The Gut Microbiome in Health and Disease: From Mechanistic Insights to Next-Generation Therapeutics

This article synthesizes current research on the gut microbiome's role in human health and disease, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

The Gut Microbiome in Health and Disease: From Mechanistic Insights to Next-Generation Therapeutics

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on the gut microbiome's role in human health and disease, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers foundational concepts of microbiome composition and host interactions, explores advanced methodologies like multi-omics and gnotobiotic models for target identification, and analyzes challenges in translating research into therapies. The scope includes troubleshooting dysbiosis, optimizing microbial manipulation via FMT, next-generation probiotics, and phages, and validating approaches through comparative analysis of clinical trials and emerging trends in precision microbiome medicine.

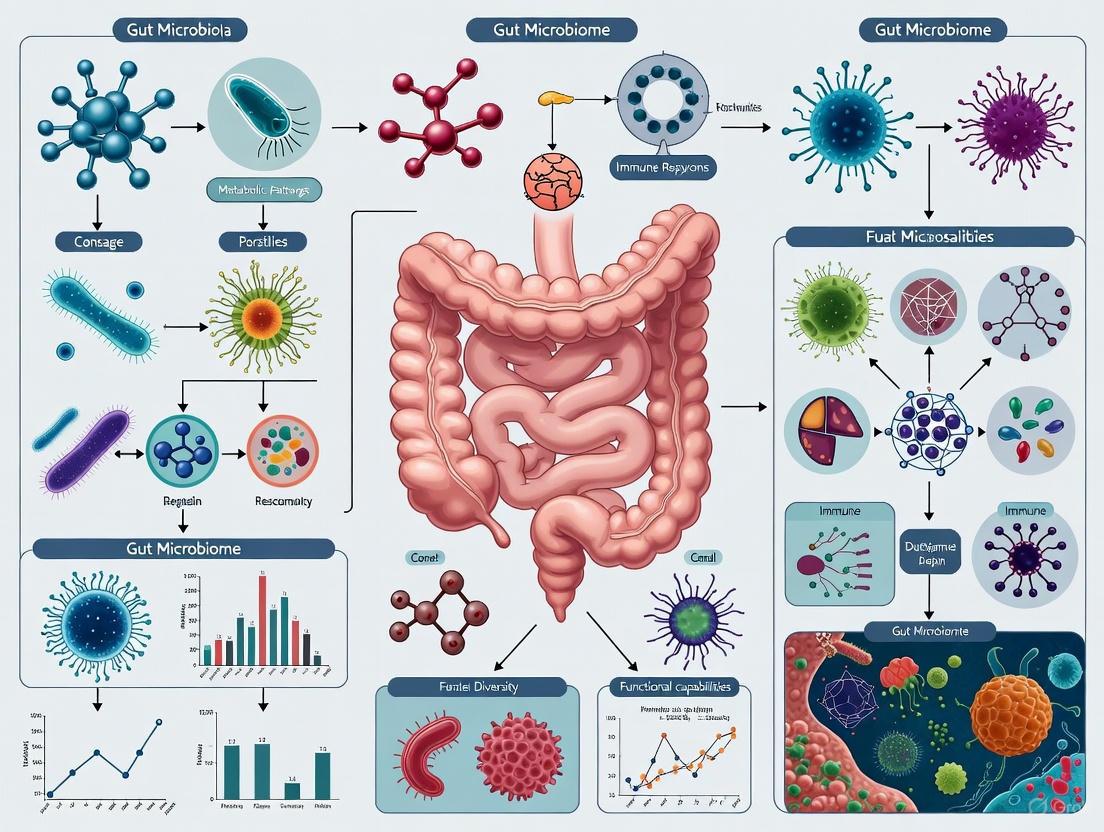

Defining the Ecosystem: Core Concepts of the Gut Microbiome and Its Role in Human Physiology

In the rapidly advancing field of microbial research, the terms "microbiota" and "microbiome" are frequently used, yet they represent distinct concepts with critical differences that are essential for precise scientific communication. While both concepts revolve around microbial communities, their definitions encompass different scopes and components. Understanding this distinction is particularly crucial in gut health and disease association research, where the composition and function of microbial communities can significantly influence host physiology, disease states, and therapeutic responses [1] [2].

The confusion between these terms often stems from their historical usage and the overlapping nature of their referents. However, as research methodologies have advanced, particularly with the development of high-throughput sequencing technologies, the scientific community has developed more precise definitions that recognize the functional and genetic dimensions beyond mere taxonomic classification [1]. This semantic precision becomes increasingly important as we seek to understand the complex mechanisms through which microbial communities influence human health and disease.

Table 1: Core Definitions in Microbial Research

| Term | Definition | Key Components | Scope |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microbiota | The community of microorganisms themselves found in a specific environment [1] [2]. | Bacteria, archaea, fungi, viruses, and other microbes [3]. | Limited to the microorganisms themselves and their relative abundances. |

| Microbiome | The entire habitat, including microorganisms, their genetic elements, and environmental conditions [1] [2]. | Microbiota, their structural elements, metabolites, genetic material, and surrounding environmental conditions [1] [2]. | Encompasses the entire ecological system, including functional potential. |

The relationship between microbiota and microbiome is hierarchical and inclusive. The microbiome represents the broader ecological context, while the microbiota constitutes one component within this system. To extend the analogy presented by Allucent et al., if the microbiome is a house, the microbiota represents the people living there, while the furniture and other contents represent the genetic material, metabolites, and environmental factors that complete the system [1]. This distinction becomes methodologically significant when designing studies, as investigating the microbiota primarily involves taxonomic characterization, while studying the microbiome requires additional analysis of functional potential, genetic elements, and environmental interactions.

Key Components and Analytical Framework

Expanding the Vocabulary: Related Terminology

Beyond the core definitions of microbiota and microbiome, several related terms complete the analytical framework used in microbial research. These terms allow researchers to describe specific aspects of microbial communities and their study with greater precision, which is particularly valuable when communicating methodological approaches and findings in scientific literature.

Metagenome refers to the collection of genes and genomes from the microbiota in a given environment [1]. This concept represents the genetic complement of the microbiota and is identified through DNA extraction and metagenomic sequencing. The analysis of the metagenome helps researchers understand the functional capabilities of a microbial community, potentially explaining how specific microbiota function in health and disease states. Unlike the broader microbiome concept, the metagenome specifically focuses on the genetic material present, excluding the immediate environmental conditions and interactions that the microbiome encompasses.

The term microflora represents an older concept that has been largely superseded in rigorous scientific literature. Traditionally, this term referred primarily to microscopic plants, though its definition was later expanded to include various bacteria and microorganisms found in environments such as the human intestinal tract [1]. However, this term lacks the specificity required for modern medical and scientific literature, and its use is now generally confined to popular science rather than technical research communications.

Visualizing the Relationship Between Core Concepts

The following diagram illustrates the hierarchical relationship between the key terms discussed, clarifying how they interrelate within a research context:

The Research Context: Gut Microbiome in Health and Disease

In gut health and disease research, distinguishing between microbiota and microbiome has practical implications for study design and interpretation. Research focused on microbiota typically characterizes which microorganisms are present, their relative abundances, and how these compositions differ between health and disease states [2] [4]. For example, numerous studies have identified reduced microbial diversity in many diseases, with significant alterations in microbial communities detected across most conditions examined [4].

In contrast, research addressing the microbiome investigates not only which microbes are present but also their functional potential, genetic interactions, metabolite production, and relationship with the host environment [2]. This broader approach can reveal mechanisms behind observed associations, such as how microbial-derived metabolites influence host physiology or how environmental factors shape microbial community structure and function.

The gut microbiome functions as a crucial interface between host genetics, environmental exposures, and health outcomes. In healthy states, gut microbiota contribute to numerous physiological processes including nutrient extraction, metabolism, immune modulation, and protection against pathogens through colonization resistance [2]. However, when dysbiosis occurs—an imbalance in the microbial community—this can contribute to disease pathogenesis through multiple mechanisms including immune dysregulation, induction of chronic inflammation, and altered metabolic outputs [2].

