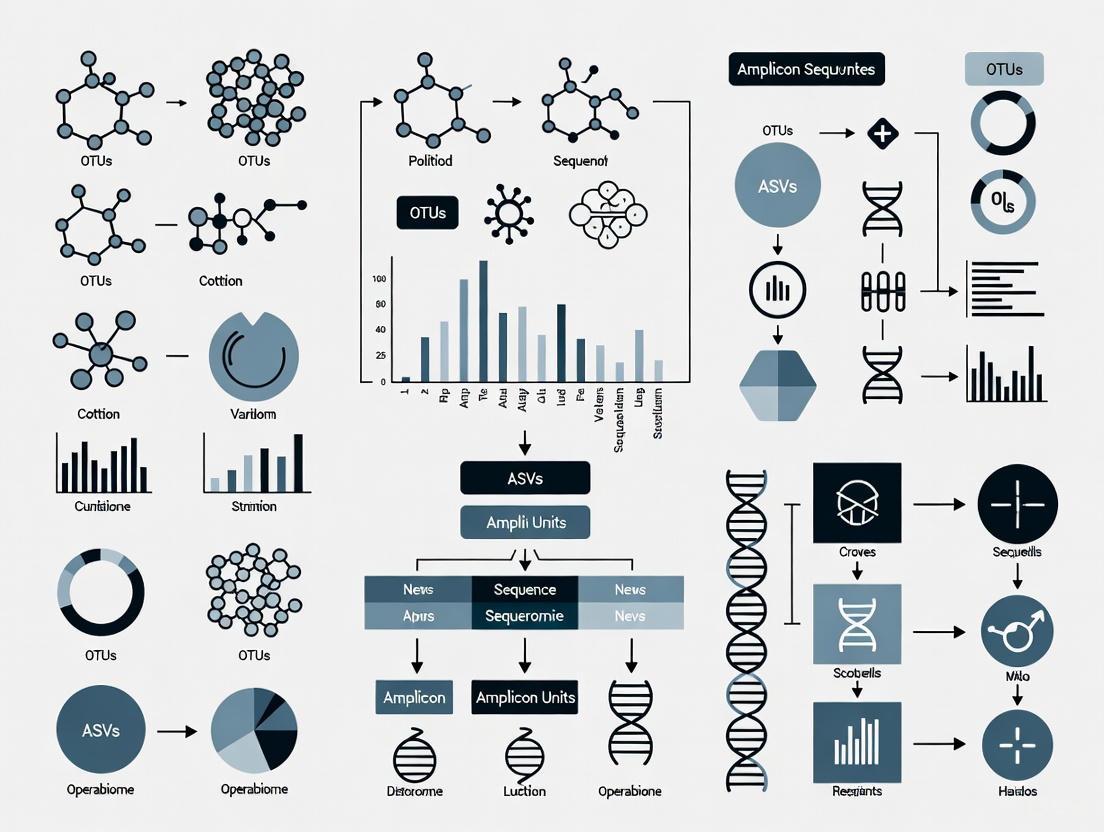

Figure 1: A generalized workflow for generating an Amplicon Sequence Variant (ASV) table from raw amplicon sequencing data, highlighting the critical denoising step.

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

The construction of an ASV table begins with high-quality amplicon sequencing data, typically from platforms like Illumina MiSeq or HiSeq [13]. The initial preprocessing stage is critical for downstream accuracy and involves:

- Quality Control: Tools like FastQC are used to assess the quality of raw sequences [13].

- Removal of Adapters and Primers: Contamination from primers or adapter sequences is removed using tools like Cutadapt [13] [14].

- Filtering and Trimming: Reads are filtered based on quality scores and trimmed to a consistent length to remove low-quality bases. This can be performed by DADA2's built-in filtering function, Trimmomatic, or similar tools [13] [14]. For paired-end reads, the forward and reverse reads are then merged using tools like PEAR [14].

Core Denoising and ASV Construction

This is the pivotal stage where ASV methods diverge from OTU clustering. Denoising algorithms model and correct sequencing errors to infer true biological sequences.

Sequence Denoising: The preprocessed reads are input into a denoising algorithm. The major tools available are:

- DADA2: Employs a parametric error model that is trained on the entire sequencing run. It uses abundance information and quality scores to infer true sequences and calculate the probability that a given read is not due to sequencer error [14] [13].

- Deblur: Uses a fixed distribution model and a sample-by-sample approach to rapidly remove predicted error-derived reads [14].

- UNOISE3: A one-pass clustering strategy that does not depend on quality scores but uses pre-set parameters to generate "zero-radius OTUs," making it computationally very fast [14].

Chimera Removal: Chimeric sequences, which are artifacts formed from two parent sequences during PCR, are identified and removed. DADA2, for example, has a built-in chimera-checking algorithm that flags ASVs which are exact combinations of more prevalent parent sequences from the same sample [10] [14].

ASV Table Generation: The final output of the denoising pipeline is an ASV feature table. This is a matrix where rows correspond to unique ASVs, columns represent samples, and cell values indicate the abundance (read count) of each ASV in each sample [13]. This table can be normalized and filtered to remove low-abundance ASVs, reducing noise for subsequent analysis.

Performance and Validation

Quantitative Comparison of Denoising Tools

Independent evaluations have been conducted to assess the performance of different ASV pipelines. One such study compared DADA2, UNOISE3, and Deblur on mock and real communities (soil, mouse, human) and found key differences [14].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Major ASV Denoising Tools

| Tool | Key Algorithmic Principle | Relative Runtime | Tendency for ASV Discovery | Best Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DADA2 | Parametric error model using quality scores | Slowest (Baseline) | Highest (may detect more rare organisms) | Studies where maximum sensitivity is desired [14] |

| UNOISE3 | One-pass clustering with pre-set parameters | >1,200x faster than DADA2 | Moderate | Large datasets where computational speed is critical [14] |

| Deblur | Fixed error model, sample-by-sample processing | 15x faster than DADA2 | Lower | Standardized workflows requiring rapid processing [14] |

The study concluded that while all pipelines resulted in similar general community structure, the number of ASVs and resulting alpha-diversity metrics varied considerably [14]. DADA2's higher sensitivity suggests it could be better at finding rare organisms, but potentially at the expense of a higher false positive rate [14].

