Validating Microbiome Biomarkers for Clinical Diagnostics: From Cohort Studies to Clinical Implementation

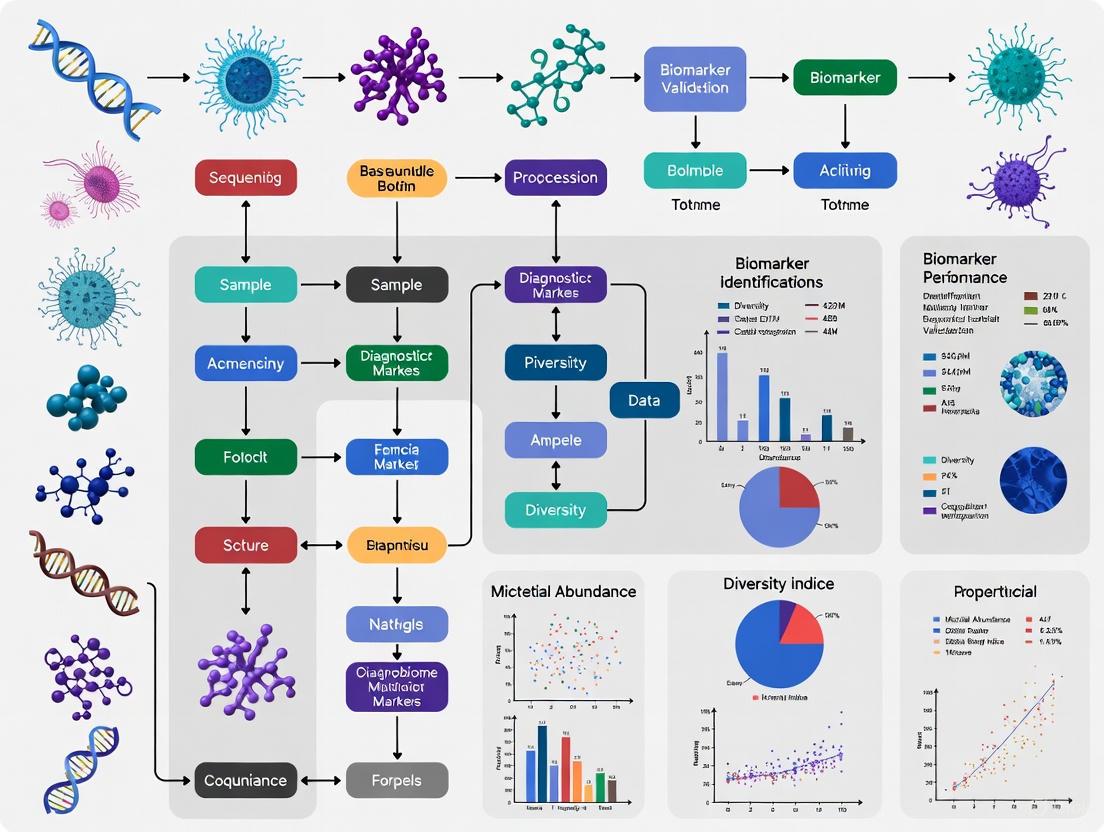

This comprehensive review examines the critical pathway for validating microbiome-based diagnostic biomarkers across diverse disease contexts.

Validating Microbiome Biomarkers for Clinical Diagnostics: From Cohort Studies to Clinical Implementation

Abstract

This comprehensive review examines the critical pathway for validating microbiome-based diagnostic biomarkers across diverse disease contexts. We explore the foundational evidence linking microbial signatures to diseases like colorectal cancer, IBD, and lung cancer, while addressing key methodological challenges in multi-omics integration, batch effect correction, and cohort study design. The article provides strategic frameworks for troubleshooting validation studies and compares emerging computational approaches for robust biomarker identification. By synthesizing evidence from large-scale validation cohorts and cross-study integrations, we outline a roadmap for translating microbial signatures into clinically viable diagnostic tools that could revolutionize precision medicine and early disease detection.

The Microbiome as a Diagnostic Frontier: Establishing Biological Plausibility and Clinical Associations

The traditional pathogen-centric model of disease is increasingly inadequate for understanding complex chronic illnesses. This guide compares the established pathogen model against the emerging holobiont theory, which considers the host and its entire microbial community as a single ecological unit. We objectively evaluate their performance through the lens of contemporary microbiome biomarker diagnostic validation cohort studies, providing experimental data and methodologies that are critical for researchers and drug development professionals. The analysis reveals that incorporating pathobiont dynamics and holobiont-system-level insights significantly improves diagnostic accuracy and predictive power for a range of diseases, from inflammatory conditions to neurodevelopmental disorders.

The concept of the holobiont—a host organism plus all its symbiotic microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, and viruses—is reshaping fundamental concepts in human biology and disease [1]. This framework challenges the binary classification of microbes as purely "good" or "bad," introducing the critical concept of the pathobiont.

Unlike traditional pathogens, pathobionts are potentially beneficial microbes that can, under specific environmental conditions, contribute to disease [2]. The holobiont model posits that disease often results from ecosystem dysbiosis, where a shift in the microbial community structure and function leads to a loss of beneficial microbes, an expansion of pathobionts, and a breakdown in host-microbe homeostasis. This paradigm shift has profound implications for diagnostic strategies and therapeutic development.

Model Comparison: Pathogen-Centric vs. Holobiont-Based Diagnostics

The following analysis compares the diagnostic and predictive performance of the traditional pathogen model against the holobiont framework, based on cross-cohort validation studies.

Table 1: Diagnostic Model Performance Across Disease Categories

| Disease Category | Diagnostic Approach | Intra-Cohort Validation AUC (Mean) | Cross-Cohort Validation AUC (Mean) | Key Strengths & Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intestinal Diseases (e.g., CD, UC, CRC) | Pathogen-Centric | ~0.77 | Low (Except specific pathogens) | Limited to known etiological agents. |

| Holobiont (Microbiome Biomarkers) | ~0.77 | ~0.73 | Superior cross-cohort generalizability for prescreening. | |

| Autoimmune Diseases (e.g., MS, RA) | Pathogen-Centric | Variable | Very Low | Fails to capture complex, multi-factorial etiology. |

| Holobiont (Microbiome Biomarkers) | ~0.77 | Low to Moderate | Promising for stratification; performance improved by combined-cohort modeling. | |

| Mental/Nervous System Diseases (e.g., ASD, AD, PD) | Pathogen-Centric | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Lacks a defined pathogenic basis for most disorders. |

| Holobiont (Microbiome Biomarkers) | ~0.77 | Low to Moderate | Provides novel, actionable biological insights where previous models failed. | |

| Graft-versus-Host Disease | Pathogen-Centric | Limited | Limited | Focuses on subsequent infections, not GVHD pathogenesis. |

| Holobiont (Microbiome Biomarkers) | N/A | N/A | Predictive of severity via loss of diversity and pathobiont expansion (e.g., Enterococcus) [3]. |

Key Insights from Comparative Data:

- Holobiont models match or exceed traditional models in intra-cohort validation, with AUCs around 0.77 [4].

- Cross-cohort validation, the gold standard for robustness, reveals the holobiont model's superior generalizability for intestinal diseases (AUC ~0.73) [4].

- For non-intestinal diseases, single-cohort microbiome classifiers perform poorly in cross-cohort validation. However, combined-cohort classifiers, which aggregate data from multiple studies, significantly improve performance, indicating that larger, more diverse datasets are key to robust holobiont-based diagnostics [4].

- The holobiont model provides value beyond diagnosis, offering mechanistic insights and predictive power for disease course and treatment response, as seen in GVHD and Multiple Sclerosis [2] [3].

Experimental Validation: Key Protocols and Workflows

Translating the holobiont theory into actionable diagnostics requires robust experimental protocols. Below are detailed methodologies from seminal studies.

Protocol 1: GWAS of the Plant Holobiont for Disease Resistance

This protocol from a pea root rot study [5] identifies how host genetics shape the microbiome to influence disease resistance.

Table 2: Key Reagents for Plant Holobiont GWAS

| Research Reagent / Solution | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| 252 Diverse Pea Lines | Provides genetic diversity for genome-wide association studies (GWAS). |

| Naturally Infested Soil | Serves as a consistent, complex source of soil-borne pathogens for phenotyping. |

| Genotyping-by-Sequencing (GBS) | A high-throughput method for discovering and genotyping thousands of SNP markers across the pea genome. |

| PacBio (Sequel II) & Illumina MiSeq | Platforms for sequencing the fungal ITS region and bacterial 16S rRNA gene, respectively. |

| UNOISE & DADA2 Pipelines | Bioinformatics tools for error-correcting and clustering sequences into operational taxonomic units (OTUs). |

| Zhongwang 6 Reference Genome | Used for aligning sequence reads and calling genetic variants. |

Experimental Workflow:

- Plant Cultivation and Phenotyping: Grow 252 diverse pea lines in naturally infested soil and sterile control soil under controlled conditions for 21 days. Assess disease symptoms using a Root Rot Index (RRI) and measure shoot dry weight [5].