Methodological Approaches in Microbiome Research

Experimental Workflow for Gut Microbiome Analysis

Investigating the gut microbiome requires a multi-step process that transforms biological samples into interpretable data. The following diagram outlines a generalized experimental workflow, from sample collection through data analysis:

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Conducting robust microbiome research requires specific reagents and computational tools that enable precise characterization of microbial communities. The selection of these resources can significantly influence results, particularly due to methodological variations between studies [5]. The following table outlines key solutions used in typical gut microbiome studies:

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Gut Microbiome Analysis

| Item | Function in Research | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA Gene Primers | Amplify variable regions for bacterial identification and classification [5]. | Selection of hypervariable region (V1-V9) introduces bias; affects taxonomic resolution and community profile [5]. |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Lyse microbial cells and purify genetic material for downstream analysis [5]. | Lysis efficiency varies for different bacterial taxa; influences observed community structure [5]. |

| Sequencing Platforms (Illumina, Ion Torrent) | Determine nucleotide sequences of amplified genes or entire genomes [5]. | Different technologies (e.g., Illumina vs. Ion Torrent) impact read length, error profiles, and cost [5]. |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines (QIIME 2, mothur, MetaPhlAn4) | Process raw sequence data into taxonomic and functional profiles [5] [4]. | Choice of reference database and algorithm affects taxonomic assignment accuracy and resolution [4]. |

| Reference Databases (Greengenes, SILVA, GTDB) | Provide curated taxonomic frameworks for classifying sequence data [5]. | Database composition and curation influence which taxa can be identified and at what resolution. |

Methodological Considerations in Study Design

The methodological variability in microbiome research presents significant challenges for comparing results across studies. Differences in sample collection, DNA extraction methods, choice of 16S rRNA hypervariable regions, sequencing platforms, and bioinformatic processing can all substantially influence the resulting microbial community profiles [5]. For example, the selection of which hypervariable region to amplify introduces specific biases in the taxonomic composition observed, as different primer sets have varying amplification efficiencies across bacterial taxa [5].

Recognizing these methodological challenges, large-scale initiatives such as the Human Microbiome Project (HMP) by the National Institutes of Health have worked to establish standardized protocols and reference datasets [1]. These resources provide benchmark data that facilitate more consistent approaches across the research community. Furthermore, methods such as shotgun metagenomic sequencing—which sequences all DNA in a sample rather than just specific marker genes—can provide a more comprehensive view of the microbiome, including functional potential through analysis of microbial genes and pathways [4].

Applications in Disease Research and Therapeutic Development

Microbiome Signatures Across Diseases

Large-scale analyses of gut microbiome studies have revealed consistent patterns of alteration in various disease states. A 2024 meta-analysis of 6,314 fecal metagenomes from 36 case-control studies identified significant shifts in microbial diversity and composition across multiple diseases [4]. The research detected 277 disease-associated gut species, including numerous opportunistic pathogens enriched in patients and a concurrent depletion of beneficial microbes [4].

Table 3: Microbial Diversity Changes in Selected Diseases

| Disease Category | Specific Condition | Change in Species Richness | Change in Shannon Diversity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory Bowel Disease | Crohn's Disease | Decrease (>10%) | Decrease (>10%) | [4] |

| Infectious Diseases | COVID-19 | Decrease (>10%) | Decrease (>10%) | [4] |

| Cardiometabolic | Hypertension | Decrease (>10%) | Decrease (>10%) | [4] |

| Neurological | Parkinson's Disease | Increase | Increase | [4] |

| Autoimmune | Systemic Lupus Erythematosus | Decrease (>10%) | Decrease (>10%) | [4] |

These disease-associated microbiome signatures have demonstrated potential diagnostic value. A random forest classifier based on these microbial signatures achieved high accuracy in distinguishing diseased individuals from controls (AUC = 0.776) and high-risk patients from controls (AUC = 0.825), maintaining performance in external validation cohorts [4]. This suggests that despite methodological variations between studies, consistent and generalizable microbiome patterns exist across populations and disease states.

Microbiota-Targeted Therapeutic Approaches

Understanding the distinction between microbiota and microbiome directly informs therapeutic development. While microbiota-focused interventions aim to modify the composition of microbial communities themselves, microbiome-targeted approaches consider the broader ecological context, including functional genes and environmental conditions.

Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) represents a primarily microbiota-focused intervention that transfers entire microbial communities from healthy donors to patients. This approach has demonstrated remarkable efficacy in treating recurrent Clostridioides difficile infections, effectively restoring a healthy microbial community structure [2].

More targeted approaches include:

- Probiotics: Specific live microorganisms that confer health benefits when administered in adequate amounts [6].

- Prebiotics: Substrates selectively utilized by host microorganisms that confer health benefits [6].

- Postbiotics: Preparations of inanimate microorganisms and/or their components that confer health benefits [6].

Recent research has also explored how medications beyond antibiotics affect the gut microbiome. A 2025 Stanford study investigated how 707 different drugs impact gut microbial communities, finding that 141 medications significantly altered microbiome composition [7]. The research revealed that competition for nutrients plays a significant role in determining which bacteria thrive or diminish following medication treatment, providing predictable ecological rules that could inform future drug design to minimize detrimental effects on gut microbial communities [7].

The distinction between microbiota as the community of microorganisms themselves and microbiome as the comprehensive habitat including genetic elements and environmental conditions is fundamental to rigorous research in the field. This precision in terminology becomes increasingly critical as we advance our understanding of how microbial communities influence human health and disease. For researchers investigating gut microbiome health and disease associations, recognizing this distinction informs study design, methodology selection, and data interpretation.

The expanding toolbox for microbiome research—from standardized analytical protocols to advanced computational models—enables increasingly sophisticated investigations into the mechanisms linking microbial communities to health outcomes. Furthermore, the identification of consistent microbial signatures across diverse diseases suggests potential pathways for developing microbiome-based diagnostics and therapeutics. As the field continues to evolve, maintaining clear conceptual distinctions between microbiota and microbiome will facilitate more precise communication and more effective translation of research findings into clinical applications.

The human gut microbiome undergoes a precise sequence of colonization and succession from birth through adulthood, a process fundamentally important to lifelong health. This developmental trajectory is characterized by predictable shifts in microbial diversity, composition, and functional capacity. The establishment of this microbial ecosystem within the first years of life is now understood to be a critical determinant in programming the host's immune, metabolic, and neurological systems [8] [9]. Disruptions during this period, termed the "critical window of development," can induce microbial dysbiosis, which is increasingly implicated in the pathogenesis of a wide array of diseases within the framework of the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) [8]. This whitepaper delineates the stages of gut microbiome maturation, the factors influencing its assembly, the underlying molecular mechanisms, and the experimental methodologies essential for its investigation, providing a scientific foundation for therapeutic interventions targeting the gut microbiome.

The Phased Succession of the Gut Microbiome

The maturation of the gut microbiome is not a linear process but occurs through distinct, overlapping phases characterized by specific taxonomic and functional profiles. The plasticity of the microbiome is highest during the initial stages, gradually stabilizing into an adult-like state.

Developmental Stages and Taxonomic Shifts

The progression from infancy to early childhood marks a period of rapid microbial evolution. The gut microbiome reaches a mature, stable composition resembling that of an adult around 2.5 to 3 years of age, though some studies suggest the process may extend further [10] [9]. This progression can be categorized into three primary stages:

- Developmental Stage (3–14 months): This phase is dominated by Bifidobacterium [10]. The gut microbiota of infants is initially composed of facultative anaerobes (e.g., Enterobacterales, Enterococci, Staphylococci), which consume oxygen and create an environment conducive for obligate anaerobes [11].

- Transitional Stage (15–30 months): Characterized by an increase in microbial diversity, this stage sees a rise in Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes, coinciding with the introduction of solid foods [10].

- Stability Stage (≥31 months): The microbiome stabilizes with Firmicutes becoming the predominant phylum, and the community structure begins to resemble that of an adult [10].

The table below summarizes the relative abundance of major bacterial phyla and genera during key developmental periods, synthesized from systematic reviews and cohort studies [12] [10] [9].