ASVs vs. OTUs: Empirical Evidence

Research comparing ASV and OTU methods has shown that the choice of method can significantly impact ecological interpretations.

- Broad-scale Ecology: Some studies indicate that for investigating broad-scale ecological patterns, OTUs and ASVs provide similar results. One study confirmed the suitability of OTUs for this purpose, noting that ASVs only provided a slightly stronger detection of diversity [11].

- Fine-scale Resolution and Contamination: In studies requiring fine resolution, ASVs excel. For example, using a dilution series of a microbial community standard, ASV-based methods were better able to differentiate sample biomass from contaminant biomass due to their precise sequence identification [10].

- Taxonomic Consistency: A study on shrimp microbiota found that ASVs and 99% identity OTUs produced comparable taxonomy and diversity profiles at the family level. However, traditional 97% OTUs produced divergent genus and species profiles, highlighting ASVs' advantage for finer taxonomic classification [8].

Successfully implementing an ASV workflow requires a combination of bioinformatic tools, reference databases, and computational resources.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ASV Analysis

| Category | Item | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Bioinformatic Tools | DADA2, Deblur, UNOISE3 | Core denoising algorithms to infer true biological sequences from raw reads [11] [13] [14]. |

| Analysis Pipelines | QIIME 2, mothur | Integrated platforms that wrap multiple tools for an end-to-end amplicon analysis workflow, including denoising, taxonomy assignment, and diversity analysis [13]. |

| Reference Databases | SILVA, Greengenes, UNITE | Curated collections of rRNA sequences used for taxonomic annotation of the generated ASVs [13]. |

| Functional Prediction | PICRUSt2 | A tool that uses ASV tables to predict the functional potential of the microbial community based on marker gene sequences [13]. |

| Data Repositories | NCBI SRA, EMBL-EBI, MG-RAST | Public archives to access 16S rRNA amplicon data for method testing, validation, and meta-analyses [13]. |

Limitations and Critical Considerations

Despite their advantages, ASV approaches are not without limitations. A significant consideration is the risk of artificially splitting a single bacterial genome into multiple ASVs [15]. Many bacterial genomes contain multiple copies of the 16S rRNA gene, and these copies are not always identical. This intragenomic variation can lead a denoising algorithm to correctly identify multiple distinct ASVs from a single organism. One analysis of bacterial genomes found an average of 0.58 unique ASVs per copy of the full-length 16S rRNA gene [15]. For an E. coli genome (with 7 copies), this could result in a median of 5 distinct ASVs. This phenomenon can inflate diversity metrics and lead to incorrect ecological inferences if different ASVs from the same genome are interpreted as different taxa with distinct ecologies [15].

Furthermore, ASV generation is computationally more intensive than traditional OTU clustering, which can be a constraint for very large studies with limited computational resources [12]. Finally, the high resolution of ASVs may sometimes be unnecessary for studies focused solely on broad-scale ecological trends.

The adoption of Amplicon Sequence Variants represents a significant advancement in marker-gene analysis, moving the field toward higher precision, reproducibility, and comparability. While OTU clustering remains a valid approach for specific contexts, particularly for comparisons with legacy data or broad-scale ecological studies, the evidence strongly supports ASVs as the future standard for most targeted sequencing applications, especially those requiring strain-level discrimination or exploring novel environments [10] [12].

Future developments in this field are poised to further enhance the utility of ASVs. These include the integration with long-read sequencing technologies (PacBio, Nanopore) to improve sequence accuracy and length [13], multi-omics integration combining ASV data with metatranscriptomics and metabolomics to build a more functional understanding of communities [13], and the continued development of more efficient and accurate algorithms to handle the ever-increasing scale of microbiome data [13]. As these tools and technologies mature, ASV-based analysis will continue to deepen our understanding of microbial worlds in human health, disease, and the environment.

The analysis of high-throughput marker-gene sequencing data, fundamental to microbial ecology and genomics, has undergone a significant philosophical and methodological shift. This transition moves from the traditional clustering of sequences into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) to the resolution of exact Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) [16]. At its core, this shift represents a conflict between two different approaches to handling biological data: one that prioritizes pragmatic grouping through arbitrary thresholds versus one that strives for precise biological representation through exact sequences [17] [18]. The choice between these methods has profound implications for the resolution, reproducibility, and biological interpretation of microbiome research, affecting fields ranging from human health to drug development [19]. This whitepaper examines the fundamental philosophical differences between these approaches, providing a technical framework for researchers navigating this critical methodological decision.

Core Philosophical and Methodological Divergence

OTU Clustering: The Paradigm of Practical Grouping

The OTU approach is fundamentally based on similarity clustering. This method groups sequencing reads that demonstrate a predefined level of sequence identity, most commonly 97%, effectively defining a "species" level unit [19] [18] [20]. The philosophical underpinning of this approach is pragmatic: it acknowledges and attempts to mitigate sequencing errors and natural variation by binning similar sequences together, creating manageable units for ecological analysis [17]. This process inherently treats microbial diversity as a continuum that requires artificial discretization for practical analysis.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of OTU and ASV Approaches

| Feature | OTU (Operational Taxonomic Unit) | ASV (Amplicon Sequence Variant) |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Principle | Clustering by similarity threshold | Error-corrected exact sequences |

| Resolution Threshold | Arbitrary (typically 97% identity) | Single nucleotide difference |

| Biological Representation | Abstracted consensus | Exact biological sequence |

| Data Dependency | Emergent from dataset (de novo) or reference-dependent | Biological reality, independent of dataset |

| Reproducibility Across Studies | Limited without reprocessing | High with consistent labeling |

| Computational Scaling | Quadratic with study size (de novo) | Linear with sample number |

ASV Inference: The Paradigm of Exact Resolution

In contrast, the ASV approach is founded on the principle of exact sequence resolution. Rather than clustering similar sequences, ASV methods use a model of the sequencing error process to distinguish true biological sequences from technical artifacts [17] [18]. The philosophical stance here is that biological sequences represent ground truth, and the goal of analysis should be to recover this truth as accurately as possible, rather than abstracting it through clustering. This approach treats each unique biological sequence as a meaningful unit of diversity, capable of carrying ecological and functional significance [16]. ASVs therefore represent a commitment to precision and biological fidelity over analytical convenience.

