Validating Microbiome Analysis: From Consensus Standards to Clinical Translation

This article synthesizes current international consensus and best practices for validating microbiome analysis approaches, targeting researchers and drug development professionals.

Validating Microbiome Analysis: From Consensus Standards to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article synthesizes current international consensus and best practices for validating microbiome analysis approaches, targeting researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of microbiome science, evaluates methodological pipelines from 16S rRNA to multi-omics technologies, addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization challenges in standardization, and establishes validation frameworks for comparative analysis. By integrating the latest evidence from clinical practice, drug development pipelines, and analytical benchmarking studies, this resource provides a comprehensive roadmap for implementing robust, reproducible microbiome analysis that bridges the gap between research findings and clinical application.

Establishing the Groundwork: Core Concepts and Evolving Definitions in Microbiome Science

In microbiome research, the terms "microbiome" and "microbiota" are frequently used interchangeably, creating confusion within the scientific community and in literature. However, these terms represent distinct concepts with important differences in scope and meaning. A precise understanding of this terminology is fundamental for rigorous scientific communication, especially in the context of validating consensus approaches for microbiome analysis. This guide provides a detailed comparison of these core concepts, tracing their historical development and contextualizing them within contemporary analytical frameworks. Establishing this conceptual clarity is essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working to standardize methodologies and interpret data across studies.

Core Definitions and Conceptual Distinctions

Defining Microbiota and Microbiome

The fundamental distinction lies in the scope of each term. Microbiota refers specifically to the community of living microorganisms themselves—the bacteria, archaea, fungi, algae, and small protists—inhabiting a defined environment [1] [2] [3]. In contrast, the microbiome encompasses a broader ecological landscape, including not only the microorganisms but also their "theatre of activity" [4] [5] [3]. This comprises their structural elements (e.g., microbial and host), metabolites, mobile genetic elements, and the surrounding environmental conditions [1] [2]. In essence, the microbiota constitutes the living inhabitants, while the microbiome represents the entire habitat, including the inhabitants, their functions, and their interactions.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Microbiota and Microbiome

| Feature | Microbiota | Microbiome |

|---|---|---|

| Core Definition | The community of living microorganisms in a defined environment [1] [2] | The entire habitat, including microorganisms, their activities, and the environmental conditions [4] [3] |

| Composition | Bacteria, Archaea, Fungi, Protists [1] [3] | Microbiota, their genomes, metabolites, and the surrounding environment [1] [2] |

| Genetic Focus | Not applicable to the term itself | Includes the collective genetic material (metagenome) of the community [1] [6] |

| Key Scope | Taxonomic composition and abundance of organisms [2] | Structural and functional ecology of the microbial niche [4] [5] |

The "Theatre of Activity": Understanding the Microbiome's Breadth

The phrase "theatre of activity," originating from the influential 1988 definition by Whipps et al., is crucial for understanding the microbiome's comprehensive nature [4] [5] [3]. It signifies that the microbiome includes:

- The Microorganisms: The entire cast of microbial players (the microbiota).

- Their Genomic Blueprints: The collective genetic information (the metagenome) that dictates functional potential [1].

- Their Metabolic Outputs: The molecules produced and consumed, such as nutrients, signaling molecules, and waste products.

- The Environmental Stage: The surrounding physicochemical conditions that shape and are shaped by the microbial community.

This holistic view positions the microbiome as a dynamic, interactive system rather than merely a list of inhabitants.

Visualizing the Conceptual Relationship

The following diagram illustrates the hierarchical relationship between the key concepts of microbiota, metagenome, and microbiome, showing how they collectively form a functional ecological unit.

Historical Evolution of the Concepts

Key Milestones in Microbiome Research

The field of microbiome research did not emerge in a vacuum; it evolved from centuries of microbiological discovery, driven by technological innovation and paradigm shifts in understanding microbes' roles in health and disease. The following timeline captures the pivotal moments in this scientific journey.

Table 2: Historical Timeline of Key Concepts and Discoveries

| Year(s) | Key Figure(s) | Conceptual or Technological Advancement | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1670s | Antonie van Leeuwenhoek [3] | Discovery of microorganisms using first microscopes [4] [3] | Revealed the previously invisible world of microbes |

| 1880s | Robert Koch [3] | Koch's postulates linking microbes to disease [4] [3] | Established medical microbiology; focus on pathogens |

| 1888-1920s | Sergei Winogradsky [5] [3] | Founded microbial ecology; studied nitrification and chemosynthesis [4] [5] | Paradigm shift to beneficial environmental microbes and communities |

| 1988 | Whipps et al. [5] | First formal definition of the "microbiome" [4] [5] [3] | Introduced holistic concept of microbes plus their "theatre of activity" |

| 1977 | Carl Woese & George Fox [4] [3] | 16S rRNA gene as a phylogenetic marker [4] [3] | Enabled cultivation-independent community analysis |

| 2001 | Lederberg & McCray [1] | Popularized the term "microbiome" in genomics context [1] | Brought term to wider scientific audience |

| 2008-Present | NIH & International Consortium [1] [4] | Human Microbiome Project and related large-scale initiatives [1] [4] | High-throughput sequencing revealed microbiome's critical role in host health |

The Origin of "Microbiome" and a Paradigm Shift

A common misconception is that Nobel laureate Joshua Lederberg coined the term "microbiome" in 2001. While he and McCray played a key role in popularizing it within genomics, the term first appeared in a 1988 paper by Whipps and colleagues [5]. Critically, the word is a portmanteau of "microbe" and "biome," emphasizing an ecological system, and is not a direct derivative of the '-omics' family of terminology [5]. This origin underscores that the term was conceived from an ecological perspective to describe a microbial habitat, not merely a genomic catalogue.

The intellectual foundation for microbiome research traces back to the pioneering work of Sergei Winogradsky in the late 19th century. His development of the Winogradsky Column and his studies on nitrifying bacteria demonstrated that microbes function as interconnected communities in their natural environments, with the metabolic products of some species creating niches for others [5]. This stood in stark contrast to the pure-culture techniques of medical microbiology and established the core principle of microbial ecology: to understand microbes, one must study them in context [5]. This represents a fundamental paradigm shift from viewing microbes as isolated pathogens to understanding them as cooperative communities essential for ecosystem functioning.

