Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing: A Comprehensive Guide to Microbiome Functional Analysis for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive overview of shotgun metagenomic sequencing for microbiome functional analysis, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing: A Comprehensive Guide to Microbiome Functional Analysis for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of shotgun metagenomic sequencing for microbiome functional analysis, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, from distinguishing shotgun sequencing from 16S rRNA methods to exploring its ability to characterize unculturable microbes and reveal functional genetic potential. The piece details methodological workflows and applications in pharmaceutical development, including antimicrobial resistance tracking and therapeutic discovery. It also addresses critical troubleshooting considerations for complex samples and data analysis, and concludes with validation strategies and comparative analyses against other microbiome profiling techniques. This resource serves as a practical guide for leveraging metagenomic insights in clinical and biotechnological applications.

Unlocking Microbial Dark Matter: Foundational Principles of Shotgun Metagenomics

What is Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing? Definition and Core Principles

Definition and Core Principles

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing is a next-generation sequencing (NGS) method that involves comprehensively sampling and sequencing all genes from all organisms present in a given complex sample [1]. The core principle of this technique lies in its non-targeted approach: instead of amplifying specific marker genes, all genomic DNA extracted from a sample—whether from microbes, viruses, or other biological entities—is randomly fragmented into small pieces, much like a shotgun would break something into pieces [2]. These small DNA fragments are then sequenced in parallel, generating millions of reads that are subsequently analyzed and stitched back together using sophisticated bioinformatics tools [2].

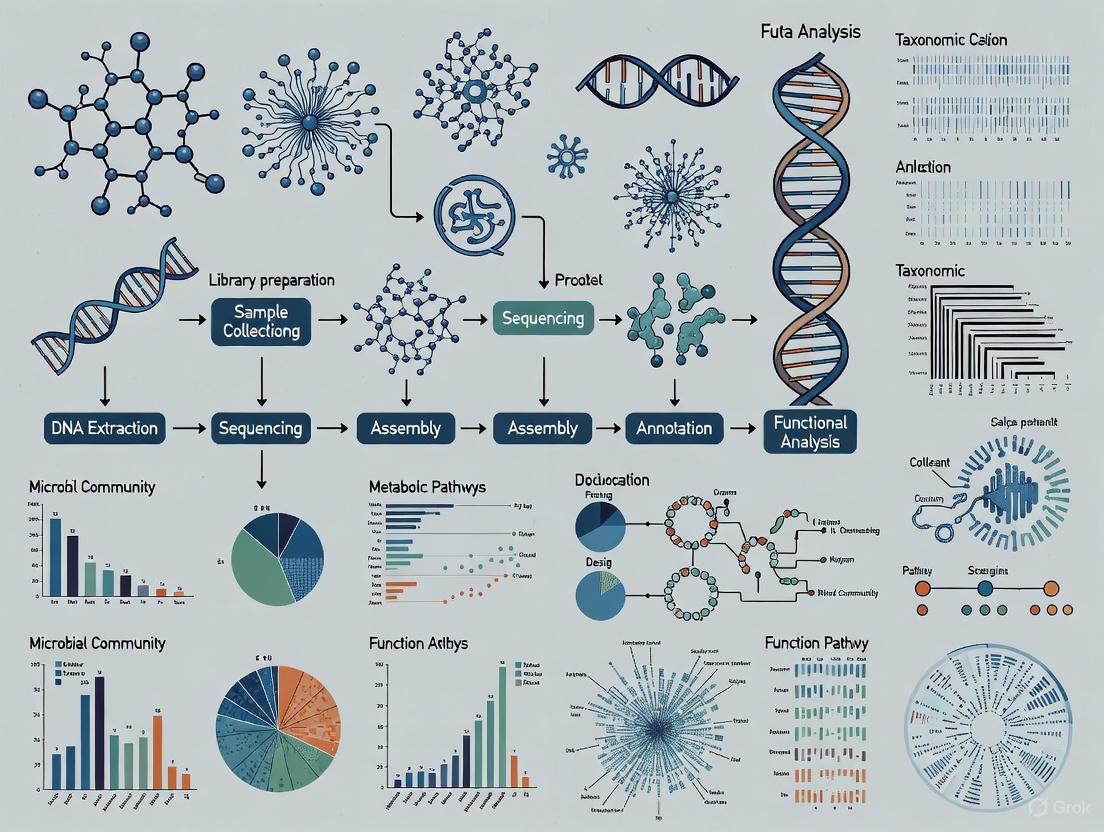

The fundamental workflow can be broken down into several key stages, as illustrated below:

This approach enables researchers to simultaneously evaluate bacterial diversity and detect the abundance of microbes in various environments, including the study of unculturable microorganisms that are otherwise difficult or impossible to analyze [1]. Unlike targeted methods such as 16S rRNA gene sequencing, shotgun metagenomics provides a complete picture of the microbial community by capturing genetic material from all domains of life—bacteria, archaea, fungi, and viruses—while also enabling researchers to elucidate the functional potential of these communities [3] [2] [4].

Key Advantages and Comparative Analysis

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing offers several distinct advantages over targeted sequencing approaches, which are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of shotgun metagenomic sequencing versus 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing

| Feature | Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing | 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Scope of Detection | All microorganisms (bacteria, archaea, fungi, viruses) [2] [4] | Primarily bacteria and archaea only [4] |

| Taxonomic Resolution | Species to strain level [2] | Typically genus level, sometimes species [5] |

| Functional Insights | Direct assessment of functional genes and metabolic pathways [3] [2] | Limited to phylogenetic inference (e.g., PICRUSt) [6] |

| PCR Bias | Minimal (no targeted amplification) [2] | Significant (primers target specific regions) [5] |

| Reference Database Dependence | Dependent on genomic databases [2] [5] | Dependent on 16S-specific databases (e.g., SILVA, Greengenes) [5] |

| Cost Considerations | Higher cost, especially for deep sequencing [2] | More cost-effective [5] |

| Bioinformatic Complexity | High computational requirements [2] | Less computationally intensive [5] |

| Host DNA Contamination | More challenging when host DNA overwhelms microbial DNA [2] [7] | Less affected due to targeted amplification |

The higher resolution of shotgun metagenomics allows for species to strain-level discrimination, a significant advantage over 16S sequencing which typically classifies groups to the genus or species level [2]. Additionally, since there is no PCR amplification step targeting specific regions, shotgun sequencing avoids primer bias, copy-number bias, PCR artifacts, and chimeras that can complicate amplicon-based approaches [2].

Experimental Protocol: A Detailed Workflow

Sample Collection and Preservation

The initial step in any shotgun metagenomics study involves careful sample collection and preservation. Sample types can range from human fecal samples to environmental samples such as soil, water, or air [2]. Three critical factors must be considered:

- Sterility: Sample containers must be sterile to prevent contamination from external microbes [2].

- Temperature: To preserve microbial integrity, samples should be frozen immediately after collection at -20°C or -80°C, or snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Freeze-thaw cycles should be avoided as they compromise sample integrity [2].

- Time: Samples should be frozen as quickly as possible after collection. When immediate freezing isn't feasible, temporary storage at 4°C or use of preservation buffers may be suitable alternatives [2].

For human microbiome studies, particularly those involving stool samples, consistency in collection timing and method is crucial for reproducible results.

DNA Extraction

DNA extraction is performed using commercial kits that employ a combination of chemical and physical methods to separate DNA from other cellular components [2]. The key steps include:

- Lysis: Breaking open cells through chemical processes (enzymes) and mechanical processes (vigorous shaking/mixing) to release DNA [2].

- Precipitation: Separating DNA from other cell contents using salt solutions and alcohol [2].

- Purification: Washing the precipitated DNA to remove impurities and resuspending it in an aqueous solution [2].

For challenging samples containing hard-to-lyse structures (e.g., spores) or inhibitors (e.g., humic acids in soil), additional enzymatic or physical treatment steps may be necessary [2]. The choice of DNA extraction kit significantly influences the observed microbial community structure and affects inter-study comparisons.

Library Preparation and Sequencing

Library preparation involves preparing the extracted DNA for sequencing through the following steps:

- DNA Fragmentation: Mechanical or enzymatic methods break DNA into short fragments suitable for sequencing [2].

- Adapter Ligation: Molecular 'barcodes' or index adapters are ligated to DNA fragments to enable sample multiplexing and identification after sequencing [2].

- Library Cleanup: Size selection and purification ensure the DNA library is optimized for sequencing [2].