Quantitative Comparative Analysis: Implications for Research Outcomes

Diversity Measurements and Ecological Interpretation

The methodological differences between OTU and ASV approaches translate directly into quantifiable differences in research outcomes. Multiple studies have demonstrated that the choice of analysis pipeline significantly influences alpha and beta diversity measures, sometimes changing the ecological signals detected [20]. Notably, ASV-based methods typically yield higher resolution data, capturing single-nucleotide differences that may represent functionally distinct microbial lineages [18].

Table 2: Impact on Diversity Metrics Across Experimental Systems

| Study System | OTU Richness | ASV Richness | Beta Diversity Concordance | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freshwater Mussel Microbiomes [20] | Overestimated compared to ASVs | More conservative estimate | Generally comparable | Pipeline choice had stronger effect than rarefaction or identity threshold |

| Shrimp Microbiota [8] | Highly variable with identity threshold (97% vs. 99%) | Consistent resolution | Comparable patterns with appropriate filtering | Family-level comparisons robust to method choice |

| Beech Species Phylogenetics [21] | Large proportions of rare variants | >80% reduction in representative sequences | All main variant types identified | ASVs captured equivalent phylogenetic information more efficiently |

Taxonomic Resolution and Biological Meaning

The implications for taxonomic resolution are equally significant. While OTU clustering at 97% identity may group together multiple closely related species or strains, ASVs can distinguish sequences that differ by as little as a single nucleotide [17] [18]. This precision enables researchers to investigate microbial communities at strain level, which can have profound functional implications. For example, different strains of Escherichia coli can range from commensal organisms to deadly pathogens, a distinction that would be lost with traditional OTU clustering but preserved with ASVs [22]. This enhanced resolution directly supports drug development efforts by enabling more precise associations between microbial strains and health outcomes.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standardized OTU Clustering Protocol

The OTU clustering workflow typically involves several standardized steps, implemented through platforms like QIIME and MOTHUR [19] [8]:

- Sequence Preprocessing: Quality filtering, trimming of low-quality bases, and removal of ambiguous bases using tools like PRINSEQ [8].

- Clustering Method Selection:

- De novo: Clustering without a reference database (computationally intensive)

- Closed-reference: Clustering against a curated database (fast but limited to known diversity)

- Open-reference: Hybrid approach combining both methods [17]

- Identity Threshold Application: Grouping sequences at a predetermined similarity threshold (typically 97% or 99%) using algorithms such as VSEARCH [8].

- Taxonomic Assignment: Mapping representative sequences to reference databases (e.g., Greengenes, SILVA) using classifiers like the RDP classifier [19].

ASV Inference Protocol

The ASV inference workflow employs a fundamentally different approach based on error modeling and exact sequence resolution [8]:

- Quality Modeling: Learning the specific error rates of the sequencing run using a parametric error model.

- Dereplication and Sample Inference: Identifying unique sequences and modeling the abundance of true biological sequences versus errors.

- Sequence Validation: Applying statistical tests to distinguish true biological sequences from artifacts, effectively creating "p-values" for each exact sequence [17].

- Chimera Removal: Identifying and removing chimeric sequences formed during PCR amplification through comparison to more abundant "parent" sequences.

- Taxonomic Assignment: Matching exact sequences to reference databases with single-nucleotide precision.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for OTU and ASV Analysis

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Method Type | Key Applications | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOTHUR [21] [20] | OTU clustering | Identity-based clustering | Traditional microbiome diversity studies | Stand-alone platform |

| QIIME 2 [8] | Pipeline framework | Supports both OTU and ASV | Flexible analysis workflows | Python-based platform |

| DADA2 [21] [17] [8] | ASV inference | Denoising algorithm | High-resolution variant analysis | R package |

| VSEARCH [8] | Sequence clustering | Identity-based clustering | OTU picking in reference-based workflows | Command-line tool |

| Deblur [18] | ASV inference | Denoising algorithm | Rapid ASV inference | QIIME 2 plugin |

| Amino-PEG8-Amine | Amino-PEG8-Amine, MF:C18H40N2O8, MW:412.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals | |

| APN-C3-PEG4-alkyne | APN-C3-PEG4-alkyne, MF:C25H31N3O6, MW:469.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Implications for Research Reproducibility and Meta-Analysis

The Consistent Labeling Advantage of ASVs

A fundamental philosophical advantage of ASVs lies in their status as consistent labels with intrinsic biological meaning [16]. Unlike OTUs, which are emergent properties of a specific dataset, ASVs represent actual DNA sequences that exist independently of any particular study. This property enables direct comparison of ASVs across different studies, facilitating meta-analyses and replication studies that are problematic with de novo OTUs [16]. When a significant association is found between a particular ASV and a condition of interest, that exact association can be tested in future studies because the ASV itself is a biologically meaningful entity that transcends the original dataset.

Computational and Practical Considerations

The consistent labeling of ASVs also provides significant practical advantages for large-scale studies and meta-analyses. Because ASVs can be inferred independently for each sample and then merged, the computational requirements scale linearly with the number of samples [16]. In contrast, de novo OTU clustering requires simultaneous processing of all sequences from all samples, with computational demands that scale quadratically with sequencing effort [16]. This makes ASV-based approaches particularly advantageous for large-scale studies and ongoing research programs where new samples are regularly added to existing datasets.