Methodological Approaches and Research Toolkit

Standardized Analytical Workflows

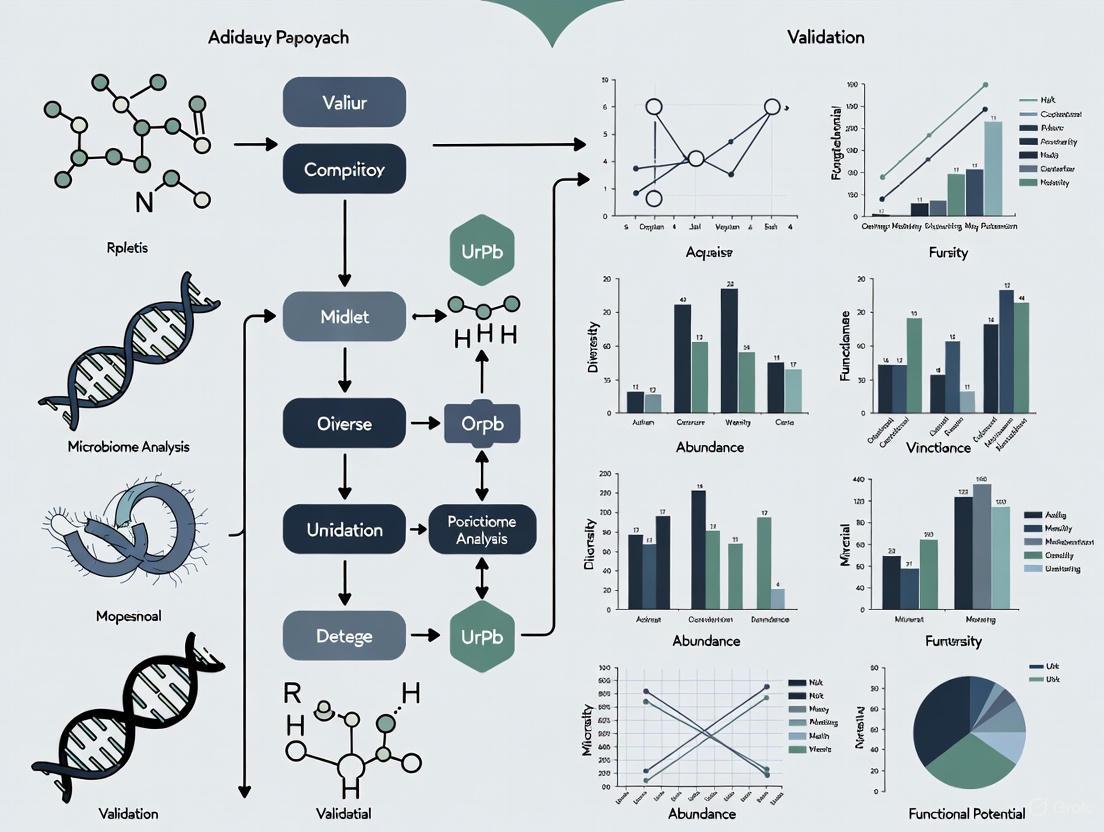

Modern microbiome analysis relies on a multi-layered, omics-driven approach to move beyond cataloging microbiota members (who is there) to understanding functional potential and activity (what they are doing). The international scientific community emphasizes the need for standardization across this workflow to ensure data comparability and reproducibility [4] [7]. The following diagram outlines the core steps in a comprehensive microbiome analysis protocol, from sample collection to functional interpretation.

Essential Research Reagents and Technologies

Executing the workflows above requires a suite of specialized reagents and technologies. The following table details key components of the researcher's toolkit for conducting robust microbiome studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Microbiome Analysis

| Reagent / Technology | Primary Function | Application in Microbiome Research |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Stabilization Buffers | Preserves nucleic acid integrity at point of collection [7] | Critical for accurate representation of microbial community; prevents shifts post-sampling |

| DNA Extraction Kits (for stool, soil, etc.) | Lyses diverse cell walls and purifies total community DNA [7] | Yield of pure, inhibitor-free DNA is a major confounder; must be standardized for comparison |

| 16S/ITS rRNA Primer Sets | Amplifies hypervariable regions for taxonomic identification [4] [3] | Workhorse for cost-effective community profiling; defines microbiota composition |

| Shotgun Metagenomic Library Prep Kits | Prepares entire genomic DNA for high-throughput sequencing [7] | Enables analysis of all genes (metagenome) and organisms, including viruses and archaea |

| PCR Enzymes & Master Mixes | Amplifies target DNA sequences for detection and sequencing [4] | Used in amplicon sequencing and qPCR for absolute quantification of taxa |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines | Processes raw sequence data into biological insights [7] | For sequence quality control, taxonomy assignment, and functional annotation |

Consensus and Validation in Clinical Translation

Current State of Microbiome Testing

A significant outcome of microbiome research is the potential for clinical diagnostics and therapeutics. However, a 2024 international consensus statement highlights that the transition from research to routine clinical practice remains challenging [7]. The consensus panel, comprising multidisciplinary experts, concluded that there is currently insufficient evidence to widely recommend the routine use of microbiome testing in clinical practice [7]. This cautious stance stems from several factors: the complexity of sequencing datasets, difficulty disentangling correlation from causation, and the absence of a standardized framework for test interpretation and validation [7].

The consensus strongly recommends that providers of microbiome testing must communicate a "reasonable, reliable, transparent, and scientific representation of the test," making clients and clinicians aware of its limited evidence base [7]. Key technical recommendations for validation include:

- Appropriate Methodologies: Community profiling should use either amplicon sequencing (e.g., 16S rRNA) or shotgun metagenomic sequencing. Techniques like multiplex PCR or bacterial culture alone are not considered sufficient for microbiome testing [7].

- Reporting Standards: Test reports should detail the patient's medical history and the full test protocol, including methods of collection, storage, DNA extraction, and bioinformatic analysis to ensure transparency and reproducibility [7].

- Focus on Function: Moving beyond relative abundance data to functional metrics (e.g., gut microbiome health indices) is essential for future clinical applicability [7] [8].

Public and Professional Awareness

The need for validation and education is reflected in public understanding. A 2025 international survey revealed that while 71% of the public has heard the term "microbiota," only 24% know what it means exactly. Furthermore, awareness of "dysbiosis" (microbial imbalance) is even lower, at 34% [9]. The survey identified healthcare professionals as the most trusted source of information (81%), underscoring their critical role in guiding the validated application of microbiome science [9].

Distinguishing between microbiota as the community of microorganisms and microbiome as the comprehensive habitat including their genomic and metabolic activity is fundamental for scientific precision. This conceptual clarity, rooted in the ecological principles of Winogradsky and formally defined by Whipps, is a prerequisite for rigorous research. As the field advances, the consensus within the scientific community is clear: validating analytical protocols and establishing standardized frameworks are the critical next steps. For researchers and drug development professionals, this means prioritizing functional insights over mere compositional catalogs and adhering to evolving best practices. This disciplined approach is essential for translating the profound potential of microbiome research into reliable diagnostics and therapeutics.

The field of human microbiome research has witnessed explosive growth, revealing compelling associations between gut microbial communities and a vast range of intestinal and extraintestinal disorders [7]. This has catalyzed intense interest in exploiting the gut microbiome as a diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic monitoring tool in clinical practice [10]. Consequently, a burgeoning direct-to-consumer (DTC) market for microbiome testing has emerged, often claiming to guide clinical management. However, this enthusiasm has vastly outstripped the established scientific evidence, creating a landscape fraught with unsubstantiated claims, non-standardized methodologies, and potential for misdirected healthcare resources [10] [7] [11].

Recognizing these challenges, a multinational, multidisciplinary panel of 69 experts from 18 countries was convened to establish a foundational framework for the responsible development and use of microbiome diagnostics [10] [12] [13]. Using a structured Delphi method to achieve consensus, this panel produced a set of authoritative guidelines aimed at standardizing best practices, defining minimum requirements, and paving the way for evidence-based application in clinical medicine [7] [12]. This guide distills the core principles and technical standards from this consensus, providing researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a critical benchmark for evaluating, developing, and implementing clinical microbiome testing.

Core Consensus Principles and Minimum Requirements

The international consensus establishes a comprehensive framework organized around five key domains, from general principles to future outlook. The following table summarizes the pivotal statements ratified by the expert panel.

Table 1: Key Consensus Statements on Microbiome Testing in Clinical Practice

| Working Group Focus | Core Consensus Statement | Agreement Rate |

|---|---|---|

| General Principles & Minimum Requirements | Providers must communicate the test's limited clinical evidence transparently to customers and clinicians. | >80% [7] |

| Procedural Steps Before Testing | Direct patient requests for testing without clinical recommendation are discouraged. | >80% [7] |

| Microbiome Analysis | Appropriate modalities for community profiling are amplicon sequencing and whole-genome sequencing. | >80% [7] |

| Characteristics of Reports | Patient medical history and detailed test protocol must be included in the report. | >80% [7] |

| Relevance in Clinical Practice | There is currently insufficient evidence to recommend routine microbiome testing in clinical practice. | >80% [7] |

Pre-Testing Protocols and Patient Preparation

A critical recommendation is that microbiome testing should be initiated by a licensed healthcare professional—such as a physician, pharmacist, or dietitian—based on a clear clinical rationale [14] [12]. Self-prescription by patients is strongly discouraged to prevent inappropriate testing and misinterpretation of results [7]. The consensus advises against patients making changes to their usual diet or suspending treatments before sample collection, as the test should reflect the steady-state microbiome under normal conditions [14].