- Host Genotyping: Extract DNA from one plant per line. Perform Genotyping-by-Sequencing (GBS). Align sequences to a reference genome ("Zhongwang 6") and call Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs). Filter for quality, resulting in 18,267 markers [5].

- Microbiome Profiling:

- Fungal Communities: Amplify the entire ITS region from root DNA using ITS1f/ITS4 primers. Sequence on a PacBio Sequel II system. Cluster sequences into OTUs and assign taxonomy using the UNITE database.

- Bacterial Communities: Amplify the V3-V4 regions of the 16S rRNA gene. Sequence on an Illumina MiSeq platform. Call amplicon sequence variants and assign taxonomy using the SILVA database [5].

- Holobiont Genetic Analysis:

- Perform a Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) using host SNP markers, with the abundance of microbial OTUs as phenotypic traits.

- Identify Quantitative Trait Loci (QTLs) in the plant genome that are significantly associated with the abundance of specific microbes.

- Use Genomic Prediction models to compare the power of host QTLs versus microbial OTU abundances for predicting root rot resistance [5].

Protocol 2: Validating Microbial Drivers of Neurodevelopment

This protocol [6] demonstrates a bedside-to-bench approach to validate a specific pathobiont's causal role in a neurodevelopmental disorder.

Experimental Workflow:

- Human Cohort Observation: Conduct a pilot clinical study using Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) in children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Observe that a reduction in Clostridium innocuum correlates with clinical improvement [6].

- Bacterial Strain Isolation: Islect C. innocuum strains from both ASD donors and neurotypical (NT) controls.

- Gnotobiotic Animal Modeling:

- Use the BTBR T+ tf/J mouse, an idiopathic ASD model that exhibits social deficits under specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions but not in the germ-free (GF) state.

- Monocolonize GF BTBR mice with either ASD-derived or NT-derived C. innocuum strains at different developmental windows (gestation, early life, post-weaning, adulthood) [6].

- Phenotypic and Mechanistic Analysis:

- Assess offspring for social behavior (e.g., three-chamber test) and repetitive behaviors.

- Analyze the neonatal brain metabolome (e.g., neurotransmitters, succinate levels).

- Examine microglial morphology and gene expression via immunohistochemistry and RNA sequencing [6].

The Pathobiont Switch: A Core Signaling Pathway

A key mechanistic insight from the holobiont model is the context-dependent functionality of microbes. The same microbe can act as a symbiont or a pathobiont based on the host's internal environment [2].

Table 3: Factors Influencing the Pathobiont Switch

| Factor | Pro-Symbiont Effect | Pro-Pathobiont Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Inflammation | Low, controlled inflammation (e.g., from tissue repair). | High, chronic inflammation creates a selective pressure for pathobionts [2]. |

| Diet | High-fiber, phytoestrogen-rich diets support SCFA-producing symbionts [2]. | Western-style diets can promote pro-inflammatory microbial metabolites. |

| Host Genetics | HLA and other immune alleles that support microbial diversity. | MS-associated HLA alleles linked to dysbiosis and neuroinflammation [2]. |

| Pharmacotherapy | Targeted therapies, pre/probiotics. | Broad-spectrum antibiotics deplete symbionts, allowing pathobiont blooms [3] [1]. |

| Environmental Exposures | Toxicants like glyphosate can induce dysbiosis [2]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successfully implementing holobiont research requires specific tools and reagents. The following table details essential items derived from the featured experimental protocols.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Holobiont Studies

| Reagent / Solution | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Gnotobiotic Mouse Models | Essential for establishing causality. Allows colonization of germ-free animals with defined microbial communities to study their specific functional impact [6]. |

| Human HLA Class II Transgenic Mice | Models to study how human genetic variations (a major risk factor for autoimmune disease) shape the microbiome and immune responses [2]. |

| Defined Microbial Consortia | Mixtures of specific bacterial strains (e.g., 15-strain consortia) used to test synergistic functions and as potential next-generation live biotherapeutics [1]. |

| Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) | An undefined, complex live biotherapeutic product used to restore a dysbiotic ecosystem to a healthy state in model systems and humans [1] [6]. |

| PacBio Long-Read & Illumina Short-Read Sequencers | Complementary sequencing technologies. PacBio is ideal for full-length 16S/ITS sequencing, while Illumina is suited for shallow-depth, high-throughput studies [5]. |

| 16S rRNA (V3-V4) & ITS Primers | Standard primer sets for amplifying bacterial and fungal genomic regions, respectively, for taxonomic profiling of microbial communities [5]. |

| UNITE & SILVA Databases | Curated reference databases for taxonomic classification of fungal (UNITE) and bacterial (SILVA) amplicon sequences [5]. |

The evidence from cross-cohort validation studies, GWAS of plant and animal holobionts, and mechanistic pathobiont research compellingly argues for a paradigm shift. The holobiont model, which integrates host genetics, microbial ecology, and pathobiont dynamics, provides a more robust framework for understanding disease etiology than the traditional pathogen-centric view.

While challenges remain—particularly in standardizing methodologies and improving cross-cohort generalizability for non-intestinal diseases—the integration of holobiont principles into diagnostic and drug development pipelines is no longer speculative. It is a necessary evolution for addressing the complexity of human disease in the 21st century. The experimental data and protocols outlined in this guide provide a foundation for researchers and drug developers to build upon, paving the way for Microbiome First Medicine and personalized, ecology-based therapeutic interventions [1].

The human microbiome has emerged as a critical modulator of human health and disease, with particular significance in oncology. Among various microbial inhabitants, Fusobacterium nucleatum (F. nucleatum), an anaerobic, Gram-negative bacterium, has transitioned from being regarded solely as an oral commensal to a potential oncobacterium associated with multiple cancer types [7]. Its enrichment in colorectal cancer (CRC) tissues has established it as a key subject in cancer microbiome research, but emerging evidence suggests its influence extends to other malignancies across anatomical boundaries [7]. This review synthesizes current understanding of F. nucleatum's role as a consistent microbial signature in CRC and other cancers, focusing on its pathogenic mechanisms, clinical implications, and potential as a diagnostic and therapeutic target. We objectively compare experimental data across studies and provide detailed methodologies to facilitate research reproducibility and biomarker validation in cohort studies.

Molecular Mechanisms ofFusobacterium nucleatumin Carcinogenesis

Adhesion and Invasion Mechanisms

Fusobacterium nucleatum initiates host-cell interaction through specific adhesins that facilitate attachment and invasion. The FadA adhesin binds directly to E-cadherin on epithelial cells, activating β-catenin signaling and driving oncogenic responses [7]. This interaction promotes cell proliferation and survival, positioning F. nucleatum as an active facilitator of malignant transformation [7]. Additionally, the Fap2 adhesin recognizes Gal-GalNAc overexpressed in colorectal cancer cells, enabling bacterial accumulation in tumor tissues [8]. These molecular interactions provide tropism mechanisms explaining F. nucleatum's enrichment in tumor microenvironments.

Immune Modulation and Inflammation

F. nucleatum significantly shapes the tumor immune microenvironment to favor cancer progression. It activates TLR4 signaling, leading to NF-κB activation and subsequent upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-17A, and TNF-α [9]. This inflammatory cascade establishes a chronic inflammatory state conducive to tumor growth. Furthermore, F. nucleatum recruits myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and modulates tumor-associated immune populations by suppressing cytotoxic activity to foster an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment [9]. The bacterium also binds to Siglec-7 receptors on natural killer (NK) cells, thereby suppressing NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity against cancer cells [7].

Metabolic Reprogramming and Treatment Resistance

Recent evidence indicates F. nucleatum induces metabolic changes that promote cancer progression and treatment resistance. The bacterium shifts central carbon metabolism in tumor cells and promotes CRC cell invasion [8]. It also reduces m6A modification in CRC cells, enhancing their invasiveness [8]. Through the establishment of a pro-inflammatory and immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment that promotes metastasis and facilitates DNA damage, F. nucleatum enhances the tumor's susceptibility to the development of chemoresistance [9]. Transcriptomic analyses of F. nucleatum-infected CRC cells reveal activation of multiple chemoresistance-associated pathways, including those driving inflammation, immune evasion, DNA damage, and metastasis [9].