The philosophical shift from OTUs to ASVs represents more than a technical improvement—it constitutes a fundamental evolution in how researchers conceptualize and analyze microbial diversity. The arbitrary thresholds of OTU clustering offered a practical solution to the challenges of early sequencing technologies but inevitably obscured biological reality through their necessary abstractions [17] [18]. In contrast, the exact sequence resolution of ASVs embraces the complexity of microbial systems by preserving biological signals at their most precise level [16].

For researchers and drug development professionals, this transition enables more reproducible, comparable, and biologically meaningful results. The enhanced resolution of ASVs facilitates the identification of strain-level associations with health and disease, potentially revealing new therapeutic targets and diagnostic markers [22]. While OTU-based approaches will continue to have value for comparing results with historical datasets, the scientific community is increasingly recognizing ASVs as the new standard for marker-gene analysis [16] [18]. This paradigm shift promises to deepen our understanding of microbial ecosystems and enhance our ability to translate this knowledge into clinical applications.

Historical Context and the Paradigm Shift in Microbiome Informatics

The field of microbiome research has undergone a profound transformation, evolving from early microscopic observations to sophisticated sequencing technologies that now enable precise characterization of microbial communities at unprecedented resolution. This evolution has been marked by a significant paradigm shift in how we define and analyze the fundamental units of microbial diversity: the move from Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) to Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs). This transition represents more than just a technical improvement—it constitutes a fundamental change in the philosophical approach to microbial community analysis, with far-reaching implications for research reproducibility, cross-study comparisons, and clinical applications in drug development [23] [24].

The historical development of microbiome research has been characterized by several technological paradigm shifts, each enabling new perspectives on microbial communities. The discovery of the first microscopes revealed the previously invisible world of microorganisms, while the development of cultivation techniques enabled their systematic study. The introduction of molecular methods, particularly DNA sequencing and PCR, facilitated cultivation-independent community analysis through phylogenetic markers like the 16S rRNA gene. Today, next-generation sequencing technologies provide the foundation for high-resolution community profiling that underpins the OTU to ASV transition [24].

Historical Foundations: The Era of OTU Clustering

The Theoretical Basis and Methodological Approaches

Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) emerged as an early solution to a fundamental challenge in microbiome research: how to group sequencing reads into biologically meaningful units while minimizing the impact of technical errors inherent to sequencing technologies. The OTU approach is based on a clustering philosophy that groups sequences by similarity thresholds, traditionally set at 97% identity, approximating the species-level boundary in prokaryotes [23] [18].

Three primary methods were developed for OTU generation, each with distinct advantages and limitations:

- De novo clustering: A reference-free approach that creates OTU clusters entirely from observed sequences. While this method avoids reference database biases, it is computationally intensive and generates study-specific results that cannot be directly compared across studies [23].

- Closed-reference clustering: This method compares sequences to a reference database of known taxa. It is computationally efficient but completely dependent on reference sequences, causing novel taxa to be lost from analysis [23].

- Open-reference clustering: A hybrid approach that combines closed-reference clustering for known sequences with de novo clustering for remaining sequences, balancing computational efficiency with sensitivity to novel organisms [23].

Table 1: OTU Clustering Methods and Their Characteristics

| Clustering Method | Reference Dependency | Computational Demand | Novel Taxon Detection | Cross-Study Comparability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| De novo | No reference required | High | Excellent | Poor |

| Closed-reference | Complete dependency | Low | Poor | Good (with same database) |

| Open-reference | Partial dependency | Moderate | Good | Moderate |

Technical Implementation and Workflow

The OTU clustering workflow typically involved multiple processing steps: quality filtering of raw sequences, dereplication to identify unique sequences, clustering based on similarity thresholds (typically 97%), and picking representative sequences for each cluster. This process relied on algorithms implemented in tools like MOTHUR, VSEARCH, and USEARCH [18].

The 97% similarity threshold was originally chosen as it approximated the species boundary for prokaryotes based on early DNA-DNA hybridization studies. However, this arbitrary cutoff presented significant limitations, as multiple similar species could be grouped into a single OTU, and their individual identifications were lost in the resulting cluster consensus [23] [4].

The Paradigm Shift: Advent of ASV Analysis

Theoretical Foundation and Methodological Innovation

The transition to Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) represents a fundamental shift from the clustering approach to an error-correction philosophy. Rather than grouping similar sequences to average out technical errors, ASV methods employ sophisticated error models to distinguish true biological variation from sequencing artifacts, resulting in exact sequence variants that provide single-nucleotide resolution [23] [18].

ASV analysis starts by determining which exact sequences were read and their respective frequencies. These data are combined with an error model for the sequencing run, enabling statistical evaluation of whether a given read at a specific frequency represents true biological variation or technical error. This approach generates a p-value for each exact sequence, where the null hypothesis states that the sequence resulted from sequencing error. Sequences are then filtered according to confidence thresholds, leaving a collection of exact sequences with defined statistical confidence [23].

Technical Implementation and Workflow

The ASV workflow incorporates error modeling and correction as core components: quality filtering, learning error rates from the dataset itself, sample inference, and chimera removal. This process is implemented in algorithms such as DADA2 and Deblur, which have become standard tools in modern microbiome analysis [18] [4].

A key advantage of the ASV approach is its generation of reproducible, exact sequences that can be directly compared across studies without reference to a database. This feature addresses a fundamental limitation of OTU methods, where the same biological sample processed in different studies would yield different OTUs due to the clustering algorithm's sensitivity to dataset composition [23].

Comparative Analysis: OTUs vs. ASVs in Research Settings

Technical and Performance Comparisons

Multiple studies have directly compared OTU and ASV approaches to quantify their methodological differences and impacts on research conclusions. A 2022 study analyzing thermophilic anaerobic co-digestion experimental data together with primary and waste-activated sludge prokaryotic community data found that while both pipelines provided generally comparable results allowing similar interpretations, they delivered community compositions differing between 6.75% and 10.81% between pipelines [25].