The collection of comprehensive clinical metadata is considered indispensable for contextualizing microbiome data. Essential variables include [7] [14] [12]:

- Personal patient features: Age, gender, body mass index (BMI), and gut transit time.

- Health status: Current and past medical conditions.

- Medications: Detailed history of drug intake, particularly antibiotics.

- Dietary information: Recent dietary patterns.

For sample integrity, the consensus emphasizes the use of a stool collection kit with a DNA preservative, testing within a recommended time frame, and long-term storage of fecal samples at -80°C in the laboratory [14].

Analytical Methods: From Sampling to Sequencing

The consensus provides clear guidance on the methodologies deemed appropriate for gut microbiome community profiling.

Table 2: Recommended Analytical Methods for Microbiome Testing

| Method | Description | Consensus Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA Gene Amplicon Sequencing | Sequences hypervariable regions of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene for taxonomic profiling. | Recommended for community profiling [7] [14] |

| Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing (MGS) | Random sequencing of all DNA in a sample, allowing for taxonomic and functional gene analysis. | Recommended for community profiling [7] [14] |

| Quantitative PCR (qPCR) & Bacterial Culture | Targets specific, pre-defined pathogens or genes; culture isolates specific culturable organisms. | Not a proxy for microbiome testing; useful for narrow, hypothesis-driven identification [7] [14] |

The expert panel unequivocally states that while techniques like multiplex PCR and bacterial culture are valuable for identifying specific pathogens, they "cannot be considered microbiome testing nor can be used as a proxy for microbiome profiling" [7]. This distinction is crucial for researchers designing validation studies.

For DNA analysis, the entire process must be meticulously controlled. This includes using optimized DNA extraction protocols with bead-beating for thorough cell lysis [15], incorporating appropriate controls throughout the process, and employing validated bioinformatics pipelines for data analysis [7]. The use of negative controls and biological mock communities is essential to account for contamination and technical biases, especially in low-biomass samples [15].

Diagram 1: The end-to-end workflow for clinically relevant microbiome testing, as recommended by the international consensus. The process emphasizes the central role of healthcare professionals and the critical steps of metadata collection and standardized laboratory protocols.

Reporting Standards and Interpretation

The consensus provides explicit guidance on the elements that must be included and excluded from a clinically-oriented microbiome test report.

Essential Components of the Report

- Patient Medical History: The report must be contextualized with relevant clinical information [7].

- Test Protocol Transparency: Detailed methodology covering stool collection, storage, DNA extraction, sequencing, and post-sequencing analyses must be provided [7] [14].

- Ecological and Taxonomic Measures: Reports should include alpha and beta diversity measures and a complete taxonomic profile at the deepest possible resolution (ideally species-level) [14].

- Comparison to Matched Controls: Results should be benchmarked against a matched control group (e.g., healthy individuals with similar age, BMI, and geography) to aid interpretation [14] [12].

What to Exclude from Reports

- Dysbiosis Indices and Phylum-Level Ratios: The consensus strongly advises against reporting oversimplified metrics like the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio, as they "do not capture the variation in the gut microbiome within the same host and between hosts and there is insufficient evidence to establish a causal relationship" with health [14] [12].

- Post-Testing Therapeutic Advice: A pivotal recommendation is that the testing provider should not offer specific therapeutic advice based on the results. This responsibility falls solely to the referring healthcare provider who understands the patient's full clinical context [14] [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Robust microbiome science depends on carefully selected reagents and materials at every stage. The following table details key components of a validated workflow.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Microbiome Testing

| Item | Function/Description | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Stool Collection Kit with DNA Preservative | Stabilizes microbial DNA at room temperature for transport. | Critical for preserving nucleic acid integrity; allows for practical sample collection outside lab [16]. |

| Bead-Beating Lysis Tubes | Homogenization and mechanical breakage of tough microbial cell walls. | Essential for DNA extraction from Gram-positive bacteria and spores; prevents taxonomic bias [15]. |

| Validated DNA Extraction Kit | Isolates total genomic DNA from complex stool matrix. | Must be optimized for fecal material; performance varies significantly between kits [15]. |

| PCR Primers for 16S rRNA Gene | Amplifies target hypervariable regions for sequencing. | Choice of region (e.g., V4) impacts taxonomic resolution; must be well-validated [17] [15]. |

| Mock Microbial Communities | Defined mixtures of known microorganisms or their DNA. | Serves as a positive control to benchmark accuracy, precision, and bias in the entire workflow [15]. |

| Negative Control Reagents | Sterile water or buffer taken through the entire extraction and sequencing process. | Identifies contamination from reagents, kits, or the laboratory environment [15]. |

| Bioinformatic Pipelines & Databases | Software for processing raw sequences into taxonomic and functional profiles. | Must use curated, up-to-date databases (e.g., GTDB, SILVA); parameters significantly impact results [7] [15]. |

Current Clinical Relevance and Future Directions

The consensus is unequivocal about the current state of the field: "there is insufficient evidence to widely recommend the routine use of microbiome testing in clinical practice" [7] [14]. The foundational role of this consensus is to provide a framework for the dedicated studies needed to build this evidence.

Future progress hinges on a concerted shift from descriptive, association-based research to mechanistic studies that elucidate cause-and-effect relationships [14]. This will require:

- Standardization and Quality Control: Widespread adoption of the minimum requirements and best practices outlined in the consensus.

- Advanced Study Designs: Implementation of large, longitudinal cohorts with deep phenotyping to control for confounders that obscure causal links with human diseases [7] [14].

- Functional Insights: Leveraging multi-omics approaches (metatranscriptomics, metabolomics, proteomics) to move beyond taxonomy and understand microbial function in situ [17].

- Rigorous Diagnostic Accuracy Studies: Conducting studies that meet regulatory standards to demonstrate clinical utility for specific indications [12].

In conclusion, while the promise of microbiome-based diagnostics is immense, its path to clinical integration must be paved with rigorous science, standardized methods, and tempered expectations. This international consensus provides the essential roadmap, ensuring that the field develops in a manner that is reliable, reproducible, and ultimately, beneficial for patients.

The human microbiome, defined as the collective genome of the trillions of microorganisms inhabiting our bodies, has transitioned from being perceived as a mere collection of passengers to being recognized as a functional human organ that is integral to physiology and homeostasis. This complex ecosystem of bacteria, archaea, viruses, and eukaryotes exceeds the number of human cells, performing critical functions including immune regulation, breakdown of dietary compounds, production of essential nutrients, and protection against pathogens [18]. Groundbreaking developments in sequencing technologies and analytical methods have fundamentally advanced our understanding of the microbiome's structure and function, revealing its operation through intricate ecological principles [18].

This review synthesizes current conceptual frameworks for understanding the microbiome as a human organ and examines the ecological principles guiding its study and manipulation. We explore how these theoretical advances are being translated into validated analytical approaches and therapeutic strategies, with a particular focus on the emerging international consensus that is shaping the future of microbiome research and its clinical application. By integrating foundational concepts with cutting-edge ecological engineering and consensus-driven validation protocols, we aim to provide a comprehensive comparison of the frameworks and methodologies that are defining this rapidly evolving field.

Conceptual Frameworks for Understanding the Microbiome as an Organ

Systematic Theoretical Frameworks

A systematic framework proposed in Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy integrates knowledge from anatomy, physiology, immunology, histology, genetics, and evolution to reconceptualize the human-microbe relationship [19]. This framework introduces several key concepts that reframe our understanding of the microbiome's role in human biology. The "innate and adaptive genomes" concept enhances genetic and evolutionary understanding by distinguishing between the inherent human genetic blueprint (innate genome) and the dynamic, acquired microbial genes (adaptive genome) that together contribute to total host phenotypic variation [19].

The "germ-free syndrome" challenges the traditional view of "microbes as pathogens" by demonstrating through germ-free animal models that microorganisms are actually necessary for normal health and development [19]. The "slave tissue" concept posits a symbiotic relationship where microbes function as exogenous tissues under the regulation of human master tissues (nerve, connective, epithelial, and muscle tissues), highlighting the complex interplay between host systems and microbial communities [19]. Furthermore, the "acquired microbial immunity" framework positions the microbiome as an adjunct to the human immune system, providing a scientific rationale for probiotic therapies and judicious antibiotic use [19].