Sequencing is typically performed using high-throughput platforms such as Illumina, which offers short read lengths (150-300 bp) with high accuracy, or long-read technologies like Oxford Nanopore and PacBio that facilitate assembly of complex genomic regions [3]. The selection of sequencing platform depends on the specific research goals, required read length, and throughput needs [2].

Bioinformatics Analysis

Bioinformatic analysis represents the most computationally intensive phase of shotgun metagenomics. Two primary analytical approaches are employed:

- Read-Based Analysis: Sequencing reads are directly compared to reference databases of microbial marker genes using tools such as Kraken, MetaPhlAn, and HUMAnN [2]. This approach requires less sequencing coverage but is limited by database completeness.

- Metagenome Assembly: Sequencing reads are assembled into partial or complete microbial genomes using tools like MEGAHIT or MetaSPAdes [3] [2]. This approach enables discovery of novel species and strains but demands greater sequencing depth and computational resources.

Table 2: Essential bioinformatics tools for shotgun metagenomic data analysis

| Analysis Step | Tool Examples | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Quality Control | Trimmomatic, Fastp, MultiQC [3] | Remove low-quality reads and sequencing artifacts |

| Host DNA Removal | KneadData, Bowtie2 [8] | Filter out host-derived sequences |

| Metagenome Assembly | MEGAHIT, MetaSPAdes, MetaVelvet [3] | Assemble sequencing reads into contigs |

| Taxonomic Profiling | Kraken, MetaPhlAn, SHOGUN, Woltka [6] [2] | Classify reads taxonomically |

| Functional Annotation | HUMAnN, KEGG, TaxonFinder [3] | Identify functional genes and metabolic pathways |

Recent computational advances such as "sequential co-assembly" have demonstrated significant reductions in assembly time and memory requirements, making metagenomic analysis more accessible in resource-constrained settings [9].

Applications in Microbial Research

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing has enabled groundbreaking research across multiple disciplines:

Human Health and Disease

In biomedical research, shotgun metagenomics has been instrumental in linking microbial communities to human health and disease. Studies of pediatric ulcerative colitis have revealed that affected individuals harbor a dysbiotic and less diverse gut microbial population with distinct differences from healthy children [8]. Similar approaches in colorectal cancer research have identified microbial signatures associated with disease progression, including enrichment of species such as Parvimonas micra and various Fusobacterium species [5]. The predictive power of microbial profiling for disease status has shown remarkable accuracy, with area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) values reaching 0.90 in some studies [8].

Environmental Monitoring

In environmental science, shotgun metagenomics provides unprecedented insights into microbial ecosystems. Applications include:

- Soil Microbiome Analysis: Assessing microbial diversity in relation to soil health and fertility, with studies demonstrating that high-fertility soils exhibit greater bacterial diversity, particularly among nitrogen-cycling groups essential for ecosystem functioning [3].

- Water Quality Monitoring: Identifying microbial contaminants and understanding microbial community dynamics in aquatic ecosystems [3].

- Airborne Pathogen Detection: Comprehensive analysis of airborne microbial communities in urban environments to monitor potential pathogens and assess public health risks [3].

Industrial and Food Microbiology

Industrial applications leverage shotgun metagenomics to identify and classify microorganisms in food products, fermented foods, and industrial processes. This enables quality control, pathogen detection, and optimization of biotechnological processes [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential research reagents and kits for shotgun metagenomic sequencing

| Reagent/Kits | Manufacturer/Example | Function |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | QIAamp Powerfecal DNA Kit [8], NucleoSpin Soil Kit [5] | Extraction of high-quality DNA from complex samples |

| Library Preparation Kits | Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit [8] | Preparation of sequencing libraries from extracted DNA |

| Sequenceing Platforms | Illumina NextSeq500 [8], HiSeq Series [3], Oxford Nanopore [3] | High-throughput DNA sequencing |

| Host DNA Removal | KneadData [8] | Bioinformatic filtering of host-derived sequences |

| Positive Control Standards | Commercially available microbial communities | Quality control and protocol validation |

| DBCO-NHCO-PEG4-amine | DBCO-NHCO-PEG4-amine, CAS:1255942-08-5, MF:C29H37N3O6, MW:523.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| DBCO-PEG4-NHS ester | DBCO-PEG4-NHS ester, MF:C34H39N3O10, MW:649.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Technical Considerations and Methodological Optimization

Sequencing Depth Considerations

Sequencing depth—the number of sequencing reads aligning to a reference region in a genome—critically impacts data quality. Greater sequencing depth provides stronger evidence for the presence of organisms, particularly low-abundance community members [1]. While traditional shotgun sequencing requires millions of reads per sample, "shallow shotgun sequencing" has emerged as a cost-effective alternative, providing adequate discriminatory power with as few as 500,000 reads per sample while enabling higher discriminatory and reproducible results compared to 16S sequencing [1] [6].

Contamination and Quality Control

As shotgun sequencing detects all genomic DNA in a sample, there is an increased risk of sequencing DNA from unwanted, non-microbial sources. For example, human-associated microbiome studies may generate a high proportion of human reads, with only a small fraction deriving from microbial DNA [2]. Both experimental and computational strategies must be employed to address this challenge, including:

- Implementation of negative controls to identify potential contaminants [2]

- Bioinformatics tools for host DNA removal (e.g., KneadData, Bowtie2 against host genomes) [8]

- Careful sample processing protocols to minimize external contamination [2]

The following diagram illustrates the complete shotgun metagenomic sequencing workflow with key decision points:

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing represents a powerful and transformative approach for studying complex microbial communities without the limitations of cultivation or targeted amplification. By providing comprehensive insights into both taxonomic composition and functional potential, this method has advanced our understanding of microbial ecology in diverse environments, from the human body to ecosystems worldwide. While the approach demands significant computational resources and bioinformatics expertise, ongoing methodological improvements—such as shallow sequencing and efficient assembly algorithms—continue to enhance its accessibility. As reference databases expand and analytical tools mature, shotgun metagenomics will undoubtedly remain a cornerstone technique in microbial research, enabling new discoveries and applications across scientific disciplines.

In microbiome research, the choice of sequencing methodology is foundational, dictating the depth and breadth of biological insight one can attain. While 16S rRNA gene sequencing (16S) has been a workhorse for microbial community profiling, shotgun metagenomic sequencing (shotgun) provides a comprehensive view of all genetic material in a sample, enabling unparalleled functional analysis [10]. This Application Note delineates the technical and practical distinctions between these two principal methods, with a specific emphasis on their utility for inferring and understanding microbial function. The content is framed within the context of advanced research aimed at microbiome functional analysis, providing drug development professionals and scientists with the protocols and data comparisons necessary to inform their experimental design.

Fundamental Technical Differences

The core distinction between these methods lies in their scope and underlying approach. 16S sequencing is a form of amplicon sequencing that relies on the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to amplify a single, highly conserved gene—the 16S ribosomal RNA gene—which serves as a phylogenetic marker for identifying and quantifying bacteria and archaea [11] [10]. In contrast, shotgun metagenomics is an untargeted approach that involves fragmenting all the DNA in a sample into millions of small pieces, sequencing them, and then reconstructing the genomic content bioinformatically [2] [1]. This fundamental difference is illustrated below.

Quantitative Comparative Analysis

Performance Metrics and Capabilities

A direct comparison of performance metrics is critical for selecting the appropriate methodology. The table below synthesizes key comparative data from recent studies.

Table 1: Comparative performance of 16S rRNA and shotgun metagenomic sequencing

| Feature | 16S rRNA Sequencing | Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing | Experimental Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taxonomic Resolution | Genus-level (species-level possible but with high false positives) [12] | Species and strain-level resolution [13] [12] | Jovel et al., 2016: Shotgun provided improved genus- and species-level classification [10] |

| Taxonomic Coverage | Bacteria and Archaea only [11] [13] | Multi-kingdom: Bacteria, Archaea, Fungi, Viruses, Protists [2] [13] | |

| Functional Profiling | Indirect prediction (e.g., PICRUSt); does not capture true functional diversity [13] [12] | Direct characterization of functional genes and pathways [2] [13] | |

| Sensitivity (Genera Detection) | Detects only part of the microbial community [14] [5] | Higher power to identify less abundant taxa with sufficient reads [14] | Tettamanti et al., 2024: 16S showed sparser data and lower alpha diversity compared to shotgun [5] |

| Quantitative Concordance | Abundance correlated with shotgun for shared taxa, but gives greater weight to dominant bacteria [5] | More comprehensive and symmetrical relative species abundance distribution [14] | Raimondi et al., 2021: Shotgun RSA distributions were more symmetrical; 16S was patchy and skewed [14] |

| Differential Abundance Power | Lower; identified 108 significant genera (caeca vs. crop) [14] | Higher; identified 256 significant genera (caeca vs. crop) [14] | Raimondi et al., 2021: Shotgun found 152 changes missed by 16S; 16S found 4 changes missed by shotgun [14] |

Practical Considerations for Study Design

Beyond performance, several practical factors influence method selection, particularly in a drug development context.