Table 1: Key Virulence Factors of F. nucleatum in Cancer Pathogenesis

| Virulence Factor | Molecular Function | Downstream Effects | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| FadA adhesin | Binds E-cadherin on host cells | Activates β-catenin signaling; promotes proliferation & invasion | CRC cell culture models [7] |

| Fap2 adhesin | Recognizes Gal-GalNAc on cancer cells | Enhances bacterial tropism to tumors; inhibits immune cell cytotoxicity | Binding assays; immune cell cytotoxicity tests [8] |

| Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) | Activates TLR4 signaling | Induces NF-κB activation; pro-inflammatory cytokine production | TLR4 knockout models; cytokine measurements [9] |

| Metabolic byproducts | Alters host cell metabolism | Shifts central carbon metabolism; promotes invasion | Metabolomic profiling; invasion assays [8] |

3Fusobacterium nucleatumin Colorectal Cancer: Clinical Evidence and Diagnostic Applications

Epidemiological Associations and Distribution Patterns

Substantial clinical evidence establishes F. nucleatum's association with colorectal cancer pathogenesis. The abundance of F. nucleatum is generally elevated in feces and cancer tissues from CRC patients, with higher prevalence in right-sided colon cancers (proximal colon > distal colon > rectum) [10]. This distribution may reflect nutritional and environmental preferences of F. nucleatum in the gut [10]. Importantly, F. nucleatum enrichment is already observed in precursor lesions before malignant transformation, including adenomas and serrated polyps, suggesting potential involvement in early carcinogenesis [10].

Longitudinal studies demonstrate that F. nucleatum experience severely abrogates intra-personal stability of microbiome in IBD patients and induces highly variable gut microbiome between subjects [11]. Microbial classifier biomarkers associated with F. nucleatum detection successfully predict microbial alterations in both IBD and non-IBD conditions, providing a novel aspect of microbial homeostasis/dynamics [11].

Diagnostic and Prognostic Performance

F. nucleatum detection shows promising performance as a non-invasive biomarker for CRC screening and prognosis. Cohort studies demonstrate its diagnostic performance with area under the curve (AUC) values of 0.82–0.89 [8]. Importantly, F. nucleatum abundance correlates with advanced disease stage (stage III/IV OR = 2.87), lymph node metastasis (HR = 1.94), and reduced 5-year survival rates (35% vs. 62%) [8]. Metagenomic analysis reveals that high F. nucleatum abundance is closely related to TNM staging (C-index 0.81 vs. 0.69) and recurrence risk (AUC = 0.88) [8]. Notably, a nomogram model integrating F. nucleatum biomarkers improves the predictive accuracy of the traditional TNM staging system by 17.3% [8].

Table 2: Clinical Performance of F. nucleatum as a Biomarker in Colorectal Cancer

| Parameter | Performance Metrics | Study Details | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic Accuracy | AUC 0.82–0.89 | Cohort studies of fecal samples | Non-invasive screening potential |

| Disease Staging | Stage III/IV OR = 2.87 | Meta-analysis of tissue and fecal samples | Identifies advanced disease |

| Lymph Node Metastasis | HR = 1.94 | Tissue-based studies | Predicts aggressive behavior |

| Survival Impact | 5-year survival: 35% vs. 62% (high vs. low Fn) | Longitudinal cohort | Prognostic stratification |

| TNM Staging Enhancement | +17.3% accuracy with nomogram | Model integration studies | Improves current staging systems |

Consistency Across Age Groups

Recent evidence confirms that F. nucleatum associations with CRC remain consistent across different age groups, including young-onset colorectal cancer (yCRC). Deep metagenomic sequencing of stool samples from both old-onset CRC (oCRC) and yCRC patients reveals similar strain-level patterns of F. nucleatum, Bacteroides fragilis, and Escherichia coli [12]. Importantly, CRC-associated virulence factors (fadA, bft) are enriched in both oCRC and yCRC compared to their respective controls [12]. Microbiome-based classification models show similar prediction accuracy for CRC status in old- and young-onset patients, underscoring the consistency of microbial signatures across different age groups [12].

4Fusobacterium nucleatumin Extracolonic Cancers

Beyond colorectal cancer, F. nucleatum has been detected and implicated in the pathogenesis of various other malignancies. Its enrichment in oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) tissues has been demonstrated through multiple studies, though detection rates vary [7]. In OSCC, F. nucleatum exhibits strong adherence to and invasion of human gingival epithelial cells, activating the NF-κB pathway, disrupting epithelial adhesion, and promoting epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [7]. The detection of F. nucleatum correlates with clinicopathological parameters, including tumor size and stage, suggesting potential influence on disease progression [7].

F. nucleatum's role also extends to interactions with human papillomavirus (HPV), particularly in head and neck cancers, suggesting potential synergistic effects in carcinogenesis [7]. Emerging evidence also associates Fusobacterium with pancreatic, esophageal, and gastric cancers, though mechanisms in these malignancies are less characterized [7] [9]. The bacterium's capacity to traverse anatomical boundaries and colonize distant sites underscores its potential systemic impact in cancer development.

Experimental Models and Research Methodologies

Standardized Co-culture Protocols for In Vitro Studies

Transcriptomic analyses of F. nucleatum interactions with CRC cells typically employ standardized co-culture systems. The general protocol involves infection of CRC cell lines (such as HCT116, HT29, or SW480) with F. nucleatum at multiplicities of infection (MOI) ranging from 100:1 to 500:1 (bacteria to eukaryotic cells) under anaerobic conditions [9]. Co-cultures are maintained for varying timepoints (typically 4-24 hours) before RNA extraction and transcriptomic analysis. These studies consistently reveal that F. nucleatum activates multiple chemoresistance-associated pathways, including those driving inflammation, immune evasion, DNA damage, and metastasis [9].

A meta-analysis of public transcriptomic datasets identified consistent patterns across multiple independent co-culture experiments, strengthening the biological relevance of findings [9]. This approach reduces noise and increases confidence in identifying genes consistently altered by F. nucleatum exposure across different experimental conditions.

Metagenomic Sequencing and Analysis Pipelines

For clinical correlation studies, shotgun metagenomic sequencing of stool or tissue samples represents the gold standard for F. nucleatum detection and quantification. The typical workflow includes:

- DNA Extraction: Using standardized kits with mechanical lysis to ensure Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria are equally represented [12]

- Library Preparation: Utilizing Illumina-compatible protocols with appropriate fragment sizes [12]

- Sequencing: Achieving sufficient depth (typically 70 million paired-end reads per sample) to detect low-abundance taxa [12]

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

This methodology allows for comprehensive assessment of F. nucleatum abundance while simultaneously evaluating the broader microbial context and functional potential.

Signaling Pathways and Host-Pathogen Interactions

The following diagram illustrates key molecular pathways through which F. nucleatum promotes colorectal carcinogenesis, based on transcriptomic analyses of infected host cells:

Figure 1: Molecular Pathways of F. nucleatum in Colorectal Cancer

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies for F. nucleatum Research

| Category | Specific Items/Protocols | Application/Purpose | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Strains | F. nucleatum subspecies (animalis, nucleatum, vincentii, polymorphum) | Pathogenesis comparisons | Subspecies show different prevalence in CRC [10] |

| Cell Culture Models | CRC cell lines (HCT116, HT29, SW480); Oral epithelial cells | Host-pathogen interaction studies | Use anaerobic co-culture systems [9] |

| Molecular Reagents | Anti-FadA antibodies; E-cadherin expression constructs; TLR4 inhibitors | Mechanistic pathway validation | Blocking experiments establish causality [7] |

| Animal Models | ApcMin/+ mice; AOM/DSS colitis model; Germ-free mice | In vivo carcinogenesis studies | F. nucleatum alone insufficient for tumorigenesis [10] |

| Omics Technologies | Shotgun metagenomics; RNA-seq; Metabolomics platforms | Comprehensive profiling | Enables strain-level and functional analysis [12] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | MetaPhlAn2; DESeq2; Ingenuity Pathway Analysis | Data analysis and interpretation | Identifies enriched pathways and networks [9] |

The consistent demonstration of Fusobacterium nucleatum as a microbial signature across colorectal cancers and other malignancies underscores its potential significance as a diagnostic biomarker and therapeutic target. Evidence from multiple independent cohorts confirms its association with disease progression, treatment resistance, and poor clinical outcomes. The consistency of these findings across different age groups and geographical populations strengthens the case for its clinical relevance.