Table 1: Key Conceptual Frameworks for Understanding the Microbiome as a Human Organ

| Conceptual Framework | Key Principle | Implication for Research and Medicine |

|---|---|---|

| Innate & Adaptive Genomes | Distinguishes inherent human genes from acquired microbial genes | Expands understanding of host phenotypic variation and genetic diversity |

| Germ-free Syndrome | Demonstrates necessity of microbes for normal health | Challenges pathogen-centric view of microorganisms |

| Slave Tissue Concept | Frames microbes as exogenous tissues under host regulation | Elucidates symbiotic host-microbe control mechanisms |

| Acquired Microbial Immunity | Positions microbiome as immune adjunct | Supports rational probiotic and antibiotic use |

| Meta-host Model | Broadens host definition to include symbiotic microbes | Explains disease heterogeneity and transplantation outcomes |

Ecological and Evolutionary Frameworks

The reconceptualized 4 W framework for human microbiome acquisition provides a nuanced approach to understanding microbial transmission, particularly during early life [20]. This framework addresses the limitations of traditional "vertical versus horizontal" transmission models from infectious disease epidemiology by instead focusing on four key components: "what" (the transmitted microbial elements, including cells, structural elements, or metabolites), "where" (the source and destination sites), "who" (the source of the microbes, such as parents, household members, or the environment), and "when" (the timing of transmission events) [20]. This multifaceted framework more accurately captures the complexity of microbiome assembly across the human lifespan, particularly during critical developmental windows.

The "health-illness conversion model" encapsulates the interplay between innate and adaptive genomes and patterns of dysbiosis, providing a systematic way to understand how microbiome disturbances contribute to disease states [19]. Additionally, the "cell-microbe co-ecology model" describes the symbiotic regulation and co-homeostasis between microbes and human cells, emphasizing the dynamic balance that characterizes health [19]. These frameworks collectively position the microbiome not as a separate entity, but as an integrated physiological system that obeys ecological principles while being subject to host evolutionary pressures.

Ecological Principles Informing Microbiome Research

Translation of Macroecological Principles

Microbiome engineering efforts increasingly leverage principles from decades of macroecology research, particularly those governing the relationship between biodiversity and ecosystem function [21]. The translation of these ecological principles to microbiome engineering focuses on three critical stages: microbiome design, colonization, and maintenance [21]. A key insight from this translation is that many engineering efforts fail due to inadequate design principles that result in the loss of key microorganisms and disruption of functional links between the engineered community and its intended ecosystem service [21].

Niche theory, originally developed for macroecosystems, has proven particularly valuable for understanding and manipulating microbial communities in host-associated environments [21]. The ecological niche concept explains how microorganisms occupy specific functional roles and spatial locations within the host ecosystem, and how these niches can be manipulated to optimize community stability and function. This approach emphasizes the importance of niche dynamics in optimizing the diversity and abundance of microbial taxa to promote both stability and functionality, especially in therapeutic contexts [21].

Table 2: Ecological Principles Applied to Microbiome Engineering

| Ecological Principle | Source in Macroecology | Application to Microbiome Engineering |

|---|---|---|

| Biodiversity-Ecosystem Function | Tilman et al., 2014 [21] | Guides optimization of microbial diversity for desired therapeutic functions |

| Niche Theory | Hutchinson, 1957 [21] | Informs design of microbial communities with complementary functional roles |

| Succession Theory | Clements, 1936 [21] | Models ecological progression during microbiome assembly and manipulation |

| Stability-Diversity Relationship | MacArthur, 1955 [21] | Shapes communities resistant to perturbation and resilient to disturbance |

| Competitive Exclusion | Gause, 1930s (not in results) | Guides selection of compatible consortium members to enhance persistence |

Ecological Models for Microbiome Dynamics

The application of ecological principles has led to the development of specific models that capture the dynamics of host-microbiome systems. The "ecosystem on a leash" model conceptualizes the host microbiome as an ecosystem under host control mechanisms, illustrating the tension between microbial community self-organization and host regulation [21]. This model helps explain how host factors such as diet, immune responses, and physical niches shape the composition and function of microbial communities while still allowing for ecological processes to operate within constraints set by the host.

The emphasis on host physical niches highlights how anatomical and physiological features create distinct microbial habitats that maintain community composition and stability [21]. These physical niches—including the gastrointestinal crypt architecture, mucosal surfaces, and skin microenvironments—provide the structural foundation upon which ecological interactions between microbial taxa unfold. Understanding these physical determinants of community assembly is essential for effectively engineering microbiomes for therapeutic purposes, as they define the environmental parameters that support or inhibit particular microbial functions.

Analytical Methodologies and Consensus Approaches

Standardization of Microbiome Testing

An international consensus statement on microbiome testing in clinical practice has established a standardized framework for the development and application of microbiome-based diagnostics [7]. Developed through a Delphi process involving 69 experts from 18 countries, this consensus provides critical guidance on the appropriate use and interpretation of microbiome analyses [7] [14]. The consensus strongly emphasizes that microbiome testing should be initiated by licensed healthcare providers based on clinical rationale rather than through direct-to-consumer requests, which risk misinterpretation and inappropriate interventions [12].

Regarding analytical methodologies, the consensus recommends that appropriate modalities for gut microbiome community profiling include amplicon sequencing (e.g., 16S rRNA gene sequencing) and whole genome sequencing (shotgun metagenomics) [7] [14]. In contrast, techniques such as multiplex PCR and bacterial cultures, while potentially useful for specific pathogen detection, cannot be considered comprehensive microbiome testing methods and should not be used as proxies for microbiome profiling [7]. This distinction is crucial for ensuring that research and clinical practice employ methodologies capable of capturing the full complexity of microbial communities.

Methodological Standards and Reporting

The international consensus establishes minimum requirements for microbiome testing quality, emphasizing that providers must adhere to high-quality standards and maintain transparency about the current limited evidence for clinical applicability [7]. The consensus specifies that comprehensive taxonomic profiling should be reported with the deepest possible resolution, while commonly used but poorly validated metrics such as the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio should be excluded from clinical reports due to insufficient evidence supporting their clinical utility [14] [12].

Critical to the interpretation of microbiome data is the collection of detailed clinical metadata, including patient age, body mass index, diet, medications, and gut transit time, which provide essential context for understanding variations in microbiome composition and function [7] [14]. Additionally, the consensus strongly recommends that microbiome test reports include comparison to matched healthy control groups to facilitate meaningful interpretation of results [14]. Perhaps most significantly, the consensus states that post-testing therapeutic advice should remain the responsibility of the referring healthcare provider rather than the testing provider, reinforcing the need for clinical expertise in translating microbiome data into patient care [12].

Experimental Approaches and Research Methodologies

Validated Experimental Workflows

The following workflow diagram illustrates the standardized approach for microbiome analysis based on international consensus guidelines and ecological principles:

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

The following table details key research reagents and materials essential for conducting robust microbiome research according to consensus guidelines and ecological principles:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Microbiome Analysis

| Research Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Stool Collection Kit with DNA Stabilizer | Preserves microbial community structure during sample transport and storage | Must contain genome preservative; maintain stability at recommended time frames [7] |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Isolates high-quality microbial DNA from complex samples | Should be validated for diverse bacterial taxa; include mechanical lysis steps for tough Gram-positive species |

| 16S rRNA Gene Primers | Amplifies variable regions for amplicon sequencing | Target appropriate hypervariable regions (V3-V4); include barcodes for multiplexing [20] |

| Shotgun Metagenomic Library Prep Kits | Prepares sequencing libraries for whole-genome analysis | Should minimize host DNA amplification bias; optimized for low-biomass samples |

| Reference Databases | Enables taxonomic classification and functional assignment | Curated databases (e.g., Greengenes, SILVA, GTDB) for accurate taxonomic profiling [14] |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines | Processes sequencing data and calculates ecological metrics | Must generate alpha diversity (within-sample) and beta diversity (between-sample) measures [7] |

| Positive Control Communities | Validates sequencing and analysis workflow performance | Defined mock microbial communities with known composition and abundance |

Therapeutic Development Approaches

The development of microbiome-based therapeutics requires specialized methodologies that account for the unique properties of living microbial products. Several distinct therapeutic modalities have emerged, each with its own development pathway and technical requirements [22]. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) involves the transfer of minimally manipulated microbial communities from screened donors to recipients, primarily used for recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection but under investigation for other indications [22]. Live Biotherapeutic Products (LBP) are biological products containing defined live microorganisms, which may consist of single or multiple strains, developed under regulatory frameworks similar to traditional biologics [22].