A comprehensive 2024 study examining alpha, beta, and gamma diversities across 17 adjacent habitats demonstrated that OTU clustering led to marked underestimation of ecological indicators for species diversity and distorted behavior of dominance and evenness indexes compared to ASV data. The study compared two levels of OTU clustering (99% and 97%) with ASV data, finding that reference-based OTU clustering introduced misleading biases, including the risk of missing novel taxa absent from reference databases [4].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of OTU vs. ASV Methods

| Performance Metric | OTU Approach | ASV Approach | Biological Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taxonomic Resolution | Species-level (97% cutoff) | Single-nucleotide difference | ASVs enable strain-level differentiation |

| Error Handling | Averaged through clustering | Statistical error correction | ASVs reduce false positives |

| Rare Taxon Detection | Higher spurious OTUs | Better differentiation of true rare variants | ASVs more accurate for low-abundance species |

| Cross-Study Comparison | Limited comparability | Directly comparable exact sequences | ASVs enable large-scale meta-analyses |

| Computational Demand | Lower (except de novo) | Moderate to high | Context-dependent feasibility |

| Novel Taxon Discovery | Limited in closed-reference | Not dependent on reference databases | ASVs better for unexplored environments |

Impact on Diversity Assessments and Ecological Interpretation

The choice between OTU and ASV methodologies significantly influences ecological interpretations and diversity assessments in microbiome research. ASV-based analysis provides higher resolution data that more accurately captures true microbial diversity, particularly for fine-scale patterns like strain-level ecological differences that remain invisible with OTUs [18] [4].

Research has demonstrated that ASV methods outperform OTU approaches in handling common confounding factors in microbiome studies. When analyzing contamination issues using microbial community standards with known composition, ASV-based methods better distinguished sample biomass from contaminants. For chimera detection, ASVs enable simpler identification without potential reference database biases, as chimeric ASVs represent exact recombinants of more prevalent parent sequences in the same sample [23].

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Guidelines

Standardized ASV Workflow Implementation

For researchers implementing ASV-based analysis, the following protocol outlines a standardized workflow using the DADA2 pipeline within the R environment:

Quality Control and Filtering:

- Trim primers and adapters from raw sequences

- Quality filter based on error profiles:

filterAndTrim() - Set truncation length based on quality score plots

Error Rate Learning:

- Learn forward error rates:

learnErrors(filtFs, multithread=TRUE) - Learn reverse error rates:

learnErrors(filtRs, multithread=TRUE) - Visualize error rates to ensure proper convergence

- Learn forward error rates:

Sample Inference:

- Dereplicate sequences:

derepFastq() - Apply core sample inference algorithm:

dada(derep, err=errF, multithread=TRUE) - Merge paired-end reads:

mergePairs(dadaF, derepF, dadaR, derepR)

- Dereplicate sequences:

Sequence Table Construction and Chimera Removal:

- Construct sequence table:

makeSequenceTable(mergers) - Remove chimeras:

removeBimeraDenovo(seqtab, method="consensus")

- Construct sequence table:

Taxonomic Assignment:

- Assign taxonomy using reference database:

assignTaxonomy(seqtab, refFasta) - Species-level assignment:

addSpecies(taxa, refFasta)

- Assign taxonomy using reference database:

This protocol generates an ASV table of exact sequences that can be used for downstream ecological analyses and cross-study comparisons [18] [4].

Comparative Analysis Experimental Design

For studies directly comparing OTU and ASV approaches, the following experimental design ensures methodological rigor:

- Sample Selection: Include diverse sample types (e.g., environmental gradients, clinical samples) to assess method performance across different complexity levels

- Parallel Processing: Process identical raw sequence data through both OTU (e.g., VSEARCH at 97% identity) and ASV (e.g., DADA2) pipelines

- Diversity Assessment: Calculate multiple alpha diversity metrics (Shannon, Simpson, Chao1) and beta diversity measures (Bray-Curtis, Weighted Unifrac)

- Taxonomic Comparison: Assess taxonomic assignments at different taxonomic ranks (phylum to species)

- Statistical Analysis: Evaluate significant differences in community composition between methods using PERMANOVA and other multivariate statistics

This approach was successfully implemented in a 2024 study that analyzed samples from 17 adjacent habitats across a 700-meter transect, providing comprehensive assessment of how bioinformatic choices influence ecological interpretations [4].

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Microbiome Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| DADA2 | R package | ASV inference via error correction | High-resolution microbiome analysis |

| Deblur | QIIME 2 plugin | ASV inference using error profiles | Rapid ASV determination |

| QIIME 2 | Analysis platform | End-to-end microbiome analysis | Integrated workflow management |

| VSEARCH | Command-line tool | OTU clustering and analysis | Reference-based OTU picking |

| MOTHUR | Analysis pipeline | OTU clustering and community analysis | Traditional OTU-based approaches |

| SILVA Database | Reference database | Taxonomic classification | 16S rRNA gene alignment |

| Greengenes | Reference database | Taxonomic classification | 16S rRNA gene alignment |

| ZymoBIOMICS Standards | Control standards | Method validation | Pipeline quality control |

Future Perspectives and Emerging Applications

Integration with Advanced Computational Approaches

The paradigm shift from OTUs to ASVs aligns with broader trends in microbiome research toward increased computational sophistication and integration with artificial intelligence approaches. Machine learning algorithms are increasingly applied to ASV-derived data for feature selection, biomarker identification, and disease prediction [26].

Advanced AI applications in microbiome research include the use of deep learning models to analyze oceanic microbial ecosystems and predict gene functions in biogeochemical cycles. These approaches leverage the high-resolution data provided by ASV methods to identify complex patterns and relationships that were previously undetectable [27].

Knowledge Graphs and Systems Biology Approaches

The development of resources like MicrobiomeKG (a knowledge graph for microbiome research) demonstrates how ASV-derived data can be integrated into broader biological contexts. Knowledge graphs bridge various taxa and microbial pathways with host health, enabling hypothesis generation and discovery of new biological relationships through integrative analysis [28].

This systems biology approach, facilitated by the precise taxonomic resolution of ASVs, supports the advancement of personalized medicine through deeper understanding of microbial contributions to human health and disease mechanisms. The reproducibility and cross-study compatibility of ASVs make them ideally suited for large-scale integrative analyses that can power these knowledge graphs [28].