Table 2: Practical considerations for selecting a sequencing method

| Factor | 16S rRNA Sequencing | Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Cost per Sample | ~$50 USD [13] | Starting at ~$150 USD; shallow shotgun can approach 16S cost for stool samples [13] |

| Bioinformatics | Beginner to intermediate expertise; well-established pipelines (QIIME, MOTHUR) [11] [13] | Intermediate to advanced expertise; more complex pipelines (MetaPhlAn, HUMAnN) [2] [13] |

| Ideal Sample Type | All types, especially low microbial biomass samples (e.g., skin swabs, tissue) [13] [12] | Samples with high microbial biomass (e.g., stool); host DNA removal may be needed for other types [13] [12] |

| Host DNA Interference | Low (PCR step enriches for 16S gene) [12] | High (sequences all DNA); can be mitigated by sequencing depth or host depletion [13] [12] |

| Minimum DNA Input | Low (can be <1 ng due to PCR amplification) [12] | Higher (typically >1 ng/μL); techniques for low biomass exist [12] |

| Reference Databases | Well-curated (SILVA, Greengenes, RDP) [13] [10] | Larger but less curated (RefSeq, GenBank); dependent on genome quality [13] [10] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

Principle: This protocol involves the targeted amplification and sequencing of hypervariable regions of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene to determine taxonomic composition [11] [15].

Table 3: Research reagents for 16S rRNA sequencing

| Reagent / Kit | Function |

|---|---|

| DNeasy PowerLyzer PowerSoil Kit (Qiagen) or equivalent | DNA extraction from complex samples, removing inhibitors [5] |

| Primers targeting hypervariable regions (e.g., V3-V4, V4) | PCR amplification of specific 16S rRNA gene regions [11] [10] |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Accurate amplification of the target region with low error rate [11] |

| Magnetic Beads for Size Selection | Cleanup of PCR amplicons to remove primers and impurities [11] |

| SILVA, Greengenes, or RDP Database | Reference databases for taxonomic classification of sequences [10] [5] |

Procedure:

- Sample Collection and DNA Extraction:

- Collect sample (e.g., stool, swab) using sterile techniques and freeze immediately at -20°C or -80°C to preserve microbial integrity [11].

- Extract genomic DNA using a specialized kit (e.g., DNeasy PowerLyzer Powersoil kit). The choice of extraction kit significantly impacts the microbial profile observed and must be consistent across a study [5].

Library Preparation:

- Amplification: Perform PCR using primers that flank the chosen hypervariable region(s) (e.g., V3-V4) of the 16S rRNA gene [11] [5].

- Indexing: Incorporate unique molecular barcodes (indices) into each sample's amplicons during a second, limited-cycle PCR to enable sample multiplexing [11] [13].

- Clean-up: Purify the final amplicon library using magnetic beads to remove contaminants and select for the correct fragment size [11].

Sequencing:

- Quantify the purified libraries, pool them in equimolar ratios, and sequence on an Illumina MiSeq or similar platform, typically generating 2x250 bp or 2x300 bp paired-end reads [11].

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Quality Control: Trim primers and filter reads based on quality and length using tools like DADA2 [5].

- Inference: Generate Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) or Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) to represent unique biological sequences [14] [5].

- Taxonomy Assignment: Classify ASVs/OTUs by aligning them to a 16S-specific reference database (e.g., SILVA) [10] [5].

- Functional Prediction (Indirect): Use tools like PICRUSt to predict functional potential based on the identified taxonomy, acknowledging this is an inference and not a direct measurement [13].

Protocol for Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing

Principle: This protocol involves the untargeted sequencing of all DNA fragments in a sample, allowing for simultaneous taxonomic profiling at high resolution and direct assessment of functional potential [2] [1].

Table 4: Research reagents for shotgun metagenomic sequencing

| Reagent / Kit | Function |

|---|---|

| NucleoSpin Soil Kit (Macherey-Nagel) or equivalent | Comprehensive DNA extraction for diverse microbial communities [5] |

| Tagmentation Enzyme / Fragmentation Kit | Random fragmentation of genomic DNA into short inserts [13] |

| Indexing Adapters (Illumina) | Ligation of unique barcodes for sample multiplexing and sequencing primers |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines: MetaPhlAn, Kraken2, HUMAnN2 | Tools for taxonomic profiling and functional analysis from raw reads [2] [13] |

Procedure:

- Sample Collection and DNA Extraction:

- Follow stringent collection and preservation protocols as for 16S. Extract total genomic DNA using a robust kit (e.g., NucleoSpin Soil Kit) designed to lyse a wide range of microbes [5]. For samples with high host DNA (e.g., tissue), consider implementing a host DNA depletion step.

Library Preparation:

- Fragmentation: Fragment the purified DNA mechanically or enzymatically (e.g., via tagmentation) to a desired size (e.g., 300-500 bp) [13].

- Adapter Ligation: Ligate sequencing adapters containing unique dual indices (UDIs) to the fragmented DNA [2] [10].

- Optional PCR: Perform a limited-cycle PCR to amplify the library if input DNA is low.

- Clean-up and Quality Control: Purify the library and validate its size distribution and concentration using an instrument such as a Bioanalyzer.

Sequencing:

- Pool libraries and sequence on a high-throughput platform (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq) to achieve the desired depth. For functional analysis, deeper sequencing (e.g., 10-20 million reads per sample) is often required compared to shallow sequencing for taxonomy alone [1].

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Pre-processing: Remove low-quality reads and adapter sequences. For clinical samples, filter out reads aligning to the host genome (e.g., GRCh38) using Bowtie2 [5].

- Taxonomic Profiling: Assign reads to taxonomic units using marker-based (e.g., MetaPhlAn) or alignment-based (e.g., Kraken2) tools against genomic databases like RefSeq [2] [10].

- Functional Profiling: Align reads to functional databases (e.g., KEGG, eggNOG) using tools like HUMAnN2 to quantify the abundance of genes and metabolic pathways directly from the metagenomic data [2] [13].

Application in Microbial Functional Analysis

The capacity of shotgun sequencing to directly profile genes confers a decisive advantage for investigating the functional potential of microbiomes, a critical aspect in therapeutic development. Shotgun data can identify antibiotic resistance genes, virulence factors, and biosynthetic pathways for metabolite production [2] [13]. Evidence from large human studies suggests that functional metagenomic data may provide more power for identifying differences between 'healthy' and 'diseased' microbiomes than taxonomic data alone [13] [10].

For instance, in colorectal cancer (CRC) research, shotgun sequencing has been instrumental in defining microbial signatures not only by taxonomy (e.g., Fusobacterium, Parvimonas micra) but also by the collective genetic capabilities of the dysbiotic community [5]. This direct functional insight is unattainable with 16S sequencing, where function must be predicted indirectly, often missing strain-specific functions and novel genes [13].

Shotgun and 16S sequencing provide two distinct lenses for examining microbial communities. 16S rRNA sequencing remains a powerful, cost-effective tool for large-scale, targeted surveys of bacterial and archaeal composition, particularly in studies where budget and computational resources are primary constraints, or for sample types with high host contamination.

However, for research focused on microbiome functional analysis, shotgun metagenomic sequencing is unequivocally the superior choice. Its ability to provide high-resolution taxonomic classification across all domains of life and, most importantly, to directly interrogate the functional gene content of a microbiome, delivers a comprehensive view of the community's genetic potential. As the field of microbiome research increasingly shifts toward understanding function and mechanism in drug development, shotgun metagenomics, including the cost-effective shallow shotgun approach for suitable sample types, is becoming the indispensable standard.

The vast majority of the microbial world has historically been inaccessible to scientific investigation due to one significant challenge: the inability to cultivate these organisms in laboratory settings. This phenomenon, first recognized by Robert Koch in the 19th century when he observed that only a limited number of microorganisms from samples grew on potato substrates, continues to impede research today [16]. Environmental microbiologists estimate that less than 2% of environmental bacteria can be cultured using standard laboratory techniques, while approximately 50% of oral microorganisms resist cultivation, with similar or higher figures anticipated for other body sites like the colon [16]. The significance of this challenge is profound; we remain largely ignorant of bacterial life on Earth, potentially missing novel pathogens, beneficial organisms, and unique metabolic pathways that could revolutionize fields from medicine to biotechnology.