Additional therapeutic approaches include Antimicrobial Peptides (AMPs), which are multifunctional peptides with targeted antibacterial effects, and phage therapy, which utilizes bacteriophages for precise targeting of pathogenic bacterial infections [22]. The development of these therapeutics requires interdisciplinary resources, professional experience, and state-of-the-art facilities capable of maintaining microbial viability throughout manufacturing and storage [22]. Each approach presents distinct challenges in quality control, potency assessment, and stability testing that must be addressed through specialized analytical methods developed specifically for live microbial products.

Comparative Analysis of Microbiome Conceptualization Approaches

Framework Integration and Complementarity

The various conceptual frameworks for understanding the microbiome as a human organ demonstrate significant complementarity when analyzed collectively. The systematic framework emphasizing "innate and adaptive genomes" [19] aligns well with the ecological principles of host-microbe coevolution [21], together providing a more comprehensive understanding of how host genetics and microbial ecology interact to influence health outcomes. Similarly, the "slave tissue" concept [19] finds operational expression in the "ecosystem on a leash" model [21], both capturing the dynamic tension between host control mechanisms and microbial community self-organization.

The 4 W transmission framework [20] enhances the "acquired microbial immunity" concept [19] by providing a structured approach to investigating how microbial exposures during critical developmental windows shape immune function across the lifespan. This integration of conceptual models with operational frameworks is essential for advancing from theoretical understanding to practical intervention strategies. Furthermore, the international consensus on microbiome testing [7] provides the necessary methodological standardization that enables robust comparison of findings across different research programs applying these conceptual frameworks.

Translational Applications and Therapeutic Development

The conceptualization of the microbiome as a human organ has direct implications for therapeutic development and clinical translation. The ecological principle that biodiversity supports ecosystem function [21] informs the design of microbial consortia for Live Biotherapeutic Products (LBPs), guiding selection of complementary strains with diverse functional attributes [22]. Similarly, the understanding of microbial niches [21] helps predict which introduced strains will persist in specific host environments and which functions they are likely to perform in different anatomical sites.

The international consensus statement establishes critical quality standards for developing these therapeutics, emphasizing the need for high-quality accredited laboratories, validated analytical methods, and comprehensive reporting [7] [14]. This consensus approach is particularly important for addressing the current limitations in evidence supporting routine clinical use of microbiome testing, while simultaneously building the methodological foundation needed to generate the robust evidence required for regulatory approval of microbiome-based diagnostics and therapies [7]. As the field advances, the integration of conceptual frameworks, ecological principles, and consensus standards will be essential for realizing the full potential of microbiome science to improve human health.

The conceptualization of the human microbiome as an organ represents a paradigm shift in human biology, with profound implications for understanding health and disease. The integration of systematic theoretical frameworks, ecological principles, and standardized analytical approaches provides a robust foundation for both basic research and therapeutic development. While significant challenges remain—particularly in establishing causal mechanisms and validating clinical utility—the convergence of these complementary perspectives promises to accelerate the translation of microbiome science into effective interventions for a wide range of diseases. As consensus standards mature and ecological principles are more effectively applied to microbial community engineering, the vision of harnessing the microbiome as a therapeutic target is increasingly becoming a clinical reality.

The human gut microbiome, a complex ecosystem of bacteria, viruses, fungi, and archaea, is increasingly recognized as a fundamental regulator of human health and disease. Recent advances in high-throughput sequencing technologies have revolutionized our understanding of microbial communities, revealing their crucial roles in metabolic regulation, immune function, and neurological development [23]. Despite exponential growth in basic science research, the clinical translation of microbiome discoveries remains markedly limited. A significant translational chasm exists between compelling research associations and validated clinical applications, creating a landscape filled with promising yet unproven diagnostic and therapeutic tools [7] [24]. This gap is particularly problematic given the proliferation of direct-to-consumer microbiome testing services that often outpace evidence-based validation [7].

The current evidence gaps span multiple domains, including insufficient standardization, limited causal understanding, and inadequate clinical trial validation. An international consensus statement on microbiome testing in clinical practice highlights that "there is currently limited evidence for the applicability of gut microbiome testing in clinical practice," directly cautioning against its routine use without stronger supporting studies [7] [14]. This review systematically examines these evidence gaps, compares current technological approaches, details experimental methodologies, and identifies the critical pathway forward for validating microbiome-based applications in clinical practice.

Current Evidence Gaps in Clinical Applications

Diagnostic and Therapeutic Limitations

Table 1: Key Evidence Gaps in Microbiome Clinical Applications

| Domain | Specific Gap | Clinical Implications | Current Consensus View |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic Applications | Lack of validated reference ranges for "healthy" microbiome | Inability to define dysbiosis thresholds for clinical diagnosis | "No common definition of dysbiosis is available at this point" [14] |

| Causality Establishment | Difficulty distinguishing causal from correlative relationships | Limited understanding of microbiome's role in disease pathogenesis | "Defining the exact nature of dysbiosis is essential for clinical and therapeutic applications" [25] |

| Methodological Standardization | Absence of unified protocols for sample collection, processing, and analysis | Limited reproducibility and comparability across studies | "Lack of standardized protocols, inconsistent reproducibility, complex data interpretation" [23] |

| Clinical Trial Validation | Insufficient interventional studies with clinical endpoints | Microbiome manipulation strategies lack evidence of efficacy | "Human trials are essential for establishing the efficacy of these interventions" [25] |

| Regulatory Frameworks | Absence of established pathways for microbiome-based diagnostic approval | Unregulated direct-to-consumer tests with unproven clinical value | "Absence of established regulations and framework for the clinical translation" [7] |

The clinical application of microbiome science faces fundamental challenges that span the entire translational pathway. A primary limitation is the absence of standardized diagnostic criteria for dysbiosis. Unlike traditional laboratory values with established reference ranges, microbiome composition exhibits substantial inter-individual variation influenced by age, diet, geography, medication use, and host genetics [24] [26]. This variability complicates the establishment of universal diagnostic thresholds. The international consensus statement explicitly notes that commonly used metrics like the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio "do not capture the variation in the gut microbiome within the same host and between hosts and there is insufficient evidence to establish a causal relationship between specific dysbiosis indices and host health" [14].

A second critical gap lies in establishing causality rather than correlation between microbiome profiles and disease states. While numerous studies have identified microbial signatures associated with conditions ranging from inflammatory bowel disease to neurological disorders, "determining the underlying mechanisms and establishing cause and effect is extremely difficult" [25]. This challenge is compounded by the fact that many microbiome-disease relationships may be bidirectional, with disease states simultaneously altering and being altered by microbial communities [25].

Methodological and Regulatory Challenges

The field also grapples with significant methodological heterogeneity that limits comparability across studies. Variations in sample collection methods, DNA extraction techniques, sequencing platforms, and bioinformatic analyses introduce substantial variability that confounds cross-study comparisons and meta-analyses [23]. The international consensus panel identified this as a major barrier, noting "methodological variability, incomplete functional annotation of microbial 'dark matter,' and underrepresentation of global populations" as key limitations [23].