The historical transition from OTUs to ASVs in microbiome informatics represents more than a methodological upgrade—it constitutes a fundamental paradigm shift in how we conceptualize, analyze, and interpret microbial communities. This shift from clustering-based approaches to error-corrected exact sequences has enhanced the resolution, reproducibility, and comparability of microbiome research.

While OTU methods served as valuable tools during the early development of microbiome research and remain useful in specific contexts such as population studies with well-characterized reference databases, ASV approaches now represent the current gold standard for most microbiome applications. The higher resolution provided by ASVs enables detection of fine-scale patterns, more accurate diversity assessments, and better differentiation of true biological signals from technical artifacts.

For researchers and drug development professionals, adopting ASV-based approaches provides a pathway to more robust, reproducible, and clinically actionable microbiome research. The enhanced precision of ASVs supports the development of targeted interventions and personalized medicine approaches based on a more accurate understanding of host-microbiome interactions. As the field continues to evolve, the paradigm shift from OTUs to ASVs establishes a foundation for increasingly sophisticated analyses that will further unravel the complexity of microbial communities and their impacts on human health and disease.

The analysis of microbial communities through marker gene sequencing, such as the 16S rRNA gene, hinges on the method used to define the fundamental units of biodiversity. The field has witnessed a significant methodological shift from Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs), which cluster sequences based on a similarity threshold, to Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs), which resolve exact biological sequences through denoising. This transition embodies a core trade-off: sacrificing the error tolerance and computational simplicity of OTUs to gain the single-nucleotide resolution, reproducibility, and cross-study compatibility of ASVs. This technical guide delves into the mechanisms, advantages, and limitations of both approaches, providing researchers with a framework to navigate this critical choice in experimental design and data analysis. Framed within the broader thesis of ongoing methodological evolution in bioinformatics, we detail experimental protocols, present quantitative benchmarking data, and offer visualization tools to elucidate this fundamental compromise.

In targeted amplicon sequencing, the immense volume of raw sequence data must be reduced into biologically meaningful units for ecological analysis. For years, the standard unit was the Operational Taxonomic Unit (OTU), defined as a cluster of sequences similar to one another at a fixed threshold, typically 97%, which was intended to approximate species-level groupings [12]. This method provided a pragmatic way to manage data and mitigate sequencing errors through clustering. However, the inherent arbitrariness of the similarity threshold and the loss of fine-scale biological variation prompted a re-evaluation.

The emergence of Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) marks a paradigm shift. ASVs are exact, error-corrected DNA sequences inferred from the data, offering single-nucleotide resolution [29]. This approach treats the microbiome not as a collection of blurred clusters, but as a set of precise, distinct sequence variants. The debate between these methods is not merely technical but philosophical, influencing the resolution of ecological patterns, the reproducibility of findings, and the very questions a researcher can ask. This guide explores the trade-offs between the error-tolerant clustering of OTUs and the high-resolution denoising of ASVs, a decision that sits at the heart of modern microbiome informatics [18].

Methodological Foundations: Clustering vs. Denoising

Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs): The Clustering Approach

The OTU methodology is built on the principle of clustering to absorb noise. The canonical workflow involves:

- Sequence Pre-processing: Quality filtering, trimming, and merging of paired-end reads.

- Distance Calculation: Pairwise comparison of all sequences to compute a genetic distance matrix.

- Clustering: Grouping sequences into clusters based on a predefined similarity threshold (e.g., 97%) using algorithms such as greedy clustering, average neighbor, or Opticlust [30].

- Representative Sequence Selection: Choosing a single sequence (e.g., the most abundant) to represent each OTU for downstream taxonomic assignment and phylogenetic analysis.

The primary advantage of this approach is its error tolerance. By grouping similar sequences, minor variations likely caused by sequencing errors are consolidated into a consensus, effectively smoothing out technical noise [12]. This also reduces the dataset's dimensionality, which was historically advantageous for computational efficiency. However, this comes at a cost: the loss of sub-OTU biological variation. The 97% threshold is arbitrary and may inadvertently group distinct species or strain-level variants, while splitting others, leading to a blurred picture of true microbial diversity [12] [20].

Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs): The Denoising Approach

The ASV methodology replaces clustering with a systematic process of error modeling and correction. The workflow, as implemented in tools like DADA2, involves:

- Error Model Learning: The algorithm first learns the specific error rates of the sequencing run by analyzing the quality scores and patterns in a subset of the data [29]. This creates a position-specific, transition-specific error model (e.g., the probability of an A being called as a C).

- Denoising (Core Inference): Each unique sequence is compared to all others. The algorithm uses a probabilistic model to determine whether a less abundant sequence is a true biological variant or a spurious derivative (a "daughter") of a more abundant "parent" sequence generated by sequencing errors. True biological sequences are partitioned from errors [30].

- Chimera Removal: Post-denoising, sophisticated algorithms identify and remove chimeric sequences, which are artificial hybrids formed during PCR.

- Output: The final output is a table of exact, error-corrected biological sequences—the ASVs.

The foremost advantage of ASVs is high resolution, enabling the discrimination of closely related microbial strains [12]. Furthermore, because ASVs are exact sequences, they serve as consistent labels, making them directly comparable across different studies and platforms without re-processing, thus enhancing reproducibility and meta-analysis potential [31].

The following diagram illustrates the core logical difference between the two bioinformatics workflows.