However, important challenges remain in translating these findings to clinical practice. Standardized detection protocols, validated threshold values, and defined targeted intervention strategies require further development and validation through multi-center prospective studies [8]. Future research should focus on elucidating the precise mechanisms underlying F. nucleatum's tropism for tumor tissues, its role in the oral-gut axis, and its interactions with other microbial community members in carcinogenesis. Therapeutic approaches targeting F. nucleatum, including antibiotic therapies, phage therapy, and immunomodulatory strategies, represent promising avenues for improving outcomes in F. nucleatum-associated malignancies.

As microbiome research continues to evolve, F. nucleatum serves as a paradigm for understanding how specific microbial constituents can influence cancer biology across traditional organ boundaries. The integration of microbial biomarkers into existing diagnostic and prognostic frameworks holds potential for enhancing precision oncology approaches and ultimately improving patient outcomes.

The human microbiome, a complex ecosystem of bacteria, fungi, and viruses, plays a critical role in maintaining health, and its disruption—termed dysbiosis—is a hallmark of numerous diseases. Advances in high-throughput sequencing and multi-omics technologies are rapidly uncovering specific microbial signatures associated with a spectrum of disorders, from gastrointestinal and respiratory conditions to metabolic diseases. These microbial biomarkers offer immense potential for revolutionizing diagnostic precision, prognostic stratification, and the development of novel therapeutics. This comparison guide objectively evaluates the experimental data and microbial landscapes linked to Crohn's disease, pancreatic cancer, peri-implantitis, and respiratory diseases, framing the findings within the context of biomarker validation for clinical translation. The supporting data, derived from rigorous cohort studies, are synthesized to provide researchers and drug development professionals with a clear overview of the current landscape and methodological standards.

Comparative Analysis of Disease-Associated Microbial Biomarkers

Table 1: Key Microbial Biomarkers and Their Diagnostic Performance Across Diseases

| Disease | Key Associated Microbial Taxa/Signatures | Proposed Functional Mechanisms | Reported Diagnostic Performance (AUC) | Sample Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crohn's Disease (CD) [13] | Panel of 20 species (e.g., Adherent-Invasive E. coli); Depletion of butyrate-producing species | AIEC virulence (adherence, invasion); Depletion of anti-inflammatory SCFAs like butyrate; Disrupted microbial fermentation pathways | 0.94 (External Validation) [13] | Fecal Samples |

| Pancreatic Cancer [14] | Porphyromonas gingivalis, Fusobacterium nucleatum, Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans | Promotion of chronic inflammation; Immune modulation; Production of genotoxic metabolites; Bacterial translocation | DOR*: 4.85 (Single microbiome); 16.33 (Multiple microbiomes) [14] | Saliva / Oral Samples |

| Peri-implantitis [15] | Health: Streptococcus, Rothia; Disease: Prevotella, Porphyromonas, Treponema, Fusobacteria | Shift from aerotolerant Gram-positive to anaerobic Gram-negative bacteria; Increased amino acid metabolism producing pro-inflammatory metabolites | 0.85 (Integrated taxonomic & functional data) [15] | Peri-implant Biofilm |

| Respiratory Diseases (COPD, Asthma) [16] [17] | Gut/Lung Dysbiosis; Increased Proteobacteria (e.g., Haemophilus); Altered SCFA production | Immune dysregulation via gut-lung axis; Altered levels of circulating SCFAs (butyrate, acetate) affecting pulmonary immunity | Data primarily from pre-clinical and association studies [16] [17] | Fecal, BALF, and Lung Tissue |

DOR: Diagnostic Odds Ratio | *BALF: Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid*

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Biomarker Discovery

The identification of robust microbial biomarkers relies on standardized, multi-faceted experimental protocols. The methodologies below are representative of those used in high-quality validation cohort studies.

Sample Collection and Preparation

- Sample Acquisition: Procedures are body-site-specific. For gut microbiome studies, fecal samples are collected and immediately frozen at -80°C to preserve microbial integrity [13]. For oral/oro-pharyngeal microbiomes, saliva or mucosal swabs are used [14]. For respiratory studies, bronchoalveolar lavage (BALF) is collected with protective techniques to avoid upper airway contamination [18]. Peri-implantitis studies use customized protocols to co-isolate biofilm from implant surfaces [15].

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: DNA is extracted for metagenomic and 16S rRNA sequencing using kits designed for complex biological samples (e.g., Qiagen, Mo Bio Powersoil) [15] [13]. For metatranscriptomics, total RNA is extracted, followed by ribosomal RNA (rRNA) depletion to enrich for messenger RNA (mRNA) [13].

- Metabolite Extraction: For metabolomics, fecal samples are homogenized in phosphate buffer, and metabolites are extracted using mechanical disruption with zirconia/silica beads. The supernatant is filtered and prepared for analysis, such as by Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy [13].

Multi-Omics Data Generation and Analysis

- Shotgun Metagenomics: Extracted DNA is sequenced on platforms like Illumina HiSeq. Taxonomic profiling is performed using tools like MetaPhlAn v4, which leverages unique clade-specific marker genes. Functional potential is assessed by mapping reads to databases like UniRef90 using HUMAnN v3 [13].

- Metatranscriptomics: Sequencing libraries are prepared from rRNA-depleted RNA and sequenced. The resulting reads are mapped to custom genomic reference databases to quantify gene expression levels, revealing actively transcribed pathways and virulence factors [15] [13].

- Metabolomics: Processed samples are analyzed via NMR or Mass Spectrometry. Spectral data are referenced against compound libraries (e.g., Chenomx) for metabolite identification and quantification [13].

- Data Integration: Machine learning algorithms (e.g., Canonical Analysis of Principal Coordinates, random forests) are employed to integrate taxonomic, functional, and metabolite data to build predictive models and identify the most robust diagnostic biomarkers [15] [13].

Visualization of Research Workflows and Pathways

Multi-Omics Biomarker Discovery Pipeline

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow from sample collection to biomarker validation, a process common to the cited studies.

The Gut-Lung Axis Immune Pathway

This diagram outlines the key mechanistic pathway by which gut microbiota influence respiratory health, a core concept in understanding diseases like asthma and COPD [16] [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents and Platforms for Microbial Biomarker Research

| Item/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen); Powersoil Pro Kit (Qiagen) | High-quality DNA/RNA isolation from complex samples like stool and biofilm. |

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Ribo-zero Magnetic Kit | Removal of ribosomal RNA to enrich for messenger RNA in metatranscriptomic studies. |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina HiSeq/NovaSeq; PacBio Sequel | High-throughput sequencing for metagenomics and transcriptomics. |

| Bioinformatic Software | KneadData, MetaPhlAn v4, HUMAnN v3, Bowtie2 | Quality control, taxonomic profiling, functional pathway analysis, and read mapping. |

| Reference Databases | UniRef90, Virulence Factor Database (VFDB), NCBI Taxonomy | Functional gene annotation, virulence factor identification, and taxonomic classification. |

| Metabolomics Platforms | Bruker NMR Spectrometer; LC-MS Systems | Untargeted identification and quantification of microbial and host metabolites. |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | R, Python (scikit-learn) | Data integration and building predictive models from multi-omics data. |

The consistent emergence of specific microbial signatures across gastrointestinal, respiratory, and metabolic disorders underscores the microbiome's central role in human pathophysiology. The experimental data synthesized in this guide demonstrate that validated, multi-species biomarker panels can achieve high diagnostic accuracy, as seen in Crohn's disease and peri-implantitis. Furthermore, moving beyond taxonomy to include functional metatranscriptomic and metabolomic data significantly enhances predictive power and provides mechanistic insights.

Future research must focus on standardizing methodologies across larger, multi-center cohorts to facilitate clinical adoption. Longitudinal studies are needed to determine whether microbial shifts are causes or consequences of disease, which is critical for developing targeted microbial therapies like next-generation probiotics or dietary interventions. For drug development professionals, the microbiome presents a novel frontier for therapeutic innovation, offering strategies to modulate these complex ecological landscapes to treat and prevent a wide array of chronic diseases.

The human microbiome represents one of the most promising yet challenging frontiers in modern biomedical research. While numerous studies have identified associations between microbial communities and various disease states, a fundamental question persists: are observed microbiome alterations a cause or consequence of disease? This "chicken-or-egg" dilemma represents the central challenge in translating microbiome research into validated diagnostic tools and targeted therapies [19] [20]. Establishing causality is not merely an academic exercise—it is essential for identifying genuine therapeutic targets, developing reliable biomarkers, and creating effective microbiome-based interventions [21] [22].