Perhaps most importantly, there is a dearth of large-scale, prospective interventional trials demonstrating that microbiome-based diagnostics or therapies improve clinically meaningful endpoints. While mechanistic studies and association analyses abound, evidence from randomized controlled trials with patient-centered outcomes remains limited [7]. The consensus statement concludes that "at the present time, there is insufficient evidence to widely recommend the routine use of microbiome testing in clinical practice, which should be supported by dedicated studies" [7].

The regulatory landscape for microbiome-based applications remains underdeveloped, creating an environment where direct-to-consumer tests can proliferate without demonstrated clinical utility. This regulatory gap has allowed commercial entities to offer microbiome testing services that "often claims to drive the clinical management of patients with dysbiosis-associated diseases" despite limited evidence supporting these claims [7].

Comparative Analysis of Microbiome Testing Methodologies

Technical Approaches and Their Limitations

Table 2: Comparison of Microbiome Analysis Methodologies

| Method | Resolution | Primary Applications | Advantages | Limitations | Evidence Gap |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing | Genus to species level | Microbial community profiling, diversity assessment | Cost-effective, well-established protocols, standardized analysis pipelines | Limited taxonomic and functional resolution, primer bias | Inability to detect strain-level variation or functional capacity [23] |

| Shotgun Metagenomics | Species to strain level, functional genes | Comprehensive taxonomic profiling, functional potential assessment | Strain-level resolution, identification of non-bacterial members, functional gene content | Higher cost, computational demands, database limitations | Functional predictions not necessarily reflective of actual microbial activity [23] |

| Metatranscriptomics | Gene expression | Active microbial functions, response to interventions | Insights into microbial community activity rather than potential | Technical challenges with RNA stability, higher cost and complexity | Limited standardization, unclear how to interpret transcriptional changes clinically [27] |

| Metabolic Profiling | Metabolite level | Functional output of microbiome, host-microbe interactions | Direct measurement of functional molecules, integrative view | Difficulty distinguishing microbial vs host metabolites, dynamic fluctuations | Lack of reference ranges, uncertain clinical correlates [24] |

The choice of analytical methodology significantly influences the results and interpretation of microbiome studies. 16S rRNA gene sequencing remains the most widely used approach due to its cost-effectiveness and established bioinformatic pipelines. However, this method provides limited taxonomic resolution and no direct information about functional capacity [14]. The international consensus recommends either 16S rRNA sequencing or whole-genome sequencing for gut microbiome community profiling but notes that "multiplex PCR and bacterial cultures, although potentially useful, neither can be considered microbiome testing nor can be used as a proxy for microbiome profiling" [7].

Shotgun metagenomics provides higher taxonomic resolution and insights into functional potential by sequencing all genomic material in a sample. This approach has enabled the identification of specific microbial strains and functional pathways associated with conditions like inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer [23]. However, a significant evidence gap persists between predicting functional potential and demonstrating actual microbial activity, as "functional predictions not necessarily reflective of actual microbial activity" [23].

Emerging approaches like metatranscriptomics and metabolic profiling aim to bridge this gap by measuring RNA expression or metabolite production, respectively. These methods offer insights into the active functions of the microbial community but come with their own technical challenges and interpretive complexities [27]. The integration of these multi-omics approaches represents a promising direction but requires further standardization and validation.

Analytical Standardization Challenges

A critical evidence gap across all methodologies is the lack of analytical standardization. Differences in sample collection methods (including storage conditions and preservatives), DNA extraction techniques, sequencing platforms, and bioinformatic pipelines can all introduce significant variability that compromises reproducibility and cross-study comparability [7]. The international consensus emphasizes that "appropriate modalities for gut microbiome community profiling include amplicon sequencing and whole genome sequencing" but notes the importance of standardizing pre-analytical conditions [7].

Another limitation is the inadequate representation of global populations in reference databases. Most existing microbiome databases are skewed toward Western populations, limiting their applicability to diverse ethnic and geographic groups [23]. This representational bias may obscure important microbial signatures relevant to different populations and compromise the generalizability of findings.

Experimental Protocols for Validating Clinical Applications

Establishing Causal Relationships

Figure 1: Framework for Establishing Microbiome-Disease Causality

Overcoming the correlation-causation gap requires rigorous experimental approaches. The scientific consensus emphasizes that "preclinical models, including germ-free animals, organoids and ex vivo systems, are essential tools to understand the functional role of host-microbiome interactions" but notes they "require improved standardization and translational relevance" [25]. The following protocols represent current best practices for establishing causal relationships:

Gnotobiotic Mouse Models Protocol:

- Animal Preparation: Maintain germ-free mice in sterile isolators to prevent unintended microbial colonization.

- Microbial Inoculation: Introduce human-derived microbial communities via fecal microbiota transplantation from well-characterized donors (healthy vs diseased).

- Phenotypic Monitoring: Assess disease-relevant phenotypes through physiological, metabolic, and immunological parameters.

- Mechanistic Investigation: Utilize multi-omics approaches to identify specific microbial taxa, genes, or metabolites driving observed phenotypes.

- Interventional Validation: Test hypotheses through targeted microbial interventions (specific probiotics, prebiotics, or faecal microbiota transplantation).

This approach has been instrumental in demonstrating causal roles for the microbiome in conditions like hypertension, where "fecal microbiota transplantation from hypertensive donors to germ-free mice can directly elevate blood pressure" [26]. However, limitations remain in translating findings from mouse models to human applications due to physiological differences and simplified microbial communities.

Human Intervention Trial Protocol:

- Participant Stratification: Recruit well-characterized participant groups based on clinical phenotypes, and consider microbiome composition if validated stratification biomarkers exist.

- Intervention Design: Implement targeted microbiome interventions (dietary modification, probiotics, prebiotics, or faecal microbiota transplantation) with appropriate control groups.

- Multi-omics Profiling: Collect longitudinal samples for comprehensive microbiome analysis (16S rRNA, metagenomics, metabolomics) alongside clinical metadata.

- Clinical Endpoint Assessment: Measure predefined clinical endpoints relevant to the condition under investigation.

- Integration Analysis: Apply advanced computational methods to identify associations between microbiome changes and clinical outcomes.

Recent trials exemplifying this approach include the ADDapt trial, which demonstrated that "emulsifier dietary restriction reduces symptoms and inflammation in patients with active Crohn's disease" [28], and the Be GONE Trial, which found that "adding navy beans to the usual diet was a safe, scalable dietary strategy to favorably modulate the gut microbiome of patients with obesity and a history of colorectal cancer" [28].

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Approaches

Figure 2: AI-Driven Microbiome Analysis Workflow

Advanced computational approaches are increasingly employed to navigate the complexity of microbiome data. Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) techniques "enable the discovery of non-invasive microbial biomarkers, refined risk stratification, and prediction of treatment response" [27]. Key methodological considerations include:

Data Preprocessing Protocol:

- Quality Control: Filter sequences based on quality scores, remove chimeras, and correct for sequencing depth variations.

- Normalization: Apply appropriate normalization methods to account for compositionality of microbiome data.

- Feature Engineering: Select biologically relevant features (taxa, genes, pathways) while reducing dimensionality.

Predictive Modeling Protocol:

- Algorithm Selection: Choose appropriate ML algorithms based on data characteristics and research question (Random Forest for classification, regression for continuous outcomes).

- Cross-Validation: Implement rigorous cross-validation strategies to avoid overfitting.

- Interpretation: Apply explainable AI (xAI) approaches like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) to identify features driving predictions.