The Core Trade-off: A Quantitative and Qualitative Analysis

The choice between OTUs and ASVs is a direct negotiation between error tolerance and resolution. The following table summarizes the fundamental characteristics of each approach.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of OTUs and ASVs

| Feature | OTUs (Clustering-Based) | ASVs (Denoising-Based) |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Clusters of sequences with ≥97% similarity [12] | Exact, error-corrected sequence variants [12] |

| Error Handling | Errors absorbed into clusters; tolerant of lower-quality data [12] | Errors explicitly modeled and removed; requires high-quality data [29] |

| Resolution | Low (species-level, approximate) [12] | High (strain-level, single-nucleotide) [12] |

| Reproducibility | Low (cluster boundaries depend on the dataset) [31] | High (exact sequences are universal labels) [31] |

| Computational Cost | Lower (though de novo can be intensive) [12] | Higher (due to complex error modeling) [12] |

| Reference Database | Optional (for closed-reference) or not required (for de novo) [29] | Not required for inference; used for taxonomic ID [31] |

| Best Suited For | Comparisons with legacy data; broad ecological trends; limited computing resources [12] | Novel discovery; strain-level analysis; meta-analyses; reproducible workflows [12] [31] |

Quantitative Benchmarks from Mock Community Studies

Objective evaluation using mock microbial communities (samples with known composition) reveals the performance trade-offs. A comprehensive 2025 benchmarking study using a complex mock of 227 bacterial strains provides critical insights [30]:

- Error Rates vs. Splitting/Merging: The study found that ASV algorithms, particularly DADA2, produced consistent outputs but suffered from over-splitting (generating multiple ASVs from a single biological variant). In contrast, OTU algorithms, led by UPARSE, achieved clusters with lower error rates but with more over-merging (lumping distinct biological variants into a single OTU) [30].

- Resemblance to True Community: Despite their respective limitations, both UPARSE (OTU) and DADA2 (ASV) showed the closest resemblance to the intended mock community composition in terms of alpha and beta diversity metrics [30].

Other studies corroborate and expand on these findings. Research on freshwater microbial communities found that the choice between OTUs and ASVs had a stronger effect on measured diversity than other methodological choices like rarefaction. Specifically, ASV-based methods (DADA2) often resulted in lower richness estimates than OTU-based methods (MOTHUR), as they were less likely to interpret rare errors as genuine diversity [20]. Furthermore, a study on 5S-IGS amplicons in beech trees concluded that DADA2 ASVs were more effective and computationally efficient, identifying all main genetic variants while significantly reducing the dataset's complexity (>80% reduction in representative sequences) compared to MOTHUR OTUs, which generated large proportions of rare and inference-wise redundant variants [21].

Table 2: Performance Comparison Based on Mock Community Studies

| Performance Metric | OTU Approach | ASV Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Error Rate | Lower in final clusters [30] | Effectively controlled by denoising [30] |

| Over-splitting | Less common [30] | More common (multiple ASVs per strain) [30] |

| Over-merging | More common (lumping distinct variants) [30] | Less common [30] |

| Richness Estimation | Often overestimates due to errors [20] | More accurate, but may underestimate if too conservative [20] |

| Data Reduction | Moderate (clustering reduces data size) | High (denoising removes errors; fewer redundant sequences) [21] |

Experimental Protocols for Method Comparison

For researchers seeking to validate or compare these methods, the use of mock communities is essential. Below is a detailed protocol based on current benchmarking practices [30].

Protocol: Benchmarking OTU and ASV Algorithms with a Mock Community

Objective: To objectively compare the error rates, taxonomic fidelity, and diversity estimates of different OTU and ASV algorithms using a microbial community of known composition.

Materials and Reagents:

- Mock Community: A commercially available, defined mix of genomic DNA from 20-200+ bacterial strains (e.g., ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standard or the HC227 mock community [30] [29]).

- Wet-lab Reagents: Primers for the target gene region (e.g., 16S rRNA V4 region), PCR master mix, sequencing kit (e.g., Illumina MiSeq).

- Bioinformatics Software:

Experimental Workflow:

- Sequencing: Amplify the mock community DNA using standard protocols for your chosen gene region. Sequence on an Illumina MiSeq or similar platform to generate paired-end reads.

- Uniform Pre-processing: To ensure a fair comparison, subject all raw sequence files (FASTQ) to identical pre-processing steps.

- Quality Check: Use FastQC to assess read quality.

- Primer Trimming: Use a tool like cutPrimers to remove adapter and primer sequences [30].

- Read Merging & Filtering: Merge paired-end reads and apply strict quality filtering (e.g., maximum expected error threshold, removal of ambiguous bases). Subsample to an equal number of reads per sample (e.g., 30,000) for standardization [30].

- Parallel Processing: Process the pre-processed data through each OTU and ASV pipeline independently, following their recommended best-practice workflows.

- Output Analysis: Compare the outputs against the known ground truth of the mock community.

- Error Rate: Calculate the number of spurious sequences (not in the reference) per pipeline.

- Compositional Fidelity: Assess how well the relative abundance of each expected taxon is recovered.

- Alpha and Beta Diversity: Compare the richness and diversity indices (e.g., Shannon, Chao1) and community distances (e.g., Unifrac, Bray-Curtis) to the expected values.

- Over-merging/Splitting: Count the number of output units (OTUs/ASVs) assigned to each known reference strain.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Tools

The following table details key materials and software essential for conducting research in this field.

Table 3: Research Reagent and Tool Solutions for OTU/ASV Analysis

| Item Name | Type | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standard | Mock Community | A defined mix of 8 bacteria and 2 yeasts with known genome sequences; used for benchmarking pipeline accuracy and detecting contamination [29]. |

| HC227 Mock Community | Mock Community | A highly complex mock of 227 bacterial strains from 197 species; provides a challenging benchmark for algorithm performance [30]. |

| DADA2 (R Package) | Software / ASV Pipeline | The most widely used ASV inference tool; uses a parametric error model and sample inference for denoising [20] [30]. |

| MOTHUR | Software / OTU Pipeline | A comprehensive, well-established open-source software suite for OTU clustering and general microbial community analysis [20]. |

| UPARSE | Software / OTU Pipeline | A widely used algorithm for greedy OTU clustering; often cited for high performance in mock community studies [30]. |

| SILVA Database | Reference Database | A curated database of aligned ribosomal RNA sequences; used for taxonomic assignment of OTUs or ASVs and alignment in pre-processing [30]. |

| Illumina MiSeq | Sequencing Platform | A popular next-generation sequencer for amplicon studies, producing 2x300bp paired-end reads suitable for denoising algorithms [30]. |

| AQX-435 | AQX-435|Potent SHIP1 Activator for Cancer Research | |

| Arformoterol maleate | Arformoterol | Arformoterol is a selective long-acting beta-2 adrenergic receptor agonist (LABA) for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

The evolution from OTUs to ASVs represents the field's growing demand for precision, reproducibility, and data interoperability. The fundamental trade-off is clear: OTUs offer robustness to noise and computational simplicity at the expense of biological resolution, while ASVs provide exquisite detail and cross-study validity at a higher computational cost and with a risk of over-discerning inconsequential variation.