Table 1: Taxonomic Shifts in the Developing Gut Microbiome

| Life Stage | Dominant Phyla (Relative Abundance) | Dominant Genera | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infancy (0-12 months) | Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria | Bifidobacterium, Bacteroides, Escherichia, Lactobacillus, Staphylococcus | Low diversity, high volatility; strongly influenced by diet (breastmilk vs. formula) and delivery mode. |

| Preadolescence (2-12 years) | Firmicutes (~51%), Bacteroidetes (~36%), others | Bacteroides (~16%), Prevotella (~9%), Faecalibacterium (~8%), Bifidobacterium (~5%) [12] | Achieves adult-like diversity and composition; influenced by geography and diet. |

| Adulthood | Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes | Faecalibacterium, Bacteroides, Prevotella, Ruminococcus | High diversity and stability; core microbiome established. |

| Old Age / Longevity | Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes | ↑ Akkermansia; ↓ Faecalibacterium, Bacteroidaceae, Lachnospiraceae [13] | Increased alpha diversity; distinct beta diversity from younger adults; potential inflammatory status. |

The Concept of the "Critical Window"

The first 1000 days of life—from conception to approximately two years of age—represent a critical window of development for the gut microbiome [10] [9]. During this period, the microbial ecosystem is highly plastic and susceptible to environmental influences. Once established, a significant portion (60-70%) of an individual's gut microbiome remains relatively constant throughout life [9]. This early-life microbiota is essential for the maturation of the immune system, and disruptions during this period can have long-lasting effects, predisposing individuals to various diseases such as asthma, allergies, obesity, and inflammatory bowel disease later in life [8] [14] [9]. This aligns with the DOHaD hypothesis, which posits that early-life environmental exposures can program an individual's risk for chronic diseases in adulthood [8].

Determinants of Microbial Assembly and Succession

The trajectory of gut microbiome colonization is shaped by a complex interplay of maternal, environmental, and medical factors. Understanding these determinants is crucial for identifying levers to manipulate the microbiome for therapeutic benefit.

Prenatal and Perinatal Factors

Contrary to the long-held belief of a sterile uterus, emerging evidence suggests that microbial exposure may begin in utero, with bacteria detected in the placenta, amniotic fluid, and meconium [11] [10]. However, the most significant microbial inoculation occurs at birth.

- Mode of Delivery: Vaginally delivered infants acquire microbes resembling their mother's vaginal microbiota (e.g., Lactobacillus, Prevotella). In contrast, cesarean-delivered infants are initially colonized by microbes from the maternal skin and hospital environment (e.g., Staphylococcus, Corynebacterium, Propionibacterium), and exhibit lower levels of Bifidobacterium and Bacteroides [10].

- Maternal Factors: The maternal gut, oral, and vaginal microbiota, which undergo changes during pregnancy, serve as primary sources for the infant's microbiome [8] [11]. Maternal diet, BMI, antibiotic use during pregnancy, and overall health status can significantly alter these microbial reservoirs, thereby influencing the infant's microbial inheritance [8] [10].

Postnatal Factors

Following birth, diet becomes the most influential factor driving microbial succession.

- Feeding Type: Breastfed infants have a gut microbiome dominated by Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus, due to the presence of human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs) that selectively promote their growth. Formula-fed infants, meanwhile, exhibit a more diverse microbiome with higher levels of Bacteroides, Clostridia, Staphylococci, and Enterococci [10].

- Antibiotic Exposure: Antibiotic use, particularly intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP), has a profound and sustained impact. A 2025 study found that IAP-exposed infants had a significantly lower relative abundance of Bifidobacterium longum at one month of age, an effect that persisted at one year. This was coupled with a pro-inflammatory T-helper cell profile [15]. Beyond antibiotics, other common medications can also unsettle the gut microbiome by triggering nutrient competition among gut bacteria [7].

- Introduction of Solid Foods: The weaning process catalyzes a major shift in the gut microbiome, driving an increase in diversity and a transition toward an adult-like profile dominated by Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes [10].

Table 2: Impact of Early-Life Factors on Gut Microbiome Composition

| Factor | Impact on Microbial Diversity | Impact on Key Taxa | Associated Long-Term Health Risks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cesarean Section | Reduced initial diversity | ↑ Staphylococcus, Corynebacterium; ↓ Bifidobacterium, Bacteroides [10] | Increased risk of asthma, allergies, and obesity [8] [9] |

| Formula Feeding | Alters trajectory, often increases diversity early on | ↑ Bacteroides, Clostridia, Staphylococci; ↓ Bifidobacterium [10] | Modulated risk of atopic diseases and obesity |

| Antibiotic Exposure | Can reduce diversity, with effects lasting years | ↓ Bifidobacterium, Bacteroides; ↑ Proteobacteria [15] [8] | Asthma, eczema, allergic diseases, obesity [15] [8] |

| Maternal Obesity | Alters inherited microbiota | ↑ Bacteroides, Staphylococcus; ↓ Bifidobacterium [8] | Predisposition to obesity and metabolic disorders [8] |

Molecular Mechanisms and Host-Microbe Interactions

The developing gut microbiome exerts its long-term effects on host health through complex molecular crosstalk, primarily mediated by microbial metabolites and immune system education.

Key Signaling Pathways and Metabolites

- Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs): Produced by bacterial fermentation of dietary fiber, SCFAs (acetate, propionate, butyrate) are crucial for gut health. They serve as energy sources for colonocytes, strengthen the gut epithelial barrier, and exert potent immunomodulatory effects. Butyrate, for instance, promotes the differentiation of regulatory T cells (Tregs), which are essential for maintaining immune tolerance and preventing aberrant inflammation [12] [9]. SCFAs signal through G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) like GPR41, GPR43, and GPR109a, which are expressed on various immune and epithelial cells [9].

- Gut-Brain Axis Communication: The gut microbiome bidirectionally communicates with the brain through the vagus nerve, the production of neurotransmitters (e.g., GABA, serotonin), and microbial metabolites like SCFAs [9]. This axis is critical for neurodevelopment, and dysbiosis in early life has been linked to neurodevelopmental disorders [9].

- T-helper Cell Balance: The gut microbiome plays a critical role in educating the immune system and balancing T-helper cell populations. As demonstrated in the IAP study, microbial disruption can lead to a pro-inflammatory state characterized by higher levels of IL-17A, RORγt, and TGF-β, indicative of a Th17-skewed response [15]. This highlights the microbiome's role in regulating the Treg/Th17 balance, which is crucial for immune homeostasis [15].

The following diagram illustrates the primary mechanisms by which the early-life gut microbiome communicates with and influences distant organ systems.

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Research into the developing gut microbiome relies on a suite of sophisticated technologies for profiling microbial communities and modeling their interactions with the host.

Core Profiling Technologies

- 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing: This is the most widely used method for profiling microbial community composition. It involves amplifying and sequencing hypervariable regions of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene. The choice of hypervariable region (e.g., V3-V4, V4) can influence the taxonomic resolution and results, making standardization important for cross-study comparisons [15] [12].

- Shotgun Metagenomics: This technique sequences all the genetic material in a sample, providing not only taxonomic information at a higher resolution than 16S sequencing but also insights into the functional potential of the microbial community [13].

- Metabolomics: Liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (LC-MS) is used to profile the metabolome, including microbial metabolites like SCFAs, bile acids, and neurotransmitters. This provides a direct readout of microbial functional output [13].

The typical workflow for a microbiome study, from sample collection to data interpretation, is outlined below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Technologies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Gut Microbiome Studies

| Item | Function / Application | Example Protocols / Kits |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality microbial DNA from complex stool samples for downstream sequencing. | DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (Qiagen) [15] |

| 16S rRNA Primers | Amplification of specific hypervariable regions for taxonomic profiling. | Primers for V3/V4 regions [15] |

| MiSeq Reagent Kit | Sequencing of amplicon libraries on the Illumina platform. | MiSeq Reagent Kit V3 (600 cycles) [15] |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies | Immunophenotyping of host immune cells to correlate with microbial changes. | Antibodies for CD3, CD4, CD25, Foxp3, IL-17A, RORγt [15] |

| CapScan Device | A novel, ingestible capsule for sampling the microbiome of the small intestine, a previously difficult-to-access site [16]. | CapScan capsule [16] |

| Live Biotherapeutic Products (LBPs) | Defined bacterial consortia investigated as therapeutics to restore a healthy gut microbiome. | EBX-102-02 (for IBS-C), purified Firmicutes spores (for rCDI) [16] |

| tetranor-PGDM | tetranor-PGDM, CAS:70803-91-7, MF:C16H24O7, MW:328.36 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Toltrazuril-d3 | Toltrazuril-d3, CAS:1353867-75-0, MF:C18H14F3N3O4S, MW:428.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Models for Mechanistic Insight

- Gnotobiotic Models: Germ-free mice, colonized with defined human microbial communities, are a gold-standard model for establishing causal relationships between the microbiome and host phenotype. They are indispensable for studying the functional impact of specific microbes or communities.