These approaches have shown promise in areas like inflammatory bowel disease, where "omics-based signatures have been shown to be a diagnostic marker of IBD to differentiate between CD and UC" [27]. However, limitations persist regarding "data variability, the lack of methodological standardization, and challenges in clinical translation" [27].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Microbiome Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | QIAamp PowerFecal Pro Kit, DNeasy PowerSoil Kit | Efficient lysis of diverse microbial cells, inhibitor removal | Critical for data comparability; extraction method significantly impacts results [7] |

| Storage/Preservation Solutions | DNA/RNA Shield, RNAlater | Stabilize microbial community composition between collection and processing | Preservation method affects DNA yield and community representation [7] |

| Sequencing Standards | ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standards, NIST stool reference materials | Quality control, cross-study comparability | Enable assessment of technical variability and methodological biases [23] |

| Cell Culture Media | Brain Heart Infusion broth, YCFA medium | Cultivation of fastidious anaerobic gut bacteria | Essential for moving beyond sequencing to functional validation [25] |

| Gnotobiotic Animal Models | Germ-free mice, Humanized microbiota mice | Establishing causality in host-microbiome interactions | Require specialized facilities and expertise [25] |

| Multi-omics Assays | Metabolomics kits, Proteomics platforms | Integrative analysis of microbiome function | Technical variability requires careful standardization [27] |

The reliability and reproducibility of microbiome research depend critically on standardized reagent systems. The international consensus emphasizes that "providers of microbiome testing should communicate a reasonable, reliable, transparent, and scientific representation of the test" and adhere to high-quality standards [7]. Several key reagent categories deserve particular attention:

DNA Extraction Kits specifically designed for complex stool samples are essential for obtaining representative microbial DNA. Different extraction methods can significantly impact the apparent community composition due to varying efficiency in lysing different bacterial taxa [7]. The consensus recommends that "the report should briefly detail the test protocol, including methods of stool collection and storage, DNA extraction, amplification, sequencing, and post-sequencing analyses" to enable proper interpretation [7].

Reference Materials such as mock microbial communities with known composition are critical for quality control and cross-study comparisons. Initiatives like the NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology) stool reference material help standardize methodology across laboratories [23]. The use of such standards allows researchers to distinguish technical artifacts from true biological signals.

Specialized Culture Media enabling the growth of previously uncultivated microbes represents an advancing frontier. Moving from sequencing-based observations to functional validation requires the ability to culture and manipulate specific microbial strains [25]. Recent advances in culturomics have expanded the range of cultivable gut bacteria, opening new avenues for mechanistic studies.

The field of microbiome research stands at a critical juncture, with compelling associative data outpacing validated clinical applications. Significant evidence gaps persist in diagnostic standardization, causal understanding, and clinical trial validation. Overcoming these limitations requires coordinated efforts across multiple domains: standardization of analytical methods, development of robust reference materials, implementation of rigorous experimental designs establishing causality, and execution of well-controlled clinical trials with meaningful endpoints.

The international consensus statement provides a framework for this progression, emphasizing that "before microbiome tests become integrated into clinical practice, microbiome science must shift from descriptive to mechanistic approaches involving host physiology features and control for confounders that hinder the causal connection with human diseases" [14]. Future research priorities should include large-scale longitudinal studies, diverse population representation, standardized multi-omics protocols, and development of interpretative frameworks that translate microbial measurements into clinically actionable information.

As the field matures, the integration of artificial intelligence with multi-omics data and rigorous experimental validation offers promise for bridging the current evidence gaps. However, this will require interdisciplinary collaboration among microbiologists, clinicians, computational biologists, and regulatory scientists to ensure that microbiome-based applications meet the rigorous standards required for clinical implementation. Only through such coordinated efforts can the tremendous potential of microbiome science be responsibly translated into meaningful clinical applications that improve patient care.

This guide provides a comparative analysis of the core concepts shaping contemporary microbiome research: dysbiosis, core microbiome, and keystone species. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the methodologies to define and measure these concepts is crucial for validating microbiome analysis approaches and developing targeted therapies. We objectively compare the performance of different definitions, analytical techniques, and biomarkers used to quantify these states, supported by experimental data from recent studies and clinical trials. The synthesis presented here aims to inform the selection of appropriate models and metrics for consensus approach validation in microbiome research.

The complex ecosystem of microorganisms inhabiting the human body, particularly the gut, profoundly influences host health through metabolic regulation, immune modulation, and maintenance of ecological balance [29] [25]. Three fundamental concepts form the cornerstone of microbial-host interaction research: dysbiosis refers to a disruption of the microbial community structure associated with disease; the core microbiome represents the set of microbial taxa or functions consistently present in healthy individuals; and keystone species are highly influential taxa whose impact on ecosystem stability is disproportionate to their abundance [29] [30] [31]. These concepts are intrinsically linked, as keystone species often carry out essential functions that contribute to a healthy core microbiome, and their loss can be a driving factor in dysbiosis [31]. The field is moving beyond simple taxonomic classification toward functional and strain-resolved analyses to better understand the mechanisms governing host health [32]. This evolution reflects the growing consensus that microbial community function, rather than mere composition, ultimately determines host physiological outcomes.

Comparative Analysis of Dysbiosis Indexes and Measurement Approaches

Dysbiosis is an imbalance in the gut microbial community that has been associated with numerous gastrointestinal, metabolic, and neurological disorders [33] [25]. However, due to high inter-individual variability in healthy microbiomes, no single gold standard for defining dysbiosis exists. Instead, researchers have developed various dysbiosis indexes, each with distinct methodologies, strengths, and limitations, suited to different research or clinical contexts [33]. The table below compares five primary categories of dysbiosis indexes.

Table 1: Comparison of Dysbiosis Index Methodologies

| Index Category | Description | Representative Indexes | Disease/Condition Application | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large-Scale Bacterial Marker Profiling | Uses a predefined set of bacterial markers (e.g., 54 probes covering 300+ markers) to calculate a dysbiosis score [33]. | GA-map Dysbiosis Index [33] | Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS), Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) [33] | Standardized, commercially available; provides a simple numerical score. | Proprietary calculation method; may not capture cohort-specific variations. |

| Relevant Taxon-Based Methods | Calculates ratios or formulas based on specific taxa known to be altered in a given condition [33]. | Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio [33]; MHI-A [34] | Obesity, Liver Cirrhosis, Post-Antibiotic Dysbiosis [34] [33] | Intuitively simple to calculate and interpret; hypothesis-driven. | Oversimplifies complex communities; ratios can be misleadingly compositional. |

| Neighborhood Classification | Measures the distance (e.g., Bray-Curtis) between a test sample and a reference set of healthy samples [33]. | Median Bray-Curtis to Healthy Reference [33] | Ulcerative Colitis, Crohn's Disease [33] | Holistic, captures overall community structure difference. | Highly dependent on the choice and size of the reference cohort. |

| Random Forest Prediction | Machine learning models trained to classify samples as dysbiotic or healthy based on microbiome features [33]. | Random Forest Classifiers [33] [32] | Various, including Colorectal Cancer [32] | Handles complex, high-dimensional data well; can identify novel biomarkers. | "Black box" nature; requires large, well-curated training datasets. |

| Combined Alpha-Beta Diversity | Integrates measures of within-sample (alpha) and between-sample (beta) diversity [33]. | Alpha-Beta Diversity Combined Index [33] | General dysbiosis assessment | Captures multiple ecological dimensions of the microbial community. | Complex to interpret clinically; lacks universal thresholds for dysbiosis. |

Experimental Protocol: Validating a Microbiome Health Index for Post-Antibiotic Dysbiosis

The Microbiome Health Index for post-Antibiotic dysbiosis (MHI-A) is a relevant taxon-based index developed to specifically distinguish post-antibiotic dysbiosis from a healthy microbiota state [34]. Its development and validation offer a template for a robust methodological approach.

- Objective: To develop a univariate biomarker capable of differentiating a dysbiotic, post-antibiotic gut microbiome from a healthy one [34].

- Data Sources: Longitudinal gut microbiome data from participants in Phase II and III clinical trials of RBX2660 and RBX7455 (investigational Live Biotherapeutic Products for recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection, rCDI). Pre-treatment samples represented post-antibiotic dysbiosis, while the therapeutic doses themselves, manufactured from healthy donors, represented the healthy state [34].