The current consensus, supported by a growing body of literature, strongly favors ASVs as the standard unit for new studies [31]. Their advantages in reproducibility and meta-analysis are simply too great to ignore for a field moving toward larger, more collaborative science. However, OTUs retain their utility for specific contexts, such as integrating with vast legacy datasets or when computational resources are a primary constraint.

Future developments will likely focus on refining denoising algorithms to better handle intra-genomic variation and PCR artifacts, further closing the gap between the inferred ASV table and the true biological community. The core trade-off will persist, but the balance continues to shift toward resolution, making ASVs the definitive tool for the next generation of microbiome research.

Practical Implementation: Pipelines, Tools, and Workflow Strategies

The analysis of microbial communities through high-throughput sequencing of marker genes, such as the 16S rRNA gene for bacteria and the ITS region for fungi, relies heavily on robust bioinformatic pipelines to distinguish true biological signals from sequencing errors. For over a decade, the field has been dominated by two complementary approaches: Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) and Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs). OTUs cluster sequences based on a predefined similarity threshold (typically 97%), operating under the assumption that sequences differing by less than this threshold likely belong to the same taxonomic unit. In contrast, ASVs are generated by denoising algorithms that resolve sequences down to single-nucleotide differences, providing a higher-resolution representation of microbial diversity without the need for arbitrary clustering thresholds. This technical guide details the standard methodologies for OTU generation using two widely adopted pipelines, mothur and QIIME 2, with a focus on the integration of the high-performance VSEARCH tool. Within the broader thesis of OTU/ASV research, understanding the technical implementation, comparative performance, and appropriate application contexts of these pipelines is paramount for generating reliable, reproducible data in fields ranging from microbial ecology to drug development.

Core Concepts: OTUs vs. ASVs

The choice between OTU clustering and ASV denoising represents a fundamental decision in amplicon sequencing analysis workflows.

- Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs): This traditional approach involves clustering sequencing reads based on a percent identity threshold. A 97% similarity threshold is commonly used as a proxy for species-level classification. This method effectively reduces the impact of sequencing errors by grouping similar sequences but may mask genuine biological variation by combining distinct taxa.

- Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs): ASVs are generated by denoising algorithms that model and correct sequencing errors, resulting in biologically realistic sequences. This method provides higher resolution, improves reproducibility, and facilitates cross-study comparisons because the same ASV will have the same sequence identity in different studies.

Recent research highlights the contextual advantages of each method. A 2024 study on fungal ITS data found that while ASVs offered high resolution, OTU clustering at 97% similarity produced more homogeneous results across technical replicates and was suggested as the most appropriate option for that specific data type [32]. Conversely, a 2025 phylogenetic study on 5S-IGS amplicon data concluded that DADA2 (an ASV tool) identified all main genetic variants while generating far fewer rare features, making it more computationally efficient and effective for tracing evolutionary pathways [33].

Table 1: Comparison of OTU and ASV Approaches

| Feature | OTU (Clustering-based) | ASV (Denoising-based) |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Clusters of sequences with a defined similarity (e.g., 97%) | Exact biological sequences inferred by error correction |

| Resolution | Lower (groups sequences) | Higher (single-nucleotide) |

| Reproducibility | Moderate (varies with clustering parameters) | High (sequence-based) |

| Computational Load | Generally lower for clustering itself | Generally higher for denoising |

| Handling of Rare Taxa | May lump rare variants with abundant ones | Can better distinguish rare biological variants |

The Mothur Pipeline for OTU Generation

The mothur pipeline, developed by the Schloss lab, provides a comprehensive, all-in-one software environment for processing amplicon sequence data. Its SOP is a meticulously curated workflow designed to minimize sequencing and PCR errors while generating high-quality OTUs [34].

Detailed Methodology

- Assembling Paired-End Reads: The first step uses the

make.contigscommand, which combines paired-end reads from FASTQ files. The algorithm aligns the forward and reverse reads, and at positions of disagreement, it uses quality scores to decide the consensus base—calling an 'N' if quality scores differ by less than 6 points [34]. Input is a file (e.g.,stability.files) specifying sample names and their corresponding forward and reverse read files [34] [35]. - Filtering and Alignment: Sequences are filtered based on length, ambiguity, and homopolymers. The resulting high-quality sequences are aligned against a reference alignment database (e.g., SILVA [34]) using the

align.seqscommand to ensure sequences are oriented in the same direction for downstream analysis. - Pre-clustering and Chimera Removal: To reduce the impact of random sequencing errors, the

pre.clustercommand is used to merge sequences that are within a few nucleotides of each other. Chimeric sequences, artifacts from PCR amplification, are then identified and removed using tools like UCHIME [34] [36]. - OTU Clustering and Taxonomy Assignment: The final step involves calculating pairwise distances between sequences and clustering them into OTUs using the

dist.seqsandclustercommands. mothur's OptiClust algorithm is a robust and memory-efficient method for this task [32]. Finally, theclassify.seqscommand assigns taxonomic classification to each OTU by comparing representative sequences to a reference database (e.g., RDP or SILVA) [34] [35].

The QIIME 2 Pipeline with VSEARCH

QIIME 2 (Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology 2) is a powerful, plugin-based framework that supports diverse analysis methods. It can leverage VSEARCH, an open-source, 64-bit alternative to USEARCH, for performing reference-based and de novo OTU clustering [37].

The Role of VSEARCH