The term "unculturable" does not imply that these microorganisms cannot ever be cultured, but rather that their specific growth requirements are unknown or cannot be replicated with current standard laboratory methodologies [17]. Many exist in a state known as "viable but non-culturable" (VBNC), where they maintain low metabolic activity but refuse to divide on conventional culture media [18]. This VBNC state represents a survival strategy for numerous bacterial species when faced with unfavorable growth conditions, including inappropriate temperature, pH, nutrient limitation, or antibiotic stress [18]. Understanding and overcoming these cultivation limitations is essential for comprehensive microbiome research, particularly in the context of shotgun metagenomic sequencing and functional analysis that aims to characterize complete microbial communities and their interactions with hosts.

Understanding Unculturable Microorganisms

Defining the Unculturable Microbiome

Unculturable microorganisms are those that have not yet been successfully grown and maintained in isolation under controlled laboratory conditions, despite their demonstrable presence and activity in natural environments [19] [18]. Their existence is primarily inferred through culture-independent molecular techniques that detect their genetic material or gene expression directly from environmental samples. This "microbial dark matter" represents a significant knowledge gap in microbiology, as the vast majority of microbial diversity on Earth—estimated to be over 99% of species—remains uncultivated [20] [18]. This limitation profoundly impacts microbiome research, as we cannot fully understand microbial community structure, function, or host-microbe interactions without accessing these hidden members.

Reasons for Uncultivability

Multiple interconnected factors contribute to the challenge of cultivating environmental microorganisms in laboratory settings:

Complex nutritional requirements: Many unculturable microorganisms have highly specific nutrient needs that are not replicated in standard synthetic media. Some have acquired mutations in essential synthetic pathways through evolution and depend on metabolic byproducts from other community members [16]. For instance, Bacteroides forsythus, associated with periodontitis, has an absolute requirement for N-acetyl muramic acid, a peptidoglycan component it cannot synthesize independently [16].

Disrupted bacterial communication networks: Microbes in natural environments exist in complex communication networks mediated by bacterial cytokines and signaling molecules. The separation of bacteria on solid media disrupts these networks, potentially explaining why some organisms fail to grow in isolation [16]. Resuscitation-promoting factors (Rpf) discovered in Micrococcus luteus stimulate growth of other Gram-positive bacteria at picomolar concentrations, demonstrating the importance of such signaling [16].

Inability to simulate native environments: Laboratories cannot fully replicate the complex, dynamic conditions of natural environments, including subtle physicochemical gradients, microenvironments, and community interactions that are essential for some microorganisms [18]. This is particularly challenging for extremophiles adapted to specialized niches with unique combinations of temperature, pressure, salinity, or other factors.

Microbial interdependence: Many microorganisms exist in obligate symbiotic relationships where they depend on other species for essential nutrients, growth factors, or waste removal [16] [17] [18]. The "Black Queen Hypothesis" suggests some microbes shed genes for essential functions, relying instead on other community members to provide these public goods [19].

Low abundance and slow growth rates: In many environments, some microbial species exist at low abundance or have extremely slow growth rates, making them difficult to detect and isolate before faster-growing species dominate the culture [18].

Table 1: Primary Factors Contributing to Microbial Uncultivability

| Factor Category | Specific Challenges | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Nutritional Requirements | Specific nutrient needs, auxotrophy, unknown growth factors | Bacteroides forsythus requires N-acetyl muramic acid [16] |

| Environmental Conditions | Unable to replicate native physicochemical parameters, oxygen sensitivity | Difficulties culturing anaerobes without proper redox conditions [18] |

| Microbial Interactions | Disrupted signaling, dependency on other species | Catellibacterium nectariphilum requires helper organisms [17] |

| Biological State | Viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state, dormancy | Over 100 species can enter VBNC state [18] |

Shotgun Metagenomics: A Culture-Independent Approach

Principles of Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing represents a transformative approach for studying unculturable microorganisms by bypassing the need for cultivation entirely. This next-generation sequencing method involves extracting DNA directly from environmental or clinical samples, fragmenting it into small pieces, and sequencing all DNA fragments in parallel [1] [7]. The resulting sequences are then computationally analyzed to reconstruct taxonomic profiles and functional potential without requiring prior knowledge of the organisms present [7]. This approach stands in contrast to targeted methods like 16S rRNA gene sequencing, which only amplifies and sequences specific phylogenetic marker genes, thereby limiting insights into the overall functional capacity of microbial communities [7] [14].

The power of shotgun metagenomics lies in its ability to provide comprehensive sampling of all genes from all organisms in a complex sample [1]. This enables researchers to evaluate bacterial diversity and detect microbial abundance while simultaneously accessing genetic information about functional capabilities, including metabolic pathways, virulence factors, and antibiotic resistance genes [1] [21]. For unculturable microorganisms, this method provides a window into their genetic makeup and potential ecological roles that would otherwise remain inaccessible through culture-dependent approaches.

Comparison with 16S rRNA Sequencing

While 16S rRNA sequencing has been the workhorse of microbial ecology for decades, shotgun metagenomics offers several distinct advantages for studying unculturable microorganisms, particularly in the context of functional analysis:

Table 2: Comparison of 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing vs. Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing

| Parameter | 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing | Shotgun Metagenomics |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Target | Amplifies only 16S rRNA hypervariable regions [14] | Sequences all genomic DNA fragments [1] [14] |

| Taxonomic Resolution | Typically genus-level, sometimes species-level [14] | Species to strain-level differentiation possible [21] |

| Functional Insights | Limited to inference from phylogenetic relationships [7] | Direct identification of functional genes and pathways [1] [7] |

| Coverage of Diversity | Primarily bacteria and archaea with universal primers [7] | All domains (bacteria, archaea, viruses, eukaryotes) [21] |

| Detection Sensitivity | May miss low-abundance taxa [14] | Better detection of rare community members with sufficient sequencing depth [14] |

| Quantitative Accuracy | Subject to PCR amplification biases [7] | More directly quantitative, though with own biases [14] |

Research comparing these methodologies directly demonstrates that shotgun sequencing detects a substantially greater proportion of microbial diversity. One study found that shotgun sequencing identified 256 statistically significant differences in genera abundance between gut compartments, while 16S sequencing detected only 108 differences [14]. Additionally, the less abundant genera detected exclusively by shotgun sequencing proved biologically meaningful in discriminating between experimental conditions [14].

Diagram 1: Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing Workflow

Experimental Protocols for Studying Unculturable Microbes

Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

Proper sample collection and processing are critical for accurate metagenomic analysis, as biases introduced at these stages can profoundly affect downstream results:

Sample Collection: Collect samples using standardized methods appropriate for the environment being studied (e.g., sterile swabs for body sites, core samplers for soil, filtration for water) [21]. Immediately preserve samples using stabilization solutions like DNA/RNA Shield to prevent microbial community shifts and nucleic acid degradation [21]. For human gut microbiota studies, sample multiple gastrointestinal compartments when possible, as community composition varies significantly between locations [14].

DNA Extraction: Utilize mechanical and enzymatic lysis methods capable of breaking diverse cell walls (Gram-positive, Gram-negative, fungal) [21]. The ZymoBIOMICS DNA Mini Kit and similar systems provide standardized protocols for efficient DNA extraction from complex samples. Include appropriate controls such as extraction blanks to detect contamination and standardized microbial communities (ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standard) to assess technical variability and efficiency [21]. Quantify DNA using fluorescence-based methods (e.g., Qubit) rather than UV absorbance, as the latter is less accurate for complex microbial mixtures.

Library Preparation and Sequencing

Library preparation converts extracted DNA into sequencing-ready fragments:

DNA Fragmentation: Use controlled enzymatic or mechanical fragmentation to generate appropriately sized DNA fragments (typically 200-500bp for Illumina platforms) [20]. The Illumina DNA Prep kit provides a standardized approach for this process.

Adapter Ligation: Attach platform-specific sequencing adapters with unique dual indexes (UDIs) to enable sample multiplexing and prevent index hopping issues [21]. UDIs are essential for accurate sample identification in pooled sequencing runs.