The field is currently transitioning from observational studies to mechanistic research that can demonstrate causal relationships. This evolution requires sophisticated experimental frameworks that integrate multi-omics technologies, advanced preclinical models, and rigorous computational approaches [23] [21]. This guide examines the key methodologies, experimental models, and analytical tools enabling researchers to dissect causal relationships in microbiome-disease interactions, with particular emphasis on validation approaches suitable for diagnostic development.

Experimental Frameworks for Establishing Causality

The Sequential Evidence Funnel

Establishing microbiome-disease causality typically follows a systematic investigative progression, often described as an "evidence funnel" that moves from association to mechanism [22]. This framework provides a logical structure for building conclusive evidence and is particularly valuable for designing validation cohort studies.

Table 1: The Five-Level Evidence Funnel for Establishing Microbiome-Disease Causality

| Evidence Level | Experimental Approach | Key Insights Provided | Causal Inference Strength |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1: Association | Microbiome-wide association studies (MWAS) | Identifies microbial taxa/genes correlated with disease states | Weak - identifies correlations only |

| Level 2: Altered Phenotypes | Germ-free animals; antibiotic-treated models | Demonstrates phenotype changes with microbiome depletion | Moderate - shows microbiome involvement |

| Level 3: Phenotype Transfer | Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) | Transfers disease phenotype via microbiome transfer | Strong - demonstrates transferability |

| Level 4: Strain Isolation | Mono-association or defined consortia in gnotobiotic models | Identifies specific strains responsible for phenotypes | Very strong - pinpoints causative strains |

| Level 5: Molecular Mechanism | Metabolomics; genetic manipulation; receptor studies | Identifies specific molecules and mechanisms | Definitive - elucidates molecular pathways |

This funnel approach provides a systematic methodology for progressing from initial observations to mechanistic understanding. Research in obesity and metabolic disorders exemplifies this strategy, where initial observations of altered Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratios in obese individuals (Level 1) progressed through germ-free mouse experiments (Level 2), FMT studies (Level 3), and ultimately to the identification of specific bacterial strains and metabolites like short-chain fatty acids that directly influence host metabolism (Levels 4-5) [19] [22].

Methodological Framework for Causal Inference

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental workflow for establishing causality, from initial correlation to molecular mechanism:

Key Experimental Models & Methodologies

Animal Models for Causal Inference

Animal models remain indispensable for establishing causal relationships in microbiome research, with each model system offering distinct advantages and limitations for different research questions.

Table 2: Animal Models for Establishing Microbiome-Disease Causality

| Model System | Key Features | Best Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Germ-free mice | No native microbiota; allows controlled colonization | Gold standard for FMT studies; mono-association experiments | Altered immune development; costly maintenance |

| Gnotobiotic models | Defined microbial communities | Studying specific microbial interactions; synthetic communities | Limited complexity; may not reflect native microbiota |

| Antibiotic-depleted mice | Microbiome reduction in conventional animals | Rapid assessment of microbiome involvement; adult-stage depletion | Incomplete depletion; off-target drug effects |

| Humanized mice | Human microbiome transplanted into germ-free mice | Studying human-specific microbiome functions | Limited host-microbe co-adaptation; genetic mismatch |

| Zebrafish | Optical transparency; high-throughput screening | Real-time visualization of host-microbe interactions | Physiological differences from mammals |

| Drosophila/C. elegans | Simple microbiota; genetic tractability | High-throughput screening; genetic studies | Limited translational relevance for complex diseases |

| Pigs | Physiological similarity to humans; similar organ size | Nutritional studies; translational research | Cost; limited genetic tools |

The selection of appropriate animal models depends heavily on the research question. For initial phenotype transfer studies, germ-free mice represent the benchmark model, while more complex questions may require humanized models or systems with greater physiological relevance to humans [23] [21]. Recent consensus statements emphasize that no single model is perfect, and combining multiple approaches often provides the most robust evidence for causality [21].

Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Protocols

FMT represents a crucial experimental approach for Level 3 evidence in the causality funnel, enabling researchers to determine whether a disease phenotype can be transferred through microbial communities alone [23] [22]. Standardized protocols are essential for generating reproducible, interpretable results.

Donor-Recipient Protocol Framework:

- Donor Selection & Characterization: Comprehensive screening of donor microbiome (16S rRNA sequencing, metagenomics), health status, and relevant phenotypic traits

- Inoculum Preparation: Fresh or cryopreserved fecal material (typically 80-100 mg/mL in sterile PBS with glycerol cryoprotectant) processed anaerobically

- Recipient Preparation: Germ-free animals preferred; antibiotic-depleted (ampicillin, vancomycin, neomycin, metronidazole for 2-3 weeks) or PEG-treated conventional animals as alternatives

- Transplantation Route & Schedule: Oral gavage (100-200μL) once daily for 3-5 consecutive days to ensure stable engraftment

- Phenotypic Assessment: Monitor disease-relevant parameters at predetermined endpoints (typically 2-8 weeks post-transplantation)

This approach has successfully transferred numerous phenotypes, including obesity, inflammatory bowel disease, and behavioral traits, providing compelling evidence for microbial involvement in these conditions [23] [22]. The consistency of phenotype transfer across multiple independent studies significantly strengthens causal inference.

Advanced Analytical Approaches

Multi-Omics Integration for Mechanistic Insights

The integration of multiple omics technologies is essential for progressing through the causality funnel, particularly for identifying molecular mechanisms (Level 5 evidence). Advanced computational methods now enable researchers to connect microbial features to host responses through systematic bioinformatic pipelines.

Table 3: Multi-Omics Technologies for Microbiome Causal Inference

| Technology | Data Type | Applications in Causality | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shotgun Metagenomics | Microbial genetic potential | Identifying functional capabilities; strain tracking | Does not measure activity; database dependencies |

| Metatranscriptomics | Microbial gene expression | Assessing active microbial functions; regulation studies | Technical variability; host RNA contamination |

| Metabolomics | Microbial metabolite production | Direct measurement of functional output; host-microbe communication | Cannot always trace metabolites to producers |

| Proteomics | Microbial and host protein expression | Direct functional data; host response measurement | Technical complexity; limited dynamic range |

| Metagenome-wide Association Studies (MWAS) | Variant association with phenotype | Linking specific microbial genes to host traits | Population stratification; requires large cohorts |

| Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning | Integrated multi-omics data | Pattern recognition; predictive modeling; biomarker discovery | "Black box" limitations; overfitting risks |

The power of multi-omics integration is exemplified in recent research on myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), where researchers combined gut metagenomics, plasma metabolomics, immune cell profiling, and clinical symptoms using a deep neural network (BioMapAI). This approach achieved 90% accuracy in distinguishing patients from controls and identified specific disruptions in butyrate production and tryptophan metabolism, providing compelling evidence for microbial involvement in this condition [24].

Computational & Statistical Methods for Causal Inference

Several specialized computational approaches have been developed specifically to address causal inference in microbiome research:

Mechanistic Modeling: Ecosystem-level models that incorporate microbial interactions, metabolic networks, and host responses to test causal hypotheses in silico [20].

Mendelian Randomization: Uses genetic variants as instrumental variables to strengthen causal inference in human observational studies, helping to overcome confounding factors [23].

Microbiome Engineering Approaches: CRISPR-based editing of microbial genomes allows direct testing of gene-specific effects on host phenotypes, providing powerful evidence for causal mechanisms [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Platforms

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Causality Studies

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Gnotobiotic isolators | Maintain germ-free or defined microbiota animals | FMT studies; mono-association experiments |

| Cryopreservation media | Preserve microbial communities viability | Banking standardized microbiota inocula |

| Anaerobic chambers | Maintain oxygen-free conditions for strict anaerobes | Culturing fastidious microorganisms |

| 16S rRNA sequencing kits | Characterize microbial community composition | Initial community profiling; diversity assessment |

| Shotgun metagenomics kits | Assess functional genetic potential of communities | Strain-level analysis; gene content assessment |

| Metabolomics platforms | Measure microbial and host metabolites | Functional output assessment; metabolic pathways |

| Organ-on-a-chip systems | Model human organ systems with microbiome | Human-relevant host-microbe interaction studies |

| BioMapAI | Deep neural network for multi-omics integration | Identifying biomarkers across data types [24] |

| ProBiome | Biostatistical framework for microbiome analysis | Standardized analytical pipelines [20] |

| CRISPR-Cas systems | Precise microbial genome editing | Functional validation of microbial genes [25] |

Signaling Pathways in Microbiome-Host Communication

Understanding the molecular mechanisms through which the microbiome influences host physiology requires mapping the specific signaling pathways involved. The following diagram illustrates key established pathways in microbiome-host communication:

Validation Cohort Design & Biomarker Translation

For diagnostic development, rigorous validation cohort design is essential to move from correlative biomarkers to clinically useful tools. Key considerations include:

Prospective Cohort Design: Collecting samples prior to disease development enables true assessment of predictive value rather than mere association.