- Algorithm Derivation: Dirichlet-multinomial recursive partitioning (DM-RPart) was used to identify taxonomic classes that most strongly separated baseline (dysbiotic) and post-treatment (restored) samples. Four classes were identified: Gammaproteobacteria and Bacilli were dominant in dysbiosis, while Bacteroidia and Clostridia were dominant in healthy/restored states. A multivariate logistic regression model determined the optimal formula was the ratio of (

Bacteroidia + Clostridia) to (Gammaproteobacteria + Bacilli), termed the MHI-A [34]. - Validation: The diagnostic utility of MHI-A was tested using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis, showing high accuracy in distinguishing dysbiotic and healthy states in the PUNCH CD2 trial. Validation was reinforced with public data from healthy or antibiotic-treated populations, showing MHI-A values were consistent across healthy cohorts and significantly shifted by microbiota-disrupting antibiotics [34].

Figure 1: MHI-A Calculation Workflow. This diagram outlines the key steps for calculating the Microbiome Health Index for post-Antibiotic dysbiosis from raw sequencing data.

Defining the Core Microbiome: From Taxonomy to Function

The "core microbiome" has historically been defined as the set of microbial taxa common to all or most healthy individuals. However, large-cohort studies like the Human Microbiome Project (HMP) revealed that no universal taxonomic core exists due to immense inter-individual variation influenced by diet, genetics, and geography [32]. This has prompted a paradigm shift from a taxonomy-based to a function-based definition of the core microbiome.

The Evolving Definition of "Core"

- Traditional View: Focused on the abundance of specific taxa (e.g., Bacteroides, Faecalibacterium) and metrics like microbial diversity or the Firmicutes-to-Bacteroidetes ratio. These have proven unreliable as universal health indicators, as they are strongly influenced by non-health factors like diet [32].

- Modern View: Emphasizes the preservation of core microbial functions essential for host health, rather than the specific species carrying them out. A promising framework is the "Two Competing Guilds" (TCGs) model, which posits that a healthy microbiome is characterized by a balance between a guild of microbes performing beneficial functions (e.g., fiber fermentation, butyrate production) and a guild enriched in virulence factors and antibiotic resistance genes [32]. The balance between these functional groups may serve as a more robust biomarker for health than taxonomic composition alone.

The HACK Index: A Novel Functional Ranking of Taxa

A significant recent advancement is the development of the Health-Associated Core Keystone (HACK) index [35]. This index moves beyond mere presence/absence by ranking 201 taxa based on their association strengths with:

- Prevalence and co-occurrence patterns in non-diseased subjects.

- Longitudinal stability within individuals.

- Overall host health status [35].

Derived from a meta-analysis of 45,424 gut microbiomes across 141 study cohorts, the HACK index is reproducible across different sequencing methods and cohort lifestyles. Consortia of high HACK-index taxa have been shown to respond positively to interventions like the Mediterranean diet and to reflect responsiveness to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy, providing a rational basis for designing microbiome-based therapeutics [35].

Keystone Species: The Pivotal Players in Microbial Ecosystems

In ecology, a keystone species is an organism that has a disproportionately large effect on its environment relative to its abundance. The term, coined by Robert Paine after his work with Pisaster sea stars, describes species that are crucial for maintaining the structure and stability of their ecosystem [30] [31]. Their removal triggers a cascade of effects that can drastically alter the ecosystem and reduce biodiversity [30].

Roles of Keystone Species Across Ecosystems

Keystone species can exert their influence through various mechanisms, illustrated in the following diagram and table.

Figure 2: Keystone Species Roles. This diagram categorizes the primary ecological roles played by keystone species and their downstream effects on the ecosystem.

Table 2: Keystone Species in the Human Gut Microbiome

| Keystone Species | Proposed Function | Method of Identification | Disease Association |

|---|---|---|---|

| Akkermansia muciniphila | Mucin degradation, gut barrier integrity [31] | Empirical culture-based studies [31] | Depleted in intestinal inflammation, obesity, and metabolic diseases [31] |

| Faecalibacterium prausnitzii | Butyrate production, anti-inflammatory effects [31] | Presence/absence correlation in cohorts [31] | Depleted in Crohn's disease and Ulcerative Colitis [31] |

| Christensenella minuta | Stimulates ecosystem diversity, acetate production [31] | Co-occurrence network analysis and empirical validation [31] | Associated with lean phenotypes; depleted in obesity and Crohn's disease [31] |

| Ruminococcus bromii | Key degrader of resistant starch; butyrate producer [31] | Empirical studies on starch degradation [31] | Highly prevalent in healthy individuals [31] |

| Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron | Degradation of complex dietary carbohydrates [31] | Empirical studies on carbohydrate metabolism [31] | Controversial and unclear association with IBD [31] |

Experimental Workflow for Identifying Keystone Species

Identifying keystone species requires a combination of advanced bioinformatic analyses and empirical validation.

- Step 1: Metagenomic Sequencing and Metabolomic Profiling. Shotgun metagenomic sequencing of cohort samples is performed to achieve strain-level resolution. This is increasingly paired with metabolomic profiling of stool and serum to link microbial genes to functional outputs [32].

- Step 2: Network Analysis. Co-occurrence and co-abundance networks are constructed from the microbial abundance data. Keystone taxa are identified as highly connected "hubs" within these networks, indicating a central role in the microbial community structure irrespective of their abundance [29] [31].

- Step 3: Functional Annotation. Metagenomic data are annotated using databases like KEGG and MetaCyto to predict the metabolic capabilities of identified keystone hubs, highlighting functions like butyrogenesis or bile acid metabolism [29].

- Step 4: In Vivo Validation. The causal role of candidate keystone species is tested using gnotobiotic mouse models (germ-free animals colonized with defined microbial communities). The impact of adding or removing the candidate species on community structure and host phenotype is assessed to confirm its keystone status [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Models

This section details key reagents, tools, and models essential for research into dysbiosis, core microbiome, and keystone species.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Microbiome-Host Interaction Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Gnotobiotic Mice | Causality testing; animals raised germ-free and then colonized with defined human microbial communities to study host-microbiome interactions [25]. | Humanized Microbiota-Associated (HMA) mice are a key model for validating keystone species function and studying dysbiosis mechanisms [25]. |

| Organoids & Gut-on-a-Chip | Ex vivo models for studying host-microbiome interactions at the cellular level, including epithelial barrier function and immune responses [25]. | Lack full physiological context but useful for mechanistic studies and personalized therapy development [25]. |

| Live Biotherapeutic Products (LBPs) | Investigational products containing live organisms (e.g., RBX2660) to correct dysbiosis; used as tools to understand microbial restoration [34]. | Provide a defined intervention to test hypotheses about core microbiome restoration and keystone species reintroduction. |

| Multi-Omics Integration Platforms | Combining metagenomics, metabolomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics to connect microbial community activity with host biological responses [32]. | Essential for moving beyond correlation to mechanism; a cornerstone of the HMP2 [32]. |

| Batch Effect Correction Algorithms | Computational tools to remove technical noise from multi-cohort microbiome data, enabling robust meta-analyses [36]. | Methods like ConQuR (Conditional Quantile Regression) are critical for large-scale, reproducible biomarker discovery [36]. |

| AI-Based Causal Inference Tools | Machine learning algorithms to elucidate complex, non-linear associations and infer causality between microbial features and health outcomes [32]. | Helps overcome limitations of traditional statistical methods (e.g., Mendelian randomization) when dealing with complex microbiome datasets [32]. |

The validation of a consensus approach in microbiome analysis hinges on a nuanced understanding of dysbiosis, the core microbiome, and keystone species. The field is rapidly evolving from descriptive, taxonomy-based assessments toward functional, mechanistic, and causal insights. The development of robust indexes like MHI-A and HACK, alongside advanced analytical tools and preclinical models, provides the much-needed framework for this transition. For researchers and drug developers, the future lies in integrating strain-resolved multi-omics data, cross-cohort validation, and AI-driven causal inference to identify universally applicable biomarkers and therapeutic targets. This integrated approach will ultimately power the development of effective, microbiome-based precision medicines.

Analytical Pipelines in Practice: From Sequencing Technologies to Clinical Applications