Sequencing Parameters: For complex microbial communities, aim for sufficient sequencing depth to detect rare community members. While requirements vary by community complexity, studies suggest a minimum of 500,000 reads per sample for meaningful analysis, with 2-5 million reads providing better coverage for diverse communities [20] [14]. Paired-end sequencing (2×150 bp) on Illumina platforms (NovaSeq, NextSeq) provides sufficient read length and quality for most metagenomic applications [21].

Bioinformatic Analysis Pipeline

The computational analysis of metagenomic data involves multiple steps to transform raw sequences into biological insights:

Quality Control and Preprocessing: Process raw sequencing reads using tools like FastQC for quality assessment and Trimmomatic or Cutadapt for adapter removal and quality filtering. Remove host-derived sequences if working with host-associated samples using tools like DeconSeq or Bowtie2 alignment to host genomes [7].

Assembly and Binning: For high-complexity samples, assemble quality-filtered reads into contigs using metaSPAdes or MEGAHIT [7] [20]. The success of assembly varies dramatically with community complexity—while simple communities like acid mine drainage biofilms showed 85% of reads assembling into contigs, highly diverse soil communities may see less than 1% assembly [20]. Group contigs into genome bins based on sequence composition (GC content, k-mer frequencies) and abundance profiles across samples [7] [20].

Taxonomic Profiling: Classify sequences using reference-based methods against comprehensive databases. K-mer based approaches like those implemented in SourMash provide strain-level taxonomic resolution when using databases such as GTDB (Genome Taxonomy Database) or NCBI that contain over 77,000 reference strains across all kingdoms [21].

Functional Annotation: Identify protein-coding genes in assembled contigs or directly from reads using Prodigal or FragGeneScan. Annotate predicted genes against databases like UniRef (gene families), KEGG (pathways), and MetaCyc (metabolic pathways) to determine functional potential [7] [21]. Specialized databases like CARD for antibiotic resistance genes and VFDB for virulence factors enable detection of specific functions relevant to human health [21].

Table 3: Key Bioinformatics Tools for Metagenomic Analysis

| Analysis Step | Recommended Tools | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Quality Control | FastQC, Trimmomatic, Cutadapt | Assess read quality, remove adapters, filter poor sequences |

| Host Decontamination | DeconSeq, Bowtie2 | Identify and remove host-derived sequences |

| Assembly | metaSPAdes, MEGAHIT | Reconstruct longer contigs from short reads |

| Binning | MetaBAT2, MaxBin2 | Group contigs into putative genomes |

| Taxonomic Classification | SourMash, Kraken2, MetaPhlAn | Assign taxonomy to sequences |

| Functional Annotation | Prodigal, HUMAnN3, DIAMOND | Identify genes and metabolic pathways |

| Visualization & Statistics | Phyloseq, LEfSe, STAMP | Compare communities, identify differentially abundant features |

Applications in Drug Development and Microbiome Research

Pharmacomicrobiomics: Drug-Microbiome Interactions

The study of how genetic and phenotypic diversity in the microbiome affects therapeutic outcomes—pharmacomicrobiomics—represents a promising application of metagenomics in drug development [22]. The human microbiome encodes a vast repertoire of enzymatic activities that can directly modify drug compounds, affecting their efficacy, toxicity, and pharmacokinetics [22]. At least 50 drugs are known to be metabolized by bacteria, though in most cases the specific microbial species and genetic determinants remain unidentified [22]. Notable examples include the activation of the antiviral sorivudine by gut bacterial metabolism, which can lead to toxic interactions with fluoropyrimidine chemotherapy, and the inactivation of the cardiac drug digoxin by specific gut bacterial strains [22].

Shotgun metagenomics enables comprehensive profiling of these drug-microbiome interactions through several approaches:

Culture Collection Screens: High-throughput coincubation of representative human gut bacterial strains with drug compounds, followed by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry to monitor drug transformation [22]. This approach directly identifies metabolically active strains but provides limited sampling of microbial diversity.

Ex Vivo Fecal Incubations: Incubation of drugs with complex stool samples to capture community-level metabolism, though interstrain antagonism may mask some metabolic activities [22].

Functional Metagenomics: Cloning of microbial DNA from unculturable organisms into suitable hosts (typically E. coli) followed by screening for drug-metabolizing activities [22]. This approach can directly link metabolic functions to genetic elements without requiring cultivation of the source organism.

Metagenome-Wide Association Studies: Correlation of microbial genes and pathways with drug response variability in human populations, potentially identifying microbial biomarkers for treatment personalization [22].

Mining Unculturable Microbes for Novel Therapeutics

Unculturable microorganisms represent an extensive untapped resource for novel therapeutic compounds, including antibiotics, immunosuppressants, and anti-cancer agents. The biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) encoding these compounds can be identified directly from metagenomic data, even when the producing organisms cannot be cultured [20]. Studies of diverse environments have revealed that uncultured microorganisms harbor a tremendous diversity of BGCs, many with novel architectures suggesting previously unknown chemical entities.

Functional metagenomics enables the discovery of these compounds by expressing DNA from uncultured microorganisms in heterologous hosts. This approach involves extracting environmental DNA, cloning large fragments into bacterial artificial chromosomes or other vectors, transforming suitable host strains, and screening for bioactivities of interest [20]. Successes include the discovery of novel antibiotics such as turbomycins and terragines from soil metagenomes, demonstrating the potential of this approach for drug discovery [20].

Research Reagent Solutions for Metagenomic Studies

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Metagenomic Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Preservation Solutions | Stabilize microbial community composition at collection, prevent nucleic acid degradation | DNA/RNA Shield (Zymo Research) [21] |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Efficient lysis of diverse microorganisms, minimal bias | ZymoBIOMICS DNA Mini Kit [21] |

| Library Preparation Kits | Fragment DNA, add sequencing adapters, index samples | Illumina DNA Prep with Unique Dual Indexes [21] |

| Metagenomic Standards | Control for technical variability, assess process efficiency | ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standard [21] |

| Reference Databases | Taxonomic classification and functional annotation | GTDB, NCBI, UniRef, KEGG, MetaCyc [21] |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines | Integrated analysis of metagenomic data | DRAGEN Metagenomics, HUMAnN3, SourMash [1] [21] |

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing has revolutionized our ability to study unculturable microorganisms, providing unprecedented access to the genetic diversity and functional potential of previously inaccessible microbial dark matter. By combining sophisticated molecular techniques with advanced computational analysis, researchers can now characterize microbial community membership, reconstruct metabolic pathways, and identify novel genes of biomedical interest—all without requiring laboratory cultivation of the source organisms.

The implications for drug development and personalized medicine are profound. As we deepen our understanding of how unculturable members of the human microbiome influence drug metabolism, disease susceptibility, and treatment outcomes, we move closer to truly personalized therapeutic approaches that account for both human and microbial genetic variation. The continued development of cultivation techniques, sequencing technologies, and bioinformatic tools will further enhance our ability to mine this untapped resource, potentially yielding novel therapeutic compounds and transformative insights into host-microbe interactions that shape human health and disease.

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing represents a transformative approach in microbial ecology, enabling comprehensive analysis of genetic material directly from environmental, clinical, or industrial samples [23]. Unlike targeted amplicon sequencing (e.g., 16S rRNA gene sequencing), this technique sequences all genomic DNA present in a sample, providing unprecedented access to the taxonomic composition and functional potential of complex microbial communities [2]. The term "shotgun" derives from the process of fragmenting DNA into numerous small pieces that are sequenced and subsequently reassembled computationally [2]. This culture-independent method has revolutionized our understanding of microbial ecosystems across diverse fields including human health, environmental microbiology, and biotechnology [23] [2].

The analytical pipeline for shotgun metagenomic data constitutes a critical framework for transforming raw genetic fragments into biologically meaningful insights. This multi-step process involves quality control, taxonomic profiling, functional annotation, and advanced analyses such as strain-level characterization and metabolic pathway reconstruction [24] [23]. The selection of appropriate tools and parameters at each stage significantly impacts the accuracy and biological relevance of the final results, making a thorough understanding of the entire workflow essential for researchers embarking on microbiome studies [25] [26].

Experimental Design and Sample Preparation

Sample Collection Considerations

Rigorous sample collection protocols are fundamental to obtaining reliable metagenomic data. Three critical factors must be considered during sample acquisition: sterility, temperature, and timing [2]. Sample containers must be sterile to prevent contamination from exogenous microbes. Temperature control is essential for preserving microbial integrity; samples should be frozen immediately at -20°C or -80°C, or snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Freeze-thaw cycles adversely affect microbiome consistency, making aliquoting advisable before freezing. When immediate freezing is impossible, temporary storage at 4°C or preservation buffers can maintain sample integrity for hours to days before processing [2].