Multi-center Recruitment: Including diverse populations and geographic locations controls for cohort-specific biases and improves generalizability.

Longitudinal Sampling: Repeated measurements over time help distinguish cause from consequence by establishing temporal relationships.

Integrated Omics Platforms: Combining metagenomics, metabolomics, and host response markers increases predictive power and mechanistic insight, as demonstrated in the ME/CFS research that achieved 90% diagnostic accuracy [24].

Experimental Validation: Correlative findings from human studies should be tested in animal models or in vitro systems to establish causal relationships before diagnostic implementation.

The field is moving toward standardized biomarker validation pipelines that incorporate these elements, with recent consensus statements emphasizing the need for robust methodological standards and interdisciplinary collaboration [21].

Resolving the "chicken-or-egg" dilemma in microbiome-disease relationships requires methodical progression through sequential evidence levels, from initial correlation to molecular mechanism. The experimental frameworks and methodologies outlined in this guide provide a roadmap for researchers seeking to establish causality and develop validated microbiome-based diagnostics and therapies. As the field advances, the integration of multi-omics technologies, sophisticated animal models, and computational approaches will continue to enhance our ability to distinguish causal drivers from secondary consequences, ultimately enabling more targeted and effective microbiome-based interventions.

The human gastrointestinal tract hosts a complex ecosystem of trillions of microorganisms, collectively known as the gut microbiome, which engages in continuous bidirectional communication with distant organs through intricate networks termed "axes" [26]. These include the well-established gut-brain axis [27] [28] and other gut-organ pathways that collectively influence nearly every aspect of human physiology. The vast genetic and metabolic potential of the gut microbiome—encoding approximately 150 times more genes than the human genome—underpins its ubiquity in health maintenance, development, aging, and disease [27]. Emerging research underscores that local microbial dysbiosis (an imbalance in the gut microbial community) does not remain confined to the gastrointestinal tract but exerts systemic effects contributing to the pathophysiology of conditions ranging from neurodegenerative diseases to neurodevelopmental disorders, chronic fatigue, and metabolic conditions [29] [30] [24]. This review synthesizes current evidence on these gut-organ axes, with a specific focus on validating microbiome-derived biomarkers for diagnostic applications and exploring therapeutic implications within precision medicine frameworks.

Key Communication Pathways of the Gut-Organ Axes

The gut microbiome communicates with distant organs through multiple, interdependent signaling pathways. These mechanisms form the foundation for understanding how local dysbiosis can have systemic consequences.

Neural Pathways

The vagus nerve serves as a direct neural highway between the gut and the brain, providing rapid communication that influences mood, appetite, and parasympathetic output [29]. Vagal afferents detect mechanical stretch, nutrients, and microbial molecules in the gut, while efferent fibers carry brain commands back to influence gastrointestinal activity [29]. The significance of this pathway is highlighted by research showing that individuals who underwent vagotomy (surgical cutting of the vagus nerve) have a lower subsequent risk of developing Parkinson's disease, suggesting this pathway may facilitate the transmission of disease-provoking agents [29] [28]. Beyond the vagus nerve, the enteric nervous system (ENS)—sometimes called the "second brain"—contains over 100 million neurons that regulate gut motility, secretion, and blood flow [29] [28]. This extensive neural network can operate independently but maintains constant communication with the central nervous system.

Immune and Inflammatory Pathways

Gut microbes profoundly shape host immunity from development through adulthood [31] [29]. The gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) represents the body's largest immune compartment, continuously sampling microbial antigens and coordinating appropriate responses [29]. Specific microbial groups drive the differentiation of distinct immune cell populations; for instance, segmented filamentous bacteria promote pro-inflammatory Th17 cells, while Clostridium species foster anti-inflammatory regulatory T cells (Tregs) [31]. Microbial-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs), such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Gram-negative bacteria, can breach a compromised intestinal barrier, enter circulation, and trigger systemic inflammation, including neuroinflammation, by activating Toll-like receptors (TLRs) in peripheral tissues and the brain [29] [26]. This immune-mediated communication creates a vicious cycle wherein brain disorders are not confined to the CNS but involve a systemic network including the gut ecosystem [29].

Endocrine and Metabolic Pathways

Gut microbes produce and modulate a vast array of neuroactive and systemically active molecules. Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs)—including acetate, propionate, and butyrate—are produced by microbial fermentation of dietary fiber and serve as crucial regulators of innate and adaptive immunity [31] [29]. SCFAs interact with G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) and act as histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors to modulate inflammatory responses and influence T-cell differentiation [31]. Additionally, gut microbiota produce or influence the production of various neurotransmitters, including serotonin (5-HT), dopamine, and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) [32] [27]. Notably, approximately 90% of the body's serotonin is produced in the gut, where it influences motility and also communicates with the brain via the vagus nerve [32] [28]. Other crucial metabolites include bile acid derivatives and tryptophan metabolites, which can cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and influence CNS function [32] [29].

Figure 1: Key Communication Pathways of the Gut-Organ Axes. The gut microbiome communicates with distant organs through neural, immune, metabolic, and endocrine pathways, transmitting specific microbial signals that influence systemic physiology [31] [29] [27].

Disease-Specific Microbial Dysbiosis and Systemic Implications

Local alterations in gut microbial composition have been consistently associated with a spectrum of diseases across organ systems. The tables below summarize key dysbiosis signatures and their systemic implications across different disease categories.

Table 1: Microbial Dysbiosis Signatures in Neurological and Neuropsychiatric Conditions

| Disease/Condition | Consistent Microbial Alterations | Key Associated Metabolite Changes | Proposed Systemic Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parkinson's Disease (PD) | Increase: Lactobacillus, Akkermansia, Bifidobacterium; Decrease: Lachnospiraceae, Faecalibacterium [32] | Reduced SCFAs; Altered bile acid metabolism [29] | Vagus nerve transmission of α-synuclein pathology; neuroinflammation via microglial activation; intestinal barrier dysfunction [29] [28] |

| Alzheimer's Disease (AD) | Distinct profiles vs. healthy controls; Specific taxa implicated in preclinical AD [29] [27] | Altered SCFA patterns; Inflammatory microbial metabolites [29] | Compromised blood-brain barrier; microglial dysfunction (impaired Aβ clearance); systemic inflammation promoting neuroinflammation [27] |

| Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) | Lower microbial diversity; Depletion of beneficial taxa [30] | Altered SCFA profiles; disrupted tryptophan metabolism [30] | Immune activation; increased intestinal permeability ("leaky gut"); neuroimmune signaling; production of neuroactive metabolites [30] |

| Major Depressive Disorder | Gut-brain module analysis reveals distinct neuroactive potential [33] | Serotonin pathway disruption; inflammatory mediators [32] [24] | Vagal pathway modulation; HPA axis dysregulation; systemic inflammation affecting mood centers [26] |

| Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/ Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) | Microbial imbalance with elevated tryptophan, benzoate [24] | Lower butyrate; nutrient deficiencies; heightened inflammatory responses [24] | Disrupted microbiome-metabolite-immune interactions linked to fatigue, pain, sleep, and emotional symptoms [24] |

Table 2: Microbial Dysbiosis Signatures in Non-Neurological Conditions

| Disease/Condition | Consistent Microbial Alterations | Key Associated Metabolite Changes | Proposed Systemic Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) | Alterations in underreported species: Asaccharobacter celatus, Gemmiger formicilis, Erysipelatoclostridium ramosum [34] | Significant metabolite shifts: amino acids, TCA-cycle intermediates, acylcarnitines [34] | Perturbed microbial pathways and functions tied to inflammation; compromised mucosal immune homeostasis [31] [34] |

| Type 2 Diabetes (T2D) | Distinct enterotypes associated with disease progression [34] | 111 gut microbiota-derived metabolites significantly associated with T2D, particularly in BCAA, aromatic AA, and lipid pathways [34] | Microbial regulation of glucose homeostasis; insulin resistance through inflammatory mediators; energy harvest modulation [34] |

| Colorectal Cancer (CRC) | Elevated Bacteroides fragilis and other CRC-associated taxa [34] | Oncometabolites; decreased protective SCFAs [34] | Chronic inflammation; direct microbial genotoxicity; modulation of cellular proliferation/apoptosis [34] |

| Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) | Specific dysbiosis signatures identified [32] | Altered bile acid metabolism; increased inflammatory mediators [32] | Bacterial translocation; endotoxin-induced inflammation; metabolic endotoxemia driving hepatic steatosis [32] |

Diagnostic Validation: From Microbiome Biomarkers to Clinical Applications

The translation of microbiome science into clinical practice relies on robust biomarker discovery and validation. Metagenomic sequencing has emerged as a cornerstone for precision diagnostics, enabling culture-independent pathogen detection and microbiome-based disease stratification [34].