- In Vitro Culturing Systems: Advanced culturing of complex microbial communities derived from human fecal samples allows for systematic testing of pharmaceutical compounds or dietary interventions. A Stanford study used this approach to test 707 different drugs, finding that 141 altered the microbiome, primarily through nutrient competition [7].

- Longitudinal Cohort Studies: Human studies that track infants and children over time are critical for defining the normal trajectory of microbiome development and understanding how perturbations correlate with health outcomes. These studies require careful collection of metadata, including diet, medication use, and health records [15] [8].

The development of the gut microbiome from infancy to adulthood is a meticulously orchestrated process of colonization and succession, pivotal for setting the trajectory of lifelong health. The "critical window" of early life represents a period of unparalleled plasticity, during which factors like delivery mode, diet, and antibiotic exposure can permanently shape the microbial ecosystem and, consequently, the host's immune and metabolic programming. Disruptions to this process are mechanistically linked to disease via altered microbial metabolites, immune dysregulation, and cross-talk with distant organs. Future research and therapeutic development will rely on sophisticated multi-omics approaches, advanced culturing technologies, and defined live biotherapeutics to precisely diagnose and correct dysbiosis, ultimately harnessing the microbiome to improve human health from its earliest foundations.

The human gastrointestinal (GI) tract hosts one of the most complex microbial ecosystems, with its composition and function critical to host health. A key characteristic of this system is its profound spatial heterogeneity; the microbial communities are not uniform but vary significantly across different segments [17]. Understanding this spatial distribution is fundamental to elucidating the gut microbiome's role in health and disease. While many studies rely on fecal samples as a proxy for the gut microbiota, this approach overlooks the compartmentalized nature of microbial communities along the GI tract [17]. This review synthesizes current knowledge on the spatial variation of the gut microbiota, detailing the distinct microbial compositions in different GI segments, the advanced methodologies used to study them, and the implications of this spatial organization for host physiology and disease pathogenesis.

Spatial Heterogeneity of the Gut Microbiome

The GI tract presents a series of diverse microenvironments, varying in pH, oxygen tension, nutrient availability, and host immune factors, which select for distinct microbial assemblages. A foundational study in wild house mice examining ten segments of the GI tract—oral cavity, esophagus, stomach, duodenum, ileum, proximal cecum, distal cecum, colon, rectum, and feces—clearly demonstrated this spatial stratification [17].

Upper vs. Lower GI Tract Dichotomy

The most pronounced difference in microbial composition exists between the upper and lower GI tract.

- Upper GI Tract: The stomach and small intestine are characterized by lower microbial diversity and a greater relative abundance of facultative anaerobes, which can tolerate the more oxygen-rich and dynamic environment [17].

- Lower GI Tract: The cecum and colon are characterized by a greater relative abundance of strict anaerobic bacteria (e.g., from the phyla Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes) and significantly higher microbial diversity. This is the primary site for fermentation of dietary fibers into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate, acetate, and propionate [17].

Table 1: Microbial Composition and Function Across Major GI Segments

| GI Segment | Dominant Phyla/Genera | Environmental Conditions | Key Microbial Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stomach & Small Intestine | Lower diversity; Facultative anaerobes (e.g., Lactobacillus, Enterobacteriaceae) | Lower pH (stomach), rapid transit, higher oxygen | Nutrient absorption; initial digestion; immune sampling |

| Cecum & Colon | High diversity; Strict anaerobes (e.g., Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, Faecalibacterium, Akkermansia) | Neutral pH, slow transit, anaerobic | Fermentation of dietary fiber; production of SCFAs; vitamin synthesis; immune regulation |

Beyond this broad dichotomy, significant variation exists within the lower tract. For instance, the proximal and distal halves of the cecum can harbor different microbial communities [17]. Furthermore, microbial communities derived from fecal samples, while similar to those in the lower GI tract, are not identical to colonic communities, highlighting the need for caution when extrapolating from fecal data alone [17].

Individual Host Factors

While gut segment is a primary driver of microbial composition, variation among individual hosts also plays a significant role. Even when considering the upper and lower GI tracts separately, microbial composition has been shown to associate with individual mice, suggesting that diet, host genotype, and habitat contribute to the spatial structuring of these communities [17].

Advanced Methodologies for Spatial Microbiome Analysis

Traditional 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing, as used in the mouse study above, has laid the groundwork for understanding microbial composition [17]. However, emerging "enhanced metagenomic strategies" are providing unprecedented resolution.

Next-Generation Sequencing and Multi-Omics

- Long-Read Sequencing: Technologies like Oxford Nanopore and PacBio resolve repetitive genomic elements and structural variations, enabling complete genome assembly from complex samples and improving the study of mobile genetic elements like plasmids [18].

- Single-Cell Metagenomics: This approach bypasses cultivation biases by isolating individual microbial cells, revealing the genomic blueprints of uncultured taxa and providing insights into functional heterogeneity [18].

- Multi-Omics Integration: Combining metagenomics with metatranscriptomics, metaproteomics, and metabolomics shifts the focus from "who is there" to "what they are doing," mapping niche-specific activities and host-microbe communication [18].

Computational and Modeling Tools

- AI-Guided Annotation: Machine learning and advanced bioinformatics are used to annotate microbial genes and pathways with high accuracy, reducing functional inference biases [18].

- Genome-Scale Models (ME-models): Innovative tools like coralME rapidly create detailed genome-scale computer models that link a microbe's genome to its phenotype. These models can simulate how gut bacteria respond to different nutrients and predict the formation of microbial metabolites, providing a mechanistic basis for understanding behavior in complex environments like the gut of patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) [19].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Gut Microbiome Spatial Analysis

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function and Application |

|---|---|

| 16S rRNA Gene Primers (e.g., 515F/806R) | Amplify the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene for taxonomic profiling of microbial communities [17]. |

| QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit | DNA extraction from complex gut content and mucosal samples, often with mechanical lysis enhancement [17]. |

| Greengenes Database | Reference database for clustering 16S rRNA sequences into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) and assigning taxonomy [17]. |

| PBS Buffer | Used for rinsing and homogenizing gut tissue samples to maintain osmotic balance and preserve microbial integrity during collection. |

| Zirconia/Silica Beads | Used in mechanical lysis via bead-beating to effectively break open hardy microbial cell walls for DNA extraction [17]. |

| coralME Software Tool | Generates Metabolism and Expression models (ME-models) from genomic data to predict microbial metabolic interactions and phenotypes [19]. |

Implications for Host Health and Disease

The spatial distribution of gut microbiota is not merely an ecological curiosity; it has direct consequences for host health through multiple axes of communication.

Signaling Pathways and Host-Microbe Interactions

Spatially specific microbial activities influence host physiology via key signaling pathways. Diagrammatically, the gut-liver axis communication can be summarized as follows:

Diagram 1: Gut-Liver Axis Pathways

Gut-Liver Axis: Altered microbial composition in the colon, such as an enrichment of Clostridium scindens, increases the production of secondary bile acids (e.g., deoxycholic acid). These disrupt the Farnesoid X receptor (FXR) signaling in the liver, impairing lipid/glucose metabolism and promoting steatosis. Concurrently, gut-derived endotoxins (e.g., LPS) can translocate via the portal circulation, activating inflammatory pathways and contributing to liver injury [18].

Gut-Brain Axis: This bidirectional communication network is mediated by microbial metabolites. Dysbiosis in the lower GI tract can reduce the production of SCFAs and serotonin precursors, while increasing pro-inflammatory mediators like TMAO. These shifts can exacerbate neuroinflammation, compromise blood-brain barrier integrity, and are implicated in conditions like anxiety, depression, and Alzheimer's disease [18].

Dysbiosis and Disease

Spatial dysbiosis—the disruption of microbial communities in their specific niches—is linked to disease. For example:

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): Blooms of Enterobacteriaceae in the ileal or colonic mucosa are associated with elevated IL-17 production and mucosal damage [18]. Models from coralME reveal that IBD patients exhibit shifts in gut chemistry, including elevated pH and decreased SCFA production [19].

- Colorectal Cancer (CRC): The mucosal-associated pathobiont Bacteroides fragilis can promote oncogenic Wnt/β-catenin signaling through polysaccharide A, driving disease progression [18].