Sample selection must account for substantial temporal and spatial variations in microbiomes. Consistent sampling protocols across a study population ensure comparability between samples. In clinical contexts such as the study of gut microbiota during acute pancreatitis recovery, rectal swabs collected following standardized procedures (cleaning with soap, water, and 70% alcohol, followed by sterile swab insertion to 4-5 cm depth) provide representative samples when direct fecal collection is impractical [27].

DNA Extraction and Library Preparation

DNA extraction typically employs commercial kits using combined chemical and mechanical methods to lyse cells, precipitate DNA, and purify nucleic acids [2]. The choice of extraction kit significantly influences the observed microbial community structure, affecting inter-study comparisons. Difficult-to-lyse structures (e.g., spores) may require additional enzymatic or heat treatments. For shotgun metagenomics, library preparation involves fragmenting DNA (mechanically or enzymatically), ligating molecular barcodes (index adapters) for sample multiplexing, and cleanup to ensure appropriate fragment size and purity [2].

Computational Analysis Pipeline

Quality Control and Host DNA Removal

Quality control represents the critical first step in computational analysis, addressing sequencing errors that can overestimate microbial diversity and cause erroneous taxonomic assignments [23]. Tools like fastp [27], Trimmomatic [25], and FastQC [25] perform adapter trimming, quality filtering, and read length selection. The fastp tool (v0.23.0) efficiently removes sequencing adapters, eliminates low-quality reads (average quality score <20), and discards short sequences (<50 bp after trimming) [27].

Host DNA removal is particularly important for samples with high host contamination (e.g., clinical specimens from skin or tissues). KneadData [25], BWA [27], or Bowtie2 [26] align reads against host reference genomes (e.g., human) to identify and remove contaminating sequences. In the acute pancreatitis study, BWA (v0.7.17) mapped reads to the human genome, effectively depleting host-derived sequences [27].

Table 1: Essential Tools for Metagenomic Data Preprocessing

| Tool | Function | Key Parameters | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| fastp | Quality control and adapter trimming | Quality threshold (Q20), min length 50 bp | [27] |

| FastQC | Quality assessment | Generates interactive QC reports | [25] |

| KneadData | Host read removal | Reference database of host genome | [25] |

| Bowtie2 | Host read alignment and removal | Sensitive local alignment | [26] |

| BWA | Host read removal | Efficient mapping to reference | [27] |

Taxonomic Profiling

Taxonomic classification assigns microbial identities to sequencing reads, enabling community composition analysis. Two primary approaches exist: read-based classification using marker genes or whole genomes, and assembly-based approaches that reconstruct longer sequences before classification [26].

MetaPhlAn4 utilizes unique clade-specific marker genes for efficient taxonomic profiling [25]. Kraken2 employs k-mer-based classification against comprehensive genomic databases [25]. Meteor2 represents a recent advancement that leverages environment-specific microbial gene catalogs for enhanced sensitivity, particularly for low-abundance species [24]. Benchmark tests demonstrate that Meteor2 improves species detection sensitivity by at least 45% compared to MetaPhlAn4 in both human and mouse gut microbiota simulations [24].

Table 2: Taxonomic Profiling Tools and Performance Characteristics

| Tool | Method | Database | Sensitivity Improvement | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MetaPhlAn4 | Clade-specific marker genes | ChocoPhlAn | Baseline | [25] [24] |

| Kraken2 | k-mer matching | Custom genomic database | Not specified | [25] |

| Meteor2 | Environment-specific gene catalogs | Custom MSP-based | 45% vs MetaPhlAn4 | [24] |

| Kaiju | Protein-level classification | Reference protein databases | High MCC at species/genus | [26] |

Functional Annotation

Functional annotation identifies metabolic capabilities and biochemical pathways within microbial communities, connecting taxonomic composition to potential ecosystem functions [28]. HUMAnN3 is a widely-used pipeline that maps reads to protein families (UniRef90) and pathway databases (MetaCyc) to quantify functional potential [25]. Meteor2 provides integrated taxonomic, functional, and strain-level profiling (TFSP) using microbial gene catalogs annotated with KEGG Orthology (KO), carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes), and antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) [24].

In functional abundance estimation, Meteor2 demonstrates 35% improved accuracy compared to HUMAnN3 based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarity metrics [24]. eggNOG-mapper and GO FEAT offer alternative functional annotation approaches, reporting Orthologous Groups identifiers and Gene Ontology (GO) terms, respectively [26].

Metagenome Assembly and Binning

For deeper insights into microbial communities, especially for discovering novel organisms, metagenome assembly reconstructs longer contiguous sequences (contigs) from short reads [23]. MEGAHIT and MetaSPAdes are widely used assemblers that efficiently handle complex metagenomic data [25]. Subsequent binning groups contigs into metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) using sequence composition and abundance patterns across samples [23].

MetaWRAP provides a comprehensive binning pipeline that refines and evaluates MAGs [25]. In the acute pancreatitis study, researchers mapped quality-controlled reads to representative genes with 95% identity using SOAPaligner (v2.21) to assess gene abundance [27]. EasyMetagenome supports both assembly-based analysis and binning, incorporating tools like MetaProdigal for gene prediction, CD-HIT for gene clustering, and Salmon for contig coverage estimation [25].

Integrated Analysis Pipelines

All-in-One Pipeline Solutions

Several integrated pipelines streamline the entire metagenomic analysis workflow, providing standardized approaches from raw reads to biological interpretation:

EasyMetagenome offers a user-friendly, flexible pipeline supporting quality control, read-based analysis, assembly-based analysis, and binning [25]. It includes over 150 bioinformatics tools and generates publication-ready visualizations. The pipeline is freely available at https://github.com/YongxinLiu/EasyMetagenome [25].

MEDUSA performs comprehensive metagenomic analysis including preprocessing, assembly, alignment, taxonomic classification, and functional annotation [26]. It supports user-built dictionaries to transfer annotations between different functional identifiers, enhancing flexibility in results interpretation.

MetaLAFFA specializes in annotating functional capacities in shotgun metagenomic data with native compute cluster integration [28]. It processes raw FASTQs through host read filtering, duplicate read removal, quality trimming, and functional annotation using KEGG orthology groups and pathway mappings.

Meteor2 employs environment-specific microbial gene catalogs for unified taxonomic, functional, and strain-level profiling [24]. Its database currently includes 10 ecosystems with 63,494,365 microbial genes clustered into 11,653 metagenomic species pangenomes (MSPs).

Table 3: Integrated Metagenomic Analysis Pipelines

| Pipeline | Key Features | Supported Analyses | Installation | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EasyMetagenome | User-friendly, 150+ tools | QC, read-based, assembly-based, binning | GitHub repository | [25] |

| MEDUSA | Flexible functional annotation | Preprocessing, assembly, taxonomy, function | Conda | [26] |

| MetaLAFFA | Cluster integration | Functional annotation, pathway mapping | Conda | [28] |

| Meteor2 | Environment-specific gene catalogs | Taxonomic, functional, strain-level profiling | Open-source | [24] |

Data Visualization and Interpretation

Effective visualization is crucial for interpreting complex metagenomic data. ggplot2 in R provides powerful, customizable graphics for creating publication-quality figures [29]. Alpha-diversity analysis (e.g., Shannon index) using R packages "vegan" and "reshape2" quantifies within-sample microbial diversity [27]. Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) visualizes beta-diversity patterns, revealing similarities and differences in microbial community structure across samples [27].

Color selection in biological data visualization should follow established guidelines to enhance clarity and accessibility [30]. Key principles include: identifying data nature (nominal, ordinal, interval, ratio), selecting appropriate color spaces (e.g., CIE Lab/Luv for perceptual uniformity), checking color context, assessing color deficiencies, and ensuring web/print compatibility [30].