Metagenomic Approaches and Analytical Frameworks

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing allows comprehensive profiling of microbial communities with unprecedented resolution [34]. The analytical workflow typically involves sample collection (often stool), DNA extraction, library preparation, high-throughput sequencing, bioinformatic processing (quality control, taxonomic profiling, functional annotation), and statistical integration with clinical metadata [34]. Key considerations for validation studies include:

- Standardization: Implementing standardized protocols (e.g., STORMS checklist) and reference materials (e.g., NIST stool reference) to reduce technical variability [34].

- Multi-omics Integration: Combining metagenomics with metabolomics, proteomics, and immunoprofilng to capture functional interactions [34] [24].

- Longitudinal Design: Tracking microbiome dynamics over time to establish temporal relationships and causal inference [30] [34].

- Machine Learning: Applying computational models to identify predictive microbial signatures and build diagnostic classifiers [34] [24].

Figure 2: Diagnostic Validation Workflow for Microbiome Biomarkers. The pathway from sample collection to validated biomarker panel involves multiple analytical stages, with integration of multi-omics data and clinical metadata to ensure robust biomarker performance [34] [24].

Clinically Validated Biomarker Performance

Several microbiome-based diagnostic models have demonstrated promising performance in clinical validation studies:

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): Diagnostic models built on integrated microbiome-metabolome signatures achieved high accuracy (AUROC 0.92-0.98) in distinguishing IBD from controls across 13 cohorts [34].

- Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS): The BioMapAI platform, integrating gut metagenomics, plasma metabolomics, immune cell profiles, and clinical symptoms, achieved 90% accuracy in distinguishing individuals with ME/CFS from healthy controls [24].

- Colorectal Cancer (CRC): A novel machine learning framework integrating metagenomic data with clinical parameters demonstrated superior accuracy in predicting CRC risk compared to existing methods [34].

- Type 2 Diabetes (T2D): Diagnostic panels generated from gut microbiota-derived metabolites achieved AUROC exceeding 0.80 for predicting disease progression [34].

These validation studies highlight the translational potential of microbiome-based diagnostics while underscoring the importance of multi-center cohorts, diverse population representation, and rigorous analytical standards [34].

Experimental Models and Methodologies for Gut-Organ Axis Research

Key Experimental Protocols

Research into gut-organ axes employs complementary experimental approaches spanning reductionist models to human studies:

Germ-Free (GF) Animal Models

- Protocol: Animals raised in sterile isolators with no exposure to microorganisms; can be colonized with specific microbial communities at defined timepoints [31] [30].

- Applications: Establishing causal roles of microbiota in neurodevelopment, immune function, and behavior; GF mice exhibit significant immune deficiencies, altered stress responses, and neurochemical abnormalities [31] [26] [30].

- Limitations: Artificial conditions; developmental compensation; limited translational relevance to complex human ecosystems [30].

Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT)

- Protocol: Transfer of processed stool material from donor to recipient; in humans typically via colonoscopy, capsules, or enema; in animals via oral gavage [29] [34].

- Applications: Demonstrating transmissibility of phenotypes; therapeutic modification of recipient microbiome; studying microbial engraftment dynamics [29] [34].

- Validation: Metagenomic monitoring of donor strain engraftment; functional assessment through metabolomic profiling [34].

Gnotobiotic Models

- Protocol: Colonization of GF animals with defined microbial communities (human-derived microbiotas or simplified synthetic communities) [31].

- Applications: Determining functional contributions of specific microbial taxa or communities; studying community assembly and stability [31].

- Advantages: Combines experimental control of GF systems with physiological relevance of microbial colonization [31].

Multi-Omics Integration in Human Cohorts

- Protocol: Simultaneous collection of metagenomic, metabolomic, immunologic, and clinical data from well-phenotyped cohorts; integrated computational analysis [34] [24].

- Applications: Identifying biomarker signatures; mapping interactions across biological domains; generating hypotheses about mechanisms [24].

- Validation: Cross-validation in independent cohorts; testing in experimental models [34] [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Gut-Organ Axis Studies

| Reagent/Platform | Function/Application | Specific Examples/Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing | Comprehensive taxonomic and functional profiling of microbial communities | Illumina platforms; Oxford Nanopore for real-time sequencing [34] |

| 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing | High-throughput taxonomic profiling of bacterial communities | Cost-effective for large cohort studies; limited functional information [34] |

| Metabolomics Platforms | Characterization of small molecule metabolites derived from host and microbiome | LC-MS for SCFAs, bile acids, neurotransmitters; GC-MS for volatile compounds [34] [24] |

| Gnotobiotic Isolators | Maintenance of germ-free animals for colonization studies | Flexible film or rigid isolators; strict sterility monitoring protocols [31] |

| Organ-on-a-Chip Models | Microphysiological systems mimicking human gut-brain axis | Gut-brain axis chips with fluidic channels connecting intestinal and neural compartments [32] |

| Bioinformatic Pipelines | Processing and analysis of microbiome sequencing data | QIIME 2, mothur, HUMAnN for functional profiling; custom scripts for integration [34] |

| Artificial Intelligence Platforms | Integrated multi-omics analysis and biomarker discovery | BioMapAI for deep neural network modeling of microbiome-immune-metabolite interactions [24] |

Therapeutic Implications and Microbiome-Targeted Interventions

The gut-organ axis presents promising targets for therapeutic intervention across multiple disease states. Current approaches focus on modifying the gut microbiome or its metabolic output to restore homeostasis.

Microbiota-Targeted Therapeutic Strategies

Probiotics and Prebiotics

- Probiotics: Live microorganisms that confer health benefits when administered in adequate amounts [33]. Specific strains like Bifidobacterium longum APC1472 have shown anti-obesity effects in human trials [33].

- Prebiotics: Substrates selectively utilized by host microorganisms conferring health benefits [33]. Beyond traditional prebiotics (inulin, FOS), the concept is expanding to include human milk oligosaccharides, resistant starch, and polyphenols [33].

- Clinical Evidence: Multi-strain probiotics and specific strains (Bifidobacterium lactis, Bacillus coagulans Unique IS2) show effectiveness for chronic constipation; probiotics demonstrate benefits in some neurological, metabolic, and liver diseases [32] [33].

Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT)

- Mechanism: Entire community approach to restore healthy microbial ecosystem [29] [34].

- Applications: Effective for recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection; under investigation for IBD, ASD with GI symptoms, and IBS [34].

- Optimization: Success depends on stable donor strain engraftment and restoration of key metabolites (SCFAs, bile acid derivatives, tryptophan metabolites); donor-recipient age compatibility may influence outcomes [34].

Dietary Interventions

- High-Fiber Diets: Increase SCFA production; high-fiber diet boosted SCFA production, expanded Tregs, strengthened gut barrier, and reduced CNS inflammation in EAE model of MS [29] [28].

- Fermented Foods: Increase microbial diversity and reduce inflammatory markers [28].

- Personalized Nutrition: Accounting for individual microbial variability in response to dietary components [33].

Small Molecule Therapies

- Postbiotics: Preparations of inanimate microorganisms and/or their components that confer health benefits [33].

- Receptor Agonists/Antagonists: Targeting specific microbial metabolite receptors (e.g., GPCR agonists for SCFAs) [31] [32].

- Microbial Metabolite Supplementation: Direct administration of beneficial microbial metabolites [29].

Clinical Translation Challenges

Despite promising preclinical results, clinical translation of microbiota-targeted therapies faces several challenges:

- Inter-individual Variability: Individual microbiome composition influenced by genetics, diet, lifestyle, and environment complicates universal interventions [32] [30].

- Causality Establishment: Determining whether microbiota alterations are cause, consequence, or modifier of disease processes [29] [30].

- Standardization: Lack of standardized protocols for microbiome-based therapies and outcome measures [34].

- Long-term Safety: Particularly important for pediatric interventions and FMT [30] [34].

The gut-organ axes represent fundamental communication networks that integrate local microbial communities with systemic physiology and disease processes. Mounting evidence demonstrates that microbial dysbiosis contributes to pathogenesis across multiple organ systems through immune, neural, endocrine, and metabolic pathways. While significant progress has been made in characterizing these interactions, several challenges remain for translating this knowledge into clinical practice.