The experimental workflow for establishing these spatial-disease relationships often follows a structured path, from sample collection to therapeutic insight:

Diagram 2: Spatial Dysbiosis Research Workflow

The microbial composition of the gastrointestinal tract is not homogenous but is instead a highly organized and spatially structured ecosystem. The stark contrast between the upper and lower GI tract, coupled with finer-scale variations within segments and the influence of individual host factors, underscores the complexity of this community. Advanced methodologies, from long-read sequencing to mechanistic computational models, are illuminating the functional consequences of this spatial distribution. Understanding how specific microbes in specific locations influence host pathways via axes like the gut-liver and gut-brain axes is crucial for moving from associative observations to causative mechanisms. This refined spatial perspective is paving the way for a new era of personalized microbiome-based diagnostics and therapies, allowing for targeted interventions that consider the ecological nuances of the human gut.

The human gut microbiome functions as a virtual endocrine organ, producing a diverse array of metabolites that profoundly influence host physiology and disease susceptibility. These microbial metabolites represent critical interfaces in host-microbiome crosstalk, mediating effects far beyond the gastrointestinal tract. Within the vast repertoire of microbial chemicals, short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), bile acids (BAs), and vitamins have emerged as particularly crucial functional mediators in health and disease. This review synthesizes current understanding of these key microbial metabolites, framing their roles within the broader context of gut microbiome-health-disease associations. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the mechanistic basis of these metabolites provides unprecedented opportunities for therapeutic intervention. The intricate metabolic interplay between host and microbiota not only maintains homeostasis but, when disrupted, contributes to pathogenesis across multiple organ systems, including cardiovascular, neurological, and hepatic diseases [20] [21]. This whitepaper provides a technical overview of these metabolites, their quantitative profiles, experimental approaches for their study, and their integration into current drug discovery paradigms.

Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs): Microbial Fermentation Products

Production, Metabolism, and Physiological Concentrations

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), primarily acetate (C2), propionate (C3), and butyrate (C4), are the main metabolites produced from microbial fermentation of dietary fibers and resistant starch in the colon. They are present in an approximate molar ratio of 60:20:20, with approximately 500-600 mmol produced daily in the human gut [22]. Their production is influenced by multiple factors including substrate source, gut microbiota composition, colonic pH, and transit time [23]. Following production, SCFAs are absorbed by colonocytes via monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs and SMCTs). Butyrate serves as a primary energy source for colonocytes, while acetate and propionate that escape hepatic metabolism enter systemic circulation to exert peripheral effects [23] [22].

Table 1: Major SCFAs: Sources, Concentrations, and Primary Functions

| SCFA Type | Primary Producing Bacteria | Typical Fecal Concentration (μM/g) | Major Physiological Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetate | Numerous commensals | Most abundant | Substrate for cholesterol synthesis; influences appetite regulation |

| Propionate | Bacteroidetes spp. | ~20-80 μM/g | Gluconeogenesis precursor; regulates satiety and immune function |

| Butyrate | Firmicutes (e.g., Faecalibacterium prausnitzii) | ~20-50 μM/g | Primary colonocyte energy source; anti-inflammatory; maintains gut barrier |

Mechanisms of Action and Host Benefits

SCFAs influence host physiology through multiple mechanisms, primarily via G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) activation (e.g., GPR41, GPR43, GPR109a) and histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibition [23] [22]. The health benefits of SCFAs are extensive and well-documented:

- Immunoregulation: SCFAs promote regulatory T-cell (Treg) differentiation and IL-10 production, while inhibiting pro-inflammatory cytokines [23]. Butyrate particularly enhances IL-22 production by CD4+ T cells and innate lymphoid cells, strengthening mucosal immunity [23].

- Anti-inflammatory Effects: SCFAs reduce NF-κB activation and promote Nrf2 nuclear translocation, mitigating oxidative stress and inflammation [23].

- Metabolic Benefits: SCFAs protect against diet-induced obesity and improve insulin sensitivity. Propionate represses triglyceride accumulation via PPARα-responsive genes [23].

- Neuroprotective Activity: Cross-sectional studies show depressed individuals have lower levels of acetate and propionate [23]. SCFAs modulate microglial activation and blood-brain barrier integrity [22] [21].

- Cardiovascular Protection: Butyrate deficiency impairs baroreceptor sensitivity and blood pressure regulation [21]. SCFAs also counteract the atherosclerosis-promoting effects of TMAO [21].

Experimental Approaches for SCFA Research

Table 2: Standard Experimental Models for SCFA Research

| Methodology | Application | Key Parameters Measured | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| In vitro fermentation models (e.g., SIMGI) | Simulating colonic SCFA production | SCFA concentration (GC-MS/LC-MS), bacterial abundance | Controlled pH, sequential vessels mimicking different gut regions [24] |

| In vivo models (germ-free, gnotobiotic mice) | Mechanistic studies of SCFA functions | Tissue SCFA levels, receptor expression, inflammatory markers, metabolic phenotypes | 150-200 mM SCFA supplementation in drinking water; 1-6 mmol/kg intraperitoneal injection [23] |

| Cell culture systems (e.g., 3T3-L1, THP-1, primary colonoids) | Molecular pathway analysis | Gene expression (qPCR/RNA-seq), protein quantification (Western blot), histone acetylation status | SCFA concentrations typically 0.1-10 mM; HDAC inhibition assays [23] |

Figure 1: SCFA Signaling Pathways and Physiological Effects

Bile Acids: Microbial Transformers of Key Signaling Molecules

The Bidirectional Relationship Between Bile Acids and Gut Microbiota

Bile acids represent a paradigm of host-microbiome co-metabolism. The liver synthesizes primary bile acids (cholic acid [CA] and chenodeoxycholic acid [CDCA]), which are conjugated to glycine or taurine before biliary secretion [25]. Upon entry into the intestinal lumen, gut microbiota extensively modify these bile acids through two principal enzymatic activities: bile salt hydrolase (BSH) and bile acid 7α-dehydroxylation [25]. BSH enzymes, widely distributed across gut bacteria, deconjugate bile acids, while the 7α-dehydroxylation pathway, restricted to specific Clostridium species (clusters XVIa and XI), converts primary bile acids into secondary bile acids including deoxycholic acid (DCA) and lithocholic acid (LCA) [25] [26]. The size and composition of the bile acid pool are thus regulated through a dynamic interplay between host synthesis and microbial metabolism.

Bile Acids as Regulatory Molecules and Disease Mediators

Bile acids function beyond their classical roles in lipid digestion, acting as important signaling molecules through activation of specific receptors, particularly the farnesoid X receptor (FXR) and G protein-coupled bile acid receptor 1 (TGR5) [25] [26]. The composition of the bile acid pool significantly influences gut microbial community structure, with more hydrophobic bile acids like DCA exhibiting potent antimicrobial effects [25]. Perturbations in bile acid metabolism have significant pathological consequences:

- Cirrhosis: Progression of cirrhosis is associated with decreased bile acid delivery to the intestine, resulting in dysbiosis characterized by reduced populations of bile acid-transforming bacteria (Blautia, Ruminococcaceae) and expansion of potential pathogens (Enterobacteriaceae) [25].

- Liver Cancer: Secondary bile acids, particularly DCA, promote hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) through induction of senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) in hepatic stellate cells [25].

- Metabolic Disease: Bile acid signaling through FXR and TGR5 regulates glucose, lipid, and energy metabolism, making these pathways attractive therapeutic targets [26].

Methodologies for Bile Acid Research

Table 3: Experimental Approaches for Bile Acid-Microbiome Studies

| Technique | Application | Key Readouts |

|---|---|---|

| In vitro biotransformation assays | Screening bacterial BA metabolism | BA profile changes (LC-MS/MS), enzyme activity (BSH, 7α-dehydroxylase) |

| Gnotobiotic mouse models | Establishing causal relationships | BA pool size/composition, host gene expression, metabolic phenotypes |

| Targeted bile acidomics | Quantitative BA profiling | >50 individual BA species in feces, serum, liver tissue |

| FXR/TGR5 reporter assays | BA signaling potential | Receptor activation, downstream gene targets (e.g., FGF19, GLPs) |

Figure 2: Bile Acid Metabolism and Host Interactions

Vitamins: Microbial Synthesis and Modification

Gut Microbiota as a Source of Essential Vitamins

The gut microbiota contributes significantly to the host's vitamin status, particularly for fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) and certain water-soluble vitamins (B group, K) [27]. This relationship is bidirectional: the microbiota synthesizes vitamins and transforms dietary vitamins, while vitamins simultaneously shape the microbial community structure and function. For instance, specific gut bacteria produce vitamin K and multiple B vitamins, while vitamin D receptor (VDR) signaling influences microbial composition [27]. The metabolic interplay between vitamins and gut microbiota affects host physiology through multiple mechanisms, including immune modulation, maintenance of epithelial barrier integrity, and regulation of metabolic homeostasis.