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Shotgun Metagenomics

| Category | Item | Function | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Collection | Sterile containers | Prevent exogenous contamination | DNA/RNA-free tubes |

| Preservation buffers | Maintain sample integrity before freezing | Commercial stabilization solutions | |

| DNA Extraction | DNA extraction kits | Nucleic acid isolation from complex samples | MP-soil FastDNA Spin Kit for Soil [27] |

| Enzymatic treatments | Enhance lysis of resistant structures | Lysozyme, proteinase K | |

| Library Preparation | Fragmentation enzymes | DNA shearing for library construction | Mechanical or enzymatic fragmentation |

| Index adapters | Sample multiplexing | Unique molecular barcodes | |

| Sequencing | Sequencing platforms | High-throughput DNA sequencing | Illumina HiSeq 4000 [27] |

| Control libraries | Quality assessment of sequencing run | PhiX control library | |

| Computational | Reference databases | Taxonomic and functional classification | KEGG [27], GTDB, UniRef90 [28] |

| Analysis pipelines | Streamlined data processing | EasyMetagenome [25], MEDUSA [26] |

Application Case Study: Gut Microbiota in Acute Pancreatitis Recovery

A recent investigation exemplified the complete shotgun metagenomic workflow in studying gut microbiota dynamics during acute pancreatitis (AP) recovery [27]. Researchers collected rectal swabs from 12 AP patients of varying severity during both acute and recovery phases, with four healthy controls. After DNA extraction using MP-soil FastDNA Spin Kit, paired-end sequencing was performed on an Illumina HiSeq 4000 platform [27].

The analytical pipeline included: (1) quality control with fastp (v0.23.0) including adapter removal, quality filtering (Q20 threshold), and length selection (>50 bp); (2) host DNA removal using BWA alignment to human genome; (3) gene abundance assessment via SOAPaligner mapping to representative genes (95% identity); (4) taxonomic and functional profiling; (5) statistical analysis including α-diversity (Shannon index) and PCoA using R packages "vegan" and "reshape2"; and (6) functional annotation against KEGG database using Diamond [27].

This comprehensive approach revealed that during AP recovery, microbial diversity remained decreased with increasing beneficial bacteria (Bacteroidales) in mild AP but elevated harmful bacteria (Enterococcus) in severe cases. Functional analysis identified signaling pathways showing opposite trends in recovery phases, providing insights into microbial community restructuring during convalescence [27].

The analytical pipeline for shotgun metagenomic sequencing represents a sophisticated framework transforming raw genetic data into biological understanding. From meticulous sample preparation through computational analysis to visual interpretation, each stage requires careful consideration of tools and parameters appropriate for the specific research question. Current pipelines like EasyMetagenome, MEDUSA, and Meteor2 offer increasingly integrated solutions, while functional annotation tools like HUMAnN3 and Meteor2 provide deeper insights into microbial community capabilities.

As sequencing technologies evolve and computational methods advance, the pipeline from genetic fragments to biological meaning will continue to refine our understanding of complex microbial ecosystems across diverse environments. The integration of long-read sequencing, improved reference databases, and machine learning approaches promises even more sophisticated metagenomic analyses in the future, further illuminating the invisible microbial world that sustains planetary health and human wellbeing.

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing has revolutionized microbiome research by enabling comprehensive analysis of all genetic material within a sample, moving beyond the limitations of targeted 16S rRNA gene sequencing [31] [1]. This approach allows researchers to characterize thousands of organisms in parallel, providing unprecedented insights into community biodiversity and functional potential [1]. Unlike 16S sequencing, which targets a single phylogenetic marker gene, shotgun sequencing captures the entire genomic content, enabling species-level identification and functional profiling of microbial communities [31] [32]. The analysis of this complex data relies on several fundamental bioinformatics processes, including the reconstruction of Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs), binning, functional annotation, and taxonomic classification, which together form the foundation for interpreting microbial community structure and function.

Terminology Definitions and Applications

Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs)

Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) represent individual microbial genomes reconstructed from complex metagenomic sequencing data through computational methods [31]. This process bypasses the need for laboratory cultivation, which is particularly valuable since an estimated 1-2% of bacteria can be cultured using standard methods [32]. MAGs are binned into similar bacterial species or strains based on sequence similarity characteristics and coverage, providing insights into previously unculturable and unknown microorganisms [31]. The concept of MAGs has been further refined with the introduction of species-level genome bins (SGBs), which are categorized as known SGBs (kSGBs) for those present in reference databases and unknown SGBs (uSGBs) for newly-assembled genomes not previously cataloged [31]. MAGs enable strain-level analysis and the identification of specific microorganisms that play key roles in various biological processes, from human health to environmental ecosystems [33].

Binning

Binning is the computational process of grouping assembled DNA sequences (contigs) into biologically meaningful clusters that potentially represent individual microbial genomes or population-level genomes [31] [34]. This process typically relies on sequence composition (e.g., GC content, k-mer frequencies) and abundance patterns (coverage depth across multiple samples) to distinguish between different taxonomic origins [31]. Binning is essential for MAG reconstruction because metagenomic assembly produces contigs from all organisms in a community simultaneously without inherent taxonomic separation [34]. Advanced binning approaches now also incorporate taxonomic signals from longer sequences where available, first assigning contigs to MAGs and then associating reads with these longer sequences for more reliable taxonomic annotation [34]. Proper binning reduces data complexity and minimizes the generation of chimeric sequences where fragments from different genomes are incorrectly merged [32].

Functional Annotation

Functional annotation refers to the process of identifying putative biological functions of genes predicted from MAGs or assembled contigs based on information available in reference databases [35]. This process typically involves predicting genes in the assembled sequences and then comparing the protein sequences against reference databases to assign functional categories [35]. Current tools like DRAM perform comprehensive functional annotation using multiple databases including Pfam, KEGG, UniProt, CAZY, and MEROPS [35]. Functional annotation enables researchers to decipher the metabolic capabilities of microbial communities, identifying functions such as KEGG orthology groups, carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes), and antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) [24]. These annotations form the basis for downstream analyses including functional gene enrichment studies and the distillation of genome-inferred functional traits [35].

Taxonomic Classification

Taxonomic classification in metagenomics involves assigning taxonomic labels (e.g., phylum, genus, species) to sequencing reads, contigs, or MAGs based on their similarity to reference sequences [31] [34]. This process can utilize different approaches including marker gene methods (e.g., MetaPhlAn which uses species-specific marker genes), k-mer based classification (e.g., Kraken2), and homology searches against comprehensive protein databases (e.g., DIAMOND) [31] [34]. Unlike 16S rRNA sequencing, which provides phylogenetic information based on a single gene, shotgun metagenomic taxonomic classification leverages information from across the entire genome, providing significantly improved species-level resolution [31] [36]. Accurate taxonomic classification is essential for understanding microbial community composition and dynamics, with applications ranging from clinical diagnostics to environmental monitoring [36].

Quantitative Performance of Metagenomic Tools

Table 1: Performance comparison of taxonomic profiling tools based on benchmarking studies

| Tool | Classification Approach | Key Strengths | Reported Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| MetaPhlAn4 | Marker gene + MAG-based [31] | Well-established, commonly used [31] | Best overall performance in accuracy metrics [31] |

| Meteor2 | Microbial gene catalogues [24] | Excellent for low-abundance species [24] | 45% higher species detection sensitivity in shallow-sequenced data; 35% improved abundance estimation accuracy [24] |

| JAMS | k-mer based (Kraken2) + assembly [31] | High sensitivity [31] | Among highest sensitivity metrics [31] |

| WGSA2 | k-mer based (Kraken2) [31] | High sensitivity [31] | Among highest sensitivity metrics [31] |

| RAT | Integrated MAG/contig/read signals [34] | High precision and sensitivity [34] | Outperforms other tools in precision and sensitivity [34] |

Table 2: Functional annotation databases and their applications

| Database | Primary Focus | Utility in Metagenomics |

|---|---|---|

| KEGG | Metabolic pathways and ortholog groups [35] [24] | Functional orthologs and pathway analysis [24] |

| CAZy | Carbohydrate-active enzymes [24] | Carbohydrate metabolism and degradation [24] |

| MEROPS | Proteolytic enzymes [35] | Protein degradation and peptide metabolism [35] |

| Pfam | Protein families and domains [35] | Protein family classification and domain analysis [35] |

| Resfinder | Antibiotic resistance genes [24] | Identification of clinically relevant ARGs [24] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Taxonomic Profiling Using Integrated MAG and Read Signals

Principle: This protocol leverages the RAT (Read Annotation Tool) pipeline to integrate robust taxonomic signals from MAGs and contigs with direct read annotations for comprehensive taxonomic profiling [34].

Procedure:

- Assembly and Binning: Perform de novo assembly of quality-filtered reads using an assembler such as MEGAHIT or metaSPAdes [34]. Bin resulting contigs into MAGs using binning tools like MetaBAT2 or MaxBin [34].