Future research directions should prioritize:

- Longitudinal Multi-omics Studies: Tracking microbiome development and dynamics alongside host physiology over time in diverse populations [30] [34].

- Mechanistic Validation: Moving beyond correlations to establish causal relationships using gnotobiotic models, bacterial cultivation, and targeted interventions [31] [34].

- Standardization and Reproducibility: Implementing harmonized protocols, reference materials, and analytical frameworks across research centers [34].

- Personalized Approaches: Developing microbiome-informed precision medicine strategies accounting for individual microbial, genetic, and environmental contexts [32] [34].

- Ethical and Regulatory Frameworks: Addressing emerging ethical considerations in microbiome-based therapies and diagnostics [30] [34].

As these scientific and translational challenges are addressed, targeting the gut-organ axes holds immense promise for developing novel diagnostic, preventive, and therapeutic strategies across a spectrum of human diseases. The integration of microbiome science into clinical practice represents a paradigm shift toward more holistic, systems-level approaches to human health and disease.

Advanced Methodologies for Microbial Biomarker Discovery and Validation

The study of complex microbial ecosystems has evolved dramatically with the advent of high-throughput sequencing technologies. While metagenomics reveals the genetic potential of a microbial community and metatranscriptomics captures its actively expressed functions, metabolomics identifies the resulting biochemical byproducts [35]. Individually, each approach provides valuable but limited insights: metagenomics answers "what microorganisms are present and what could they potentially do?", metatranscriptomics addresses "what functions are they actively performing?", and metabolomics completes the picture by revealing "what metabolites are being produced?" [35]. However, integrative multi-omics approaches provide a powerful framework for understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying host-microbiome interactions in both health and disease states, offering unprecedented insights for diagnostic biomarker discovery and therapeutic target identification [36] [13] [34].

The clinical relevance of multi-omics integration is particularly evident in microbiome research, where microbial dysbiosis has been implicated in numerous conditions including inflammatory bowel disease, metabolic disorders, and various cancer types [13] [34]. By combining these complementary datasets, researchers can move beyond correlative associations toward mechanistic understandings of how microbial communities influence host physiology and disease pathogenesis [13]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these three omics technologies, their experimental protocols, and their integrated application in microbiome biomarker research.

Technology Comparison: Complementary Methodological Approaches

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, outputs, and applications of the three omics technologies in microbiome research.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of metagenomics, metatranscriptomics, and metabolomics technologies

| Aspect | Metagenomics | Metatranscriptomics | Metabolomics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical Target | Microbial DNA [36] [37] | Total RNA/mRNA [36] [37] | Small molecule metabolites [35] |

| Primary Output | Taxonomic profile & functional potential [36] [35] | Gene expression patterns & active pathways [36] [37] | Metabolic fluxes & end products [35] |

| Key Strengths | Identifies community composition; detects unculturable organisms [36] [37] | Reveals actively expressed genes; dynamic response view [36] [37] | Direct reflection of functional state; high sensitivity [35] [13] |

| Main Limitations | Functional inference only; host DNA contamination [36] [34] | RNA instability; host RNA contamination; computational complexity [36] [37] | Difficult metabolite identification; complex data interpretation [35] |

| Common Platforms | 16S rRNA sequencing; Whole Metagenome Shotgun [36] [35] | RNA-Seq [36] [13] | NMR; LC-MS; FTIR [13] [38] |

| Diagnostic Utility | Microbial signature identification [13] [34] | Active pathway analysis [13] [15] | Metabolic biomarker detection [13] [34] |

Key Differentiating Factors

The temporal resolution represents a fundamental distinction between these approaches. Metagenomics provides a static snapshot of microbial composition and genetic potential, while metatranscriptomics and metabolomics offer dynamic insights into microbial activities and outputs at the time of sampling [37]. This temporal dimension enables researchers to capture microbial community responses to environmental changes, therapeutic interventions, or disease progression.

From a clinical translation perspective, these technologies also differ in their biomarker potential. Metagenomic signatures can stratify patients based on their microbial composition, as demonstrated by enterotyping approaches [34]. Metatranscriptomics identifies actively expressed virulence factors and metabolic pathways with direct pathological significance [13] [15]. Metabolomics detects microbial metabolites with systemic effects on host physiology, such as short-chain fatty acids, bile acids, and amino acid derivatives [13] [34].

Experimental Protocols: From Sample to Data

Metagenomics Workflow

Metagenomic analysis begins with sample collection (stool, tissue, or other specimens) followed by DNA extraction using kits designed for microbial lysis [13]. For 16S rRNA sequencing, PCR amplification targets hypervariable regions of the bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA gene, followed by sequencing on platforms such as Illumina [36] [35]. Whole Metagenome Shotgun (WMS) sequencing fragments all DNA in the sample without targeted amplification, providing greater genomic coverage but requiring deeper sequencing [36]. Bioinformatic processing involves quality control (e.g., using KneadData), taxonomic profiling with tools like MetaPhlAn, and functional annotation using databases such as UniRef90 [13].

Metatranscriptomics Workflow

Metatranscriptomic analysis requires careful RNA preservation at collection due to RNA instability [36] [37]. After total RNA extraction, mRNA enrichment is performed through ribosomal RNA depletion [13]. The extracted mRNA is then reverse transcribed to complementary DNA (cDNA) and prepared for high-throughput sequencing [36]. Bioinformatic analysis includes read mapping to reference genomes, transcript quantification, and differential expression analysis [13] [15]. A significant challenge is distinguishing microbial RNA from abundant host RNA, particularly in low-biomass samples [36].

Metabolomics Workflow

Metabolomic analysis typically begins with metabolite extraction using appropriate solvents based on the chemical properties of target metabolites [13]. For NMR-based approaches, samples are mixed with a deuterated solvent and a reference compound (e.g., TSP) [13]. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) provides higher sensitivity for detecting low-abundance metabolites, while Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy offers a rapid, cost-effective alternative suitable for large-scale studies [38]. Data processing involves spectral alignment, peak detection, metabolite identification using reference libraries, and multivariate statistical analysis [13].

Integrated Multi-Omics Workflow

The integrated workflow combines these methodologies to provide a comprehensive view of microbial community structure and function. The following diagram illustrates the sequential relationship between these analytical approaches:

Figure 1: Integrated multi-omics workflow for microbiome analysis

Applications in Diagnostic Biomarker Research

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) Mechanisms

A landmark multi-omics study investigating Crohn's disease (CD) employed shotgun metagenomics on 212 samples, metatranscriptomics on 103 samples, and metabolomics on 105 samples [13]. The metagenomic analysis identified a panel of 20 microbial species that achieved exceptional diagnostic performance with an area under the ROC curve (AUC) of 0.94 in distinguishing CD from healthy controls [13]. Metatranscriptomics revealed significant alterations in microbial fermentation pathways, explaining the depletion of anti-inflammatory butyrate observed in metabolomic profiles [13]. Integration of all three datasets uncovered novel mechanisms where adherent-invasive Escherichia coli (AIEC) utilized propionate to drive expression of the ompA virulence gene, critical for bacterial adherence and invasion of host macrophages [13].

Peri-Implantitis Diagnostics

Research on peri-implantitis integrated full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing with metatranscriptomics in 48 biofilm samples from 32 patients [15]. This approach revealed a shift from health-associated Streptococcus and Rothia species in healthy implants to anaerobic Gram-negative bacteria in diseased states [15]. Metatranscriptomic analysis identified enzymatic activities and metabolic pathways associated with disease, particularly highlighting the importance of amino acid metabolism in pathogen survival and virulence [15]. The integration of taxonomic and functional data enhanced predictive accuracy to an AUC of 0.85, outperforming single-omics approaches [15].

Urinary Tract Infection Pathogenesis

A study of urinary tract infections (UTIs) applied metatranscriptomic sequencing with genome-scale metabolic modeling to characterize active metabolic functions in patient-specific urinary microbiomes [39]. This approach revealed marked inter-patient variability in microbial composition, transcriptional activity, and metabolic behavior [39]. Analysis of virulence factor expression identified distinct strategies for nutrient acquisition and host invasion among uropathogenic E. coli strains [39]. The integration of gene expression data with metabolic models narrowed flux variability and enhanced biological relevance, highlighting the potential for personalized treatment approaches for managing multidrug-resistant infections [39].

Table 2: Key findings from multi-omics studies in human diseases

| Disease Context | Metagenomic Findings | Metatranscriptomic Findings | Metabolomic Findings | Diagnostic Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|