Implications for Host Physiology and Disease

Vitamin-microbiota interactions have profound implications for human health:

- Immune Function: Vitamin A metabolites (retinoic acid) and vitamin D directly modulate immune cell differentiation and function, influencing susceptibility to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and other immune-mediated conditions [27].

- Barrier Integrity: Vitamins A, D, and E contribute to maintaining intestinal epithelial barrier function, preventing translocation of bacterial products and subsequent systemic inflammation [27].

- Neurological Health: Gut microbiota-derived B vitamins influence neurological function through their roles as cofactors in neurotransmitter synthesis and myelin formation [27].

Methodological Toolkit for Metabolite Research

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Microbial Metabolite Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Inhibitors | GPR41/43 antagonists, FXR antagonists (guggulsterone), TGR5 antagonists | Pathway blockade to establish mechanistic causality |

| Recombinant Enzymes | Purified BSH, 7α-dehydroxylase complexes | In vitro characterization of microbial BA transformations |

| Synthetic Metabolites | Stable isotope-labeled SCFAs (13C-acetate), deuterated bile acids | Metabolic fate tracing, quantitative MS standards |

| Receptor Reporter Systems | FXR-Luc, TGR5-Luc reporter cell lines | High-throughput screening of metabolite receptor activation |

| Specialized Growth Media | Vitamin-free, fiber-defined, BA-defined media | Controlled manipulation of microbial metabolic output |

| Chlorotoluron-d6 | Chlorotoluron-d6, CAS:1219803-48-1, MF:C10H13ClN2O, MW:218.71 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Vitamin D2-d6 | Vitamin D2-d6 Stable Isotope | Vitamin D2-d6 (Ergocalciferol-d6) is a deuterated tracer for metabolic, pharmacokinetic, and nutritional research. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

Advanced Computational and Experimental Models

The field is rapidly advancing with innovative tools that enable more predictive modeling of metabolite-host interactions:

- coralME: A recently developed computational tool that rapidly generates genome-scale models of microbial metabolism from multi-omics data, predicting how microbes respond to nutrients and produce metabolites in health and disease [19].

- ME-models: These metabolism and expression models link microbial genomes to phenotypic outcomes, providing unprecedented resolution into microbial community behavior [19].

- Humanized mouse models: Germ-free mice transplanted with human microbiota provide physiologically relevant systems for studying metabolite-host interactions in vivo [24].

- Complex in vitro systems: Advanced gut simulators (e.g., SIMGI, TIM) replicate colonic conditions for studying metabolite production and absorption under controlled conditions [24].

Implications for Drug Discovery and Development

The growing understanding of microbial metabolites has profound implications for pharmaceutical development. First, the microbiome represents a significant source of interindividual variability in drug response, as microbial enzymes can directly metabolize drugs or modulate host metabolism [24]. For instance, microbial β-glucuronidases reactivate the chemotherapeutic irinotecan to its toxic form, causing dose-limiting diarrhea [24]. Second, microbial metabolites and their receptors represent promising novel therapeutic targets. Approaches include:

- Developing FXR and TGR5 agonists/antagonists to modulate metabolic diseases [26].

- Using SCFA receptor agonists to treat inflammatory and neurological conditions [23] [22].

- Engineering BSH inhibitors to manipulate bile acid pool composition for metabolic benefits [25] [26].

- Implementing dietary interventions that selectively modulate microbial metabolite production as adjuvant therapies [19] [21].

The pharmaceutical industry is increasingly integrating microbiome considerations into drug discovery pipelines, employing in silico databases like the Interactome of Microbiome-Derived Metabolites and Drugs (IMMD) to predict drug-microbiome interactions early in development [24]. Standardized tools and reference materials are needed to fully capture these complex interactions and improve the safety and efficacy of new chemical entities.

SCFAs, bile acids, and vitamins represent three fundamental classes of microbial metabolites that mediate host-microbiome communication with far-reaching effects on health and disease. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the production, transformation, and signaling mechanisms of these metabolites provides critical insights into pathophysiology and therapeutic opportunities. The continuing development of sophisticated experimental models, computational tools, and analytical technologies will further decipher the complex metabolic interplay between host and microbiota. Integration of this knowledge into drug discovery pipelines holds promise for developing novel therapeutics that target microbial metabolic pathways or harness beneficial metabolites for disease treatment. As our understanding of these functional cores deepens, we move closer to precision interventions that modulate specific microbial functions to restore and maintain human health.

Dysbiosis is defined as a disturbance in the homeostasis of the commensal microbial community, characterized by an imbalance in the composition and function of the microorganisms residing in a particular environment [28] [29]. This imbalance represents a critical transition from a beneficial symbiotic relationship between host and microbiota to a state associated with disease pathogenesis. In the symbiotic state, known as eubiosis, the microbial community maintains a balanced composition that supports numerous host physiological functions, including nutrient metabolism, barrier integrity, and immune regulation [30]. The disruption of this delicate equilibrium manifests through several recognizable patterns: loss of beneficial microorganisms, overgrowth of potentially harmful organisms, and reduction in overall microbial diversity [28] [31] [29]. While these types often coexist, they provide a framework for understanding how dysbiosis contributes to disease processes across multiple body sites, particularly in the gastrointestinal tract.

The human gut represents the most extensively studied microbiome, housing approximately 10¹ⴠbacterial cells encompassing over 1000 different bacterial species, with Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes constituting the dominant phyla in healthy individuals [28] [2]. This complex ecosystem engages in constant cross-talk with the host, creating a homeostatic balance that maintains gastrointestinal health and provides colonization resistance against pathogens [28] [2]. When this balance is disrupted, the protective functions of the microbiota are compromised, potentially leading to or exacerbating a wide range of diseases. Research has established associations between dysbiosis and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), obesity, allergic disorders, type 1 diabetes mellitus, autism, and colorectal cancer in both human and animal models [28]. The transition from symbiosis to dysbiosis can be triggered by multiple factors, including host genetics, antibiotic use, dietary changes, infections, and environmental exposures [32] [29] [30].

Table 1: Types of Dysbiosis and Their Characteristics

| Type of Dysbiosis | Key Characteristics | Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| Loss of Beneficial Organisms | Decrease in commensal bacteria diversity; Reduction in Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Bifidobacterium spp., and Bacteroides [28] [29] | Reduced production of anti-inflammatory metabolites like butyrate; Impaired T-regulatory cell induction; Weakened gut barrier function [28] [29] |

| Expansion of Pathobionts | Increase in Enterobacteriaceae family (e.g., AIEC), Ruminococcus gnavus; Rise in sulphate-reducing bacteria [28] | Increased production of toxic metabolites (e.g., hydrogen sulfide); Triggering of pro-inflammatory responses; Epithelial barrier damage [28] |

| Loss of Microbial Diversity | Reduced overall species richness; Loss of obligate anaerobes with expansion of facultative anaerobes [28] [29] | Ecosystem instability; Reduced metabolic capacity; Diminished colonization resistance [28] [2] |

Quantifying Dysbiosis: Microbial Signatures in Disease

The identification of specific microbial signatures associated with disease states has been instrumental in understanding dysbiosis. Advanced sequencing technologies have enabled researchers to move beyond associations toward defining quantitative dysbiosis indices that can potentially serve as diagnostic tools or therapeutic targets.

In inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), dysbiosis demonstrates a characteristic pattern marked by a pronounced decrease in commensal bacteria diversity, particularly affecting the Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes phyla [28]. More specifically, the dysbiosis signature in Crohn's disease is characterized by five key bacterial species: an increase in Ruminococcus gnavus, accompanied by decreases in Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Bifidobacterium adolescentis, Dialister invisus, and an unknown species from Clostridium cluster XIVa [28]. This signature exemplifies the multifaceted nature of dysbiosis, encompassing both the loss of beneficial taxa and the expansion of potentially detrimental ones. The functional implications are significant, as F. prausnitzii represents a major butyrate-producing bacteria in the intestines, and its reduction compromises energy supply to colonocytes and weakens the epithelial barrier [28].