- Contig and MAG Annotation: Annotate contigs and MAGs with CAT (Contig Annotation Tool) and BAT (Bin Annotation Tool) [34]:

- Predict Open Reading Frames (ORFs) on contigs and MAGs using Prodigal [34].

- Query predicted protein sequences against a reference protein database (NCBI nr or GTDB) using DIAMOND blastp [34].

- Assign taxonomy based on the combined taxonomic signals of individual ORFs, selecting higher-ranking taxa when conflicting signals are present [34].

- Read Mapping and Inheritance: Map individual reads to contigs using BWA-MEM, allowing each read to inherit the taxonomic annotation with the highest reliability (MAG annotation for binned contigs, contig annotation for unbinned contigs) [34].

- Direct Read Annotation: For sequences not mapping to contigs or without CAT annotation, perform direct annotation by querying against the protein database with DIAMOND blastx [34].

- Profile Reconstruction: Generate the final taxonomic profile by combining annotations from all steps, prioritizing the most reliable signals first [34].

Protocol 2: Functional Annotation of MAGs Using DRAM

Principle: This protocol uses the DRAM tool to perform comprehensive functional annotation of MAGs, integrating multiple reference databases to assign biological functions to predicted genes [35].

Procedure:

- Gene Prediction: Identify protein-coding genes in MAGs using ab initio gene prediction tools. Gene prediction is typically performed as part of the DRAM pipeline [35].

- Database Searching: Query predicted protein sequences against multiple functional databases simultaneously:

- Annotation Integration: Consolidate results from all databases, resolving conflicting annotations based on statistical confidence metrics and database priority rules established in the DRAM pipeline [35].

- Functional Profiling: Generate a functional profile for each MAG, categorizing genes into metabolic pathways, functional modules, and specific enzyme classes to enable comparative analysis across samples [35].

Protocol 3: Strain-Level Profiling with Meteor2

Principle: This protocol utilizes Meteor2 for strain-level analysis by tracking single nucleotide variants (SNVs) in signature genes of Metagenomic Species Pan-genomes (MSPs) [24].

Procedure:

- Read Mapping: Map quality-trimmed metagenomic reads against a microbial gene catalogue using bowtie2 with alignment parameters set to 95% identity for default mode or more stringent 98% identity for fast mode [24].

- Gene Quantification: Calculate gene counts using one of three computation modes:

- Taxonomic Profiling: Normalize gene count tables and reduce to generate MSP profiles by averaging the abundance of signature genes within each MSP after normalization [24].

- Strain Tracking: Identify strain-level variation by tracking SNVs in the signature genes of MSPs, enabling high-resolution analysis of microbial community dynamics [24].

Workflow Visualization

Shotgun Metagenomics Workflow

MAG Reconstruction & Annotation

Functional Annotation Process

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential research reagents and computational tools for shotgun metagenomics

| Category | Specific Products/Tools | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | MoBIO DNA Extraction Kit, Qiagen DNA Microbiome Kit, Epicentre Metagenomic DNA Isolation Kit [32] | Isolation of high-quality microbial DNA from complex environmental samples; critical for minimizing bias in microbial diversity assessment [32] |

| Library Preparation | Bioo Scientific NEXTflex PCR-Free, Illumina TruSeq PCR-Free, Kapa Hyper Prep Kit [32] | Preparation of sequencing libraries; PCR-free methods recommended to avoid amplification biases when sufficient DNA is available [32] |

| Taxonomic Profilers | MetaPhlAn4, RAT, JAMS, WGSA2, Meteor2 [31] [24] [34] | Assignment of taxonomic labels to reads, contigs, or MAGs; tools vary in approach (marker gene, k-mer, alignment-based) and performance characteristics [31] |

| Functional Annotation Tools | DRAM, Meteor2, HUMAnN3 [35] [24] | Prediction and categorization of gene functions using reference databases; enables metabolic reconstruction and functional potential assessment [35] |

| Reference Databases | KEGG, CAZy, Pfam, MEROPS, GTDB, NCBI nr [35] [24] [34] | Collections of curated biological information used for taxonomic assignment and functional annotation; database selection influences results interpretation [35] |

| DBCO-PEG5-NHS ester | DBCO-PEG5-NHS ester, MF:C36H43N3O11, MW:693.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Decafentin | Decafentin, CAS:15652-38-7, MF:C46H51BrClPSn, MW:868.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

From Sample to Insight: Methodological Workflows and Pharmaceutical Applications

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing is a powerful, high-throughput genomic technology that enables researchers to directly access the genetic content of entire microbial communities from complex samples without the need for cultivation [37]. This approach allows for the comprehensive sampling of all genes in all organisms present, providing unparalleled insights into microbial diversity, community structure, and functional potential [1]. Unlike targeted methods such as 16S rRNA sequencing, shotgun metagenomics captures data from all genomic domains—including bacteria, fungi, viruses, and archaea—while also enabling the reconstruction of metabolic pathways and the discovery of novel genes [37] [38]. This methodological framework is particularly valuable for microbiome functional analysis research, as it facilitates a systems-level understanding of how microbial communities operate and interact within their environments, from the human gut to various ecological niches.

Experimental Design and Sample Collection

The initial phase of any successful shotgun metagenomics study involves careful experimental design and sample collection, as these steps fundamentally influence all subsequent analyses. Sample processing represents the first and most critical step, where the goal is to obtain DNA that is representative of all cells present in the sample while ensuring sufficient quantities of high-quality nucleic acids for library production and sequencing [37].

Table 1: Sample Collection and Processing Considerations for Different Sample Types

| Sample Type | Key Considerations | Recommended Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Stool | Standardized collection; stable DNA | Commercial kits; homogenization |

| Skin (Low-Biomass) | High host contamination; minimal microbial DNA | D-Squame discs; in-house DNA extraction protocols [38] |

| Soil | Coextraction of enzymatic inhibitors (e.g., humic acids) | Physical separation of cells from soil matrix; benchmarked extraction procedures [37] |

| Host-Associated | Overwhelming host DNA | Fractionation or selective lysis to minimize host DNA [37] |

For low-biomass samples like skin swabs, specific collection methods such as D-Squame discs have proven most effective for maximizing DNA yields [38]. When dealing with samples containing inhibitory substances, physical separation of cells from the matrix (e.g., soil) before lysis can reduce coextraction of contaminants that interfere with downstream processing [37]. For host-associated microbiomes, fractionation or selective lysis methods are crucial to minimize host DNA contamination, which could otherwise overwhelm the microbial signal in sequencing data [37].

DNA Extraction and Quality Control

DNA extraction represents a potential source of significant bias in metagenomic studies, as different protocols can vary considerably in their efficiency across diverse microbial taxa. The extraction method must be carefully selected to ensure representative lysis of all cell types present in the community while yielding DNA of sufficient quantity and quality for library preparation.

Multiple studies have demonstrated that direct lysis of cells within the sample matrix versus indirect lysis after cell separation produces quantifiable differences in microbial diversity, DNA yield, and sequence fragment length [37]. For low-biomass samples like skin microbiomes, research indicates that specialized in-house DNA extraction protocols often outperform standardized kits when it comes to maximizing microbial DNA yields [38]. A critical finding from recent work is that Multiple Displacement Amplification (MDA), while capable of amplifying femtograms of DNA to micrograms of product, introduces significant compositional biases and is not recommended for metagenomic applications where accurate representation of community structure is essential [37] [38].

For samples yielding very small amounts of DNA, amplification might be necessary, but researchers should be aware of potential problems including reagent contamination, chimera formation, and sequence bias, all of which can significantly impact subsequent metagenomic community analysis [37]. Quality control assessment of extracted DNA typically involves fluorometric quantification, fragment analysis, and purity assessment via spectrophotometric methods to ensure the material is suitable for library construction.

Library Preparation and Sequencing Technologies

Library preparation converts the extracted DNA into a format compatible with sequencing platforms, with specific protocols varying based on the technology employed. This process typically involves DNA fragmentation, size selection, adapter ligation, and potentially amplification steps. The choice of sequencing technology represents a critical decision point that balances read length, accuracy, throughput, and cost considerations for metagenomic applications.

Table 2: Comparison of Sequencing Technologies for Metagenomics

| Technology | Read Length | Key Features | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short-Read (Illumina) | 150-300 bp (paired-end) | High accuracy; very high throughput; low cost per Gb [37] [1] | Taxonomic profiling; gene abundance studies; large-scale comparative analyses |

| Long-Read (PacBio HiFi) | Several kilobases | High accuracy long reads; excellent for assembly [33] | Metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs); resolving complex genomic regions |