The composition of a "healthy" microbiota varies substantially between individuals and is influenced by factors including age, genetics, and early life exposures [30] [2]. However, core principles of a healthy gut microbiota include high taxonomic diversity, stable core microbiota, and functional redundancy that ensures ecosystem resilience [2]. Quantitative assessments reveal that dysbiosis often involves measurable shifts in the relative abundances of key bacterial groups, which can be tracked through dysbiosis indices. Interestingly, research has shown that unaffected relatives of patients with Crohn's disease also exhibit altered intestinal microbiota compared to healthy controls, suggesting dysbiosis may precede clinical disease manifestation in genetically susceptible individuals [28].

Table 2: Quantitative Microbial Changes in Dysbiosis-Associated Conditions

| Condition | Increased Taxa | Decreased Taxa | Functional Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory Bowel Disease | Ruminococcus gnavus, Enterobacteriaceae, Sulphate-Reducing Bacteria [28] | Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Bifidobacterium adolescentis, Dialister invisus, Clostridium cluster XIVa, Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes [28] | Reduced butyrate production; Increased hydrogen sulfide; Bile acid dysmetabolism [28] |

| Obesity (Model Systems) | Firmicutes (in some studies) [28] | Bacteroidetes (in some studies) [28] | Increased energy harvest; Altered SCFA profiles; Fecal transplant transmissibility [28] [32] |

| Antibiotic-Induced Dysbiosis | Enterobacteriaceae, Lactobacillaceae, Verrucomicrobiaceae [29] | Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Clostridiales clusters [29] | Reduced microbial diversity; Loss of colonization resistance [29] [2] |

Mechanisms of Dysbiosis in Disease Pathogenesis

Immune Dysregulation and Barrier Disruption

The mechanistic links between dysbiosis and disease pathogenesis involve complex interactions between microbial communities and host systems. One well-established pathway involves the disruption of intestinal barrier function coupled with dysregulated immune responses. In a healthy state, commensal bacteria such as Bacteroides fragilis and certain Clostridium strains induce regulatory T cells (Tregs) through specific mechanisms—PSA polysaccharide signaling through TLR2 in the case of B. fragilis, and TGF-β induction by Clostridium strains—which maintains immune tolerance and protects against inflammation [29]. During dysbiosis, the loss of these beneficial organisms diminishes Treg induction, creating an environment permissive to inflammation.

Concurrently, dysbiosis characterized by a decrease in butyrate-producing bacteria (e.g., F. prausnitzii) and an increase in sulphate-reducing bacteria leads to a compromised epithelial barrier [28]. Butyrate serves as a crucial energy source for colonocytes and supports the expression of tight junction proteins, while hydrogen sulfide produced by sulphate-reducing bacteria can inhibit butyrate utilization and directly damage the epithelium [28]. This combination of reduced butyrate and increased hydrogen sulfide diminishes barrier integrity, allowing bacterial translocation into the lamina propria. In genetically susceptible individuals with impaired bacterial clearance mechanisms, this translocation triggers excessive Toll-like receptor stimulation, pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion, and activation of adaptive immune responses, culminating in chronic inflammation [28].

Metabolic Consequences of Dysbiosis

Dysbiosis significantly alters the metabolic landscape of the gut environment, with systemic implications. The bile acid metabolism pathway represents a crucial mechanism linking microbial imbalance to disease. Under healthy conditions, Firmicutes and Bacteroides—the major bacterial groups decreased in IBD-associated dysbiosis—perform deconjugation of bile acids through bile salt hydrolase activity [28]. During dysbiosis, reduced capacity for bile acid transformation disrupts the anti-inflammatory signaling normally mediated by bile acids, potentially exacerbating intestinal inflammation [28]. This defective bile acid metabolism is particularly evident during IBD flares, suggesting it may serve both as a marker and mediator of disease activity.

Another emerging mechanism involves oxygenation of the gut environment. The healthy intestine maintains a low oxygen level that supports obligate anaerobes. Dysbiosis frequently features a decrease in Firmicutes (obligate anaerobes) and an increase in facultative anaerobes like Enterobacteriaceae, suggesting a fundamental disruption of the anaerobic gut environment [28]. This shift may be driven by increased reactive oxygen species during inflammation, creating a selective advantage for oxygen-tolerant bacteria and further perpetuating dysbiosis [28]. The resulting alteration in microbial metabolism affects the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which normally influence everything from normal muscle function to inflammatory responses [32].

Diagram 1: The transition from symbiotic health to dysbiosis-associated disease involves multiple interconnected pathways. Environmental triggers, host genetics, antibiotics, and diet can disrupt the balanced microbiota, leading to functional impairments that drive disease pathogenesis.

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Animal Models for Dysbiosis Research

The investigation of dysbiosis mechanisms relies heavily on animal models, particularly germ-free (GF) mice, which provide a controlled system for studying host-microbe interactions. These models have been instrumental in establishing causality rather than mere association between microbial communities and disease phenotypes. For instance, studies have demonstrated that germ-free mice receiving fecal microbiota transplants from obese donors gain significantly more weight than those receiving transplants from lean donors, directly implicating the microbiota in metabolic disease [32]. Similarly, research using GF mice colonized with specific bacterial consortia has identified particular organisms, such as Bacteroides fragilis and certain Clostridium strains, that induce regulatory T cells and protect against inflammatory conditions [29].

The translation of findings from rodent models to humans requires careful consideration of interspecies differences in microbiota composition and host physiology. While human and murine gut microbiota share approximately 90% overlap at the phyla and genera levels, significant differences exist in the relative abundances of specific taxa [2]. The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio is notably higher in humans than in mice, and each species harbors unique genera—humans carry Faecalibacterium and Megasphera, while mice harbor Mucispirillum [2]. Additionally, differences in immune system regulation and transcription factor binding sites between species necessitate validation of rodent findings in human contexts [2]. Despite these limitations, rodent models remain invaluable for probing mechanistic pathways and testing therapeutic interventions in a controlled manner.

Table 3: Experimental Models in Dysbiosis Research

| Model System | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Germ-Free (GF) Mice | Establishing causality; Studying microbial colonization; Host immune development [29] [2] | No resident microbiota; Controlled microbial exposure; Direct manipulation of variables [2] | Artificial environment; Immature immune system; Limited translational relevance [2] |

| Humanized Mice (GF mice + human microbiota) | Studying human-specific microbes; Personalized microbiota responses [2] | Human-relevant microbial communities; Maintains experimental control [2] | Still artificial environment; Mouse physiology differs from human [2] |

| Canine Models | Natural disease studies; Translational research for IBD, obesity [32] | Shared environment with humans; Spontaneous diseases; Similar gut microbiome to humans [32] | Genetic heterogeneity; Limited reagents; Ethical considerations [32] |

| Porcine Models | Nutrition studies; Microbiome development [32] | Similar GI tract and diet to humans; Comparable phenotype [32] | Cost; Housing requirements; Limited genetic tools [32] |

Methodologies for Dysbiosis Characterization

The comprehensive characterization of dysbiosis requires multi-omics approaches that capture taxonomic composition, functional potential, and metabolic activity. High-throughput 16S rRNA gene sequencing enables taxonomic profiling of bacterial communities, while shotgun metagenomics provides a broader view of the entire genetic repertoire, including bacteria, viruses, fungi, and archaea [28] [2]. Metatranscriptomics, metaproteomics, and metabolomics further illuminate the functional state of the microbial community by measuring gene expression, protein production, and metabolic output, respectively [6] [2].

Standardized protocols for sample collection, DNA extraction, and bioinformatic analysis are critical for generating comparable data across studies. For intestinal dysbiosis assessment, fecal samples represent the most accessible material, but mucosal biopsies may provide more relevant information for diseases like IBD where mucosa-associated microbes directly interact with host tissues [32]. Comprehensive digestive stool analysis examines the types and amounts of bacteria and yeast present, though these studies can be complex to perform and interpret [32]. Emerging techniques include the use of gas-sensing capsules to measure intraluminal gas production [6] and analysis of bacterial DNA in blood as a potential biomarker for systemic microbial translocation [6]. The field is also developing standardized dysbiosis indices, such as the GA-map Dysbiosis Test, to quantify the degree of microbial imbalance in clinical and research settings [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Dysbiosis Investigation

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Germ-Free (GF) Rodent Systems | Provides microbiota-free baseline for colonization studies; Enables determination of causal relationships [29] [2] | Studying immune development; Microbial colonization resistance; Fecal microbiota transplantation [29] [2] |

| Gnotobiotic Animals | Animals with defined, known microbial consortia; Enables reductionist approaches to community function [29] | Identifying minimal functional communities; Probing microbe-microbe interactions; Determining keystone species [29] |

| 16S rRNA Sequencing Reagents | Amplification and sequencing of bacterial 16S rRNA gene; Taxonomic profiling of microbial communities [28] [2] | Comparative community analysis; Dysbiosis indices; Tracking microbial changes over time [28] [6] |

| Shotgun Metagenomics Kits | Comprehensive DNA sequencing of all microbial genomes in a sample; Functional gene cataloging [2] | Discovering novel organisms; Identifying metabolic pathways; Strain-level analysis [2] |

| Metabolomics Platforms | Measurement of microbial metabolites (SCFAs, bile acids, neurotransmitters) [6] | Connecting microbial function to host physiology; Identifying bioactive molecules; Biomarker discovery [28] [6] |

| Cell Culture Systems (e.g., organoids, transwell models) | Modeling host-microbe interactions in vitro; Studying barrier function and immune responses [29] | Mechanistic studies of specific host-microbe interactions; High-throughput screening of microbial products [29] |

| Riociguat | Riociguat|Soluble Guanylate Cyclase (sGC) Stimulator | Riociguat is a first-in-class sGC stimulator for pulmonary hypertension research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human consumption. |

| Bisphenol A-13C2 | Bisphenol A-13C2, CAS:263261-64-9, MF:C15H16O2, MW:230.27 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Diagram 2: Integrated experimental workflow for dysbiosis research, spanning sample collection, multi-omics characterization, bioinformatic analysis, and mechanistic validation in model systems.

Dysbiosis represents a critical transition from a mutually beneficial host-microbe relationship to a pathological state characterized by microbial imbalance and functional disruption. The comprehensive definition of dysbiosis encompasses three interrelated phenomena: loss of beneficial microorganisms, expansion of potentially harmful organisms, and reduction in overall microbial diversity [28] [29]. These changes disrupt essential microbial functions, including immune education, barrier maintenance, and metabolic regulation, creating pathways to disease [28] [29]. The mechanistic understanding of how dysbiosis contributes to conditions like IBD, obesity, and metabolic disorders has advanced significantly through integrated approaches combining multi-omics technologies, gnotobiotic animal models, and sophisticated bioinformatic analyses [28] [6] [29].

Future research directions will focus on moving beyond associations to establish causal mechanisms, with particular emphasis on microbiome metrics for clinical application [6], personalized microbiome-based interventions [6], and therapeutic strategies such as next-generation probiotics, prebiotics, and targeted microbial consortia [6] [30]. The ongoing development of standardized dysbiosis indices and validated protocols will enhance reproducibility and clinical translation. As our understanding of the transition from symbiosis to dysbiosis deepens, so too will opportunities to develop novel diagnostics and therapeutics that target the microbiome to restore health and prevent disease.

From Correlation to Causation: Advanced Methodologies for Functional Microbiome Research

The human gut microbiome plays a crucial role in both health and disease, influencing conditions ranging from metabolic disorders to inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer. The choice of sequencing technology—16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene sequencing or whole-genome shotgun metagenomics—profoundly impacts the resolution, depth, and biological insights attainable from microbial community analysis. This technical review provides a comprehensive comparison of these foundational methodologies, examining their theoretical principles, practical performance in disease association studies, and methodological considerations for implementation. Within the context of gut microbiome-health research, we demonstrate that while 16S rRNA sequencing offers a cost-effective entry point for taxonomic profiling, shotgun metagenomics provides superior taxonomic resolution and direct functional insights, albeit with higher computational and financial costs. Evidence from multiple clinical studies reveals that both techniques can effectively distinguish disease-associated dysbiosis, though shotgun sequencing often captures a more comprehensive picture of microbial community structure and function.

The human gut microbiome constitutes a complex ecosystem of bacteria, archaea, viruses, and eukaryotes that collectively contribute to host physiology through metabolic functions, immune modulation, and barrier protection [33]. Dysbiosis, or an alteration in this microbial community, has been associated with numerous disease states including inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), colorectal cancer, and autoimmune disorders [34] [35]. Understanding the precise nature of these microbial alterations requires sophisticated analytical approaches that can characterize community composition and function.

The evolution of culture-independent techniques revolutionized microbiome research, with next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies now enabling comprehensive profiling of microbial communities [33]. Two principal NGS approaches have emerged: 16S rRNA gene sequencing and shotgun metagenomic sequencing. The 16S method targets the conserved 16S ribosomal RNA gene as a phylogenetic marker, while shotgun sequencing randomly fragments and sequences all DNA present in a sample [36] [37]. The choice between these methods carries significant implications for project design, analytical capabilities, and biological interpretation, particularly in the context of gut microbiome-disease association studies where resolution, cost, and functional insights must be carefully balanced.

Technical Foundations of 16S and Shotgun Sequencing

16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

The 16S rRNA gene is a highly conserved bacterial marker containing nine variable regions (V1-V9) that provide taxonomic discrimination between organisms [35]. This method employs polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to amplify specific hypervariable regions (typically V3-V4 or V4) using universal primers, followed by sequencing of the resulting amplicons [38] [37].

Key technical considerations:

- Region selection: Different variable regions offer varying degrees of taxonomic resolution; no single region perfectly discriminates all species [38]

- PCR biases: Primer specificity and amplification efficiency can skew abundance measurements [38]

- Gene copy number variation: Bacteria contain varying copies of the 16S rRNA gene (e.g., 1-15 copies), potentially distorting abundance estimates [38]

- Database dependence: Taxonomic classification relies on reference databases (SILVA, Greengenes, RDP) that differ in size, curation, and update frequency [38]

Recent advancements include full-length 16S sequencing using long-read technologies (e.g., PacBio), which provides enhanced taxonomic resolution compared to short-read approaches targeting specific variable regions [35].

Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing

Shotgun metagenomics applies random fragmentation to all DNA in a sample, followed by high-throughput sequencing without target-specific amplification [37]. This approach enables:

- Strain-level discrimination of microorganisms

- Identification of viruses, fungi, and archaea alongside bacteria

- Direct assessment of functional potential through gene content analysis [38] [39]

Technical challenges include:

- Host DNA contamination: Particularly problematic in tissue samples, requiring depletion strategies or increased sequencing depth [37]

- Computational complexity: Substantial hardware and bioinformatics resources needed for analysis [38]

- Reference database limitations: Unknown or uncharacterized taxa may remain unidentified despite sequencing [38]

Table 1: Core Technical Specifications of 16S rRNA and Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing

| Parameter | 16S rRNA Sequencing | Shotgun Metagenomics |

|---|---|---|

| Target Region | 16S rRNA gene (specific variable regions) | Entire genome (all DNA) |

| PCR Amplification | Required (primers target 16S) | Not required (random fragmentation) |

| Taxonomic Resolution | Genus level (species level with full-length) | Species and strain level |

| Multi-Kingdom Coverage | Bacteria and Archaea only | Bacteria, Archaea, Viruses, Fungi, Protists |

| Functional Profiling | Indirect inference from taxonomy | Direct assessment of genes and pathways |

| Host DNA Interference | Minimal (PCR enriches microbial target) | Significant (may require depletion) |

| Reference Databases | SILVA, Greengenes, RDP | NCBI RefSeq, GTDB, UHGG |

Performance Comparison in Disease Association Studies

Taxonomic Resolution and Diversity Assessments

Multiple studies have directly compared the performance of 16S and shotgun sequencing in clinical contexts. A 2024 study comparing both techniques in colorectal cancer (CRC), advanced colorectal lesions, and healthy gut microbiota found that 16S detects only part of the gut microbiota community revealed by shotgun, with 16S abundance data being sparser and exhibiting lower alpha diversity [38]. At lower taxonomic ranks (species level), the two methods showed substantial disagreement, partially attributable to differences in reference databases [38].

In pediatric ulcerative colitis research, both 16S and shotgun sequencing consistently identified reduced alpha diversity in patients compared to healthy controls, though shotgun data provided superior species-level resolution of the dysbiotic taxa [40]. Notably, both methods achieved similar predictive accuracy for disease status (AUROC ≈ 0.90), suggesting that for case-control discrimination, 16S may provide sufficient resolution [40].